Abstract

Background

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is the first biomedical intervention with proven efficacy to reduce human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) acquisition in men who have sex with men (MSM) and transgender women (TGW). Little is known about levels of interest and characteristics of individuals who elect to take PrEP in real-world clinical settings.

Methods

The US PrEP Demonstration Project is a prospective, open-label cohort study assessing PrEP delivery in municipal STD clinics in San Francisco and Miami and a community health center in Washington, DC. HIV-uninfected MSM and TGW seeking sexual health services at participating clinics were assessed for eligibility and offered up to 48 weeks of emtricitabine/tenofovir for PrEP. Predictors of enrollment were assessed using a multivariable Poisson regression model, and characteristics of enrolled participants are described.

Results

Of 1069 clients assessed for participation, 921 were potentially eligible and 557 (60.5%) enrolled. In multivariable analysis, participants from Miami (aRR 1.53; 95% CI 1.33-1.75) or DC (aRR 1.33; 95% CI 1.2-1.47), those who were self-referred (aRR 1.48; 95% CI 1.32-1.66), with prior PrEP awareness (aRR 1.56; 95% CI 1.05-2.33) and those reporting >1 episode of anal sex with an HIV-infected partner in the last 12 months (aRR 1.20; 95% CI 1.09-1.33) were more likely to enroll. Almost all (98%) of enrolled participants were MSM, and at baseline, 63.5% reported condomless receptive anal sex in the prior three months.

Conclusions

Interest in PrEP is high among a diverse population of MSM at risk for HIV infection when offered in STD and community health clinics.

Keywords: Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), HIV Prevention, Men who have sex with men (MSM), sexually transmitted diseases (STD), implementation

In the United States (US), an estimated 50,000 new human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infections occur each year 1, highlighting the urgent need for new prevention strategies. Men who have sex with men (MSM) account for approximately two-thirds of new HIV infections and are the only group in whom HIV incidence has been rising 2. Transgender women (TGW) also have elevated infection rates; over a quarter in the US are HIV-positive 3-5 .

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is the first biomedical intervention with proven efficacy to reduce HIV acquisition in MSM and TGW. iPrEx, a randomized, controlled trial, demonstrated a 44% reduction in HIV incidence among MSM and TGW who received once daily emtricitabine/tenofovir (FTC/TDF), and an estimated >90% efficacy among those with detectable blood drug levels 6,7. Based on compelling data from iPrEx and other PrEP trials 8,9, the US Food and Drug Administration approved FTC/TDF for the prevention of sexually acquired HIV infection in July 2012 10,11. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) published PrEP clinical practice guidelines in May 2014 12.

Modeling studies suggest PrEP could substantially reduce HIV incidence among MSM in the US, and may be cost effective if targeted to the highest risk populations 13-15. However, little is known about levels of interest and characteristics of individuals who elect to take PrEP in clinical settings. An analysis of pharmacy claims found that between January 2012 and September 2013, only 2319 people filled prescriptions for FTC/TDF PrEP in the US and almost half were women 16. Several factors, including perceived low demand for PrEP 17-19, inadequate access to insurance or healthcare 20, lack of provider knowledge or willingness to prescribe PrEP 21-24, and concerns about adherence 25, HIV resistance 26, risk compensation 27, and cost 20,28 may explain why there has not been rapid dissemination of this innovation. Demonstration projects have been recommended to address implementation issues and help determine if appropriate and how best to scale-up PrEP 29,30.

The US PrEP Demonstration Project (The Demo Project) is the first study assessing the feasibility, acceptability and safety of delivering PrEP to MSM and TGW in sexually transmitted disease (STD) clinics and a community health center. In this article, we describe the proportion of potentially eligible participants who elected to enroll in the study (PrEP uptake) and correlates of uptake, and describe baseline demographic and risk characteristics among participants who enrolled.

Methods

Study design, sites and population

The Demo Project is a prospective, longitudinal, open-label cohort study assessing PrEP delivery in municipal STD clinics in San Francisco (SF) and Miami and a community health center in Washington, DC (DC). All three clinics are in metropolitan areas with high HIV incidence 1,31,32 and are experienced in providing sexual health services to at-risk MSM and TGW; the DC clinic also provides primary care services for HIV-uninfected and infected individuals. HIV-uninfected MSM and TGW receiving services or requesting PrEP at the study sites were assessed for participation in The Demo Project. Screening was conducted from September 2012 to November 2013 in SF and Miami and from August 2013 to January 2014 in DC. Enrolled participants were offered up to 48 weeks of FTC/TDF at no charge as part of a comprehensive package of HIV prevention services. This study was sponsored by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and was reviewed and approved by the local institutional review board at each site.

Eligibility criteria

MSM and TGW who were ≥ 18 years of age, able to speak English or Spanish, HIV-negative by self report and who reported any of the following sexual risk criteria in the prior 12 months were eligible to screen for The Demo Project: 1) condomless anal sex with ≥ 2 male or TGW sex partners; 2) ≥ 2 episodes of anal sex with at least one HIV-infected partner; or 3) sex with a male or TGW partner and self-reported history of syphilis, rectal gonorrhea or rectal chlamydia. Participants had to be HIV negative by a rapid HIV antibody and a 4th generation HIV antigen/antibody (Ag/Ab) test at screening and by a rapid HIV antibody test at enrollment, and have a urine dipstick with negative or trace protein and a creatinine clearance ≥ 60 mL/min within 45 days of enrollment. In addition, participants at the SF site had to have a negative pooled HIV RNA at screening. Participants with a positive HBsAg, and those with serious medical or psychiatric co-morbidities, taking nephrotoxic medications, or co-enrolled in other HIV prevention studies or studies of investigational agents or devices were not eligible. Major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder were not exclusionary, unless the participant had active suicidality at the time of screening or was deemed not to have capacity to consent or safely comply with study procedures. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and antihypertensives were not exclusionary. Initially, clients taking non-occupational post-exposure prophylaxis (nPEP) were not eligible to screen or enroll in the study however in May 2013 the protocol was amended such that clients could transition into the study seamlessly from nPEP.

Referral, pre-screening, screening and enrollment

Participants could be referred to the study as a self-referral or clinic-referral. Self-referrals came to the clinic with the expressed interest in seeking PrEP or were referred to the study by their primary care provider. Clinic-referrals presented to the clinic for sexual health services other than PrEP (e.g. HIV/STD testing, STD-related symptoms, nPEP). The process by which clinic referrals initiated pre-screening varied slightly by site, reflecting differences in patient flow and staff capacity. In San Francisco, behavioral eligibility for the Demo project was assessed by a clinician during the clinic visit as part of a standardized risk assessment administered to all MSM and TGW clinic patients. MSM and TGW who met behavioral eligibility criteria for the study were referred to study staff for pre-screening. In Miami, behavioral eligibility for The Demo Project was not assessed by clinic staff. Clinic staff informed MSM and TGW clients about PrEP and The Demo Project and referred all interested patients to the PrEP team for pre-screening. In DC, study staff were embedded in the HIV and STD screening programs that take place within the community health center. Study staff directly approached MSM and TGW clients who were seeking services at these programs and offered them the opportunity to pre-screen for The Demo Project. At all sites, study staff initiated pre-screening by first requesting verbal consent using a standardized script (see Text, Supplemental Digital Content 1).

Participants who were asked for verbal consent to begin the pre-screening process were considered “assessed for participation.” Those who gave verbal consent were considered to have “pre-screened” and were assessed to see if they met any of the three specified behavioral risk criteria. Participants who declined pre-screening were asked verbal consent to complete a refusal questionnaire that included reasons for declining and a limited set of questions regarding demographics, whether they had condomless receptive anal sex in the last 3 months, prior PrEP awareness and HIV risk perception. Participants who did not meet any of the three criteria were deemed behaviorally ineligible, were not asked any additional questions, and were referred back to the clinic for ongoing sexual health services. Participants who were behaviorally eligible completed a short additional questionnaire that included an assessment of sociodemographics, whether they had condomless receptive anal sex in the last 3 months, prior PrEP awareness, HIV risk perception and an assessment for other study eligibility criteria, including major medical co-morbidities (e.g. chronic kidney disease). Participants who declined at any point during pre-screening were asked to complete the refusal questionnaire. Those who were preliminary eligible after completing pre-screening were offered the opportunity to screen for the study.

The screening process began with a review of an electronic presentation providing additional background on PrEP and study goals (see Presentation, Supplemental Digital Content 2), followed by written informed consent and a detailed discussion of the potential risks and benefits of FTC/TDF for PrEP and required study procedures; this process lasted between 20-25 minutes. Participants were informed that study visits would last 1-3 hours (depending on the visit), that they would be asked detailed questions regarding their sexual and drug using behaviors, have phlebotomy and an STD screen every 3 months and be remunerated $25.00 for each scheduled study visit. Participants who signed the written informed consent were considered to have “screened.” Clients could pre-screen or screen for the study multiple times.

Screened participants had a blood draw for HIV, hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), syphilis and creatinine; sample collection for urine, rectal, and pharyngeal gonorrhea and chlamydia; and completed a detailed interviewer-administered questionnaire regarding demographics, sexual and drug use behavior. The enrollment visit was then scheduled 7-45 days after screening. Participants ineligible based on HIV, HBsAg or kidney function results were referred to appropriate services for care. Participants who met all eligibility criteria and remained interested in participation were dispensed their first bottle of FTC/TDF at the enrollment visit and were considered to have “enrolled.” Participants who declined participation during screening or who missed their enrollment visit were asked to complete the refusal questionnaire.

Measures

Diagnostic testing

HIV testing was conducted using both a rapid HIV antibody (Clearview Stat-Pak (SF) or Clearview Complete (Miami, DC)) and a 4th generation HIV Ag/Ab test (Architect; Abbott Diagnostics). In addition, participants in SF were screened for acute HIV using pooled RNA at both screening and enrollment, as is standard practice at the clinic 33. In Miami and DC, an individual HIV RNA assay (Aptima, GenProbe (Miami) or TaqMan V2.0, COBAS (DC)) was conducted at the enrollment visit. Acute HIV was defined as having a negative rapid HIV antibody test and either a positive RNA pool, individual HIV RNA or 4th generation HIV Ag/Ab test. Serologic testing for syphilis was conducted using a venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL) or rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test. Screening for gonorrhea and chlamydia was conducted using nucleic acid amplification tests (Aptima Combo-2; GenProbe).

Sociodemographics, sexual and drug use behaviors

Demographic and risk behavioral data were collected via trained interviewers using standardized questionnaires. Pre-screening included an assessment of sociodemographics, sexual risk behaviors (the three behavioral risk eligibility criteria described above and whether they had condomless receptive anal sex in the last 3 months), prior PrEP awareness and HIV risk perception. Screened participants were asked additional questions regarding sociodemographics (zip code of residence, living situation, employment and insurance status, income, housing/food instability), drug use, and sexual risk behaviors (number of anal sex partners and episodes in the past 3 months, by condom status (with or without a condom), partner HIV serostatus (positive, negative or unknown) and position (insertive or receptive)).

HIV risk perception and PrEP awareness

We measured HIV risk perception using a cognitive assessment of risk (“How likely do you think you are to get HIV in the next year?” (scale 0-100%)) 34; 5% was used as a cut-off based on a post-hoc analysis of a risk perception threshold for predicting uptake. Participants were asked whether and where they had heard about PrEP. Participants who reported having heard of PrEP from someone other than a staff person at the clinic were deemed as having prior PrEP awareness.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize participants assessed, those who were potentially eligible, and those who declined or enrolled. Continuous variables were expressed as means with standard deviation or medians with interquartile ranges, and categorical variables were expressed as percentages. Unadjusted between-group comparisons used chi-square, Fisher's exact, t-, F-, Wilcoxon, and Kruskal-Wallis tests as appropriate.

PrEP uptake was calculated as the number of participants enrolled divided by the number of potentially eligible clients assessed. For participants who pre-screened multiple times, risk covariates and outcome from the last pre-screening attempt were included. We used unadjusted analysis to assess associations of uptake with sociodemographic and risk covariates. Factors associated with PrEP uptake (p<0.05) in bivariate analyses were included in a multivariable Poisson model with robust standard errors 35. Poisson regression was used in order to obtain risk rather than odds-ratios, which are potentially misleading with common outcomes. In checking the final model, we tested for interactions of both study site and referral status with other covariates and assessed linearity of the association of uptake with age, the only continuous covariate. Secular trends in self-referral were assessed using an unadjusted logistic model. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA version 13.1.

Results

Individuals Assessed for Participation

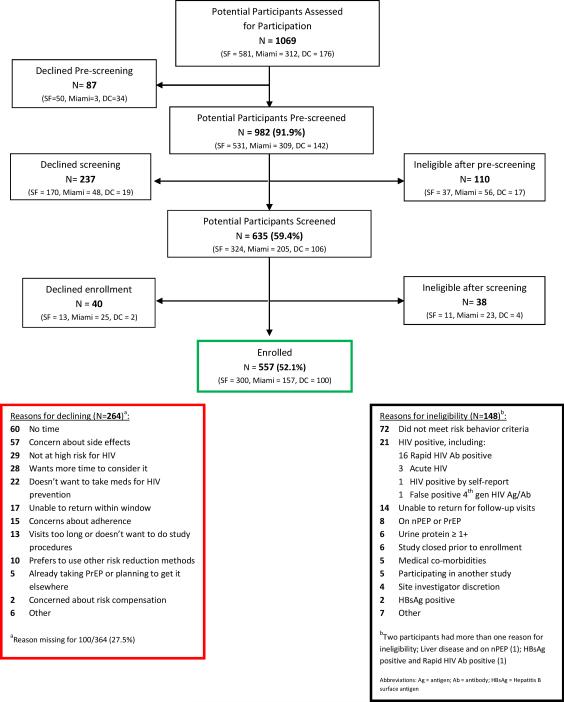

Demographic and risk characteristics of individuals assessed for participation in The Demo Project are summarized by site and referral status in Table 1. Of 1069 clients assessed, 41.9% were white, 36.1% Latino, and 9.2% black (Table 1). Almost all were MSM; only 14 (1.4%) were TGW. Individuals assessed in Miami were younger, more likely to be Latino, had lower education level, were less likely to have heard of PrEP or be self-referred, and reported fewer condomless sex partners or anal sex episodes with an HIV-positive partner compared with those in DC or SF (p<0.05 for all pairwise comparisons). The majority (63%) of individuals assessed were clinic referrals, 39.6% of whom had previously heard of PrEP. Self-referrals were older, more likely to be white, had a higher education level, and higher reported sexual risk behaviors and risk perception compared with clinic-referred participants (all p<0.05). Differences between clinic and self-referrals remained significant after adjustment for site. The proportion of clients who were self-referred increased throughout the study period (from 29.9% in the first three months to 52.6% in the last three months; p<0.0005, test for trend). Screening outcomes and main reasons for ineligibility and declining are shown in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of clients assessed for participation, overall and by site and referral status

| CHARACTERISTIC | OVERALLa (N=1069) | SITEa | REFERRAL STATUSa,b | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SF (N=581) N (%) | Miami (N=312) N (%) | DC (N=176) N (%) | Clinic (N=628) N (%) | Self (N=369) N (%) | ||

| Sitec | ||||||

| SF | 581 (54.3) | 315 (50.2) | 252 (68.3) | |||

| Miami | 312 (29.2) | 216 (34.4) | 46 (12.5) | |||

| DC | 176 (16.5) | 97 (15.5) | 71 (19.3) | |||

| Referral statusc,d | ||||||

| Clinic-referral | 628 (63.0) | 315 (55.6) | 216 (82.4) | 97 (57.7) | ||

| Self-referral | 369 (37.0) | 252 (44.4) | 46 (17.6) | 71 (42.3) | ||

| Agec, d | ||||||

| 18-25 | 228 (23.1) | 107 (19.0) | 91 (35.1) | 30 (18.0) | 172 (27.8) | 56 (15.2) |

| 26-35 | 391 (39.6) | 223 (39.7) | 87 (33.6) | 81 (48.5) | 244 (39.4) | 147 (39.8) |

| 36-45 | 218 (22.1) | 135 (24.0) | 49 (18.9) | 34 (20.4) | 125 (20.2) | 93 (25.2) |

| >45 | 151 (15.3) | 97 (17.3) | 32 (12.4) | 22 (13.2) | 78 (12.6) | 73 (19.8) |

| Gendere | ||||||

| Male | 969 (98.3) | 550 (98.0) | 258 (99.6) | 161 (98.0) | 605 (98.1) | 364 (98.6) |

| Transgender woman | 14 (1.4) | 10 (1.8) | 1 (0.4) | 3 (1.8) | 11 (1.8) | 3 (0.8) |

| Race/Ethnicityc,d | ||||||

| White | 411 (41.9) | 292 (52.2) | 25 (9.7) | 94 (57.7) | 185 (30.2) | 226 (61.4) |

| Latino | 354 (36.1) | 144 (25.8) | 180 (69.5) | 30 (18.4) | 273 (44.5) | 81 (22.0) |

| Black | 90 (9.2) | 22 (3.9) | 44 (17.0) | 24 (14.7) | 72 (11.8) | 18 (4.9) |

| Asian | 57 (5.8) | 47 (8.4) | 3 (1.2) | 7 (4.3) | 42 (6.9) | 15 (4.1) |

| Otherf | 69 (7.0) | 54 (9.7) | 7 (2.7) | 8 (4.9) | 41 (6.7) | 28 (7.6) |

| Education levelc,d | ||||||

| ≤ High school | 181 (18.4) | 88 (15.7) | 77 (29.7) | 16 (9.8) | 128 (20.8) | 53 (14.4) |

| > High school | 803 (81.6) | 474 (84.3) | 182 (70.3) | 147 (90.2) | 487 (79.2) | 316 (85.6) |

| # male condomless anal sex partners, last 12 moc,d | ||||||

| 0-1 | 175 (18.0) | 46 (8.7) | 100 (32.8) | 29 (20.9) | 86 (16.1) | 25 (6.8) |

| 2-5 | 454 (46.8) | 245 (46.5) | 150 (49.2) | 59 (42.5) | 294 (55.0) | 159 (43.1) |

| >5 | 343 (35.2) | 236 (44.8) | 55 (18.0) | 51 (36.7) | 155 (30.0) | 185 (50.1) |

| # episodes anal sex with HIV+ partner, last 12 moc,d | ||||||

| 0-1 | 557 (57.4) | 239 (45.4) | 247 (81.0) | 71 (51.1) | 357 (66.7) | 135 (36.6) |

| 2-5 | 137 (14.1) | 93 (17.6) | 19 (6.2) | 25 (18.0) | 70 (13.1) | 67 (18.2) |

| >5 | 277 (28.5) | 195 (37.0) | 39 (12.8) | 43 (31.0) | 108 (20.2) | 167 (45.3) |

| Condomless receptive anal sex, last 3 moc,d | ||||||

| No | 347 (35.3) | 154 (27.6) | 130 (50.2) | 63 (38.0) | 242 (39.2) | 105 (28.6) |

| Yes | 636 (64.7) | 404 (72.4) | 129 (49.8) | 103 (62.1) | 374 (60.7) | 262 (71.4) |

| Prior PrEP awarenessc,d | ||||||

| No | 408 (41.4) | 170 (30.4) | 171 (66.0) | 67 (40.4) | 373 (60.4) | 35 (9.5) |

| Yesg | 577 (58.6) | 390 (69.6) | 88 (34.0) | 99 (59.6) | 245 (39.6) | 332 (90.5) |

| HIV risk perceptionc,d | ||||||

| ≤ 5% | 241 (25.2) | 132 (24.6) | 56 (21.7) | 53 (32.9) | 176 (29.4) | 65 (18.3) |

| > 5% | 714 (74.8) | 404 (75.4) | 202 (78.3) | 108 (67.1) | 423 (70.6) | 291 (81.7) |

Columns may not sum to total due to missing data for those who were found to be ineligible or who declined PrEP

Referral status missing for 72/1069 assessed clients

p<.05 for comparison by site

p<.05 for comparison by referral status

3 participants reported gender as “other”: “Genderqueer” (1), “all of the above” (1), and “both as a male and a transgender female” (1)

Includes: Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander (6), American Indian or Alaska Native (1), and multi-race (62)

35 self-referred participants had only heard of PrEP from a staff person at the clinic, and thus did not meet the definition of “prior PrEP awareness”

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram

PrEP Uptake and Correlates

Table 2 shows the disposition of assessed individuals overall, and by demographic and risk characteristics. Overall PrEP uptake was 60.5% and varied by referral status, site, age, race/ethnicity, education, prior PrEP awareness, self-perceived risk, and reported risk behaviors (all p<0.05, Table 2). In multivariable analyses, participants from Miami or DC, those who were self-referred, with prior PrEP awareness, and reporting >1 episode of anal sex with an HIV-infected partner in the last 12 months were more likely to enroll, while those of “other” race/ethnicity were less likely to enroll (Table 3). There were no significant interactions between study site or referral status with other covariates (all p>0.05). While participants who declined PrEP had lower reported risk behaviors and a lower median HIV risk perception score (15, IQR 5-50 vs. 30, IQR 10-50), a substantial proportion of those who declined PrEP reported risk factors associated with HIV acquisition: 61.6% reported condomless receptive anal sex in the last 3 months, 27.5% reported >5 condomless anal sex partners and 43.0% self-reported a history in the last 12 months of syphilis, rectal gonorrhea or rectal chlamydia. Only 46 (13.3%) of potentially eligible self-referrals declined participation: 23 were passive refusals (did not return for screening or enrollment and were unresponsive to outreach), 5 did not have time, 5 had concerns about side effects, 5 found another place to access PrEP, 2 had concerns about adherence, 2 said that the study visits were too long or they did not want to do the study procedures, and 4 listed other reasons for declining participation.

Table 2.

PrEP uptake, overall and by selected characteristics

| GROUP | Assesseda N (%) | Potentially Eligiblea,b N (%) | OUTCOME | Percent PrEP uptakec | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Declineda N (%) | Enrolled N (%) | ||||

| Overall | 1069d | 921 | 364 | 557 | 60.5 |

| Sitee | |||||

| SF | 581 (54.4) | 533 (57.9) | 233 (64.0) | 300 (53.9) | 56.3 |

| Miami | 312 (29.2) | 233 (25.3) | 76 (21.0) | 157 (28.2) | 67.4 |

| DC | 176 (16.5) | 155 (16.8) | 55 (15.1) | 100 (18.0) | 64.5 |

| Referral statuse | |||||

| Clinic-referral | 628 (63.0) | 572 (62.4) | 314 (87.2) | 258 (46.3) | 45.1 |

| Self-referral | 369 (37.0) | 345 (37.6) | 46 (12.8) | 299 (53.7) | 86.7 |

| Agee | |||||

| 18-25 | 228 (23.1) | 208 (22.9) | 96 (27.4) | 112 (20.1) | 53.9 |

| 26-35 | 391 (39.6) | 358 (39.4) | 149 (42.5) | 209 (37.5) | 58.4 |

| 36-45 | 218 (22.1) | 202 (22.2) | 68 (19.4) | 134 (24.1) | 66.3 |

| >45 | 151 (15.3) | 140 (15.4) | 38 (10.8) | 102 (18.3) | 72.9 |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 969 (98.3) | 891 (98.6) | 343 (98.3) | 548 (98.4) | 61.5 |

| Transgender woman | 14 (1.4) | 13 (1.4) | 6 (1.7) | 7 (1.3) | 53.9 |

| Race/Ethnicitye | |||||

| White | 411 (41.9) | 383 (42.5) | 117 (33.8) | 266 (47.8) | 69.5 |

| Latino | 354 (36.1) | 327 (36.3) | 135 (39.0) | 192 (34.5) | 58.7 |

| Black | 90 (9.2) | 76 (8.4) | 36 (10.4) | 40 (7.2) | 52.6 |

| Asian | 57 (5.8) | 52 (5.8) | 26 (7.5) | 26 (4.7) | 50.0 |

| Other | 69 (7.0) | 64 (7.1) | 32 (9.3) | 32(5.8) | 50.0 |

| Education levele | |||||

| ≤ High school | 181 (18.4) | 157 (17.4) | 75 (21.6) | 82 (14.7) | 52.2 |

| > High school | 803 (81.6) | 747 (82.6) | 272 (78.4) | 475 (85.3) | 63.6 |

| # male condomless anal sex partners, last 12 moe | |||||

| 0-1 | 175 (18.0) | 97 (11.6) | 37 (13.4) | 60 (10.8) | 61.9 |

| 2-5 | 454 (46.8) | 424 (50.9) | 163 (59.1) | 261 (46.9) | 61.6 |

| >5 | 342 (35.2) | 312 (37.5) | 76 (27.5) | 236 (42.4) | 75.6 |

| # episodes anal sex with HIV+ partner, last 12 moe | |||||

| 0-1 | 557 (57.4) | 443 (53.2) | 188 (68.1) | 255 (45.8) | 57.6 |

| 2-5 | 137 (14.1) | 130 (15.6) | 35 (12.7) | 95 (17.1) | 73.1 |

| >5 | 277 (28.5) | 260 (31.2) | 53 (19.2) | 207 (37.2) | 79.6 |

| Condomless receptive anal sex, last 3 mo | |||||

| No | 347 (35.3) | 316 (35.0) | 133 (38.4) | 183 (32.9) | 57.9 |

| Yes | 636 (64.7) | 587 (65.0) | 213 (61.6) | 374 (67.2) | 63.7 |

| Prior PrEP awarenesse | |||||

| No | 408 (41.4) | 372 (41.1) | 198 (56.9) | 174 (31.2) | 46.8 |

| Yes | 577 (58.6) | 533 (58.9) | 150 (43.1) | 383 (68.8) | 71.9 |

| HIV risk perceptione | |||||

| ≤ 5% | 241 (25.2) | 220 (25.0) | 110 (33.1) | 110 (20.1) | 50.0 |

| > 5% | 714 (74.8) | 659 (75.0) | 222 (66.9) | 437 (79.9) | 66.3 |

Columns may not sum to total due to missing data for those who were found to be ineligible or who declined PrEP

Potentially eligible participants were those NOT found to be ineligible during pre-screening or screening; some potentially eligible participants declined further participation prior to having a complete assessment of eligibility

% Uptake = # Enrolled/# Potentially eligible

37 participants pre-screened twice and 2 participants pre-screened three times. Data were abstracted from the last pre-screening attempt

p<.05 for difference in % uptake

Table 3.

Predictors of PrEP uptake

| CHARACTERISTIC | Bivariate RR (95% CI) | aRR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Site | ||

| SF | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Miami | 1.20 (1.07-1.35) | 1.53 (1.33-1.75) |

| DC | 1.15 (1.0-1.32) | 1.33 (1.2-1.47) |

| Age, per 10 year increase | 1.10 (1.05-1.16) | 1.04 (0.99-1.09) |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| White | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Latino | 0.85 (0.76-0.95) | 0.97 (0.85-1.1) |

| Black | 0.76 (0.61-0.95) | 0.84 (0.68-1.04) |

| Asian | 0.72 (0.54-0.95) | 0.88 (0.68-1.14) |

| Other | 0.72 (0.56-0.93) | 0.82 (0.68-0.99) |

| Education level | ||

| ≤ High school | 1.0 | |

| > High school | 1.22 (1.04-1.43) | 1.09 (0.94-1.26) |

| # male condomless anal sex partners, last 12 mo | ||

| 0-1 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| 2-5 | 1.0 (0.84-1.18) | 1.05 (0.89-1.24) |

| >5 | 1.22 (1.03-1.45) | 1.13 (0.96-1.33) |

| # episodes anal sex with HIV+ partner, last 12 mo | ||

| 0-1 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| 2-5 | 1.27 (1.11-1.45) | 1.17 (1.02-1.33) |

| >5 | 1.38 (1.25-1.53) | 1.22 (1.09-1.36) |

| Referral status | ||

| Clinic-referral | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Self-referral | 1.92 (1.74-2.12) | 1.48 (1.32-1.66) |

| Prior PrEP awareness | ||

| No | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Yes | 2.91 (2.2-3.84) | 1.56 (1.05-2.33) |

| HIV risk perception | ||

| ≤ 5% | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| > 5% | 1.33 (1.15-1.53) | 1.07 (0.95-1.21) |

Participants Enrolled

The mean age of enrolled participants was 35 years; 47.8% were white, 34.5% Latino, 7.2% black, 4.7% Asian and 5.8% other; 98.4% were MSM and 8.5% identified as bisexual. The majority reported working full time (61.9%), 15.9% were unemployed; 34.2% reported an annual income of less than $20,000 and 29.6% of ≥$60,000. About two-thirds had health insurance (62.6%), and 53.0% had a primary care provider. Approximately 4% had participated in a prior PrEP study, 3.1% had used PrEP outside of a study, and 15.1% had a sexual partner taking PrEP (42% of these partners were enrolled in the Demo Project). Almost all participants had tested for HIV in the last year (94.8%). The most commonly reported main reason for enrolling in the study was “to protect myself against HIV” (66.6%), “to help fight the HIV epidemic” (14.9%), and “because my partner has HIV and I want to avoid getting HIV” (10.4%). While only 4.7% reported “to make it safer for me to have sex without condoms” as their main reason for enrolling, 58.9% included it as one of several reasons for enrolling (see Table, Supplemental Digital Content 3).

Baseline sexual behaviors, drug use, and STDs among enrolled participants

Risk characteristics of enrolled participants are shown in Table 4. 58.2% reported poppers, crack, cocaine, methamphetamine or club drug use in the past 3 months. Over half did not have a primary partner while 32% of self-referred and 14% of clinic-referred participants had an HIV-positive partner. The median number of male anal sex partners was 5 (IQR 2, 10) and the median number of episodes of condomless anal sex was 7 (IQR 2, 20), both in the past 3 months. Almost two-thirds reported at least one episode of condomless receptive anal sex, including 23.7% with any HIV-positive partners. Over one-quarter (27.5%) were diagnosed with an STD at baseline; 4.3% with early syphilis and 16.6% with rectal gonorrhea or chlamydia. Higher HIV risk perception was associated with higher reported risk behaviors, including number of condomless anal sex partners and episodes (p for trend <0.0001), and having condomless receptive anal sex with HIV unknown status or HIV-positive partners (p<0.0001).

Table 4.

Drug, sexual risk behaviors and STD prevalence among enrolled participants (N=557)

| Drug and sexual risk behaviors | N (%) |

|---|---|

| ≥ 5 drinks/day when drinking | 64 (11.5) |

| Drug use, past 3 mo. | |

| Poppers or other inhalants | 258 (46.3) |

| Powder cocaine/crack | 112 (20.1) |

| Methamphetamines | 83 (14.9) |

| Club drugsa | 129 (23.2) |

| ED drugsb | 175 (32.1) |

| Marijuana | 244 (43.8) |

| Injected drugs last 3 mo. | 10 (1.8) |

| Has primary partner | |

| Yes – HIV positive | 132 (23.7) |

| Yes – HIV negative | 129 (23.2) |

| Yes – Unsure of HIV status | 6 (1.1) |

| No | 290 (52.1) |

| # male condomless anal sex partners, last 3 mo | |

| 0 | 75 (13.5) |

| 1 | 117 (21.0) |

| 2-5 | 233 (41.8) |

| 6-9 | 59 (10.6) |

| ≥10 | 71 (13.1) |

| # male condomless anal sex episodes, last 3 mo | |

| 0 | 77 (13.8) |

| 1 | 27 (4.9) |

| 2-5 | 130 (23.3) |

| 6-9 | 75 (13.5) |

| ≥10 | 248 (44.5) |

| Condomless anal sex | |

| None | 77 (13.8) |

| Insertive only | 126 (22.6) |

| Any receptive | 354 (63.6) |

| Condomless receptive anal sex, last 3 mo. | |

| None | 203 (36.5) |

| With HIV negative only | 147 (26.4) |

| With unknown serostatus | 75 (13.5) |

| With any HIV positive | 132 (23.7) |

| Any female condomless anal or vaginal sex partners | 12 (2.2) |

| Exchange sex last 3 months | 30 (5.4) |

| Perceived likelihood of getting HIV in next year | |

| <5% | 110 (20.1) |

| 5-25% | 152 (27.8) |

| 26-50% | 196 (35.8) |

| >50% | 89 (16.3) |

| Prevalence of STDs | |

| Early syphilis | 24 (4.3) |

| Primary | 5 (0.9) |

| Secondary | 9 (1.6) |

| Early latent | 10 (1.8) |

| Gonorrhea (any site) | 86 (15.4) |

| Chlamydia (any site) | 75 (13.5) |

| Rectal gonorrhea or chlamydia | 92 (16.6) |

Ecstasy, gamma-hydroxybutyrate (GHB), or ketamine

Recreational use of medications to enhance erectile dysfunction, including sildenafil, vardenafil, and tadalafil

Discussion

Despite early reports of slow PrEP uptake in the US 36-38, we show high levels of interest in PrEP among MSM offered PrEP as part of a comprehensive prevention program in STD clinics and a community health center. Almost half of eligible clinic-referred clients, the majority of whom had never heard of PrEP, and 87% of self-referrals enrolled in The Demo Project. PrEP uptake was high across sites, age groups, race/ethnicities, and levels of education. These findings are consistent with a number of prior surveys of MSM conducted before 39,40 and after 19 the release of iPrEx results indicating high levels of willingness to use PrEP if efficacious and provided at low or no cost 40,41. This suggests prior “slow uptake” may have been due to a lack of PrEP knowledge and availability, and efforts to facilitate both can lead to high uptake of PrEP among at-risk MSM.

Rates of self-referral to the study were high in SF and DC and increased throughout the enrollment period at all three sites. A substantial proportion (15%) of participants reported having a sexual partner on PrEP, with almost half of these enrolled in the Demo Project, suggesting the potential influence of peer referrals in driving PrEP uptake. However, black and Latino MSM, younger individuals, and those with a lower educational level were less likely to self-refer, and very few TGW were assessed for participation. These findings highlight the importance of reaching out to these populations, to increase PrEP awareness and interest, and to ensure that PrEP is available at sites where young MSM of color and TGW seek sexual health services. In adjusted analyses, blacks and Latinos were no less likely to enroll than whites, suggesting PrEP uptake can be high in these individuals when provided information and access to PrEP. Reasons for lower PrEP uptake among those of “other” race/ethnicity are unclear; this was a heterogeneous group and included multi-race individuals.

A substantial number of participants who declined PrEP reported not having enough time for participation. Whether the time required to access PrEP outside of a study would also be a deterrent is unclear, and strategies for optimizing the efficiency and convenience of delivering PrEP are needed. Concern about side effects was also a common reason for declining, a finding reported in prior acceptability surveys 41. These results underscore the importance of accurate community education regarding the safety profile and tolerability of FTC/TDF PrEP when taken by HIV-uninfected individuals 8,9,42. While participants who declined PrEP had lower reported risk behaviors and lower perceived risk of HIV acquisition than those who enrolled, their risk behaviors and self-reported STD history still reflected substantial HIV risk. Risk assessment tools could be used to assist individuals in making more accurate assessments of their HIV risk and selecting from a range of HIV prevention tools, including PrEP 43,44.

Modeling studies suggest that the uptake of PrEP among those at highest risk of HIV will maximize the cost-effectiveness 15,45 and public health impact of PrEP 46. The cohort of participants who enrolled in the Demo Project reported high rates of recreational drug use, condomless receptive anal sex, and had a high prevalence of early syphilis or rectal infections, all factors strongly associated with HIV acquisition 42,47-49. Furthermore, 20 individuals were diagnosed with HIV infection during the screening process, including 3 with acute HIV. These findings show that MSM at high risk for HIV acquisition are interested in PrEP and highlight the role that PrEP programs can play in identifying those with undiagnosed and early HIV infection, as well as those at risk for HIV acquisition who may benefit from PrEP. While interest in PrEP was high among our cohort, additional strategies to increase PrEP uptake and coverage may be required to maximize population level impact 15.

There are several limitations to our study. First, the process by which clients were referred from clinic staff to study staff varied by site and may have led to an overestimate of uptake for clinic-referrals in SF and Miami, where some clients declined prior to assessment by the PrEP team. Second, sociodemographic, risk behavior data and reasons for declining were not available for all participants who declined, and differential patterns in missing data may have biased the results. Third, questionnaires on sexual and drug risk behavior were interview-administered, and may be subject to social desirability bias. Finally, these results may not be generalizable to clients offered PrEP in other clinical settings, without the commitment required of a clinical study, or when there is some cost or other barriers to accessing PrEP clinical services and medication.

Overall, our findings illustrate substantial interest in PrEP among a diverse population of MSM at elevated risk for HIV infection when offered in STD clinics and a community health center, and highlight the role that these clinics can play in expanding PrEP access nationwide. Additional strategies are needed to increase community awareness about PrEP, and engage TGW and young MSM of color in PrEP programs. Additional PrEP Demonstration Projects are underway to evaluate the feasibility, acceptability, and safety of PrEP delivery in a variety of populations 50. As adherence to PrEP is critical to its effectiveness 7, this and other PrEP demonstration projects will evaluate this important PrEP implementation outcome in longitudinal follow-up. Appropriate PrEP uptake among those at highest risk, coupled with high adherence, will help maximize PrEP's public health impact.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

FUNDING

This work was supported by National Institute for Allergies and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) [UM1AI069496]; National Institute for Mental Health (NIMH) [R01MH095628]; and the Miami Center for AIDS Research (CFAR) [P30AI073961] from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). NIAID participated as a partner in protocol development, interpretation of data and gave final approval to submit the manuscript for publication. Study drug for The PrEP Demo Project was provided by Gilead, but Gilead played no role in design or conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; preparation or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Susan Philip has received speaker's honorarium from Gilead. Richard Elion has received research support from Gilead and is on the speakers’ bureau for Gilead.

Footnotes

This study was presented at the 21st Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, March 2014, Boston, MA (abstract #954) and the 9th International Conference on HIV Treatment and Prevention Adherence, June 2014, Miami, FL (abstract #377).

Author Contributions

SC and AL had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. SC, OB, SD, MK and AL conceived and designed the study, oversaw study recruitment and enrollment, assisted with analysis and interpretation of data, and assisted with drafting and revising the manuscript. BP led case report form development and oversaw data management and data quality and assisted with revising the manuscript. EV conducted analyses and interpretation of data and assisted with drafting and revising the manuscript. RE, MC, RB, NT, and YE assisted with study management and supervision and data acquisition and interpretation. DF assisted with instrument development, data analysis, and interpretation, and assisted with drafting and revising the manuscript. WC assisted with protocol development and data interpretation. TM assisted with design and oversight of adherence and risk reduction counseling, and analysis and interpretation of data. SB and SP assisted with data interpretation. All authors edited and approved the final manuscript.

Additional Contributions

We thank the following site coordinators, data managers, pharmacists, counselors and clinicians for their invaluable contributions:

From the San Francisco Department of Public Health: Amy Hilley, MPH; Aaron Hostetler, BA; Amanda Jernstrom, BA; Zoe Lehman, BA; Amelia Herrera, BA; Anthony Sayegh, FNP; Sally Grant, FNP; Tamara Ooms, FNP; Debbie Nguyen, BS; Scott Fields, PharmD. From University of Miami Miller School of Medicine: Yves Jeanty, PhD; Gabriel Cardenas, MPH; Henry Boza, BA; Gregory Tapia, BA; Isabella Rosa-Cunha, MD; Maria Alcaide, MD; Faith Doyle, FNP; Khemraj Hirani, PHD. From Whitman Walker Health: Justin Schmandt, MPH; Tina Celenza, PA-C; Anna Wimpelberg, BA; Gwen Ledford, BA; JJ Locquiao, BA; Adwoa Addai, PharmD. From NIAID: Cherlynn Mathias. We would also like to thank Rivet Amico, PhD, Sarit Golub, PhD and Robert Grant, MD, MPH for their guidance with protocol design and instrument development.

TRIAL REGISTRATION clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT# 01632995

Potential conflicts of interest

No disclosures: SC, EV, OB, SD, BP, DF, TM, NT, RWB, YE, MC, JC, WC, SB, MK, AL.

SP has received research support from Roche Diagnostics, Sera Care Life Sciences, Cepheid Inc., and Melinta, and speaker's honorarium from Gilead.

RE has received research support from Gilead, BMS, Abbvie, ViiV, and Merck, has served on advisory boards for Gilead, BMS, and Viiv, and is on the speakers’ bureau for Gilead, BMS, ViiV, Merck, and Jannsen.

The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services or the City and County of San Francisco, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

SUPPLEMENTAL DIGITAL CONTENT

Supplemental Digital Content 1. Text of standardized script used to obtain verbal consent for pre-screening. doc

Supplemental Digital Content 2. Educational powerpoint about PrEP and The Demo Project. pdf Supplemental Digital Content 3. Table showing reasons for enrolling in The Demo Project. doc

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Estimated HIV Incidence in the United States, 2007-2010. HIV Surveilance Report. 2012;17(4) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prejean J, Song R, Hernandez A, et al. Estimated HIV incidence in the United States, 2006-2009. PLoS One. 2011;6(8):e17502. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clements-Nolle K, Marx R, Guzman R, Katz M. HIV prevalence, risk behaviors, health care use, and mental health status of transgender persons: implications for public health intervention. Am J Public Health. 2001 Jun;91(6):915–921. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.6.915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Edwards JW, Fisher DG, Reynolds GL. Male-to-female transgender and transsexual clients of HIV service programs in Los Angeles County, California. Am J Public Health. 2007 Jun;97(6):1030–1033. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.097717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nemoto T, Operario D, Keatley J, Han L, Soma T. HIV risk behaviors among male-to-female transgender persons of color in San Francisco. Am J Public Health. 2004 Jul;94(7):1193–1199. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.7.1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, et al. Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N Engl J Med. 2010 Dec 30;363(27):2587–2599. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anderson PL, Glidden DV, Liu A, et al. Emtricitabine-tenofovir concentrations and pre-exposure prophylaxis efficacy in men who have sex with men. Sci Transl Med. 2012 Sep 12;4(151):151ra125. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women. N Engl J Med. 2012 Aug 2;367(5):399–410. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1108524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thigpen MC, Kebaabetswe PM, Paxton LA, et al. Antiretroviral preexposure prophylaxis for heterosexual HIV transmission in Botswana. N Engl J Med. 2012 Aug 2;367(5):423–434. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.FDA approves first drug for reducing the risk of sexually acquired HIV infection. US Food and Drug Administration; Jul 16, 2012. 2012. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/newsevents/newsroom/pressannouncements/ucm312210.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holmes D. FDA paves the way for pre-exposure HIV prophylaxis. Lancet. 2012 Jul 28;380(9839):325. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(12)61235-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis for the Prevention of HIV Infection in the United States – 2014, A clinical Practice Guideline. United States Public Health Service. 2014 Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/PrEPguidelines2014.pdf.

- 13.Desai K, Sansom SL, Ackers ML, et al. Modeling the impact of HIV chemoprophylaxis strategies among men who have sex with men in the United States: HIV infections prevented and cost-effectiveness. AIDS. 2008 Sep 12;22(14):1829–1839. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32830e00f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paltiel AD, Freedberg KA, Scott CA, et al. HIV preexposure prophylaxis in the United States: impact on lifetime infection risk, clinical outcomes, and cost-effectiveness. Clin Infect Dis. 2009 Mar 15;48(6):806–815. doi: 10.1086/597095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Juusola JL, Brandeau ML, Owens DK, Bendavid E. The cost-effectiveness of preexposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention in the United States in men who have sex with men. Ann Intern Med. 2012 Apr 17;156(8):541–550. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-156-8-201204170-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mera R, Ng L, Magnuson D, Silva AC, Rawlings K. Presented at: HIV Drug Therapy in the Americas Conference. Rio de Janeiro; Brazil: 2014. Characteristics of Truvada for Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis: Users in the US. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saberi P, Gamarel KE, Neilands TB, Comfort M, Sheon N. Ambiguity, ambivalence, and apprehensions of taking HIV-1 pre-exposure prophylaxis among male couples in San Francisco: a mixed methods study. PLoS One. 2012:e50061. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fuchs J, Sobieszczyk ME, Madenwald T, Grove D, Karuna ST. Intentions to use preexposure prophylaxis among current phase 2B preventative HIV-1 vaccine efficacy trial participants. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;63:259–262. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318296df94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krakower DS, Mimiaga MJ, Rosenberger JG, Novak DS, Mitty JA. Limited Awareness and Low Immediate Uptake of Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis among Men Who Have Sex with Men Using an Internet Social Networking Site. PLoS One. 2012:e33119. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Horberg M, Raymond B. Financial policy issues for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis: cost and access to insurance. Am J Prev Med. 2013 Jan;44(1 Suppl 2):S125–128. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tellalian D, Maznavi K, Bredeek UF, Hardy WD. Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV Infection: Results of a Survey of HIV Healthcare Providers Evaluating Their Knowledge, Attitudes, and Prescribing Practices. AIDS Patient Care and STDS. 2013;27(10):553–559. doi: 10.1089/apc.2013.0173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.White JM, Mimiaga MJ, Krakower DS, Mayer KH. Evolution of Massachusetts physician attitudes, knowledge, and experience regarding the use of antiretrovirals for HIV prevention. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2012 Jul;26(7):395–405. doi: 10.1089/apc.2012.0030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arnold EA, Hazelton P, Lane T, et al. A qualitative study of provider thoughts on implementing pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in clinical settings to prevent HIV infection. PLoS One. 2012;7(7):e40603. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tripathi A, Ogbuanu C, Monger M, Gibson JJ, Duffus WA. Preexposure prophylaxis for HIV infection: healthcare providers' knowledge, perception, and willingness to adopt future implementation in the southern US. South Med J. 2012 Apr;105(4):199–206. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e31824f1a1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van der Straten A, Van Damme L, Haberer JE, Bangsberg DR. Unraveling the divergent results of pre-exposure prophylaxis trials for HIV prevention. AIDS. 2012;26:13–19. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283522272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hurt CB, Eron JJ, Cohen MS. Pre-exposure prophylaxis and antiretroviral resistance: HIV prevention at a cost? . Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53:1265–1270. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Golub SA, Kowalczyk W, Weinberger CL, Parsons JT. Preexposure prophylaxis and predicted condom use among high-risk men who have sex with men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;54:548–555. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181e19a54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Juusola JL, Brandequ ML, Owens DK, Bendavid E. The cost-effectiveness of Preexposure Prophylaxis for HIV Prevention in the United States in Men Who Have Sex With Men. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156:541–550. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-156-8-201204170-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guidance on Pre-Exposure Oral Prophylaxis (PrEP) for Serodiscordant Couples, Men and Transgender Women Who Have Sex with Men at High Risk of HIV: Recommendations for Use in the Context of Demonstration Projects. World Health Organization; Jul, 2012. Available at: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidance_prep/en/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Warren MJ, Bass ES. From efficacy to impact: an advocate's agenda for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis implementation. Am J Prev Med. 2013 Jan;44(1 Suppl 2):S167–170. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.HIV/AIDS Epidemiology Annual Report. San Francisco Department of Public Health; Jun, 2012. 2013. Available at: http://www.sfdph.org/dph/files/reports/RptsHIVAIDS/AnnualReport2012.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention (NCHHSTP) Atlas. National Center for HIV/AIDS; Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/atlas. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pilcher CD, Fiscus SA, Nguyen TQ, et al. Detection of acute infections during HIV testing in North Carolina. N Engl J Med. 2005 May 5;352(18):1873–1883. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa042291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Napper LE, Fisher DG, Reynolds GL. Development of the perceived risk of HIV scale. AIDS Behav. 2012 May;16(4):1075–1083. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0003-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zou G. A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004 Apr 1;159(7):702–706. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rawlings K, Mera R, Pechonkina A, Rooney JF, Peschel T, Cheng A, editors. Status of Truvada (TVD) for HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) in the United States: An Early Drug Utilization Analysis.. Presented at: Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy (ICAAC); Denver, CO.. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Glazek C. Why is no one on the first treatment to prevent HIV? The New Yorker. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tuller D. A Resisted Pill to Prevent HIV. The New York Times; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu A, Kittredge P, Vittinghoff E, Raymond H, Ahrens K. Limited knowledge and use of HIV post- and pre-exposure prophylaxis among gay and bisexual men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;47:241–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mimiaga MJ, Case P, Johnson CV, Safren SA, Mayer K. Preexposure antiretroviral prophylaxis attitudes in high-risk Boston area men who report having sex with men: limited knowledge and experience but potential for increased utilization after education. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;50:77–83. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31818d5a27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Young I, McDaid L. How Acceptable are Antiretrovirals for the Prevention of Sexually Transmitted HIV?: A Review of Research on the Acceptability of Oral Pre-exposure Prophylaxis and Treatment as Prevention. AIDS Behav. 2014 Feb;18(2):195–216. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0560-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, et al. Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N Engl J Med. 2010 Dec 30;363(27):2587–2599. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smith DK, Pals SL, Herbst JH, Shinde S, Carey JW. Development of a clinical screening index predictive of incident HIV infection among men who have sex with men in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012 Aug 1;60(4):421–427. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318256b2f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Celum C, Baeten JM, Hughes JP, et al. Integrated strategies for combination HIV prevention: principles and examples for men who have sex with men in the Americas and heterosexual African populations. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013 Jul;63(Suppl 2):S213–220. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182986f3a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wheelock A, Eisingerich AB, Ananworanich J, et al. Are Thai MSM willing to take PrEP for HIV prevention? An analysis of attitudes, preferences and acceptance. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e54288. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Buchbinder S, Glidden DV, Liu A, et al. Who should be offered HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP)? A secondary analysis of a Phase 3 PrEP efficacy trial in men who have sex with men and transgender women. Lancet. 2014 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70025-8. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bernstein KT, Marcus JL, Nieri G, Philip SS, Klausner JD. Rectal gonorrhea and chlamydia reinfection is associated with increased risk of HIV seroconversion. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010 Apr 1;53(4):537–543. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181c3ef29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pathela P, Braunstein SL, Blank S, Schillinger JA. HIV incidence among men with and those without sexually transmitted rectal infections: estimates from matching against an HIV case registry. Clin Infect Dis. 2013 Oct;57(8):1203–1209. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pathela P. Presented at: 20th International Society for Sexually Transmitted Disease Research (ISSTDR) Vienna, Austria: Jul 14-17, 2013. Population-based HIV incidence among men diagnosed with infectious syphilis,. 2000-2011. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Baeten JM, Haberer JE, Liu AY, Sista N. Preexposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention: where have we been and where are we going? J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013 Jul;63(Suppl 2):S122–129. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182986f69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.