Abstract

Inconsistent information about drug-drug interactions can cause variations in prescribing, and possibly increase the incidence of morbidity and mortality. The aim of this study was to assess whether there is an inconsistency in drug-drug interaction listing and ranking in three authoritative, freely accessible online drug information sources: The British National Formulary; The Compendium about Drugs Licensed for Use in the United Kingdom (the Electronic Medicines Compendium) and the Compendium about Drugs Licensed for Use in the United States (the DailyMed). Information on drug-drug interactions for thirty drugs which have a high or medium potential for interactions have been selected for analysis. In total, 1971 drug-drug interactions were listed in all three drug information sources, of these 992 were ranked as the interactions with the potential of clinical significance. Comparative analysis identified that 63.98% of interactions were listed in only one drug information source, and 66.63% of interactions were ranked in only one drug information source. Only 15.12% listed and 11.19% ranked interactions were identified in all three information sources. Intraclass correlation coefficient indicated a weak correlation among the three drug information sources in listing (0.366), as well as in ranking drug interactions (0.467). This study showed inconsistency of information on drug-drug interaction for the selected drugs in three authoritative, freely accessible online drug information sources. The application of a uniform methodology in assessment of information, and then the presentation of information in a standardized format is required to prevent and adequately manage drug-drug interactions.

KEY WORDS: drug information, drug-drug interactions, clinical significance, compendium, summary of product characteristics

INTRODUCTION

Drug-drug interactions are the important cause of therapeutic problems and increased number of hospital admissions within the European Union [1]. The study which investigated the causes of hospital admissions of 18820 patients in the United Kingdom (UK) showed that drug-drug interactions were responsible for about 17% of hospital admissions because adverse drug effects [2]. The withdrawal half of drugs from the market in the United States (US), because of safety reasons, during the period 1999-2003, was associated with important drug interactions [3]. The adverse effects of drugs which is a consequence of drug interactions, can be prevented by taking appropriate action. It was estimated that more than three-quarters of clinically significant drug interactions can be avoided [4]. For adequate management of drug-drug interactions, the access to relevant information sources is very important for health professionals [5]. There are numerous compendia with information on the drug interactions. However, compendia often do not document methodology for listing as well as ranking the potential clinical severity of drug-drug interactions. This may be reason for inconsistent informing. Inconsistent drug-drug interaction information can cause variations and confusions in prescribing, possibly increasing the incidence of morbidity and mortality [6]. As an example, according to the British National Formulary (the BNF) and the Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC) of amiodarone licensed for use in the UK coadministration of amiodarone and beta-blockers should be avoided, but can be safely administered under close monitoring according to other authoritative sources [7, 8]. Stockley’s Drug Interactions even reports that coadministration may be therapeutically beneficial. Additionally, previous studies have shown that there is inconsistencyin drug-drug interaction information [5, 9-15]. Studies were included standard drug compendia such as the BNF, the Vidal, the Micromedex® (Drug-Reax) program, the Drug Interactions Facts, the US Pharmacopeia Drug Information, the American Hospital Formulary Service Drug Information (AHFS), Stockley’s Drug Interactions, Hansten’s Drug Interactions Analysis and Management, German Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPCs), in printed or electronical form. When it comes to information sources which doctors and pharmacists use to identify potential drug-drug interaction, the results of previous studies have shown that electronic references have been consulted most often (MicroMedex, Internet, PDA, UpToDate) 51% and 79%, subsequently. Printed information sources (AHFS, Facts & Comparasions) have been used by 9% of doctors and 24% of pharmacists [16]. Health professionals often do not have specialized interaction textbooks to hand or support drug-drug interactions screening programs [17]. Therefore, the aim of this study is to identify whether there is consistency in listing as well as ranking clinical significance of drug-drug interaction in three authoritative, freely accessible online drug information sources.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Criterion for the selection of information sources for analysis

Three analysed compendia were the BNF [18]; the Compendium about Drugs Licensed for use in the UK (the electronic Medicines Compendia (eMC)) [19] and the Compendium about Drugs Licensed for Use in the USA (the DailyMed) [7]. The BNF is a publication of the Medical Society of the United Kingdom and the Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain, it is independent, reliable and practice-oriented source of information which is widely used by clinicians around the world [20]. The eMC and the DailyMed contain information about drugs in the form of SmPC. The SmPC represents the legal basis of information for health professionals on how to use the medical product safely and effectively [21, 22]. These three selected compendia are characterized by the unlimited access to information by the Internet.

Criteria for selection of drugs for analysis and comparison of information

Drugs selected for analisys have a high potential for interactions (for example fluconazole) or belong to major therapeutic classes of drugs which are most frequently involved in drug interactions (for example hydrochlorothiazide) (Table 1) [18, 23]. No more than one drug of a given therapeutic class (third level according to Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System) was included in analysis because many drug interactions may be common to members of the same class. SmPC for oral route of administration was randomly chosen in conditions where the drug was licensed for use under different brand names. In the BNF the section “Appendix – Drug Interactions” was consulted, in the other two compendia the section “Interactions with other medical product and other forms of interaction” was always evaluated first and in case of cross-references, information included in the sections “Dosage and method of administration”, “Contraindications” and “Special warnings and precautions for use” were also taken into account. All drug-drug interactions for 30 selected drugs were identified in all three compendia. Comparison of drug-drug interaction information was made on the basis of two criteria:

TABLE 1.

Drugs selected for analysis

Whether drug-drug interaction was listed in the selected source of information at all.

Are there clear recommendations for management of drug-drug interaction (for example, adjustment of dosing regimen), that is, whether the drug-drug interaction was considered clinically significant.

The BNF uses bolding to mark clinically significant interactions, which are assessed as potentially risky. Thus, it is recommended that drug co-administration is avoided or carefully monitored. In the other two compendia, clinically significant interactions were considered those where according to SmPC there are contraindications for a combined administration of the drugs, or SmPC suggests avoiding the combined administration of the drugs or using drug with modification therapeutic regimen and/or closer monitoring of the patient because of clinical significance of drug-drug interaction. Additionally, if a case that SmPC did not comment on the significance of interactions, we considered as clinically significant pharmacodynamic (PD) interactions which may have a significant risk for the patient and require intervention [4, 24] and pharmacokinetic (PK) interactions which increase and decrease PK parameters (area under the curve, elimination half-life or total clearance), at least 100% and 50%, respectively and for the compounds with a narrow therapeutic window at least 50% and 33%, respectively [5].

Statistical analysis

The consistency in listing and in ranking of clinically significant drug interactions among three compendia was estimated using descriptive statistics and calculating intraclass coefficient of correlation (ICC) [25].

RESULTS

Listed drug-drug interactions

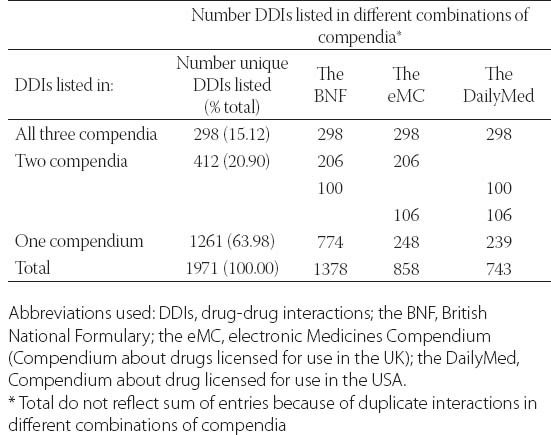

Overall, 1971 interactions were listed for 30 analyzed drugs in all three compendia (range 8-179 per drug). The most comprehensive source of information is the BNF with 1378 listed drug-drug interactions which is almost twice as more than in the DailyMed (Table 2). Table 2 also shows how interactions were listed in each individual compendium reflecting their consistency. Thus, the majority of drug-drug interactions 1261 (63.98%) were listed in only one compendium (Table 2), while was in all three compendia 298 (15.12%) drug interactions were listed. The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) with calculated value of 0.366 indicates a weak correlation among the three compendia in listed drug-drug interactions (values < 0.7 indicate a weak correlation) [25].

TABLE 2.

Consistency among three compendia in listing of drug-drug interactions

Ranked drug-drug interactions

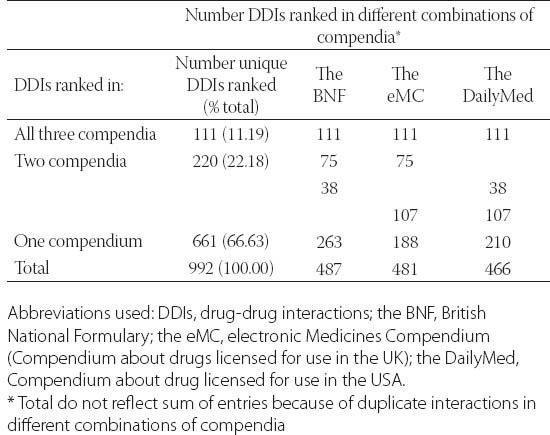

Overall, 992 interactions were ranked as clinically significant in all three compendia (range 0-153 per drugs). The number of interactions per compendium is in the range from 466 in the DailyMed to 487 in the BNF (Table 3). The proportion of ranked interactions in relation to the total number of listed drug-drug interactions is the greatest in the DailyMed – 62.84%. Table 3 also shows how interactions were ranked in each individual compendium reflecting their consistency. Most of the ranked drug-drug interactions 661 (66.63%), were identified in only one compendium, while in all three compendia only 111 (11.19%) ranked drug-drug interactions were identified. ICC was 0.467, slightly higher than ICC for the listed drug interactions, although the value also indicated a weak correlation among the three compendia [25].

TABLE 3.

Consistency among three compendia in ranking of drug-drug interactions

DISCUSSION

The results of this research have shown inconsistency in listing and ranking drug-drug interactions among three compendia. Sixty four percentage of interactions were listed in one drug information source, and 66.63% of interactions were ranked in one drug information source. In all three compendia the percentage of listed and ranked drug interactions was only 15.12% and 11.19%, respectively. Inconsistency in providing information on drug interactions across compendia could be explained by several factors. Firstly, analyzed compendia do not list information sources which were used to assess drug-drug interactions. Therefore, there is a possibility of considering different and limited available drug information sources such as unpublished research by pharmaceutical companies, spontaneous drug interaction reports collected through national post-marketing surveillance systems or published studies about drug-drug interactions in the other languages than English. Secondly, there is inconsistent and inaccurate classification of drugs. For example, according to the US SmPC, the co-administration of digoxin and calcium channel blockers may lead to blocking atrio-ventricular (AV) of conduction, while according to the UK SmPC there are reports for digoxin and each calcium channel blockers individually (diltiazem, nifedipine, nisoldipin, amlodipine, felodipine, isradipin, lercandipin, nicardipine, nimodipine, nitrendipine and verapamil), with noticed differences in the clinical significance of interactions. Or, according to the UK SmPC, we should avoid concurrent use of methotrexate and potentially hepatotoxic drugs. The information in the US SmPC are more precise, for example azathioprine, sulfasalazine and retinoides were defined as hepatotoxic drugs. The results of our study are in concordance with the results of other similar studies. Previous studies analyzed different drug information sources and used different approaches in the evaluation of interaction information and also showed inconsistency in informing about drug-drug interactions. Thus, Fulda’s et al study showed inconsistency in listing and ranking clinical significance of interactions in five US compendia (the US Pharmacopeia Drug Information, the American Hospital Formulary Service Drug Information, Hansten’s Drug Interactions Analysis and Management, the Drug Interaction Facts (Facts and Comparisons) and the Micromedex® program) for five therapeutic class of drugs (angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, benzodiazepines, beta blockers, calcium channel blockers and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)) [10]. Comparative analysis showed that between 58.0% and 64.4% of interactions were listed in only one of the compendia, while between 1.0% and 3.1% of interactions were listed in all five compendia, depending on analyzed therapeutic class. When it comes to ranking the clinical significance of the interaction, there were not any ranked interactions which were identified in all five compendia for four therapeutic classes (benzodiazepines, beta blockers, calcium channel blockers, NSAIDs), whereas in the class of ACE inhibitors, 66.7% of ranked interactions were identified in all five compendia. Bergk et al. [5] compared information about clinically significant interactions (listing, class labeling, description of effects, recommendations for management) in the German SmPC and three standard drug interactions sources, the DRUGDEX, Hansten/Horn’s Drug Interactions Analysis and Management and Stockley’s Drug Interactions. The results showed that information was equivalent for only 33.0% (192/579) of analyzed interactions, 16.0% of interactions were not identified in German SmPC and 51% of information was not sufficiently informative. The Vitry’s study analyzed 50 drugs which have a high potential for interactions or belong to major therapeutic classes of drugs which are most frequently involved in drug interactions. Only 6.33% of major drug interactions were listed in all four analyzed international compendia, i.e. the BNF, the Vidal (French drug compendium) and two US compendia, the Drug Interaction Facts and the Micromedex® program while between 14% and 44% interactions which were classified as major were listed in only one of the compendia [9]. Reggi et al compared the consistency of information on indications, dosage in adult population, side effects and precautions for ciprofloxacin, fluoxetin and nifedipine in the BNF, the UK SmPC and the US SmPC. Their results showed high consistency of information in the BNF (as a golden standard) and information in the UK SmPC for all three analyzed drugs, and high consistency of information in the BNF and information in the US SmPC for two analyzed drugs (degree of information agreement was ≥ 3 for grouped all varibles) [20]. In contrast, according to results of our study, these compendia were not consistent for information referring to drug-drug interactions. It means if we observe three information sources (the BNF, the UK SmPC and the US SmPC), the consistency of drug information depends on the observed variables. Thus, information for variables indications, dosing in adult population, side effects and precautions are consistent, while information for drug-drug interactions are not consistent. Therefore, findings suggest that there is only need to improve information agreement among the BNF, the UK SmPC and the US SmPC for variable drug-drug interactions. However, using different approaches in evaluation of drug information in Reggi’s et al and our study requires further researches for final conclusion. There are several limitations for this study. Firstly, we did not analyze all the interactions of all drugs. Also, drugs which belong to the same therapeutic class were not selected for analysis. However, previously published studies indicate that it is unlikely that the selection of drugs for the analysis contributed to the inconsistency of information on drug-drug interactions [10, 14, 15]. Secondly, the selection of the SmPC for analysis may affect research results. International comparative study showed that drug information contained in the SmPCs different brand names of a same compound can be different even within one country [20]. Finally, information in compendia in which there were not clear recommendations for the management of interactions may result in a different interpretation of clinical significance of the interaction. For example, prolonged regular use of paracetamol may enhance anticoagulant effects of warfarin and other coumarins [18, 19]. Or, co-administration of hydrochlorthiazide and iodine-based contrast agents in high doses may result in increased risk of acute renal failure [19]. Terms prolonged regular use of paracetamol and use of iodine-based contrast agents in high doses are not precisely defined. To achieve uniformity in ranking a clinical significance of interactions, Hansten et al. [26] besides quality of evidence and severity of side-effects, were proposed and additional criteria for classification of drug-drug interactions, those were consistency of the reported effect with the known interactive properties of two drugs, frequency in using two drugs in general patient population and its relationship with the number of reported cases of adverse drug interaction, and medicolegal consideration (i.e. if there are warnings in drug labeling). Also, Partnership to prevent drug-drug interactions developed sixteen criteria to define a list of clinically important drug-drug interactions in community and ambulatory pharmacy settings. Criteria (i.e. questions) were grouped in four sections: evidence supporting the interaction, severity of the interaction, probability of the interaction, and probability of coadministration of the interacting drugs. The answer to every question was ranged from 1 to 10, and finally, 25 clinically important drug-drug interactions were identified by consensus process [27]. However, these initiatives to improve classification of drug interactions have not contributed to consistency in listing and ranking drug interactions in information sources.

CONCLUSION

The study has shown the inconsistency of information on drug interactions in three authoritative, freely accessible online compendia in listing and in ranking of clinical significance of drug-drug interactions. The inconsistency enhances for both study criteria with increasing number of drug information sources. The results are more significant because analyzed drugs belong to the class of drugs with high or frequent potential for clinically significant interactions. Since these analyzed compendia do not document methodology in listing as well as in ranking of the potential for clinical significance interactions, the application of a uniform methodology in assessment of information based on the best evidence, and then the presentation of information in a standardized format is required to prevent and adequate management of adverse effects which are the consequence of drug-drug interactions.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to professor Slobodan M Janković, Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Kragujevac, Serbia, for his critical comments.

DECLARATION OF INTEREST

No sources of funding were used to assist in the preparation of this study. The authors have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this study.

REFERENCES

- [1].London: European Medicines Agency, Committee for Human Medicinal Products; [accessed: 10 March 2012]. Guideline on the Investigation of Drug Interactions, Draft 2010 [Internet] Available from: http://www.aaps.org/insidefocus_groups/DrugTrans/imagespdfs/EMEADDIguidance.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- [2].Pirmohamed M, James S, Meakin S, Green C, Scott AK, Walley TJ, et al. Adverse drug reactions as cause of admission to hospital: prospective analysis of 18820 patients. BMJ. 2004;329(7456):15–19. doi: 10.1136/bmj.329.7456.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Huang SM, Lesko LJ. Drug-drug, drug-dietary supplement, and drug-citrus fruit and other food interactions: what have we learned? J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;44(6):559–569. doi: 10.1177/0091270004265367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].van Roon EN, Flikweert S, le Comte M, Langendijk PN, Kwee-Zuiderwijk WJ, Smits P, et al. Clinical relevance of drug-drug interactions: a structured assessment procedure. Drug Saf. 2005;28(12):1131–1139. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200528120-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Bergk V, Haefeli WE, Gasse C, Brenner H, Martin-Facklam M. Information deficits in the summary of products characteristics preclude an optimal management of drug interactions: a comparasion with evidence from the literature. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;61(56):327–335. doi: 10.1007/s00228-005-0943-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Valuck RJ, Byrns PJ, Fulda TR, Vander Zanden J, Parker S. Methodology for assessing drug-drug interaction evidence in the peer-reviewed medical literature. Curr Ther Res Clin Exp. 2000;61(8):553–568. [Google Scholar]

- [7].DailyMed [Internet]. Bethesda: U.S. National Library of Medicine. [accessed: 14 March 2012]. Available from: http://dailymednlm.nih.gov/dailymed .

- [8].Baxter K. London: Pharmaceutical Press; 2010. Stockley's Drug Interactions Pocket Companion 2010. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Vitry AI. Comparative assessment of four drug interaction compendia. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;63(6):709–714. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2006.02809.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Fulda TR, Valuck RJ, Vander Zanden J, Parker S, Byrns PJ. The US Pharmacopeia Drug Utilization Review Advisory Panel. Disagreement among drug compendia on inclusion and ratings of drug-drug interactions. Curr Ther Res Clin Exp. 2000;61(8):540–548. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Abarca J, Malone DC, Armstrong EP, Grizzle AJ, Hansten PD, Van Bergen RC, et al. Concordance of severity ratings provided in four drug interaction compendia. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003) 2004;44(2):136–141. doi: 10.1331/154434504773062582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Vonbach P, Dubied A, Krähenbühl S, Beer JH. Evaluation of frequently used drug interaction screening programs. Pharm World Sci. 2008;30(4):367–374. doi: 10.1007/s11096-008-9191-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Wang LM, Wong M, Lightwood JM, Cheng CM. Black box warning contraindicated comedications: concordance among three major drug interaction screening programs. Ann Pharmacother. 2010;44(1):28–34. doi: 10.1345/aph.1M475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Chao SD, Maibach HI. Lack of drug interaction conformity in commonly used drug compendia for selected at-risk dermatologic drugs. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6(2):105–111. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200506020-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Trifirò G, Corrao S, Alacqua M, Moretti S, Tari M, Caputi AP, et al. Interaction risk with proton pump inhibitors in general practice: significant disagreement between different drug-related information sources. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;62(5):582–590. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2006.02687.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Ko Y, Abarca J, Malone DC, Dare DC, Geraets D, Houranieh A, et al. Practioners’ views on computerized drug-drug interaction alerts in the VA system. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2007;14(1):56–64. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M2224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Aronson JK. Drug interaction - information, education, and the British National Formulary. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;57(4):371–372. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2004.02125.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Joint Formulary Committee. London: Pharmaceutical Press; 2011. [accessed:10 March 2012]. British National Formulary 62 [Internet] Available from: http://bnf.org/bnf/index.htm . [Google Scholar]

- [19].Leatherhead: Datapharm Communications Limited; [accessed: 14 March 2012]. The Electronic Medicines Compendium [Internet] Available from: http://www.medicines.org.uk/emc . [Google Scholar]

- [20].Reggi V, Balocco-Mattavelli R, Bonati M, Breton I, Figueras A, Jam-bert E, et al. Prescribing information in 26 countries: a comparative study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;59(4):263–270. doi: 10.1007/s00228-003-0607-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Bergk V, Gasse C, Schnell R, Haefeli WE. Requirements for a successful implementation of drug interaction information system in general practice: Results of a questionnaire survey in Germany. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;60(8):595–602. doi: 10.1007/s00228-004-0812-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Almelo: European Commission, Consumer Goods - Pharmaceuticals; [accessed: 10 March 2012]. A Guideline on Summary of Product Characteristics, Notice to Applicants 2009 [Internet] Available from: http://ec.europa.eu/health/files/eudralex/vol-2/c/smpc_guideline_rev2_en.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- [23].Lee A, Stockley IH. Interakcije lijekova. In: Walker R, Edwards C, editors. Klinicka farmacija i terapija. Zagreb: Školska knjiga; 2004. pp. 23–32. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Tatro D, editor. St. Louis MO: Wolters Kluwer; 2011. Drug Interaction Facts 2012: The Authority on Drug Interactions. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Futrell D, editor. When quality is a matter of taste, use reliability indexes. Qual Prog. 1995;28(5):81–86. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Hansten PD, Horn JR, Hazlet TK. ORCA: OpeRational ClassificAtion of drug interactions. J Am Pharm Assoc (Wash) 2001;41(2):161–165. doi: 10.1016/s1086-5802(16)31244-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Malone DC, Abarca J, Hansten PD, Grizzle AJ, Armstrong EP, Van Bergen RC, et al. Identification of serious drug-drug interactions: results of the partnership to prevent drug-drug interactions. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003) 2004;44(2):142–151. doi: 10.1331/154434504773062591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]