Abstract

Background

Myocardial scars harbor areas of slow conduction and display abnormal electrograms. Pace-mapping at these sites can generate a 12-lead electrocardiogram morphological match to a targeted ventricular tachycardia (VT), and in some instances, multiple exit morphologies can result. At times, this can also result in the initiation of VT, termed pace-mapped induction (PMI). We hypothesized that in patients undergoing catheter ablation of VT, scar substrates with multiple exit sites (MES) identified during pace-mapping have improved freedom from recurrent VT and PMI of VT predicts successful sites of termination during ablation.

Methods and Results

High-density mapping was performed in all subjects to delineate scar (0.5-1.5mV). Sites with abnormal electrograms (EGMs) were tagged, stimulated (bipolar 10 mA at 2 ms), and targeted for ablation. MES was defined as more than one QRS morphology from a single pacing site. Pace-mapped induction (PMI) was defined as initiation of VT during pace-mapping (400-600ms).

In a two-year period, 44 consecutive patients with scar-mediated VT underwent mapping and ablation. MES were observed during pace-mapping in 25 patients (57%). At 9 months, 74% patients who exhibited MES during pace-mapping had no recurrence of VT compared to 42% of those without MES observed (p=0.024), with an overall freedom from VT of 61%. Thirteen patients (30%) demonstrated PMI and termination of VT was seen in 95% (18/19) of sites where ablation was performed.

Conclusions

During pace-mapping, EGMs that exhibit MES and PMI may be specific for sites critical to reentry. These functional responses hold promise for identifying important sites for catheter ablation of VT.

Scar-mediated ventricular tachycardia (VT) is hemodynamically unstable in over 70% of cases, which significantly limits mapping for diastolic activity during tachycardia.1 Therefore, substrate-based techniques in sinus rhythm based on scar border zone delineation and identification of abnormal electrograms that represent areas of slow conduction are frequently targeted for ablation. 2-7 Pace-mapping can serve as a surrogate for identification of exit sites by matching VT morphology, but the most conclusive demonstration of a critical isthmus requires entrainment of VT and/or termination of VT during ablation. 8, 9

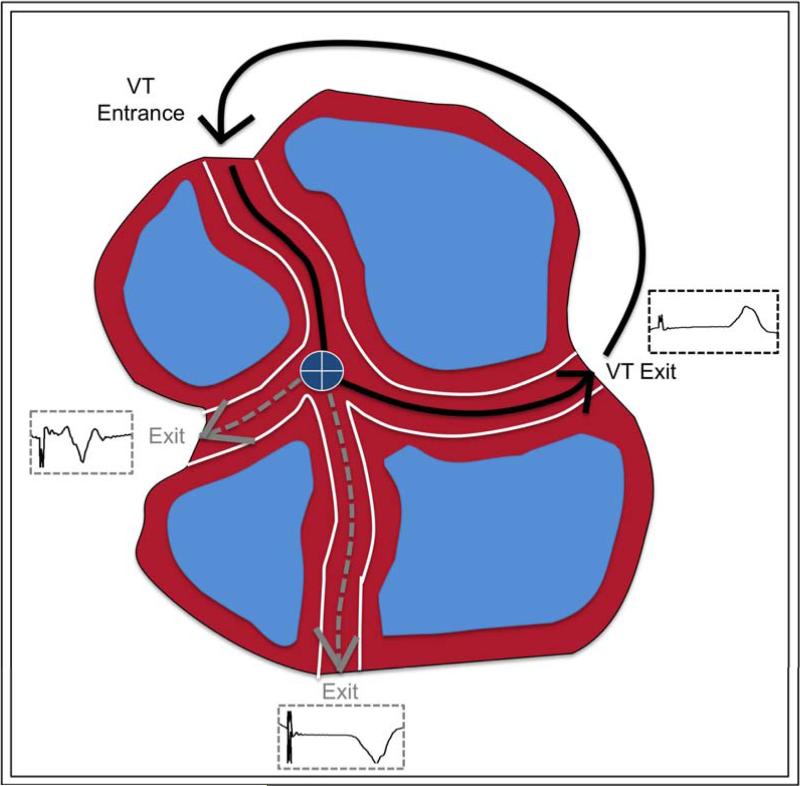

Pacing within a scar can sometimes reveal multiple exits, which can produce distinctly different QRS morphologies during pacing. Further, if slow conduction is encountered deep within a scar at the site of stimulation, reentry of the index paced beat can by itself induce VT without the need for a programmed extrastimulus. The aim of this study is to describe two functional responses to pace-mapping at abnormal electrogram sites within scar: 1) multiple exit sites (MES), or pace-maps that exhibit more than one morphology 2) induction of VT by pace-mapping, termed pace-mapped induction (PMI).

We hypothesized that in patients with scar-mediated VT, those with MES identified during pace-mapping followed by ablation have improved freedom from recurrent VT and PMI of VT at a relatively slow drive train predicts successful sites of termination during ablation.

METHODS

PATIENT SELECTION

Data obtained from consecutive patients referred for catheter ablation of scar-mediated VT over a two-year period were retrospectively analyzed. Patients with evidence of electroanatomic scar from ischemic cardiomyopathy (ICM), nonischemic cardiomyopathy (NICM), hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC), valvular cardiomyopathy due to rheumatic heart disease, and sarcoidosis were included. The diagnosis of NICM was based on the absence of coronary artery disease (>75% stenosis), prior myocardial infarction, or significant valvular disease. The diagnosis of ICM was established by prior history of infarction with Q waves, focal wall motion abnormality, or fixed perfusion defect correlated with coronary stenosis or prior intervention. All studies were performed under general anesthesia after pre-procedural transesophageal echocardiography excluded intracardiac thrombus. Epicardial mapping was performed as clinically indicated at the discretion of the operator. The Institutional Review Board at UCLA approved review of the retrospective data.

ELECTROANATOMIC MAPPING AND PACE-MAPPING

Endocardial mapping was performed through a transseptal approach. Transseptal puncture was performed using a Brockenbrough needle (BRK-1), with adjunctive radiofrequency energy (RF, Valley Lab, PA, 30W) applied in cases of aneurysmal or thick interatrial septal anatomy. An activated clotting time goal of 250-350 seconds was maintained throughout the procedure with intravenous heparin. Epicardial access was obtained by percutaneous subxiphoid pericardial puncture and was performed surgically in patients with previous thoracotomy, as described previously. 10-12

Electroanatomic voltage mapping was performed during the baseline rhythm, which was either sinus or paced, with a CARTO (Biosense Webster, Diamond Bar, California) or NavX EAM system (Ensite, St. Jude Medical, Minnetonka, MN) as previously described.7, 13, 14 Higher density mapping was performed within scar and at border zones. Bipolar signals were filtered at 5 to 500 Hz and displayed at 100 mm/s.

Abnormal electrograms (EGM) were defined as sites with low voltage (<1.5 mV) with fractionation, split potentials, or late potentials (LP). LP were defined as electrograms exhibiting a component with a distinct onset after the QRS. Fractionated signals (multiple high-frequency deflections) and split potentials, with more than one component separated by >20 ms isoelectric segment, were tagged. Pace-mapping was performed (10mA at 2 ms, 400-600ms cycle length) at these sites for comparison with the 12 lead template of the clinical or induced VT. A perfect pace-map match was defined as a 12/12 lead match and good pace-map match was defined as a ≥ 10/12 match.

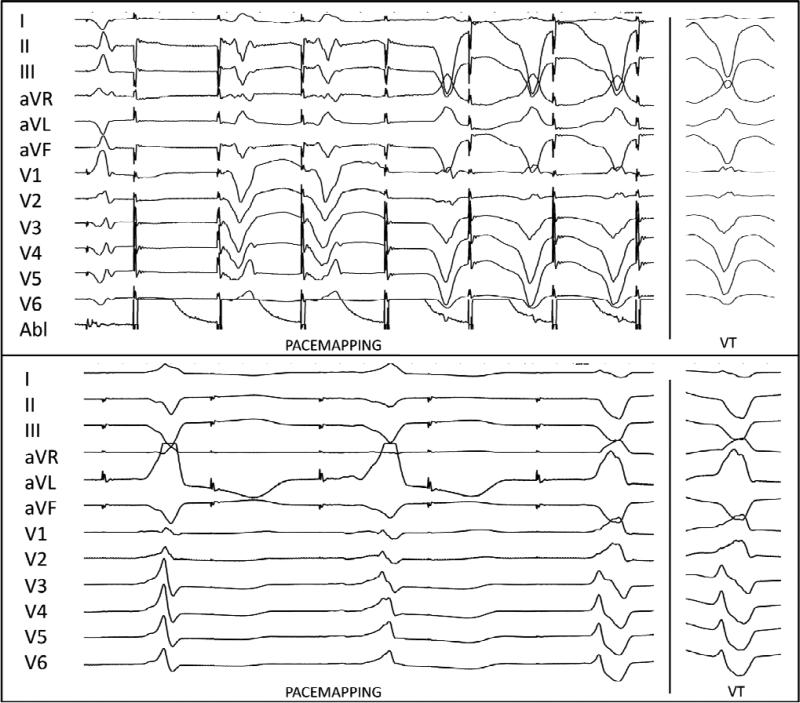

A multi-exit site (MES) was defined as an abnormal EGM site that exhibited two or more distinct QRS morphologies (<10/12 match to be distinct from each other) during the same pace-mapping drive. A schematic of MES from a single pace-map site within a theoretical isthmus is show in FIGURE 1. The stimulus to QRS (S-QRS) intervals were measured to each different morphology and the differences between S-QRS within the same drive between different morphologies was calculated (delta S-QRS). Catheter stability was confirmed by fluoroscopy, electroanatomic mapping position, and electrogram reproducibility. The first beat of pacing was not counted as a distinct morphology to minimize the possibility of fusion. At least two instances of consecutive QRS complexes of a given morphology were required to minimize the chance of counting a premature ventricular beat. An MES was considered a matched MES for VT if any one of the morphologies produced from pacing exhibited a ≥10/12 match with a targeted VT. (FIGURE 2) 2:1 conduction, or exit block, was included if consistent and reproducible (>3 conducted beats). (FIGURE 2, lower) Three independent observers analyzed the pace-map drive trains to confirm distinct morphologies in a given MES.

Criteria for MES during pace-mapping

| • Stable catheter position at abnormal electrogram site |

| • Pacing drive at 400-600ms (10mA, 2 ms) |

| • Two or more distinct QRS morphologies seen during same pacemap drive |

| • Distinct QRS requires <10/12 match between two morphologies |

| • First captured beat excluded |

| • Two occurrences of a morphology required |

FIGURE 1.

Schematic of MES: Three exit morphologies from a single pacing site (center, marked +). Blue areas present scar, or replacement fibrosis.

FIGURE 2.

Upper. Two morphologies with two different stimulus latencies seen during pace-mapping within dense scar. The second morphology matches the targeted VT. Lower. Three distinct morphologies with 2:1 exit block from a pace-map site with last beat matched for targeted VT.

CATHETER ABLATION AND FOLLOW-UP

VT was induced with programmed extrastimulus testing from the RV apex, outflow tract before or after creation of the EAM. If the patient was non-inducible with programmed stimulation from the RV, stimulation was performed from the LV. Drive cycles of 600 and 400 ms, with decrement by 10 ms until refractoriness or 200 ms, were used with up to four extrastimuli. Induced VTs were stored as a template; a targeted VT had at least one of the following characteristics 1) similar to 12-lead of presenting VT, (when available), 2) similar in cycle length to that seen on ICD interrogation 3) reproducibly inducible. All sustained VTs seen during the procedure, either spontaneous, mechanically or induced by programmed stimulation were counted. Ventricular flutter or sine wave tachycardia that degenerated into ventricular fibrillation was not counted as a VT morphology or targeted.

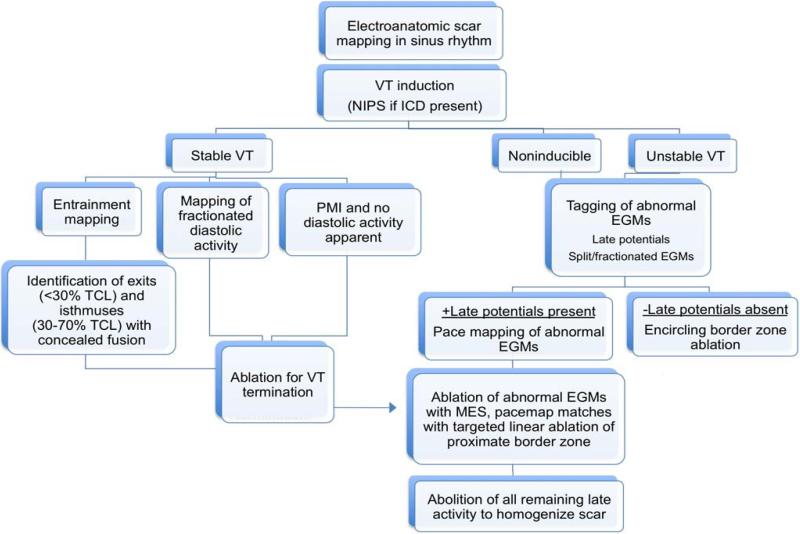

If ventricular tachycardia was hemodynamically tolerated, entrainment mapping was attempted at sites demonstrating diastolic activity. An isthmus was defined as a site where 1) pacing for entrainment performed 20-40 ms shorter than tachycardia cycle length (TCL) with a post-pacing interval within 30 ms of TCL with concealed fusion and equivalent stimulus-QRS interval to EGM-QRS (30-70%TCL) interval or 2) VT terminated during ablation. 9, 15

Cases in which VT was induced from pace-mapping (10mA at 2 ms, 400-600ms cycle length) were termed pace-mapped induction (PMI). A PMI was considered matched if the pace-map morphology exhibited a 10/12 match with the immediately induced VT. As these PMI sites were represented by abnormal electrograms in sinus rhythm, ablation was attempted in these regions regardless of whether diastolic activity was seen. Termination of VT was recorded and correlated with PMI sites.

In cases where an induced VT was not hemodynamically tolerated, a strategy of ablating abnormal electrogram sites with good pace-maps (>10/12 match), all MES identified, and all LP was employed. Linear lesions were also created at border zones deemed to represent exit sites by pace-mapping. This strategy was also employed after a tolerated VT was successfully eliminated to achieve extensive substrate modification in all patients. If the patient was noninducible for VT, abolition of all late potentials and mapped abnormal electrograms was performed. If LPs were not identified, an encircling border zone lesion set was made. (See FIGURE 3 for mapping and ablation protocol)

FIGURE 3.

Approach to mapping and ablation of VT. NIPS=noninvasive programmed stimulation , ICD=implantable cardioverter defibrillator, TCL=tachycardia cycle length, EGM=electrogram

Ablation was performed an open-irrigated catheter (ThermoCool, 3.5 mm, Biosense-Webster, Diamond Bar, CA) at 30-50W, temperature limit 45°C @ 30 ml flow rate. Radiofrequency energy was applied for 60 seconds per lesion. Ablation lesions were tagged on the electroanatomic map and lesions were considered effective if they showed at least one of the following: a diminution or abolishment of the local electrogram, failure to capture at 10mA at 2 ms pacing, or impedance drop >10Ω.

After ablation was performed in the region of the targeted VT, programmed stimulation was repeated with ventricular extrastimulus testing at drive cycles of 600 and 400 ms, with decrement by 10 ms until refractoriness or 200 ms, up to four extrastimuli at a minimum of two sites. If an inducible VT had the same morphology as one seen during the case or was tolerated, it was re-targeted. Acute procedural results were categorized into three groups 1) complete success- noninducible after ablation for all VTs 2) partial success-inducible for non targeted VT 3) failure 16. Recurrence of VT after hospital discharge was assessed by patient interview and interrogation of ICD.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

All symmetric continuous data are summarized with mean± SD and compared using unpaired student t-test. Asymmetric continuous data are summarized with medians and ranges. Comparison of proportions and categorical variables was performed using the Fisher exact test. Time-to-event curves for VT recurrence during the follow-up period were calculated by the Kaplan-Meier method and compared using the log-rank test. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Between March 2009 and February 2011, 44 consecutive patients with scar-mediated VT (ICM=26, NICM=10, ARVD=2, HCM=2, valvular CM=2. sarcoid CM=2) underwent mapping and ablation. The mean age was 64±13 years and all but two patients were male. The average ejection fraction was 30±12% and 41% of patients did not have prior history of myocardial infarction. Seventy percent of patients failed amiodarone therapy and 39% had prior ablation. Epicardial mapping was performed in 22 patients (50%), of which 2 were performed with surgical access due to prior cardiac surgery.

Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1, stratified by the presence of MES during pace-mapping. No statistically significant differences in baseline characteristics were found between the two groups. There was a trend toward a higher incidence of history of myocardial infarction in the MES group, although this difference was not statistically significant.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| MES + (n=25) | MES - (n=19) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 66±11 | 60±14 | p=0.15 |

| Sex, male (%) | 25 (100) | 17 (89) | p=0.18 |

| LVEF % | 31±10 | 29±14 | p=0.52 |

| Prior MI (%) | 18 (72) | 8 (42) | p=0.06 |

| ICD (%) | 25 (100) | 18 (90) | p=0.43 |

| Prior ablation (%) | 12 (48) | 5 (26) | p=0.33 |

| Amiodarone (%) | 16 (64) | 15 (79) | p=0.33 |

The median number of points mapped for the left ventricle was 442 points (range 1088-1604) on the endocardium and 637 points (range 350-841) on the endocardium. The right ventricle was mapped in 7 patients with a median of 195 points (range 114-249). Amongst those with ICM, infarct location delineated by electroanatomic mapping was anterior in 42% (11/26), inferior in 31% (8/26), and inferolateral in 27% (7/26). The mean mapping density in low voltage regions (<1.5mV) was 2.9 points/cm2 (range 0.6-7.2 points/cm2).

Three patients presented with incessant VT and two patients were noninducible for VT during pre-ablation programmed stimulation. In the remaining 39 patients, VT was induced from the right ventricle in 90% (35/39) and 10% (4/39) required LV stimulation to induce VT. Entrainment mapping was performed in 23% of patients (10/44).

Pace-mapping and Multiple Exit Sites (MES)

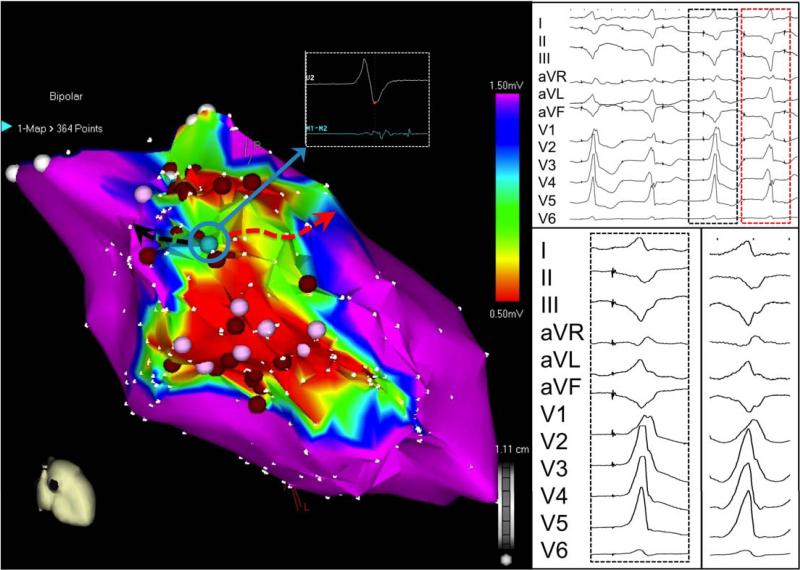

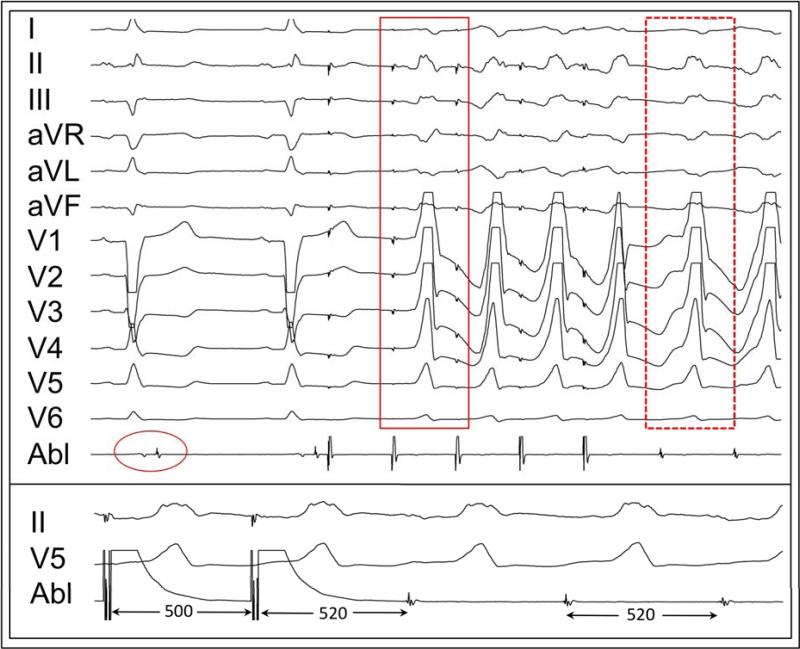

Pace-mapping was attempted at 55±33 sites with abnormal electrograms per patient. Amongst these, 17±15 sites failed to capture during pacing (electrically unexcitable scar) and a mean of 38±20 pace-maps were generated per patient. MES were observed during pace-mapping in 57% of patients (25/44). Of these, one morphology exhibited a pace-map match of ≥10/12 for a targeted VT in 40% (10/25) of patients. No differences were seen in the number of pace-maps per patient between those with MES and those without MES (39±22 vs 38±20). A typical patient with MES with 3:2 conduction out of the pacing site showing two distinct morphologies is shown in FIGURE 4.

FIGURE 4.

Pace-mapping in patient with inferior infarction from an electrogram with LP results in 3:2 conduction out of scar. Two morphologies with different stimulus latencies are seen (red and black dashed boxes) and the first morphology is a good match for a targeted VT. Red circles represent ablation lesions within dense scar and pink circles are other sites where pace-mapping was performed. Note that this MES lies within a potential channel, flanked by two areas of dense scar (red). LP= late potential. Need time scale for rather upper panel

There was no difference in the median number of VTs induced was in those that did not demonstrate MES (3 VTs; range 0-6) compared to those with MES (3 VTs; range 0-7). The mean VT cycle length was 406±91ms in those with MES and 397±82ms in those without MES (p=0.73). Twenty-eight percent of patients with MES (7/25) also exhibited 2:1 exit block during pace-mapping. Alternation between two distinct morphologies, or pace-map “alternans”, was seen in 16% (4/25) patients.

At a total of 42 MES, 31% exhibited LP, with a median onset of 21 ms (range 0-110 ms) after the QRS. The median electrogram voltage at an MES site was 0.24 mV (range 0.04-1.5 mV). Thirty-one percent (13/42) were located in border zone tissue (0.5-1.5mV), 50% (21/42) were in dense scar (<0.5mV), and 19% (8/42) were <0.1mV. The median S-QRS was 86ms (range 28-332 ms) at MES and the median delta S-QRS between two morphologies during the same pacing train was 22 ms (range 2-229 ms). Concealed entrainment of an isthmus was demonstrated in 28% (7/25) of patients with MES compared to 13% (2/16) of patients who did not exhibit MES.

Termination of a targeted VT was seen in 13/25 (52%) of patients with MES compared to 7/19 (37%) without MES. Acute procedural success tended to be higher in those who exhibited MES (70% vs 56% complete success, p=0.35). No differences in radiofrequency duration (47±21 min vs 40±25 min, p=0.33) and procedure time (6.4±1.3 hrs vs 6.7±1.9 hrs, p=0.56) were seen between those with MES and those without, respectively.

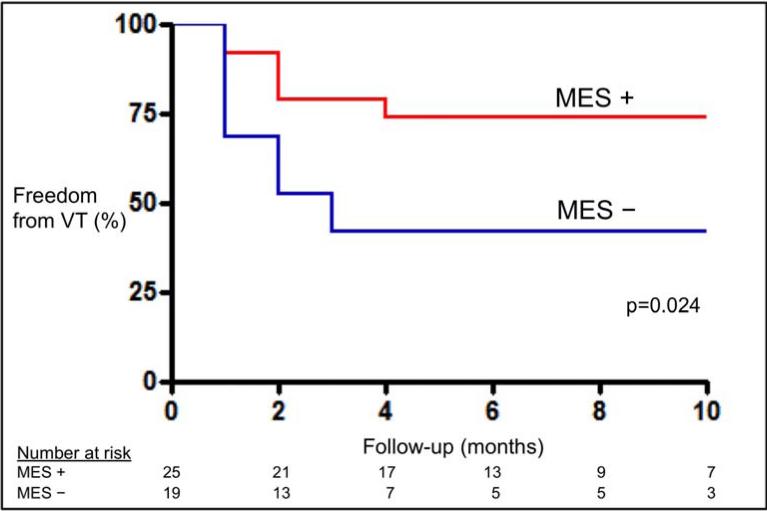

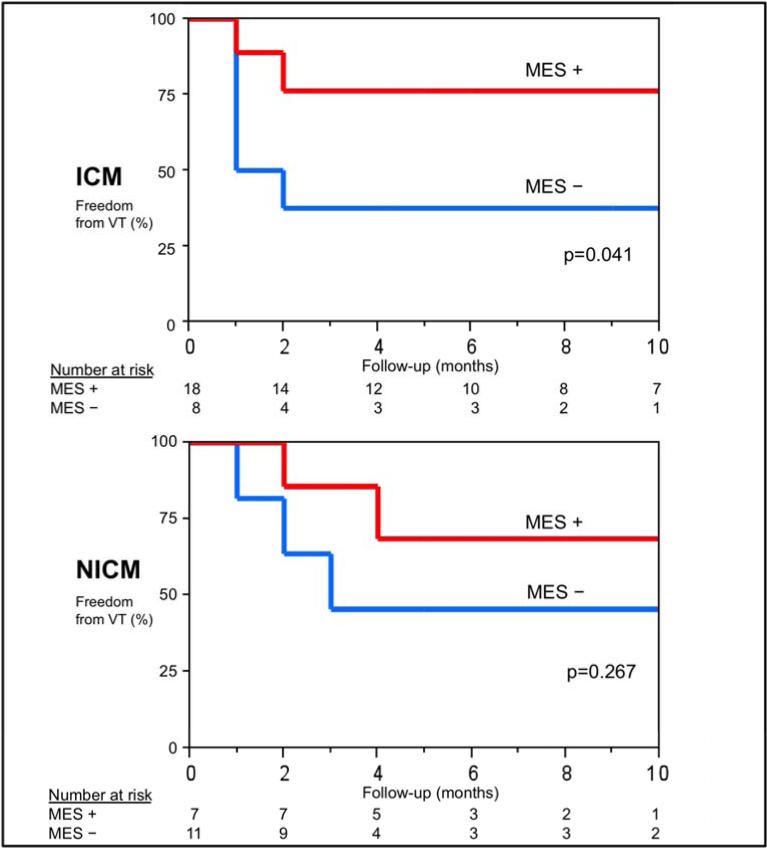

The overall success rate for the entire cohort of 61% with an average follow-up of 9±8 months. At 9 months, 74% patients who exhibited MES had freedom from VT recurrence compared to 42% of those without MES observed (p=0.024). (FIGURE 5A) Amongst patients with ICM (n=26), those who exhibited MES (n=18) had higher freedom from VT recurrence at 9 months compared to those who did not have MES (n=8) (76% vs. 38%, p=0.041). When comparing patients with scar not due to prior infarction (n=18; NICM, HCM, ARVD, RHD, and sarcoid), a similar trend in freedom from recurrent VT was seen between patients with MES compared to those who did not have MES, although not statistically significant (69% vs. 45%, p=0.267). (FIGURE 5B) Patients that exhibited 2:1 conduction during pace-mapping had a 71% freedom from VT. No significant difference in VT recurrence was seen between those with matched MES and those who did not have any MES morphology match a targeted VT.

FIGURE 5a.

Kaplan-Meier curves comparing VT recurrence in patients with MES and without MES seen during mapping and ablation.

FIGURE 5b.

Kaplan-Meier curves comparing VT recurrence in patients with MES and without MES in ICM (above) and non-ICM groups (below).

Pace-mapped Induction (PMI)

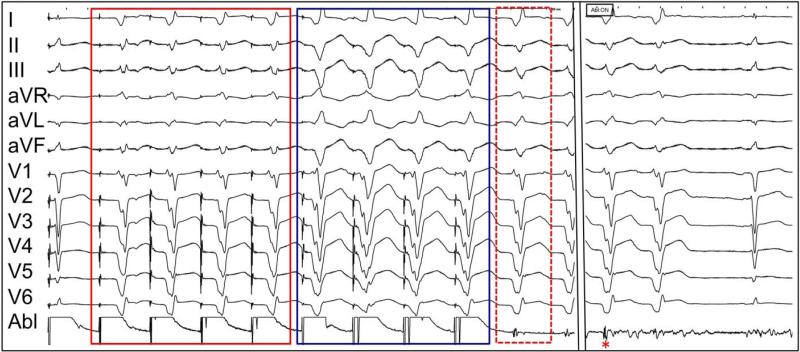

PMI was observed in 30% (13/44) of patients. The mean cycle length of a pace-map drive was 474±73 ms. Concealed entrainment of an isthmus was demonstrated in 46% (6/13) and termination of VT during ablation was seen in 92% (12/13) of patients with PMI. (FIGURE 6) A perfect-matched PMI was seen in 54% (7/13), a good-matched PMI was seen in 31% (4/13) and non-matched PMI in 15% (2/13). In one patient, MES was seen during PMI and VT terminated abruptly (1.2 sec) at this site during ablation. (FIGURE 7)

FIGURE 6.

Upper. Pace-mapped induction (solid red box) is a perfect match for the induced VT (dashed red box) at a site with LP. Lower. Concealed entrainment was demonstrated at this site prior to ablation.

At a total of 21 PMI sites, the median electrogram voltage at a PMI site was 0.2 mV (range 0.04-1.38 mV). Twenty-nine percent (6/21) were located in border zone tissue (0.5-1.5mV), 52% (11/21) were in dense scar (<0.5mV), and 19% (4/21) were <0.1mV. LP was seen in 19% (4/21) of PMI sites with a median onset 18 ms (range 15-40ms) after the QRS. The median S-QRS was 102 ms (range 28-250 ms) at PMI sites. In 19% (4/21) of the PMI sites, diastolic activity was not apparent on filtered electrogram recordings, although all terminated during ablation at that site. In the remaining 17 sites, where diastolic activity was seen, 71% had an EGM-QRS during VT within 30 ms of S-QRS during pace-mapping from sinus rhythm.

Ablation was attempted at 19/21 PMI sites and termination was seen in 95% (18/19) of cases at the location of induction. In three of these cases, termination of VT required additional radiofrequency application in the same region of the PMI. Termination of VT occurred at a mean duration of 8.2±9.3 seconds (range 1.1-32.0 seconds) into ablation.

While the presence of PMI was strongly associated with termination of VT, it was not predictive of clinical success. The median number of VTs induced was higher in the group where PMI was observed (3.5 VTs; range 1-7) compared to those without (2 VTs; range 0-6, p=0.038). No significant differences in radiofrequency duration (50±25 min vs 41±21 min, p=0.20) or procedure time (6.5±1.4 hrs vs 6.6±1.6 hrs, p=0.83) were seen between patients with and without PMI, respectively. Acutely, 38% of patients with PMI were rendered noninducible post ablation. Patients with PMI of VT had a 54% freedom from VT recurrence with median follow-up of 9 months.

DISCUSSION

The major findings of the present study for patients undergoing scar-mediated VT ablation: 1) Identification and ablation of MES seen during pace-mapping was associated with higher VT-free survival. 2) Sites with PMI of a targeted VT strongly predicted acutely successful ablation sites.

The demonstration of multiple QRS morphologies with pacing at a fixed site identifies regions within scar that have access to more than one exit site. These sites may be surrogates for common conducting channels, or isthmuses and in patients where MES can be identified and ablated, outcomes could potentially be improved when compared to patients in whom these sites are not identified during mapping.

Definitive proof of an isthmus relies on specific criteria during entrainment mapping. 9, 15 While entrainment requires hemodynamic toleration of VT, termination during ablation or mechanical ‘bump’ have also been used as surrogates for channels critical to reentry. In the majority of cases where VT is not tolerated, the finding of longer stimulus latency for the same matched pace-map has been applied in clinical practice to identify channel orientation and proximity to the exit site within electroanatomic scar geometry.17 While some advocate more extensive substrate modification to achieve scar homogenization, or the complete abolition of abnormal electrograms and late activity 14, 18, 19, a method to prioritize or screen for the functional importance of an abnormal electrogram identified in sinus rhythm beyond pace-map morphology would have meaningful utility.

In this cohort, even subtle alterations in QRS morphology (<10/12 match) observed were termed MES. Traditionally, pace-mapped sites that do not match the targeted VT are abandoned. Importantly, the finding of MES from a single site suggests that pace-map matching is not essential for isthmus identification. Further proof of this concept is supported by the fact that the majority of PMI where termination during ablation occurred were not matched for the VT. This finding is consistent with previously published observations that demonstrate the limitations of pace-mapping. In a cohort of 18 patients with postinfarct monomorphic VT, Stevenson et al demonstrated a nonmatched pace-map during sinus rhythm in 21% (6/28) of sites where concealed entrainment was demonstrated. Further, pace-map matches were seen in 29% of site where entrainment showed manifest fusion.17

Several mechanisms to account for the inherent limitations of pace-mapping have been proposed. Factors that determine which exit site shows preferential conduction during reentry are not fully understood, but potentially are governed by refractory periods, anisotropic conduction, and conduction velocity.20, 21 Importantly, pacing in sinus rhythm from a point-source with radial impulse propagation may not mimic a broad reentrant wavefront emerging from an exit site (eikonal relationship). A different QRS morphology during pace-mapping or VT may result from myocardial fusion of two or more wavefronts from different exits. Areas of functional block that facilitate reentry during VT may be absent during pace-mapping, resulting in a different QRS morphology.17 While pacing was performed at the same output for all patients, altering pacing output may change the virtual electrode of pacing, resulting in different myocardial capture, “near” and “far”. 22 While not specifically examined the present study, pacing at different rates may alter functional properties of circuit conduction and the potential site of exit.

Consistent with the observed phenomenon of MES, 25-40% of patients with post infarct VT exhibit pleomorphism, or spontaneous morphological changes during sustained VT.23, 24 Costeas et al. used activation mapping in a canine model to show that distinctly different morphologies of reentry emanated from the same region, but were altered by different exit routes out of the circuit.25 The evidence of a “shared isthmus” was reproduced by Kimber et al. who described intraoperative mapping findings of patients with pleomorphic VT. In 10 of 14 episodes where QRS morphological shifts were observed, little (<2 cm) or no change in the site of origin was observed, suggesting a switch in only the site of wavefront exit and epicardial breakthrough.

While the presence of late potentials in sinus rhythm indicates an area of local conduction slowing, the present findings suggest that functional conduction information beyond a 12-lead morphological match is available during pace-mapping. Slow conduction (S-QRS>40ms) has been demonstrated during pace-mapping of fractionated sinus rhythm electrograms.26. In the present study, 2:1 conduction block out of the paced site was observed and may aid in the identification of areas of slower conduction, which may be critical to reentry of a targeted VT. One patient in this series demonstrated Wenckebach conduction out of the pacing site with the same QRS morphology.

The induction of VT during a relatively slow pacing train (400-600ms) was highly specific for an isthmus as termination of VT was seen in the all but one case when ablation was performed at these sites. Induction of scar-mediated VT characteristically requires extrastimulus programmed stimulation to facilitate unidirectional block. 27, 28 If sufficiently slow conduction is present at the site of stimulation, a programmed extrastimulus may not be required to initiate reentry. Consistent with MES responses to pace-mapping, sites that were non pace-matched for the clinical VT that resulted in PMI were still effective targets for arrhythmia termination.

Further studies on stimulation within scar and abnormal electrograms are necessary as presently used induction protocols are performed with the right ventricular apex and outflow tract. In our cohort, 10% of patients required LV stimulation to induce VT after being non-inducible from the RV. One patient was non-inducible from two sites in the right ventricle and had a PMI of the clinical VT from the epicardium of the left ventricle. The presence of PMI was not predictive of clinical success in the present study and this is likely due to the presence of multiple VTs from a complex substrate that cannot be entirely modified by the termination of a single VT morphology. This would suggest that more extensive substrate modification is required to improve long-term outcomes.

LIMITATIONS

This cohort represents a single-center experience and the relatively small sample size limits the ability to draw strong, generalizable conclusions. Specific to our center, general anesthesia is used in all patients, which may result in slower VT cycle lengths and unstable hemodynamic status for any given sustained VT. Additionally, epicardial mapping was implemented in 50% of patients, as 39% of patients referred had prior failed endocardial ablation and 41% did not have history of myocardial infarction. Further studies are necessary and the present findings should be reproduced at other specialized centers.

While the findings of paced stimulus latency to QRS onset suggests slow conduction out of a conducting channel, a critical isthmus and bystander site cannot be differentiated by pace-mapping alone. However, conduction properties during tachycardia may be different during pace-mapping, making the interpretation of S-QRS during pace-mapping in comparison with S-QRS during entrainment unreliable.

Additionally, comprehensive ablation targeting all LP and matched pace-maps at abnormal electrogram sites were performed in both groups, with and without MES. The proof for specificity of MES for critical isthmuses would be stronger if ablation had been limited to only sites demonstrating MES. However, this study was analyzed retrospectively for proof of concept; prospective studies will be required. In the present study, it remains that given the same intended approach, patients with MES sites identified had significantly improved freedom from VT. In order to minimize bias in interpretation of multiple exit sites, we used three independent observers to determine if distinctly different morphologies were present.

While there were more patients with ICM in the MES group, this difference was not statistically significant. As ablation outcomes have been shown to be superior in ICM compared to NICM patients 13, the differences in VT recurrence between patients with and without MES may be amplified by this trend towards a higher proportion of ICM etiology in MES. However, within the ICM cohort (n=26), the same significant differences in clinical outcomes were observed between patients with and without MES. Additionally, the same trend was seen in the group with non-infarctive scar (n=18), although this was not statistically significant.

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

The present findings provide further mechanistic insights into mapping of scar-mediated VT during sinus rhythm. The goal of VT ablation is the rapid and accurate identification of a critical isthmus. While the proof of an isthmus traditionally requires entrainment mapping during tachycardia, the identification of such sites based on sinus rhythm observations is highly desirable. The finding of MES at a site with abnormal EGM during substrate mapping provides functional conduction characteristics within scar and may suggest a potential isthmus or common conduction channel. Additionally, the induction of VT during pace-mapping may imply an area of obligate slow conduction for a given reentrant circuit and strongly predicts arrhythmia termination during ablation.

CONCLUSION

PMI of VT is strongly predictive of termination during ablation and the finding of MES is associated with higher freedom from VT recurrence. These functional responses seen during pace-mapping hold promise for identifying important sites for catheter ablation of VT.

Ablation for scar-related ventricular tachcyardias targets isthmuses critical to the initiation and maintenance of reentry. Because the majority of VTs are hemodynamically untolerated, potential surrogates for isthmuses that can be identified in sinus rhythm during substrate-based ablation of VT are desirable. The present study introduces two new functional responses seen during pace-mapping that are potential isthmus markers. The first, multiple pace-map QRS morphologies seen during pacing at a single site, may indicate a shared common conducting channel that has access to multiple exit sites. The second, induction of VT during a relatively slow pace-mapping drive train from a site within the scar, may similarly indicate pacing in an isthmus. These findings may be a useful method to “screen” sites with abnormal electrograms. These mechanistic phenomena also illustrate that matching QRS morphology of pace-mapping with VT is not necessary to define a site critical to reentry.

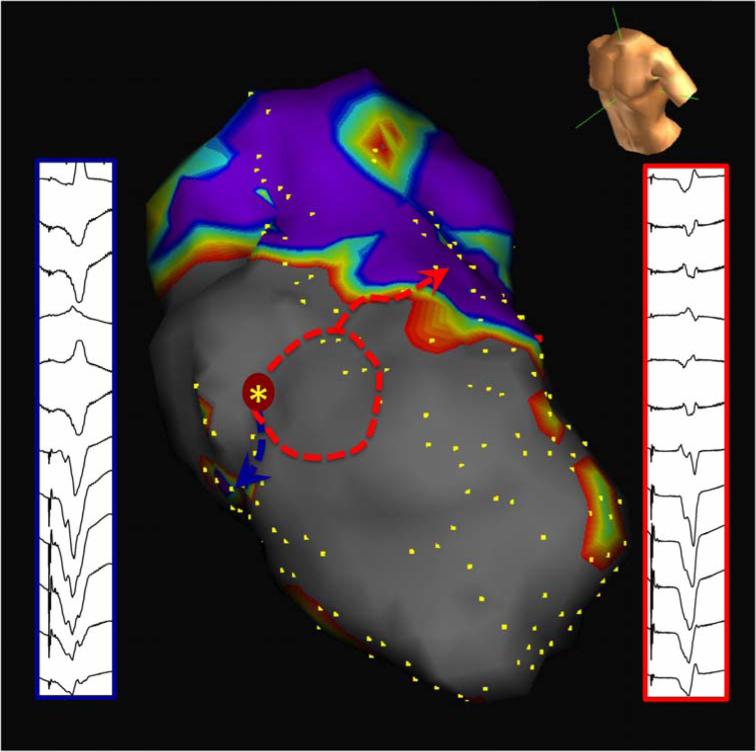

FIGURE 7a.

Two-exit site pace-mapped induction. Proof of both MES and PMI as isthmus surrogate. The first morphology (red solid box) is a closer match to the induced VT (red dashed box) than the second morphology (blue box). Ablation at this site (red asterisk), despite the absence of overt diastolic activity, resulted in prompt termination of VT.

FIGURE 7b.

Construct of two exits on electroanatomic map during pacemapped induction (blue and red arrows) attached to the same reentrant VT circuit in the same patient with anteroseptal infarction. Voltage threshold displayed at 0.5-1.5mV.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the NHLBI (R01HL084261) to KS

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES:

RT: Lecture honoraria <10K, Boston Scientific, St. Jude

NG: Lecture honoraria <10K, Biotronik

KS: Lecture honoraria <10K, St. Jude

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Josephson ME. Electrophysiology of ventricular tachycardia: an historical perspective. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2003;14:1134–1148. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2003.03322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marchlinski FE, Callans DJ, Gottlieb CD, Zado E. Linear ablation lesions for control of unmappable ventricular tachycardia in patients with ischemic and nonischemic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2000;101:1288–1296. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.11.1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Soejima K, Suzuki M, Maisel WH, Brunckhorst CB, Delacretaz E, Blier L, Tung S, Khan H, Stevenson WG. Catheter ablation in patients with multiple and unstable ventricular tachycardias after myocardial infarction: short ablation lines guided by reentry circuit isthmuses and sinus rhythm mapping. Circulation. 2001;104:664–669. doi: 10.1161/hc3101.093764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reddy VY, Reynolds MR, Neuzil P, Richardson AW, Taborsky M, Jongnarangsin K, Kralovec S, Sediva L, Ruskin JN, Josephson ME. Prophylactic catheter ablation for the prevention of defibrillator therapy. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2657–2665. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bogun F, Good E, Reich S, Elmouchi D, Igic P, Lemola K, Tschopp D, Jongnarangsin K, Oral H, Chugh A, Pelosi F, Morady F. Isolated potentials during sinus rhythm and pace-mapping within scars as guides for ablation of post-infarction ventricular tachycardia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:2013–2019. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.12.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bogun F, Bender B, Li YG, Groenefeld G, Hohnloser SH, Pelosi F, Knight B, Strickberger SA, Morady F. Analysis during sinus rhythm of critical sites in reentry circuits of postinfarction ventricular tachycardia. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2002;7:95–103. doi: 10.1023/a:1020832502838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nakahara S, Tung R, Ramirez RJ, Gima J, Wiener I, Mahajan A, Boyle NG, Shivkumar K. Distribution of late potentials within infarct scars assessed by ultra high-density mapping. Heart Rhythm. 2010;7:1817–24. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2010.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Josephson ME, Waxman HL, Cain ME, Gardner MJ, Buxton AE. Ventricular activation during ventricular endocardial pacing. II. Role of pace-mapping to localize origin of ventricular tachycardia. Am J Cardiol. 1982;50:11–22. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(82)90003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stevenson WG, Friedman PL, Sager PT, Saxon LA, Kocovic D, Harada T, Wiener I, Khan H. Exploring postinfarction reentrant ventricular tachycardia with entrainment mapping. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;29:1180–1189. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(97)00065-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sosa E, Scanavacca M, d'Avila A, Pilleggi F. A new technique to perform epicardial mapping in the electrophysiology laboratory. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 1996;7:531–536. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.1996.tb00559.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soejima K, Couper G, Cooper JM, Sapp JL, Epstein LM, Stevenson WG. Subxiphoid surgical approach for epicardial catheter-based mapping and ablation in patients with prior cardiac surgery or difficult pericardial access. Circulation. 2004;110:1197–1201. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000140725.42845.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Michowitz Y, Mathuria N, Tung R, Esmailian F, Kwon M, Nakahara S, Bourke T, Boyle NG, Mahajan A, Shivkumar K. Hybrid Procedures for Epicardial Catheter Ablation of Ventricular Tachycardia: Value of Surgical Access. Heart Rhythm. 2010;7:1635–43. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2010.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakahara S, Tung R, Ramirez RJ, Michowitz Y, Vaseghi M, Buch E, Gima J, Wiener I, Mahajan A, Boyle NG, Shivkumar K. Characterization of the arrhythmogenic substrate in ischemic and nonischemic cardiomyopathy implications for catheter ablation of hemodynamically unstable ventricular tachycardia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:2355–2365. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.01.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tung R, Nakahara S, Maccabelli G, Buch E, Wiener I, Boyle NG, Carbucicchio C, Della Bella P, Shivkumar K. Ultra High-Density Multipolar Mapping with Double Ventricular Access: A Novel Technique for Ablation of Ventricular Tachycardia. Journal of Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2011;22:49–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2010.01859.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stevenson WG, Soejima K. Catheter ablation for ventricular tachycardia. Circulation. 2007;115:2750–2760. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.655720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Della Bella P, De Ponti R, Uriarte JA, Tondo C, Klersy C, Carbucicchio C, Storti C, Riva S, Longobardi M. Catheter ablation and antiarrhythmic drugs for haemodynamically tolerated post-infarction ventricular tachycardia; long-term outcome in relation to acute electrophysiological findings. Eur Heart J. 2002;23:414–424. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2001.2804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stevenson WG, Sager PT, Natterson PD, Saxon LA, Middlekauff HR, Wiener I. Relation of pace mapping QRS configuration and conduction delay to ventricular tachycardia reentry circuits in human infarct scars. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;26:481–488. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(95)80026-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arenal A, Glez-Torrecilla E, Ortiz M, Villacastin J, Fdez-Portales J, Sousa E, del Castillo S, Perez de Isla L, Jimenez J, Almendral J. Ablation of electrograms with an isolated, delayed component as treatment of unmappable monomorphic ventricular tachycardias in patients with structural heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:81–92. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02623-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nault I, Maury P, Sacher F. Characterization of Late Ventricular Potentials as Ventricular Tachycardia Substrates and Impact of Ablation. Heart Rhythm. 2008:S227. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kadish A, Balke CW, Levine JF, Moore EN, Spear JF. Activation patterns in healed experimental myocardial infarction. Circ Res. 1989;65:1698–1709. doi: 10.1161/01.res.65.6.1698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kadish A, Shinnar M, Moore EN, Levine JH, Balke CW, Spear JF. Interaction of fiber orientation and direction of impulse propagation with anatomic barriers in anisotropic canine myocardium. Circulation. 1988;78:1478–1494. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.78.6.1478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Gelder LM, el Gamal MI, Tielen CH. Changes in morphology of the paced QRS complex related to pacemaker output. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1989;12:1640–1649. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.1989.tb01843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Della Bella P, Riva S, Fassini G, Giraldi F, Berti M, Klersy C, Trevisi N. Incidence and significance of pleomorphism in patients with postmyocardial infarction ventricular tachycardia. Acute and long-term outcome of radiofrequency catheter ablation. Eur Heart J. 2004;25:1127–1138. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2004.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilber DJ, Davis MJ, Rosenbaum M, Ruskin JN, Garan H. Incidence and determinants of multiple morphologically distinct sustained ventricular tachycardias. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1987;10:583–591. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(87)80201-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Costeas C, Peters NS, Waldecker B, Ciaccio EJ, Wit AL, Coromilas J. Mechanisms causing sustained ventricular tachycardia with multiple QRS morphologies: results of mapping studies in the infarcted canine heart. Circulation. 1997;96:3721–3731. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.10.3721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stevenson WG, Weiss JN, Wiener I, Rivitz SM, Nademanee K, Klitzner T, Yeatman L, Josephson M, Wohlgelernter D. Fractionated endocardial electrograms are associated with slow conduction in humans: evidence from pace-mapping. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1989;13:369–376. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(89)90514-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Piccini JP, Hafley GE, Lee KL, Fisher JD, Josephson ME, Prystowsky EN, Buxton AE. Mode of induction of ventricular tachycardia and prognosis in patients with coronary disease: the Multicenter UnSustained Tachycardia Trial (MUSTT). J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2009;20:850–855. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2009.01469.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Horowitz LN, Spielman SR, Greenspan AM, Josephson ME. Role of programmed stimulation in assessing vulnerability to ventricular arrhythmias. Am Heart J. 1982;103:604–610. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(82)90464-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]