Abstract

Purpose

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) established provisions intended to increase access to affordable health insurance and thus increase access to medical care and long-term surveillance for populations with pre-existing conditions. However, childhood cancer survivors' coverage priorities and familiarity with the ACA are unknown.

Methods

Between May 2011 and April 2012, we surveyed a randomly selected, age-stratified sample of 698 survivors and 210 siblings from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study.

Results

Overall, 89.8% of survivors and 92.1% of siblings were insured. Many features of insurance coverage that survivors considered “very important” are addressed by the ACA, including increased availability of primary care (94.6%), no waiting period before coverage initiation (79.0%), and affordable premiums (88.1%). Survivors were more likely than siblings to deem primary care physician coverage and choice, protections from costs due to pre-existing conditions, and no start-up period as “very important” (P < .05 for all). Only 27.3% of survivors and 26.2% of siblings reported familiarity with the ACA (12.1% of uninsured v 29.0% of insured survivors; odds ratio, 2.86; 95% CI, 1.28 to 6.36). Only 21.3% of survivors and 18.9% of siblings believed the ACA would make it more likely that they would get quality coverage. Survivors' and siblings' concerns about the ACA included increased costs, decreased access to and quality of care, and negative impact on employers and employees.

Conclusion

Although survivors' coverage preferences match many ACA provisions, survivors, particularly uninsured survivors, were not familiar with the ACA. Education and assistance, perhaps through cancer survivor navigation, are critically needed to ensure that survivors access coverage and benefits.

INTRODUCTION

Advancements in cancer therapy and supportive care have led to a growing population of childhood cancer survivors.1 These survivors are at elevated lifetime risk for treatment-related late effects,2 including early mortality,3 subsequent neoplasms,4–6 cardiac complications,7–10 reproductive difficulties,11 cognitive deficits,12,13 liver dysfunction, and other physical14,15 and psychosocial sequelae.16–19 However, the full spectrum of late effects is still relatively unknown, and late effects often do not emerge until several decades after treatment.20–23 Thus, ongoing medical treatment and surveillance, with access to quality health care, are critical for this population. However, previous research, conducted in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS), found that adult survivors of childhood cancer, compared with siblings, had lower rates of health insurance coverage and more difficulties obtaining coverage.24 In addition, adult survivors of childhood cancer were less likely than siblings to be employed, be married, and have a high household income.25–27

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA)28 was signed into law in 2010 and is intended to increase access to affordable, quality health care, including promoting care for populations with pre-existing conditions, such as childhood cancer survivors. At the 2014 closeout of the initial ACA enrollment period in March 2014, 9.5 million uninsured people in the United States had gained coverage.29 The advent of this legislation is timely, because the reality of high copayments, high deductibles, and the recent declines in access to, and increased costs of, employer-sponsored insurance often leaves individuals financially encumbered.30–32 Specific provisions were enacted in 2010 that could benefit childhood cancer survivors, including high-risk insurance pools for those with pre-existing conditions, expansion of insurance coverage to dependents up to age 26 years, Medicaid expansion, and regulations specifying essential health benefits, mandatory primary care visits, and preventive care coverage requirements, including annual checkups and cancer screenings.33

Because the extent of childhood cancer survivors' understanding of the ACA and coverage preferences is largely unknown, we surveyed a subset of survivors and siblings from the CCSS to examine familiarity with the ACA and other health insurance–related legislation before full implementation, concerns and hopes for the ACA, and priorities of insurance coverage.

METHODS

Design

Between May 2011 and April 2012, we performed a single, cross-sectional survey of a randomly selected, age-stratified sample of CCSS participants and a sibling comparison population. All procedures were approved by the institutional review boards of St Jude Children's Research Hospital and the Massachusetts General Hospital/Partners HealthCare.

Participants

The CCSS is a multi-institutional retrospective cohort study with longitudinal follow-up that was initiated in 1994 to track the health outcomes of adult survivors of childhood cancer and compares the results with those of siblings. Eligible survivors were initially diagnosed with cancer between 1970 and 1986, were younger than 21 years old at diagnosis, and survived ≥ 5 years from diagnosis. The CCSS includes survivors of leukemia, lymphoma, CNS malignancy, Wilms tumor, neuroblastoma, soft tissue sarcoma, and bone cancers. The original cohort had 14,357 survivors and a cohort of randomly selected nearest-age siblings (n = 4,023).34–36 Participants were identified from the original cohort's 25 participating centers in the United States.

Data Collection

For the current study, 1,101 survivors and 360 siblings were randomly selected from three age strata (< 30, 30 to 39, ≥ 40 years). Surveys were mailed to selected participants and were completed either on mailed paper versions or on the Internet; instructions indicated that the survey would take approximately 15 to 20 minutes to complete. The final sample (Fig 1) included 698 completed survivor surveys and 210 sibling surveys. The survivor response rate was 63.4% (698 participants of 1,101 selected), and the sibling response rate was 58.3% (210 participants of 360 selected). The participation rate, which differs from the response rate in that known ineligibles (ie, deceased, no known telephone number or address) are removed from the denominator, was 71.4% for survivors (698 participants of 978 known eligibles) and 64.4% for siblings (210 participants of 326 known eligibles).

Fig 1.

CONSORT diagram.

Measures

Survey development was informed by an initial qualitative study37 and by national surveys38–42; surveys were cognitively tested with adult childhood cancer survivors treated at Massachusetts General Hospital. Based on responses to the first survey question, “Do you currently have health insurance that covers doctor and hospital care?” participants were directed to complete either an insured or uninsured version of the survey (https://ccss.stjude.org/documents/original-cohort-questionnaires). Current marital status, employment status, household income, and insurance characteristics were assessed. Data on other sociodemographic, cancer-related, and treatment-related factors were determined from CCSS baseline and follow-up surveys. The incidence of chronic health conditions was obtained from the most recent follow-up survey.

To provide context for levels of ACA familiarity endorsement, we queried participants about existing health insurance–related laws (“Please rate how familiar you are with the health insurance–related benefits and protections that will be available under the new health care reform law.”). Participants' familiarity with the ACA, Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), Family Medical Leave Act (FMLA), and Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (COBRA) was assessed on a 4-point scale from “very familiar” to “not at all familiar”; responses were subsequently dichotomized as “very/somewhat familiar” versus “not too/not at all familiar.” Survey items queried participants' perceived likelihood of obtaining quality insurance coverage through the ACA (“more likely,” “no change,” “less likely,” or “don't know”), hopefulness about the ACA's benefits/protections (“yes,” “no,” or “don't know”), and concerns about the ACA's benefits/protections (“yes,” “no,” or “don't know”). Participants rated, on a 4-point scale, the importance of insurance coverage, features, and costs; responses were subsequently dichotomized as “very important” versus “somewhat/not at all important.” Two write-in questions queried participants about their concerns and hopes for the protections and benefits of the ACA.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed in Stata version 12 (Stata, College Station, TX), incorporating weighting to account for the stratified sampling design so that results were representative of the age distribution in the CCSS cohort. All P values are two-sided and considered significant if P < .05. Survivors and siblings were compared on sociodemographic and insurance characteristics, familiarity with the ACA, perceptions of the ACA, and importance of plan coverage, features, and costs using t tests and χ2 analyses. Among survivors only, unadjusted analyses and multivariable logistic regression models were run to determine the effect of insurance status on familiarity with health-related legislation and the importance of health plan coverage, features, and cost, adjusting for age, sex, marital status, and presence of any chronic health condition. Content analyses were performed on participants' write-in responses to their concerns and hopes for the ACA by two coders (M.F. and E.R.P.). Major themes were identified, compared, and contrasted between survivors and siblings and insured and uninsured participants.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

Over half of survivors and siblings were female, and 93% identified as white (Table 1). The average time since diagnosis was 30.3 years (standard deviation, 4.6 years). The most common cancer diagnosis was leukemia (35.0%). Consistent with previous CCSS research,25–27 when compared with siblings, survivors were less likely to be married (73.6% v 61.3%, respectively; P = .002), be employed (80.3% v 74.7%, respectively; P = .002), and have higher household incomes (P = .02).

Table 1.

Demographics and Cancer-Related Characteristics of Survivors of Childhood Cancer and Siblings

| Characteristic | Survivors (n = 698) |

Siblings (n = 210) |

P† | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Weighted %* | No. | Weighted %* | ||

| Age at survey, years | .06 | ||||

| 22-29 | 214 | 11.3 | 61 | 13.5 | |

| 30-39 | 228 | 42.3 | 68 | 33.6 | |

| 40-62 | 256 | 46.4 | 81 | 52.9 | |

| Sex | .11 | ||||

| Male | 314 | 45.5 | 82 | 38.9 | |

| Female | 384 | 54.5 | 128 | 61.1 | |

| Race/ethnicity | .96 | ||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 646 | 93.5 | 185 | 93.5 | |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 14 | 1.7 | 4 | 1.9 | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 24 | 3.0 | 6 | 2.4 | |

| Other | 12 | 1.8 | 5 | 2.2 | |

| Education | .40 | ||||

| Less than high school through high school graduate | 98 | 14.1 | 19 | 11.7 | |

| Some postgraduate college | 179 | 26.8 | 51 | 23.3 | |

| Completed college | 352 | 59.1 | 122 | 65.0 | |

| Marital status | .002 | ||||

| Married, living as married | 393 | 61.3 | 141 | 73.6 | |

| Single, never married | 240 | 28.5 | 49 | 16.1 | |

| Divorced or separated | 59 | 10.2 | 19 | 10.3 | |

| Employment status | .002 | ||||

| Employed (full time or part time) | 510 | 74.7 | 163 | 80.3 | |

| Unemployed and looking for work | 44 | 6.1 | 8 | 3.0 | |

| Unable to work due to illness or disability | 66 | 9.3 | 4 | 2.2 | |

| Other | 69 | 9.9 | 32 | 14.5 | |

| Household income | .02 | ||||

| < $20,000 | 91 | 12.0 | 12 | 5.2 | |

| $20,000-$39,999 | 106 | 14.9 | 24 | 10.7 | |

| $40,000-$59,999 | 104 | 15.8 | 35 | 16.9 | |

| $60,000-$79,999 | 95 | 14.8 | 32 | 16.1 | |

| > $80,000 | 240 | 38.3 | 90 | 48.7 | |

| Don't know | 36 | 4.2 | 8 | 2.4 | |

| Cancer diagnosis | |||||

| Leukemia | 255 | 35.0 | |||

| CNS | 104 | 14.9 | |||

| Hodgkin lymphoma | 71 | 12.9 | |||

| Neuroblastoma | 67 | 6.1 | |||

| Wilms (kidney) tumor | 66 | 8.1 | |||

| Soft tissue sarcoma | 51 | 8.3 | |||

| Bone | 45 | 8.1 | |||

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | 39 | 6.7 | |||

| Age at diagnosis, years | |||||

| 0-5 | 404 | 46.4 | |||

| 6-10 | 104 | 19.1 | |||

| 11-15 | 109 | 19.8 | |||

| 16-20 | 81 | 14.7 | |||

| Time since diagnosis, years | |||||

| Mean | 30.3 | ||||

| Standard deviation | 4.6 | ||||

| Recurrence of primary malignancy | 611 | 88.1 | |||

| No | 87 | 11.9 | |||

| Yes | |||||

| Subsequent cancer | 668 | 94.9 | |||

| No | 30 | 5.1 | |||

| Yes | |||||

| Prevalence of chronic health condition | < .001 | ||||

| None | 111 | 15.1 | 68 | 32.3 | |

| Mild to moderate | 319 | 45.1 | 114 | 52.0 | |

| Severe to life threatening | 268 | 39.8 | 28 | 15.7 | |

NOTE. The total numbers in the table might not add up to 698 for survivors or 210 for siblings because of missing data.

Percentages are weighted to reflect the population age distribution of the full Childhood Cancer Survivor Study cohort.

P value comparing survivors and siblings.

Insurance Characteristics and Perceptions of the ACA

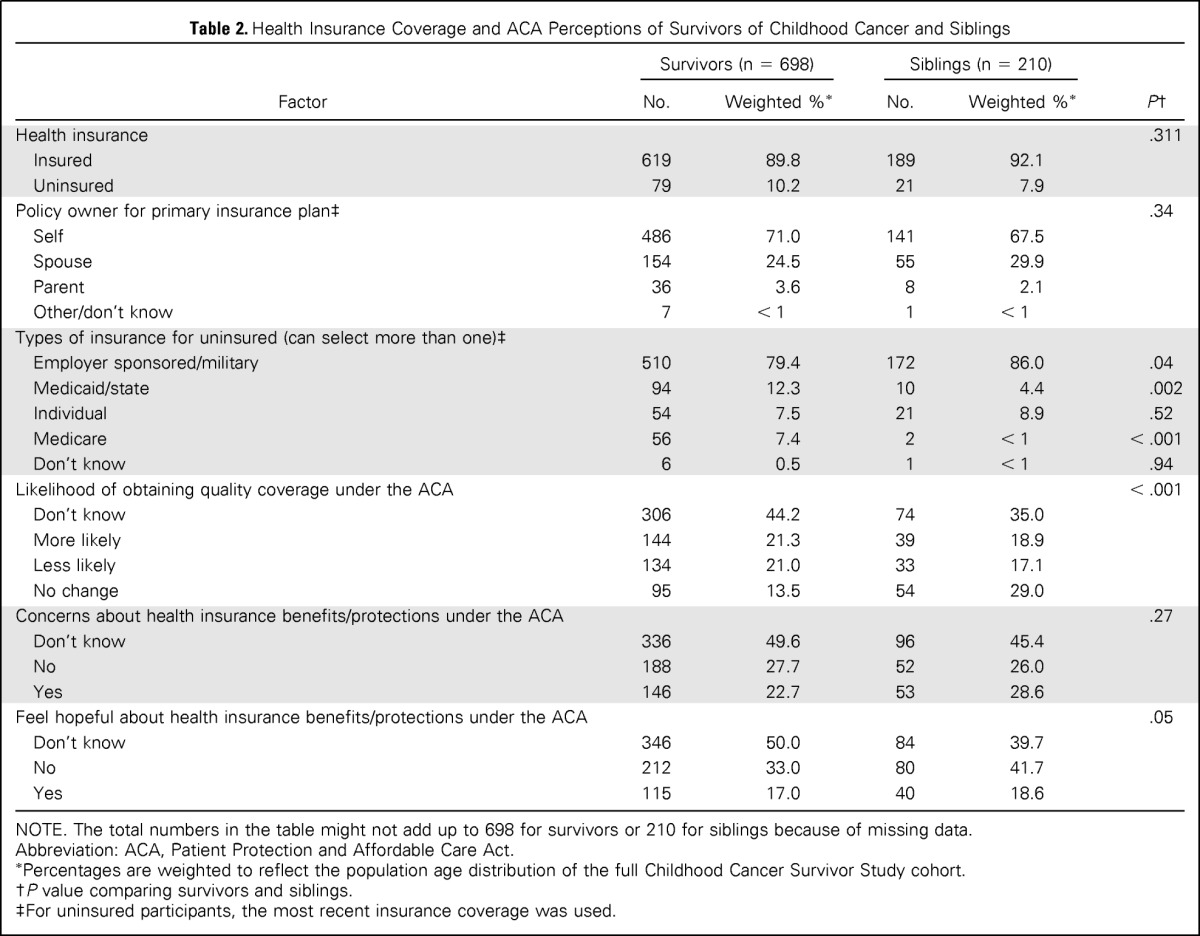

Overall, 89.8% of survivors and 92.1% of siblings were currently insured (P = .31, Table 2). Survivors, compared with siblings, were significantly less likely to have employer-sponsored coverage (79.4% v 86.0%, respectively; P = .04) and more likely to be covered by Medicaid/state insurance (12.3% v 4.4%, respectively; P = .002). Only 21.3% of survivors and 18.9% of siblings reported that the ACA would make it more likely that they would get quality coverage; notably, 44.2% of survivors and 35.0% of siblings responded that they “don't know.” In addition, approximately half of survivors (49.6%) and siblings (45.4%) responded “don't know” regarding concerns about the ACA benefits and protections. Only 17.0% of survivors and 18.6% of siblings felt hopeful about the benefits and protections offered by the ACA.

Table 2.

Health Insurance Coverage and ACA Perceptions of Survivors of Childhood Cancer and Siblings

| Factor | Survivors (n = 698) |

Siblings (n = 210) |

P† | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Weighted %* | No. | Weighted %* | ||

| Health insurance | .311 | ||||

| Insured | 619 | 89.8 | 189 | 92.1 | |

| Uninsured | 79 | 10.2 | 21 | 7.9 | |

| Policy owner for primary insurance plan‡ | .34 | ||||

| Self | 486 | 71.0 | 141 | 67.5 | |

| Spouse | 154 | 24.5 | 55 | 29.9 | |

| Parent | 36 | 3.6 | 8 | 2.1 | |

| Other/don't know | 7 | < 1 | 1 | < 1 | |

| Types of insurance for uninsured (can select more than one)‡ | |||||

| Employer sponsored/military | 510 | 79.4 | 172 | 86.0 | .04 |

| Medicaid/state | 94 | 12.3 | 10 | 4.4 | .002 |

| Individual | 54 | 7.5 | 21 | 8.9 | .52 |

| Medicare | 56 | 7.4 | 2 | < 1 | < .001 |

| Don't know | 6 | 0.5 | 1 | < 1 | .94 |

| Likelihood of obtaining quality coverage under the ACA | < .001 | ||||

| Don't know | 306 | 44.2 | 74 | 35.0 | |

| More likely | 144 | 21.3 | 39 | 18.9 | |

| Less likely | 134 | 21.0 | 33 | 17.1 | |

| No change | 95 | 13.5 | 54 | 29.0 | |

| Concerns about health insurance benefits/protections under the ACA | .27 | ||||

| Don't know | 336 | 49.6 | 96 | 45.4 | |

| No | 188 | 27.7 | 52 | 26.0 | |

| Yes | 146 | 22.7 | 53 | 28.6 | |

| Feel hopeful about health insurance benefits/protections under the ACA | .05 | ||||

| Don't know | 346 | 50.0 | 84 | 39.7 | |

| No | 212 | 33.0 | 80 | 41.7 | |

| Yes | 115 | 17.0 | 40 | 18.6 | |

NOTE. The total numbers in the table might not add up to 698 for survivors or 210 for siblings because of missing data.

Abbreviation: ACA, Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act.

Percentages are weighted to reflect the population age distribution of the full Childhood Cancer Survivor Study cohort.

P value comparing survivors and siblings.

For uninsured participants, the most recent insurance coverage was used.

When comparing insured and uninsured survivors, only 9.3% of uninsured survivors, compared with 22.6% of insured survivors, believed that the ACA would make it more likely for someone with their health history to get coverage; 24.6% of uninsured survivors versus 20.7% of insured survivors believed that the ACA would make it less likely for someone with their health history to get coverage, and 56.2% of uninsured survivors versus 42.9% of insured survivors responded “don't know” (overall P = .04; data not shown).

Importance of Health Plan Coverage, Features, and Cost

Coverage.

Acute cancer-specific care and acute non–cancer-specific care were considered “very important” by more than 80% of survivors and siblings (Table 3). Inclusion of primary care was deemed “very important” by 94.6% of survivors compared with 90.4% of siblings (P = .04).

Table 3.

Coverage Priorities: Plan Coverage, Features, and Cost Ranked As “Very Important”

| Factor | Survivors v Siblings |

Survivors by Insurance Status |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survivors |

Siblings |

P‡ | Insured Survivors |

Uninsured Survivors |

P§ | Multivariable Odds Ratios: Insured v Uninsured Survivors (reference)* |

|||||||

| No. | Weighted %† | No. | Weighted %† | No. | Weighted %† | No. | Weighted %† | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | P | |||

| Plan coverage | |||||||||||||

| Primary care | 639 | 94.6 | 182 | 90.4 | .04 | 569 | 94.9 | 70 | 91.8 | .33 | 1.59 | 0.52 to 4.81 | .41 |

| Acute, cancer-specific care | 579 | 86.0 | 156 | 80.9 | .09 | 517 | 86.3 | 62 | 83.3 | .53 | 1.43 | 0.66 to 3.06 | .36 |

| Acute, non–cancer-specific care | 539 | 81.3 | 158 | 80.4 | .80 | 485 | 82.0 | 54 | 74.8 | .17 | 1.80 | 0.94 to 3.46 | .08 |

| Dental care | 454 | 67.5 | 128 | 63.7 | .34 | 395 | 66.2 | 59 | 79.1 | .04 | 0.52 | 0.26 to 1.02 | .06 |

| Vision care | 408 | 60.7 | 102 | 49.3 | .01 | 359 | 60.1 | 49 | 65.3 | .44 | 0.86 | 0.48 to 1.54 | .62 |

| Mental health care | 271 | 40.2 | 73 | 40.5 | .96 | 239 | 39.4 | 32 | 47.7 | .22 | 0.82 | 0.47 to 1.43 | .49 |

| Plan features | |||||||||||||

| No waiting period before coverage begins | 533 | 79.0 | 140 | 69.7 | .01 | 471 | 78.6 | 62 | 82.0 | .55 | 1.00 | 0.48 to 2.06 | .99 |

| Choice of primary care physician | 518 | 78.3 | 136 | 69.4 | .01 | 465 | 78.8 | 53 | 74.2 | .41 | 1.29 | 0.67 to 2.49 | .45 |

| No coverage limits (lifetime or annual) | 484 | 72.3 | 135 | 67.2 | .19 | 430 | 72.1 | 54 | 74.0 | .76 | 0.95 | 0.50 to 1.82 | .88 |

| Ability to self-refer | 376 | 56.7 | 102 | 51.1 | .19 | 333 | 55.8 | 43 | 64.6 | .19 | 0.74 | 0.41 to 1.32 | .30 |

| Plan cost | |||||||||||||

| Affordable premiums | 594 | 88.1 | 169 | 83.7 | .13 | 523 | 87.4 | 71 | 94.2 | .15 | 0.48 | 0.14 to 1.62 | .24 |

| No added expense due to pre-existing conditions | 590 | 87.4 | 141 | 68.9 | < .001 | 523 | 87.2 | 67 | 88.8 | .73 | 1.00 | 0.42 to 2.42 | .99 |

| Low deductible | 496 | 73.4 | 135 | 64.5 | .02 | 438 | 72.6 | 58 | 80.3 | .20 | 0.68 | 0.35 to 1.34 | .26 |

| Low co-pay | 497 | 72.9 | 136 | 66.3 | .09 | 437 | 72.2 | 60 | 79.6 | .22 | 0.69 | 0.34 to 1.36 | .28 |

Models adjusted for current age, sex, marital status, and chronic disease.

Percentages are weighted to reflect the population age distribution of the full Childhood Cancer Survivor Study cohort.

P value calculated for survivors and siblings, comparing those who indicate these features as “very important” with those rating the features as “somewhat important” to “not at all important.”

P value comparing insured survivors with uninsured survivors.

Features.

A majority of survivors and siblings rated no waiting period (79.0% v 69.7%, respectively; P = .01) and choice of primary care physician (78.3% v 69.4%, respectively; P = .01) as “very important,” although with significantly greater endorsement by survivors.

Cost.

Affordable premiums were rated as “very important” by the greatest number of survivors and siblings (88.1% v 83.7%, respectively; P = .13). No added expenses due to pre-existing conditions were supported by most survivors (87.4%) but by fewer siblings (68.9%; P < .001). Low deductible was ranked as “very important” by 73.4% of survivors and 64.5% of siblings (P = .02).

Comparisons between insured and uninsured survivors.

There were no differences between insured survivors and uninsured survivors in importance ratings for plan features and costs. Importance of dental coverage was the only area in which uninsured and insured survivors differed, with 79.1% of uninsured survivors versus 66.2% of insured survivors (P = .04) rating this coverage as “very important.” These results held when we examined health plan coverage, features, and cost in multivariable logistic regression models.

Familiarity With Health Insurance–Related Legislation

Overall, self-reported familiarity with health insurance–related laws was low and did not differ significantly between survivors and siblings (Fig 2A). Only 27.3% of survivors and 26.2% of siblings reported familiarity with the ACA, and in comparison, less than 40% of survivors and siblings reported familiarity with the long-standing ADA. Familiarity was the highest with the FMLA.

Fig 2.

Familiarity of (A) survivors of childhood cancer and their siblings and of (B) insured and uninsured survivors with health insurance–related legislation. Multivariable logistic regressions adjusted for current age, sex, marital status, and chronic disease. Models comparing survivors and siblings were also adjusted for insurance status. ACA, Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act; ADA, Americans with Disabilities Act; COBRA, Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act; FMLA, Family Medical Leave Act; HIPAA, Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act; OR, odds ratio.

Uninsured survivors were significantly less likely than insured survivors to report familiarity with these laws (Fig 2B). Familiarity with the ACA was greater among the insured than the uninsured (29.0% v 12.1%, respectively); insured survivors were 2.86-fold (95% CI, 1.28-fold to 6.36-fold) more likely than uninsured survivors to endorse familiarity with the benefits and protections of the ACA. Insured survivors were also more than twice as likely as uninsured survivors to report familiarity with the FMLA (52.7% v 29.3%, respectively; odds ratio [OR], 2.19; 95% CI, 1.19 to 4.05), COBRA (42.6% v 22.4%, respectively; OR, 2.41; 95% CI, 1.26 to 4.60), and HIPAA (46.2% v 23.7%, respectively; OR, 2.40; 95% CI, 1.26 to 4.56).

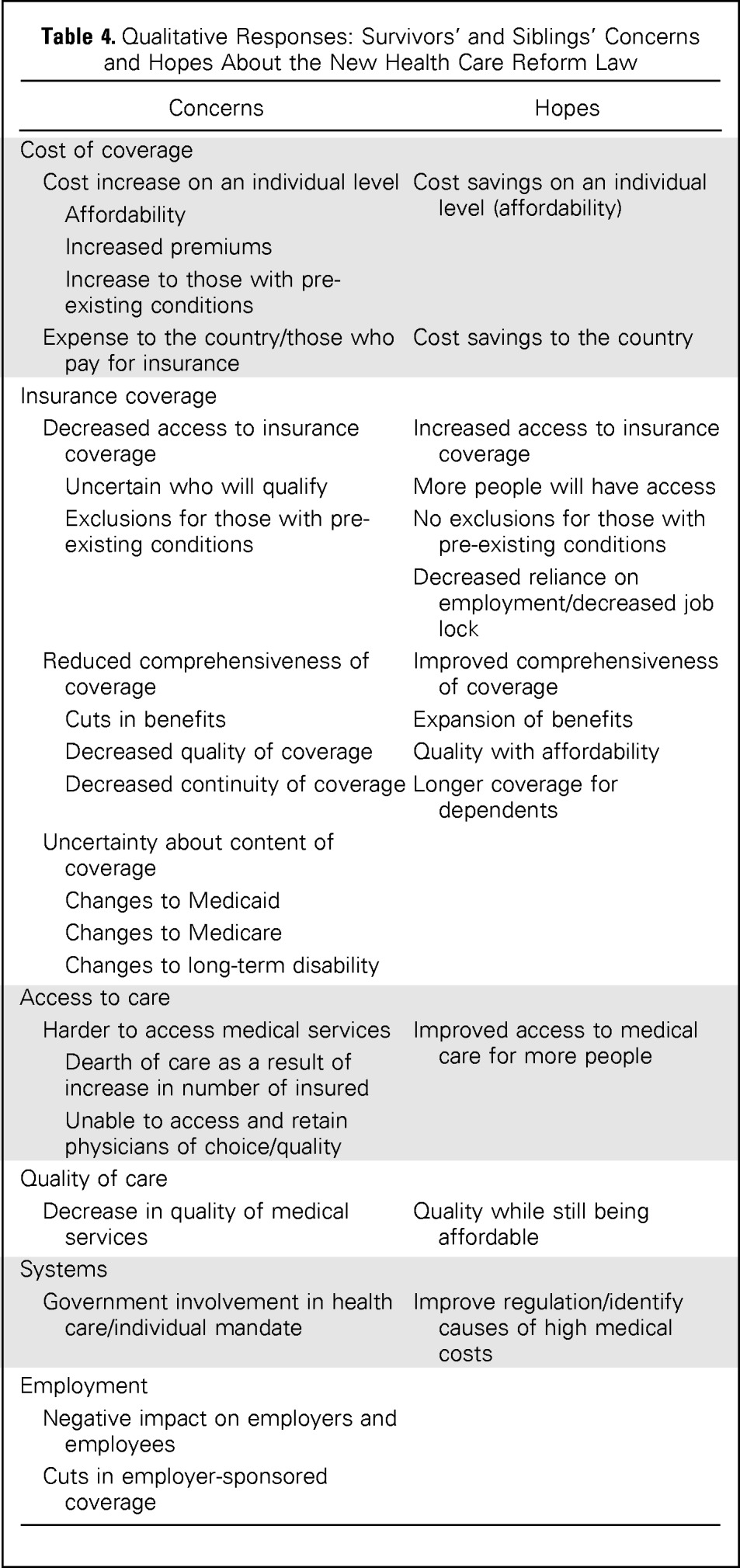

Concerns and Hopes About the ACA

Survivors and siblings wrote in responses to open-ended questions about concerns and hopes about the ACA (20% wrote in concerns and 12% wrote in hopes). The content of these responses did not differ between survivors and siblings. However, issues of particular salience to insured survivors and insured siblings included uncertainty about the content of insurance coverage, continuation of coverage (eg, ability to choose their physician of choice), and costs associated with mandated coverage (Table 4).

Table 4.

Qualitative Responses: Survivors' and Siblings' Concerns and Hopes About the New Health Care Reform Law

| Concerns | Hopes |

|---|---|

| Cost of coverage | |

| Cost increase on an individual level | Cost savings on an individual level (affordability) |

| Affordability | |

| Increased premiums | |

| Increase to those with pre-existing conditions | |

| Expense to the country/those who pay for insurance | Cost savings to the country |

| Insurance coverage | |

| Decreased access to insurance coverage | Increased access to insurance coverage |

| Uncertain who will qualify | More people will have access |

| Exclusions for those with pre-existing conditions | No exclusions for those with pre-existing conditions |

| Decreased reliance on employment/decreased job lock | |

| Reduced comprehensiveness of coverage | Improved comprehensiveness of coverage |

| Cuts in benefits | Expansion of benefits |

| Decreased quality of coverage | Quality with affordability |

| Decreased continuity of coverage | Longer coverage for dependents |

| Uncertainty about content of coverage | |

| Changes to Medicaid | |

| Changes to Medicare | |

| Changes to long-term disability | |

| Access to care | |

| Harder to access medical services | Improved access to medical care for more people |

| Dearth of care as a result of increase in number of insured | |

| Unable to access and retain physicians of choice/quality | |

| Quality of care | |

| Decrease in quality of medical services | Quality while still being affordable |

| Systems | |

| Government involvement in health care/individual mandate | Improve regulation/identify causes of high medical costs |

| Employment | |

| Negative impact on employers and employees | |

| Cuts in employer-sponsored coverage |

Survivors' and siblings' most frequently expressed concern about the ACA was its effect on costs, through perceived high costs of coverage for individuals with pre-existing conditions, increased premiums, and out-of-pocket costs. Survivors and siblings were also concerned about decreased access to coverage, comprehensiveness of coverage, quality of insurance, and restrictions of benefits. Access to care concerns focused on the availability of physicians, increased wait time, and insufficient care for those who were in greatest need of care. Concerns also included anticipated decreases in quality of care as a result of increasing numbers of people with insurance, which was described as “socialized medicine” and “rationed care.” Survivors and siblings expressed concern over the government's control in dictating who would get what type of care. Lastly, there were concerns that the ACA requirement to provide employee coverage would cause employers to go out of business, cut coverage, or cut employees.

However, there was a cautious sense of hopefulness for quality, yet affordable, care, with an acknowledgment that the ACA was not the “perfect solution.” Improved insurance access for more Americans was the most frequently expressed hope for the ACA. In particular, survivors were hopeful that they could receive coverage and thus alleviate “job lock” fears (ie, feeling constrained in job mobility as a result of needed employer-sponsored insurance).

DISCUSSION

In 2010, the US government passed the ACA to expand access to affordable care to all citizens. Because one goal of the ACA was to increase access to needed medical care, including surveillance, it is critical to ascertain cancer survivors' perceptions of this legislation. Thus, 1 year after its enactment in 2011, we conducted the first national examination of childhood cancer cancer survivors' desired coverage features, understanding of the ACA and other insurance-related laws, and hopes and concerns.

Of importance is that features of insurance coverage that survivors consider to be “very important” are indeed addressed by the ACA, such as prohibiting waiting periods and coverage limits. Features such as acute, non–cancer-specific care are understandably prioritized by survivors, given the high incidence of chronic health conditions (73%) for childhood cancer survivors 30 years after diagnosis.20,22 Factors that survivors were differentially more likely than siblings to deem “very important,” such as primary care coverage and choice and protections from additional costs due to pre-existing conditions, are also aligned with the ACA legislation. Furthermore, the ACA requires coverage with no out-of-pocket costs for essential health benefits that have an A or B rating by the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF); however, USPSTF guidelines are not based on survivor-specific preventive guidelines and, as such, may not cover an individual's screening recommendations from the Children's Oncology Group guidelines that are tailored to one's cancer or cancer treatment.43

One year after implementation of the ACA and its multiple provisions that could benefit childhood cancer survivors, survivors endorsed low levels of familiarity with the ACA, mirroring that of the general population at the time.44 Although the current survey occurred during the roll out of key ACA provisions such as expanded coverage for young adults, a time of heightened attention and publicity, only a quarter of childhood cancer survivors and siblings were familiar with the ACA. Indeed, even for the long-established ADA, which protects individuals like survivors from discrimination, only a third of survivors and siblings endorsed familiarity. Survivors' lack of familiarity with these laws was consistent with our recent qualitative findings, in which almost all childhood cancer survivors expressed unfamiliarity with health insurance–related legislation.37 This suggests that survivors may not access, or understand, ACA provisions intended for them now that health insurance exchanges are available. Of great concern is that, among survivors, the uninsured were less likely to be familiar with this legislation, indicating that the most vulnerable could be the least likely to use these protections. This is consistent with a recent Kaiser poll that revealed that the uninsured reported low familiarity and less favorability for the ACA than the population at large.45

Given the low levels of familiarity with the ACA, it is not surprising that survivors' impressions of the ACA were unfavorable and uninformed. It is possible that childhood cancer survivors may be influenced by political and media messages regarding the ACA since its passage. It is critical to underscore that almost half of survivors selected the response “don't know” when asked about their concerns, hopes, and expectations for the ACA. Only one in five survivors and siblings felt that the ACA would make it more likely that they would get quality coverage or felt hopeful about the benefits and protections offered under the ACA. This is lower favorability than was reported in Kaiser polls conducted from 2011 to 2012,46 in which one third of Americans rated the ACA favorably. The Kaiser results indicated that those with higher scores of knowledge about the ACA were more likely to believe that they would be better off because of the ACA. Accordingly, given the lack of familiarity with the ACA, our study revealed a dearth of positive expectations written in by survivors and siblings.

Open-ended responses illustrated survivors' and siblings' shared concerns about the ACA's effect on costs, coverage content, access and quality of care, and employment. Insured participants, in particular, expressed concerns about the cost, access, and continuity of care. Past findings showed that approximately one in three childhood cancer survivors have had difficulties obtaining coverage24; however, the ACA may help mitigate the burden of costs reported by survivors through its requirement that companies undergo a review process before issuing rate increases, expanded Medicaid eligibility, and income-based subsidies among those obtaining coverage through insurance exchanges. In addition, survivors' fears of loss of coverage can be allayed by the ACA provision prohibiting policy cancellations when someone gets sick, as well as the requirement, as of 2014, that companies provide coverage, without increased premiums, to individuals with pre-existing conditions. However, although the ACA could increase the number of survivors covered, complying with the individual mandate could remain financially prohibitive for some who choose to remain uninsured. Past research indicates that uninsured survivors minimize and/or avoid their need for health care37; thus, it is possible that these survivors may choose to forgo care even with expanded coverage options, leaving themselves vulnerable to financial penalties.

Although there are many potential benefits of the ACA for survivors, there are also many uncertainties and concerns of which survivors must be made aware. For example, coverage mandates may make premiums go up, and plans in the exchanges may have high levels of cost sharing to offer more affordable premiums,47,48 which would be difficult for survivors needing a lot of medical services. Plans in exchanges may also include narrow networks that limit where members can get care. With the mandate, people may choose these plans because they have lower premiums, but survivors might not be able to see the specialists and seek care at the hospitals they want.

Improved access and affordability were rated by survivors as “very important” but were also written about as a source of both hope and concern. Hopeful sentiments were less frequent and were expressed cautiously. This expressed tone was consistent with previous qualitative work we conducted, in which low coverage expectations were shared among CCSS participants, which belied fears about health and coverage stability.37 The ACA seeks to improve access and affordability through state-run insurance exchanges, Medicaid expansion (although only half of states currently have opted to expand eligibility), extended age of parental coverage, and no denial because of pre-existing condition or coverage limits. Furthermore, the ACA targets improvements on access to and continuity of care for populations with pre-existing conditions, including cancer survivors, through increased funding for community health centers, support for community-based collaborative care networks and medical homes, creating requirements for culturally and linguistically competent care, and covering clinical trial costs.49

Although drawn from an established national data set of childhood survivors, this analysis has noteworthy limitations. Data relating to health insurance status are self-reported from a cohort of survivors with limited numbers of racial and ethnic minorities treated at tertiary cancer centers. Siblings of childhood survivors may not be representative of the national population; it is reasonable to assume that siblings of survivors have a heightened awareness of the importance of access to quality health care and coverage. Open-ended responses about concerns and hopes regarding the ACA were only completed by some survey respondents. Finally, we conducted the survey before the launch of the health insurance exchanges in the fall of 2013; thus, survivors' and siblings' familiarity with the ACA may be higher since this new provision was enacted.

Although survivors' health care coverage priorities are aligned in many important aspects with the ACA, we found a significant lack of understanding about, and low hopefulness for, the ACA. If assumptions can be drawn based on the low level of familiarity with the long-standing ADA and other insurance protections, this foreshadows insurance underutilization, which underscores the need to educate cancer survivors and facilitate their access to insurance coverage. For survivors to benefit from ACA provisions, it is critical that clinicians, hospitals, community-based organizations, and survivor advocacy groups encourage and facilitate utilization of these benefits. In addition, survivor navigators, who may assist survivors to overcome barriers to quality medical care and facilitate access to survivorship care and services,50 may play a critical role. Furthermore, it is recommended that childhood survivors be surveyed in the future to see if their familiarity with the ACA, concerns and hopes about implementation of the ACA, and coverage priorities have changed. To determine whether the ACA was successful at improving access to quality health insurance coverage and its effects on survivors' perceived quality of coverage and care, childhood survivors' utilization of the ACA and care services should be examined, in particular including an assessment of survivor characteristics, such as age and region, associated with ACA utilization.

Footnotes

Supported by the Livestrong Foundation and National Cancer Institute (Grant No. U24 CA55727, G.T. Armstrong, principal investigator). Support to St Jude Children's Research Hospital also provided by Cancer Center Support (CORE) Grant No. CA21765 (R. Gilbertson, principal investigator) and the American Lebanese-Syrian Associated Charities.

Presented, in part, at a poster session at the 2013 New England Cancer Survivorship Research Conference, Boston, MA, May 1, 2013, and 11th Annual American Psychosocial Oncology Society World Congress of Psycho-Oncology, Tampa, FL, February 13-15, 2014.

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest are found in the article online at www.jco.org. Author contributions are found at the end of this article.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Disclosures provided by the authors are available with this article at www.jco.org.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Elyse R. Park, Karen Donelan, Ann C. Mertens, James D. Reschovsky, Gregory T. Armstrong, Leslie L. Robison, Lisa R. Diller, Christopher J. Recklitis, Karen A. Kuhlthau

Collection and assembly of data: Elyse R. Park, Joel S. Weissman, Gregory T. Armstrong, Leslie L. Robison, Karen A. Kuhlthau

Data analysis and interpretation: Elyse R. Park, Anne C. Kirchhoff, Giselle K. Perez, Wendy Leisenring, Karen Donelan, Gregory T. Armstrong, Leslie L. Robison, Mariel Franklin, Kelly A. Hyland, Karen A. Kuhlthau

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Childhood Cancer Survivor Study Participants' Perceptions and Understanding of the Affordable Care Act

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or jco.ascopubs.org/site/ifc.

Elyse R. Park

No relationship to disclose

Anne C. Kirchhoff

Stock or Other Ownership: Medtronic (I)

Giselle K. Perez

No relationship to disclose

Wendy Leisenring

Research Funding: Merck

Joel S. Weissman

No relationship to disclose

Karen Donelan

Research Funding: Johnson & Johnson (Inst)

Ann C. Mertens

No relationship to disclose

James D. Reschovsky

No relationship to disclose

Gregory T. Armstrong

No relationship to disclose

Leslie L. Robison

No relationship to disclose

Mariel Franklin

No relationship to disclose

Kelly A. Hyland

No relationship to disclose

Lisa R. Diller

Stock or Other Ownership: Novartis (I), Celgene (I), Amgen (I), Gilead Sciences (I)

Christopher J. Recklitis

No relationship to disclose

Karen A. Kuhlthau

Stock or Other Ownership: Alnylam (I), Eli Lilly (I), Laboratory Corporation of America (I), Merck (I), Novo Nordisk (I), Pfizer (I), Johnson & Johnson

REFERENCES

- 1.National Cancer Institute. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program Research Data (1973-2011), National Cancer Institute, Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences, Surveillance Research Program, Surveillance Systems Branch, released April 2014, based on the November 2013 submission. www.seer.cancer.gov.

- 2.Robison LL, Hudson MM. Survivors of childhood and adolescent cancer: Life-long risks and responsibilities. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14:61–70. doi: 10.1038/nrc3634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mertens AC, Liu Q, Neglia JP, et al. Cause-specific late mortality among 5-year survivors of childhood cancer: The Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:1368–1379. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Friedman DL, Whitton J, Leisenring W, et al. Subsequent neoplasms in 5-year survivors of childhood cancer: The Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102:1083–1095. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reulen RC, Frobisher C, Winter DL, et al. Long-term risks of subsequent primary neoplasms among survivors of childhood cancer. JAMA. 2011;305:2311–2319. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Olsen JH, Möller T, Anderson H, et al. Lifelong cancer incidence in 47,697 patients treated for childhood cancer in the Nordic countries. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:806–813. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mulrooney DA, Yeazel MW, Kawashima T, et al. Cardiac outcomes in a cohort of adult survivors of childhood and adolescent cancer: Retrospective analysis of the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study cohort. BMJ. 2009;339:b4606. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b4606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lipshultz SE, Adams MJ, Colan SD, et al. Long-term cardiovascular toxicity in children, adolescents, and young adults who receive cancer therapy: Pathophysiology, course, monitoring, management, prevention, and research directions—A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013;128:1927–1995. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182a88099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van der Pal HJ, van Dalen EC, van Delden E, et al. High risk of symptomatic cardiac events in childhood cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1429–1437. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.4730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Armstrong GT, Oeffinger KC, Chen Y, et al. Modifiable risk factors and major cardiac events among adult survivors of childhood cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3673–3680. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.3205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Green DM, Kawashima T, Stovall M, et al. Fertility of male survivors of childhood cancer: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:332–339. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.9037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kadan-Lottick NS, Zeltzer LK, Liu Q, et al. Neurocognitive functioning in adult survivors of childhood non-central nervous system cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102:881–893. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krull KR, Brinkman TM, Li C, et al. Neurocognitive outcomes decades after treatment for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A report from the St. Jude lifetime cohort study. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:4407–4415. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.48.2315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ness KK, Krull KR, Jones KE, et al. Physiologic frailty as a sign of accelerated aging among adult survivors of childhood cancer: A report from the St. Jude lifetime cohort study. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:4496–4503. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.52.2268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ness KK, Mertens AC, Hudson MM, et al. Limitations on physical performance and daily activities among long-term survivors of childhood cancer. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:639–647. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-9-200511010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Langeveld NE, Grootenhuis MA, Voûte PA, et al. Quality of life, self-esteem and worries in young adult survivors of childhood cancer. Psychooncology. 2004;13:867–881. doi: 10.1002/pon.800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zeltzer LK, Recklitis C, Buchbinder D, et al. Psychological status in childhood cancer survivors: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2396–2404. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ness KK, Gurney JG, Zeltzer LK, et al. The impact of limitations in physical, executive, and emotional function on health-related quality of life among adult survivors of childhood cancer: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89:128–136. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.08.123. (abstr) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brinkman TM, Zhu L, Zeltzer LK, et al. Longitudinal patterns of psychological distress in adult survivors of childhood cancer. Br J Cancer. 2013;109:1373–1381. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oeffinger KC, Mertens AC, Sklar CA, et al. Chronic health conditions in adult survivors of childhood cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1572–1582. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa060185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hijiya N, Hudson MM, Lensing S, et al. Cumulative incidence of secondary neoplasms as a first event after childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. JAMA. 2007;297:1207–1215. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.11.1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hudson MM, Ness KK, Gurney JG, et al. Clinical ascertainment of health outcomes among adults treated for childhood cancer. JAMA. 2013;309:2371–2381. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.6296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Armstrong GT, Kawashima T, Leisenring W, et al. Aging and risk of severe, disabling, life-threatening, and fatal events in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1218–1227. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.51.1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Park ER, Li FP, Liu Y, et al. Health insurance coverage in survivors of childhood cancer: The Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:9187–9197. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.7418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pang JW, Friedman DL, Whitton JA, et al. Employment status among adult survivors in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;50:104–110. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Janson C, Leisenring W, Cox C, et al. Predictors of marriage and divorce in adult survivors of childhood cancers: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:2626–2635. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kirchhoff AC, Leisenring W, Krull KR, et al. Unemployment among adult survivors of childhood cancer: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Med Care. 2010;48:1015–1025. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181eaf880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Public Law 111-148, Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-111publ148/pdf/PLAW-111publ148.pdf.

- 29.Collins SR, Rasmussen PW, Doty MM. Gaining Ground: Americans' health insurance coverage and access to care after the Affordable Care Act's first open enrollment period. http://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2014/jul/Health-Coverage-Access-ACA. [PubMed]

- 30.Strunk BC, Reschovsky JD. Trends in U.S. health insurance coverage, 2001-2003. Track Rep. 2004;9:1–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Claxton G, Rae M, Panchal N, et al. Health benefits in 2013: Moderate premium increases in employer-sponsored plans. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32:1667–1676. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.The Kaiser Family Foundation and Health Research and Educational Trust. Employer health benefits 2013 annual survey, The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, No. 8465, 2013. http://kff.org/private-insurance/report/2013-employer-health-benefits/ [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mueller EL, Park ER, Davis MM. What the Affordable Care Act means for survivors of pediatric cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:615–617. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.52.6467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Robison LL, Armstrong GT, Boice JD, et al. The Childhood Cancer Survivor Study: A national cancer Institute–supported resource for outcome and intervention research. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2308–2318. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.3339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Robison LL, Mertens AC, Boice JD, et al. Study design and cohort characteristics of the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study: A multi-institutional collaborative project. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2002;38:229–239. doi: 10.1002/mpo.1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leisenring WM, Mertens AC, Armstrong GT, et al. Pediatric cancer survivorship research: Experience of the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2319–2327. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.1813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Park ER, Kirchhoff AC, Zallen JP, et al. Childhood Cancer Survivor Study participants' perceptions and knowledge of health insurance coverage: Implications for the Affordable Care Act. J Cancer Surviv. 2012;6:251–259. doi: 10.1007/s11764-012-0225-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/National Center for Health Statistics. National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis.htm. [PubMed]

- 39.Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative. National Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs, 2012. http://www.childhealthdata.org/learn/NS-CSHCN.

- 40.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, US Department of Health and Human Services. Medical expenditure panel survey (MEPS), 2009. http://meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/

- 41.Center for Studying Health System Change. Community tracking study (CTS) and health tracking surveys. http://www.hschange.org/index.cgi?data=12.

- 42.The Commonwealth Fund. Kaiser/Commonwealth 1997 National Survey of Health Insurance, 1997. http://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/surveys/1996/kaiser-commonwealth-1997-national-survey-of-health-insurance.

- 43.Landier W, Bhatia S, Eshelman DA, et al. Development of risk-based guidelines for pediatric cancer survivors: The Children's Oncology Group long-term follow-up guidelines from the Children's Oncology Group Late Effects Committee and Nursing Discipline. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:4979–4990. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Kaiser Public Opinion Poll: Pop quiz: Assessing Americans' familiarity with the new health care law, No. 8148, 2011. http://kff.org/health-reform/poll-finding/pop-quiz-assessing-americans-familiarity-with-the/

- 45.The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Kaiser Health Tracking Poll: February 2014, No. 8555-T, 2014. http://kaiserfamilyfoundation.files.wordpress.com/2014/02/8555-t.pdf.

- 46.The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Kaiser Health Tracking Poll: Public Opinion on Health Care Issues, No. 8259-F, 2011. http://kaiserfamilyfoundation.files.wordpress.com/2013/01/8156-f.pdf.

- 47.Galbraith AA, Sinaiko AD, Soumerai SB, et al. Some families who purchased health coverage through the Massachusetts connector wound up with high financial burdens. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32:974–983. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kaiser Family Foundation. Patient cost-sharing under the Affordable Care Act. http://www.kff.org/healthreform/upload/8303.pdf.

- 49.Moy B, Polite BN, Halpern MT, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology policy statement: Opportunities in the patient protection and affordable care act to reduce cancer care disparities. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3816–3824. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.8903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pratt-Chapman M, Simon MA, Patterson AK, et al. Survivorship navigation outcome measures. Cancer. 2011;117(suppl):3573–3582. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]