Abstract

Background: A gelatin sponge with slowly releasing basic fibroblast growth factor (b-FGF) enhances chondrogenesis. This study investigated the optimal amount of b-FGF in gelatin sponges to fabricate engineered cartilage.

Materials and Methods: b-FGF (0, 10, 100, 500, 1000, and 2000 μg/cm3)-impregnated gelatin sponges incorporating β-tricalcium phosphate (β-TCP) were produced. Chondrocytes were isolated from the auricular cartilage of C57B6J mice and expanded. The expanded auricular chondrocytes (10×106 cells/cm3) were seeded onto the gelatin sponges, which served as scaffolds. The construct assembly was implanted in the subcutaneous space of mice through a syngeneic fashion. Thereafter, constructs were retrieved at 2, 4, or 6 weeks.

Results: (1) Morphology: The size of implanted constructs was larger than the size of the scaffold with 500, 1000, and 2000 μg/cm3 b-FGF-impregnated gelatin sponges incorporating β-TCP at 4 and 6 weeks after implantation. (2) The weight of the constructs increased roughly proportional to the increase in volume of the b-FGF-impregnated scaffold at 2, 4, and 6 weeks after implantation, except in the 2000 μg/cm3 b-FGF-impregnated constructs group. (3) Histological examination: Extracellular matrix in the center of the constructs was observed in gelatin sponges impregnated with more than 100 μg/cm3 b-FGF at 4 weeks after implantation. The areas of cells with an abundant extracellular matrix were positive for cartilage-specific marker type 2 collagen in the constructs. (4) Protein assay: Glycosaminoglycan and collagen type 2 expression were significantly increased at 4 and 6 weeks on implantation of gelatin sponges impregnated with more than 100 μg/cm3 b-FGF. At 6 weeks after implantation, the ratio of type 2 collagen to type 1 collagen in constructs impregnated with 100 μg/cm3 or more b-FGF was higher than that in mice auricular cartilage.

Conclusion: Gelatin sponges impregnated with more than 100 μg/cm3 b-FGF incorporating β-TCP with chondrocytes (10×106 cells/cm3) can fabricate engineered cartilage at 4 weeks after implantation.

Introduction

Chondrocytes that had been proliferated in an in vitro culture and seeded onto a scaffold can fabricate cartilage architecture in an in vivo culture system.1 Chondrogenesis and the amount of produced cell matrix depend on the initial cell seeding density on the scaffold. High cell seeding density on the scaffold favors chondrogenesis and extracellular matrix formation in engineered cartilage.2 More than 50×106 cells/cm3 in cell density was necessary to induce chondrogenesis and extracellular matrix formation in engineered constructs.3 One month was required to result in a more than 100-fold increase in chondrocytes in in vitro monolayer cell cultures.1,4 These chondrocytes should be expanded until the necessary cell numbers in in vitro monolayer cell culture are obtained for the size of the engineered cartilage needed. Basic fibroblast growth factor (b-FGF) is a proliferation factor of chondrocytes in in vitro cell culture.5,6

Gospodarowicz7 identified that b-FGF is a promotion factor of fibroblasts in 1974. b-FGF is also known to induce potent angiogenesis, granulation tissue formation, and epithelization.8–11 Therefore, our culture medium containing b-FGF to proliferate chondrocytes in in vitro culture is changed twice a week.1,4 Once expanded, chondrocytes lose their original morphological and biological characteristics.1 Furthermore, proliferated cells had decreased ability of chondrogenesis and produced a decreased amount of extracellular matrix in in vivo culture according to the length of time of cell proliferation in in vitro cell monolayer culture.4 It is disadvantageous to engineer cartilage in an in vivo culture system using chondrocytes that had been proliferated in in vitro cell culture. Proliferation of chondrocytes in an in vitro culture system is tedious and requires special techniques.

Recently, the concept of engineered constructs has moved from in vitro three-dimensional (3D) culture systems such as a bioreactor, toward in situ regeneration in simple and realistic tissue engineering.12 Therefore, administration of a topical factor and recruitment or proliferation of cells are vital for in situ regeneration.

Exogenously administered b-FGF binds heparan sulfate in extracellular matrix stably, and this binding is released by an enzyme. b-FGF is rapidly cleared, with a serum half life of less than 60 min.13,14 Furthermore, after subcutaneous administration of b-FGF, a serum half life of around 2 h was reported.15 In the development of b-FGF as a drug, consecutive or intermittent application of a small amount of b-FGF was recommended for being most promising to attain a maximum rate of wound healing in a study in mice.16 Specifically, consecutive administration of 0.2–2 μg b-FGF per wound with an area of 1.6 cm2 was reported as optimal to accelerate open wound healing. In addition, this procedure is supported from a therapeutic point of view. However, repeated subcutaneous administration of a small amount of b-FGF by an in vivo culture system is complicated and not realistic for fabricating engineered cartilage constructs. An in vivo culture system consisting of a single subcutaneous mode of administration and sustained release of b-FGF is preferable to fabricate engineered cartilage. Therefore, technical development of a drug delivery system is necessary for in vivo regeneration.

Gelatin is a denatured, biodegradable protein obtained by acid and alkaline processing of collagen. When mixed with positively or negatively charged gelatin, an oppositely charged protein will ionically interact to form a polyion complex. Protein is released from charged gelatin matrices on the basis of this polyion complexation. Slow release of b-FGF with extended action could be achieved by this polyion complexation.17 In Japan, human recombinant b-FGF (Fiblast Spray®; Kaken Pharmaceutical, Tokyo, Japan) has been clinically used for the treatment of chronic skin ulcer since 2001. Preclinical and clinical studies of slow-release b-FGF have been reported for angiogenesis, wound healing, peripheral nerve regeneration, and tissue survival.18–26

Kanda et al.27,28 reported the optimal amount of slow-release b-FGF with gelatin sponge-based scaffold for skin wound defects. They concluded that gelatin sponge-based scaffold impregnated with 7–14 μg/cm2 b-FGF accelerated wound healing, and an excess amount of b-FGF did not increase the wound-healing efficacy of gelatin-based scaffold with slow-release b-FGF.

Isogai et al.29 first reported that a slow-release b-FGF system augments chondrogenesis in tissue-engineered cartilage constructs by using b-FGF-impregnated gelatin sponges in vivo. b-FGF-impregnated gelatin microspheres with slow release enhanced chondrogenesis in in situ engineered cartilage.29,30 The relationship between the amount of regenerative cartilage that forms and the amount of b-FGF impregnated in gelatin microspheres has not been clarified. This study investigated the optimal amount of b-FGF with gelatin sponges to fabricate engineered cartilage.

Materials and Methods

Cell harvest

All procedures in the present experiments were approved by the Animal Care Committee of our institution (protocol no. P11-010). Auricular cartilage was aseptically harvested from 3- to 4-week-old C57B6J mice (Japan SLC, Inc., Shizuoka, Japan). Chondrocytes were obtained as previously described.1,30 Briefly, the tissue surrounding the cartilage was removed by blunt and sharp dissection. A small piece of cartilage was minced into 1 mm3 pieces and digested by 0.3% collagenase type 2 (Worthington, Freehold, NJ) in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM; Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) at 37°C for 40 min. The digested suspension was filtered through a sterile 100 μm nylon cell strainer (BD Falcon, Bedford, MA) and centrifuged at 430 g at 4°C for 5 min. The resulting cell pellet was washed with phosphate-buffered saline (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Osaka, Japan). For monolayer cultures, the isolated cells were seeded into a collagen type 1-coated culture dish (Asahi Glass Co., Funabashi, Japan) at a density of 6400 cells/cm2 and cultured in DMEM/F12 (Sigma Chemical Co.) containing 5% human serum (Sigma) supplemented with 100 ng/mL fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2; Kaken Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd.) and 5 μg/mL insulin, as previously reported.1,30 Throughout all experiments, the medium was changed twice a week.

Scaffold

Gelatin sponges incorporating β-tricalcium phosphate (β-TCP) were prepared by chemical cross-linking of gelatin with glutaraldehyde in the presence of β-TCP at a 25% amount. Briefly, 3 wt% aqueous solution of gelatin containing a 25% amount of β-TCP was mixed at 5000 rpm at 37°C for 3 min by using a homogenizer. After 0.16% of glutaraldehyde aqueous solution was added to the mixed solution, the β-TCP-dispersed gelatin solution was further mixed for 15 s by the homogenizer. The resulting foamy solution was cast into a polypropylene dish of 138×138 cm2 and 5 mm depth, and maintained at 4°C for 12 h for gelatin cross-linking. Then, the cross-linked sponges were placed in 100 mM aqueous glycine solution at 37°C for 1 h to block the residual aldehyde groups of glutaraldehyde, thoroughly washed with double-distilled water, and freeze dried, followed by cutting into a column of 4 mm in diameter and 1.25 mm in height. The scaffold volume was 60 mm3.

Construct assembly

Human recombinant fibroblast growth factor-2 (b-FGF) (0, 10, 100, 500, 1000, or 2000 μg/cm3; Kaken Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd.) dissolved in 10 μL of distilled water was incubated with the scaffold (lyophilized gelatin sponges incorporating β-TCP) and kept at room temperature for 30 min before use.

Cell seeding into gelatin sponges incorporating β-TCP

Expanded auricular chondrocytes were collected by treatment with 0.05% trypsin-EDTA (Sigma) and counted in a hemocytometer. 7×105 collected chondrocytes (10×106 cells/cm3) in DMEM were seeded onto the scaffold-shaped column just before implantation.1,30

Implantation

One piece of the gelatin sponges incorporating β-TCP with auricular chondrocytes was implanted subcutaneously in a C57B6J mouse (Japan SLC, Inc.) under general anesthesia by halothane (Takeda Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Osaka, Japan).

Retrieval of constructs

Thereafter, constructs with auricular chondrocytes were retrieved at 2, 4, or 6 weeks after implantation. Their biochemical properties as well as their histology were examined.

Morphological and histological examinations

Engineered specimens were harvested for morphological, histological, and biochemical analyses at 2, 4, or 6 weeks postimplantation. The engineered specimens were weighed, and their sizes were measured. Each construct was cut in half. The half-size specimens were embedded in Tissue-Tek OCT compound 4583 (Sakura Fine Technical Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) and frozen. They were then cut into 7.5 μm sections to assess the engineered cartilage. The sections were stained with toluidine blue to detect metachromasia and chondrogenic tissue, as well as with hematoxylin and eosin staining.

Immunohistochemical staining

Before staining, sections were warmed at room temperature for 30 min and then fixed in ice-cold 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min. Sections were incubated with 2% bovine serum block for 60 min. Mouse anticollagen type 1 (1:200; Novus Biologicals LLC, Littleton, CO), anticollagen type 2 (1:200; LSL Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), or anticollagen type 10 antibody (1:500; Abbiotec LLC, San Diego, CA) was applied to the sections as the primary antibody overnight at 4°C in duplicate. Sections incubated with anticollagen type 1 or 10 were then incubated with the secondary antibody Alexa Fluor® 488 Dye (1:500; Life Technologies Japan, Tokyo, Japan) for 60 min. Sections incubated with anticollagen type 2 were then incubated with the secondary antibody Alexa Fluor® 594 Dye (1:500; Life Technologies Japan) for 60 min.

Protein assay

The other half-size engineered constructs were dissolved in 10 mg/mL pepsin/0.05 M acetic acid at 4°C for 48 h, and then in 1 mg/mL pancreatic elastase/1× TSB at 4°C overnight. The samples were centrifuged at 9100 g at 4°C for 5 min to remove the residue.

The sulfated glycosaminoglycan (GAG) content was measured using Alcian blue-binding assay (Wieslab AB, Lund, Sweden). After digestion of the atelocollagen pellet containing chondrocytes in 0.3% collagenase at 37°C for 1 h, cell debris and insoluble material were removed by centrifugation at 6000 g at 4°C for 30 min. GAG in the supernatant was precipitated with Alcian blue solution, and the sediments obtained by centrifugation at 6000 g at 4°C for 15 min were dissolved again in 4 M GuHCl-33% propanol solution. The spectrophotometric absorbance of the mixture was measured at a wavelength of 600 nm.

The collagen proteins in the cell/gel construct were solubilized and quantified by ELISA according to the protocol of the Type I and Type II Collagen Detection Kit (Chondrex, Redmond, WA). The cell/gel construct was dissolved in 10 mg/mL pepsin/0.05 M acetic acid at 4°C for 48 h and then in 1 mg/mL pancreatic elastase/1×TSB at 4°C overnight. In the mixture, the collagen proteins were captured by polyclonal anti-human type I or type II collagen antibodies and detected by biotinylated counterparts and streptavidin peroxidase. OPD and H2O2 were added to the mixture, and the spectrophotometric absorbance of the mixture was measured at a wavelength of 490 nm.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of constructs' weight was performed by the Tukey test, and statistical analysis of the amount of protein was performed by the Bonferroni test using commercially available IBM SPSS Statistics 21 software (IBM, Armonk, NY). p-Values of less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Gross appearance

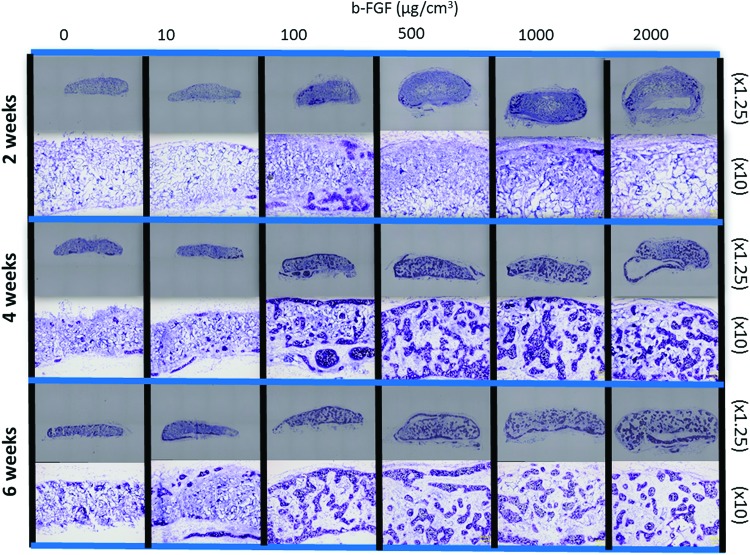

At 2 weeks after implantation, the constructs were covered by white fibrous tissue and the implanted constructs were approximately the same size as the scaffolds (Fig. 1). At 4 and 6 weeks after implantation, the implanted constructs were larger than the scaffold with 500, 1000, or 2000 μg/cm3 b-FGF-impregnated gelatin sponges incorporating β-TCP.

FIG. 1.

Photographs of the constructs at 2, 4, or 6 weeks after implantation of a scaffold with 0, 10, 100, 500, 1000, or 2000 μg/cm3 b-FGF -impregnated gelatin sponge incorporating β-TCP. At 2 weeks after implantation, constructs were covered by white fibrous tissue and the size of the implanted constructs was approximately the same as the size of the scaffolds. At 4 weeks and 6 weeks after implantation, the size of the implanted constructs was larger than the size of the scaffold with 500, 1000, and 2000 μg/cm3 b-FGF-impregnated gelatin sponges incorporating β-TCP. b-FGF, basic fibroblast growth factor; β-TCP, β-tri-calcium-phosphate. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

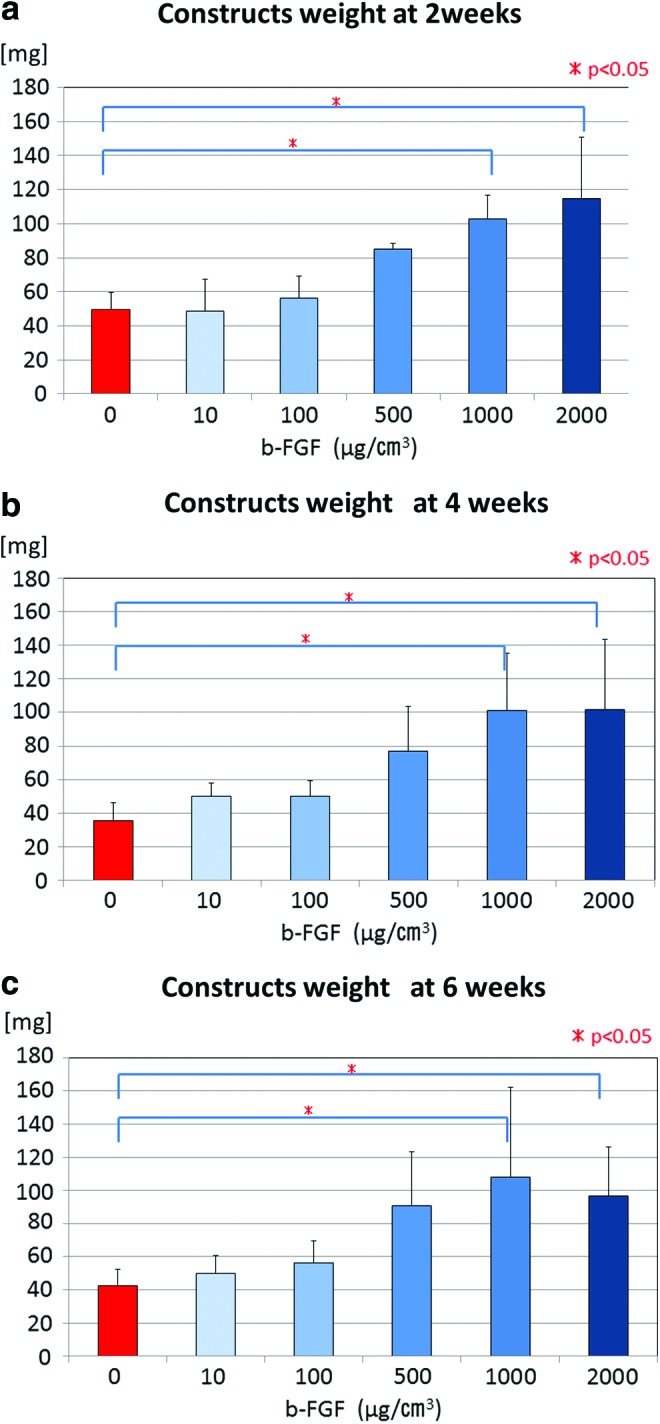

Constructs' weight

At 2 weeks after implantation, the constructs' weight had increased roughly proportional to the volume of the b-FGF-impregnated scaffold (Fig. 2a). The 1000 and 2000 μg/cm3 b-FGF-impregnated constructs were significantly heavier than the non b-FGF-impregnated constructs at 2 weeks after implantation. The weight of the 1000 μg/cm3 b-FGF-impregnated constructs was maintained at 4 and 6 weeks after implantation, although the weight of the 2000 μg/cm3 b-FGF-impregnated constructs decreased slightly at 4 and 6 weeks compared with that at 2 weeks (Fig. 2b, c). The 1000 and 2000 μg/cm3 b-FGF-impregnated constructs remained significantly heavier than the non-b-FGF-impregnated constructs at 4 and 6 weeks after implantation.

FIG. 2.

Weight of the constructs at 2, 4, or 6 weeks after implantation of a scaffold with 0, 10, 100, 500, 1000, or 2000 μg/cm3 b-FGF -impregnated gelatin sponge incorporating β-TCP. At 2 weeks after implantation (a), the weight of the constructs increased roughly proportional to the volume of the b-FGF-impregnated scaffold. These weights were maintained at 4 weeks (b) and 6 weeks (c) after implantation except in the 2000 μg/cm3 b-FGF-impregnated constructs group. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

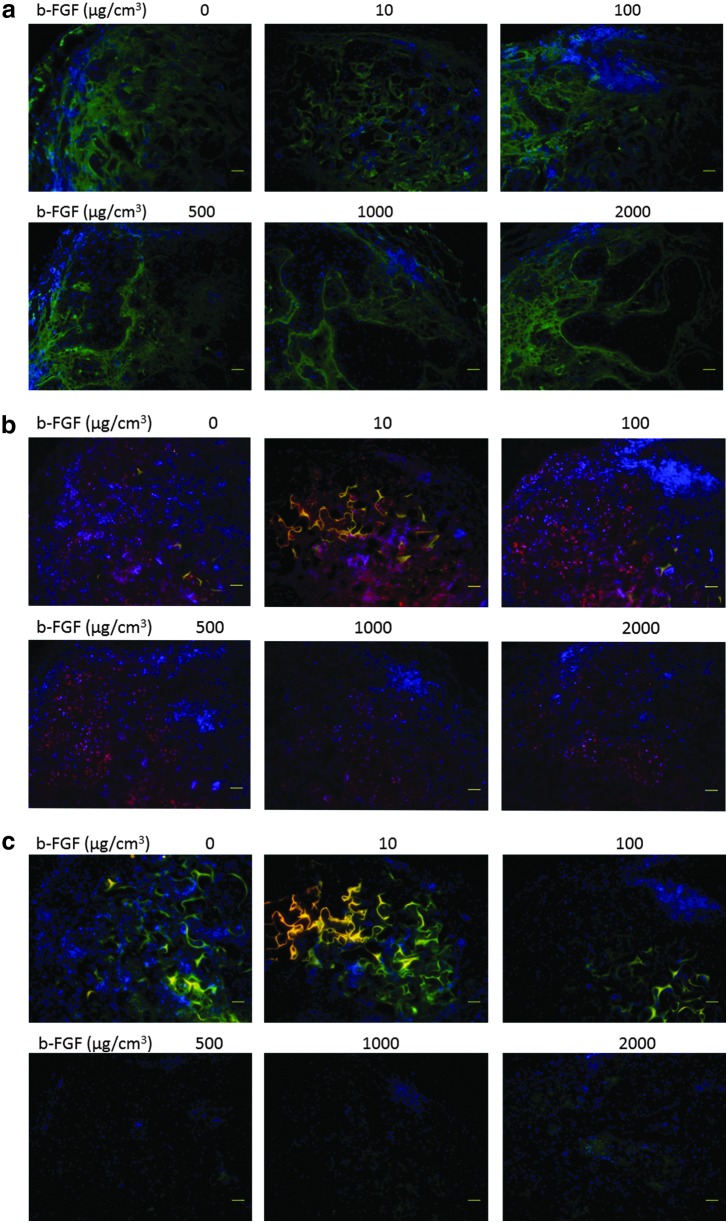

Histological findings

At 2 weeks after implantation, the presence of metachromasia and chondrogenic tissue was confirmed on the surface of engineered constructs that had been impregnated with 100 μg/cm3 or more b-FGF (Fig. 3). There was a mucinous solution in the middle portion of the engineered constructs of the 2000 μg/cm3 impregnated constructs group. Extracellular matrix was observed in the center of the constructs using gelatin sponges impregnated with 100 μg/cm3 or more b-FGF at 4 weeks after implantation.

FIG. 3.

Microscopic images of the constructs. At 2 weeks after implantation, the presence of metachromasia and chondrogenic tissue on the surface of the engineered constructs was confirmed in the 100 μg/cm3 or more b-FGF-impregnated constructs groups. There was a mucinous solution in the middle portion of the engineered constructs in the 2000 μg/cm3 impregnated constructs group. Extracellular matrix in the center of the constructs was observed using gelatin sponges impregnated with 100 μg/cm3 or more b-FGF at 4 weeks after implantation. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

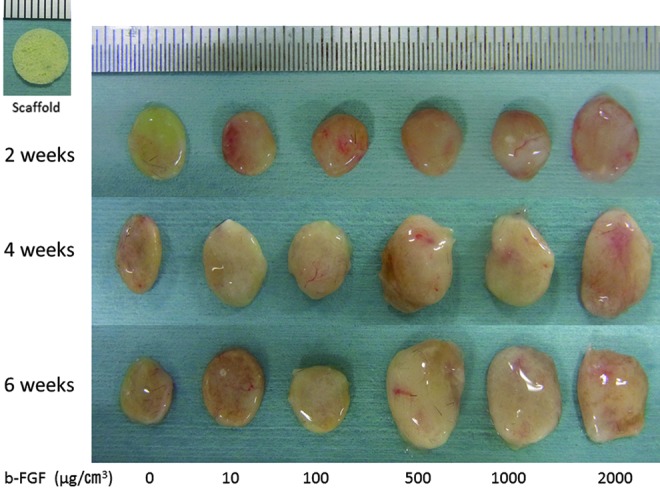

Immunohistochemical staining findings

At 6 weeks after implantation, the circumference of the engineered cartilage was positive for type 1 collagen (Fig. 4). The type 1 collagen-positive area did not differ among the samples impregnated with various amounts of b-FGF. The areas of cells with abundant extracellular matrix were positive for cartilage-specific marker type 2 collagen in the constructs. The area of collagen type 2 expression was larger in each group impregnated with 100 μg/cm3 or more b-FGF than in the non-b-FGF-impregnated group at 6 weeks. A few areas of collagen type 10 expression were observed in each group impregnated with 1000 μg/cm3 or more b-FGF.

FIG. 4.

Immunohistochemical staining findings at 6 weeks (a) Type 1 collagen staining, (b) Type 2 collagen staining, and (c) Type 10 collagen staining. At 6 weeks after implantation, the circumference of the engineered cartilage matrix was positive for type 1 collagen. The amount of impregnated b-FGF did not affect the area that was positive for type 1 collagen. The areas of cells with abundant extracellular matrix were positive for cartilage-specific marker type 2 collagen in the constructs. A few areas of collagen type 10 expression were observed in each group impregnated with 1000 μg/cm3 or more b-FGF at 6 weeks.

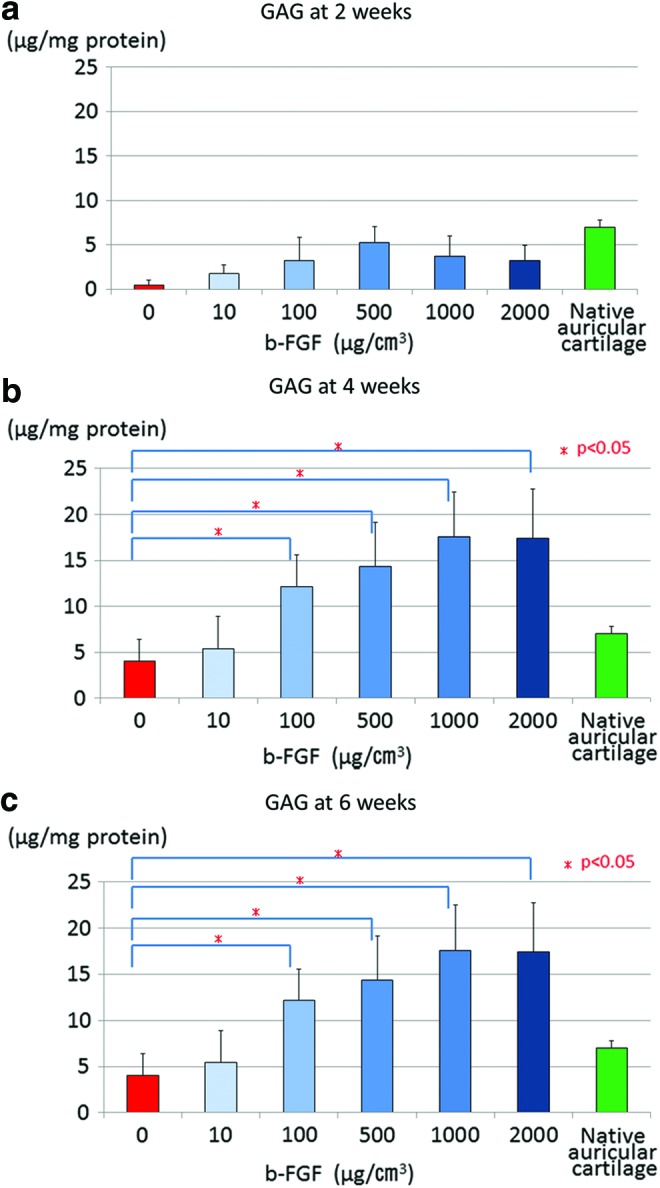

Protein assay

The level of glycosaminoglycan expression was significantly higher in the groups impregnated with 100 μg/cm3 or more b-FGF compared with the non-b-FGF-impregnated group at 4 and 6 weeks after implantation (Fig. 5a–c). Furthermore, the level of glycosaminoglycan expression was significantly higher in each group impregnated with 100 μg/cm3 or more b-FGF at 4 and 6 weeks after implantation than in the auricular cartilage of 4-week-old mice that served as a control (Fig. 5a–c).

FIG. 5.

Glycosaminoglycan (GAG) expression in the engineered constructs at 2, 4, and 6 weeks after implantation (a) 2 weeks, (b) 4 weeks, and (c) 6 weeks. GAG expression was significantly higher in the groups impregnated with 100 μg/cm3 or more b-FGF than in the non-b-FGF-impregnated group at 4 and 6 weeks after implantation. Furthermore, the level of glycosaminoglycan expression in each group impregnated with 100 μg/cm3 or more b-FGF at 4 and 6 weeks after implantation was higher than that in auricular cartilage of 4-week-old mice, which served as the control. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

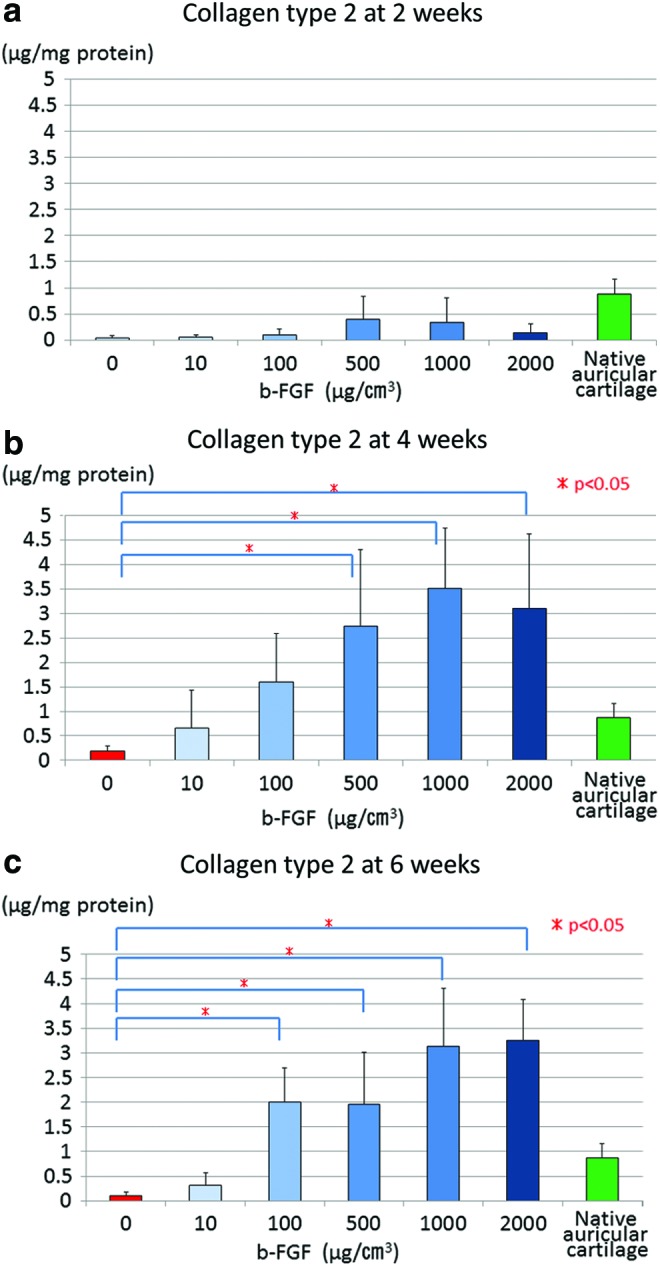

The level of collagen type 2 expression was significantly higher in each group impregnated with 500 μg/cm3 or more b-FGF than in the non-b-FGF-impregnated group at 4 weeks after implantation. At 6 weeks after implantation, the level of collagen type 2 expression was significantly higher in each group impregnated with 100 μg/cm3 or more b-FGF than in the non-b-FGF-impregnated group (Fig. 6a–c). At 4 weeks and 6 weeks after implantation, the level of collagen type 2 expression in each group impregnated with 100 μg/cm3 or more b-FGF was higher than that in mice auricular cartilage, which served as a control (Fig. 6a–c).

FIG. 6.

Collagen type 2 expression in the engineered constructs at 2, 4, and 6 weeks after implantation (a) 2 weeks, (b) 4 weeks, and (c) 6 weeks. The level of collagen type 2 expression was also significantly higher in each group impregnated with 500 μg/cm3 or more b-FGF than in the non-b-FGF-impregnated group at 4 weeks after implantation. At 6 weeks after implantation, it was significantly higher in each group impregnated with 100 μg/cm3 or more b-FGF than in the non-b-FGF-impregnated group. The level of collagen type 2 expression in the auricular cartilage of normal mice, which served as a control, is lower than that in each group impregnated with 100 μg/cm3 or more b-FGF at 4 weeks and 6 weeks after implantation. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

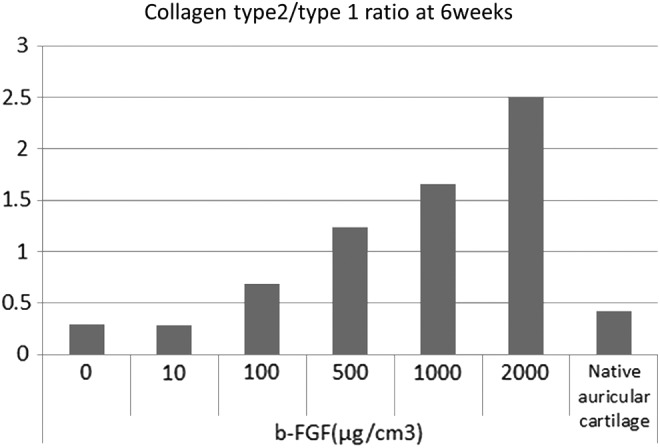

At 6 weeks after implantation, the ratio of type 2 collagen to type 1 collagen in each group impregnated with 100 μg/cm3 or more b-FGF was higher than that in mice auricular cartilage, which had been obtained in the same manner as that described for cell harvest. The ratio of type 2 collagen to type 1 collagen was positively correlated with the amount of impregnated b-FGF. Moreover, the maximal ratio was observed in the group impregnated with 2000 μg/cm3 b-FGF (Fig. 7).

FIG. 7.

The ratio of type 2 collagen to type 1 collagen at 6 weeks after implantation. The ratio of type 2 collagen to type 1 collagen in native auricular cartilage, which served as the control, was around 0.4. The ratio in 100 μg/cm3 or more b-FGF-impregnated constructs was higher than that in native auricular cartilage. The ratio of type 2 collagen to type 1 collagen was positively correlated with the amount of impregnated b-FGF.

Discussion

We found that gelatin sponges impregnated with 100 μg/cm3 or more b-FGF and incorporating β-TCP with chondrocytes (10×106 cells/cm3) can fabricate engineered cartilage by 4 weeks after implantation. Furthermore, we showed that the amount of impregnated b-FGF on gelatin sponges incorporating β-TCP was correlated with the amount of chondrogenesis and produced cell matrix in this study. This means that the degree of chondrogenesis and amount of produced cell matrix can be controlled by the amount of b-FGF impregnated in gelatin sponges incorporating β-TCP in the scaffold. The size of the engineered constructs was the same as the scaffold size with 100 μg/cm3 b-FGF-impregnated gelatin sponges incorporating β-TCP. The engineered constructs with 500 μg/cm3 or more b-FGF-impregnated gelatin sponges incorporating β-TCP were larger than the scaffold. The size and shape of the engineered cartilage can be controlled by 100 μg/cm3 b-FGF-impregnated gelatin sponges incorporating β-TCP with proliferated chondrocytes.

Gelatin is an excellent scaffold in terms of biocompatibility and biodegradability, and it has been used as a drug delivery system to carry out the sustainable release of various growth factors in the clinical field.31 Gelatin sponge has been reported as a useful scaffold material to engineer cartilage formation.32,33 However, the gelatin construct scaffold contracted significantly in in vitro culture systems.34 To solve these problems with gelatin, we have newly developed the gelatin β-TCP sponge.35,36 β-TCP has biodegradation properties, and has an advantage in generating engineered cartilage.37 β-TCP incorporation increased the compression modulus of the gelatin sponge without causing any change in the pore structure. The compression modulus of sponges increased in size with the amount of β-TCP.35,36 Osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells became maximal for the sponge with a β-TCP amount of 50 wt%.35 According to our basic study, the gelatin sponge with a β-TCP amount of 25 wt%, which was the most efficient in regenerating cartilage tissue, was used for the scaffold in this study.

A density of 10×106 cell/cm3 chondrocytes onto gelatin sponges incorporating β-TCP without slow-release b-FGF could not form engineered cartilage in an in vivo culture system in this experiment. However, the use of 100 μg/cm3 b-FGF-impregnated gelatin sponges incorporating β-TCP could result in the formation of engineered cartilage in the same in vivo culture system. Furthermore, 100 μg/cm3 or more b-FGF-impregnated gelatin could enhance chondrogenesis in the in vivo culture system. Seeding cell densities from 2×106 to 125×106 chondrocytes/cm3 were evaluated for cartilage tissue engineering using the scaffold system without slow-release b-FGF.38–40 A porous scaffold with atelocollagen and high seeding chondrocyte density can maintain the size of the tissue-engineered cartilage and realize moderate cartilage regeneration.3 Constructs using 50×106 or 100×106 cells/cm3 in cell density can form engineered cartilage more readily than 0.1×106 and 1×106 cells/cm3 due to the limitation in the sizes of the chondrocytes. Seeding of high cell density is advantageous for engineered cartilage without slow-release b-FGF. High-seeding cell density on the scaffold can induce a high level of chondrogenesis and production of a large amount of extracellular matrix in engineered cartilage.2 This study showed that a seeding density of 10×106 cells/cm3 could result in a high cell density in a scaffold implanted into the subcutaneous area by slow-release b-FGF impregnated in gelatin sponge incorporating β-TCP. In addition, b-FGF induces the growth of vascular endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells.8 Subcutaneous implantation of b-FGF-incorporating gelatin hydrogels into mice induced significant neovascularization.17 Neovascularization by induced b-FGF could accelerate the fabrication of tissues and organs in vivo.

Isogai et al.29 first reported that a slow-release b-FGF system can augment chondrogenesis in tissue-engineered cartilage constructs by using b-FGF-impregnated gelatin sponges. They used 100 μg b-FGF per construct to fabricate engineered cartilage with 100×106 chondrocytes per construct. However, the amount of b-FGF per scaffold volume had not been mentioned in that report. Komura et al.30 in our group had used the same slow-release b-FGF system to fabricate an engineered cartilage plate in the airway. They had administered 1666 μg/cm3 (scaffold volume) b-FGF onto engineered scaffold with 10×106 chondrocytes/cm3. Isogai et al. developed a composite scaffold to fabricate a complicated 3D engineered auricular cartilage with a slow-release b-FGF system.29,41,42 From ∼50 to 80 μg/cm3 b-FGF had been impregnated onto gelatin sponges. The enhanced vascular networks41 induced by slow-release b-FGF and the proliferated chondrocytes are involved in enhanced chondrogenesis and production of extracellular matrix in cartilage regeneration. Isogai et al.42 showed that an appropriate number of seeded chondrocytes and early-stage cartilage regeneration by a slow-release b-FGF system with a fibrin spray coating can generate high-quality engineered cartilage. They had seeded 100×106 chondrocytes/mL onto the scaffold made of a complex of polyglycolic acid polymer and polypropylene. Isogai and colleagues41 had reported that impregnation of 160 μg b-FGF per 1 cm3 scaffold volume with gelatin enhances chondrogenesis and production of extracellular matrix.

This study showed that the amount of b-FGF impregnated in gelatin sponges incorporating β-TCP with seeded chondrocytes was correlated with the amount of matrix produced in an engineered cartilage at 2, 4, and 6 weeks after implantation. Our study is the first report demonstrating that cartilage with the desired volume and weight can be engineered by using gelatin hydrogel impregnated with the appropriate amount of b-FGF.

The engineered constructs had nearly the same size and shape as the scaffold when using 100 μg/cm3 b-FGF-impregnated gelatin sponges incorporating β-TCP. The use of 500 μg/cm3 or more b-FGF-impregnated gelatin sponges incorporating β-TCP with 10×106 seeded chondrocytes per 1 cm3 scaffold resulted in constructs that were larger than the scaffold. The proliferated chondrocytes in the scaffold by slow-release b-FGF had spilled out from the gelatin sponges incorporating β-TCP. Furthermore, the constructs in the 2000 μg/cm3 impregnated constructs group were larger than the scaffold, because there was a mucinous solution in the middle portion of the engineered constructs. The mucinous solution may be hyaluronic acid, which is produced by elastic chondrocytes.43 Nonwoven Poly glycolic polymer seeded at 100×106 chondrocytes/mL with slow-release b-FGF was about 7 times thicker than the same construct without slow-release b-FGF.41 Cellularity (cells/cm3) of bovine articular cartilage in an adult is 150×106 near the surface and 50×106 at a depth of 1.0 mm.44 Cellularity should be predetermined per volume in cartilage tissue. Impregnation with more than 500 μg/cm3 b-FGF with 10×106 seeding cell density induced overproduction of chondrocytes in the scaffold.

The levels of glycosaminoglycan and collagen type 2 in constructs impregnated with 100 μg/cm3 or more b-FGF were much higher than those in native auricular cartilage at 4 and 6 weeks after implantation. This means that impregnation with 100 μg/cm3 or more b-FGF led to accumulation of extracellular matrix, that is, the specific matrix for cartilage, in engineered cartilage.45 b-FGF can also proliferate fibroblasts7; therefore, our histological findings of engineered cartilage revealed a collagen type 1-positive area in the construct. Administration of slow-release b-FGF caused migration of fibroblasts from outside the scaffold and expanded the seeded chondrocytes in the construct. We showed that the ratio of type 2 collagen to type 1 collagen in mouse native auricular cartilage as a control was around 0.4. This mouse native auricular cartilage specimen was the same as the cell harvesting samples in our study. This auricular cartilage extirpated from the proximal ear is encircled with a fibrous layer of perichondrium, which consists of collagen type 1.46 Six weeks after implantation, the ratio of type 2 collagen to type 1 collagen in constructs impregnated with 100 μg/cm3 or more b-FGF was much higher than that in native auricular cartilage as a control. We revealed that this engineered cartilage with slow-release b-FGF was of higher quality than the original mouse auricular cartilage according to qualitative analysis of the ratio of type 2 collagen to type 1 collagen. Proliferated chondrocytes with slow-release b-FGF were more predominant than migrated fibroblasts with more than 100 μg/cm3 b-FGF in the construct.

Constructs with seeded chondrocytes on scaffolds and gelatin hydrogel sheets or nonwoven mesh incorporated with b-FGF had been implanted in vivo in previous reports.29,30,42 This gelatin hydrogel was placed onto the scaffold and slowly released b-FGF.29,30,42 In this study, the scaffold was made by gelatin hydrogel and β-TCP, and slowly released b-FGF. To make this scaffold, b-FGF was first integrated into the scaffold made by gelatin with β-TCP. Then, chondrocytes were seeded onto the scaffold with embedded b-FGF. This single individual scaffold for engineered cartilage has multiple functions of cell delivery and slow-release drug delivery at the engineering location. b-FGF, insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) are proliferative factors for chondrocytes.47 We used slow-release b-FGF by gelatin incorporated with β-TCP as a chondrocyte proliferation factor administered into a scaffold with chondrocytes. b-FGF (Kaken Pharmacy Co. Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) has been authorized by the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare in Japan as a wound-healing accelerator. Therefore, in Japan, b-FGF can be used as a proliferation factor for chondrocytes in a human culture system to engineer cartilage tissue in clinical situations without complicated ethical committee procedures. Sustained release of b-FGF in the scaffold proliferated chondrocytes in the in vivo culture system and was able to induce cartilage matrix formation in the early stage. This engineered cartilage regeneration system can achieve high cell density in the scaffold in a premature engineering stage in vivo. Therefore, the seeding cell number onto the scaffold could be reduced by a system of sustained release of b-FGF in engineering. The low cost and short period of cell culture using this method will be able to reduce the shortage in engineered cartilage. Cartilage tissue engineering for clinical application can be realized by using a slow-release b-FGF system in an in vivo culture system of the scaffold.

Conclusion

Tissue-engineered constructs in the clinical course can be realized by an in vivo culture system that currently makes use of regenerative capacity. A drug delivery system with sustained release in vivo is useful and easy to administer for an in vivo engineered system. This technique promotes in situ regeneration. Furthermore, a combination with cytokine administration would be beneficial for tissue engineering.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the grant titled “Tracheoplasty by combined growth factor and chondrocyte implantation,” JSPS KAKEN Grant Number 23592625. The authors appreciate the technical support provided by Nobuyuki Kikuchi, a technician in the Department of Tissue Engineering in the Graduate School of Medicine, University of Tokyo. The authors are thankful to Kaken Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd. for providing human recombinant fibroblast growth factor-2 (b-FGF).

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Komura M., Komura H., Tanaka Y., Kanamori Y., Sugiyama M., Nakahara S., Kawashima H., Suzuki K., Hoshi K., and Iwanaka T.Human tracheal chondrocytes as a cell source for augmenting stenotic tracheal segments: the first feasibility study in an in vivo culture system. Pediatr Surg Int 24,1117, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Talukdar S., Nguyen Q.T., Chen A.C., Sah R.L., and Kundu S.C.Effect of initial cell seeding density on 3D-engineered silk fibroin scaffolds for articular cartilage tissue engineering. Biomaterials 32,8927, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yamaoka H., Tanaka Y., Nishizawa S., Asawa Y., Takato T., and Hoshi K.The application of atelocollagen gel in combination with porous scaffolds for cartilage tissue engineering and its suitable conditions. J Biomed Mater Res A 93,123, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takahashi T., Ogasawara T., Kishimoto J., Liu G., Asato H., Nakatsuka T., Nakamura K., Kawaguchi H., Chung U.I., Takato T., and Hoshi K. Synergistic effects of FGF-2 with insulin or IGF-I on the proliferation of human auricular chondrocytes.) Cell Transplant 14,683, 2005 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Quatela V.C., Sherris D.A., and Rosier R.N.The human auricular chondrocyte. Responses to growth factors. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 119,32, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klagsbrun M., and Smith S.Purification of a cartilage-derived growth factor. J Biol Chem 255,10859, 1980 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gospodarowicz D.Localisation of a fibroblast growth factor and its effect alone and with hydrocortisone on 3T3 cell growth. Nature 249,123, 1974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gospodarowicz D., Ferrara N., Schweigerer L., and Neufeld G.Structural characterization and biological functions of fibroblast growth factor. Endocr Rev 8,95, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Presta M., Moscatelli D., Joseph-Silverstein J., and Rifkin D.B.Purification from a human hepatoma cell line of a basic fibroblast growth factor-like molecule that stimulates capillary endothelial cell plasminogen activator production, DNA synthesis, and migration. Mol Cell Biol 6,4060, 1986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sprugel K.H., McPherson J.M., Clowes A.W., and Ross R.Effects of growth factors in vivo. I. Cell ingrowth into porous subcutaneous chambers. Am J Pathol 129,601, 1987 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O'Keefe E.J., and Chiu M.L.Stimulation of thymidine incorporation in keratinocytes by insulin, epidermal growth factor, and placental extract: comparison with cell number to assess growth. J Invest Dermatol 90,2, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bader A., and Macchiarini P.Moving towards in situ tracheal regeneration: the bionic tissue engineered transplantation approach. J Cell Mol Med 14,1877, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edelman E.R., Nugent M.A., and Karnovsky M.J.Perivascular and intravenous administration of basic fibroblast growth factor: vascular and solid organ deposition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 90,1513, 1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lazarous D.F., Shou M., Stiber J.A., Dadhania D.M., Thirumurti V., Hodge E., and Unger E.F.Pharmacodynamics of basic fibroblast growth factor: route of administration determines myocardial and systemic distribution. Cardiovasc Res 36,78, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Furukawa A., Yugeuji T., Nakamura K., Nagashima Y., and Awaji T. Serum level profiles of recombinant human basic fibroblast growth factor. Kiso Rinsho 30,1579, 1996. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 16.Okumura M., Okuda T., Nakamura T., and Yajima M.Accerelation of wound healing in diabetic mice fibroblast growth factor. Biol Pharm Bull 19,530, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tabata Y., Nagano A., and Ikada Y.Biodegradation of hydrogel carrier incorporating fibroblast growth factor. Tissue Eng 5,127, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miyoshi M., Kawazoe T., Igawa H., Tabata Y., Ikada Y., and Suzuki S.Effects of bFGF incorporated into a gelatin sheet on wound healing. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed 16,893, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marui A., Tabata Y., Kojima S., Yamamoto M., Tambara K., Nishina T., Saji Y., Inui K., Hashida T., Yokoyama S., Onodera R., Ikeda T., Fukushima M., and Komeda M.A novel approach to therapeutic angiogenesis for patients with critical limb ischemia by sustained release of basic fibroblast growth factor using biodegradable gelatin hydrogel: an initial report of the phase I-IIa study. Circ J 71,1181, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takemoto S., Morimoto N., Kimura Y., Taira T., Kitagawa T., Tomihata K., Tabata Y., and Suzuki S.Preparation of collagen/gelatin sponge scaffold for sustained release of bFGF. Tissue Eng Part A 14,1629, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hashimoto T., Koyama H., Miyata T., Hosaka A., Tabata Y., Takato T., and Nagawa H.Selective and sustained delivery of basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) for treatment of peripheral arterial disease: results of a phase I trial. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 38,71, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kusuhara H., Itani Y., Isogai N., and Tabata Y. Randomized controlled trial of the application of topical b-FGF-impregnated gelatin microspheres to improve tissue survival in subzone II fingertip amputations. J Hand Surg Eur Vol 36,455, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morimoto N., Yoshimura K., Niimi M., Ito T., Tada H., Teramukai S., Murayama T., Toyooka C., Takemoto S., Kawai K., Yokode M., Shimizu A., and Suzuki S.An exploratory clinical trial for combination wound therapy with a novel medical matrix and fibroblast growth factor in patients with chronic skin ulcers: a study protocol. Am J Transl Res 4,52, 2012 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takagi T., Kimura Y., Shibata S., Saito H., Ishii K., Okano H.J., Toyama Y., Okano H., Tabata Y., and Nakamura M.Sustained bFGF-release tubes for peripheral nerve regeneration: comparison with autograft. Plast Reconstr Surg 130,866, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ito R., Morimoto N., Pham L.H., Taira T., Kawai K., and Suzuki S.Efficacy of the controlled release of concentrated platelet lysate from a collagen/gelatin scaffold for dermis-like tissue regeneration. Tissue Eng Part A 19,1398, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morimoto N., Yoshimura K., Niimi M., Ito T., Aya R., Fujitaka J., Tada H., Teramukai S., Murayama T., Toyooka C., Miura K., Takemoto S., Kanda N., Kawai K., Yokode M., Shimizu A., and Suzuki S.Novel collagen/gelatin scaffold with sustained release of basic fibroblast growth factor: clinical trial for chronic skin ulcers. Tissue Eng Part A 19,1931, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kanda N., Morimoto N., Ayvazyan A.A., Takemoto S., Kawai K., Nakamura Y., Sakamoto Y., Taira T., and Suzuki S.Evaluation of a novel collagen-gelatin scaffold for achieving the sustained release of basic fibroblast growth factor in a diabetic mouse model. J Tissue Eng Regen Med 8,29, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kanda N., Morimoto N., Takemoto S., Ayvazyan A.A., Kawai K., Sakamoto Y., Taira T., and Suzuki S.Efficacy of novel collagen/gelatin scaffold with sustained release of basic fibroblast growth factor for dermis-like tissue regeneration. Ann Plast Surg 69,569, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Isogai N., Morotomi T., Hayakawa S., Munakata H., Tabata Y., Ikada Y., and Kamiishi H.Combined chondrocyte-copolymer implantation with slow release of basic fibroblast growth factor for tissue engineering an auricular cartilage construct. J Biomed Mater Res A 74,408, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Komura M., Komura H., Kanamori Y., Tanaka Y., Suzuki K., Sugiyama M., Nakahara S., Kawashima H., Hatanaka A., Hoshi K., Ikada Y., Tabata Y., and Iwanaka T.An animal model study for tissue-engineered trachea fabricated from a biodegradable scaffold using chondrocytes to augment repair of tracheal stenosis. J Pediatr Surg 43,2141, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tabata Y.Biomaterial technology for tissue engineering applications. J R Soc Interface 6(Suppl 3),S311, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yaylaoglu M.B., Yildiz C., Korkusuz F., and Hasirci V.A novel osteochondral implant. Biomaterials 20,1513, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ponticiello M.S., Schinagl R.M., Kadiyala S., and Barry F.P.Gelatinbased resorbable sponge as a carrier matrix for human mesenchymal stem cells in cartilage regeneration therapy. J Biomed Mater Res 52,246, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leddy H.A., Awad H.A., and Guilak F.Molecular diffusion in tissue-engineered cartilage constructs: effects of scaffold material, time, and culture conditions. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater 70,397, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Takahashi Y., Yamamoto M., and Tabata Y.Osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells in biodegradable sponges composed of gelatin and b-tricalcium phosphate. Biomaterials 26,3587, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Takahashi Y., Yamamoto M., and Tabata Y.Enhanced osteoinduction by controlled release of bone morphogenetic protein-2 from biodegradable sponge composed of gelatin and b-tricalcium phosphate. Biomaterials 26,4856, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guo X., Wang C., Duan C., Descamps M., Zhao Q., Dong L., Lü S., Anselme K., Lu J., and Song Y.Q.Repair of osteochondral defects with autologous chondrocytes seeded onto bioceramic scaffold in sheep. Tissue Eng 10,1830, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ushida T., Furukawa K., Toita K., and Tateishi T.Three-dimensional seeding of chondrocytes encapsulated in collagen gel into PLLA scaffolds. Cell Transplant 11,489, 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hannouche D., Terai H., Fuchs J.R., Terada S., Zand S., Nasseri B.A., Petite H., Sedel L., and Vacanti J.P., Engineering of implantable cartilaginous structures from bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Tissue Eng 13,87, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Terada S., Yoshimoto H., Fuchs J.R., Sato M., Pomerantseva I., Selig M.K., Hannouche D., and Vacanti J.P.Hydrogel optimization for cultured elastic chondrocytes seeded onto a polyglycolic acid scaffold. J Biomed Mater Res A 75,907, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Morotomi T., Wada M., Uehara M., Enjo M., and Isogai N.Effect of local environment, fibrin, and basic fibroblast growth factor incorporation on a canine autologous model of bioengineered cartilage tissue. Cells Tissues Organs 196,398, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Enjo M., Terada S., Uehara M., Itani Y., and Isogai N.Usefulness of polyglycolic acid-polypropylene composite scaffolds for three-dimensional cartilage regeneration in a large-animal autograft model. Plast Reconstr Surg 131,335, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yokoyama A., Muneta T., Nimura A., Koga H., Mochizuki T., Hata Y., and Sekiya I.FGF2 and dexamethasone increase the production of hyaluronan in two-dimensional culture of elastic cartilage-derived cells: in vitro analyses and in vivo cartilage formation. Cell Tissue Res 329,469, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jadin K.D., Bae W.C., Schumacher B.L, and Sah R.L.Three-dimensional (3-D) imaging of chondrocytes in articular cartilage: growth-associated changes in cell organization. Biomaterials 28,230, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Park K.H., and Na K.Effect of growth factors on chondrogenic differentiation of rabbit mesenchymal cells embedded in injectable hydrogels. J Biosci Bioeng 106,74, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Le Guellec D., Mallein-Gerin F., Treilleux I., Bonaventure J., Peysson P., and Herbage D.Localization of the expression of type I, II and III collagen genes in human normal and hypochondrogenesis cartilage canals. Histochem J 26,695, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Danišovič L., Varga I., and Polák S.Growth factors and chondrogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells. Tissue Cell 44,69, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]