Abstract

Background

The growing demand for cancer genetic services underscores the need to consider approaches that enhance access and efficiency of genetic counseling. Telephone delivery of cancer genetic services may improve access to these services for individuals experiencing geographic (rural areas) and structural (travel time, transportation, childcare) barriers to access.

Methods

This cluster-randomized clinical trial used population-based sampling of women at risk for BRCA1/2 mutations to compare telephone and in-person counseling for: 1) equivalency of testing uptake and 2) noninferiority of changes in psychosocial measures. Women 25 to 74 years of age with personal or family histories of breast or ovarian cancer and who were able to travel to one of 14 outreach clinics were invited to participate.

Randomization was by family. Assessments were conducted at baseline one week after pretest and post-test counseling and at six months. Of the 988 women randomly assigned, 901 completed a follow-up assessment. Cluster bootstrap methods were used to estimate the 95% confidence interval (CI) for the difference between test uptake proportions, using a 10% equivalency margin. Differences in psychosocial outcomes for determining noninferiority were estimated using linear models together with one-sided 97.5% bootstrap CIs.

Results

Uptake of BRCA1/2 testing was lower following telephone (21.8%) than in-person counseling (31.8%, difference = 10.2%, 95% CI = 3.9% to 16.3%; after imputation of missing data: difference = 9.2%, 95% CI = -0.1% to 24.6%). Telephone counseling fulfilled the criteria for noninferiority to in-person counseling for all measures.

Conclusions

BRCA1/2 telephone counseling, although leading to lower testing uptake, appears to be safe and as effective as in-person counseling with regard to minimizing adverse psychological reactions, promoting informed decision making, and delivering patient-centered communication for both rural and urban women.

Deleterious mutations in BRCA1/2 are associated with a substantially elevated risk of developing breast and ovarian cancer at an early age (1–6). Mutations in these genes are also associated with increased risk of second primary cancers in those already diagnosed (7–10). Thus, identifying women who harbor mutations in these genes can enable them to actively participate in decision-making about prevention, early detection, and treatment (11). However, informing high-risk women of their risks and options for dealing with this personal and familial hazard requires adroit handling of the psychosocial ramifications as well as expert knowledge about medical care (12). Often, providers lack knowledge and training about hereditary breast and ovarian cancer (HBOC) or do not appropriately refer patients for genetic services (13–19).

Several national organizations have established guidelines for HBOC risk assessment and counseling (11,20). Although the guidelines include recommendations that trained cancer genetic professionals provide comprehensive cancer risk assessment and genetic counseling for women diagnosed with breast cancer before the age of 50, less than half of these women receive counseling (21). Access to guideline-concordant genetic counseling and testing may be limited by cost and structural barriers like travel time, appointment availability, transportation availability, and need for childcare, especially for geographically remote populations (13,21–28). Because of increasing demand and access issues, there is an urgent need to evaluate alternative genetic service delivery models, such as telehealth, and compare them to the current standard of care, in-person counseling (29–32).

Telephone counseling can potentially increase the reach of and access to clinical genetic services for people who could not otherwise receive comprehensive counseling. Although the vast majority of genetic counselors (98%) have given BRCA1/2 results by telephone, few (23%) have provided pretest counseling by telephone (33). One randomized trial has established the noninferiority of telephone-based genetic counseling relative to in-person genetic counseling, but this study was conducted with women who sought clinical genetic services at academic medical centers in primarily urban areas in the northeastern United States (34). These women had already overcome both structural and geographic barriers to access counseling. Of note, the study also found that telephone counseling was less expensive than in-person counseling.

To our knowledge, our study is the first randomized equivalency/noninferiority trial of telephone-based BRCA1/2 counseling and testing that primarily used a population-based recruitment strategy and remote in-person counseling for rural and urban women (NCT01346761). To better evaluate the equivalency and noninferiority of telephone counseling for women facing barriers to access, we recruited from across the state of Utah and provided in-person counseling largely at community-based outreach clinics. This unique approach enabled us to assess the reach and impact of the intervention in a geographically diverse population. We hypothesized that: 1) telephone counseling would be noninferior to in-person counseling with regard to psychosocial outcomes, informed decision-making, and quality of life and 2) BRCA1/2 testing uptake would be equivalent.

Methods

Design and Participants

From August 2010 to September 2012, we recruited participants to a two-armed, parallel-cluster, randomized equivalency/noninferiority trial comparing in-person to telephone counseling (NCT01346761) (35). The six-month follow-up was completed in June 2013. Breast and ovarian cancer case patients were ascertained by the Utah Population Database (36) and recruited through the Utah Cancer Registry. Also, female at-risk relatives were recruited through proband cancer case patients who tested positive for a BRCA1/2 mutation. Eligible participants were women aged 25 to 74 years living in Utah who had telephone access, had personal/family histories suggestive of HBOC (20), and who were able to travel to in-person counseling at one (nearest) of 14 clinics (eight in rural areas) (Table 1). We excluded participants who had prior genetic counseling and/or BRCA1/2 testing, who did not appear mentally competent to give informed consent as determined by study staff during screening, or who could not speak and read English fluently. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. The University of Utah Institutional Review Board approved the study. We report this trial following the recommended standards of the extended Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) statement for noninferiority and equivalence trials (37) and cluster-randomized trials (38).

Table 1.

In-person genetic counseling sites

| 1. Bear River Health Dept, Brigham City Office—Brigham City |

| 2. Castleview Hospital—Price |

| 3. Cedar City Institute of Women’s Health—Cedar City |

| 4. Delta Community Medical Center—Delta |

| 5. Emery Medical Center—Castle Dale |

| 6. Fillmore Community Medical Center—Fillmore |

| 7. Garfield Memorial Hospital—Panguitch |

| 8. Huntsman Cancer Institute—Salt Lake City |

| 9. Mountain View Hospital—Payson |

| 10. St. George Surgical Center—St. George |

| 11. Timpanogos Regional Hospital—Orem |

| 12. Uintah Basin Medical Center—Roosevelt |

| 13. Utah Cancer Specialists—Salt Lake City |

| 14. Weber–Morgan Health Dept—Ogden |

Procedure

Randomization and Masking.

Following confirmation of eligibility and completion of baseline surveys, participants were randomly assigned to one of the study arms by the project coordinator, using a computer-generated allocation algorithm on the basis of a randomized blocks method using four, six, or eight patients in each block. Unbeknownst to each family, individuals were randomized by family unit. Staff who conducted the baseline assessments were blinded to the identity of participating relatives.

Treatments.

In-person and telephone counseling were delivered by the same five board-certified genetic counselors using a guideline-concordant semistructured protocol that allowed for personalization of counseling and is similar to that used by others (Tables 2 and 3) (39,40). All sessions were audiotaped for treatment fidelity assessments.

Table 2.

Summary of pretest counseling session protocol

| Pretest education | • Review the study protocol and answer any questions about the study. |

| • Assess baseline knowledge about hereditary breast and ovarian cancer, personal and familial cancer risk, BRCA testing, and reason for participating in genetic education and counseling through this study. | |

| • Discuss breast and ovarian cancer epidemiology. | |

| • Discuss inheritance of cancer and cancer risks associated with BRCA mutations. | |

| • Provide risk assessment for BRCA mutations and discuss availability of BRCA testing. | |

| • Discuss benefits of genetic testing, including potential for early detection and prevention, and reduction of uncertainty. | |

| • Discuss limitations of genetic testing, including incomplete penetrance, meaning of indeterminate/inconclusive test results, and etiologic uncertainty. | |

| • Discuss state/federal protections related to genetic discrimination. | |

| • Discuss the implications of potential test results and family history for other family members. | |

| • Provide assurance of confidentiality of test results and related information. | |

| • Discuss options for cancer screening and risk management and their limitations (whether or not genetic testing is pursued). | |

| • Answer questions. | |

| Pretest counseling | • The counseling part of the intervention was individualized and tailored to the participant’s personal/family history of cancer and expressed interests/concerns about cancer and/or genetic testing. |

| • Explore the psychosocial implications of genetic testing, anticipated reactions to a positive and negative test result, and their intentions to communicate results to family members as well as related interpersonal issues. | |

| • Explore participants’ perceptions about BRCA testing and risk reduction options with regard to knowledge, values, preferences, expectations of outcomes, and risk reduction options for breast and ovarian cancer. | |

| • Assess risk perceptions and correct misconceptions. | |

| • Address any barriers to genetic testing or accessing appropriate cancer screening/risk reduction services the patient endorses. | |

| • Assess and discuss additional concerns or issues expressed by the participant. | |

| • For those who are socioeconomically disadvantaged and underinsured or uninsured, assist the patient in obtaining testing through the Myriad financial assistance program. | |

| • Instruct woman to call the counselor if they encounter access barriers (eg, financial) to testing or desired health services (screening and surgery). | |

| • Provide additional assistance in accessing services and make referrals as needed. | |

| • Answer questions. | |

| • Follow-up: For participants who wish to pursue testing, complete testing paperwork and provide the necessary documentation to help ensure insurance reimbursement for testing. For those who did not wish to pursue genetic testing, or were unsure, send a summary letter of the genetic counseling session. If they desire, send their preferred health care provider a copy of this letter. |

Table 3.

Summary of post-test counseling session protocol

| Post-test result disclosure education | • Provide test results and associated risk estimates. |

| • For mutation carriers, review age-specific penetrance of hereditary breast and ovarian cancer. | |

| • Review probability of breast and ovarian cancers in the general population. | |

| • Provide verbal and written information about options for surveillance and recommendations for preventive measures based on BRCA status. | |

| • For those who do not have a primary care provider (or regular source of health care) or have not recently had cancer screening (depending on age and genetic status) provide referral information (appropriate for socioeconomic status and health insurance status) for cancer screening and risk reduction services. | |

| • Explain altered risks in relatives; make recommendations that adult high-risk relatives be informed of the availability of risk information and genetic counseling. | |

| • For mutation carriers, review inheritance pattern of BRCA1/2 mutations and identify at-risk relatives (including future children when appropriate). | |

| • Mail tailored letter to patient (and their health care provider if they desire) that includes personalized recommendations for the patient and their family members based on their test result. | |

| Post-test result disclosure counseling | • Explore participants’ emotions and concerns. |

| • Make referrals to appropriate physicians, mental health providers and other professionals as requested by the patient or as needed. At the conclusion of the session, the genetic counselor will: 1) explain that she/he is available for questions and to help address concerns by telephone for the duration of the study if needed, and 2) send a results/counseling letter that includes recommendations for surveillance/prevention to the participant’s primary provider if they desire. This is standard genetic counseling practice. | |

| • Explore participants’ preferences regarding cancer screening and risk reduction options based on genetic test result. | |

| • Provide test results and risk education in a supportive manner. | |

| • Assess risk perceptions with regard to their test result and correct misconceptions. | |

| • Explore intentions to communicate test results to at-risk and other family members and discuss concerns and issues. | |

| • Answer questions. | |

| • Assess and discuss additional concerns or issues expressed by the participant. | |

| Provisions for follow-up | |

| • Make follow-up/referral arrangements. | |

| • Instruct participants to contact counselor if they encounter barriers to accessing services. | |

| • Send BRCA test results/counseling letter that includes recommendations for surveillance/ prevention to the patients’ preferred primary care provider if they desire. |

Participants randomly assigned to telephone counseling were mailed packets that included a sealed envelope containing an educational brochure about HBOC genetic counseling with visual aids. At the time of their session, participants opened their envelope and counselors used the visual aids to explain breast-ovarian cancer genetics. Women receiving in-person counseling were given these same materials during their session at the community clinic.

For women who elected to have testing, those who had telephone counseling were sent a genetic test kit; those who had in-person counseling had the option of giving a sample immediately at the clinic, or if they preferred, they were given a test kit with the same instructions as those in the telephone-counseling group.

When BRCA test results became available, participants were offered individual post-test counseling with the same genetic counselor who conducted the pretest session. As with the pretest session, participants in both study arms were mailed or given visual aids tailored to the participant’s genetic test result, but including recommendations for both positive and negative test results to avoid revealing the participant’s result.

Data Collection and Measures.

Eligibility data were collected by telephone. Evidence-based procedures were used for collection of baseline and outcome data, including $2 incentives to engage nonresponders to complete follow-up surveys (41). Data collectors, blinded to intervention assignment, collected baseline and outcome data via self-report at baseline (including demographics) one week after pretest and post-test counseling and six months after the last counseling session. The one-week interval was chosen to balance measurement of knowledge and patient-centered communication from the counseling sessions, with effects of counseling on the individual’s psychosocial well-being, while in the case of pretest counseling assessment minimizing the potential contamination from receiving testing results.

Rural/urban residence determination was based on Rural-Urban Commuting Area (RUCA) codes (42).

Genetic testing uptake was established when testing occurred within three months of pretest counseling, and the genetic test results were received by study counselors.

Anxiety was measured at all assessments with the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI)-18 (43). The anxiety subscale was calculated from the six anxiety-related symptoms (Cronbach’s alphas = 0.83–0.86; range of possible scores is 0–24). Higher scores indicate greater anxiety.

Cancer-specific distress was measured at all assessments with the Impact of Event Scale (IES) (αs = 0.90–0.91; range of possible scores is 0–75) (44). This 15-item scale measures participant’s intrusive thoughts about their cancer history. Higher scores indicate more cancer-specific distress.

Decisional conflict regarding BRCA1/2 testing was measured at six months with the 16-item version of the Decisional Conflict Scale (45,46). Higher scores indicate greater decisional conflict (α = 0.72; range of possible scores is 0–100.).

Distress or regret regarding the decision whether or not to undergo BRCA1/2 testing was measured at six months with the five-item Decision Regret Scale (47). Higher scores indicate more decisional regret (α = 0.91; range of possible scores is 0–100).

BRCA1/2 knowledge was measured at baseline and one week after pretest and post-test counseling with an adapted 10-item index (48). Scores were the number correct. The range of possible scores is 0–10.

Mental and physical quality of life were measured at baseline, one week after post-test counseling and at six months with the 12-item SF-12v2™ Health Survey, a measure of functional health from the patient’s perspective. The mental (αs = 0.89–0.90) and physical component summaries (αs = 0.89–0.90) were derived from the eight health domains assessed (49,50). The range of possible scores for both measures is 0–100. Higher scores reflect better quality of life.

Patient-centered communication was assessed one week after pretest counseling with an adapted 13-item measure (51). Higher scores indicate more positive participant perceptions of the counselors’ informativeness (α = 0.83; possible score range = 5–25), interpersonal sensitivity (α = 0.77; possible score range = 3–15), and partnership building (α = 0.72; possible score range: = 5–25). .

Statistical Analysis

Changes from baseline in anxiety and cancer-specific distress at six months were the primary noninferiority outcomes of interest because distress was identified as a potential disadvantage of telephone counseling that could adversely impact quality of life and cognitive processing of genetic risk communication (26,52); other outcomes were considered secondary. Noninferiority margins were based on clinically meaningful changes established in the literature when available (IES and Decisional Conflict: 4 points; Mental and Physical Components Summary: -2.5 points) (44,46,49). For the remaining measures, noninferiority margins were set at no more than 0.5 standard deviation “worse” than the in-person counseling means based on standard deviations from prior studies (Anxiety: 5 points; Decisional Regret: 5 points; Knowledge: 1 point; Informativeness: 1 point; Interpersonal Sensitivity: 0.5 point; Partnership Building: 1.5 points) (53–55). Half a standard deviation reflects meaningful change in health-related quality of life across a range of conditions and individuals (56). The between-group intervention differences in psychosocial outcomes were estimated using linear models together with one-sided 97.5% cluster bootstrap confidence intervals (CIs) calculated in the same manner as the difference in uptake. The one-sided 97.5% CI was used for these noninferiority analyses, because the goal was to test whether telephone counseling was not unacceptably worse than in-person counseling. For the exploratory analysis of rural/urban group differences, psychosocial outcomes were estimated using linear models and differences between the groups were based on 95% bootstrap CIs. A primary outcome was genetic testing uptake equivalency of telephone and in-person counseling. Equivalency, and not noninferiority, was tested, because the goal of genetic counseling is to facilitate informed decision making about testing rather than to increase testing (20). To test for the equivalency of uptake, while accounting for the correlation within families, a cluster bootstrap method was used to estimate the 95% CI for the difference between test uptake proportions (equivalence range = ±10%) (57). A 95% CI was used for the equivalency analysis, because the goal was to test whether the interventions were the same in testing uptake. The difference in uptake proportions was estimated from 1000 bootstrap samples using a logistic regression model. All analyses were run using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) or R 2.15.0 (R Development Core Team, 2012, Vienna, Austria).

For analyses after imputation of missing data, missing psychosocial and informed decision-making scores were substituted with estimates biased toward inferiority. In-person counseling missing data was replaced with the in-person counseling mean. Telephone counseling missing values were replaced with the in-person counseling mean ± the noninferiority margin. Multiple iterative linear regression imputation was used to impute missing values within study testing information using the MI package in R (available at: http://www.jstatsoft.org/v45/i02/) (58). Participants with missing information about testing uptake were those who did not complete the intervention. Cancer status, number of relatives with breast cancer and/or ovarian cancer, education level, household income, health insurance status, and baseline cancer-specific distress were included in the imputation model.

Sample Size

Using NQuery Advisor 7.0 (59), we calculated that an initial sample size s0 = 792 women (396 per group) would provide 80% power based on the hypothesized 25% genetic test uptake rate, 95% confidence, and 10% two-sided equivalence margin. Adjustment for Intra-class correlation was made using the “variance inflation” adjustment for group-randomized studies (60). With a planned mean cluster size of 1.5, a planned retention rate of 85%, and an intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.05, we obtained a planned final sample size s2 = 954 (477 per group). Based on the final randomized sample size of 988, observed genetic testing uptake of 27%, 91% retention, mean cluster size of 1.025, and an ICC of 0.15, our power was 84% to detect test uptake equivalence and greater than 99% to detect changes in general and cancer-specific distress that violated noninferiority.

Results

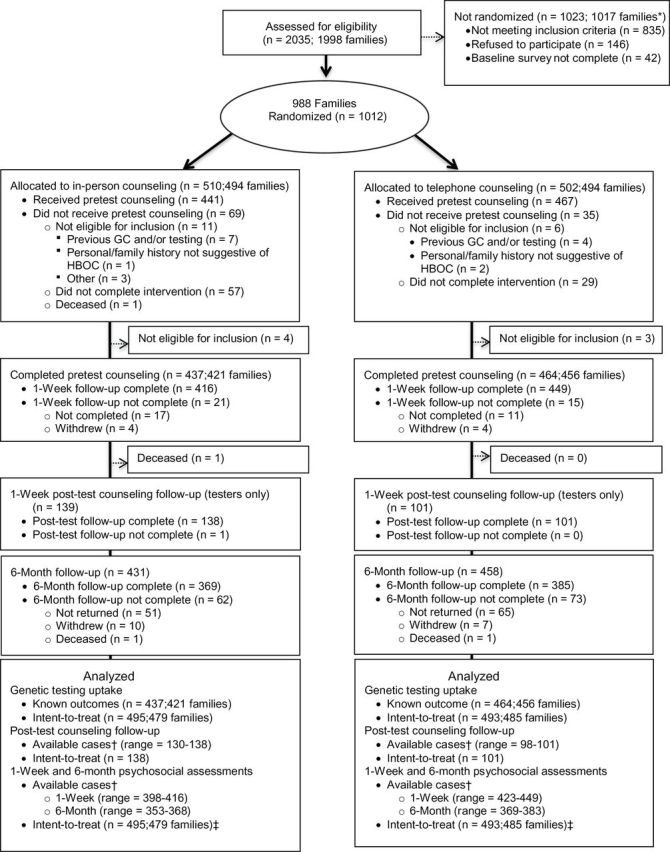

Enrollment, randomization, and retention data are shown in the CONSORT flowchart (Figure 1). Eligibility of 2035 women from 1998 families was assessed. Of 1200 deemed eligible, we enrolled a total of 1012 individuals (84.3%) and randomized them according to family to either the telephone or in-person counseling arm. Of those enrolled, 24 were later deemed ineligible, resulting in 495 women randomized to in-person counseling and 493 women randomized to telephone counseling. 901 completed a follow-up assessment.

Figure 1.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flowchart. * Seven families had at least one member randomized and one member not randomized. † N depends on completion of intervention and completion of measure (see Table 5). ‡ Intent-to-treat refers to data analysis after imputation of unknown testing uptake. GC = genetic counseling. HBOC = hereditary breast and ovarian cancer.

The demographic characteristics of the intervention groups were similar (Table 4). At baseline, the groups did not differ on any measure (Table 5).

Table 4.

Characteristics of women participating in population-based randomized trial comparing telephone to in-person counseling for BRCA1/2 testing

| Characteristic | Overall (n) | In-person (n) | Telephone (n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | |||

| Mean | 56.1 (988) | 55.9 (495) | 56.2 (493) |

| Standard deviation | 8.2 | 8.3 | 8.1 |

| Self-reported race/ethnicity, % | |||

| Non-Hispanic white | 94 (930) | 93 (458) | 96 (472) |

| Hispanic | 3 (32) | 4 (22) | 2 (10) |

| Other | 3 (26) | 3 (15) | 2 (11) |

| Self-reported Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry, % | |||

| Yes | 1 (9) | 1 (3) | 1 (6) |

| No | 99 (979) | 99 (492) | 99 (487) |

| Marital status, % | |||

| Married or living as married | 79 (784) | 79 (389) | 80 (395) |

| Single/widowed/Separated/divorced | 21 (204) | 21 (106) | 20 (98) |

| Educational level, % | |||

| High school or less | 22 (215) | 20 (99) | 24 (116) |

| Some college, Associates degree, or vocational school | 38 (374) | 41 (205) | 34 (169) |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 40 (399) | 39 (191) | 42 (208) |

| Rural/Urban residence, %* | |||

| Urban | 85 (844) | 86 (426) | 85 (418) |

| Rural | 15 (144) | 14 (69) | 15 (75) |

| Household income, yearly, % | |||

| <$29999 | 13 (128) | 12 (59) | 14 (69) |

| $30000-49999 | 19 (190) | 21 (106) | 17 (84) |

| $50000-69999 | 19 (188) | 19 (94) | 19 (94) |

| >$70000 | 45 (441) | 45 (221) | 45 (220) |

| Missing | 4 (41) | 3 (15) | 5 (26) |

| Employment status, % | |||

| Employed (for wages or self-employed) | 62 (613) | 63 (312) | 61 (301) |

| Nonemployed | 38 (375) | 37 (183) | 39 (192) |

| Health care coverage, % | |||

| Yes | 97 (957) | 98 (486) | 96 (471) |

| No | 3 (31) | 2 (9) | 4 (22) |

| Has a personal health care provider, % | |||

| Yes | 89 (876) | 89 (439) | 89 (437) |

| No | 11 (112) | 11 (56) | 11 (56) |

| Personal history of breast and/or ovarian/Fallopian tube/peritoneal cancer, % | |||

| Yes | 97 (963) | 97 (478) | 98 (485) |

| No | 3 (25) | 3 (17) | 2 (8) |

| Personal history of ovarian cancer, % | |||

| Yes | 8 (75) | 7 (36) | 8 (39) |

| No | 92 (913) | 93 (459) | 92 (454) |

| Recruited relative, % | 2.5 (25) | 3.4(17) | 1.6 (8) |

* Rural/urban residence was based on Rural-Urban Computing Area (RUCA) codes at the zip code level. RUCA codes were developed by the University of Washington Rural Health Research Center and the US Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service (ERS), with the support of the federal Health Resource and Service Administration’s Office of Rural Health Policy and the ERS using standard Census Bureau urbanized area and urban cluster definitions in combination with work commuting data to characterize census tracts and later zip codes. The 10 RUCA categories were aggregated into urban (1–3) and rural (4–10) as recommended by the Washington, Wyoming, Alaska, Montana, and Idaho (WWAMI) Rural Health Research Center.

Table 5.

Means and 95% CIs for outcome measures at baseline and each assessment*

| Outcome measures | Baseline | 1 week after pretest counseling | 1 week after post-test counseling, tested women only |

6 months after last counseling session | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Mean (95% CI) | No. | Mean (95% CI) | No. | Mean (95% CI) | No. | Mean (95% CI) | ||

| Telephone genetic counseling | |||||||||

| Anxiety | 493 | 2.8 (2.5 to 3.0) | 449 | 2.3 (2.0 to 2.6) | 101 | 2.2 (1.6 to 2.9) | 383 | 2.7 (2.3 to 3.0) | |

| Distress | 490 | 15.4 (14.1 to 16.7) | 447 | 12.9 (11.6 to 14.2) | 100 | 11 (8.7 to 13.3) | 369 | 13.1 (11.8 to14.5) | |

| Decisional conflict | - | - | - | - | - | - | 383 | 35.9 (35.0 to 36.8) | |

| Decisional regret | - | - | - | - | - | - | 377 | 20.53 (18.7 to 22.3) | |

| Knowledge | 465 | 6.9 (6.8 to 7.1) | 423 | 8 (7.9 to 8.2) | 98 | 8.3 (8.0 to 8.5) | - | - | |

| Quality of life-physical | 491 | 49.6 (48.8 to 50.3) | - | - | 101 | 50.5 (48.8 to 52.3) | 382 | 50.1 (49.2 to 51.1) | |

| Quality of life-mental | 491 | 51.3 (50.5 to 52.2) | - | - | 101 | 52.6 (50.9 to 54.4) | 382 | 50.4 (49.4 to 51.3) | |

| Patient centeredness | |||||||||

| Informativeness | - | - | 447 | 21.7 (21.4 to 21.9) | - | - | - | - | |

| Interpersonal sensitivity | - | - | 449 | 13.3 (13.2 to 13.5) | - | - | - | - | |

| Partnership building | - | - | 437 | 19.9 (19.6 to 20.2) | - | - | - | - | |

| In-person genetic counseling | |||||||||

| Anxiety | 495 | 2.6 (2.4 to 2.9) | 416 | 2.2 (1.9 to 2.4) | 138 | 2 (1.6 to 2.4) | 368 | 2.5 (2.2 to 2.8) | |

| Distress | 491 | 15.5 (14.2 to 16.7) | 411 | 12.5 (11.2 to 13.7) | 134 | 14 (11.6 to 16.4) | 353 | 13.4 (12.1 to 14.7) | |

| Decisional conflict | - | - | - | - | - | - | 366 | 35.4 (34.5 to 36.3) | |

| Decisional regret | - | - | - | - | - | - | 359 | 18.5 (16.7 to 20.3) | |

| Knowledge | 476 | 7 (6.9 to 7.2) | 398 | 8.4 (8.2 to 8.5) | 130 | 8.3 (8.1 to 8.6) | - | - | |

| Quality of life-physical | 493 | 49.6 (48.8 to 50.5) | - | - | 138 | 49.1 (47.5 to 50.6) | 361 | 50.7 (49.7 to 51.7) | |

| Quality of life-mental | 493 | 50.9 (50.1 to 51.7) | - | - | 138 | 52.4 (51.0 to 53.7) | 361 | 50.7 (49.8 to 51.7) | |

| Patient centeredness | |||||||||

| Informativeness | - | - | 416 | 22.0 (21.2 to 22.2) | - | - | - | - | |

| Interpersonal sensitivity | - | - | 416 | 13.5 (13.4 to 13.7) | - | - | - | - | |

| Partnership building | - | - | 414 | 20.2 (20.0 to 20.5) | - | - | - | - | |

* Analyses were conducted on differences from baseline for individuals with known scores at both baseline and assessment. Empty cells are time points when these measures were not collected. CI = confidence interval.

Noninferiority of Psychosocial and Informed Decision-making Outcomes

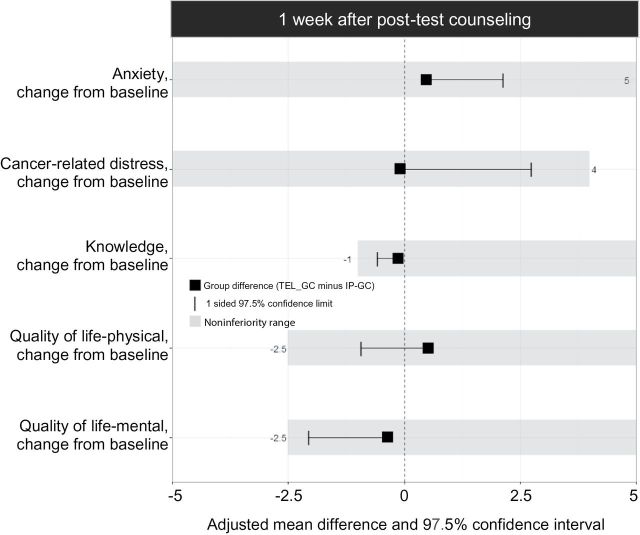

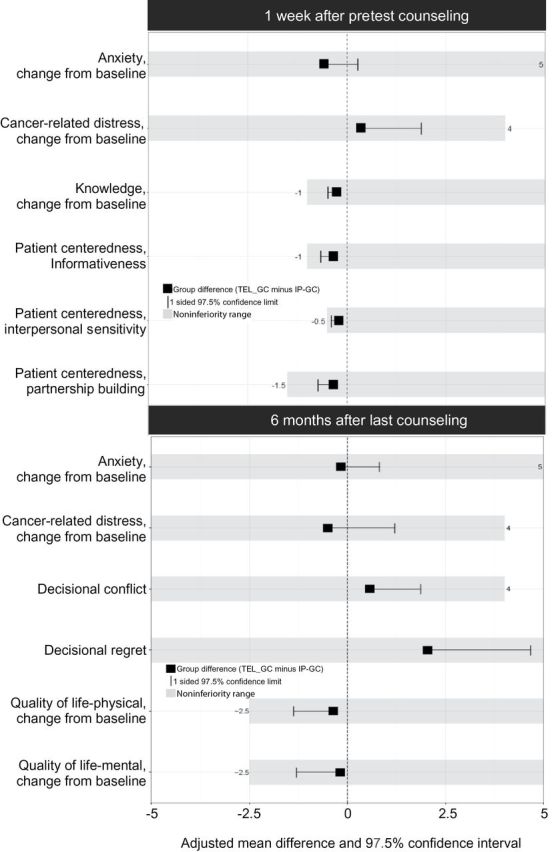

Telephone counseling was noninferior to in-person counseling on all outcomes one week after pretest counseling and six months after last intervention (Figure 2). For those that completed post-test counseling, telephone counseling was noninferior to in-person counseling for all measures one week following disclosure of genetic test results (Figure 3). Imputation-based analysis yielded similar results.

Figure 2.

Effects and noninferiority ranges one week after pretest counseling and six months after the last intervention. The between-group intervention differences were estimated using linear models together with one-sided 97.5% cluster bootstrap confidence intervals. One-sided 97.5% confidence intervals were used, because the goal was to test if telephone counseling was not unacceptably worse than in-person counseling. IP-GC = in-person genetic counseling; TEL-GC = telephone genetic counseling.

Figure 3.

Effects and noninferiority ranges one week after post-test counseling for women who were tested. The between-group intervention differences were estimated using linear models together with one-sided 97.5% cluster bootstrap confidence intervals. One-sided 97.5% confidence intervals were used because the goal was to test if telephone counseling was not unacceptably worse than in-person counseling. IP-GC = in-person genetic counseling; TEL-GC = telephone genetic counseling.

Equivalency of Uptake of Genetic Testing

Telephone counseling was not equivalent to in-person counseling regarding utilization of BRCA1/2 testing. Of those who completed pretest counseling, fewer women were tested after telephone (21.8%) than in-person (31.8%) counseling. Of the 139 women in the in-person genetic counseling group who got tested, 132 (95%) elected to have testing done in the clinic immediately after the counseling session. The other seven (5%) women had BRCA1/2 testing at a later date, ranging from eight days to 49 days after the pretest counseling session. Bootstrap confidence intervals were used to estimate the difference in uptake between the groups (10.2%, 95% CI = 3.9% to 16.3%). Conclusions were similar with imputed data (9.2%, 95% CI = -0.1% to 24.6%).

Rural vs Urban Comparisons

Fifteen percent of the sample resided in rural areas. For all psychosocial and informed decision-making outcomes, when a rural/urban effect was added to the linear model that included the intervention group effect, only minor differences between the rural/urban groups were observed. The confidence intervals for the estimates of the rural/urban group differences all included zero suggesting that rural status did not have an effect on the psychosocial effects of testing for either the telephone or in-person groups (Table 6). On average, testing uptake was higher for rural than urban dwellers in both groups, but the differences were not statistically significant (rural telephone: 31.9%, 95% CI = 22.1% to 43.6%; rural in-person: 38.5%, 95% CI = 27.6% to 50.6%; urban telephone: 20.0%, 95% CI = 16.4% to 24.2%; urban in-person: 30.6%, 95% CI = 26.2% to 35.5%).

Table 6.

Analysis of rural vs urban effects on psychosocial measures*

| Outcome measures | Urban-rural effect averaged across intervention | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 week after pretest counseling | 1 week after post-test counseling (tested women only) | 6 months after last counseling | |

| Effect (95% CI) | Effect (95% CI) | Effect (95% CI) | |

| Anxiety, change from baseline | −0.87 (−1.94 to 0.31) | 0.55 (−1.52 to 2.67) | 0.47 (−0.78 to 1.83) |

| Cancer-related distress, change from baseline | 0.36 (−1.84 to 2.30) | 0.26 (−3.10 to 3.72) | 1.00 (−1.15 to 3.20) |

| Decisional conflict | - | - | −0.43 (−2.36 to 1.47) |

| Decision regret | - | - | 2.15 (−1.31 to 5.72) |

| Knowledge, change from baseline | 0.27 (−0.04 to 0.64) | −0.05 (−0.61 to 0.47) | - |

| Quality of life-physical, change from baseline | - | 0.09 (−1.73 to 2.18) | 1.06 (−0.25 to 2.59) |

| Quality of life-mental, change from baseline | - | 0.30 (−1.80 to 2.42) | −1.37 (−3.06 to 0.12) |

| Patient centeredness | |||

| Informativeness | 0.12 (−.37 to 0.59) | - | - |

| Interpersonal sensitivity | 0.00 (−0.29 to 0.29) | - | - |

| Partnership building | 0.1 (−0.41 to 0.65) | - | - |

* Estimated effect of rural vs urban from linear regression models adjusted for intervention. Models included a random family effect at one week after pretest counseling and six months after last counseling, but not at one week after post-test counseling because cluster sizes were not the same as at randomization. Associated 95% confidence intervals are bootstrap estimates. Analyses varied in the number of participants with complete data at each time point (one week after pretest counseling, the maximum n = 865; one week after post-test counseling, the maximum n = 239; six months after last counseling, the maximum n = 751) (see Table 5 for ns in each analysis). Empty cells are time points when these measures were not collected. CI = confidence interval.

Discussion

Telephone BRCA1/2 genetic counseling fulfilled the criteria for noninferiority to in-person remote genetic counseling with regard to anxiety, cancer-specific psychological distress, quality of life, knowledge, decisional conflict, decisional regret, and patient-centered communication outcomes. Because the goal of genetic counseling is informed decision-making, our findings suggest that HBOC can be added to the list of conditions for which telephone counseling can be safely and effectively delivered. The rural and urban populations did not differ statistically on any outcome measure. Although not statistically significant, the higher uptake of testing in the rural population (35.1%) compared with the urban population (25.2%) suggests that the genetic screening interests of rural populations may be underserved by existing health care systems, perhaps because rural providers are less confident or equipped to provide genetic counseling or because of more barriers faced by rural populations (22,24,26).

Uptake of BRCA1/2 testing was not equivalent following the interventions; telephone counseling led to less testing than in-person counseling. The reason for this difference is unclear. The counseling approach used in our study is standard clinical practice that is consistent with counseling protocols published in the literature and best practices regarding health communications (39,61,62). A similar difference was found with a northeast genetic counseling–seeking sample with much higher uptake of testing overall (87% vs 27% in our study), fewer breast and ovarian cancer diagnoses (65% vs 97% in our study), more individuals of Jewish ethnicity (28% vs 1% in our study), higher educational level (70% had a four-year college degree vs 40% in our study), and household income level (79% reported a household income ≥$50000 vs 64% in our study) (34). The previous study attributed the difference in test uptake rates to the additional travel requirement (to a blood draw site) following telephone counseling. Our findings suggest that it was not travel to a clinic for phlebotomy that led to these patterns, because testing kits were mailed in our study and most were buccal samples. However, travel time associated with dropping the Myriad Laboratories test kit into a Fed-Ex drop box may have somewhat limited access to testing, especially for rural dwellers who may have needed to drive far to the drop-off site. The ease of use of regular US Postal Service might have increased access to testing if this strategy had been employed. Alternatively, the delay between telephone counseling and testing (vs immediate testing after in-person counseling) may have been because of reduced enthusiasm or changed the women’s decisions about testing. Many women in our study expressed concerns about out-of-pocket expenses (30,63). The wait provided the opportunity for women to get additional information about coverage and discuss the decision with social network members, both of which may have influenced their decisions about testing.

A population-based, equivalency/noninferiority clinical trial in which high-risk women are provided with counseling in rural areas is a daunting undertaking, requiring a large sample of eligible women and considerable follow-up for diverse outcomes. Our study was possible because the Utah Population Database (36), and the National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program Utah Cancer Registry enabled us to identify high-risk women expeditiously and recruit across the state. There was some concern that our proactive recruitment approach might result in increased distress in women who undergo genetic counseling with or without testing, and that there may be more adverse psychological sequelae in the telephone counseling group (26). These concerns were not borne out. Both intervention groups showed improvements on measures of anxiety and cancer-specific psychological distress. A similar proactive approach may be used to contact patients identified as meeting testing criteria through oncology practices, state and institutional cancer registries, or tools built into the electronic medical record system to offer them a choice of in-person or telephone counseling. With the proband’s permission, this strategy could also be used to promote cascade testing through at-risk relatives once a mutation is identified.

The relatively low test uptake rate in our study may be related to our proactive recruitment approach, to the fact that the cost of testing was not covered as part of the study, or to differences in demographics of our participants compared with those in other studies (34,64). Furthermore, our study did not focus on women who were members of families with a known BRCA1/2 mutation that may lead to higher uptake rates.

The study’s findings have implications for clinical care and health policy. Telephone delivery has the potential to increase reach of and access to genetic counseling (14,16,23–25,32) as the demand for genetic counseling increases. Although requested and preferred (65) by many patients, telephone counseling is not frequently offered because consensus-approved guidelines suggest that in-person counseling is better than telephone counseling, and there is a lack of evidence supporting telephone counseling as an alternative genetic service delivery model (33,40). While some insurers, such as Aetna, Cigna, and Selecthealth, reimburse consumers for telephone counseling, many do not (66,67). This has been a limitation of telephone counseling. However, our findings and those of a recent study that used a different recruitment and in-person counseling (academic medical center vs community clinics) approach (34) demonstrate similar psychosocial outcomes.

These findings might help justify third-party payment and may motivate provider and institutional practices with regard to utilizing BRCA1/2 telephone counseling. New multigene panel testing for breast cancer hereditary panel testing is rapidly expanding and presents challenges for genetic risk communication, including higher rates of variants of unknown importance that increase the complexity of communicating uncertainties about risk. Research is needed to determine if telephone-based pretest and post-test genetic counseling is not inferior to in-person genetic counseling with regard to psychosocial, behavioral and clinical outcomes and equivalent regarding test uptake for multiplex tests.

Our study had several limitations. First, participants were primarily non-Hispanic white and had a personal history of cancer, which may limit the generalizability of our findings to other populations. However, our findings are consistent with a recent noninferiority trial with a higher percentage of unaffected women who were self-referred and followed for three months post-counseling (34). Further, access to genetic counseling for minorities is improved when telephone delivery is used (68,69). Second, only 27% of women underwent BRCA1/2 testing, thereby restricting our ability to effectively assess for test result subgroup differences. As the cost of testing continues to decline, more women may choose to be tested (63). Third, women in our study were followed up at six months only, which precludes conclusions about the long-term impact of telephone counseling. Finally, our findings may only be relevant to settings in which patients are counseled by board-certified genetic counselors based at an academic cancer center. Further, investigations are needed into the acceptance by clinicians of delivering cancer genetic counseling by telephone and the reach and effectiveness of counseling in diverse settings and with diverse populations.

In conclusion, telephone counseling, although leading to lower testing uptake, appears to be safe and as effective as in-person counseling with regard to minimizing adverse psychological reactions, promoting informed decision making, and providing patient-centered communication. Counseling via telephone can increase the reach of and access to genetic counseling and testing, while potentially reducing both structural barriers and travel-associated costs for both patients and counselors.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health (1R01CA129142 to AYK and U01 CA152958, K05 CA096940, and U01 CA183081 to JSM) and the Huntsman Cancer Foundation. The project was also supported by the Shared Resources (P30 CA042014) at Huntsman Cancer Institute (Biostatistics and Research Design, Genetic Counseling, Research Informatics, and the Utah Population Database [UPDB]); the Utah Cancer Registry, which is funded by Contract No. HHSN261201000026C from the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Program with additional support from the Utah State Department of Health and the University of Utah; the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant 8UL1TR000105 (formerly UL1RR025764).

We would like to thank the Risk Education and Assessment of Cancer Heredity Project participants, who made this research possible, and Roger Edwards, BS, Programmer/Analyst. In addition, we would like to thank the study coordinators, Amy Rogers and Madison Briggs, as well as the staff and administrators at the community clinics.

The authors are solely responsible for the study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of the data, writing the article and decision to submit the article for publication.

References

- 1. Claus EB, Schildkraut JM, Thompson WD, Risch NJ. The genetic attributable risk of breast and ovarian cancer. Cancer. 1996;77(11):2318–2324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Couch FJ, DeShano ML, Blackwood MA, et al. BRCA1 mutations in women attending clinics that evaluate the risk of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 1997;336(20):1409–1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ford D, Easton DF, Stratton M, et al. Genetic heterogeneity and penetrance analysis of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes in breast cancer families. The Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;62(3):676–689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Frank TS, Critchfield GC. Hereditary risk of women’s cancers. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2002;16(5):703–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Martin AM, Blackwood MA, Antin-Ozerkis D, et al. Germline mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 in breast-ovarian families from a breast cancer risk evaluation clinic. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(8):2247–2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Spitzer E, Abbaszadegan MR, Schmidt F, et al. Detection of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in breast cancer families by a comprehensive two-stage screening procedure. Int J Cancer. 2000;85(4):474–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kadouri L, Hubert A, Rotenberg Y, et al. Cancer risks in carriers of the BRCA1/2 Ashkenazi founder mutations. J Med Genet. 2007;44(7):467–471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Finch A, Beiner M, Lubinski J, et al. Salpingo-oophorectomy and the risk of ovarian, fallopian tube, and peritoneal cancers in women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 Mutation. JAMA. 2006;296(2):185–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mavaddat N, Peock S, Frost D, et al. Cancer risks for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: results from prospective analysis of EMBRACE. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105(11):812–822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cancer risks in BRCA2 mutation carriers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91(15):1310–1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Moyer VA. Risk Assessment, Genetic Counseling, and Genetic Testing for BRCA-Related Cancer in Women: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(4):271–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nelson HD, Pappas M, Zakher B, Mitchell JP, Okinaka-Hu L, Fu R. Risk Assessment, Genetic Counseling, and Genetic Testing for BRCA-Related Cancer in Women: A Systematic Review to Update the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(4):255–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Acheson LS, Stange KC, Zyzanski S. Clinical genetics issues encountered by family physicians. Genet Med. 2005;7(7):501–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Carroll JC, Brown JB, Blaine S, Glendon G, Pugh P, Medved W. Genetic susceptibility to cancer. Family physicians’ experience. Can Fam Physician. 2003;49:45–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Doksum T, Bernhardt BA, Holtzman NA. Does knowledge about the genetics of breast cancer differ between nongeneticist physicians who do or do not discuss or order BRCA testing? Genet Med. 2003;5(2):99–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Scheuner MT, Sieverding P, Shekelle PG. Delivery of genomic medicine for common chronic adult diseases: a systematic review. JAMA. 2008;299(11):1320–1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wideroff L, Vadaparampil ST, Greene MH, Taplin S, Olson L, Freedman AN. Hereditary breast/ovarian and colorectal cancer genetics knowledge in a national sample of US physicians. J Med Genet. 2005;42(10):749–755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Trivers KF, Baldwin L-M, Miller JW, et al. Reported referral for genetic counseling or BRCA1/2 testing among United States physicians. Cancer. 2011;117(23):5334–5343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Vogel TJ, Stoops K, Bennett RL, Miller M, Swisher EM. A self-administered family history questionnaire improves identification of women who warrant referral to genetic counseling for hereditary cancer risk. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;125(3):693–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Genetic/Familial High-Risk Assessment: Breast and Ovarian Version 4.2013. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines) 2013. Available at: http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/genetics_screening.pdf. Accessed August 22, 2013.

- 21. Anderson B, McLosky J, Wasilevich E, Lyon-Callo S, Duquette D, Copeland G. Barriers and facilitators for utilization of genetic counseling and risk assessment services in young female breast cancer survivors. J Cancer Epidemiol. 2012;2012:298745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Trivers KF, Baldwin LM, Miller JW, et al. Reported referral for genetic counseling or BRCA1/2 testing among United States physicians. Cancer. 2011;117(23):5334–5343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Brandt R, Ali Z, Sabel A, McHugh T, Gilman P. Cancer genetics evaluation: barriers to and improvements for referral. Genet Test. 2008;12(1):9–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. D’Agincourt-Canning L. Genetic testing for hereditary cancer: challenges to ethical care in rural and remote communities. HEC Forum. 2004;16(4):222–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fineman R, Doyle D. Public health needs assessment for state-based genetic services delivery. In: Khoury MJ, Burke W, Thomson E, eds. Genetics and Public Health in the 21st Century. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mackenzie A, Patrick-Miller L, Bradbury AR. Controversies in communication of genetic risk for hereditary breast cancer. Breast J. 2009;15(Suppl 1):S25-–S32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Vadaparampil ST, Wideroff L, Breen N, Trapido E. The impact of acculturation on awareness of genetic testing for increased cancer risk among Hispanics in the year 2000 National Health Interview Survey. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15(4):618–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wideroff L, Vadaparampil ST, Breen N, Croyle RT, Freedman AN. Awareness of genetic testing for increased cancer risk in the year 2000 National Health Interview Survey. Community Genet. 2003;6(3):147–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cohen SA, Marvin ML, Riley BD, Vig HS, Rousseau JA, Gustafson SL. Identification of Genetic Counseling Service Delivery Models in Practice: A Report from the NSGC Service Delivery Model Task Force. J Genet Couns. 2013;22(4):411–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Brink S. Telehealth: The Ultimate in Convenience Care. U.S. News & World Report. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hilgart JS, Hayward JA, Coles B, Iredale R. Telegenetics: a systematic review of telemedicine in genetics services. Genet Med. 2012;14(9):765–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Madlensky L. Is it time to embrace telephone genetic counseling in the oncology setting? J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(7):611–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bradbury AR, Patrick-Miller L, Fetzer D, et al. Genetic counselor opinions of, and experiences with telephone communication of BRCA1/2 test results. Clin Genet. 2011;79(2):125–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schwartz MD, Valdimarsdottir HB, Peshkin BN, et al. Randomized Noninferiority Trial of Telephone Versus In-Person Genetic Counseling for Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014: In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Risk Education and Assessment for Cancer Heredity. Available at: http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01346761. Accessed October 2, 2014.

- 36. Hurdle JF, Haroldsen SC, Hammer A, et al. Identifying clinical/translational research cohorts: ascertainment via querying an integrated multi-source database. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2013;20(1):164–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Piaggio G, Elbourne DR, Pocock SJ, Evans SJ, Altman DG. Reporting of noninferiority and equivalence randomized trials: extension of the CONSORT 2010 statement. JAMA. 2012;308(24):2594–2604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Campbell MK, Piaggio G, Elbourne DR, Altman DG. Consort 2010 statement: extension to cluster randomised trials. BMJ. 2012;345:e5661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Peshkin BN, Demarco TA, Graves KD, et al. Telephone genetic counseling for high-risk women undergoing BRCA1 and BRCA2 testing: rationale and development of a randomized controlled trial. Genet Test. 2008;12(1):37–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Trepanier A, Ahrens M, McKinnon W, et al. Genetic cancer risk assessment and counseling: recommendations of the national society of genetic counselors. J Genet Couns. 2004;13(2):83–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Dillman D, Smyth J, Christian L. Internet, Mail, and Mixed-Mode Surveys: The Tailored Design Method. 3rd ed Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 42. University of Washington Rural Health Research Center: Rural-urban communting area codes (version 2.0). 2006. Available at: http://depts.washington.edu/uwruca/. Accessed October 2, 2014.

- 43. Derogatis LR. BSI 18 Brief Symptom Inventory 18: Administration, Scoring, and Procedures Manual. Minneapolis, MN: NCS Pearson, Inc.; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Horowitz MJ, Wilner N, Alvarez W. Impact of events scale: A measure of subjective stress. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1979;41(3):209–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. O’Connor AM. Validation of a decisional conflict scale. Med Decis Making. 1995;15(1):25–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. O’Connor AM. User Manual - Decisional Conflict Scale 1993 [updated 2010]. Available at: http://decisionaid.ohri.ca/docs/develop/User_Manuals/UM_Decisional_Conflict.pdf. Accessed October 2, 2014.

- 47. O’Connor AM. User Manual - Decisional Regret Scale 1996 [updated 2003]. Available at: http://decisionaid.ohri.ca/docs/develop/User_Manuals/UM_Regret_Scale.pdf. Accessed October 2, 2014.

- 48. Wang C, Gonzalez R, Milliron KJ, Strecher VJ, Merajver SD. Genetic counseling for BRCA1/2: a randomized controlled trial of two strategies to facilitate the education and counseling process. Am J Med Genet A. 2005;134A(1):66–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ware J, Jr., Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34(3):220–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ware JE., Jr. SF-36 health survey update. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25(24):3130–3139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Street RL., Jr. Physicians’ communication and parents’ evaluations of pediatric consultations. Med Care. 1991;29(11):1146–1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Eysenck MW, Calvo MG. Anxiety and performance - The processing efficiency theory. Cognition & Emotion. 1992;6(6):409–434. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Wakefield CE, Meiser B, Homewood J, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a decision aid for women considering genetic testing for breast and ovarian cancer risk. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;107(2):289–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Wakefield CE, Meiser B, Homewood J, Ward R, O’Donnell S, Kirk J. Randomized trial of a decision aid for individuals considering genetic testing for hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer risk. Cancer. 2008;113(5):956–965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Zabora J, BrintzenhofeSzoc K, Jacobsen P, et al. A new psychosocial screening instrument for use with cancer patients. Psychosomatics. 2001;42(3):241–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Norman GR, Sloan JA, Wyrwich KW. Interpretation of changes in health-related quality of life: the remarkable universality of half a standard deviation. Med Care. 2003;41(5):582–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Efron B, Tibshirani R. An Introduction to the Bootstrap. Boca Raton, FL: Chapman & Hall/CRC; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Su Y, Gelman A, Hill J, Yajima M. Multiple imputation with diagnostics (mi) in R:Opening windows into the black box. J Stat Software. 2011;45(2):1–31. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Elashoff JD. nQuery Adviro Version 7.0 User’s Guide. Cork: Statistical Solutions Ltd.; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Donner A, Klar N. Design and Analysis of Cluster Randomization Trials in Health Research. London, United Kingdom: Arnold; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Prucka SK, McIlvried DE, Korf BR. Cancer risk assessment and the genetic counseling process: using hereditary breast and ovarian cancer as an example. Med Princ Pract. 2008;17(3):173–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Cameron LD, Marteau TM, Brown PM, Klein WM, Sherman KA. Communication strategies for enhancing understanding of the behavioral implications of genetic and biomarker tests for disease risk: the role of coherence. J Behav Med. 2012;35(3):286–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Pollock A. 2 Competitors Sued by Genetics Company for Patent Infringement. The New York Times. July 10, 2013; Business Day: B3. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Kinney AY, Simonsen SE, Baty BJ, et al. Acceptance of genetic testing for hereditary breast ovarian cancer among study enrollees from an African American kindred. Am J Med Genet A. 2006;140(8):813–826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Sie AS, van Zelst-Stams WA, Spruijt L, et al. More breast cancer patients prefer BRCA-mutation testing without prior face-to-face genetic counseling. Fam Cancer. Sep 26 2014;13(2):143–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Genetic Counseling by Phone. Aetna provides telephone genetic counseling. Available at: http://www.aetna.com/individuals-families/member-tools-forms/phone-genetic-counseling.html. Accessed December 3, 2013.

- 67. Informed Medical Decisions II. InformedDNA and Cigna Collaborate in First National Genetic Testing Program to Require Independent Counseling. 2013. Available at: http://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/informeddna-and-cigna-collaborate-in-first-national-genetic-testing-program-to-require-independent-counseling-216575131.html. Accessed December 3, 2013.

- 68. Armstrong K, Micco E, Carney A, Stopfer J, Putt M. Racial differences in the use of BRCA1/2 testing among women with a family history of breast or ovarian cancer. JAMA. 2005;293(14):1729–1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Pal T, Stowe C, Cole A, Lee JH, Zhao X, Vadaparampil S. Evaluation of phone-based genetic counselling in African American women using culturally tailored visual aids. Clin Genet. 2010;78(2):124–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]