Summary

An acceptable level of oxygen exposure in preterm infants that maximizes efficacy and minimizes harm has yet to be determined. Quantifying oxygen exposure as an area-under-the curve (OAUC) has been predictive of later respiratory symptoms among former low birth weight infants. Here, we test the hypothesis that quantifying OAUC in newborn mice can predict their risk for altered lung development and respiratory viral infections as adults. Newborn mice were exposed to room air or a FiO2 of 100% oxygen for 4 days, 60% oxygen for 8 days, or 40% oxygen for 16 days (same cumulative dose of excess oxygen). At 8 weeks of age, mice were infected intranasally with a non-lethal dose of influenza A virus. Adult mice exposed to 100% oxygen for 4 days or 60% oxygen for 8 days exhibited alveolar simplification and altered elastin deposition compared to siblings birthed into room air, as well as increased inflammation and fibrotic lung disease following viral infection. These changes were not observed in mice exposed to 40% oxygen for 16 days. Our findings in mice support the concept that quantifying OAUC over a currently unspecified threshold can predict human risk for respiratory morbidity later in life.

Keywords: Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia, Chronic Lung Disease, Hyperoxia, Infections: Pneumonia, TB, Viral, Prematurity

Introduction

Despite advances in medical and respiratory support of preterm infants, supplemental oxygen remains a mainstay in the treatment of respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) and later bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD). Due to immature anti-oxidant and immune systems, the preterm lung is particularly sensitive to oxygen-induced oxidative stress, inflammation and injury 1,2. Exposure to high levels of supplemental oxygen, as may be needed in treatment of RDS, can cause BPD characterized by alveolar simplification, pruning of the pulmonary vascular tree and prolonged need for oxygen supplementation, which can itself can aggravate lung injury. The relationship between the dose of supplemental oxygen (fraction of inspired oxygen, FiO2) to cause lung injury, the duration of oxygen therapy (days in oxygen) to treat the injured/healing lung and long-term pulmonary sequelae is poorly understood. One approach to studying this relationship is to calculate cumulative oxygen exposure using an area-under-the-curve (OAUC) analysis 3. In a recent study of 75 very low birth weight infants without BPD (defined as supplemental oxygen < 28 days of age), OAUC was a better predictor of later lung symptoms than was duration of oxygen alone. Infants whose OAUC was in the highest exposure quartile were 2-3 times more likely to experience symptomatic airway dysfunction than infants whose OAUC was in the lowest quartile.

Because experimental manipulation of dose and duration of oxygen exposure is not practical in humans, we established a mouse model that phenotypically recapitulates persistent pulmonary diseases seen in children who were born preterm and exposed to high levels of oxygen. In this model, newborn mice are exposed to a high level of oxygen during normal saccular lung development (postnatal days 0–4), followed by recovery in room air during alveolar development (postnatal days 4–14) and beyond. Young adult (8-12 week old) mice that were exposed to 100% oxygen between postnatal days 0–4 exhibited increased lung compliance attributed in part to alveolar simplification and increased elastin deposition along alveolar walls 4. They also display an altered host response to influenza A virus infection defined by excessive recruitment of leukocytes and elevated expression of monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP)-1 5,6. By post-infection day 10 when the virus has normally cleared and lung injury is resolving, alveolar fibrosis and persistent inflammation was observed in infected siblings exposed to hyperoxia as neonates. These findings suggest 320% cumulative excess oxygen (OAUC320 = 100% - 21% × 4 days) is sufficient to disrupt alveolar development and the normal host response to infection. However, a subsequent study found that exposure to 60% oxygen for 4 days (160% cumulative excess oxygen) caused alveolar simplification without altering the host response to infection 6. Furthermore, 40% oxygen for 4 days did not affect the host response to infection or cause alveolar simplification. This suggested 60% oxygen for 4 days (OAUC160) was sufficient to disrupt lung development but not the host response to infection. But those findings did not distinguish whether this was too low of a dose or the duration of 4 days was too short. By varying the dose and duration of oxygen exposure to match OAUC320, we now test the hypothesis that quantifying neonatal OAUC in newborn mice can predict their risk for altered lung development and the host response to influenza A virus infection as young adults.

Materials and Methods

Exposure of mice to hyperoxia and influenza A virus

Newborn C57BL/6J mice pooled from several litters shortly after delivery were randomly exposed to room air (21%) or a cumulative excess oxygen dose of 320%. Equivalent doses of cumulative oxygen were achieved by exposing mice to 100% oxygen for 4 days, 60% oxygen for 8 days, or 40% oxygen for 16 days 4. The 40% and 60% oxygen concentrations were achieved by mixing 100% oxygen with medical-grade compressed air. Oxygen levels were monitored with a TED-60 oxygen sensor (Teledyne Analytical Instruments, City of Industry, CA). All gases were humidified to 40-70% by passage through de-ionized water-jacketed nafion membrane tubing (Perma Pure, Toms River, NJ). Dams were rotated every 24 hours to limit oxygen toxicity to their lungs and to ensure that all pups were afforded similar nutrition. Following oxygen exposure, mice exposed to excess oxygen were returned to room air. Adult female mice (8-10 weeks of age) exposed to room air or hyperoxia at birth were intranasally infected with a 120 hemagglutinating units of influenza A virus (strain HKx31, H3N2) in 25 μl saline 5. Female mice were used because they consistently show a more robust response to neonatal hyperoxia and infection with influenza A virus than males. Such sex related differences are complex and not fully understood 7. Mice were housed in micro-isolator cages in a specified pathogen-free environment and were provided food and water ad libitum. The University Committee on Animal Resources at the University of Rochester approved the use of mice in this study.

Quantification of immune cells

Airway-derived immune cells were collected by bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) as previously described 6. The total number of immune cells collected from each mouse was enumerated using a TC10 automated cell counter (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Cells from individual mice were transferred to separate microscope slides using a cytological centrifuge and were stained with Diff-Quik. The percentage of neutrophils, macrophages, and lymphocytes were then determined by differential leukocyte counts of at least 200 cells on coded slides by two independent investigators.

Quantification of MCP-1 protein

Levels of MCP-1 in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid were determined with an Quantikine MCP-1 specific sandwich ELISA using an internal reference standard (R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) 6. The lower limit of detection for this assay was 3.9 pg/ml.

Lung histology and immunohistochemistry

Lungs were inflation fixed with 10% neutral-buffered formalin at a constant pressure of 25cm water, embedded in paraffin and sectioned 4,8. Tissue sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin, Hart's elastin stain, Gomori's trichrome stain, or with antibody to α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) 5,6. Immune complexes were detected with a fluorescently labeled secondary antibody before tissue sections were counterstained with 4', 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Stained tissue sections were visualized with a Nikon E-800 fluorescence microscope (Nikon, Melville, NY) and images were captured with a SPOT-RT digital camera (Diagnostic Instruments, Sterling Heights, MI). Mean linear intercept (MLI) were measured from images captured under 10X objective using NIS-Elements AR software (Nikon Instruments) 9. Large airways and vessels were excluded from the analysis.

Sircol assay

Total lung collagen was determined using the Sircol Collagen Assay kit (Biocolor, Belfast, UK) according to the manufacturer's instructions and as previously described 6.

Statistical analysis

A primary outcome was concentration of lung collagen. A study size calculation showed 5 animals per group to be sufficient to detect a 40% difference between study arms assuming a baseline (room air) mean collagen level of 9.5 μg/ml, standard deviation of 1.4 μg/ml and 80% power. The outcomes generated from mice exposed to hyperoxia were compared to those obtained from mice exposed to room air using ANOVA and Barlett's test for equal variances. All values are expressed as means ± SE with p < 0.05 being considered significant.

Results

OAUC320 and greater than 40% FiO2 promotes alveolar simplification in adult mice

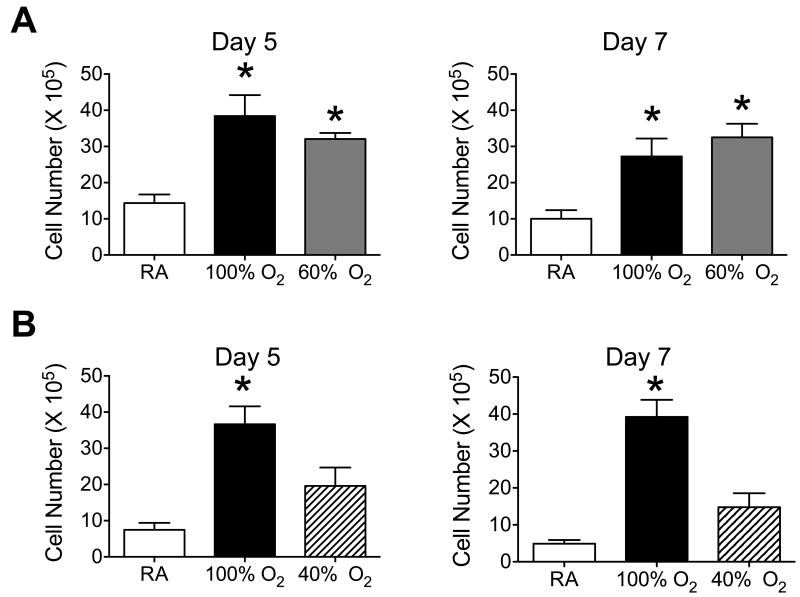

Using 100% oxygen for 4 days as a positive control, two different groups of mice were exposed to an equivalent dose of excess oxygen but over a longer period of time. One group of mice was separately exposed to room air (RA), 100% oxygen for 4 days, or 60% oxygen for 8 days (Figure 1A). A second group of mice was separately exposed to RA, 100% oxygen for 4 days, or 40% oxygen for 16 days. Hence, mice exposed to 100% oxygen for 4 days (100% - 21% in RA × 4 days) received the same excess dose of 320% oxygen as mice exposed to 60% oxygen for 8 days (60% - 21% in RA × 8 days) or 40% oxygen for 16 days (40% - 21% in RA × 16 days). To ensure that differences were observed in all metrics, including the response to influenza A virus infection, it was important that each group of mice included the low (RA) and high (100% oxygen for 4 days) exposures. Since space was limited in the exposure facility, the experimental doses of 60% oxygen for 8 days or 40% oxygen for 16 days were done separately but always with mice exposed to RA and 100% oxygen. Having sibling mice exposed to RA and 100% oxygen was important, especially when evaluating the magnitude of a given host response to infection. Mice exposed to hyperoxia were returned to room air at the end of the exposure and lung pathology was analyzed on postnatal day 56 (8 weeks). Relative to mice exposed to room air, alveolar simplification was readily observed in adult mice exposed to 100% oxygen for 4 days and 60% oxygen for 8 days (Figure 1B). In contrast, alveolar simplification was not seen in adult mice exposed to 40% oxygen for 16 days. The mean linear intercept (distance across the alveolus) was significantly greater in mice exposed to 100% oxygen for 4 days or 60% oxygen for 8 days than mice exposed to room air or 40% oxygen for 16 days (Figure 1C). Abnormal thickened elastin bundles lining alveolar walls were observed in mice exposed to 100% oxygen for 4 days or 60% oxygen for 8 days while predominantly at the tips of secondary crests in mice exposed to room air or 40% oxygen for 16 days (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Alveolar development is disrupted in adult mice exposed to OAUC320 and greater than 40% as neonates. (A) Cartoon depicting exposure of newborn mice to room air (RA) or the same cumulative excess of 320% oxygen by exposure to 100% oxygen for 4 days, 60% oxygen for 8 days, or 40% oxygen for 16 days. (B) Lungs were harvested from adult mice exposed to room air (RA) or the same cumulative OAUC320 using 100%, 60%, or 40% oxygen and sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (upper row) or with Hart's elastin stain (lower row). Arrows point to thickened fibers of elastin bundles lining alveolar walls. Size bar = 100 μm for H & E and 10 μm for elastin stain. (C) The mean linear intercepts (MLI) were determined from 15 random images of an individual mouse lung. Data represents mean ± SE of 7 mice per group (* p < 0.004 relative to room air or 40% oxygen).

OAUC320 and greater than 40% FiO2 alters the host response to influenza A virus infection

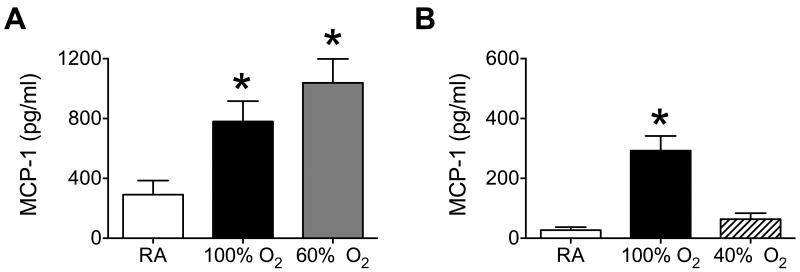

Previous studies showed how exposure to 100% oxygen, but not 60% oxygen, between postnatal days 0-4 altered the host response to influenza A virus infection as defined by excessive recruitment of leukocytes, enhanced production of MCP-1, and lung fibrosis 6. Here, exposure to 100% oxygen between postnatal days 0-4 or 60% oxygen between postnatal days 0-8 significantly enhanced the recruitment of leukocytes to the lung on post-infection days 5 and 7 (Figure 2A). Neonatal hyperoxia significantly increased the proportion of neutrophils and decreased the proportion of macrophages on post-infection day 5, but those differences were not seen by post-infection day 7 (Table 1). In contrast, exposure to 40% oxygen for 16 days did not significantly alter the total number of leukocytes or types of immune cells recruited to lungs of infected mice (Figure 2B, Table 1).

Figure 2.

Cumulative OAUC320 and greater than 40% enhances leukocyte recruitment to lungs of adult mice infected with influenza A virus. Newborn mice were exposed to (A) room air (RA), 100% oxygen for 4 days, or 60% oxygen for 8 days, and (B) RA, 100% oxygen for 4 days or 40% oxygen for 16 days. Oxygen exposed mice were recovered in room air until they were 8-weeks old at which time all mice were infected with influenza A virus intranasally. Leukocytes were harvested on post-infection days 5 and 7 by bronchoalveolar lavage and quantified. Exposure to 60% or 100% oxygen significantly increased the number of leukocytes recruited to infected lungs compared to room air (* p < 0.0005, n = 4-10 mice per group).

Table 1. Differential leukocyte counts in infected mice exposed to hyperoxia.

| Post-infection Day 5 | Post-infection Day 7 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RA | 40% | 60% | 100% | RA | 40% | 60% | 100% | |

|

|

|

|||||||

| Neutrophils, % | 32 ± 1.8 | 36 ± 2.9 | 44 ± 2.8* | 51 ± 2.0* | 16 ± 1.4 | 18 ± 3.1 | 20 ± 4.3 | 22 ± 2.3 |

| Macrophages, % | 58 ± 0.8 | 59 ± 4.2 | 49 ± 3.6* | 43 ± 2.4* | 74 ± 1.9 | 70 ± 2.9 | 68 ± 4.4 | 68 ± 3.3 |

| Lymphocytes, % | 10 ± 1.1 | 5 ± 1.7 | 7 ± 0.8 | 6 ± 1.8 | 10 ± 2.3 | 12 ± 2.1 | 10 ± 2.3 | 10 ± 3.7 |

Leukocytes obtained from bronchoalveolar lavage fluid were centrifuged onto coded slides and stained with Diff Quik. The total number of macrophages, lymphocytes, and neutrophils were quantified in 200 counted cells. Data represents mean ± SD for 4 mice per group.

= P < 0.05 relative to values obtained from room air control mice at that time of infection.

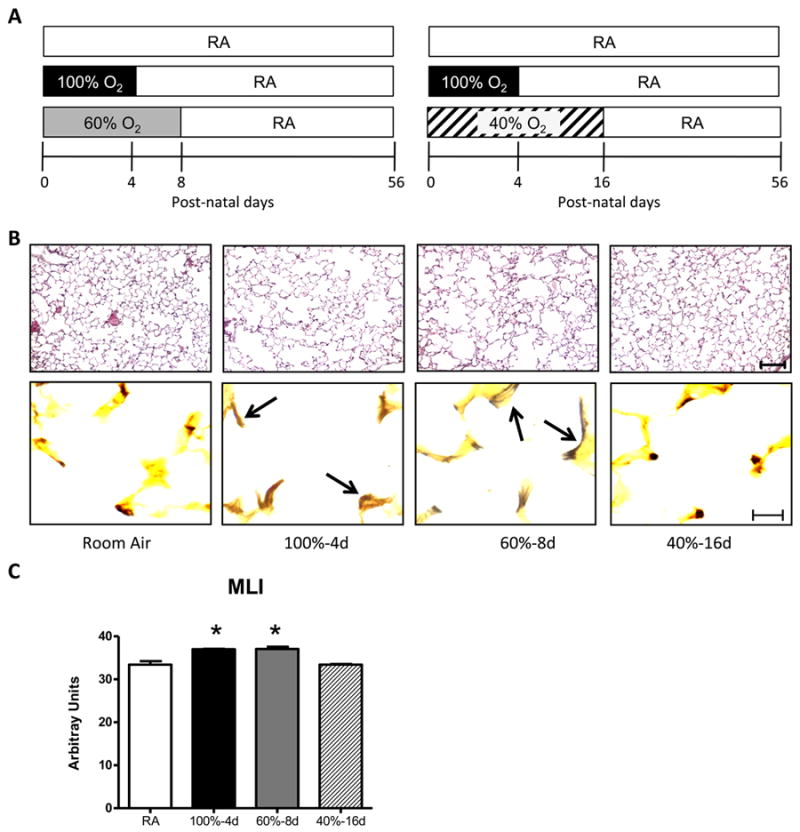

Exposure to 100% oxygen between postnatal days 0-4 selectively enhances the level of MCP-1 but not INF-γ, IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, GM-CSF, or MIP-1α in the airways of adult mice infected with influenza A virus 5. As seen previously, exposure to 100% oxygen for 4 days significantly increased the level of MCP-1 in BAL fluid on post-infection day 5 (Figure 3). Levels of MCP-1 were also significantly greater in infected mice exposed to 60% oxygen for 8 days, but not 40% oxygen for 16 days. The overall reduced amount of MCP-1 shown in Figure 3B compared to Figure 3A reflects severity of response to infection that is often seen when between infections. These differences are likely related to how well mice were infected with influenza A virus on a given day. For this reason, comparisons for any outcome in this study were always made using sibling mice that had been exposed to room air or 100% oxygen at birth.

Figure 3.

Cumulative OAUC320 and greater than 40% enhances the production of monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP)-1 in adult mice infected with influenza A virus. Newborn mice were exposed to (A) room air (RA), 100% oxygen for 4 days, or 60% oxygen for 8 days, and (B) RA, 100% oxygen for 4 days, or 40% oxygen for 16 days. Oxygen exposed mice were recovered in room air until they were 8-weeks old at which time all mice were infected with influenza A virus intranasally. Lungs were extensively lavaged on post-infection day 5 and levels of MCP-1 quantified by ELISA. Exposure to 60% or 100% oxygen significantly increased the levels of MCP-1 present in BAL fluid of infected mice compared to room air (* p < 0.0002, n = 4-6 mice per group).

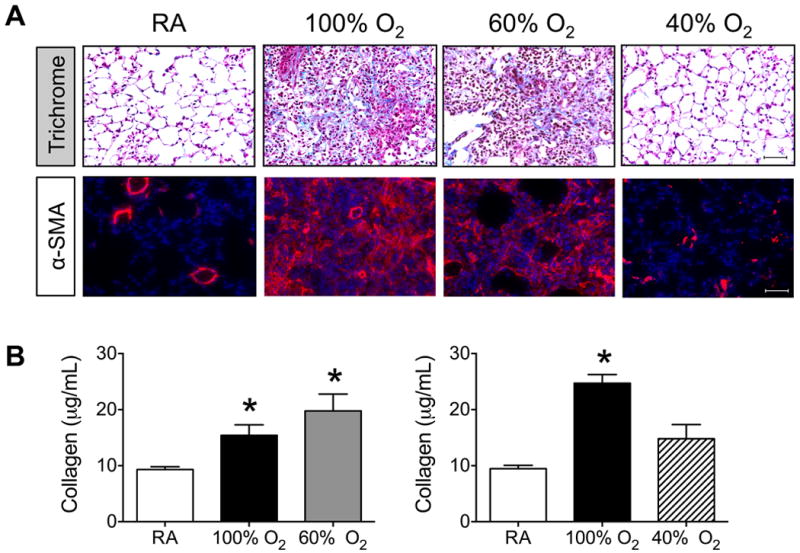

OAUC320 and greater than 40% FiO2 promotes fibrotic repair following influenza A virus infection

By post-infection day 14, pulmonary fibrosis is observed in adult mice exposed to 100% oxygen but not in siblings birthed into room air 5. In the present study, trichrome staining revealed increased collagen deposition in lung tissues harvested from infected mice exposed to 100% or 60% oxygen, but not to 40% oxygen or room air (Figure 4A). These regions of lung tissue also stained positive for α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), a marker of activated myofibroblasts. Positive α-SMA staining shown in mice exposed to room air or 40% oxygen represents normal expression in muscle surrounding large arteries. Consistent with the increased fibrotic staining, total soluble collagen was significantly elevated in lungs of infected mice exposed to 100% or 60% oxygen as neonates (Figure 4B). Increased collagen was not observed in infected mice exposed to 40% oxygen as neonates.

Figure 4.

Cumulative OAUC320 and greater than 40% is sufficient to promote fibrosis in lungs of mice infected with influenza A virus. Newborn mice were exposed to room air (RA), 100% oxygen for 4 days, 60% oxygen for 8 days, or 40% oxygen for 16 days. Oxygen exposed mice were recovered in room air until they were 8-weeks old at which time all mice were infected with influenza A virus intranasally. (A) Lungs were harvested post-infection day 14 and sections stained with trichrome or antibody to α-smooth muscle actin. Size bar = 50 μm. (B) Total amount of soluble collagen present in lungs on post-infection day 14 was quantified and graphed. Exposure to 60% or 100% oxygen significantly increased the amount of collagen present in infected lungs compared to room air (* p < 0.003, n = 5-8 mice per group).

Although the study was not powered to assess differences in survival across all four doses of oxygen, fibrotic lung disease was observed in groups of mice that had reduced survival. By post-infection day 14, survival of mice exposed to 100% oxygen or 60% oxygen was respectively 68% (17/25 mice) and 50% (5/10 mice). In contrast, survival of infected mice exposed to room air or 40% oxygen was respectively 84% (16/19 mice) and 85% (6/7 mice).

Discussion

Using a prospective cohort of 75 very low birth weight infants without BPD, we previously reported that quantifying OAUC in the first 72 hours predicts risk for respiratory medication and health service use in the first year of life 3. Here, we experimentally confirm the concept that quantifying neonatal OAUC can be used to predict adult risk for alveolar simplification and altered host response to influenza A virus infection using a neonatal mouse model of oxygen exposure. Our study identified in mice a threshold of oxygen dose and duration above which lung inflammation, susceptibility to viral induced lung injury, and altered repair from injury was noted and below which lung structure was similar to lung not exposed to supplemental oxygen. In this research paradigm, OAUC ≥ 320 and FiO2 > 40% caused significant alveolar simplification (increased mean linear intercept, thickened elastin bundles lining alveolar walls) and an abnormal response to infection with influenza A characterized by greater number of inflammatory cells, elevated levels of collagen, and fibrosis. This is the first study, to our knowledge, that experimentally predicted risk for respiratory morbidity based upon some quantifiable amount of earlier oxygen exposure. Quantifying OAUC may therefore be a useful predictor of oxygen-associated risk to the long-term health of preterm infants.

Our findings confirms and extends previous findings evaluating how different doses of oxygen for 4 days affects alveolar development in mice 4. In this earlier study, alveolar simplification, altered elastin deposition, and increased functional lung compliance was seen in adult mice exposed to 60%, 80%, and 100% oxygen between postnatal days 0 - 4. While increased lung compliance is often attributed to alveolar simplification, experimental modeling studies suggest elastin bundles lining alveolar walls may also contribute 10. Moreover, equivalent changes in these metrics were seen in mice exposed to 60% and 80% oxygen, with greater changes seen in mice exposed to 100% oxygen. This implies two different thresholds of excess oxygen affect lung development, with 60% and 80% oxygen (OAUC160-240) being one threshold and 100% oxygen (OAUC320) being the second. Although alveolar simplification was seen with an OAUC160-240, the host response to influenza A virus infection was not significantly different 6. In other words, exposure to 60% or 80% oxygen between postnatal days 0–4 did not cause excessive recruitment of inflammatory cells, enhanced production of MCP-1, or fibrotic lung disease following infection with influenza A virus. However, an altered inflammatory and repair response to infection was observed in the current study when newborn mice were exposed to 60% oxygen for 8 days (OAUC320). This implies the dose of 60% oxygen is sufficient to alter the inflammatory response provided the duration was long enough to exceed OAUC160. Duration of oxygen exposure is therefore important for predicting long-term risk of respiratory morbidity.

Our study also identified a lower dose of oxygen that did not alter mouse lung development or the host response to infection. Exposure to 40% oxygen for 16 days, a similar OAUC320 obtained by exposing mice to 100% oxygen for 4 days or 60% oxygen for 8 days was not sufficient to cause detectable alveolar simplification or differences in the host response to influenza A virus infection within the limits of the power of our study. While it is possible that a larger study with greater power might identify a lower dose and duration of FiO2 that disturbs lung development and response to infection, we suspect that a threshold of oxygen exposure exists below which the lung is not affected. For example, it seems unlikely that a 1% increase in oxygen exposure for 320 days would cause the same respiratory morbidity as 100% oxygen for 4 days (same OAUC320).

The cumulative dose that alters lung development and function, as well as the lower threshold below which there is no effect is also likely to vary according to specific developmental windows. The current study evaluated adult risk for respiratory viral infection in mice against a cumulative dose of oxygen provided to the newborn lung, which is mature enough to breathe 21% oxygen without harm. In contrast, the fetal lung is exposed to amniotic fluid whose oxygen content in humans is ∼11mm Hg (or less than 1% oxygen) 11. Arterial pO2 levels in the adult human lung are 100mm Hg versus 30mm Hg in the fetus. Hence, the threshold for oxygen toxicity is likely to be lower in a fetal than a newborn lung. The cumulative dose of oxygen toxicity and lower threshold values may also vary during fetal development because antioxidant defenses mature as the lung prepares to breathe air at birth 12. In fact, preterm human lungs are often oxidatively stressed because of a deficiency in anti-oxidant defenses 13,14. After birth, mortality of a newborn exposed to a specific amount of oxygen is significantly lower than an adult exposed to the same cumulative dose 15. Hence, fetal, newborn, and adult define 3 different developmental windows that function under different amounts of oxygen. When considering how the current findings in mice translate to human disease, it is also important to remember that mice develop significantly faster than humans. If one assumes that young or adolescent mice are 4-5 weeks old, than exposing mice to 4, 8, and 16 days of hyperoxia reflect months to years of exposure in humans. So, while the current findings support the concept of defining oxygen toxicity as a cumulative dose, defining a specific cumulative dose above a lower threshold will require sophisticated assessment of oxygen sensitivities during specific developmental windows whose length varies tremendously among different species. Once those values are determined in animals and humans, the cumulative dose concept may help inform changes to development of the lung and other organs, and predict risk during treatment.

The scientific literature is replete with studies showing how different doses, duration, and timing of hyperoxia disrupt lung development in rodents (for review see 16). So, it is difficult to interpret the toxic effects of oxygen in studies that use different doses, durations, and altitude of oxygen. This becomes more complex when one considers that the response to oxygen can vary by sex and strain of the animal, some of which are genetically modified to study the role of specific molecular pathways 17,18. For instance, interleukin-1 receptor antagonist reduced oxygen-dependent lung inflammation and partially preserved lung development of newborn mice exposed to 65% oxygen for 28 days 19. Interestingly, it did not preserve development of mice exposed to 85% oxygen. The authors concluded that this supports the idea that the amount of oxygen delivered to preterm infants should be limited to the lowest possible amount. While that is true, mice were also exposed to an OAUC1820, which may simply have caused too much oxygen toxicity to show a significant anti-inflammatory benefit. Comparing experimental outcomes against OAUC may therefore help clarify and normalize the data between seemingly different experimental protocols and findings. It may also prove useful for predicting risk for other oxygen-mediated long-term morbidities, including changes in cognition and behavior, agerelated cardiovascular disease, and poor growth 20-23.

Although the current study evaluated the effects of oxygen supplementation on term mice, the lung is in a saccular phase of development much like that of most extremely low birth weight infants 24. Such preterm infants frequently receive oxygen therapy as part of their respiratory care even though its prolonged use can cause oxidative stress and damage to the developing lung and other oxidant sensitive organs 25. The pattern of oxygen usage in the clinical care of preterm infants has changed with the advent of surfactant replacement therapy and increased survival of extremely preterm infants. Whereas very high levels of supplemental oxygen for sustained periods of time were necessary to treat RDS prior to the availability of exogenous surfactant, clinical use of oxygen today is characterized by use of lower FiO2 over long periods of time in extremely preterm infants. We speculate that this change, along with the therapeutic use of milder ventilation strategies, exogenous surfactant therapies, diuretics, improved parenteral nutrition, etc., has contributed to the evolution from “old” BPD, characterized by severe airway injury and lung fibrosis, to “new” BPD in which airway injury and fibrosis are less common and arrested alveolar development is more common. We further speculate that respiratory support strategies that maintain levels of supplemental oxygen below the threshold for lung injury or medical strategies that buffer the lung against oxidative injury will further reduce pulmonary morbidity in preterm infants. For instance, children born preterm and treated with recombinant CuZn-superoxide dismutase (SOD) showed reduced need for medical care in their first year of life as well as decreased risk of ROP 26,27 even though treatment did not reduce the incidence of BPD.

In summary, we have demonstrated for the first time that the host response to viral infection in mice can be disrupted by OAUC320, provided FiO2 >40%, and that defining OAUC may allow us to retrospectively evaluate animal studies that do not have codified exposure protocols. Considering that the development of human and mouse lungs is remarkably similar, and that much of what is currently understood about human lung development has arisen from studies in rodents, our findings support the hypothesis that OAUC as defined in human newborn exposures, may be an appropriate way to predict respiratory symptoms and the need for clinical care later in life.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Patricia Chess, M.D. for her insightful comments during the course of these studies and for critiquing this paper. We also thank Ronnie Guillet, M.D., Ph.D. for suggesting we expose mice to 40% oxygen for 16 days.

Statement of financial support: This work was funded in part by March of Dimes grant 06-FY08-264; National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants HL-067392, HL-091968, HL-097141 (M.A. O'Reilly). NIH Training Grant HD-057821 and Institutional Bradford Scholar Award grant supported E.T. Maduekwe. NIH Training Grants ES-07026 and HL-66988 supported B.W. Buczynski. NIH Center Grant ES-01247 supported the animal inhalation facility and tissue-processing core.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None

References

- 1.Smith CV, Hansen TN, Martin NE, McMicken HW, Elliott SJ. Oxidant stress responses in premature infants during exposure to hyperoxia. Pediatric research. 1993;34(3):360–365. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199309000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davis JM, Auten RL. Maturation of the antioxidant system and the effects on preterm birth. Seminars in fetal & neonatal medicine. 2010;15(4):191–195. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stevens TP, Dylag A, Panthagani I, Pryhuber G, Halterman J. Effect of cumulative oxygen exposure on respiratory symptoms during infancy among VLBW infants without bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2010;45(4):371–379. doi: 10.1002/ppul.21199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yee M, Chess PR, McGrath-Morrow SA, Wang Z, Gelein R, Zhou R, Dean DA, Notter RH, O'Reilly MA. Neonatal oxygen adversely affects lung function in adult mice without altering surfactant composition or activity. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2009;297(4):L641–649. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00023.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O'Reilly MA, Marr SH, Yee M, McGrath-Morrow SA, Lawrence BP. Neonatal hyperoxia enhances the inflammatory response in adult mice infected with influenza A virus. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177(10):1103–1110. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200712-1839OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buczynski BW, Yee M, Paige Lawrence B, O'Reilly MA. Lung development and the host response to influenza A virus are altered by different doses of neonatal oxygen in mice. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2012;302(10):L1078–1087. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00026.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oertelt-Prigione S. The influence of sex and gender on the immune response. Autoimmunity reviews. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2011.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yee M, Vitiello PF, Roper JM, Staversky RJ, Wright TW, McGrath-Morrow SA, Maniscalco WM, Finkelstein JN, O'Reilly MA. Type II epithelial cells are critical target for hyperoxia-mediated impairment of postnatal lung development. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;291(5):L1101–1111. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00126.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McGrath-Morrow SA, Cho C, Soutiere S, Mitzner W, Tuder R. The effect of neonatal hyperoxia on the lung of p21Waf1/Cip1/Sdi1-deficient mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2004;30(5):635–640. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2003-0049OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bates JH, Davis GS, Majumdar A, Butnor KJ, Suki B. Linking parenchymal disease progression to changes in lung mechanical function by percolation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176(6):617–623. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200611-1739OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sjostedt S, Rooth G, Caligara F. The oxygen tension of the amniotic fluid. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 1958;76(6):1226–1230. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(16)36937-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frank L. Developmental aspects of experimental pulmonary oxygen toxicity. Free Radic Biol Med. 1991;11(5):463–494. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(91)90062-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gladstone IM, Jr, Levine RL. Oxidation of proteins in neonatal lungs. Pediatrics. 1994;93(5):764–768. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moison RM, Palinckx JJ, Roest M, Houdkamp E, Berger HM. Induction of lipid peroxidation of pulmonary surfactant by plasma of preterm babies. Lancet. 1993;341(8837):79–82. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)92557-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jobe AH, Kallapur SG. Long term consequences of oxygen therapy in the neonatal period. Seminars in fetal & neonatal medicine. 2010;15(4):230–235. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2010.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buczynski BW, Maduekwe ET, O'Reilly MA. The role of hyperoxia in the pathogenesis of experimental BPD. Seminars in perinatology. 2013;37(2):69–78. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2013.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnston CJ, Stripp BR, Piedbeouf B, Wright TW, Mango GW, Reed CK, Finkelstein JN. Inflammatory and epithelial responses in mouse strains that differ in sensitivity to hyperoxic injury. Experimental Lung Research. 1998;24(2):189–202. doi: 10.3109/01902149809099582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tryka AF, Witschi H, Gosslee DG, McArthur AH, Clapp NK. Patterns of cell proliferation during recovery from oxygen injury. Species differences The American review of respiratory disease. 1986;133(6):1055–1059. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1986.133.6.1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nold MF, Mangan NE, Rudloff I, Cho SX, Shariatian N, Samarasinghe TD, Skuza EM, Pedersen J, Veldman A, Berger PJ, Nold-Petry CA. Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist prevents murine bronchopulmonary dysplasia induced by perinatal inflammation and hyperoxia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(35):14384–14389. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1306859110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Doyle LW, Anderson PJ. Adult outcome of extremely preterm infants. Pediatrics. 2010;126(2):342–351. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Euser AM, de Wit CC, Finken MJ, Rijken M, Wit JM. Growth of preterm born children. Hormone research. 2008;70(6):319–328. doi: 10.1159/000161862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khwaja O, Volpe JJ. Pathogenesis of cerebral white matter injury of prematurity. Archives of disease in childhood Fetal and neonatal edition. 2008;93(2):F153–161. doi: 10.1136/adc.2006.108837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Doyle LW, Faber B, Callanan C, Morley R. Blood pressure in late adolescence and very low birth weight. Pediatrics. 2003;111(2):252–257. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.2.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maeda Y, Dave V, Whitsett JA. Transcriptional control of lung morphogenesis. Physiol Rev. 2007;87(1):219–244. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00028.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Finer N, Leone T. Oxygen saturation monitoring for the preterm infant: the evidence basis for current practice. Pediatric research. 2009;65(4):375–380. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e318199386a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parad RB, Allred EN, Rosenfeld WN, Davis JM. Reduction of retinopathy of prematurity in extremely low gestational age newborns treated with recombinant human Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase. Neonatology. 2012;102(2):139–144. doi: 10.1159/000336639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davis JM, Parad RB, Michele T, Allred E, Price A, Rosenfeld W. Pulmonary outcome at 1 year corrected age in premature infants treated at birth with recombinant human CuZn superoxide dismutase. Pediatrics. 2003;111(3):469–476. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.3.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]