Abstract

Aims: Mitochondrial succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) is an essential complex of the electron transport chain and tricarboxylic acid cycle. Mutations in the human SDH subunit D frequently lead to paraganglioma (PGL), but the mechanistic consequences of the majority of SDHD polymorphisms have yet to be unraveled. In addition to the originally discovered yeast SDHD subunit Sdh4, a conserved homolog, Shh4, has recently been identified in budding yeast. To assess the pathogenic significance of SDHD mutations in PGL patients, we performed functional studies in yeast. Results: SDHD protein expression was reduced in SDHD-related carotid body tumor tissues. A BLAST search of SDHD to the yeast protein database revealed a novel protein, Shh4, that may have a function similar to human SDHD and yeast Sdh4. The missense SDHD mutations identified in PGL patients were created in Sdh4 and Shh4, and, surprisingly, a severe respiratory incompetence and reduced expression of the mutant protein was observed in the sdh4Δ strain expressing shh4. Although shh4Δ cells showed no respiratory-deficient phenotypes, deletion of SHH4 in sdh4Δ cells further abolished mitochondrial function. Remarkably, sdh4Δ shh4Δ strains exhibited increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, nuclear DNA instability, mtDNA mutability, and decreased chronological lifespan. Innovation and Conclusion: SDHD mutations are associated with protein and nuclear and mitochondrial genomic instability and increase ROS production in our yeast model. These findings reinforce our understanding of the mechanisms underlying PGL tumorigenesis and point to the yeast Shh4 as a good model to investigate the possible pathogenic relevance of SDHD in PGL polymorphisms. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 22, 587–602.

Introduction

Succinate dehydrogenase (SDH), also known as respiratory chain complex II, plays a crucial role in the tricarboxylic acid cycle and the electron transport chain. As an iron-sulfur flavoprotein, SDH catalyzes the energy-dependent oxidation of succinate to fumarate and transfers electrons to coenzyme Q in the respiratory electron transfer chain (53). The complex is located in the inner mitochondrial membrane and consists of SDHA, SDHB, SDHC, and SDHD subunits. SDHA and SDHB are hydrophilic subunits that form a catalytic domain, including FAD and several iron-sulfur subunits which catalyze the flow of electrons from succinate to the membrane dimer; SDHC and SDHD are transmembrane hydrophobic subunits that contain heme and sites for ubiquinone reduction.

Innovation.

Mutations in SDHD can cause paraganglioma (PGL), but how disruption of succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) function could lead to tumor formation has remained a mystery. Budding yeast Sdh4 and Shh4 are homologous to human SDHD. Previous studies demonstrate that Sdh4 is the major SDH subunit D in yeast. Our studies provide a possible role of a novel yeast mitochondrial protein, Shh4, as a better yeast model to study PGL tumorigenesis. We demonstrate that mutations of SDHD increase protein instability and a low protein expression level in PGL patients. These defective SDHD orthologs in budding yeast increase reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and nuclear and mitochondrial genomic mutations. Our findings indicate that SDHD mutations may lead to protein destabilization, mitochondrial damage, ROS production, genomic instability, and tumor formation.

Paraganglioma (PGL) is a rare neuroendocrine tumor derived from parasympathetic tissue of the head and neck, comprising 0.03% of all tumors (35). The clinical incidence is ∼0.001% (55). PGL frequently develops to a benign, highly vascular, slow-growing tumor, but may cause significant symptoms by compressing adjacent structures. The most common tumor location, the carotid body, is an oxygen sensor for hypoxia. It is located at the bifurcation of the carotid artery in the head and neck. SDHD mutations have also been observed in thoracic and pelvic locations in malignant PGL (65). PGL can occur sporadically or as a part of a hereditary syndrome. Familial PGL is associated with germline mutations in the mitochondrial complex II genes, and the familial incidence is ∼10–50% of PGLs (47). Among those mitochondrial complex II genes that cause familial PGL, SDHD is the most commonly mutated gene (5); in one report, a head and neck PGL was present in 97.7% of familial SDHD mutation carriers (8).

Models have been proposed that link succinate and reactive oxygen species (ROS) to SDH deficiencies and PGL tumorigenesis. Selak et al. proposed that SDH dysfunction leads to succinate accumulation and release from the mitochondria via the dicarboxylate carrier to inhibit the activity of the hypoxia-inducible factor α (HIFα) prolyl hydroxylases (PHDs) in the cytosol (56). Inhibition of HIFα PHD activity under normoxic conditions is known as the pseudo-hypoxic response, which results in the stabilization of HIFα by inhibiting the binding of the von Hippel-Lindau (pVHL) tumor suppressor protein to HIFα (40). The binding of VHL to HIFα is regulated by PHD-mediated hydroxylation at P402 and P564 on HIFα (27). HIFα that escapes degradation then migrates from the cytosol into the nucleus and transcriptionally activates its target genes, which are involved in proliferation, angiogenesis, metastasis, and cell survival (30). Another model proposed that the accumulated succinate might inhibit DNA demethylase. Finally, the pervasive DNA hypermethylation results in transcriptional silencing of multiple tumor suppressor genes (33, 37, 68). The dysfunctional SDH also triggers mitochondria to generate ROS, which may act as signaling molecules to promote tumor formation in SDH-deficient cells by inhibiting HIFα PHD activity under normoxic conditions, leading to a pseudo-hypoxic response (15, 18). However, it is controversial whether ROS can directly inactive PDH (20). Another model suggests that the accumulated ROS directly causes mitochondrial and nuclear DNA damage and tumorigenesis. Although complex II is not usually considered a major site for ROS production in the electron transport chain, evidence of an association between SDH mutations and oxidative stress, nuclear genomic instability, and tumorigenesis is accumulating (26, 43, 50, 61, 66). However, direct evidence of an SDHD-mediated mutation phenotype in tumorigenesis has not been reported.

The budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae is a powerful model organism for studying energy metabolism. The rapid shift from fermentative to respiratory growth benefits researchers investigating the molecular aspects of the events involved in metabolic pathways, particularly the functional consequences of gene mutations on enzymatic and respiratory activity. Yeast SDH, similar to its mammalian counterpart SDHA-SDHD, consists of four nuclear encoded subunits, Sdh1-Sdh4 (36), and the sequence similarities between yeast Sdh1-Sdh4 and human SDHA-SDHD are 65%, 67%, 23%, and 13%, respectively. Loss of SDH function in yeast results in an inability to grow on non-fermentable carbon sources such as ethanol, glycerol, or lactate (17, 46).

Here, we found that the expression of SDHD was markedly reduced or absent in SDHD-related carotid body tumor tissues and that this reduction was caused by SDHD mutations destabilizing the protein. We assess the pathogenic significance of the SDHD mutation identified in patients affected by PGL by performing functional studies in yeast. In our yeast model, we demonstrate that SDHD mutations cause protein instability, increase the production of ROS, and are associated with nuclear and mitochondrial genomic instability. These findings shed light on our understanding of the mechanisms underlying PGL tumorigenesis.

Results

Impaired protein stability causes a quantitative loss of SDHD protein expression in human cell lines and head and neck PGL patients

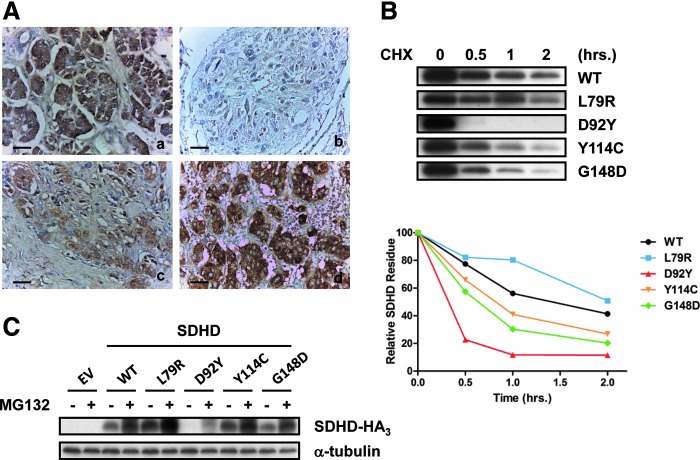

To assess SDHD expression in PGL patients, we investigated their SDHD protein expression using immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining (Fig. 1A). Six carotid body tumor specimens from patients with familial SDHD-mutation PGL showed weak or no staining of SDHD. Moreover, in 21 carotid body tumor samples from sporadic PGL patients, 10 showed weak or no staining, and six showed moderate staining of SDHD. Only five sporadic PGL patients displayed strong SDHD staining.

FIG. 1.

Impaired protein stability causes quantitative loss of SDHD protein expression in human cell lines and head and neck PGL patients. (A) Representative IHC staining of SDHD from familial (b) and sporadic (c, d) PGL patients. (a) Pancreas (a positive control); (b) absent; (c) moderate; (d) strong staining. Scale bar=50 μm. (B) The hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged wild-type and missense mutant SDHD proteins were expressed in human 293T cells. Protein synthesis was inhibited by CHX treatment for the indicated time points. SDHD was detected by an antibody against HA, and the bottom panel shows the relative amount of SDHD. (C) The wild-type and missense mutant SDHD proteins were expressed in human 293T cells, and the cells were subjected to dimethyl sulfoxide or MG132 treatment for 16 h. Expression of HA-tagged SDHD was detected by Western blot analysis using an HA antibody. α-tubulin was used as a control. CHX, cycloheximide; IHC, immunohistochemistry; PGL, paraganglioma; SDH, succinate dehydrogenase. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

We speculated that a defective gene in PGL patients might destabilize SDHD through increasing protein degradation. To test this hypothesis, we compared the protein stability of the wild-type and missense mutant SDHD proteins. Four missense mutations identified in PGL patients, L79R, D92Y, Y114C, and G148D, were created in SDHD. The wild-type and mutant SDHD were transfected into 293T cells, which were then treated with cycloheximide to inhibit protein synthesis. The protein stability of three of the four mutants (SDHD, D92Y, Y114C, and G148D) was lower than wild-type SDHD (Fig. 1B). To determine whether the instability of mutant SDHD is through ubiquitin-mediated degradation, wild-type and mutant SDHD-transfected 293T cells were treated with the protease inhibitor MG132. In the presence of MG132, the expression of mutant SDHDs was partially restored (Fig. 1C), indicating that proteasome-mediated degradation contributes to instability of the SDHD mutants. These results imply that the reduced SDHD protein expression in PGL patients may be due to increased SDHD degradation.

A novel yeast mitochondrial protein, Shh4/Ylr164w, has higher sequence conservation to human SDHD than Sdh4

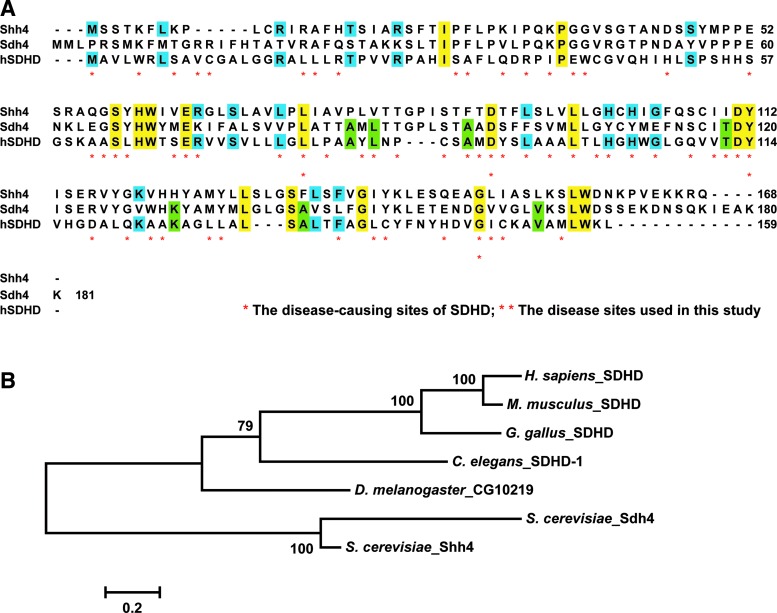

We conducted a BLAST search of human SDHD to the yeast protein database (SGD: http://yeastgenome.org/) and identified a novel yeast mitochondrial protein, Shh4/Ylr164w, with higher sequence conservation (19% of identity) to SDHD than Sdh4 (13% of identity) (Fig. 2A). These three proteins and other orthologous sequences were subjected to phylogenetic analysis. The genetic distance analysis revealed that human SDHD was closer to Shh4 (2.56) than to Sdh4 (3.69) (Fig. 2B). In addition to the high conservation between Shh4 and Sdh4 (46% of identity and 0.81 of genetic distance), a previous study found that Shh4 can form a respiration competent SDH isoenzyme with Sdh3 in sdh4Δ cells (64). Together, these results indicate that Shh4 have a function similar to function as human SDHD and yeast Sdh4.

FIG. 2.

A yeast mitochondrial novel protein, Shh4/Ylr164w, has a higher sequence conservation to human SDHD than Sdh4. (A) The amino-acid sequences of SDHD, Shh4, and Sdh4 were aligned by ClustalW2 (Hinxton; http://ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalw2/) using the default setting. Identical amino acids among all proteins are colored in yellow, blue shading indicates conserved residues between Shh4 and SDHD, and green shading indicates conserved residues between Sdh4 and SDHD. The disease associated sites of SDHD are labeled by asterisks, and the disease associated sites of SDHD used in this study are labeled by double asterisks. The identity between Shh4 and SDHD is 19%, whereas the identity between Sdh4 and SDHD is 13%. (B) The phylogenetic analysis of SDHD orthologs from different organisms, including sequences from Homo sapiens, Mus musculus, Gallus gallus, Caenorhabditis elegans, Drosophila melanogaster, and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. The analysis was conducted using the software package MEGA version 5.2. Molecular distances were calculated using the parameters of the Dayhoff model, and the tree was constructed using the Neighbor-Joining method with pairwise deletion. Statistical support was assessed by 1000 bootstrap replications. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

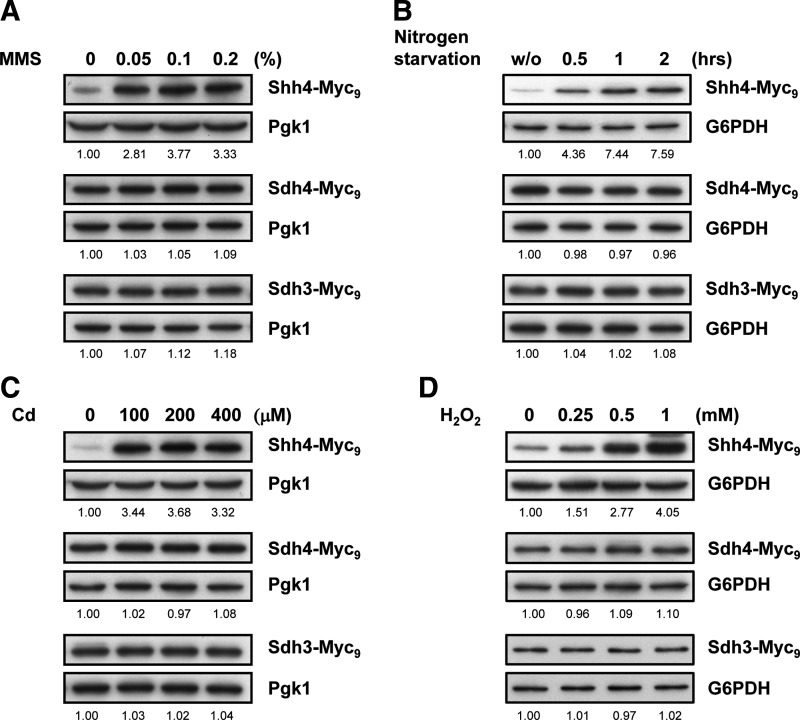

Shh4, but not Sdh4 and Sdh3, expression is increased under several stress conditions

A large-scale microarray database indicated that SHH4 expression increases under several stressful conditions, including fully aerobic, T2 toxin, nitrogen starvation, glucose limitation, cadmium (Cd), and methyl methanesulfonate (MMS) treatments (29, 34, 41, 51, 54, 59). We examined the expression level of Shh4 in three of those stress conditions. In addition, since Sdh4 is a mitochondrial protein, we also tested Shh4 expression under hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) treatment. Sdh3, Sdh4, and Shh4 were chromosomally tagged with nine copies of Myc for detection. We confirmed that the Myc tag introduced in these strains was neutral for respiratory competence by finding that the growth rate of the strains in glycerol was not affected compared with the untagged wild-type strain. Interestingly, Shh4, but not Sdh4 and Sdh3, expression was increased when cells were treated with MMS, nitrogen starvation, Cd, and H2O2 (Fig. 3). The Sdh3 ortholog Shh3 was also expressed under H2O2 (Supplementary Fig. S1A; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/ars). Since glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase is induced by MMS and Cd, we used Pgk1 as a loading control for these treatments (28, 69). These results indicate that Shh4, but not Sdh4 and Sdh3, is induced under stress. Although Shh4 was stress induced, neither shh4Δ nor other SDH subunit deletion mutants were more sensitive to oxidative stress (Supplementary Fig. S1B). Since we observed that Shh4 expression was increased under several stressors (Fig. 3), and because the mutation of SDHD to cause tumorigenesis is tissue specific in the carotid body and adrenal medulla, which consists of capillary endothelial cells, we speculated that SDHD expression might also be induced under stress in endothelial cells. To examine this possibility, we treated human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) with different dosages of H2O2. The expression of SDHD was, indeed, induced by H2O2 in a dose-dependent manner (Supplementary Fig. S1C), suggesting that oxidative stress induces SDHD expression.

FIG. 3.

Multiple stressors induce Shh4, but not Sdh4 and Sdh3, expression. Myc9-tagged yeast strains were subjected to several stressors. (A) MMS treatment. (B) Nitrogen starvation. (C) Cd treatment. (D) H2O2 treatment. Proteins were detected by Western blot analysis using an antibody against Myc. Pgk1 or G6PDH were used as controls. The band intensities displayed below each panel were quantified using Image J, normalized relative to respective internal controls, and expressed as the ratio of the Myc levels to the untreated group. Cd, cadmium; G6PDH, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase; H2O2, hydrogen peroxide; MMS, methyl methanesulfonate.

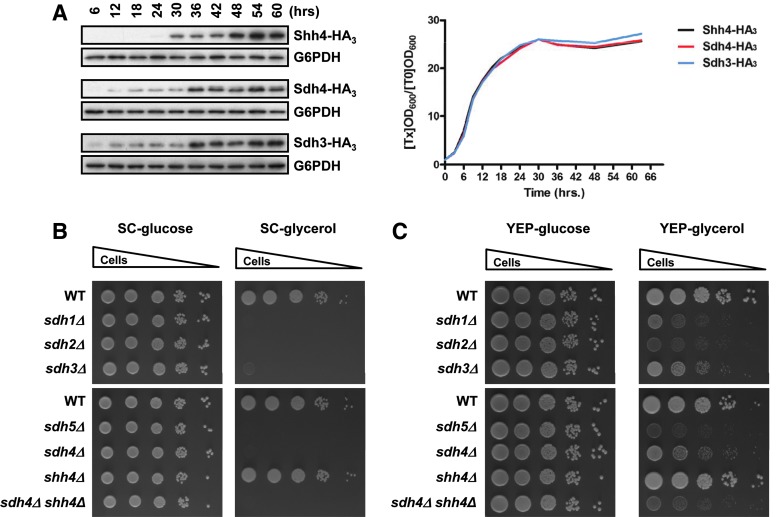

Shh4 is expressed in the post-diauxic shift phase and may play a functional role in yeast mitochondrial complex II

Yeast cells preferentially convert fermentable sugars as their carbon and energy sources. When yeast cells are grown in liquid culture, they metabolize glucose primarily by glycolysis, releasing ethanol to the medium. When the fermentable sugars are exhausted, the cells enter the diauxic shift, characterized by a slowed growth rate and the switch from glycolysis to aerobic utilization of a non-fermentable carbon source such as ethanol. When the non-fermentable carbon source is depleted from the medium, the cells enter the quiescent or stationary phase. SDH complex mutants of S. cerevisiae are viable in fermentable carbon sources, such as glucose. However, in non-fermentable carbon sources, such as glycerol, these mutants are not viable in synthetic complete (SC) medium and grow slowly in rich (YEP) medium.

According to previous research (32) and our cytosolic and mitochondrial fractionation results (Supplementary Fig. S2A), Shh4 is a mitochondrial protein. We speculated that Shh4 might be highly expressed when cells enter respiratory growth. The protein expression pattern of Shh4 was examined in a long-term culture. Shh4 was highly expressed after cells entered the post-diauxic shift phase (30 h, Fig. 4A; Supplementary Fig. S2B), indicating that Shh4 expression is greatly increased when cells enter aerobic respiration. This result suggests that Shh4 might play a functional role in respiratory growth.

FIG. 4.

Shh4 is expressed in the post-diauxic shift phase and may play a functional role in yeast mitochondrial complex II. (A) HA3-tagged strains were diluted to 0.2 at OD600 and grown at 30°C in YEP-glucose for 60 h. Cells were collected at 6-h intervals for 60 h, and protein expression was analyzed by Western blotting. The growth curves of these HA3-tagged strains are shown on the right. (B) A 10-fold diluted equal number of yeast was grown at 30°C on SC plates in the presence of glucose or glycerol. (C) A 10-fold diluted equal number of yeast was grown at 30°C on YEP plates in the presence of glucose or glycerol. SC, synthetic complete. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

The shh4Δ cells grew normally on SC medium with either glucose or glycerol as the carbon source (Fig. 4B). These results suggest that the deletion of SHH4 alone cannot block the mitochondrial respiratory pathway. Deletion of SDH4 slowed the respiratory growth rate in YEP-glycerol medium, and, surprisingly, deletion of SHH4 in sdh4Δ cells further decreased the growth rate of sdh4Δ cells (Fig. 4C). Taken together, these results suggest that Shh4 may contribute to mitochondrial function in YEP-glycerol and may be a functionally redundant protein for Sdh4 in yeast mitochondrial complex II.

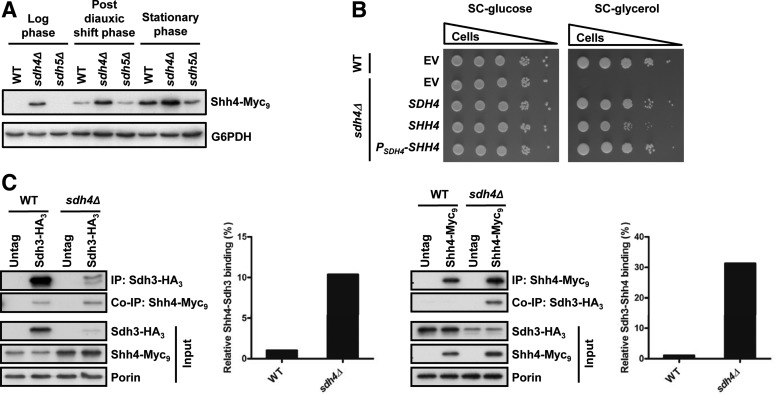

Shh4 can substitute for Sdh4 in sdh4Δ cells

To determine whether Shh4 can replace Sdh4 in the SDH complex, Shh4 expression was examined in sdh4Δ cells in the logarithmic, post-diauxic, and stationary phases. We consistently observed an increase in Shh4 expression in the sdh4Δ cells (Fig. 5A), implying that Shh4 may be induced to rescue the mitochondrial damage in sdh4Δ cells. To directly demonstrate that Shh4 is a functionally redundant protein of Sdh4, Shh4 was overexpressed from a high copy plasmid in sdh4Δ cells. Consistent with previous findings (64), in SC-glycerol medium, the expression of Shh4 driven by its own promoter (SHH4) or the SDH4 promoter (PSDH4-SHH4) complemented the growth defect of the sdh4 cells (Fig. 5B).

FIG. 5.

The Shh4 protein can substitute for Sdh4 in sdh4Δ cells. (A) Myc9-tagged SHH4 strains were grown in YEP-glucose to early log phase, post-diauxic shift phase, and stationary phase. The expression of Shh4 was detected by Western blot analysis. (B) The sdh4 mutant strain was complemented by the indicated plasmids and grown on SC-glucose or SC-glycerol plates. (C) Reciprocal co-immunoprecipitation between Shh4 and Sdh3. Immunoprecipitation of the indicated strains was conducted using an anti-HA antibody and an anti-Myc antibody to pull-down Sdh3 and Shh4, respectively, from mitochondrial extracts. Precipitated and co-precipitated proteins were analyzed by Western blotting using the indicated antibodies. The bar graphs shown at the bottom depict quantification of the relative amount of Shh4 and Sdh3 proteins that co-immunoprecipitate with Sdh3 and Shh4, respectively, in wild-type and sdh4Δ cells. EV, empty vector.

To determine whether Shh4 competes with Sdh4 binding to Sdh3 in the Sdh3-Sdh4 complex, the mitochondria from wild-type and sdh4Δ mutant cells were isolated, followed by co-immunoprecipitation of Sdh3. Sdh3 co-purified more Shh4 in sdh4Δ cells than in the wild-type cells. Reciprocal co-immunoprecipitation exhibited the same pattern; Shh4 co-purified more Sdh3 from Sdh4Δ cells than from the wild-type cells (Fig. 5C). Taken together, the Shh4 expression level is upregulated in the sdh4Δ mutant and Shh4 may substitute for Sdh4 to interact with Sdh3 for maintaining complex II function (Supplementary Fig. S3).

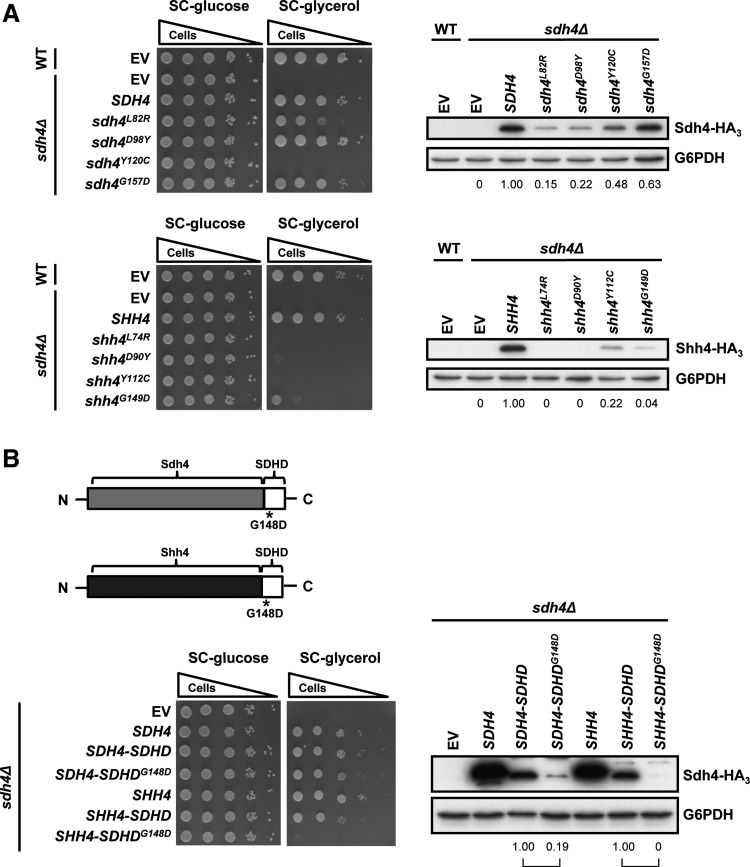

The conserved SDHD mutations found in patients trigger a more severe inhibition of respiratory growth in Shh4 than in Sdh4 by reducing protein stability

Others have used Sdh4 as a model to study the mechanisms of PGL formation (46). Owing to the high similarity of Sdh4 and Shh4, we speculated that an analysis of Shh4 might shed light on the role of SDHD in PGL. To address this hypothesis, we examined the pathogenic effects of the clinically identified SDHD mutations in hereditary PGL. Four missense mutations identified in PGL patients were created in Sdh4 and Shh4. These Sdh4 and Shh4 constructs, driven by the SDH4 promoter in sdh4Δ cells but not in shh4Δ cells, showed no growth defect on glycerol. Their protein levels were determined. To test the possible effects of these mutations, we examined their respiratory phenotypes. The sdh4Δ strains expressing sdh4 L82R, D98Y, and G157D grew on SC-glycerol plates; only Y120C, which is mutated at a conserved residue in the ubiquinone reductase active site (60), was unable to grow on SC-glycerol plates (Fig. 6A). In contrast, the sdh4Δ strains expressing shh4 L74R, D90Y, Y112C, or G149D showed a severe growth defect on glycerol plates (Fig. 6A). Since a high incidence of SDHD variants in Asian PGL patients contains a mutation in the first methionine codon causing a failure of protein expression (67), we surmised that the SDHD variants in many PGL patients might lose SDH function due to the reduction of SDHD expression. Examination of the protein expression levels showed that Shh4 mutant proteins were less stable than equivalent Sdh4 mutant proteins (Fig. 6A). These results suggest that Shh4 is suitable to serve as a model for mechanistic research in PGL and to shed light on the role of SDHD in PGL.

FIG. 6.

The conserved SDHD variants cause more severe inhibition in respiratory growth in Shh4 by affecting protein stability. (A) Various disease-causing mutations in SDHD were created in Sdh4 and Shh4 and expressed in sdh4Δ cells. Ten-fold diluted cultures were spotted on SC-glucose or SC-glycerol plates. The protein expression level of the plasmids was detected by Western blot analysis using an HA antibody. (B) Wild-type and various deficient SDHDs were domain swapped onto Sdh4 or Shh4 and expressed in sdh4Δ cells. Ten-fold diluted cultures were spotted on SC-glucose or SC-glycerol plates. The protein expression level of the plasmids was detected by Western blot analysis.

Because of the importance of the carboxyl terminus (44) and higher conservation of the SDHD C-terminal tail compared with its N-terminal in Sdh4 and Shh4, we introduced a human SDHD C-terminal, including the G148D mutation, into yeast by creating the chimeras Sdh4-SDHD and Shh4-SDHD. Amino acids 146–160 of SDHD were swapped into equivalent positions in Sdh4 and Shh4. In sdh4Δ cells that expressed Shh4-SDHD, Sdh4-SDHD and Sdh4-SDHD G148D grew normally on glycerol. However, the chimera of human deficient proteins with Shh4 could not rescue the growth defect and the protein expression levels of these chimeras were also relatively lower than Sdh4-SDHD (Fig. 6B). These results indicate that compared with Sdh4, Shh4 is more suitable as a model for studying the role of SDHD in PGL.

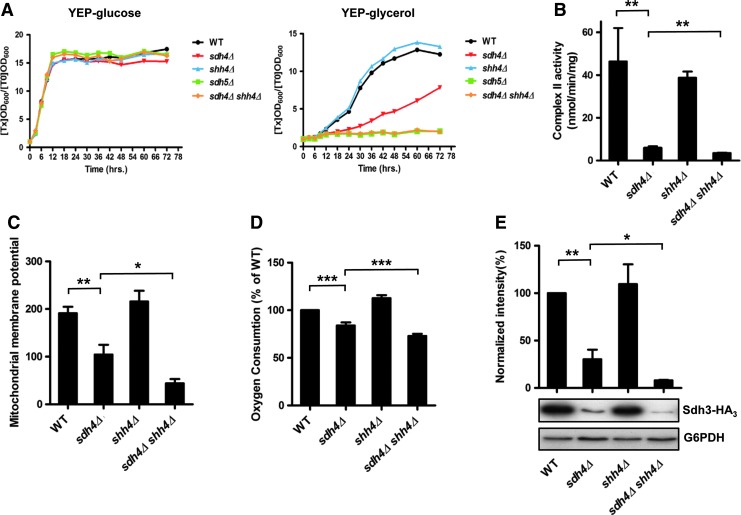

Although shh4Δ single mutant cells did not have a respiratory incompetent phenotype, deletion of SHH4 further augmented the deficient phenotype in sdh4Δ cells

Since Sdh4 and Shh4 variants cause protein instability and lower levels of protein in the cells, we used yeast deletion strains of these SDH complex subunits to further investigate the role of Shh4 in yeast mitochondrial SDH. We compared the growth curves of wild-type and mutants in YEP-glucose and YEP-glycerol media. No growth difference was observed between the single and double mutant strain under the fermentable carbon source, while a significant growth defect was observed in the sdh4Δ shh4Δ double mutant strain in the non-fermentable medium (Fig. 7A). However, cell growth was not affected in the shh4Δ null strain. The growth curve of the double mutant strain is similar to cells deleted in SDH5, a complex II assembly factor involved in the covalent attachment of FAD to Sdh1 (21), which does not have a paralog in yeast.

FIG. 7.

Although shh4Δ single mutant cells showed no respiratory incompetence phenotype, deletion of SHH4 further augmented the deficient phenotype in sdh4Δ cells. (A) Growth curves of indicated strains in YEP-glucose and YEP-glycerol media. The sdh4 shh4 double mutant stopped dividing in YEP-glycerol. (B) The SDH complex activity was analyzed using mitochondria isolated from wild-type and different yeast mutant strains. The enzyme activity was expressed as nmol/min/mg protein. (C) The mitochondria membrane potential was detected by FACS analysis after 30 min of DiOC6 staining. (D) The oxygen consumption rate was measured in cells grown in SC medium supplemented with 0.6% glucose. (E) The steady state of Sdh3 protein in the indicated deletion strains was detected using Western blot analysis. The values are given as mean±(n=3). *p value<0.05; **p value<0.01; and ***p value<0.001. DiOC6, 3,3′-dihexyloxacarbocyanine iodide; FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorting; SD, standard deviation. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

The complex II activity relies on the catalytic activity of Sdh1-Sdh2 dimer, but requires the intact Sdh3-Sdh4 assembly as well. To analyze the complex II activity, the succinate dependent, phenazine methosulfate-mediated dichlorophenolindophenol reductase activity was determined (23). The shh4 deletion showed no reduction in the complex II activity compared with wild type. The sdh4Δ caused a dramatically reduction, while loss of SHH4 in the sdh4Δ cells had slightly decreased complex II activity to sdh4Δ cells (Fig. 7B). Mitochondrial membrane potential is determined by a balance between electron transport chain-driven pumping of protons outward across the inner mitochondrial membrane and dissipation of the proton gradient (9), which is a signature of the integrity of mitochondria. We measured the mitochondrial membrane potential of wild-type YPH499, sdh4Δ, shh4Δ, and sdh4Δ shh4Δ strains by 3,3′-dihexyloxacarbocyanine iodide staining. The sdh4Δ strain had a lower mitochondrial membrane potential than the wild-type strain. Deletion of SHH4 in the sdh4Δ further decreased the mitochondrial membrane potential (Fig. 7C). The mitochondrion requires oxygen to produce sufficient ATP to drive energy requiring reactions in cells. We measured the mitochondrial oxygen consumption rate as a functional analysis of the mitochondria (6). The sdh4Δ strain had a lower oxygen consumption rate than the wild-type strain. Deletion of SHH4 in the sdh4Δ mutant further decreased the oxygen consumption rate (Fig. 7D). One explanation of the increased mitochondrial damage may be the disassembly of the SDH complex. In the SDH complex, Sdh3 and Sdh4 form a membrane-integrated heterodimer (36, 63). It has been reported that a lack of Sdh4 is associated with a large decrease in steady-state Sdh3, and this is due to the instability of Sdh3 (14, 45). We, therefore, examined whether the steady-state level of Sdh3, the catalytic partner in the Sdh3-Sdh4 heterodimer, was further disturbed in sdh4Δ shh4Δ null strains. Our results showed that the steady-state level of Sdh3 was reduced in the sdh4Δ shh4Δ mutant compared with the sdh4Δ mutant (Fig. 7E). However, the lack of Shh4 protein had no effect on mitochondrial membrane potential, O2 consumption, and steady-state Sdh3. These results suggest that Shh4 is a paralog of Sdh4 and the deletion of SHH4 in sdh4Δ cells further compromises respiratory competence, mitochondrial functions, and Sdh3 steady state.

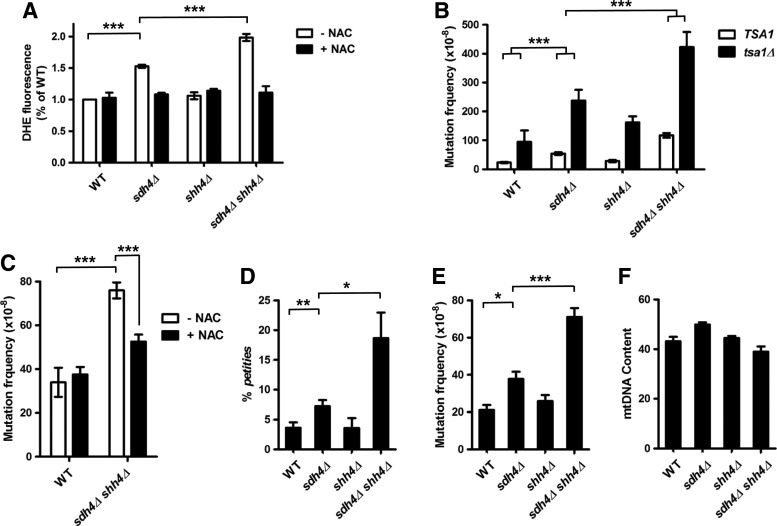

Deletion of SHH4 further increases ROS and nuclear genomic mutations in sdh4Δ cells

Since the mechanism of PGL tumorigenesis is not completely clear, we hypothesized that Sdh4 and Shh4 may induce the upregulation of ROS, which may contribute to the mutation phenotype. To examine this idea, we used the ROS-sensitive probe dihydroethidium (DHE) to measure intracellular ROS levels. The wild-type, sdh4Δ, shh4Δ, and sdh4Δ shh4Δ strains were grown to stationary phase and subjected to DHE staining. The sdh4Δ strain produced more ROS than the wild-type strain, and the deletion of SHH4 in sdh4Δ further increased intracellular ROS production (Fig. 8A). In contrast, treatment with the ROS scavenger N-acetyl-l-cysteine (NAC) completely abolished the increase in ROS in both sdh4Δ and sdh4Δ shh4Δ strains (Fig. 8A).

FIG. 8.

Deletion of SHH4 further increases ROS and enhances the nuclear DNA and mtDNA mutation frequency in sdh4 cells. (A) The intracellular levels of ROS generated in the indicated strains with and without NAC (20 mM, 48 h) were examined by DHE staining and FACS analysis. The DHE fluorescence value of each strain was normalized to the wild-type strain treated without NAC. The values are given as mean±SD (n=3). (B) Mutation frequencies to canavanine resistance were measured in strains with and without the TSA1 deletion. The number of canavanine resistant cells was normalized to the total viable numbers of cells. The values are given as mean±SD (n=6). (C) Mutation frequencies to canavanine resistance were measured in wild-type and sdh4Δ shh4Δ strains with and without NAC (5 mM). The number of canavanine-resistant cells was normalized to the total viable numbers of cells. The values are given as mean±SD (n=3). (D) The determination of petite frequency in wild-type, sdh4Δ, shh4Δ, and sdh4Δ shh4Δ strains. More than 4000 colonies per strain were scored. For each strain, the values are given as mean±SD (n=3). (E) The frequency of erythromycin-resistant mutants in wild-type, sdh4Δ, shh4Δ, and sdh4Δ shh4Δ strains was measured. The number of erythromycin-resistant cells was normalized to the total viable number of cells on YEP-glycerol plates. The values are given as mean±SD (n=3). (F) The relative mtDNA content of wild-type, sdh4Δ, shh4Δ, and sdh4Δ shh4Δ strains was measured by real-time polymerase chain reaction (measured as the ratio of the mitochondrial gene target COX1 relative to the nuclear gene target ACT1). *p value<0.05; **p value<0.01; ***p value<0.001. DHE, dihydroethidium; NAC, N-acetyl-l-cysteine; ROS, reactive oxygen species.

To investigate whether the production of ROS contributes to the mutant phenotype, the frequencies of forward mutations to canavanine resistance were determined in sdh4 and shh4 sdh4 cells. Surprisingly, in the sdh4Δ shh4Δ cells, the mutation frequency was dramatically elevated (Fig. 8B). This elevation was abolished by treatment with the antioxidant NAC. However, NAC treatment had no significant effect on the mutation phenotype in the wild-type strain (Fig. 8C). Moreover, yeast TSA1 encodes thioredoxin peroxidase, which acts as a cytoplasmic antioxidant and a scavenger of ROS (13). Deletion of TSA1 further increased the mutation frequencies in these strains (Fig. 8B). In addition to sdh4, shh4, and sdh4 shh4 cells, the production of ROS and the mutagenesis phenotype was observed in the other sdh mutants (sdh1Δ, sdh2Δ, and sdh3Δ). The ROS production and mutagenesis phenotype were the highest in sdh2Δ null cells among the other complex II subunits. Furthermore, sdh3Δ cells produce almost an equal amount of ROS and bear a similar mutagenesis phenotype with sdh4Δ cells (Supplementary Fig. S4A, B). These results indicate that the deficiency of Sdh4 and Shh4 may result in an extensive production of ROS which contributes to an increase in mutation frequency and genomic instability (Supplementary Fig. S4C).

The ROS produced in sdh4Δ and sdh4Δ shh4Δ null cells contribute to aberrant mtDNA

The mitochondrion is the largest intracellular source of ROS in aerobic cells. Increasing ROS production in the mitochondria is predicted to increase the susceptibility of mtDNA to oxidative damage, resulting in the accumulation of aberrant mtDNA. The spontaneous formation of yeast petite mutants is a measure of mtDNA integrity (57). These petite mutants have lost respiratory competence and do not grow on non-fermentable carbon sources. To evaluate the effect of wild-type, sdh4Δ, shh4Δ, and sdh4Δ shh4Δ on mtDNA instability, these deleted strains were cultured in YEP-glycerol to counterselect petite cells. The petite frequency was slightly increased in sdh4Δ cells, and dramatically increased in sdh4Δ shh4Δ cells (Fig. 8D).

Next, the fidelity of mtDNA replication was estimated by the resistance frequency to erythromycin (EryR) (10). The resistance to Ery is caused by specific point mutations in mtDNA-encoded rRNA genes (62). Using this assay, we measured the mtDNA mutagenesis in sdh4Δ and shh4Δ single mutant strains and in the corresponding double mutant. Similar to the petite frequency, the mtDNA mutagenesis was slightly increased in sdh4Δ cells (∼1.8-fold), and further increased in sdh4Δ shh4Δ cells (∼3.4-fold) (Fig. 8E), indicating that loss of both Sdh4 and Shh4 has a greater effect on mtDNA mutagenesis.

Increasing ROS production is associated with the accumulation of aberrant mtDNA. In order to maintain mtDNA integrity, the damaged mtDNA is degraded and lost in response to oxidative stress (12, 58). Compared with the wild-type and shh4Δ strains, sdh4Δ and sdh4Δ shh4Δ strains produce more ROS and contain more damaged mtDNA. However, the quantification of mtDNA content showed no difference between these strains (Fig. 8F). These data, along with the assessment of ROS production levels, suggest that deficient SDH complex-mediated oxidative stress directly contributes to petite formation, mtDNA mutagenesis, but not loss of mtDNA.

The sdh4Δ and sdh4Δ shh4Δ mutants have a shorter chronological lifespan

Mitochondria are involved in aging and age-related pathology (3). The Mitochondrial Free Radical Theory of Aging (MFRTA) is one of the most influential theories of aging (22). The MFRTA is supported by the accumulation of oxidative damage during aging, and predicts that long‐lived individuals or species produce fewer mtROS; a decrease in mtROS production will increase lifespan; and an increase in mtROS production will decrease lifespan. According to the MFRTA, we speculated that the chronological lifespan (CLS), the survival time of yeast cells in a non-dividing population in post-diauxic and stationary-phase cultures, might decrease in SDH complex null cells. To address this hypothesis, we analyzed cell viability after the cells entered the stationary phase. It was observed that the lifespan of the sdh4Δ and sdh4Δ shh4Δ mutants was reduced compared with the wild-type yeast at day 7. Deletion of SHH4 in sdh4Δ further abolished the lifespan extension after day 11 (Fig 9). Our results suggest that yeast longevity is decreased in sdh4Δ and sdh4Δ shh4Δ, but not in the shh4Δ null strain.

FIG. 9.

The sdh4Δ and sdh4Δ shh4Δ mutants have a shorter chronological lifespan. Wild-type, sdh4Δ, shh4Δ, and sdh4Δ shh4Δ strains were grown in SC-glucose medium and supplemented with a four-fold excess of tryptophan, leucine, uracil, lysine, adenine, and histidine. Viability at day 3, when the yeast had reached stationary phase, was defined as initial survival. From day 7, the same cell numbers from the culture were diluted 10-fold and spotted on YEP-glucose plates every 2 days. The rim15Δ serves as a control for decreased lifespan, and the sch9Δ serves as a control for extended lifespan.

Discussion

PGL is a rare and mostly benign tumor. The SDHD mutation is the most common form of familial PGL, classified as PGL1, and accounts for approximately 30% of hereditary PGL (7). The transmission pattern of SDHD mutations shows parent-of-origin-dependent penetrance. The PGL1 disease phenotype is transmitted only through the father, suggesting a maternal genomic imprinting of SDHD (24, 39, 42). However, the underlying mechanism of maternal imprinting and the precise pathway leading from the SDHD mutation to tumorigenesis is unclear.

Shh4 is a functionally redundant SDHD paralog in yeast

In yeast, the functional homolog of SDHD was previously assigned to Sdh4. However, we revealed that another conserved homolog, Shh4, might shed light on the role of SDHD in PGL. In recent studies, Shh4 was found to interact with Sdh3. Deletion of SHH4, however, affected neither yeast growth nor the blue native mobility of SDH complex (14). In addition, Szeto et al. found that Shh4 can form a respiration-competent SDH isoenzyme with Sdh3 (64). Since the sequence alignment of Shh4 displays a higher similarity to SDHD than Sdh4, we first investigated the role of Shh4 in complex II. Our data revealed that when cells were cultured in YEP-glycerol, the sdh4 shh4 double mutant had a stronger growth defect than the sdh4Δ strain (Figs. 4C and 7A). These findings suggested a redundant function of Shh4 in complex II. Mitochondrial membrane potential is supported by the integrity of the mitochondrial membrane and is used to characterize cellular metabolism, viability, and apoptosis (9). The mitochondrion requires oxygen to produce sufficient ATP to drive energy-required reactions in cells. The mitochondrial oxygen consumption rate is another indicator of mitochondrial function (6). We observed that the mitochondrial SDH complex activity, the membrane potential, and the oxygen consumption rate of the sdh4Δ shh4Δ cells are lower than in sdh4Δ cells (Fig. 7B–D). In addition, the deletion of SHH4 in sdh4Δ cells further compromises the steady state of Sdh3 (Fig. 7E). Moreover, in the SDH4 deletion strain, Shh4 expression is induced and expression of Shh4 complements the growth defect of the SDH4 deletion in a non-fermentable carbon source (Fig. 5A, B). These data support Shh4 as a functionally redundant protein for its SDH D ortholog Sdh4 in yeast.

Whole-genome duplication allows cells to overcome environmental stress

Genetically, evolution occurs by gene mutation and selection. Whole-genome duplication has been proposed as an advantageous strategy in evolution (31, 48), because a duplicated gene may provide a better chance in response to pressure-mediated selection. The adaptation depends on the endurance to environmental stress. For example, Shh4, but not Sdh4, is overexpressed under several types of stress; thus, the gene redundancy of SDH4 and SHH4 perhaps provides an advantage for yeast to overcome environmental stress. The expression of SDHD was also induced under different dosages of H2O2 in HUVECs (Supplementary Fig. S1C). The responses of Shh4 and SDHD to stress might explain why yeast Shh4 has a closer genetic distance to human SDHD. The similarities between SDHD and Shh4 may be the result of either convergent evolution or loss of features in the Sdh4 paralogue.

Yeast Shh4/Sdh4 deficiency-mediated ROS production and nuclear and mitochondrial genomic mutations may contribute to aging and imply that similar processes may be at play in the role of SDHD for tumorigenesis

Previous studies cannot clearly explain the mechanism of SDHD mutation-mediated PGL formation. There are four hypotheses predicting how deficient SDH may generate PGL (Fig. 10). Our results revealed that cellular ROS in the sdh4Δ shh4Δ strain was higher than in the sdh4Δ strain (Fig. 8A). Correlatively, the mutation frequency of the sdh4Δ shh4Δ cells is higher than in the sdh4 cells. More importantly, the mutation frequencies were further increased in tsa1Δ (Fig. 8B) and an ROS scavenger (NAC) could rescue this damage (Fig. 8C). A previous study provided evidence for SDHB-linked ROS production and mitochondrial damage in the yeast model (17). In our results, the sdh4Δ shh4Δ strain showed lower mtDNA integrity and higher mtDNA mutability (Fig. 8D, E). Other studies also support a link between mtDNA mutation and tumorigenesis (11, 49). Extrapolated to the mammalian system, our results suggest that the ROS generated from the SDHD defect increases nuclear and mitochondrial mutation frequency and contributes to tumorigenesis. Moreover, ROS generated from the respiratory chain has been suggested to be a major source for aging, and ROS homeostasis plays an important role in chronological aging processes (16). Our results showed that sdh4Δ shh4Δ strain further leads to a reduction in CLS (Fig. 9), which may be also due to the ROS-mediated mutagenesis.

FIG. 10.

Four proposed models link SDH deficiencies and PGL tumorigenesis. The first model proposes that ROS is a signal molecule promoting tumor formation in SDH-deficient cells by inhibiting HIFα PHD activity. The second model predicts that the defects in SDH result in an increase in ROS, and the resultant oxidative damage to mitochondrial and nuclear DNA leads to tumorigenesis. The third model suggests that the defects in SDH lead to succinate accumulation and induce a pseudo-hypoxic response which promotes the stabilization of HIFα. The fourth model surmises that mutated SDH triggers succinate accumulation, inhibits DNA demethylase, and prevents the expression of some tumor suppressor genes. HIFα, hypoxia-inducible factor α; PHDs, prolyl hydroxylases. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to theweb version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

We investigated deficiency of each complex II subunit and found that sdh2Δ produced more ROS and caused higher nuclear DNA mutation than other subunit deletion (Supplementary Fig. S4A, B). The Sdh1–Sdh2 complex couples the oxidation of succinate and transfers electrons to ubiquinone. Its defect easily causes electron leakage-mediated ROS production. It is well known that SDHB-associated pheochromocytoma/PGL often leads to metastasis. Previous studies showed that increasing ROS was detected in response to the suppression of SDHB expression (19). In yeast, most of mitochondrial complex II subunits have genome duplication products except SDH2. Our results showed that it requires the deletion of SHH4 to further increase the ROS production in sdh4Δ null cells, implying that loss of SDH2 alone might cause more severe oxidative stress.

Shh4 may be a better research model than Sdh4 to study SDHD defect-mediated tumorigenesis in PGL

How the mutated SDHD subunit would lead a compromised function of the SDH complex was another mystery. All six clinical carotid body tumor samples from familial PGLs showed weak or no staining of SDHD, and 16 out of 21 clinical carotid body tumor samples from sporadic PGLs displayed weak-to-moderate staining of SDHD (Fig. 1A). A study in human 293T cells showed that protein stability was lower in SDHD than in wild-type SDHD, and that the loss of protein stability was caused by an increase in degradation through the proteasome (Fig. 1B, C). The proteasome is a cytosolic protein degradation system. This proteolytic pathway is mostly mediated by the recognition of polyubiquitin chains on the protein targets. However, the cytosolic proteasomal pathway to degrade intramitochondrial proteins has recently been identified (1,2). The SDHB subunit of the mitochondrial SDH complex was also shown to be ubiquitinated and degraded by the cytosolic proteasome (70). Consistent with this idea, our result revealed that the reduced expression of mutant SDHDs was through proteasomal ubiquitin-mediated degradation (Fig. 1C). A striking finding in this study is that the protein expression levels of many disease-mimicking Sdh4 and Shh4 mutants are decreased. In addition, the shh4 point mutants have a more severe growth defect and the mutated Shh4 proteins are less stable than the mutated Sdh4 proteins (Fig. 6A). Another important discovery was that when the hybrid forms of human SDHD were expressed in yeast, the strain with the hybrid in Shh4 exhibited a growth defect on SC-glycerol plates. However, this phenotype was not duplicated in strains with the hybrid in Sdh4 (Fig. 6B). SDHD G148D is one of the missense mutations identified in PGL patients, and its corresponding mutation in Sdh4 (sdh4 G157D) showed only little decreased in protein level, but an obvious reduction in Shh4 (shh4 G149D). The G157 residue is located on the Sdh4 carboxyl terminus, which is necessary for respiration on non-fermentable carbon sources, for quinone reduction, and for enzyme stability (44). In our results, only SDHD G148D corresponding mutation generated in Shh4 and Shh4-SDHD chimera could cause a severe decrease in protein expression and a deficiency in respiratory competence, but not in Sdh4 and Sdh4-SDHD chimera (Fig. 6A, B). This result might imply that the folding of the carboxyl terminus of SDHD is more similar to that of the Shh4. Although previous research supports Sdh4 as a model to study the mechanism of PGL formation (46), based on our findings, we suggest that Shh4 is a better research model than Sdh4 to mimic the SDHD defect in PGL.

Materials and Methods

Yeast strains and media

Saccharomyces cerevisiae YPH499 was used as the parental and wild-type strain. Deletion mutants in YPH499 were generated by double cross-over of the wild-type gene locus with the KanMX4 fragment amplified from a yeast deletion library (Invitrogen). The tagged strains were created by integration of the Myc9 or HA3 tag in-frame downstream of specific genes in the genome of YPH499. The yeast media used were rich medium (YEP, 1% yeast extract, 2% peptone) or SC medium containing either 2% glucose or 3% glycerol, as indicated. Nitrogen starvation was performed as previously described (25). For deficient and chimera protein expression, the sdh4Δ yeast mutant strain was transformed with a high copy YEPFAT7 plasmid (52) carrying the wild-type SDH4 and SHH4, the conserved human PGL disease mutant alleles (4), chimera wild-type SDH4-SDHD and SHH4-SDHD, and chimera SDH4-SDHD and SHH4-SDHD carrying the human PGL disease mutant G148D or the empty vector. The chimera DNAs were amplified by an overlapping polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and were cloned into the multiple cloning sites of YEPFAT7. All yeast strains, primer sequences, and constructs used in this study are mentioned in Supplementary Tables S1–S3.

Construction of yeast mutant alleles and chimeric genes

To obtain pYEPFAT7-SDH4 and pYEPFAT7-SHH4 plasmids, the SDH4 and SHH4 DNA fragment containing ORF and the 5′ and 3′ flanking regions were amplified by PCR using SDH4-HA3 and SHH4-HA3 genomic DNA as a template and oligos contained appropriate restriction enzyme sites as primers. The amplified SDH4 and SHH4 PCR fragments were digested by SmaI and SphI or XhoI and SphI, respectively; and were cloned into pYEPFAT7. The sdh4 and shh4 mutant allele, which are the correspondents of human SDHD pathogenic variants, were produced by site-directed mutagenesis using HiFi polymerase (Kapa Biosystems). The fragment of SDH4 promoter was amplified by PCR and digested with SmaI and HindIII to clone into pYEPFAT7. The chimeric constructs are driven by SDH4 promoter. The SDH4 and Shh4 fragments of chimeric genes were amplified by PCR using yeast genomic DNA as a template, and the SDHD fragment of chimeric genes was amplified by using pGEMT-easy-SDHD-HA3 as a template. The PCR amplified fragments of SDH4 and SHH4 were digested by SmaI and ClaI, while the SDHD PCR fragment was cut by ClaI and SphI. These fragments were cloned into pYEPFAT7.

Analysis of ROS production

Cells were cultured for 48 h and washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Next, 1×107 cells were resuspended in 100 μl PBS and DHE (Molecular Probes) was added to a final concentration of 50 μM. The cell suspension was incubated for 10 min in the dark and washed with PBS. The stained cells were diluted to 1×106 cells/ml and analyzed by flow cytometry using the FL3 channel without compensation.

Measurement of mutation frequency

The assay for mutation frequency was conducted as previously described, with some modifications (38). The cells were diluted to ∼1000 cells/ml in at least six separate cultures and grown to 1–3×107 cells/ml in YEP-glycerol. Diluted cells were plated onto SC-glucose medium containing l-canavanine (60 μg/ml; Sigma) and lacking arginine to identify forward mutations in the CAN1 gene, and onto SC-glucose medium lacking arginine for viable cell numbers. The mutation frequency was determined as the number of canavanine-resistant cells normalized to the total viable cell number.

PGL clinical samples and IHC

Carotid body tumor specimens were obtained from six patients with familial PGLs and 21 patients with sporadic PGLs who underwent surgery at the Department of Otolaryngology of the National Taiwan University Hospital. Ethics approvals for human studies were obtained from the Institutional Review Board of the National Taiwan University Hospital, and informed consent was provided by each patient. IHC was detected as previously described (67) using an antibody against SDHD (Novus Biologicals). The percentage of positive cells and intensity was analyzed in three different fields in each tissue. For the assessment of intensity, each field was graded semi-quantitatively on a scale, where 0=no staining, 1=weak staining, 2=moderate staining, and 3=strong staining.

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations Used

- CCCP

carbonyl cyanide 3-chlorophenylhydrazone

- Cd

cadmium

- CHX

cycloheximide

- CLS

chronological lifespan

- DHE

dihydroethidium

- DiOC6

3,3′-dihexyloxacarbocyanine iodide

- Ery

erythromycin

- EV

empty vector

- FACS

fluorescence-activated cell sorting

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- G6PDH

glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase

- H2O2

hydrogen peroxide

- HIFα

hypoxia-inducible factor α

- HUVEC

human umbilical vein endothelial cell

- IHC

immunohistochemistry

- MFRTA

The Mitochondrial Free Radical Theory of Aging

- MMS

methyl methanesulfonate

- NAC

N-acetyl-l-cysteine

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- PGL

paraganglioma

- EDTA

ethylenedimainetetraaceticacid

- PHDs

prolyl hydroxylases

- pVHL

von Hippel-Lindau

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SC

synthetic complete

- SD

standard deviation

- SDH

succinate dehydrogenase

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs. Jing-Jer Lin and Tsai-Kun Li for valuable inputs. They also thank Drs. Chen-Tu Wu and Yih-Leong Chang for paraffin slides preparation and pathology review, Dr. Yau-Huei Wei for the help of several mitochondria-related assays, Dr. Che-Ming Teng for providing HUVEC, and Dr. Fang-Jen Lee for providing Porin and Kar2 antibodies. This work was supported by grants from the National Science Council (NRPGM-100-3112-B-002-039 to S.-C.T.) and (NSC-102-2314-B-002-106 to P.-J.L.); the National Taiwan University (NTU CESRP-101R7602A1 to S.-C.T.); the National Health Research Institute (NHRI-EX98-9727BI to S.-C.T.); and the Academia Sinica (TWN HNC Biosignature to P.-J.L.).

Author Disclosure Statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Azzu V. and Brand MD. Degradation of an intramitochondrial protein by the cytosolic proteasome. J Cell Sci 123: 578–585, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Azzu V, Mookerjee SA, Brand MD. Rapid turnover of mitochondrial uncoupling protein 3. Biochem J 426: 13–17, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balaban RS, Nemoto S, and Finkel T. Mitochondria, oxidants, and aging. Cell 120: 483–495, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bayley JP, Devilee P, and Taschner PE. The SDH mutation database: an online resource for succinate dehydrogenase sequence variants involved in pheochromocytoma, paraganglioma and mitochondrial complex II deficiency. BMC Med Genet 6: 39, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baysal BE. Hereditary paraganglioma targets diverse paraganglia. J Med Genet 39: 617–622, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brand MD. and Nicholls DG. Assessing mitochondrial dysfunction in cells. Biochem J 435: 297–312, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buffet A, Venisse A, Nau V, Roncellin I, Boccio V, Le Pottier N, Boussion M, Travers C, Simian C, Burnichon N, Abermil N, Favier J, Jeunemaitre X, and Gimenez-Roqueplo AP. A decade (2001–2010) of genetic testing for pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Horm Metab Res 44: 359–366, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burnichon N, Rohmer V, Amar L, Herman P, Leboulleux S, Darrouzet V, Niccoli P, Gaillard D, Chabrier G, Chabolle F, Coupier I, Thieblot P, Lecomte P, Bertherat J, Wion-Barbot N, Murat A, Venisse A, Plouin PF, Jeunemaitre X, and Gimenez-Roqueplo AP. The succinate dehydrogenase genetic testing in a large prospective series of patients with paragangliomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 94: 2817–2827, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen LB. Mitochondrial membrane potential in living cells. Annu Rev Cell Biol 4: 155–181, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chi NW. and Kolodner RD. Purification and characterization of Msh1, a yeast mitochondrial protein that binds to DNA mismatches. J Biol Chem 269: 29984–29992, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fliss MS, Usadel H, Caballero OL, Wu L, Buta MR, Eleff SM, Jen J, and Sidransky D. Facile detection of mitochondrial DNA mutations in tumors and bodily fluids. Science 287: 2017–2019, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Furda AM, Marrangoni AM, Lokshin A, and Van Houten B. Oxidants and not alkylating agents induce rapid mtDNA loss and mitochondrial dysfunction. DNA Repair (Amst) 11: 684–692, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garrido EO. and Grant CM. Role of thioredoxins in the response of Saccharomyces cerevisiae to oxidative stress induced by hydroperoxides. Mol Microbiol 43: 993–1003, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gebert N, Gebert M, Oeljeklaus S, von der Malsburg K, Stroud DA, Kulawiak B, Wirth C, Zahedi RP, Dolezal P, Wiese S, Simon O, Schulze-Specking A, Truscott KN, Sickmann A, Rehling P, Guiard B, Hunte C, Warscheid B, van der Laan M, Pfanner N, and Wiedemann N. Dual function of Sdh3 in the respiratory chain and TIM22 protein translocase of the mitochondrial inner membrane. Mol Cell 44: 811–818, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gerald D, Berra E, Frapart YM, Chan DA, Giaccia AJ, Mansuy D, Pouyssegur J, Yaniv M, and Mechta-Grigoriou F. JunD reduces tumor angiogenesis by protecting cells from oxidative stress. Cell 118: 781–794, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giorgio M, Trinei M, Migliaccio E, and Pelicci PG. Hydrogen peroxide: a metabolic by-product or a common mediator of ageing signals? Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 8: 722–728, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goffrini P, Ercolino T, Panizza E, Giache V, Cavone L, Chiarugi A, Dima V, Ferrero I, and Mannelli M. Functional study in a yeast model of a novel succinate dehydrogenase subunit B gene germline missense mutation (C191Y) diagnosed in a patient affected by a glomus tumor. Hum Mol Genet 18: 1860–1868, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guzy RD. and Schumacker PT. Oxygen sensing by mitochondria at complex III: the paradox of increased reactive oxygen species during hypoxia. Exp Physiol 91: 807–819, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guzy RD, Sharma B, Bell E, Chandel NS, and Schumacker PT. Loss of the SdhB, but Not the SdhA, subunit of complex II triggers reactive oxygen species-dependent hypoxia-inducible factor activation and tumorigenesis. Mol Cell Biol 28: 718–731, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hagen T. Oxygen versus reactive oxygen in the regulation of HIF-1alpha: the balance tips. Biochem Res Int 2012: 436981, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hao HX, Khalimonchuk O, Schraders M, Dephoure N, Bayley JP, Kunst H, Devilee P, Cremers CW, Schiffman JD, Bentz BG, Gygi SP, Winge DR, Kremer H, and Rutter J. SDH5, a gene required for flavination of succinate dehydrogenase, is mutated in paraganglioma. Science 325: 1139–1142, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harman D. Aging: a theory based on free radical and radiation chemistry. J Gerontol 11: 298–300, 1956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haslam JM, Perkins M, and Linnane AW. Biogenesis of mitochondria. A requirement for mitochondrial protein synthesis for the formation of a normal adenine nucleotide transporter in yeast mitochondria. Biochem J 134: 935–947, 1973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heutink P, van der Mey AG, Sandkuijl LA, van Gils AP, Bardoel A, Breedveld GJ, van Vliet M, van Ommen GJ, Cornelisse CJ, Oostra BA, et al. A gene subject to genomic imprinting and responsible for hereditary paragangliomas maps to chromosome 11q23-qter. Hum Mol Genet 1: 7–10, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang YC, Chen HT, and Teng SC. Intragenic transcription of a noncoding RNA modulates expression of ASP3 in budding yeast. RNA 16: 2085–2093, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ishii T, Yasuda K, Akatsuka A, Hino O, Hartman PS, and Ishii N. A mutation in the SDHC gene of complex II increases oxidative stress, resulting in apoptosis and tumorigenesis. Cancer Res 65: 203–209, 2005 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ivan M, Kondo K, Yang H, Kim W, Valiando J, Ohh M, Salic A, Asara JM, Lane WS, and Kaelin WG., Jr.HIFalpha targeted for VHL-mediated destruction by proline hydroxylation: implications for O2 sensing. Science 292: 464–468, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jelinsky SA. and Samson LD. Global response of Saccharomyces cerevisiae to an alkylating agent. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96: 1486–1491, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Josse L, Li X, Coker RD, Gourlay CW, and Evans IH. Transcriptomic and phenotypic analysis of the effects of T-2 toxin on Saccharomyces cerevisiae: evidence of mitochondrial involvement. FEMS Yeast Res 11: 133–150, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaelin WG, Jr., and Ratcliffe PJ. Oxygen sensing by metazoans: the central role of the HIF hydroxylase pathway. Mol Cell 30: 393–402, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kellis M, Birren BW, and Lander ES. Proof and evolutionary analysis of ancient genome duplication in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature 428: 617–624, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kerscher O, Sepuri NB, and Jensen RE. Tim18p is a new component of the Tim54p-Tim22p translocon in the mitochondrial inner membrane. Mol Biol Cell 11: 103–116, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Killian JK, Kim SY, Miettinen M, Smith C, Merino M, Tsokos M, Quezado M, Smith WI, Jr., Jahromi MS, Xekouki P, Szarek E, Walker RL, Lasota J, Raffeld M, Klotzle B, Wang Z, Jones L, Zhu Y, Wang Y, Waterfall JJ, O'Sullivan MJ, Bibikova M, Pacak K, Stratakis C, Janeway KA, Schiffman JD, Fan JB, Helman L, and Meltzer PS. Succinate dehydrogenase mutation underlies global epigenomic divergence in gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Cancer Discov 3: 648–657, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kresnowati MTAP, van Winden WA, Almering MJH, ten Pierick A, Ras C, Knijnenburg TA, Daran-Lapujade P, Pronk JT, Heijnen JJ, and Daran JM. When transcriptome meets metabolome: fast cellular responses of yeast to sudden relief of glucose limitation. Mol Syst Biol 2: 49, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee JH, Barich F, Karnell LH, Robinson RA, Zhen WK, Gantz BJ, and Hoffman HT. National Cancer Data Base report on malignant paragangliomas of the head and neck. Cancer 94: 730–737, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lemire BD. and Oyedotun KS. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae mitochondrial succinate:ubiquinone oxidoreductase. Biochim Biophys Acta 1553: 102–116, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Letouze E, Martinelli C, Loriot C, Burnichon N, Abermil N, Ottolenghi C, Janin M, Menara M, Nguyen AT, Benit P, Buffet A, Marcaillou C, Bertherat J, Amar L, Rustin P, De Reynies A, Gimenez-Roqueplo AP, and Favier J. SDH mutations establish a hypermethylator phenotype in paraganglioma. Cancer Cell 23: 739–752, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lin YH, Chang CC, Wong CW, and Teng SC. Recruitment of Rad51 and Rad52 to short telomeres triggers a Mec1-mediated hypersensitivity to double-stranded DNA breaks in senescent budding yeast. PLoS One 4: e8224, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mariman EC, van Beersum SE, Cremers CW, Struycken PM, and Ropers HH. Fine mapping of a putatively imprinted gene for familial non-chromaffin paragangliomas to chromosome 11q13.1: evidence for genetic heterogeneity. Hum Genet 95: 56–62, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maxwell PH, Wiesener MS, Chang GW, Clifford SC, Vaux EC, Cockman ME, Wykoff CC, Pugh CW, Maher ER, and Ratcliffe PJ. The tumour suppressor protein VHL targets hypoxia-inducible factors for oxygen-dependent proteolysis. Nature 399: 271–275, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Momose Y. and Iwahashi H. Bioassay of cadmium using a DNA microarray: genome-wide expression patterns of Saccharomyces cerevisiae response to cadmium. Environ Toxicol Chem 20: 2353–2360, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Muller U. Pathological mechanisms and parent-of-origin effects in hereditary paraganglioma/pheochromocytoma (PGL/PCC). Neurogenetics 12: 175–181, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Owens KM, Aykin-Burns N, Dayal D, Coleman MC, Domann FE, and Spitz DR. Genomic instability induced by mutant succinate dehydrogenase subunit D (SDHD) is mediated by O2(−*) and H2O2. Free Radic Biol Med 52: 160–166, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oyedotun KS. and Lemire BD. The carboxyl terminus of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae succinate dehydrogenase membrane subunit, SDH4p, is necessary for ubiquinone reduction and enzyme stability. J Biol Chem 272: 31382–31388, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Oyedotun KS. and Lemire BD. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae succinate-ubiquinone reductase contains a stoichiometric amount of cytochrome b562. FEBS Lett 442: 203–207, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Panizza E, Ercolino T, Mori L, Rapizzi E, Castellano M, Opocher G, Ferrero I, Neumann HP, Mannelli M, and Goffrini P. Yeast model for evaluating the pathogenic significance of SDHB, SDHC and SDHD mutations in PHEO-PGL syndrome. Hum Mol Genet 22: 804–815, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pellitteri PK, Rinaldo A, Myssiorek D, Gary Jackson C, Bradley PJ, Devaney KO, Shaha AR, Netterville JL, Manni JJ, and Ferlito A. Paragangliomas of the head and neck. Oral Oncol 40: 563–575, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Piskur J. and Langkjaer RB. Yeast genome sequencing: the power of comparative genomics. Mol Microbiol 53: 381–389, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Polyak K, Li Y, Zhu H, Lengauer C, Willson JK, Markowitz SD, Trush MA, Kinzler KW, and Vogelstein B. Somatic mutations of the mitochondrial genome in human colorectal tumours. Nat Genet 20: 291–293, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Quinlan CL, Orr AL, Perevoshchikova IV, Treberg JR, Ackrell BA, and Brand MD. Mitochondrial complex II can generate reactive oxygen species at high rates in both the forward and reverse reactions. J Biol Chem 287: 27255–27262, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rintala E, Toivari M, Pitkanen JP, Wiebe MG, Ruohonen L, and Penttila M. Low oxygen levels as a trigger for enhancement of respiratory metabolism in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. BMC Genomics 10: 461, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Runge KW. and Zakian VA. Introduction of extra telomeric DNA sequences into Saccharomyces cerevisiae results in telomere elongation. Mol Cell Biol 9: 1488–1497, 1989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rutter J, Winge DR, and Schiffman JD. Succinate dehydrogenase—assembly, regulation and role in human disease. Mitochondrion 10: 393–401, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Scherens B, Feller A, Vierendeels F, Messenguy F, and Dubois E. Identification of direct and indirect targets of the Gln3 and Gat1 activators by transcriptional profiling in response to nitrogen availability in the short and long term. FEMS Yeast Res 6: 777–791, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schipper J, Boedeker CC, Maier W, and Neumann HP. [Paragangliomas in the head-/neck region. I: Classification and diagnosis]. HNO 52: 569–574; quiz 575, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Selak MA, Armour SM, MacKenzie ED, Boulahbel H, Watson DG, Mansfield KD, Pan Y, Simon MC, Thompson CB, and Gottlieb E. Succinate links TCA cycle dysfunction to oncogenesis by inhibiting HIF-alpha prolyl hydroxylase. Cancer Cell 7: 77–85, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shadel GS. Yeast as a model for human mtDNA replication. Am J Hum Genet 65: 1230–1237, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shokolenko I, Venediktova N, Bochkareva A, Wilson GL, and Alexeyev MF. Oxidative stress induces degradation of mitochondrial DNA. Nucleic Acids Res 37: 2539–2548, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sickmann A, Reinders J, Wagner Y, Joppich C, Zahedi R, Meyer HE, Schonfisch B, Perschil I, Chacinska A, Guiard B, Rehling P, Pfanner N, and Meisinger C. The proteome of Saccharomyces cerevisiae mitochondria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100: 13207–13212, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Silkin Y, Oyedotun KS, and Lemire BD. The role of Sdh4p Tyr-89 in ubiquinone reduction by the Saccharomyces cerevisiae succinate dehydrogenase. Biochim Biophys Acta 1767: 143–150, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Slane BG, Aykin-Burns N, Smith BJ, Kalen AL, Goswami PC, Domann FE, and Spitz DR. Mutation of succinate dehydrogenase subunit C results in increased O2−, oxidative stress, and genomic instability. Cancer Res 66: 7615–7620, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sor F. and Fukuhara H. Erythromycin and spiramycin resistance mutations of yeast mitochondria—nature of the Rib2 locus in the large ribosomal-Rna gene. Nucleic Acids Res 12: 8313–8318, 1984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sun F, Huo X, Zhai Y, Wang A, Xu J, Su D, Bartlam M, and Rao Z. Crystal structure of mitochondrial respiratory membrane protein complex II. Cell 121: 1043–1057, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Szeto SS, Reinke SN, Oyedotun KS, Sykes BD, and Lemire BD. Expression of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Sdh3p and Sdh4p paralogs results in catalytically active succinate dehydrogenase isoenzymes. J Biol Chem 287: 22509–22520, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Timmers HJ, Pacak K, Bertherat J, Lenders JW, Duet M, Eisenhofer G, Stratakis CA, Niccoli-Sire P, Tran BH, Burnichon N, and Gimenez-Roqueplo AP. Mutations associated with succinate dehydrogenase D-related malignant paragangliomas. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 68: 561–566, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Walker DW, Hajek P, Muffat J, Knoepfle D, Cornelison S, Attardi G, and Benzer S. Hypersensitivity to oxygen and shortened lifespan in a Drosophila mitochondrial complex II mutant. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103: 16382–16387, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wang CP, Chen TC, Chang YL, Ko JY, Yang TL, Lo FY, Hu YL, Chen PL, Wu CC, and Lou PJ. Common genetic mutations in the start codon of the SDH subunit D gene among Chinese families with familial head and neck paragangliomas. Oral Oncol 48: 125–129, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Xiao M, Yang H, Xu W, Ma S, Lin H, Zhu H, Liu L, Liu Y, Yang C, Xu Y, Zhao S, Ye D, Xiong Y, and Guan KL. Inhibition of alpha-KG-dependent histone and DNA demethylases by fumarate and succinate that are accumulated in mutations of FH and SDH tumor suppressors. Genes Dev 26: 1326–1338, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Xu J, Maki D, and Stapleton SR. Mediation of cadmium-induced oxidative damage and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase expression through glutathione depletion. J Biochem Mol Toxicol 17: 67–75, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yang C, Matro JC, Huntoon KM, Ye DY, Huynh TT, Fliedner SM, Breza J, Zhuang Z, and Pacak K. Missense mutations in the human SDHB gene increase protein degradation without altering intrinsic enzymatic function. FASEB J 26: 4506–4516, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.