To the editor:

Several American health care workers and foreign nationals have been treated at community hospitals and/or specialized treatment units in the United States for Ebola virus infection. The better outcomes seen in patients treated in the United States vs West Africa may depend in large part on care guided by diagnostic laboratory testing. At specialized treatment centers including the National Institutes of Health (NIH), dedicated point-of-care laboratories or biosafety level 3 containment clinical laboratories are used. At the NIH Clinical Center, we use “closed” systems for collection, transport, and testing of blood samples from Ebola virus-infected patients. This reduces the risk of infection of laboratory personnel but limits the ability to examine blood or other tissues under the microscope.

Ebola and related viruses can be inactivated by γ irradiation,1 heat,2 lipid solvents,3 or exposure to sodium hypochlorite. We investigated the effect of various methods for virus inactivation on stained peripheral blood smears and found that 3 simple methods for decontaminating Wright-stained peripheral blood smears can be used with no deleterious effects on the quality of the staining.

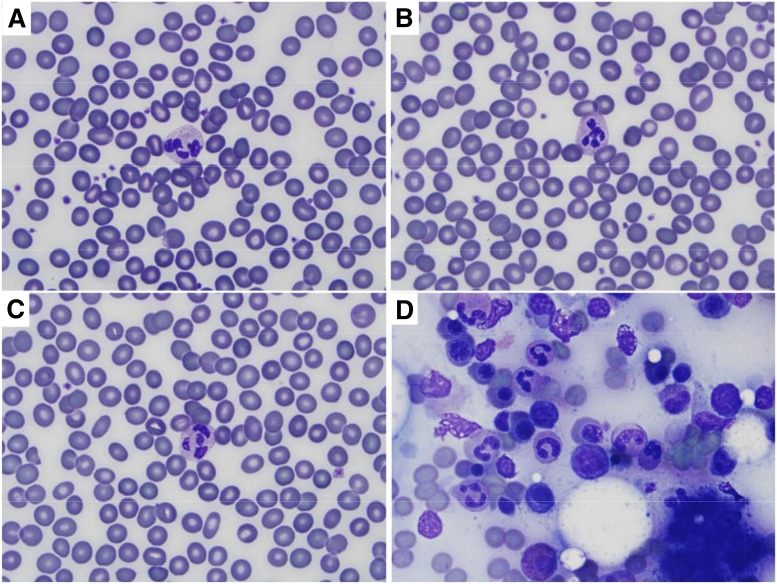

Heat treatment at 60°C for 1 hour has been shown to diminish virus infectivity by 6 log10 in Ebola virus-contaminated serum.2 Air-dried peripheral blood smears were heated in a convection oven for 1 hour at 60°C, 65°C, 68°C, or 95°C before Diff Quik (Medion Grifols Diagnostics AG, Düdingen, Switzerland) staining. Heat inactivation could be done before or after staining with no adverse effect on the quality of the stained smear (Figure 1). Heating at 95°C for 1 hour is one of the empiric recommendations for decontamination of blood samples from patients in Australia with suspected viral hemorrhagic fevers.4

Figure 1.

Wright (Diff Quik) staining of peripheral blood and bone marrow after heat and/or prolonged methanol fixation. Images were captured on an Olympus BX41 microscope using the 100× oil objective, and an Olympus DP72 camera with Olympus CellSens Entry software. (A) Peripheral blood smear heated for 60 minutes at 95°C before staining. (B) Peripheral blood smear fixed in methanol for 30 minutes before staining. (C) Peripheral blood smear heated for 60 minutes at 95°C and then fixed in methanol for 30 minutes before staining. (D) Bone marrow aspirate heated for 60 minutes at 95°C and then fixed in methanol for 30 minutes before staining. Normal erythrocyte morphology and leukocyte details are seen in peripheral blood smears regardless of treatment, and cellular details are preserved in bone marrow aspirate.

Fixation with methanol for 15 or 30 minutes had no effect on the quality of peripheral blood smears prepared by the Diff Quik method (Figure 1). Although there are no data on the effect of methanol on Ebola virus, methanol fixation for 30 minutes (along with heat inactivation) is another part of the recommendations for decontamination of blood samples from patients in Australia with suspected viral hemorrhagic fevers.4

Hypochlorite treatment is widely used for decontamination of fomites, personal protective equipment, and other items that are contaminated with Ebola virus. Immersion of Diff Quik-stained peripheral blood smears in 0.615% sodium hypochlorite (1:10 dilution of household bleach) after application of a coverslip with Cytoseal 60 fixative (Richard-Allan Scientific, Kalamazoo, MI) had no effect on the staining of the blood under the coverslip, whether used for 1, 2, 5, or 10 minutes (not shown).

A typical blood smear is prepared with ∼5 μL of blood. If the Ebola viral load is on the order of 109 per mL (a level observed in blood from patients with acute Ebola virus infection),5 there may be 5 000 000 viral particles on a typical blood smear film. Ebola virus can persist on glass slides for up to 50 days at refrigerator temperature.6 Heat inactivation at 60°C (or even 95°C) for 1 hour may not suffice to inactivate all virus particles in a peripheral blood smear from an acutely infected patient, and the effect on viral infectivity remains to be determined, but chemical and heating methods could be used in combination to provide additional protection for laboratory personnel who may handle contaminated slides until such information is available. The order in which they are done does not affect staining quality with Diff Quik as long as a coverslip is applied before exposure to sodium hypochlorite.

These inexpensive methods for disinfecting and/or heat-inactivating viral pathogens in blood smears are easily adapted for rapid bedside preparation of blood smears or bone marrow aspirates and could be used not only in specialized treatment centers but also in community hospitals faced with caring for Ebola virus-infected patients, an event that we must anticipate will recur in the future. Treatment centers in West Africa without reliable electricity to power ovens for heat inactivation of slides could disinfect slides with methanol fixation and/or bleach treatment of stained slides with coverslips prior to shipment elsewhere for clinical diagnosis or research. Heat inactivation could then be applied to the slides at a central laboratory with more advanced facilities.

Authorship

Acknowledgments: Approval was obtained from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Institutional Review Board for these studies. Informed consent was provided according to the Declaration of Helsinki. The views expressed herein are those of the authors, and do not constitute US government policy.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Intramural Research Program (CL080014).

Contribution: J.N.L. designed and performed the experiments and wrote the letter; and K.R.C. provided samples for staining, performed digital photography, and helped write the letter.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Jay N. Lozier, Hematology Section, Department of Laboratory Medicine, NIH Clinical Center, Room 2C306, MSC 1508, 10 Center Dr, Bethesda, MD 20892-1508; e-mail: lozierjn@cc.nih.gov.

References

- 1.Elliott LH, McCormick JB, Johnson KM. Inactivation of Lassa, Marburg, and Ebola viruses by gamma irradiation. J Clin Microbiol. 1982;16(4):704–708. doi: 10.1128/jcm.16.4.704-708.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mitchell SW, McCormick JB. Physicochemical inactivation of Lassa, Ebola, and Marburg viruses and effect on clinical laboratory analyses. J Clin Microbiol. 1984;20(3):486–489. doi: 10.1128/jcm.20.3.486-489.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klenck H-D, Slenczka W, Feldman H. Marburg and Ebola viruses (Filoviridae). In: Webster RG, Granoff A, editors. Encyclopedia of Virology. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1994. pp. 939–945. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Commonwealth of Australia, Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care, Public Health Laboratory Network. Communicable Diseases Intelligence Technical Report Series: Laboratory Precautions for Samples Collected from Patients with Suspected Viral Haemorrhagic Fevers. Available at: http://www.uphs.upenn.edu/bugdrug/antibiotic_manual/Australiavhf_guide2005.pdf. Accessed January 8, 2015.

- 5.Towner JS, Rollin PE, Bausch DG, et al. Rapid diagnosis of Ebola hemorrhagic fever by reverse transcription-PCR in an outbreak setting and assessment of patient viral load as a predictor of outcome. J Virol. 2004;78(8):4330–4341. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.8.4330-4341.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Piercy TJ, Smither SJ, Steward JA, Eastaugh L, Lever MS. The survival of filoviruses in liquids, on solid substrates and in a dynamic aerosol. J Appl Microbiol. 2010;109(5):1531–1539. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2010.04778.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]