Highlights

-

•

Bilateral femoral neck fractures may occur following grand mal epilepsy attack in young patients.

Keywords: Femoral neck fractures, Epilepsies, Myoclonic, Fractures, Spontaneous

Abstract

Introduction

Bilateral femoral neck fractures can occur due to high- or low-energy trauma, in the presence of various predisposing factors, such as osteoporosis, renal osteodystrophy, hypocalcemic seizures, primary or metastatic tumors, electroconvulsive therapy, epileptic seizures, and hormonal disorders.

Presentation of case

This report presents a case of bilateral femoral neck fractures that occurred during an epileptic attack in a 24-year-old male with mental retardation. His complaints had started after a grand mal epileptic attack 10 days earlier. Bilateral displaced femoral neck fractures (Garden type 4) were seen in lateral radiographs of both hips. The patient was operated on urgently, with closed reduction, three stainless steel cannulated screws, and internal fixation applied to both hips. At postoperative week 12, solid joining was achieved and active walking with complete loading was started.

Discussion

Bilateral femoral neck fractures can occur following a grand mal epilepsy attack in young patients. The use of antiepileptic drugs can also lead to the development of pathological fractures by reducing bone mineral density.

Conclusion

Femoral neck fractures should be suspected in patients with epilepsy who present with severe pain in both hips and an inability to walk. Stainless steel implants can be used for treatment. The viability of the femoral head should be evaluated by scintigraphy. Bone mineral density should be monitored in patients who use anti-epileptic drugs, and internal fixation is preferred in the treatment of femoral neck fractures.

1. Introduction

Femoral neck fractures often occur in elderly osteoporotic patients due to low-energy trauma, and rarely in younger people due to high-energy trauma. Although simultaneous bilateral fractures are relatively uncommon, they have been reported in connection with metabolic diseases (renal osteodystrophy, osteoporosis), after electroconvulsive therapy, and due to stress fractures [1–9]. Bilateral femoral neck fracture is extremely rare subsequent to an epileptic attack. However, the muscle contraction that occurs during electroconvulsive therapy and grand mal epileptic seizures can cause fractures. In this case report, bilateral femoral neck fractures that developed during convulsions in a patient with epilepsy with sequelae of meningitis are presented.

2. Presentation of case

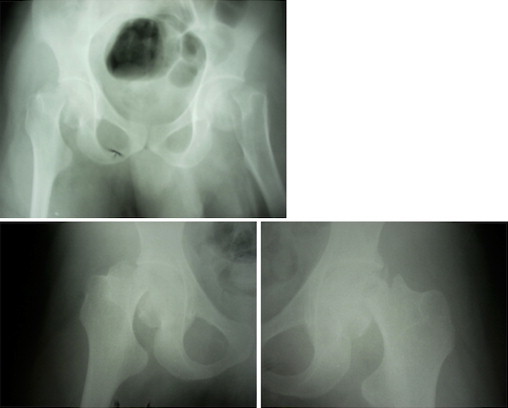

A 24-year-old male was admitted to the emergency orthopedic clinic due to severe pain in both hips and an inability to walk. His complaints had started after a grand mal epileptic attack experienced 10 days earlier. No trauma was established in his history. In the physical examination, it was established that both hips were in an external rotation posture and that movement was painful. Bilateral displaced femoral neck fractures (Garden type 4) were seen (Fig. 1) in both hip lateral radiographs (pelvis anteroposterior view).

Fig. 1.

Preoperative anteroposterior radiographs of both hips.

The patient had suffered from meningitis at the age of 6 months, the sequelae of which had resulted in mental retardation, and epileptic attacks. The patient had been taking hidantin (phenytoin sodium) 100 mg twice per day for 8 years.

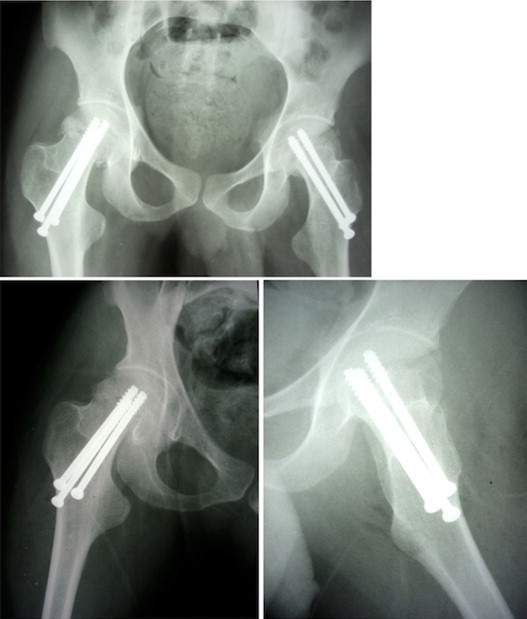

The patient was operated on urgently. A closed reduction and three 6.5 mm-diameter stainless steel cannulated screws, and internal fixation was applied to both hips (Fig. 2). His hip joint capsule was not perforated for decompression.

Fig. 2.

Early postoperative anteroposterior radiographs of both hips.

Osteopenia was found in the measurements of bone mineral density made in the lumbar region (T score −1.9). In-bed mobilization was started on post-operative day 1. Partial loading was not allowed because the patient was mentally retarded. At post-operative week 12, solid joining was achieved and active walking with complete loading was started. There was no evidence of avascular necrosis in the bone scintigraphy.

His Harris hip score was 85 points/right and 87 points/left, in a clinical assessment at post-operative month 15. No evidence of arthritis was found on direct X-rays (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Anteroposterior radiographs of both hips 15 months postoperatively.

3. Discussion

Femoral neck fractures in young patients occur typically as a result of high-energy trauma. In the vast majority of cases, fractures are one-sided. Bilateral femoral neck fractures can occur in the presence of predisposing cause(s) other than very-high-energy trauma. Osteoporosis, renal osteodystrophy, hypocalcemic convulsions, primary or metastatic tumors, electroconvulsive therapy, epileptic attack, and hormonal disorders often cause fractures in these patients, even with low-energy trauma [1–6]. In our case, bilateral femoral neck fractures occurred following a grand mal epilepsy attack.

The use of antiepileptic drugs can also pave the way to the development of pathological fractures by reducing bone mineral density. Chronic use of antiepileptic drugs can decrease serum vitamin D and calcium levels, increase serum parathyroid hormone levels, and increase bone turnover. As a result, bone mineral density can decrease to critical levels, which is associated with a risk of pathological fracture [10]. In our case, long-term use of an antiepileptic drug may have caused the decrease in bone mineral density.

Femoral neck fractures in young patients are treated by early or emergency internal fixation, followed by closed or open reduction. Avascular necrosis is a common complication due to the vascular anatomy of the proximal femur. Although it can develop in any femoral neck fracture, avascular necrosis is particularly frequent (12–40%) in displaced (Garden type 3–4) fractures [11–14]. The risk of avascular necrosis increases if an internal fixation is made in a late manner [15,16]. In our case, surgery was performed on the 10th day due to late presentation. The patient was treated appropriately, although there was some delay in rehabilitation due to adaptation issues caused by the patient's mental retardation and the delay in surgery.

Bone scintigraphy and magnetic resonance are effective methods for the early diagnosis of avascular necrosis of the hip. Although magnetic resonance imaging is easier technically, it is a limited imaging method in the presence of metallic implants. Bone scintigraphy is less influenced by metallic implants [17,18].

4. Conclusion

Bilateral femoral neck fractures can occur following a grand mal epilepsy attack in young patients. For treatment, stainless steel implants can be used. The viability of the femoral head should be evaluated by scintigraphy. Bone mineral density should be monitored in patients who use anti-epileptic drugs, and internal fixation is preferred in the treatment of femoral neck fractures.

Conflicts of interest statement

None.

Funding

None.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Author contribution

None.

Consent

There is no personal/identifying data in the manuscript.

Guarantor

None.

Key learning points

-

•

Bilateral femoral neck fractures can occur following a grand mal epilepsy attack in young patients.

-

•

The use of antiepileptic drugs can also increase the probability of pathological fractures by reducing bone mineral density.

-

•

The viability of the femoral head should be evaluated by scintigraphy. Bone mineral density should be monitored in patients who use anti-epileptic drugs, and internal fixation is preferred in the treatment of femoral neck fractures.

References

- 1.Upadhyay A., Maini L., Batra S., Mishra P., Jain P. Simultaneous bilateral fractures of the femoral neck in children-mechanism of injury. Injury. 2004;35:1073–1075. doi: 10.1016/S0020-1383(03)00190-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fujita S., Morihara T., Arai Y., Chatani K., Takahashi K.A., Fujiwara H. Absence of osteonecrosis of the femoral head following, the high degree of bilateral femoral neck fracture with displacement. J. Orthop. Sci. 2006;11:628–631. doi: 10.1007/s00776-006-1070-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Madho R., Rand J.A. Ten-year follow-up study of missed, simultaneous, bilateral femoral-neck fractures treated by bipolar arthroplasties in a patient with chronic renal failure. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1993;291:185––187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gur S., Yilmaz H., Tüzüner S., Aydin A.T., Süleymanlar G. Fractures due to hypocalcemic convulsion. Int. Orthop. 1999;23:308–309. doi: 10.1007/s002640050377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haddad F.S., Bann S., Hill R.A., Jones D.H.A. Displaced stress fracture of the femoral neck in an active amenorrhoeic adolescent. Brit. J. Sports Med. 1997;31:70–75. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.31.1.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taylor L.J., Grant S.C. Hipocalcemic bilateral fracture of the femoral neck during a convulsion. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. 1985;67B:536–537. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.67B4.4040914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Powell H.D. Simultaneous bilateral fractures of the neck of the femur. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. 1960;42B:236–252. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.42B2.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Devas M.B. Stress fracture of the femoral neck. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. 1965;47B:728––738. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rengman E. Fatigue fractures of the lower extremities: one of bilateral cases of bilateral fatigue fracture of the collum femoris. Acta Orthop. 1959;29:43–48. doi: 10.3109/17453675908988784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pack A. Bone health in people with epilepsy: is it impaired and what are the risk factors? Seizure. 2008;17:181–186. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2007.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Strömqvist B., Hansson L.I., Nilsson L.T., Thorngren K.G. Hook-pin fixation in femoral neck fractures. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1987;218:58–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shih C.H., Wang K.C. Femoral neck fractures. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1991;271:195–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nikolopulos K.E., Papadakis S.A., Kateros K.T., Themistocleous G.S., Vlamis J.A., Papagelopoulos P.J. Patients with Long-term outcome of avascular necrosis, after internal fixation of femoral neck fractures. Injury. 2003;34:525–528. doi: 10.1016/s0020-1383(02)00367-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kawasaki M., Hasegwaw Y., Sakano S., Sugiyama H., Tajima T., Iwasada S. Prediction of osteonecrosis after femoral neck fractures by magnetic resonance imaging. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2001;385:157–164. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200104000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bray T.J., Hoefer E.S., Hooper A., Timmerman L. The displaced femoral neck fracture. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1988;230:127–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee C.H., Huang G.S., Chao K.H., Jean J.L., Wu S.S. Surgical treatment of displaced stress fractures of the femoral neck in military recruits: a report of 42 cases. Arch. Orthop. Trauma. Surg. 2003;123:527–533. doi: 10.1007/s00402-003-0579-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robinson Y., Sandén B. Spine imaging after lumbar disc replacement: pitfalls and current recommendations. Patient Saf. Surg. 2009;3:15. doi: 10.1186/1754-9493-3-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rupp R., Ebraheim N.A., Savolaine E.R., Jackson W.T. Magnetic resonance imaging evaluation of the spine with metal implants. General safety and superior imaging with titanium. Spine (PhilaPa 1976) 1993;18:379––385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]