Abstract

Introduction: Menopause is one of the most important crises in the life of women. The control of menopause symptoms is a main challenge in providing care to this population. So, the aim of present study was to investigate the effect of education through support group on early symptoms of menopause. Methods: In this randomized controlled clinical trial 124 postmenopausal women who had a health records in Valiasr participatory health center of Eslamshahr city were participated. These women were allocated by block randomization method into support group (62 women) and control group (62 women).Women in support group was assigned into 6 groups. Three 60-minutes educational sessions were conducted in 3 sequential weekly sessions. Early menopausal symptoms were measured before and 4 weeks after the intervention by using Greene scale (score ranged from 0 to 63). Data analysis was performed by ANCOVA statistical test. Results: There were no statistical differences between two groups in demographic characteristics and the total score of the Greene scale before intervention. The mean score of the Greene scale in support group was statistically less than control group 4 weeks after intervention. The number of hot flashes in the support group was significantly lower than control group, 4 weeks after intervention.Conclusion: Education through support group was effective in reducing the early symptoms of menopause. Thus, this educational method can be used as an appropriate strategy for enhancing women’ health and their dealing with annoying symptoms of menopause.

Keywords: Education, Support group, Menopause

Introduction

Menopause is an important phase in the life of all women that occurs following the permanent cessation of menstruation due to lack of ovarian follicular activity after 12 months.1 The mean age of menopause is 51 years, but it isn’t the same in different parts of the world. For example, this mean is 51.2 years in Italy2 and 48.2 years in Iran.3 The result of a study by Rajaeefard et al., showed that the mean age of menopause among Iranian women is lower than global average and averages reported from developed countries.3 In addition, according to national population census nearly 5 million elderly women (between 45 to 59 years) are living in Iran. Furthermore, with an increase in life expectancy,4 women spent almost a third of their life in the postmenopausal period.5,6Thus, problems associated with this period of women’ life need more attention.5

Menopause is associated with reduced ovarian activity that is characterized by decreased hormonal level and its complications such as hot flashes, sleep disturbance, urinary urgency, bladder inflammation, and readiness for urinary infection.6One of the most common symptom of menopause is related to vasomotor system7with a reported prevalence between 18 and 85 percent in different studies. This percent is about 75% among American women over 50 years8 and about 53.1% among Iranian women.9Hot flash is a feeling of intense heat in the chest, head, and neck that often associated with night sweat.10This symptom may alter the sense of well-being and create negative impacts on work performance, physical activity, enjoyment of life, and overall quality of life amongst postmenopausal women.11In result, empowerment of women in coping with menopause require community-based interventions.12The first and most important step in this regard is obtaining basic information about the menopausal transition process and this goal is achievable via promoting health education.13

Health education is an acquisitive subject and reinforced through learning.14Health education is an approach with a particular plan that can be conducted by considering demographic characteristics of participants.

This approach facilitates optimum use of time and resources via selection of appropriate educational methods and proper use of educational aids.14

In a study by Satoh and Ohashi from the viewpoint of Japanese menopausal women was investigated about application of different educational methods. The results showed that 83% of women wanted information about menopause symptom sand ways to deal with these symptoms through different educational methods. Also, there was no significant association between the severity of menopausal symptoms and reduced quality of life.15

The support group is a systematic and deliberate conversation about a particular topic that is interest for all participants.

This educational method recognized as one of interactive learning methods. Support group initiated with an introductory lecture and then participants collaborate and interact with each other on the topic of interest.16This method is one way of indirect teaching and can be designed and implemented in diverse populations based on their needs. Support group may be used largely based on social and cultural context.14

In a study by Rotem et al., on the effects of education via support group in improving attitude and coping with physical and psychosocial aspects of menopause were investigated. This study reported a significant improvement in these symptoms, while did not investigate the impact of this method on sexual symptoms.17

The result of another study by Yazdkhasti et al., showed that individualized teaching method and support group decrease the vasomotor, psychosocial, physical, and sexual symptoms among Iranian postmenopausal women equally.18

Rostami et al., reported that educational program that consisted of lecturing and questioning and designed for 4 weeks (one session in each week) improve the life of menopausal women in sexual, physical, and psychosocial domains. But, this method showed no meaningful effect on vasomotor domain.19

Previous studies have revealed that postmenopausal women often suffer from a lack of information. As a result, examining their perceptions regarding menopausal problem sand ways of dealing with these problems is valuable.20-22

In this regard, the effectiveness of educational programs based on lecturing and questioning8and individualized education via support group18was investigated on quality of life among Iranian postmenopausal women. The support group is associated with an active involvement of participants. So, this educational method is a preferred method for many participants. In addition, there are no studies investigated the effectiveness of a support group on early symptoms of menopause, especially by using Greene scale.

Additionally, according to the Statistical Center of Iran, 31% of the Iranian population is in the age group between 15 and 29 years and they will be in the middle age group in the next 20 to 30 years. Therefore, careful planning is necessary to ensure the health of this population. So, the aim of present study was to investigate the effect of education through support group on early symptoms of menopause (primary outcome) and number of hot flashes (secondary outcome). The hypothesis of this study was the education can improve early symptoms of menopause.

Materials and Methods

This study was a randomized controlled clinical trial that conducted on postmenopausal women aged from 45 to 59 years. These women had a health records in Valiasr participatory health center of Eslamshahr city. According to a study by Yausi et al.,23and based on some indicators (α = 0.05, =β 0.1, m1= 17.2, m2= 14.6, SD1= 3.8, SD2= 3.8) the sample size of each group was calculated as 56 women. Considering the possible 10% loss of sample the number of women in each group increased to 62 women.

Inclusion criteria for participants were including: educated at least in guidance school; be married; non-smoking cigarette or hookah; not drinking alcohol; not taking estrogen or phytoestrogen-containing herbal medicines over the past three months; not using drugs for hot flash such as clonidine and gabapentin; flushing at least twice a day; absence of any severe stressors such as death of close relatives during the last three months. Exclusion criteria were including: use of any sexual hormone replacement until the end of the study; unwillingness to continue participation in the study at any stage; any physical or mental illness or surgical intervention during the intervention; not participating in training sessions.

The data collection tool was included demographic checklist, Greene scale, and hot flash checklist. The demographic checklist was included questions about age, menopausal age, education, job, parity, sufficiency of monthly income, number of rooms in the home, number of family members, life satisfaction, type of residency, previous training about menopause, and current level of physical activity.

Greene scale was originally developed in 1975 by Greene in Scotland and its reliability and validity have been approved in previous studies.24The scale independently measures psychological, physical, vasomotor, and sexual symptoms of menopause and include 21 items. The answer to each item is variable from 0 to 3. Score 0 is for the absence of symptom; score 1 is for the presence of low level of symptom; score 2 is for the presence of moderate level of symptom; score 3is for the presence of severe level of symptom.

Items 1 to 11 measures psychological symptoms; which is divided into two anxiety and depression subscales. (Items 1 to 6 are for anxiety and items 7 to 11 are for depression). Items 12 to 18 are for physical symptoms of menopause, items 19 and 20 are for vasomotor symptoms, and item 21 is for sexual dysfunction.25The average score of Greene scale ranges from 0 to 63 that is calculated by adding up the scores for all items. Frequency of hot flashes during 24 hours was recorded by women daily using a checklist. The validity of Greene scale was determined using content validity and the reliability was examined by using thetest-retest method after pilot study of 30 women.

The reliability of the scale was confirmed by internal consistency coefficient (0.88 to 0.97), ICC= 0.94, and Cronbach's alpha coefficient (0.85).

For data collection, the list of all postmenopausal women aged from 45 to 59 years was extracted from Valiasr participatory health center of Eslamshahr city. Then, the selected women were invited to attend in the briefing session with a phone call made by the main researcher. In a briefing session, the pretest tool (including demographic checklist, Greene scale, and hot flash checklist) was filed out by all women after explaining the aims and methods of the study. Then, signed informed consent was taken from all women. Then participants were allocated into intervention and control groups randomly using block randomization method, by using units of 4 and 6 blocks, and an allocation ratio of 1: 1.

The support group program was conducted in three continuous 60-minute weekly sessions in the morning. This program held in a workshop with circle arrangement of the chairs in order to increase the interaction of participants with each other. Due to the extraordinary number of participants in the support group this program was conducted in 4 groups with 10 participants and 2 groups with 11 participants. All participants informed that they should refer for sessions on determined schedule and if they cannot attend any session they should inform the researcher via a telephone call. For these women another meeting was coordinated. In cases that any participant does not contribute in meetings, the reason was investigated and alternative program was organized for another day.

At the beginning of each session, the researcher explained the topics covered in that session for 15 minutes. Then participants were asked to discuss about their experience about selected topic in 30 minutes. In the remaining 15 minutes, the researchers made a conclusion form the discussions.

Topics specified for each session were including: (a) Session one was about definition of menopause and its importance; physical symptoms and practical interventions to deal with them. (b) Session two was about vasomotor symptoms and decreased libido and practical interventions to managing them. (c) Session three was about psychological symptoms and practical interventions to managing them. No intervention was done for control group. To obey the research ethic rules, an instruction was given to all women in control group after finishing the intervention. This instruction was contain information about menopause and practical ways to deal with menopause symptoms.

Data was analyzed using SPSS statistical software ver 13. The normality of data was confirmed by using Kolmogorov-Smirnov statistical test. The distributions of all demographic variables, total Greene score and all its dimensions and the frequency of hot flashes were normal. For comparison the scores of normal variables before the intervention among two groups independent samples t-test was used. In addition, ANCOVA statistical test, with control the effect of pre-intervention score, was used for comparison these scores after 4 weeks of finishing intervention.

This project approved by Regional Ethics Committee at Tabriz University of Medical Sciences (code number = 9217).

Results

In this study, 62 menopausal women aged from 45 to 59 years were participated in each group. Two women in support group were excluded due to unwillingness to participate in intervention sessions and two ones in control group were excluded due to hysterectomy and hormone therapy. So, the number of participants in each group was reduced to 60 women (Diagram 1).

Diagram 1 .

Flow chart of the study

There were no statistical differences between two groups before intervention in age, age at menopause, parity, job, life satisfaction, crowding index (ratio between the number of family members and number of rooms in the home), previous education about menopause, and physical activity (P> 0.05) (Table 1). There were statistically significant differences in educational level and Body Mass Index (BMI) of two groups before intervention (P< 0.05) (Table 1).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of menopausal women in control and intervention groups. (n= 60) .

| Demographic characteristics | Support group | Control group | Statistical indicators |

| Age (year) | 52.0 (4.0) | 52.8 (4.2) | 0.640§ |

| Menopausal age (year) | 46.8 (4.1) | 48.1 (4.0) | 0.763§ |

| Educational level | <0.001†† | ||

| Lower than diploma | 52 (63.4) | 30 (36.6) | |

| Higher than diploma | 8 (21.1) | 30 (78.9) | |

| Number of children | 0.345†† | ||

| Lower than 2 | 12 (41.4) | 17 (58.6) | |

| 2 - 5 | 41 (47.1) | 46 (52.9) | |

| 5 and higher | 2 (50.0) | 2 (50.0) | |

| Job | 0.066‡ | ||

| Housewife | 54 (53.5) | 47 (46.5) | |

| Employed | 6 (31.6) | 13 (68.4) | |

| BMI (kg/m303)† | 0.117§ | ||

| 18.5-24.99 | 5 (22.7) | 17 (77.3) | 0.003†† |

| 25-29.99 | 21 (51.2) | 20 (48.8) | |

| ≥ 30 | 21 (38.2) | 34 (61.8) | |

| Life satisfaction | 0.890‡ | ||

| Completely satisfied | 20 (48.8) | 21 (51.2) | |

| Satisfied to some what | 33 (52.4) | 30 (47.6) | |

| dissatisfied | 7 (43.8) | 9 (56.2) | |

| Crowding index | 0.405‡ | ||

| Less than two people per-room | 44 (48.4) | 47 (51.6) | |

| 2-3 people per-room | 11 (52.4) | 10 (47.6) | |

| More than 3 people per-room | 4 (66.7) | 2 (33.3) | |

| Education about menopause | 12 (48.0) | 13 (52.0) | 0.500‡ |

| Physical activity * | 41 (52.6) | 37 (47.4) | 0.283‡ |

§independent samples t-test, ††exact chi-square, ‡ chi-square;† in BMI no participants obtained score less than 18.5; *physical activity means doing simple exercises or walking 30 minutes daily

The mean age of women in both groups was approximately 52 years. About half of participants were educated less than diploma level. Almost half of women had 2 to 5 previous deliveries and about half of them were housewife. About half of women were “somewhat” satisfied with their life and almost half of them had received training about menopause. About half of women had acceptable levels of physical activity before the intervention (Table 1).

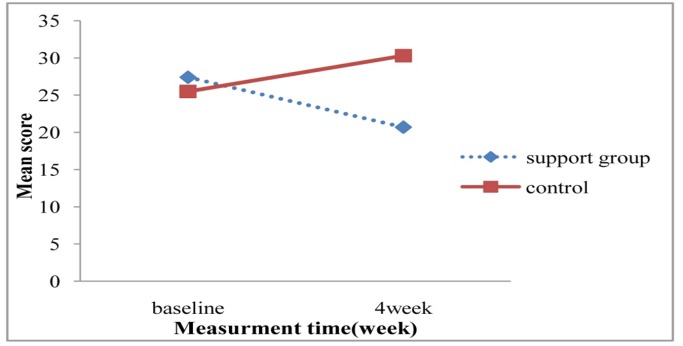

There were no statistical differences between two groups in total Greene score and the scores of its subscales before starting intervention (P> 0.05). On the other hand, the mean of total Greene score in support group was statistically less than control group 4 weeks after intervention. Similarly, support group showed noticeable improvement in all subscales of Greene scale (psychological, physical, vasomotor, and sexual) in comparison with control group 4 weeks after intervention (P< 0.001) (Table 2).

Table 2. Comparison the outcomes in postmenopausal women in support group and control group. (n= 60).

| Support group | Control group | Comparison support group and control group | ||

| Symptoms | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | MD(95% CI) * | p |

| Greene scale (0-63) | ||||

| Before intervention | 27.4 (12.6) | 25.5 (12.7) | 1.8 (-2.7, 6.4) | 0.640 |

| 4 weeks after intervention | 20.7 (8.6) | 30.3 (12.1) | -11.06 (-12.5, -9.6) | < 0.001 |

| Vasomotor symptoms (0-6) | ||||

| Before intervention | 3.2 (1.8) | 2.6 (1.8) | 0.6 (0.005, 1.3) | 0.770 |

| 4 weeks after intervention | 2.3 (1.2) | 3.2 (1.7) | -1.3 (-1.5, -1.03) | < 0.001 |

| Psychological symptom (anxiety, 0-13.) | ||||

| Before intervention | 8.2 (4.4) | 7.7 (4.9) | 0.4 (-1.2, 2.1) | 0.414 |

| 4 weeks after intervention | 5.9 (3.0) | 8.7 (4.9) | -3.1 (-3.6, -2.6) | < 0.001 |

| Psychological symptom (depression, 0-18.) | ||||

| Before intervention | 7.06 (3.9) | 6.2 (3.7) | 0.8 (-0.5, 2.2) | 0.386 |

| 4 weeks after intervention | 5.2 (2.8) | 7.6 (3.5) | -3.04 (-3.5, -2.4) | < 0.001 |

| Physical symptoms (0-21) | ||||

| Before intervention | 7.5 (4.3) | 7.2 (4.8) | 0.2 (-1.4, 1.9) | 0.735 |

| 4 weeks after intervention | 6.1 (2.9) | 8.9 (4.3) | -2.9 (-3.5, -2.3) | < 0.001 |

| Sexual symptoms (0-3) | ||||

| Before intervention | 1.3 (1. 1) | 1.7 (1.3) | -0.3 (-0.8 , 0.07) | 0.070 |

| 4 weeks after in tervention |

0.01 (0.9) | 1.8 (1.2) | -0.5 (-0.6 , -0.3) | < 0.001 |

| Frequency of hot flashes | ||||

| Before intervention | 32.2 (20.1) | 20.6 (11.4) | 11.5 (5.6, 17.4) | < 0.001 |

| 4 weeks after intervention | 24.8 (14.5) | 22.4 (12.4) | - 5.6 (-8.3, -2.9) | < 0.001 |

The score of pretest was compared between two groups by independent samples t-test and after intervention by ANCONA with control of pretest score;*Mean difference(95% Confidence interval of the difference)

The mean score for psychological symptoms (anxiety and depression respectively) were significantly lower in the support group compared to control group 4 weeks after intervention.

The mean score for vasomotor symptoms was significantly lower in the support group compared to control group 4 weeks after intervention.

The mean score for physical symptoms was significantly lower in the support group compared to control group 4 weeks after intervention. The mean score for sexual dysfunction was significantly lower in support group compared to control group 4 weeks after intervention.

The number of hot flashes was significantly higher in support group compared to control group 4 weeks after intervention (Table 2).

The green scale score were decreased in support group 4 weeks after intervention, whereas these symptoms were increased in control group (diagram 2).

Diagram 2.

Greene scale score in control and support group in different times of measurement

Discussion

This study is the first investigated the effect of education via support group on early symptoms of menopause. Moreover, the frequency of hot flashes before and after intervention were investigated and compared. This study showed that support group is able to reduce the early symptoms of menopause. This efficacy was evident in reducing the mean scores of Greene score and all its dimensions and also in the frequency of hot flashes in the support group comparing with control group.

No previous study has examined the effect of individualized teaching method and support group on early symptoms of menopause in Iran or other parts of the world. It should be noted that the symptoms and complications of menopause have a direct association with quality of life. In addition, menopausal quality of life questionnaire and Greene scale14,15are very similar to each other. In results, in this section the results of some studies that investigated the effect of training on quality of life are presented.

In the study of Forouhari et al.,8 the impact of education was investigated on the quality of life of meanapusal women in Shiraz. The result showed that quality of life score reduced in intervention group (that means improvement in quality of life) and this impact were clearly visible on physical, psychosocial, vasomotor, and sexual domains, while control group showed a slight increase in the score of quality of life.

Although, the number of educational sessions in this study was lower than the study of Forouhari et al.,8 but the effect of education on menopausal symptoms after the intervention were clearly visible in this study.

In addition, in the study of Forouhari8 the quality of life score was assessed in two groups three months after the intervention.

The result of this study is comparable with the result of a study by Yazdkhasti et al.,14that investigated the effect of education through support groups on improving the quality of life in 110 postmenopausal women in RobatKarim city in Iran. This study showed a positive impact of this intervention on the physical, psychosocial, vasomotor, and sexual domains of quality of life.

In another study, Rotem et al.,17 examined the effect of education via support group on quality of life of menopausal women and reported that this method has a positive impact on physical, psychological, and social dimensions of quality of life; while the impact on the vasomotor dimension was not measured.

In a study by Hebert et al.,26 the impact of support group on mental and physical health of caregivers of patients diagnosed with Alzheimer were investigated. The intervention lasted for 8 weeks, but had a slight effect on increasing the awareness of family members of patients and was not effective on other variables such as behavioral indicators.

Herbert et al., reported that low sample size (15 caregivers), low power of test 0.60, and the size effect of 0.8 were the main reasons for this result. People with Alzheimer disease have different symptoms over the years. In result, their need for receiving support from their caregivers can change during disease trajectory.

Rostami et al., in a quasi-experimental study investigated the effect of direct education on quality of life of postmenopausal women.

Result showed a positive impact of lecturing on sexual, physical, and psychosocial dimensions, while this method did not have a significant effect on the vasomotor dimension.19It should be noted that this study had no control group and the effect of education was evaluated only in the intervention group.

The result of present study showed that the early symptoms of menopause were decreased in support group 4 weeks after intervention, whereas these symptoms were increased in control group that may be due to the progressive nature of menopause. This result is comparable with the result of one study by Arian27which investigated the effect of education on quality of life in postmenopausal women in Tehran. Results showed that education improved the quality of life in intervention group, while the quality of life in control group decreased due to progressive nature of menopause.

It is likely that relaxation technique and exercises inserted in the guide book do not respected by women in support group. Also, the probability of this problem was reduced by accurate assessment of participants and telephone follow up of women. In most societies the problems of women in reproductive age are more important than problems of menopausal women. Also, the number of postmenopausal women is increasing and there are few studies on appropriate culture-based educational programs in the field of menopause in Iran.

So, other studies are recommended to help Iranian women on dealing with menopausal symptoms especially with low cost and available educational methods such as pamphlet.

Conclusion

The result of present study showed that education via support group reduced the annoying symptoms of menopause. It should be noted that women spend a third of their life in postmenopausal period. Thus, issues associated with this period of life are of particular importance. So, application of support group as a suitable educational method for enhance women’ health and increase their coping with menopause symptoms is recommended.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to all women who participated in the study and the health personnel in Valiasr participatory health center of Eslamshahr city.

Ethical issues

None to be declared.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest in this study.

References

- 1.Greendale GA, Lee NP, Arriola ER. The menopause. Lancet. 1999;353 (9152):571–80. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)05352-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parazzini F. Determinants of age at menopause in women attending menopause clinics in Italy. Maturitas . 2007; 56 (3):280–87. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rajaeefard A, Mohammad-Beigi A, Mohammad-Salehi N. Estimation of natural age of menopause in Iranian women: a meta-analysis study. Koomesh . 2011;13 (1):1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 4.World health statistics. [cited Feb. 2014]. Switzerland: WHO; 2014. Available from: http://www.who. int/gho/ publications/ world_ health_statistics/2014/en/.

- 5.Davari S, Dolatian M, Maracy MR, Sharifirad G. The effect of a health belief model ( HBM)- based educational program on the nutritional behavior of menopausal women in Isfahan. Iran J Med Educ . 2009; 10(5):1263–72. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fritz MA, Speroff L. Clinical gynecologic endocrinology and infertility. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Lippinicott Williams and Wilkins; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moilanen J, Aalto AM, Hemminki E, Aro AR, Raitanen J, Luoto R. Prevalence of menopause symptoms and their association with lifestyle among Finnish middle-aged women. Maturitas . 2010;67(4):368–74. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Forouhari S, Safari Rad M, Moattari M, Mohit M, Ghaem H. The effect of education on quality of life in menopausal women referring to Shiraz Motahhari clinic in 2004. Journal of Birjand University of Medical Sciences. 2009;16(1):39–45. (Persian) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ashrafi M, Kazemi Ashtiani S, Malekzadeh F, Amirchaghmaghi E, Kashfi F. Symptoms of natural menopause among Iranian women living in Tehran, Iran. Iran J Reprod Med . 2010; 8 (1):29–32. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berek JS. Berek and Novak's Gyneconolgy. 14th ed. philadelphia: Lippinicott Williams and Wilkins; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carpenter JS. The hot flash related daily interference scale: a tool for assessing the impact of hot hlashes on quality of life following breast cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage . 2001; 22 (6):979–89. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(01)00353-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.What is the evidence on effectiveness of empowerment to improve health? Copenhagen: WHO; 2006. Available from: http:// www. euro. who. int/ Document/ E88086. pdf.

- 13.Hunter M, O'Dea I. An evaluation of a health education intervention for mid-aged women: five year follow-up of effects upon knowledge, impact of menopause and health. Patient Educ Couns . 1999; 38 (3):249–55. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(98)00143-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yazdkhasti M, Keshavarz M, Merghati KE, Hoseini AF. The effect of structured educational program by support group on menopause women’s quality of life. Iranian Journal of Medical Education. 2012;8 (11):986–94. (Persian) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Satoh T, Ohashi K. Qualityoflife assessment in community-dwelling, middle-aged, healthy women in Japan. Climacteric . 2005; 8 (2):146–53. doi: 10.1080/13697130500117961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rothert ML, Holmes-Rovner M, Rovner D, Kroll J, Breer L, Talarczyk G, Schmitt N, Padonu G, Wills C. An educational intervention as decision support for menopausal women. Res Nurs Health . 1997; 20 (5):377–87. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-240x(199710)20:5<377::aid-nur2>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rotem M, Kushnir T, Levine R, Ehrenfeld M. A psycho-educational program for improving women’s attitudes and coping with menopause symptoms. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs . 2005; 34 (2):233–40. doi: 10.1177/0884217504274417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yazdkhasti M, Keshavarz M, Merghati KE, Hoseini AF. Two learning models substantialy of self directed learning and support group on quality of life in menopausal women [master's thesis]. Tehran: Tehran University of Medical Sciences; 2011. (Persian). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rostami A, Ghofrani Pour F, Ramezanzadeh F. The effect of education on quality of life in women [master's thesis]. Tehran: Tarbiat Modares University; 2001. (Persian). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ayers B, Forshaw M, Hunter MS. The impact of attitudes towards the menopause on women's symptom experience: a systematic review. Maturitas . 2010; 65 (1):28–36. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2009.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hasanpour Azghadi B, Abbasi Z. Effect of education on middle-aged women’s knowledge and attitude towards menopause in Mashhad. Journal of Birjand University of Medical Sciences. 2006;13 (2):9–15. (Persian) [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karimi M. Evaluation of the effect of educational intervention based on empowerment model of health promotion behaviors on menopausal women. Medical Daneshvar 2011; 18 (94): 73-80. (Persian). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yausi T, Yamada M, Uemura H, Ueno S, Numata S, Ohmori T. et al. Changes in circulating cytokine levels in midlife women with psychological symptoms with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor and Japanese traditional medicine. Maturitas . 2009; 62 (2):146–52. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2008.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Daley A, Stokes-Lampard H, MacArthur C. Exercise for vasomotor menopausal symptoms. Cochrane Database of SystematicReviews. 2011;5(1):3–18. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006108.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barentsen R, van de Weijer, van Gend S, Foekema H. Climacteric symptoms in a representative Dutch population sample as measured with the greene climacteric scale. Maturitas . 2001; 38 (2):123–8. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(00)00212-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hebert R, Leclerc G, Bravo G, Girouard D, Lefrancois R. Efficacy of a support group programme for care-givers of demented patients in the community: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Gerontol Geriatr . 1994; 18 (1):1–14. doi: 10.1016/0167-4943(94)90043-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arian S. The effect of educational program on menopausal women [master's thesis]. Tehran: Tarbiat Modares University; 2001.