Abstract

Intraosseous access is an alternative route of pharmacotherapy during cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) provides cardiac and respiratory support when conventional therapies fail. This case reports the use of intraosseous thrombolysis and ECMO in a patient with acute massive pulmonary embolism (PE). A 34-year-old female presented to the emergency department with sudden onset severe shortness of breath. Due to difficulty establishing intravenous access, an intraosseous needle was inserted into the left tibia. Echocardiography identified severe right ventricular dilatation with global systolic impairment and failure, indicative of PE. Due to the patient's hemodynamic compromise a recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (Alteplase) bolus was administered through the intraosseous route. After transfer to the intensive care unit, venous-arterial ECMO was initiated as further therapy. The patient recovered and was discharged 36 days after admission. This is the first report of combination intraosseous thrombolysis and ECMO as salvage therapy for massive PE.

Keywords: Cardiac arrest, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, intraosseous, pulmonary embolism, thrombolytic therapy

INTRODUCTION

Pulmonary embolism (PE) remains a major cause of hospital morbidity and mortality.[1] Thrombolysis is indicated in patients with massive PE who are hemodynamically compromised.[2] Thrombolysis is traditionally administered parenterally and there has been limited discussion of alternative routes. We report the use of an intraosseous needle for thrombolysis and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) in a 34-year-old female with massive PE. There are three previous reports of successful intraosseous thrombolysis, with two being in the setting of PE.[3,4,5] There have been no previous reports of intraosseous thrombolysis in combination with ECMO therapy for massive PE.

CASE REPORT

A 34-year-old female patient presented to the emergency department of a tertiary referral hospital with sudden onset severe shortness of breath. On admission, she was hypotensive (90/60 mmHg), tachycardic (140 beats/min), tachypnoeic (50 breaths/min) and had a Glasgow Coma Score (GCS) of 8/15.

Attempts at establishing pre-hospital intravenous access had failed and due to ongoing difficulty, an intraosseous needle was inserted into the left proximal tibia. Due to her acute respiratory distress and poor GCS, rapid sequence intubation was performed and spontaneous intermittent ventilation (pressure controlled) was commenced.

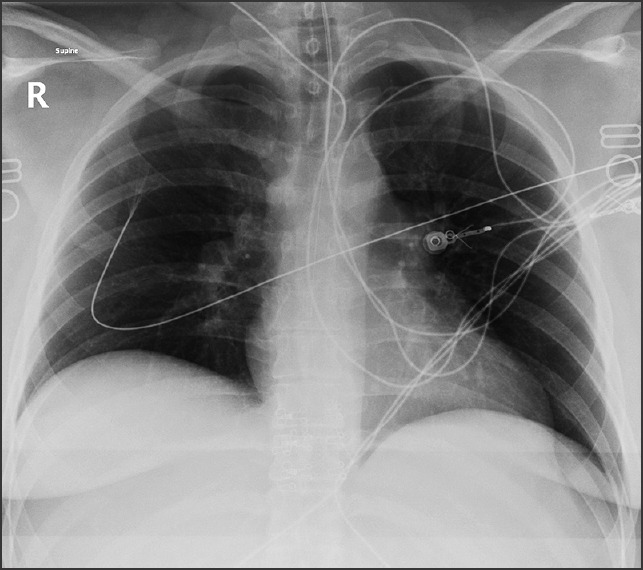

Transthoracic echocardiography identified severe right ventricular dilatation with global systolic impairment and failure. Mobile chest X-ray demonstrated oligemic lung fields [Figure 1]. Based upon clinical presentation and initial radiological findings, diagnosis of PE was made. After intubation, the patient suffered three separate asystolic arrests within a 1 h period. Due to the patient's hemodynamic compromise a recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (Alteplase) bolus of 10 mg was administered over 2 min via the intraosseous needle within the patient's left proximal tibia.

Figure 1.

Mobile chest X-ray displaying oligemic lung fields

After several failed attempts at passing arterial lines, a central venous catheter was inserted into the left internal jugular vein. An Alteplase infusion was subsequently commenced via the left internal jugular central venous catheter at 45 mg/h for 2 h. Ultrasound guidance was used to insert a right femoral central venous catheter and left brachial arterial line. A heparin infusion was initiated at 1500 units/h prior to transfer to the intensive care unit (ICU) for management of ongoing hypoxemia [Table 1].

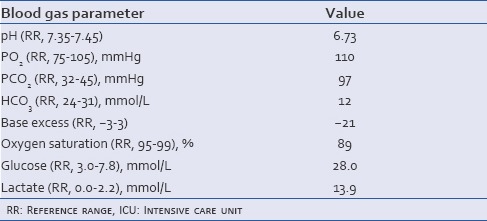

Table 1.

Blood gas results upon admission, prior to transfer to the ICU on 100% FiO2

After consultation with a cardiothoracic surgeon, venous-arterial ECMO was initiated at pump flow 4.2 L/min, pump speed 3151 revs/min and gas flow 4 L/min as further therapy. Within the ICU the patient developed intraperitoneal and groin hemorrhages, disseminated intravascular coagulopathy (DIC), ischemic renal injury and ischemic hepatitis.

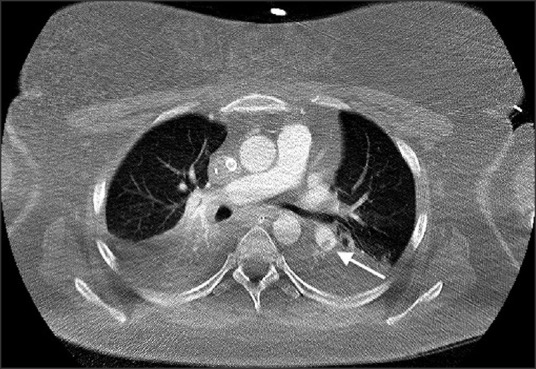

During the first 24 h of admission, computerized tomography with contrast was performed revealing persisting bilateral peripheral pulmonary emboli with bibasal consolidation and pleural effusions [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Computerized tomography pulmonary angiogram (arterial phase, axial slice) demonstrating persisting pulmonary embolus in a branch of the left pulmonary artery (arrow)

After 5 days of ECMO, the patient commenced spontaneous respirations and ECMO was withdrawn. The patient was subsequently successfully weaned from the ventilator. She was extubated and transferred to the ward 19 days after admission to the ICU.

Further investigations for thrombophilia and other coagulopathies were unremarkable. No prior personal or family history of venous thromboemboli were present. The patient consumed tobacco and was on the oral contraceptive pill; the remainder of her background medical history was unremarkable.

Transthoracic echocardiography performed on the ward demonstrated resolution of all right-sided heart changes. The patient was discharged after 36 days in hospital. Out-patient review identified that the patient had fully recovered with no residual abnormalities on clinical and imaging assessments.

DISCUSSION

Use of the intraosseous space for fluid replacement and pharmacotherapy is established in the pediatric literature.[6] Intraosseous access is recommended as an alternate route of pharmacotherapy within adult resuscitation guidelines if intravenous access cannot be achieved in a timely manner.[6] This technique is increasingly used in adults and is useful in emergency scenarios due to its high success rate and ability to be performed concurrently with cardiopulmonary resuscitation.[7]

Previous reports of intraosseous thrombolysis have highlighted this technique as an effective alternative to intravenous pharmacotherapy. There are two descriptions of massive PE management with intraosseous thrombolysis.[3,5] In both cases, tissue plasminogen activator, administered as a weight-adjusted bolus, provided adequate thrombolytic therapy. Intraosseous thrombolysis has also been reported in the setting of acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.[4] Ruiz-Hornillos et al.[4] described coronary artery reperfusion in the setting of shock-refractory ventricular fibrillation after delivery of intraosseous tissue plasminogen activator.

Complications of intraosseous infusions include needle displacement, bone fracture, extravasation of the infusion, compartment syndrome, osteomyelitis and fat embolism.[7] In the case described by Landy et al.,[5] treatment was complicated by tissue necrosis around the site of intraosseous needle. The risk of local hemorrhage and compartment syndrome is increased with the administration of thrombolytic therapy, however, this was not observed in our patient.

There has been limited discussion of the potential role for intraosseous thrombolysis in the management of massive PE. Intraosseous thrombolytic dosage protocols and their pharmacokinetics are aspects that require further consideration in the development of this technique. Consistent with previous reports, we found the standard hospital intravenous thrombolytic protocol to be effective when administered intraosseously.

ECMO is currently indicated for use as a rescue therapy for circulatory and ventilatory support in patients unresponsive to conventional therapeutic techniques;[8] providing cardiorespiratory support through extracorporeal oxygenation of the patient's blood using an artificial lung. The use of ECMO for resuscitation in patients undergoing CPR has been associated with survival rates of up to 38%.[9]

The conventional ventilation or ECMO for severe adult respiratory failure (CESAR) trial assessed the safety and clinical efficacy of ECMO compared to conventional therapy in 180 patients with various causes of respiratory failure.[10] The ECMO group was found to have improved survival without severe disability at 6 months.[10]

Potential ECMO complications include hemorrhage, thromboembolism, hemolysis and brain death.[9] We postulate that in our patient this risk was amplified due to the delivery of thrombolytic agents, resulting in DIC and hemorrhage from the peritoneum and the ECMO outflow cannula; however, due to the patient's dire condition at presentation, the potential adverse events were justifiable risks.

CONCLUSION

We report the case of a 34-year-old female who successfully underwent salvage intraosseous thrombolysis and ECMO for acute massive PE. This unique combination of therapies for PE management has not been previously reported. The case report serves to highlight the importance of appropriate access for the administration of pharmacotherapy in the critically ill patient and reminds clinicians of the potential for ECMO use as a supportive therapy in hemodynamically unstable PE patients.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, Adams RJ, Berry JD, Brown TM, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics — 2011 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123:e18–209. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182009701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jaff MR, McMurtry MS, Archer SL, Cushman M, Goldenberg N, Goldhaber SZ, et al. Management of massive and submassive pulmonary embolism, iliofemoral deep vein thrombosis, and chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123:1788–830. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e318214914f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Valdés M, Araujo P, de Andrés C, Sastre E, Martin T. Intraosseous administration of thrombolysis in out-of-hospital massive pulmonary thromboembolism. Emerg Med J. 2010;27:641–4. doi: 10.1136/emj.2009.086223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ruiz-Hornillos PJ, Martínez-Cámara F, Elizondo M, Jiménez-Fraile JA, Del Mar Alonso-Sánchez M, Galán D, et al. Systemic fibrinolysis through intraosseous vascular access in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;57:572–4. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Landy C, Plancade D, Gagnon N, Schaeffer E, Nadaud J, Favier JC. Complication of intraosseous administration of systemic fibrinolysis for a massive pulmonary embolism with cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2012;83:e149–50. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2012.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deakin CD, Nolan JP, Soar J, Sunde K, Koster RW, Smith GB, et al. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for Resuscitation 2010 Section 4. Adult advanced life support. Resuscitation. 2010;81:1305–52. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2010.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leidel BA, Kirchhoff C, Bogner V, Braunstein V, Biberthaler P, Kanz KG. Comparison of intraosseous versus central venous vascular access in adults under resuscitation in the emergency department with inaccessible peripheral veins. Resuscitation. 2012;83:40–5. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2011.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schuerer DJ, Kolovos NS, Boyd KV, Coopersmith CM. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: Current clinical practice, coding, and reimbursement. Chest. 2008;134:179–84. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-2512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Conrad SA, Rycus PT, Dalton H. Extracorporeal Life Support Registry Report 2004. ASAIO J. 2005;51:4–10. doi: 10.1097/01.mat.0000151922.67540.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peek GJ, Mugford M, Tiruvoipati R, Wilson A, Allen E, Thalanany MM, et al. Efficacy and economic assessment of conventional ventilatory support versus extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe adult respiratory failure (CESAR): A multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;374:1351–63. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61069-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]