Abstract

Striatal-enriched protein tyrosine phosphatase (STEP) is a brain specific protein tyrosine phosphatase that has been implicated in many neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease. We recently reported the benzopentathiepin TC-2153 as a potent inhibitor of STEP in vitro, cells and animals. Herein, we report the synthesis and evaluation of TC-2153 analogs in order to define what structural features are important for inhibition and to identify positions tolerant of substitution for further study. The trifluoromethyl substitution is beneficial for inhibitor potency, and the amine is tolerant of acylation, and thus provides a convenient handle for introducing additional functionality such as reporter groups.

Keywords: Phosphatase, Inhibitor, Alzheimer’s Disease, STEP, Redox

Striatal-enriched protein tyrosine phosphatase (STEP) is a neuron-specific phosphatase that regulates key signaling molecules involved in synaptic plasticity, which is critical to maintaining proper cognitive function.1 Enhanced levels of STEP activity have been observed in several neuropsychiatric diseases and neurodegenerative disorders and result in the dephosphorylation and inactivation of several neuronal signaling molecules, including extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1 and 2 (ERK1/2), proline-rich tyrosine kinase 2 (Pyk2), mitogen-activated protein kinase p38, and the GluN2B subunit of the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR).2

An increase in STEP likely contributes to the cognitive deficits in Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Indeed, AD mice lacking STEP have restored levels of glutamate receptors on synaptosomal membranes and improved cognitive function, results that suggest STEP as a novel therapeutic target for AD.3 We recently identified that 8-(trifluoromethyl)-1,2,3,4,5-benzopentathiepin-6-amine hydrochloride (TC-2153, Figure 1) is a novel inhibitor of STEP.4,5,6 The cyclic polysulfide of the benzopentathiepin pharmacophore effects potent inhibition by a redox reversible covalent bond with the catalytic cysteine in the phosphatase active site. This redox reversible mode of inhibition is reminiscent of well-known cellular mechanisms for redox regulation of protein tyrosine phosphatases.7,8 Importantly, TC-2153 enhanced the phosphorylation levels of the known STEP substrates GluN2B, Pyk2 and ERK1/2 in rat cortical neurons. Moreover the inhibitor reduced cognitive deficits in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) mice as measured by the established novel object recognition and Morris water maze tests.4

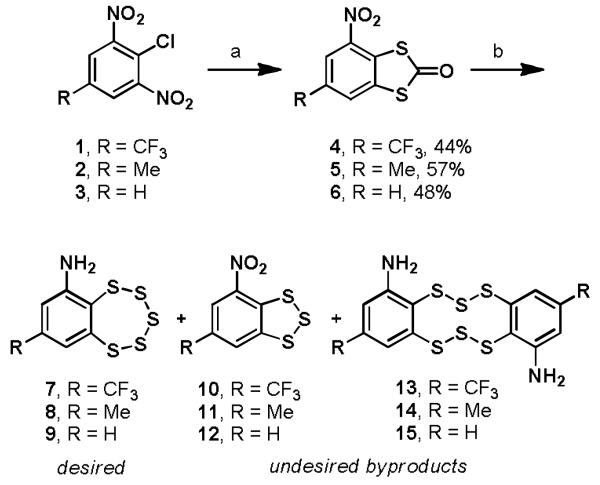

Figure 1.

Proposed SAR study of TC-2153.

To date, derivatives of TC-2153 have not been evaluated for STEP inhibition. Given the promising biological properties of TC-2153, we were motivated to define the essential characteristics of the molecule necessary for enzyme inhibition (Figure 1). First, we wished to explore the electronic effects of the inhibitor core to assess the importance of electronics on the redox-reversible inhibition of STEP. Secondly, we wanted to discover sites on the molecule tolerant of substitution to enable modulation of physicochemical properties such as solubility, for the introduction of reporter groups, or for the introduction of functionality to facilitate pull down assays and proteomic analysis.

To prepare the analogs, we first investigated the synthesis sequence for the preparation of TC-2153 as first reported by Kulikov and coworkers (Scheme 1).9 Elevated temperatures were required for the SNAr reactions with sodium dimethyldithiocarbamate when the less activated substrates 2 and 3 containing a simple methyl or proton substituent at the R position were used, with lower temperatures resulting only in a single nucleophilic substitution of the chloride. Consistent with a previous report,10 treatment of the intermediate nitrodithiolones 4–6 with NaSH yielded little to none of the desired products 7–9 except in the case of the trifluoromethyl substituted derivative 4, and even then the desired pentathiepin 7 was obtained in only 41% yield with numerous byproducts formed, including nitrotrithiole 10 (37%) and dimerization product 13 (5%).

Scheme 1.

Original synthesis of benzopentathiepin compoundsa

aReagents and conditions: (a) sodium dimethyldithiocarbamate, DMSO, rt or 150 °C; (b) NaSH, DMSO, rt.

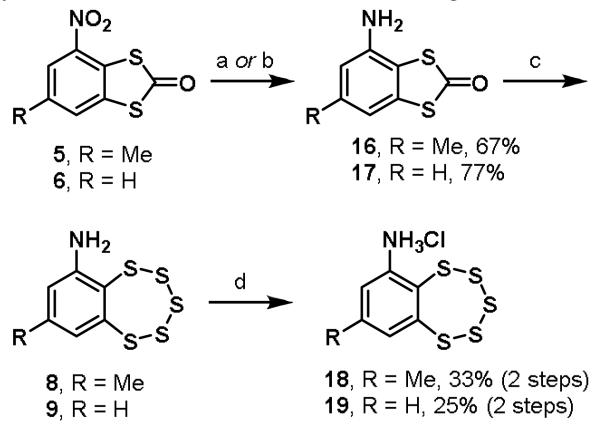

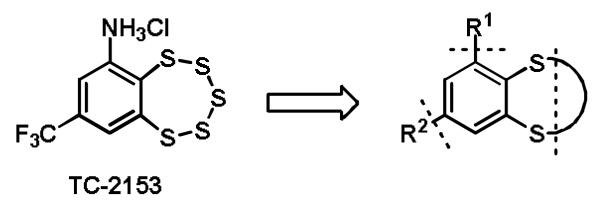

Due to the difficulty in obtaining the desired pentathiepin products for analogs lacking electron-deficient substituents, an alternative pathway was explored (Scheme 2). By first reducing the nitro group in dithiolones 5 and 6, then treating the free anilines 16 and 17 with sodium hydrosulfide in DMSO, we were able to synthesize the desired intermediate benzopentathiepins 8 and 9. Salt formation with HCl yielded the final inhibitor analogs 18 and 19. Further optimization of this sequence has been applied to the preparation of tens of grams of TC-2153.4

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of less electron deficient analogs 18 and 19a

aReagents and conditions: (a) NH4Cl, Zn0, EtOH, H2O, rt; (b) SnCl2, HCl, H2O, EtOH, 40 °C; (c) NaSH, DMSO, rt; (d) HCl, ether, rt.

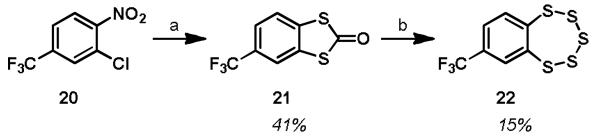

Analog 22, which does not contain an amine, was synthesized using an analogous procedure (Scheme 3). 2-Chloro-1-nitro-4-(trifluoromethyl)benzene, 20, was treated with sodium dimethylldithiocarbamate at elevated temperature to yield the dithialone 21. Treatment with NaSH in DMSO yielded the analog 22.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of TC-2153 analog 22a

aReagents and conditions: (a) sodium dimethyldithiocarbamate, DMSO, 200 °C; (b) NaSH, DMSO, rt.

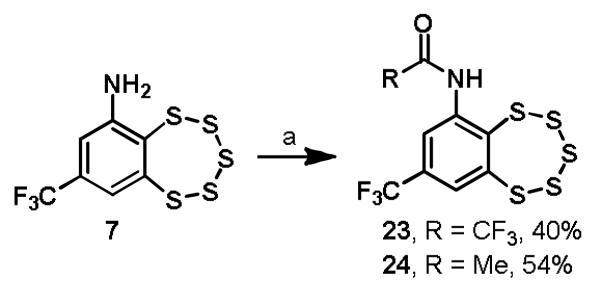

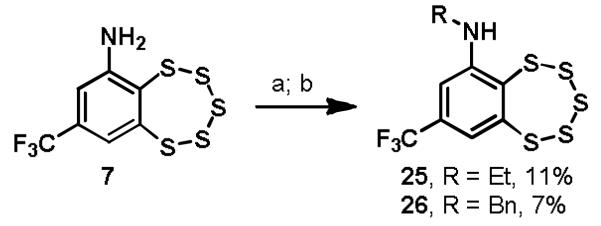

The amine provides a convenient handle for potentially adding solubilizing functionality or chemical labels, which has the potential of being introduced either by alkylation to maintain the basicity of the amine or by acylation. Acylation of intermediate 7 according to literature precedent with either trifluoroacetic anhydride or acetyl chloride yielded analogs 23 and 24, respectively (Scheme 4).11 Reductive amination of 7 with acetaldehyde or benzaldehyde provided N-ethyl and N-benzyl analogs 25 and 26 (Scheme 5).

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of TC-2153 analogs 23 and 24a

aReagents and conditions: (a) AcCl or TFAA, CH2Cl2, °C to rt.

Scheme 5.

Synthesis of TC-2153 analogs 25 and 26a

aReagents and conditions: (a) RCHO, AcOH, EtOH, 0 °C; (b) NaCNBH3, 0 °C

The inhibitory activity of the analogs was determined against STEP both in the presence and the absence of 1 mM reduced glutathione (GSH) (Table 1).12 GSH is a ubiquitous reducing agent in cells,13 and may interact with the inhibitors because of their polysulfide character. We therefore thought it was prudent to investigate the inhibitor activity under both of these conditions. In the absence of GSH the most potent inhibitor in the series was the simple 7-(trifluoromethyl)-benzopentathiepin 22 (10 ± 1 nM). However, with the absence of the amine substituent, the solubility and thus future utility of 22 is limited. With a benchmark IC50 of 24.6 ± 0.8 nM, TC-2153 remains one of the most potent analogs in this series, along with the other aniline hydrochloride salts 18 (25 ± 7 nM) and 19 (32 ± 3 nM). Trifluoroacetamide derivative 23 also showed good potency (24 ± 1 nM), while the less electron deficient acetamide derivative 24 showed a two-fold decrease in inhibitory activity (49 ± 2 nM). Alkylated anilines 25 and 26, showed a larger drop in potency. Interestingly, the byproducts generated in the synthesis of TC-2153 (10 and 27) also showed activity against STEP though with decreased inhibitory activity.

Table 1.

Inhibition of STEP in vitro in the presence and absence of GSH10

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Entry | Compound | R1 | R2 | IC50 (nM)a,b | IC50′ (μM)a,c |

| 1 | TC-2153 | CF3 | NH3Cl | 24.6 ± 0.8d | 8.8±0.4d |

| 2 | 22 | CF3 | H | 10 ± 1 | 17 ± 2 |

| 3 | 18 | CH3 | NH3Cl | 25 ±7 | 17 ± 1 |

| 4 | 19 | H | NH3Cl | 32 ±3 | 33 ±4 |

| 5 | 23 | CF3 | NHCOCF3 | 24 ±1 | 15 ± 2 |

| 6 | 24 | CF3 | NHAc | 49 ±2 | 24 ± 1 |

| 7 | 25 | CF3 | NHEt | 59 ±9 | >50 |

| 8 | 26 | CF3 | NHBn | 78 ±3 | 27 ±5 |

| 9 | 27 | -- | - | 33 ± 1 | 20 ± 1 |

| 10 | 10 | -- | - | 145 ± 6 | 34 ± 4 |

Assays were performed in duplicate (mean ± S.D.).

Assays contained no GSH.

Assays contained 1 mM GSH.

Assays were performed in quadruplicate (mean ± S.D.); see reference 6.

When GSH was added to the assay mixture, the same trends generally held, with the acylated derivatives performing comparably to the free anilines and the alkylated derivatives having slightly decreased potency. In all cases, there was a decrease in potency by 2–3 orders of magnitude when the GSH reducing agent was present in the assay.

Because the inhibition of STEP by TC-2153 has been shown to be irreversible in the absence of GSH,4 we next determined the second order rate of inactivation (kinact/Ki) for all of the inhibitors under these conditions using the progress-curve method (Table 2).14,15 These results demonstrate that the methyl (18) and unsubstituted (19) derivatives are about three times less potent than trifluoromethyl substituted TC-2153. Additionally, alkylated derivatives 25 and 26 were also less potent, consistent with the IC50 data (Table 1). The Ki values of 23 and 24 indicated that acylation modestly attenuates binding. However, these inhibitors still showed larger kinact/Ki values than TC-2153 because of their much higher kinact values relative to the non-acylated parent structure.

Table 2.

Second order rates of inactivation of TC-2153 analogs13

| Entry | Compound | Kinact/Ki(M-1S-1) | Ki (nM) | Kinact (S-1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | TC-2153 | 153,000 ± 15,000 | 115 ± 10 | 0.0176 ± 0.0007 |

| 2 | 22 | 135,000 ± 18,000 | 109 ± 14 | 0.0147 ± 0.0007 |

| 3 | 18 | 41,000 ± 5,300 | 116 ± 14 | 0.0048 ± 0.0002 |

| 4 | 19 | 52,200 ± 8,000 | 183 ± 25 | 0.0095 ± 0.0006 |

| 5 | 23 | 161,000 ± 26,000 | 235 ± 33 | 0.0378 ± 0.0027 |

| 6 | 24 | 193,000 ± 49,000 | 123 ±29 | 0.0236 ± 0.0022 |

| 7 | 25 | 53,500 ± 8,800 | 230 ± 34 | 0.0123 ± 0.0009 |

| 8 | 26 | 33,200 ± 2,400 | 175 ± 11 | 0.0058 ± 0.0002 |

| 9 | 27 | 138,000 ± 23,000 | 124 ± 19 | 0.0171 ± 0.0011 |

| 10 | 10 | 98,000 ± 20,000 | 210 ± 38 | 0.0205 ± 0.0018 |

Assays were performed in quadruplicate (mean ± S.D.) with no GSH added.

In conclusion, we have prepared and characterized the STEP inhibitory activities of a series of analogs of TC-2153, which has shown promising results in mouse models for AD.4 This study establishes that the electron deficient trifluoromethyl group contributes to potency while the amino group does not, though it is important for aqueous solubility. Other modifications upon the structure are also tolerated. Most importantly, acylation of the aniline is accommodated and could provide a site for introducing reporter groups or functionality for pull down and proteomic applications. Finally, the optimized route for the synthesis of these types of analogs enables their rapid preparation through acylation of a common intermediate.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Support has been provided by the National Institutes of Health (R01-GM054051).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Experimental details including synthetic procedures and analytical characterization of compounds and enzyme assay curves associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at [placeholder].

References and notes

- 1.For a general overview of synaptic plasticity in neuropsychiatric disorders, see the following: Issac JT. J. Physiol. 2009;587:727. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.167742. Palop JJ, Chin J, Mucke L. Nature. 2006;443:768. doi: 10.1038/nature05289.

- 2.Goebel-Goody SM, Baum M, Paspalas CD, Fernandez SM, Carty NC, Kurup P, Lombroso PJ. Pharmacol. Rev. 2012;64:65. doi: 10.1124/pr.110.003053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Zhang YF, Kurup P, Xu J, Carty N, Fernandez S, Nygaard HB, Pittenger C, Greengard P, Strittmatter S, Nairn AC, Lombroso PJ. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2010;107:19014. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1013543107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Zhang YF, Kurup P, Xu J, Anderson G, Greengard P, Nairn AC, Lombroso PJ. J. Neurochem. 2011;119:664. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07450.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xu J, Chatterjee M, Baguley TD, Brouillette J, Kurup P, Ghosh D, Kanyo J, Zhang Y, Seyb K, Ononenyi C, Foscue E, Anderson GM, Gresack J, Cuny GD, Glicksman MA, Greengard P, Lam TT, Tautz L, Nairn AC, Ellman JA, Lombroso PJ. PLoS Biology. 2014;12:e1001923. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.For a prior publication on a different class of STEP inhibitors, see: Baguley TD, Xu H-C, Chatterjee M, Nairn AC, Lombroso PJ, Ellman JA. J. Med. Chem. 2013;56:7636. doi: 10.1021/jm401037h.

- 6.For a general review on phosphatase inhibitors, see: Vintonyak VV, Waldmann H, Rauh D. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2011;19:2145. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.02.047.

- 7.General reviews on cysteine redox and its regulation of PTPs: Parsons ZD, Gates KS. Method. Enzymol. 2013;528:129. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-405881-1.00008-2. Conte ML, Carroll KS. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:26480. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R113.467738.

- 8.Specific examples: Dickinson BC, Chang CJ. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2011;7:504. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.607. Rhee SG. Science. 2006;312:1882. doi: 10.1126/science.1130481. Tonks NK. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006;7:833. doi: 10.1038/nrm2039. Truong TH, Carroll KS. Biochemistry. 2012;51:9954. doi: 10.1021/bi301441e.

- 9.Kulikov AV, Tikhonova MA, Kulikova EA, Khomenko TM, Korchagina DV, Volcho KP, Salakhutdinov NF, Popova NK. Molec. Biol. 2011;45:251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khomenko TM, Korchagina DV, Komarova NI, Volcho KP, Salakhutdinov NF. Lett. Org. Chem. 2011;8:193. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khomenko TM, Tolstikova TG, Bolkunov AV, Dolgikh MP, Pavlova AV, Korchagina DV, Volcho KP, Salakhutdinov NF. Lett. Drug Des. Discov. 2009;6:464. [Google Scholar]

- 12.General protocol for determination of IC50 values: Reaction volumes of 100 μL were used in 96-well plates. 75 μL of water was added to each well, followed by 5 μL of 20× buffer (stock: 1 M imidazole-HCl, pH 7.0, 1 M NaCl, 0.2% Triton-X 100). Five μL of the appropriate inhibitor dilution in DMSO was added, followed by 5 μL of STEP (stock: 0.2 μM, 10 nM in assay). The assay plate was then incubated at 27 °C for 10 min with shaking. The reaction was started by addition of 10 μL of 10× p-nitrophenyl phosphate (pNPP) substrate (stock: 5 mM, 500 μM in assay), and reaction progress was immediately monitored at 405 nm at a temperature of 27 °C. The initial rate data collected was used for determination of IC50 values. For IC50 determination, kinetic values were obtained directly from nonlinear regression of substrate-velocity curves in the presence of various concentrations of inhibitor using one site competition in GraphPad Prism v5.01 scientific graphing software. The KM value of pNPP for STEP under these conditions was determined to be 745 μM, and was used in the kinetic analysis. For the experiments with glutathione reducing agent, 10 μL of glutathione (stock: 10 mM, 1 mM in assay) was added before the inhibitor stocks, and only 65 μL of water was added initially to maintain the 100 μL assay volume. Once the inhibitor stocks were added, the assay plate was allowed to incubate for 10 min at 27 °C with shaking. This was followed by addition of STEP (stock: 1.0 μM, 50 nM in assay) and another 10 min incubation at 27 °C prior to addition of pNPP substrate.

- 13.Meister A, Anderson ME. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1983;52 doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.52.070183.003431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bieth JG. Methods Enzymol. 1995;248:59. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)48007-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.General protocol for determination of kinact/Ki values: Assay wells contained a mixture of the inhibitor (800, 400, 200, 100, 50, 0 nM) and 745 μM of pNPP (KM = 745 μM) in 1× buffer. Aliquots of STEP (final concentration = 10 nM) were added to each well to initiate the assay. Hydrolysis of pNPP was monitored for 30 min at 405 nm. To determine the inhibition parameters, time points for which the control ([I] = 0) was linear were used. A kobs was calculated for each inhibitor concentration via a nonlinear regression of the data according to the equation P=(vi/kobs)(1–e^ (–kobst)) (where P = product formation, vi = initial rate, t = time (s)) using Prism v5.01 (GraphPad). Because kobs varied hyperbolically with [I], nonlinear regression was performed to determine the second-order rate constant, kinact/Ki, using the equation kobs=kinact[I]/([I]+Ki(1+[S]/KM)).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.