Background: NBL1 is a moderate antagonist important for modulating bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling in vivo.

Results: Using x-ray crystallography and mutagenesis, regions important for BMP inhibition within NBL1 were identified.

Conclusion: Modifications to the BMP binding epitope of NBL1 account for differences in its anti-BMP activity.

Significance: This suggests that DAN proteins can be modified to be more effective antagonists for therapeutic purposes.

Keywords: Bone Morphogenetic Protein (BMP), Mutagenesis, Structural Biology, Transforming Growth Factor β(TGF-B), X-ray Crystallography, Differential Screening-aberrative in Neuroblastoma (DAN), Neuroblastoma Suppressor of Tumorigenicity 1 (NBL1), Protein Related to Dan and Cerberus (PRDC), SOST, Extracellular Antagonism

Abstract

Bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) are antagonized through the action of numerous extracellular protein antagonists, including members from the differential screening-selected gene aberrative in neuroblastoma (DAN) family. In vivo, misregulation of the balance between BMP signaling and DAN inhibition can lead to numerous disease states, including cancer, kidney nephropathy, and pulmonary arterial hypertension. Despite this importance, very little information is available describing how DAN family proteins effectively inhibit BMP ligands. Furthermore, our understanding for how differences in individual DAN family members arise, including affinity and specificity, remains underdeveloped. Here, we present the structure of the founding member of the DAN family, neuroblastoma suppressor of tumorigenicity 1 (NBL1). Comparing NBL1 to the structure of protein related to Dan and Cerberus (PRDC), a more potent BMP antagonist within the DAN family, a number of differences were identified. Through a mutagenesis-based approach, we were able to correlate the BMP binding epitope in NBL1 with that in PRDC, where introduction of specific PRDC amino acids in NBL1 (A58F and S67Y) correlated with a gain-of-function inhibition toward BMP2 and BMP7, but not GDF5. Although NBL1S67Y was able to antagonize BMP7 as effectively as PRDC, NBL1S67Y was still 32-fold weaker than PRDC against BMP2. Taken together, this data suggests that alterations in the BMP binding epitope can partially account for differences in the potency of BMP inhibition within the DAN family.

Introduction

Bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs)3 define the largest subclass of proteins, consisting of roughly 20 unique members, belonging to the greater transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) superfamily of secreted cytokines. In general, BMP ligands exist as mature, disulfide-linked homodimers, showing significant structural conservation. During development, BMP signaling is important for directing cellular differentiation across numerous tissue and organ types, ranging from skeletal and kidney morphogenesis to mesodermal and neuronal patterning (1). Furthermore, these developmental programs are utilized during adulthood to promote tissue regeneration, repair, and homeostasis, most noted for their roles in bone remodeling (1–4).

In vivo, numerous protein families have evolved to either aid or antagonize BMP signaling at each level of the pathway (3). The most common of these mechanisms works through the action of secreted extracellular antagonists that function to directly neutralize BMP ligands to inhibit signaling. The spatial and temporal interplay of BMP ligands with their secreted extracellular antagonists is critical to focus and fine-tune signaling for normal development and homeostasis, where misregulation of this balance causes or perpetuates innumerable different disease states, including osteoarthritis, several cancer phenotypes, diabetic kidney nephropathy, and pulmonary arterial hypertension (3, 5–11). Although BMP ligands are structurally similar, their extracellular antagonists are highly diverse, spanning large multidomain proteins, as seen for the Follistatin and Chordin families of antagonists, to small, single domain proteins, such as Noggin and members of the DAN family (1, 3, 4, 12).

In general, extracellular BMP antagonists function through direct binding interactions, thus competing with the receptor binding motifs of the ligand as illustrated in the structures of Noggin, Follistatin, and a portion of Crossveinless-2 bound to specific BMP ligands (13–15). However, our understanding of DAN family-mediated antagonism remains underdeveloped, despite being the largest known family of BMP antagonists in vertebrates (12). Furthermore, based upon their characterized importance in numerous disease states, where different DAN proteins have been directly linked to the diseases mentioned above, there is a strong need to evaluate these proteins structurally and functionally to aid in future therapeutic design processes to restore the proper balance of BMP signaling (12).

In recent years, two structures of DAN family members have been published, including PRDC and Sclerostin (SOST) (16–18). Although the structure of SOST represents the first of any DAN family member, SOST lacks any significant ability to antagonize BMPs, thus providing limited information in this regard (17–20). In 2013, biochemical studies based on the structure of PRDC lead to identification of a significant portion of its BMP binding epitope (16). However, it is not known how these results translate to the remainder of the DAN family. To complicate matters, the DAN family consists of 7 different members that all show unique differences in BMP affinity and specificity, in addition to identified non-canonical roles (such as in Wnt and VEGF signaling) (12). For example, several antagonists have been implicated with very high affinity toward specific, canonical BMP ligands (BMP2, BMP4, and BMP7), including PRDC, Gremlin, and Coco (3, 12). On the other hand, SOST and USAG-1 have been somewhat enigmatic in the literature in terms of BMP inhibition (3, 12). For these two members, although not conclusive, it is likely that they function as moderate to weak inhibitors of BMP signaling, where they maintain the unique ability to directly antagonize Wnt signaling (21–24). Curiously, antagonists such as NBL1 (also known as Dan) lie between these two extremes, showing the ability to inhibit BMP signaling, albeit with much reduced potency (25). Therefore, to better understand how these differences arise, we sought to characterize the structure of NBL1 in relationship to its activity as a BMP antagonist.

NBL1 was originally identified based upon its potential activity as a suppressor of tumorigenicity in a neuroblastoma cell line (26, 27). Following this, the protein was suggested to play roles in regulating the cell cycle, specifically in the G1/S transition (28). In later studies, NBL1 was shown to have anti-BMP activity both in vitro and in vivo (25, 29–31). Since then, NBL1 has been implemented in numerous biological and in vitro assays as a BMP antagonist, where the majority of its functionality and expression have been linked to neurological roles and development, including observed expression patterns in developing forebrain and neural crest tissues (32–34). Furthermore, NBL1 has been shown to have the unique ability to induce mouse embryonic stem cells toward neuronal type lineages upon exogenous treatment with the protein (35). Despite this, the specificity of NBL1, as well as other DAN family members, is a topic of debate, where NBL1 has been shown in different instances to be a strong BMP2, BMP4, and BMP7 antagonist and a weak GDF5, GDF6, and GDF7 antagonist, or vice versa (25, 29, 31, 34). Therefore, to help fill these gaps in our understanding, we sought to determine the specificity of NBL1 although trying to undermine what features in NBL1 make it a unique and mild BMP antagonist in comparison to both stronger and weaker DAN family members, including PRDC (strong) and SOST (weak). Toward this goal, we present the crystal structure of NBL1. With this structure, in addition to our previous studies on PRDC, we have begun to address how differences in specificity for unique BMP ligands are derived. Using this information, we hope to aid in the mechanistic understanding of DAN-mediated BMP regulation.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Protein Expression and Purification of NBL1 and PRDC

Purified NBL1 was generated utilizing our previously published protocol (25). In short, CHO-DG44 cells were transfected using the pOptovec plasmid with a C-terminal prescission protease (PP)-Myc-His tag and expression was optimized and selected using increasing concentrations of methotrexate. Conditioned medium containing NBL1-PP-Myc-His was applied to a nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid column, bound, and eluted with 500 mm imidazole according to the manufacturer's protocol. Enriched protein was then digested using PP at 4 °C for 24 h to remove the Myc-His tag. Following digestion, NBL1 was purified to homogeneity using SEC on a Superdex S75 HR 10/300 column (GE Biosciences) in 20 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, 500 mm NaCl. The resulting full-length NBL1 protein has the additional amino acids LEVLFQ added to its C terminus. For purification of the shortened C-terminal NBL1 construct (NBL1ΔC), purified NBL1 was treated for 24 h at 37 °C with carboxypeptidase B in 25 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.65, 0.1 m NaCl as described in the manufacturer's protocol (Worthington). Following digestion, protein was purified to homogeneity using SEC on a Superdex S75 HR 10/300 column as described for the full-length protein. For the production and purification of the corresponding NBL1 mutants, amino acid mutations were generated in the parent plasmid using the typical protocol for QuikChange mutagenesis. The plasmids were then transiently transfected into HEK293T cells for expression. Conditioned medium was harvested after 9 days and purified using the outlined purification scheme for the wild-type protein. PRDC was expressed in bacteria, oxidatively refolded, purified, and assayed for activity as has been previously described (16, 25, 36).

X-ray Structure Determination and Refinement of NBL1

NBL1ΔC crystals were grown by hanging-drop vapor diffusion using crystal condition H4 from the Morpheus screen (Molecular Dimensions). This condition is composed of 12.5% (w/v) PEG 1000, 12.5% (w/v) PEG 3350, 12.5% (v/v) 2-methyl-2,4-pentanediol (MPD), 0.1 MES/imidazole, pH 6.5, and 0.02 m of several amino acids (sodium l-glutamate, dl-alanine, glycine, dl-lysine HCl, dl-serine). Diffraction data were collected at the Advanced Photon Source (21ID-F LS-CAT) at Argonne National Laboratory and processed as previously described (16). Phasing was performed by molecular replacement using Phaser and the CCP4 suite with the monomeric and dimeric structures of PRDC (Protein Data BAnk code 4JPH).

Luciferase Reporter Assay

A BMP responsive luciferase reporter osteoblast cell line, kindly provided by Dr. Amitabha Bandyopadhyay, was used to measure BMP activity and inhibition. Briefly, cells were maintained in α-minimal essential medium, 10% FBS, 100 μg/ml of hygromycin B, 100 units/ml of penicillin, and 100 μg/ml of streptomycin. Cells were plated in a 96-well plate and medium was changed to DMEM/Hi Glucose the following morning. Four hours later, protein was added to the cells and incubated for 3 h, at which time cells were lysed and luminescence was read using a BioTek Synergy H1 plate reader. Data were normalized by scaling the highest point in each data set to 100% with 0% representing a complete absence of a BMP/GDF response. Fit curves and IC50 values were calculated using the Prism software package. Statistical significance was determined using the Student's t test.

Xenopus Embryo BMP Target Gene Assay

Embryo manipulations and microinjections were performed as previously described and staged according to the normal table of development for X. laevis (16, 25). To assay the in vivo BMP-inhibition activity of NBL1, NBL1 mutants, and PRDC, we injected the blastocoel cavities of stage 9 Xenopus embryos with 40 nl of 0.5, 2, or 10 μm purified protein in PBS with 0.1% BSA. Embryos were then cultured at room temperature until stage 20, fixed overnight at 4 °C in MEMFA (a solution at pH 7.4 containing 3.8% formaldehyde, 0.15 m MOPS, 2 mm EGTA, 1 mm MgSO4), and analyzed for expression of the BMP target gene sizzled via whole mount in situ hybridization as previously described (16, 25). The antisense sizzled in situ probe was prepared using T7 RNA polymerase with SalI-linearized pCMV-Sport6-sizzled plasmid template (IMAGE clone 4057152 obtained from Open Biosystems). Some injected embryos were allowed to develop until stage 35, where they were subsequently scored for posterior axial truncations using the well established dorsoanterior index (37).

RESULTS

Activity and Specificity of NBL1

In previous studies, we have shown the ability to produce the full-length NBL1 protein from stable mammalian expression in high yield (25). Using this protein, we sought to better characterize via luciferase reporter assay the affinity and specificity of NBL1 toward several unique and different BMP ligands, including BMP2, BMP7, and GDF5. Furthermore, we wanted to validate NBL1 as a modest/mild antagonist of BMP signaling and compare it to both stronger (PRDC) and weaker (SOST) DAN family antagonists.

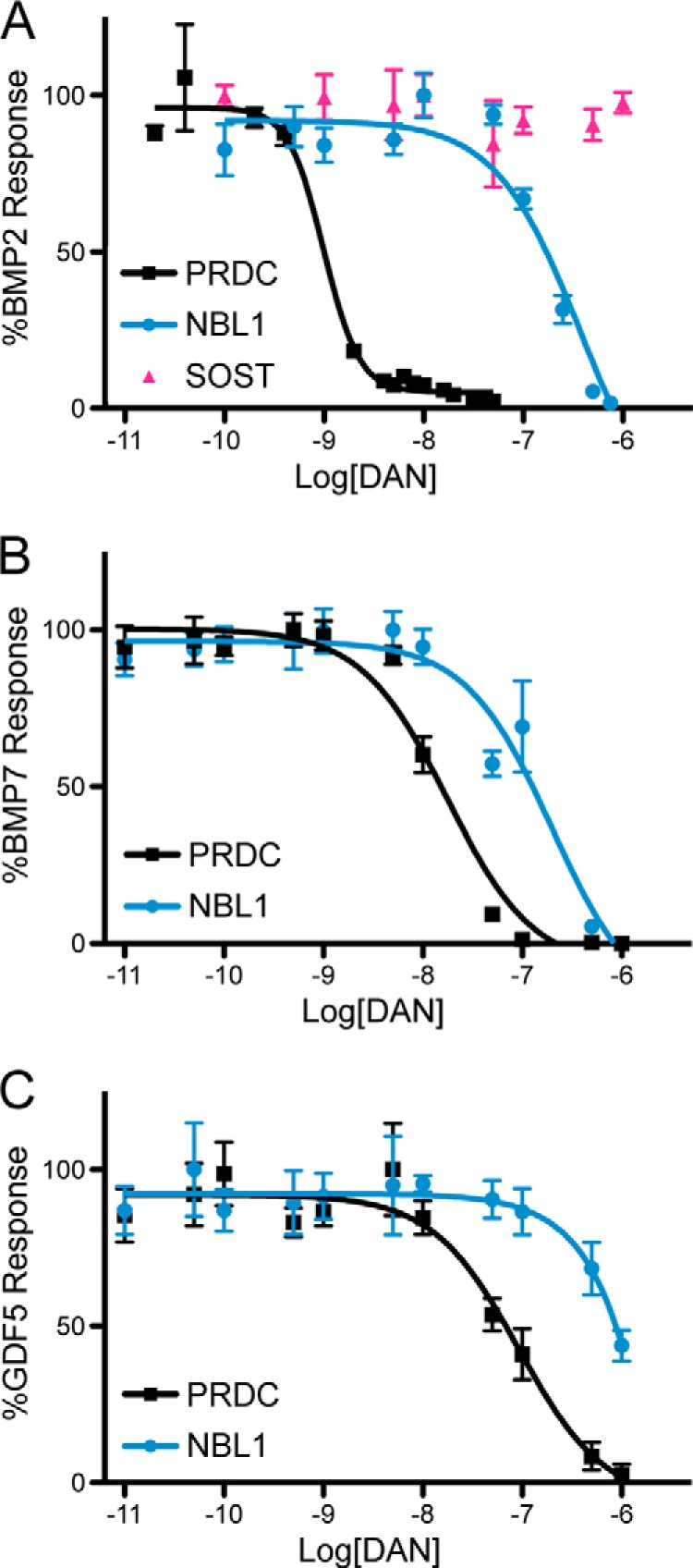

When tested against BMP2, NBL1 (177 nm IC50) is a much weaker antagonist than PRDC (0.5 nm IC50), being 380-fold less potent in comparison (Fig. 1A). On the other hand, SOST lacks any substantial ability to inhibit BMP2 signaling, where an IC50 value cannot be approximated (Fig. 1A). Taken together, this implies that NBL1 is a moderate antagonist of BMP2 within the DAN family.

FIGURE 1.

Comparison of BMP specificity and inhibition for PRDC and NBL1. PRDC and NBL1 (SOST only tested in A) were titrated against 1 nm BMP2 (A), 3.2 nm BMP7 (B), and 3.7 nm GDF5 (C) using a BMP responsive osteoblast cell line (BRITER) to measure inhibition and determine relative IC50 values. Experiments were performed in triplicate and the curves represent the average of three individual experiments (error bars represent ±S.E.).

To help understand the differences in specificity and affinity between NBL1 and PRDC, we tested their abilities to inhibit both BMP7 and GDF5. These results clearly show that NBL1, in all cases, is a much weaker antagonist in comparison to PRDC. For BMP7, NBL1 showed an IC50 value of 199 nm, whereas PRDC exhibited an IC50 of 18 nm (Fig. 1B). Although NBL1 is still much weaker at antagonizing BMP7 than PRDC, being 11-fold less effective, this gap in activity is significantly reduced in comparison to BMP2. Furthermore, NBL1 appears to antagonize BMP2 and BMP7 with similar potency, whereas PRDC clearly inhibits BMP2 signaling more effectively (Fig. 1, A and B). When testing these proteins against GDF5, however, both proteins show a significant decrease in inhibition, where PRDC gives an IC50 of 92 nm and NBL1 gives an IC50 of greater than 10 μm (Fig. 1C). In combination, the affinity of PRDC can be represented by BMP2 > BMP7 > GDF5, all being within physiological range. For NBL1, this scheme is BMP2 ≈ BMP7 ≫ GDF5, with inhibition of GDF5 likely not being physiological. Based upon our recent structure/function studies on PRDC, where we identified a significant portion of the BMP binding epitope of the protein, we sought to better understand how differences in affinity and specificity arise for BMP ligands across the DAN family by continuing our structure/function studies on NBL1 (16).

Crystallization of Full-length NBL1

For NBL1, and all DAN family antagonists, the protein can be dissected into three main regions: 1) the N terminus, 2) the functional DAN domain, and 3) the C terminus (Fig. 2A). Briefly, conservation across the family is based upon similar spacing of eight cysteines that have been shown in PRDC and SOST to form four intra-molecular disulfide bonds within the DAN domain (12). Furthermore, conservation within the two termini is very sparse, being highly variable across the family and the most variable across species (reviewed in Ref. 12). Members SOST and USAG-1 contain only eight conserved cysteines, representing the most basic scaffold for this family of proteins. For a number of members, however, including PRDC and Gremlin, there is an additional cysteine present in the DAN domain, which was originally believed to aid in dimer formation, similar to the BMP ligands (12, 38). In contrast, NBL1 contains 10 cysteines within the DAN domain, a feature unique to this protein.

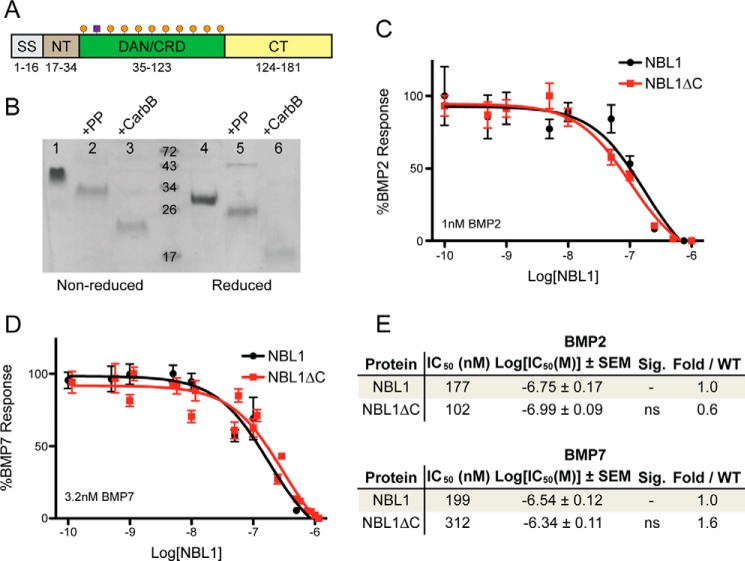

FIGURE 2.

Comparison of NBL1 and NBL1ΔC. A, schematic of the NBL1 protein. The protein can be separated into 4 regions: the signal sequence (SS), N terminus (NT), cysteine-rich or DAN domain (DAN/CRD), and C terminus (CT). Numbers under the diagram represent the amino acids in NBL1 composing each region. Orange circles represent cysteines and the purple box represents glycosylation. B, SDS-PAGE gel of purified NBL1 with the Myc-His6 tag used for purification in lanes 1 and 4, full-length NBL1 after remove of the purification tag using Prescission Protease (PP) in lanes 2 and 5, and NBL1 after cleavage using carboxypeptidase B (NBL1ΔC) in lanes 3 and 6. Proteins in lanes 4–6 were reduced using 10 mm β-mercaptoethanol. C and D, luciferase reporter assay testing the activity of NBL1 and NBL1ΔC against (C) 1 nm BMP2 and (D) 3.2 nm BMP7. E, table summarizing inhibition data for NBL1 and NBL1ΔC. IC50 values and significance were determined from Luciferase reporter assays using the Prism software package. NS, not significant based upon a p value of 0.05.

Previously, we showed that both PRDC and NBL1, despite containing additional cysteines, do not form disulfide-linked dimers (25). However, we determined that PRDC formed functional dimers stabilized by strong non-covalent interactions, supported by the structure of PRDC (16). Despite this, there remains a number of structural questions regarding the NBL1 dimer and how it compares to the PRDC dimer.

Initially, we set out to determine the structure of the full-length NBL1 protein. However, crystallization proved intractable. Based upon available structural knowledge for PRDC and SOST, we hypothesized that the difficulty crystallizing NBL1 might arise from intrinsic flexibility within its N and C termini (16–18). Flexibility in the termini is readily apparent from our studies on the structure of PRDC, where a number of residues in the N terminus cannot be accounted for in electron density (16). Furthermore, the ensemble NMR structure of SOST shows significant variations in its N and C terminus, suggesting dynamic sampling of nearby conformational space within these regions (17). Because NBL1 has a very extended and lengthy C terminus and a short N terminus in comparison to other DAN family members, we sought methods to truncate the C terminus of NBL1 to make crystallization more tractable (Fig. 2A).

Limited Proteolysis of NBL1

Because a stable cell line producing high levels of NBL1 was available, a straightforward method for truncating NBL1 would be through limited proteolysis. Initially, we tested several different proteases for their ability to produce a stable fragment of NBL1, including carboxypeptidase B, carboxypeptidase Y, trypsin, and chymotrypsin (data not shown). Following digestion at 37 °C for 24 h, proteins were analyzed by reducing and non-reducing SDS-PAGE. Only carboxypeptidase B showed stable fragment production that was roughly 6 kDa smaller in size as compared with the full-length construct (Fig. 2B). Furthermore, analysis by reducing SDS-PAGE revealed that no internal cleavage had occurred, suggesting that only the C terminus of the protein had been proteolyzed (Fig. 2B).

Following these initial results, we scaled up digestion of full-length NBL1 and purified the fragment to homogeneity using SEC with a Superdex S75 HR 10/300 column. Mass spectrometry suggests that both purified short NBL1 (∼14.2 kDa) and full-length NBL1 (∼20.1 kDa) monomers were mildly heterogeneous, as expected based upon predicted N-linked glycosylation at a single asparagine residue (Asn39) (data not shown) (31). Furthermore, short NBL1 shows a slightly wider profile, with a Gaussian distribution spanning from ∼13 to ∼15 kDa, suggesting that cleavage was variable. Because carboxypeptidase B preferentially digests polypeptides from the C terminus, we predict these shortened fragments of NBL1 represent roughly the N terminus and the DAN domain with the majority of the C terminus removed. From this point forward, we will refer to this shortened construct of NBL1 as NBL1ΔC.

Prior to crystallization attempts with NBL1ΔC, we sought to determine whether NBL1ΔC activity was equivalent to wild-type NBL1. First, we tested the two proteins for the ability to inhibit BMP2 signaling via the luciferase reporter assay. These results clearly show that NBL1ΔC maintains most, if not all or more, of its antagonist phenotype when compared with the wild-type protein, where the C terminus appears dispensable for BMP2 inhibition (Fig. 2, C and E). Similar results were seen when NBL1ΔC was tested against BMP7; however, there was a slight decrease in activity when compared with full-length NBL1, although it was not statistically significant (Fig. 2, D and E). This supports that NBL1ΔC maintains the majority of its functional anti-BMP activity within its core DAN domain. Taken together, because NBL1ΔC showed similar functionality to the full-length protein toward both BMP2 and BMP7, we decided that this construct was suitable for crystallography.

Crystal Structure of NBL1ΔC

Where full-length NBL1 failed to form crystals, NBL1ΔC was readily crystallized. Single crystals were harvested and diffracted to 2.5 Å, where the structure was resolved by molecular replacement phasing using the structure of PRDC (Table 1) (16). Initial observations of the NBL1ΔC structure reveal that two monomers are present in the asymmetric unit. These two NBL1ΔC monomers come together to form a head-to-tail (or antiparallel), non-covalent dimer, formed by the interaction of two synonymous β-strands from each monomer, similar to PRDC (Fig. 3, A and B). Extending from the dimer interface of the protein, two N termini can be seen diverging away from the core DAN domains, suggesting that there is limited interaction between these two different regions. Overall, the dimer takes on a very arch-like morphology (roughly 29 Å in height and 88 Å in length) along the long axis of the protein, exposing large concave and convex surfaces (Fig. 3A).

TABLE 1.

X-ray diffraction data and refinement statistics

| NBL1ΔC (native)a | |

|---|---|

| Data collection | |

| Space group | P 41 21 2 |

| Unit cell dimensions | |

| a, b, c (Å) | 59.7, 59.7, 145.0 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90, 90, 90 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.95740 |

| Resolution (Å) | 2.5 (2.66–2.5) |

| Rmerge | 0.098 (1.38) |

| Rpim | 0.040 (0.57) |

| Mn (I/SD)b | 23.5 (2.4) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.7 (97.9) |

| Redundancy | 12.3 (12.4) |

| Refinement | |

| Resolution (Å) | 48.3–2.5 |

| No. reflections | 119,592 (12,775) |

| Rwork (%)/Rfree (%)c | 21.4/27.5 |

| B-factor (average) | 89.2 |

| Root mean square deviations from ideal geometry | |

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.041 |

| Bond angles (°) | 2.27 |

| Ramachandran plot | 154 (92.2%) Favored |

| 12 (7.2%) Allowed | |

| 1 (0.6%) Outliers | |

| Clashscore | 3.40 |

a Values in parentheses are for highest-resolution shell as defined in the resolution row.

b Mn (I/SD) defined as 〈merged〈Ih〉/SD(Ih)〉 ≈ signal/noise.

c Rfree calculated from 5% of initial total number of reflections.

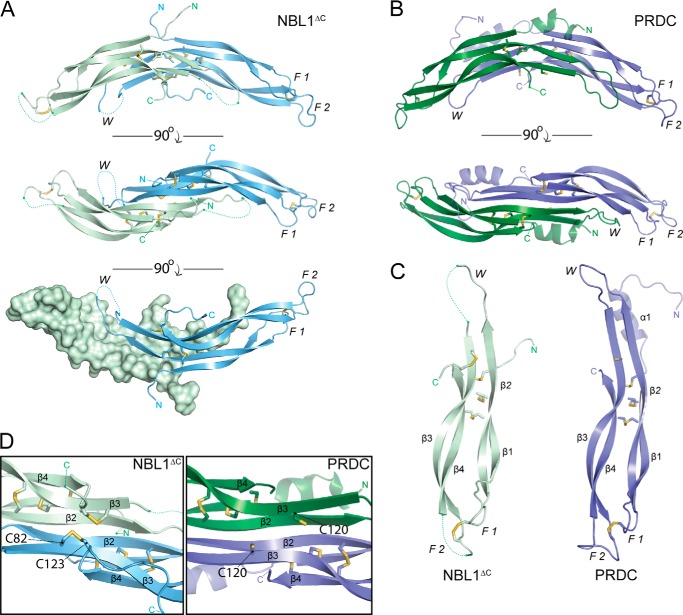

FIGURE 3.

Crystal structure of NBL1ΔC. A, ribbon representation of the NBL1ΔC dimer with the Chain A monomer shown in pale green and Chain B monomer shown in pale blue. Sticks represent disulfide bonds with sulfurs colored yellow-orange. Dotted lines represent areas that cannot be resolved in the electron density and connect amino acids according to the primary protein sequence. Different views (from top to bottom) show the dimer rotated 90° about the horizontal axis. F1, finger 1; F2, finger 2; W, wrist region. B, ribbon representation of the PRDC dimer crystal structure (Protein Data Bank code 4JPH, Ref. 16). C, comparison of the NBL1ΔC and PRDC monomer structures. β-Strands are labeled in each monomer (β1-β4) in order from the N terminus. D, view of the bottom, concave surfaces of NBL1ΔC (left) and PRDC (right), highlighting their cystine knots. As can be seen, the fifth disulfide bond in NBL1ΔC links the final cysteine of the protein to the synonymous free cysteine in PRDC and reiterates that these proteins do not form covalently attached dimers.

Taking a more detailed look at the NBL1ΔC protein structure, a number of interesting features can be identified. First, the overall fold of the NBL1ΔC monomers is very similar to that of PRDC and SOST, where a series of β-strands (β1-β4) within the DAN domain compose a growth factor-like fold (Fig. 3C) (16–18). This fold can be described in terms of hand, similar to BMP ligands, where the N terminus (Ala17-Trp34) leads into a concession of β-strands that form numerous intramolecular and antiparallel contacts, punctuated by three distinct loops. These loops mark the defining regions of the protein fold, where the area surrounding the first loop from the N terminus comprises finger 1 (F1) (Cys35-Gln62), the second and largest loop comprises the wrist region (W) (Cys63-Ser84), and the third loop comprises finger 2 (F2) (Cys85-Ala122) (Fig. 3, A and C). Upon dimerizing, the two fingers of each monomer point out in opposing directions, whereas the wrist regions stay more internal and in closer proximity to the dimer interface of the protein. Furthermore, the NBL1ΔC monomers maintain the defining four disulfide bonds that characterize the DAN family (Fig. 3, A and C) (12). Three of these intramolecular disulfide bonds come together to form a ring-like structure known as a cystine-knot motif within each monomer (Cys35-Cys85, Cys59-Cys118, and Cys63-Cys120). The fourth disulfide bond links F1 to F2 (Cys49-Cys99), differentiating the NBL1ΔC monomers, as well as the remaining DAN family members, from BMP and other growth factor monomers. Most unique to NBL1ΔC is the existence of a fifth intramolecular disulfide bond (Cys82-Cys123), not present in any other DAN family member, which links the C terminus of the protein to its concave surface (Fig. 3D) (12).

Overall, the final refined structure of NBL1ΔC shows positive electron density for the amino acids Asp30-Phe72, Val80-Gly101, and Val108-Lys125 in Chain A and Asp30-Pro69 and Ala77-Glu130 in Chain B, where amino acids outside of these regions were not resolved. Additionally, density can be seen extending from Asn39 indicating the residue is glycosylated.

Structural Analysis of NBL1ΔC and Comparison to PRDC

Looking at both the NBL1ΔC and PRDC structures, a number of similarities can be noted. First, both protein monomers maintain a highly similar architecture, showing a strong resemblance in terms of β-strand length as well as overall shape, supported by a root mean square deviation of 0.98 between their corresponding DAN domains (Fig. 3C). In addition, both protein dimers share the previously mentioned arch-like morphology (Fig. 3, A and B). In terms of dimerization, the mechanism facilitating this strong non-covalent interaction within PRDC or NBL1ΔC appears to be identical, where β2 within the wrist region of each protein is central to dimer formation (Fig. 3, A and B). More specifically, dimerization is stabilized by the formation of 10 hydrogen bonds between Cys59-Ser67 of one NBL1ΔC monomer with the reversed sequence in the opposing monomer, very similar to that seen for PRDC (16). Furthermore, roughly 1300 Å2 of buried surface area lies within the dimer interface of NBL1ΔC, being similar, albeit slightly less, than that seen for PRDC (16). Taken together, this supports the ability of these two antagonists to resist denaturation by upwards of 4 m urea (25).

Despite these similarities, NBL1ΔC and PRDC exhibit a number of structural differences. Most obviously, the secondary structure content in the N terminus of PRDC is substantially different when compared with NBL1ΔC (Fig. 3, A–C). For NBL1ΔC, a short, random coil N terminus can be seen and does not appear to be interacting with the core DAN domain of the protein (Fig. 3A). This feature is very similar to SOST, which shows little to no interaction between its random coil N terminus and DAN domains (17). PRDC, on the other hand, shows a significant level of interaction between its two α-helical N termini and DAN domains (Fig. 3B) (16). Here the helix of PRDC shields the underlying hydrophobic residues lining its convex surface (16).

As stated above, NBL1ΔC (10 cysteines) can be contrasted from PRDC (9 cysteines) and SOST (8 cysteines) simply by the number of disulfide bonds and cysteines each contains, where NBL1ΔC forms five disulfide bonds, whereas PRDC and SOST only form four. In PRDC, although the architecture of the concave surface is very similar to NBL1ΔC, no disulfide bond can be formed as it lacks a 10th cysteine, leaving a lone free cysteine in this region of the DAN domain (Fig. 3D). Looking at the monomer structures of the proteins, it can be seen that the curvature in β3 and β4 of NBL1 is different from that of PRDC, likely due to the formation of the fifth disulfide bond (Fig. 3C). As such, this difference in curvature within β3 and β4 causes the PRDC and NBL1ΔC dimers to have somewhat different morphology, where the NBL1 dimer is more curved and S-like in nature when compared with PRDC, which is more linear (Fig. 3, A and B). Because of this curvature, the wrist region of one monomer and finger 1 of the opposing monomer are in closer proximity to one another when compared with PRDC, possibly increasing the shielding of the dimer interface and wrist region of NBL1ΔC. Although speculative, these differences in dimerization might account for some of the variability seen in activity between these two proteins.

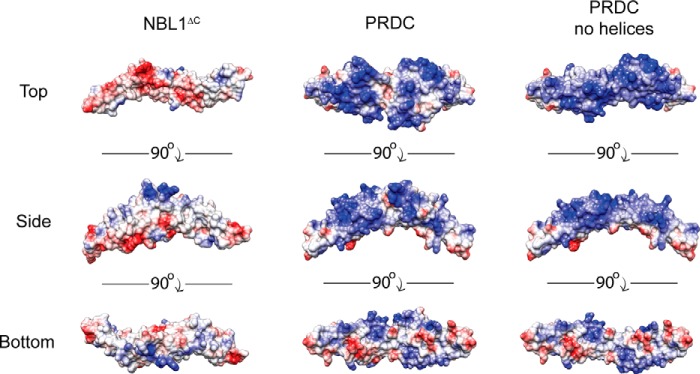

Last, PRDC and NBL1ΔC show significant differences in their ability to bind to heparin/heparan oligosaccharides (12, 16). When tested, NBL1 shows no affinity for binding to heparin/heparan oligosaccharides immobilized for affinity chromatography (data not shown). PRDC, on the other hand, has a very strong and robust affinity for heparin/heparan, requiring at least 650 mm NaCl to be eluted (16). Looking at the surface charges of NBL1ΔC and PRDC, generated using APBS, significant differences can be seen. For PRDC, nearly the entire the convex surface of the protein, with or without its N terminus, contains numerous regions of localized positive charge, having a theoretical pI of 9.3 (Fig. 4). The surface of NBL1ΔC, on the other hand, shows no regions of localized positive charge, being much more neutral and acidic in character (theoretical pI of 5.0), explaining the observed differences in heparin binding affinity (Fig. 4).

FIGURE 4.

Comparison of NBL1ΔC and PRDC electrostatics. Three views of NBL1ΔC, PRDC, and PRDC lacking its N-terminal helices, depicting the electrostatic surface potential of these proteins from the top, bottom, and side perspectives. Surface potential was calculated using APBS and the proteins are colored based on a scale from −10 to 10 kbT/ec (red to blue).

Functional Analysis of NBL1

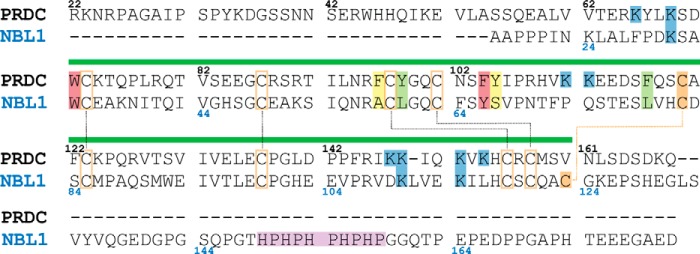

As stated above, there is significant divergence in functional antagonism of BMP ligands across the DAN family, where PRDC acts as a very potent antagonist and NBL1 functions very modestly in comparison (12). Therefore, to better understand where affinity for BMP ligands is imparted within NBL1, we generated several point mutations in NBL1. Amino acids were selected based upon a multiple alignment with PRDC, where we previously identified several residues lining the convex surface of PRDC to be important for BMP antagonism (Figs. 5 and 6A) (16). Four of these residues were conserved in NBL1 (Trp34, Leu60, Tyr66, and Leu79) and were mutated to alanine to probe for loss-of-function phenotypes. Two positions were strikingly nonconserved, Ala58 and Ser67 (Phe and Tyr, respectively, in PRDC). Therefore, we tested the possibility that the reduced potency of BMP antagonism in NBL1 could be a result of these two changes in the BMP binding epitope. Hence, we generated PRDC-like versions of NBL1 by making both A58F and S67Y (Figs. 5 and 6, A and B).

FIGURE 5.

Sequence alignment of NBL1 and PRDC. Alignment of the mouse PRDC (top) and human NBL1 (bottom) primary sequences (excluding signaling sequences). Numbers represent the amino acid for the corresponding antagonist (black for PRDC and blue for NBL1). Green bar over the alignment indicates the location of the DAN domain. Black dotted lines show disulfide bonds shared between both proteins. Orange dotted line represents the unique fifth disulfide bond present in NBL1. Lysines highlighted in blue are suggested to be important for heparin binding. Histidine-proline repeat in the C terminus of NBL1, believed to be important for metal binding, is highlighted in purple. Cysteines are highlighted orange. Amino acids highlighted in green, yellow, and red have been shown to be important for PRDC to bind to BMP2. Those highlighted in yellow are not conserved between PRDC and NBL1, whereas those in green and red are partially or well conserved, respectively.

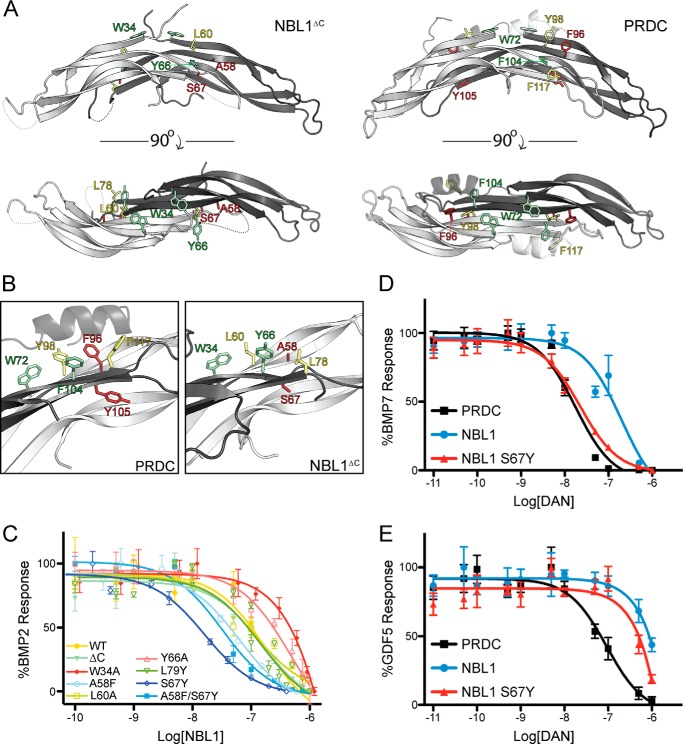

FIGURE 6.

Mutagenesis studies on NBL1. Ribbon representation of NBL1ΔC (A) and PRDC (B) showing amino acids (stick representation) selected for our mutagenesis studies based upon data obtained for characterizing the PRDC BMP-binding epitope. Each of these amino acids in a previous study was found to be important for mediating BMP inhibition in PRDC. Residues selected for mutagenesis that are poorly conserved between NBL1 and PRDC and colored in red, whereas those that are moderately and completely conserved are depicted in yellow and green, respectively. B, close up view of the residues selected for these studies and depicting the known portion of the PRDC BMP-binding epitope. C, luciferase reporter assay showing titration of various NBL1 mutants against 1 nm BMP2. The wild-type NBL1 protein and mutants with similar IC50 values are colored green to yellow, whereas those that resulted in reduction of inhibition compared with wild-type are colored red and those that result in improved inhibition are colored blue. D and E, luciferase reporter assay results comparing the activities of PRDC, NBL1 and NBL1S67Y when titrated against 3.2 nm BMP7 (D) and 3.7 nm GDF5 (E).

When tested exogenously against 1 nm BMP2 via luciferase reporter assay, two of the mutants (L60A and L79A) showed ambiguous or little change in activity as compared with wild-type (Fig. 6C and Table 2). However, W34A (3900 nm IC50) and Y66A (477 nm IC50) showed a substantial reduction in their ability to inhibit BMP2 signaling, with roughly a 2.7- and 22-fold reduction in inhibition compared with wild-type, respectively (Fig. 6C and Table 2). Interestingly, both PRDC-like mutants, A58F (63 nm IC50) and S67Y (16 nm IC50), were much more potent BMP2 antagonists than wild-type NBL1 (Fig. 6C and Table 2). For the S67Y mutation, the IC50 value approaches levels substantially closer to that of PRDC, only being roughly 32-fold less effective as compared with 380-fold weaker for the wild-type NBL1 protein. This data suggests that the location of the BMP binding epitopes between PRDC and NBL1 are likely very similar, where amino acid differences can account for a substantial amount of the variability between their corresponding activities.

TABLE 2.

Analysis of NBL1 mutants via luciferase reporter assay

Luciferase reporter assay was performed with 1 nm BMP2.

| NBL1 mutant | IC50 | Log[IC50(m)] ± S.E.a | Significanceb | Reductionc | Increased |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nm | fold | ||||

| WT | 177 | −6.75 ± 0.17 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| ΔC | 159 | −6.80 ± 0.12 | NSe | 0.66 | 1.52 |

| W34A | 3900 | −5.41 ± 0.60 | Yesf | 4.16 | 0.24 |

| Y66A | 650 | −6.32 ± 0.21 | Yesg | 3.42 | 0.29 |

| L60A | 160 | −6.94 ± 0.10 | NS | 0.84 | 1.19 |

| L79A | 170 | −6.84 ± 0.10 | NS | 0.89 | 1.12 |

| A58F | 70 | −7.20 ± 0.12 | Yesf | 0.37 | 2.71 |

| S67Y | 22 | −7.79 ± 0.08 | Yesf | 0.12 | 8.64 |

| A58F/S67Y | 27 | −7.49 ± 0.07 | Yesf | 0.14 | 7.04 |

a S.E., standard error of the mean. Experiments were performed in triplicate.

b Significance measured using Student's t test against WT.

c Represents fold decrease in BMP2 inhibition (WT/mutant).

d Represents fold increase in BMP2 inhibition (mutant/WT).

e NS, not significant.

f p value of 0.05.

g p value of 0.1.

To expand upon this finding, we decided to test whether or not the NBL1 gain-of-function mutant, S67Y, had any affect on the ability of the protein to inhibit other BMP ligands, specifically BMP7 and GDF5. When tested against BMP7, S67Y enhanced the activity of NBL1 to an IC50 of 23 nm, accounting for a roughly 9-fold increase in inhibition against wild-type (Fig. 6D and Table 3). Interestingly, S67Y and PRDC inhibit BMP7 with similar potency and nearly identical IC50 values. However, when the S67Y mutant was tested against GDF5, no significant increase in inhibition was observed as both NBL1 and S67Y have an IC50 in the mid-micromolar range (Fig. 6D and Table 3). PRDC, on the other hand, antagonizes GDF5 with an IC50 of 92 nm, indicating that S67Y did not increase NBL1 antagonism of GDF5. Taken together, these results suggest that a tyrosine at the 67th amino acid position in NBL1 and the synonymous position in PRDC is important for promoting BMP antagonism toward ligands BMP2 and BMP7 (16). Interestingly, this data also suggests that different regions or epitopes may be necessary to antagonize different BMP ligands, as the S67Y had no significant affect on GDF5 inhibition.

TABLE 3.

Comparison of NBL1, NBL1, and PRDC for BMP2, BMP7, and GDF5 inhibition

Luciferase reporter assay was performed with 1 nm BMP2, 3.2 nm BMP7, or 3.7 nm GDF5.

| Protein | IC50 | Log[IC50(m)] ± S.E.a | Significanceb | Fold/PRDCc |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| nm | ||||

| BMP2 | ||||

| PRDC | 0.5 | −9.00 ± 0.05 | 1.0 | |

| NBL1 | 177 | −6.75 ± 0.17 | Yesd | 380.0 |

| NBL1 S67Y | 16 | −7.79 ± 0.08 | Yesd | 32.0 |

| BMP7 | ||||

| PRDC | 18 | −7.76 ± 0.08 | 1.0 | |

| NBL1 | 199 | −6.70 ± 0.14 | Yesd | 11.1 |

| NBL1 S67Y | 23 | −7.65 ± 0.10 | NSe | 1.3 |

| GDF5 | ||||

| PRDC | 92 | −7.04 ± 0.15 | 1 | |

| NBL1 | >10,000 | NCf | NC | NC |

| NBL1 S67Y | >10,000 | NC | NC | NC |

a S.E., standard error of the mean. Experiments were performed in triplicate.

b Significance measured using Student's t-test against PRDC.

c Fold ratio over PRDC inhibition (protein/PRDC).

d p value of 0.05.

e NS, not significant.

f NC, not calculable.

In Vivo Analysis of NBL1

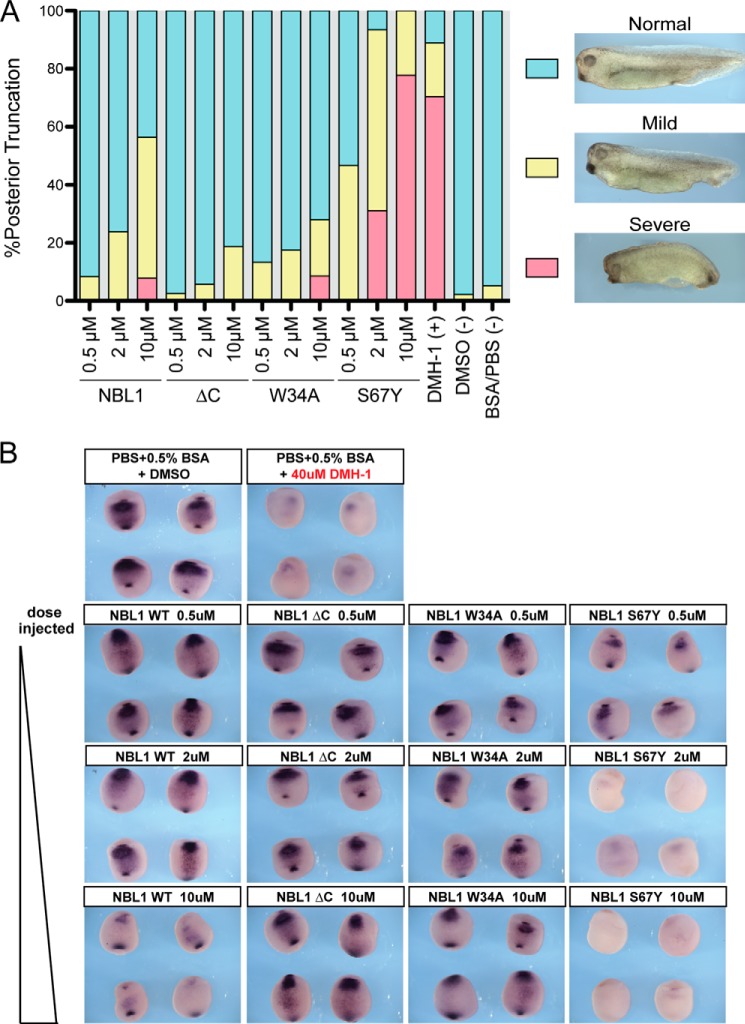

Last, we wanted to confirm our above findings in a more biologically relevant assay. To do this, we utilized developing Xenopus embryos to determine how each protein mutant affects BMP-dependent dorsal-ventral patterning, as we have previously published for an analysis of PRDC (16, 25). Briefly, axial patterning of Xenopus embryos is regulated by endogenous BMP4 and BMP7 ligands, which promote a ventral mesodermal fate in a dose-dependent manner (39). The experimental introduction of BMP antagonists into the embryo suppresses endogenous BMP activity, resulting in reduced BMP target gene expression and a stereotypical loss of ventral-posterior structures such as the tail. Using this assay to measure the bioactivity of the various NBL1 mutants, we injected purified protein at three concentrations (0.5, 2, and 10 μm) into the blastocoel cavity of stage 9 embyos (just prior to BMP-mediated patterning). We then assayed the resulting embryos by in situ hybridization at stage 20 for changes in expression of the direct BMP-target gene sizzled, and at stage 35 to assess morphological changes in axial structures, which can be quantified using a well established dorsoanterior index.

In this assay, exposure of the embryos to a strong BMP signaling inhibitor (e.g. the BMP receptor kinase inhibitor, DMH-1) results in severe defects in axial elongation and reduced sizzled mRNA expression (Fig. 7). In contrast, wild-type NBL1 and NBL1ΔC exhibit only mild BMP inhibition, with only modest posterior truncations and slight reductions in sizzled expression at the highest concentration (10 μm) (Fig. 7). However, when compared with wild-type protein, NBL1ΔC shows a slightly reduced ability to inhibit BMP signaling, as seen by their relative sizzled expression at 10 μm (Fig. 7). Consistent with our luciferase reporter data, the W34A loss-of-function mutation showed a weaker phenotype in comparison to wild-type NBL1 in both Xenopus experiments (Fig. 7). In contrast, the gain-of-function S67Y mutant showed a much stronger BMP inhibitory phenotype, with severe axial truncations and an almost complete loss of sizzled expression at the 2 and 10 μm concentrations, closely matching the DMH-1 positive control (Fig. 7). Thus, in this in vivo Xenopus assay, the S67Y mutant shows much stronger BMP inhibition than wild-type NBL1.

FIGURE 7.

Analysis of NBL1 and NBL1 mutants in vivo. In vivo BMP inhibition activity of NBL1 and various mutants tested during Xenopus embryo development. The purified proteins (0.5, 2, and 10 μm) were injected into the blastocoel cavity of stage 9 embryos. A, bar graph represents embryos that were scored for defects in BMP-dependent axial development at stage 35 using the standard dorsoanterior index and classified into different subgroups based upon the severity of posterior truncation. Each bar represents 100% percent of the embryos tested where cyan represents the percent of the population with a normal phenotype, yellow represents a mild phenotype (mild tail truncation), and red represents a severe axial truncation. Images show representative examples of each described phenotype. B, embryos at stage 20 (ventral views) were evaluated by in situ hybridization for mRNA expression of the direct BMP-target gene sizzled. In control embryos sizzled expression is detected in the ventral mesoderm as a result of endogenous BMP signaling (BSA/PBS control), whereas strong inhibition of endogenous BMP signaling results in very little to no sizzled expression (DMH-1 control). Each protein was tested in at least 3 separate injection experiments, with 80–100 embryos tested in total for each.

DISCUSSION

The DAN family of BMP antagonists shows a substantial amount of variance across its members in terms of their abilities to antagonize BMP signaling, despite sharing a common structural scaffold (12). For example, PRDC and Gremlin act as strong antagonists, NBL1 functions as a modest antagonist, and proteins such as SOST are weak or altogether non-functional (12). Furthermore, differences can be seen across the DAN family in terms of specificity. As shown above, PRDC antagonizes BMP2 > BMP7 > GDF5, all within expected physiological levels. However, NBL1 shows a slightly different dichotomy, with BMP2 ≈ BMP7 ≫ GDF5, where antagonism of BMP2 is about 380-fold weaker when compared with PRDC and roughly 11-fold weaker in regards to BMP7. Additionally, it appears that NBL1 lacks any physiological ability to antagonize GDF5, whereas BMP2 and BMP7 do not seem to be discriminated. Therefore, several questions arise: why does PRDC preferentially antagonize BMP2 over BMP7, why does NBL1 not recognize a difference between BMP2 and BMP7, and what determines which specific BMP ligands, including GDF5, are preferentially inhibited by these individual protein antagonists.

To gain a better understanding for how these differences in BMP inhibition and specificity arise across the DAN family, we have resolved the crystal structure of the NBL1 antagonist in a truncated, yet functionally active, form. With this structure, we sought to determine what differences in NBL1 differentiate it from PRDC and add to our understanding of the mechanisms characterizing the anti-BMP activity of the DAN family. As can be seen, the structure of NBL1ΔC shares a number of similarities with the PRDC structure, including an arch-like dimer-fold that is stabilized by a tandem, anti-parallel β-strands/sheets with 10-intermolecular disulfide bonds at its core, supporting their robustness under denaturing conditions.

NBL1ΔC also shows a number of differences as compared with PRDC. This includes, most noticeably, a lack in length and secondary structure within its N terminus. Although not resolved in our structure, the second most divergent area of interest between NBL1 and PRDC (and the rest of the DAN-family) lies in the C terminus of the protein. NBL1 has the largest C terminus across the entire family, which includes an interesting histidine-proline repeat that has been suggested to be important for metal binding (12, 40). Thus, NBL1 can bind to the nickel-chelated resin without an engineered His tag (40). Based upon our results, removal of this repeat, and nearly the entire C terminus of the protein, has no affect on BMP2 inhibition. However, truncation of the C terminus does appear to mildly affect the ability of the protein to inhibit BMP7, as seen by a 1.6-fold reduction in potency in the luciferase reporter assay, possibly explaining the mild differences in inhibition seen in our Xenopus assay experiments. Despite this, the majority of the anti-BMP activity within NBL1 appears to reside within its central DAN domain with the possibility that the C terminus could function to stabilize specific interactions with select BMP ligands.

Extending from this analysis, NBL1 stands out in the DAN family by containing the largest number of cysteines (10) and disulfide bridges (5) for any DAN family member. Interestingly, the odd, ninth cysteine of PRDC lies on the concave surface of the protein dimer. In NBL1ΔC, this synonymous cysteine forms a disulfide bond with the last and 10th cysteine in this protein, covalently attaching the beginning of the C terminus to β3. Although intriguing, the role that this extra disulfide bridge plays remains unknown. For PRDC, mutation of its 9th cysteine has no affect on BMP inhibition, function, or fold (25). For NBL1, no data are currently present to suggest a role for this extra disulfide bond.

Based upon our previous studies, we wanted to determine whether the BMP binding epitope identified in PRDC was conserved and synonymous within NBL1 (16). As shown above, we found that mutation of select, conserved amino acids in NBL1 resulted in significant reductions in BMP inhibition, including W34A and Y66A. Additionally, introduction of specific hydrophobic amino acids into NBL1, identified in the PRDC BMP binding epitope, greatly improved its functional activity. These mutations, A58F and, most significantly, S67Y, improved the ability of NBL1 to antagonize BMP2 signaling by nearly 3- and 11-fold, respectively. For S67Y, IC50 values approached 16 nm for BMP2, shrinking the gap in inhibition between NBL1 and PRDC from roughly 380- to 32-fold. Despite this increase, the gap in activity between PRDC and NBL1S67Y is still substantial, suggesting that additional features in PRDC, such as specific amino acids, the N terminus, C terminus, or electrostatic character, are necessary for higher affinity interactions.

In a different sense, the S67Y mutation in NBL1 was able to match PRDC in terms of activity toward BMP7, suggesting that the tyrosine and BMP binding epitope identified in our studies may entirely account for differences in functional antagonism toward this specific ligand (16). However, opposite to our findings for BMP2 and BMP7, when tested against GDF5, neither NBL1 nor NBL1 S67Y reached presumed physiological levels of inhibition as compared with PRDC, highlighting yet further functional differences between these two proteins. It is possible that GDF5 may utilize as of yet unidentified elements present within only select DAN family proteins, including PRDC. Stemming from our combined results for BMP2, BMP7, and GDF5 inhibition, the DAN family fold might be thought of as a scaffold, where modifications to this structure can lead to specific and defined differences in activity and specificity, including strong, weak, broad, and targeted inhibition. In this regard, PRDC likely functions as a high affinity, broad BMP antagonist, whereas NBL1 is more restricted to specific ligands, possibly accounting for necessary and different physiological roles.

Interestingly, the more potent BMP antagonist, PRDC, has high affinity toward heparin/heparan oligosaccharides, whereas the weaker antagonist, NBL1, has no affinity toward these molecules (16). This difference will localize PRDC to the cell surface, whereas NBL1 is free to diffuse into the surrounding milieu or serum. In principle, this parallels other TGF-β family antagonists, such as Follistatin and Follistatin-like 3 (FSTL3) (41). Although closely related, Follistatin binds heparin and is a stronger and broader antagonist, whereas FSTL3 does not bind heparin and is a weaker antagonist with more restricted ligand specificity (41). One could speculate that heparin binding spatially restricts the potent/broad antagonists to limit unwanted ligand antagonism. In contrast, antagonists that are free to diffuse are weaker and more specific, limiting off-target effects beyond their intended function. With this in mind, perhaps PRDC and NBL1 have differentially evolved, similar to Follistatin and FSTL3, to provide different inhibitory roles based upon context. One can envision that spatial restriction of PRDC, along with other heparin binding DAN family members, allows for the inhibition of broader and specific BMP signals within particular cell types expressing heparin, thus providing a framework for developing important gradients in SMAD activation. For NBL1, on the other hand, a lack of heparin binding could allow the protein to more readily diffuse to inhibit BMP signaling across a larger area, perhaps even across different tissues. As such, NBL1 may be more specific and less potent for particular ligands to avoid an over-inhibitory phenotype. Although these ideas are only speculative, elucidating these roles could provide clues for why these proteins are different and how these differences are phenotypically relevant.

In conclusion, the structure of NBL1 aids in our understanding of DAN family-mediated inhibition of BMP ligands, where we have expanded on how this family achieves inhibition. Furthermore, we are beginning to uncover how these proteins achieve differences in BMP specificity and activity, where it is possible that the conserved structure across this family could serve as a scaffold to impart differences in BMP inhibition or non-canonical roles (e.g. Wnt antagonism or VEGF agonism) (12). Ultimately, more work is needed to continue and better understand these differences, where expansion of this work into the rest of the DAN family will provide new and novel insights for activity. Additionally, studies revealing the structure of DAN-BMP complexes will reveal, furthermore, the true expanse of the BMP binding epitope and allow for more significant contributions to be made to aid in the future and hopeful design of anti-BMP or anti-DAN therapeutics.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Thompson and Zorn laboratories for critically reading the manuscript.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant R01 GM084186 from the NIGMS (to T. B. T.) and Grant R01 DK070858 from the NIDDK, and American Heart Association Grant 14PRE20480142 (to K. N.).

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (code 4X1J) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (http://wwpdb.org/).

- BMP

- bone morphogenetic protein

- Dan/DAN

- differential screening-selected gene aberrative in neuroblastoma

- NBL1

- neuroblastoma suppressor of tumorigenicity 1

- GDF

- growth and differentiation factor

- PRDC

- protein related to Dan and Cerberus

- PP

- prescission protease

- SEC

- size exclusion chromatography.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bragdon B., Moseychuk O., Saldanha S., King D., Julian J., Nohe A. (2011) Bone morphogenetic proteins: a critical review. Cell Signal. 23, 609–620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cai J., Pardali E., Sánchez-Duffhues G., ten Dijke P. (2012) BMP signaling in vascular diseases. FEBS Lett. 586, 1993–2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Walsh D. W., Godson C., Brazil D. P., Martin F. (2010) Extracellular BMP-antagonist regulation in development and disease: tied up in knots. Trends Cell Biol. 20, 244–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rider C. C., Mulloy B. (2010) Bone morphogenetic protein and growth differentiation factor cytokine families and their protein antagonists. Biochem. J. 429, 1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tardif G., Pelletier J.-P., Boileau C., Martel-Pelletier J. (2009) The BMP antagonists Follistatin and Gremlin in normal and early osteoarthritic cartilage: an immunohistochemical study. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 17, 263–270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gao H., Chakraborty G., Lee-Lim A. P., Mo Q., Decker M., Vonica A., Shen R., Brogi E., Brivanlou A. H., Giancotti F. G. (2012) The BMP inhibitor Coco reactivates breast cancer cells at lung metastatic sites. Cell 150, 764–779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tamminen J. A., Parviainen V., Rönty M., Wohl A. P. (2013) Gremlin-1 associates with Fibrillin microfibrils in vivo and regulates mesothelioma cell survival through transcription factor slug. Oncogenesis 10.1038/oncsis.2013.29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zhang Y., Zhang Q. (2009) Bone morphogenetic protein-7 and Gremlin: new emerging therapeutic targets for diabetic nephropathy. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 383, 1–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yanagita M. (2012) Inhibitors/antagonists of TGF-β system in kidney fibrosis. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 27, 3686–3691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wakefield L. M., Hill C. S. (2013) Beyond TGFβ: roles of other TGFβ superfamily members in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 13, 328–341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cahill E., Costello C. M., Rowan S. C., Harkin S., Howell K., Leonard M. O., Southwood M., Cummins E. P., Fitzpatrick S. F., Taylor C. T., Morrell N. W., Martin F., McLoughlin P. (2012) Gremlin plays a key role in the pathogenesis of pulmonary hypertension. Circulation 125, 920–930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nolan K., Thompson T. B. (2014) The DAN family: modulators of TGF-β signaling and beyond. Protein Sci. 23, 999–1012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Thompson T. B., Lerch T. F., Cook R. W., Woodruff T. K. (2005) The structure of the Follistatin: activin complex reveals antagonism of both type I and type II receptor binding. Dev. Cell 9, 535–543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Groppe J., Greenwald J., Wiater E., Rodriguez-Leon J., Economides A. N., Kwiatkowski W., Affolter M., Vale W. W., Izpisua Belmonte J. C., Choe S. (2002) Structural basis of BMP signalling inhibition by the cystine knot protein Noggin. Nature 420, 636–642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhang J.-L., Qiu L.-Y., Kotzsch A., Weidauer S., Patterson L., Hammerschmidt M., Sebald W., Mueller T. D. (2008) Crystal structure analysis reveals how the Chordin family member Crossveinless-2 blocks BMP-2 receptor binding. Dev. Cell. 14, 739–750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nolan K., Kattamuri C., Luedeke D. M., Deng X., Jagpal A., Zhang F., Linhardt R. J., Kenny A. P., Zorn A. M., Thompson T. B. (2013) Structure of protein related to Dan and Cerberus: insights into the mechanism of bone morphogenetic protein antagonism. Structure 21, 1417–1429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Veverka V., Henry A. J., Slocombe P. M., Ventom A., Mulloy B., Muskett F. W., Muzylak M., Greenslade K., Moore A., Zhang L., Gong J., Qian X., Paszty C., Taylor R. J., Robinson M. K., Carr M. D. (2009) Characterization of the structural features and interactions of sclerostin: molecular insight into a key regulator of Wnt-mediated bone formation. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 10890–10900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Weidauer S. E., Schmieder P., Beerbaum M., Schmitz W., Oschkinat H., Mueller T. D. (2009) NMR structure of the Wnt modulator protein Sclerostin. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 380, 160–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. van Bezooijen R. L., Svensson J. P., Eefting D., Visser A., van der Horst G., Karperien M., Quax P. H., Vrieling H., Papapoulos S. E., ten Dijke P., Löwik C. W. (2007) Wnt but not BMP signaling is involved in the inhibitory action of Sclerostin on BMP-stimulated bone formation. J. Bone Miner. Res. 22, 19–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. van Bezooijen R. L., ten Dijke P., Papapoulos S. E., Löwik C. W. (2005) SOST/Sclerostin, an osteocyte-derived negative regulator of bone formation. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 16, 319–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Semënov M., Tamai K., He X. (2005) SOST is a ligand for LRP5/LRP6 and a Wnt signaling inhibitor. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 26770–26775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ahn Y., Sanderson B. W., Klein O. D., Krumlauf R. (2010) Inhibition of Wnt signaling by Wise (Sostdc1) and negative feedback from Shh controls tooth number and patterning. Development 137, 3221–3231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lintern K. B., Guidato S., Rowe A., Saldanha J. W., Itasaki N. (2009) Characterization of Wise protein and its molecular mechanism to interact with both Wnt and BMP signals. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 23159–23168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bourhis E., Wang W., Tam C., Hwang J., Zhang Y., Spittler D., Huang O. W., Gong Y., Estevez A., Zilberleyb I. (2011) Wnt antagonists bind through a short peptide to the first β-propeller domain of LRP5/6. Structure 19, 1433–1442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kattamuri C., Luedeke D. M., Nolan K., Rankin S. A., Greis K. D., Zorn A. M., Thompson T. B. (2012) Members of the DAN family are BMP antagonists that form highly stable noncovalent dimers. J. Mol. Biol. 424, 313–327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ozaki T., Sakiyama S. (1994) Tumor-suppressive activity of N03 gene product in v-src-transformed rat 3Y1 fibroblasts. Cancer Res. 54, 646–648 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ozaki T., Enomoto H., Nakamura Y., Kondo K., Seki N., Ohira M., Nomura N., Ohki M., Nakagawara A., Sakiyama S. (1997) The genomic analysis of human DAN gene. DNA Cell Biol. 16, 1031–1039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ozaki T., Nakamura Y., Enomoto H., Hirose M., Sakiyama S. (1995) Overexpression of DAN gene product in normal rat fibroblasts causes a retardation of the entry into the S phase. Cancer Res. 55, 895–900 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dionne M. S., Skarnes W. C., Harland R. M. (2001) Mutation and analysis of dan, the founding member of the DAN family of transforming growth factor β antagonists. Mol. Cell Biol. 21, 636–643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pearce J. J., Penny G., Rossant J. (1999) A mouse Cerberus/Dan-related gene family. Dev. Biol. 209, 98–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hung W. T., Wu F. J., Wang C. J., Luo C. W. (2012) Dan (NBL1) specifically antagonizes BMP2 and BMP4 and modulates the actions of GDF9, BMP2, and BMP4 in the rat ovary 1. Biol. Reprod. 86, 158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Eimon P. M., Harland R. M. (2001) Xenopus Dan, a member of the Dan gene family of BMP antagonists, is expressed in derivatives of the cranial and trunk neural crest. Mech. Dev. 107, 187–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ohtori S., Yamamoto T., Ino H., Hanaoka E., Shinbo J., Ozaki T., Takada N., Nakamura Y., Chiba T., Nakagawara A. (2002) Differential screening-selected gene aberrative in neuroblastoma protein modulates inflammatory pain in the spinal dorsal horn. Neuroscience 110, 579–586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kim A. S., Pleasure S. J. (2003) Expression of the BMP antagonist Dan during murine forebrain development. Brain Res. Dev. Brain Res. 145, 159–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tanwar V., Bylund J. B., Hu J., Yan J., Walthall J. M. (2014) Gremlin 2 promotes differentiation of embryonic stem cells to atrial fate by activation of the JNK signaling pathway. Stem Cells 32, 1774–1788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kattamuri C., Luedeke D. M., Thompson T. B. (2012) Expression and purification of recombinant protein related to Dan and Cerberus (PRDC). Protein Expr. Purif. 82, 389–395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sive H. L., Grainger R. M., Harland R. M. (2000) Early Development of Xenopus laevis, 1st Ed., Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 38. Avsian-Kretchmer O., Hsueh A. J. (2004) Comparative genomic analysis of the eight-membered ring cystine knot-containing bone morphogenetic protein antagonists. Mol. Endocrinol. 18, 1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. De Robertis E. M., Kuroda H. (2004) Dorsal-ventral patterning and neural induction in Xenopus embryos. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 20, 285–308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kondo K., Ozaki T., Nakamura Y., Sakiyama S. (1995) DAN gene product has an affinity for Ni2+. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 216, 209–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sidis Y., Schneyer A. L., Keutmann H. T. (2005) Heparin and activin-binding determinants in Follistatin and FSTL3. Endocrinology 146, 130–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]