Background: LTC4S is required for Orai1/Orai3 LRC channel activation. However, the role of LTC4S in neointimal hyperplasia is unknown.

Results: LTC4S knockdown inhibited neointimal hyperplasia. Akt phosphorylation was decreased in injured arteries, and knockdown of Orai3 or LTC4S restored Akt phosphorylation.

Conclusion: LTC4S is required for neointimal hyperplasia.

Significance: LTC4S is a potential therapeutic target for vascular occlusive diseases.

Keywords: Calcium Channel, Calcium Release-activated Calcium Channel Protein 1 (ORAI1), Calcium Transport, Cardiovascular Disease, Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells, LTC4, Orai1, Orai3

Abstract

Leukotriene-C4 synthase (LTC4S) generates LTC4 from arachidonic acid metabolism. LTC4 is a proinflammatory factor that acts on plasma membrane cysteinyl leukotriene receptors. Recently, however, we showed that LTC4 was also a cytosolic second messenger that activated store-independent LTC4-regulated Ca2+ (LRC) channels encoded by Orai1/Orai3 heteromultimers in vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs). We showed that Orai3 and LRC currents were up-regulated in medial and neointimal VSMCs after vascular injury and that Orai3 knockdown inhibited LRC currents and neointimal hyperplasia. However, the role of LTC4S in neointima formation remains unknown. Here we show that LTC4S knockdown inhibited LRC currents in VSMCs. We performed in vivo experiments where rat left carotid arteries were injured using balloon angioplasty to cause neointimal hyperplasia. Neointima formation was associated with up-regulation of LTC4S protein expression in VSMCs. Inhibition of LTC4S expression in injured carotids by lentiviral particles encoding shRNA inhibited neointima formation and inward and outward vessel remodeling. LRC current activation did not cause nuclear factor for activated T cells (NFAT) nuclear translocation in VSMCs. Surprisingly, knockdown of either LTC4S or Orai3 yielded more robust and sustained Akt1 and Akt2 phosphorylation on Ser-473/Ser-474 upon serum stimulation. LTC4S and Orai3 knockdown inhibited VSMC migration in vitro with no effect on proliferation. Akt activity was suppressed in neointimal and medial VSMCs from injured vessels at 2 weeks postinjury but was restored when the up-regulation of either LTC4S or Orai3 was prevented by shRNA. We conclude that LTC4S and Orai3 altered Akt signaling to promote VSMC migration and neointima formation.

Introduction

Vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs)4 are the major constituents of the medial layer of vessels and play an important role in maintaining vessel integrity and controlling the vascular tone. VSMCs maintain an ability to dedifferentiate from a contractile excitable state to a synthetic proliferative nonexcitable state (1). Under physiological conditions, this in vivo property of VSMCs is important for vascular development and tissue repair. However, VSMC phenotypic modulation can also contribute to vascular diseases such as atherosclerosis, hypertension, and restenosis. A common animal model to study the molecular and cellular mechanisms involved in VSMC phenotypic modulation in vivo is the carotid artery balloon injury model in the rat. Typically, the left carotid vessel is injured by an inflated balloon that denudes the endothelium, distends the vessel wall, and causes mechanical injury to the VSMC medial layer; the right carotid artery from the same animal typically serves as a negative control.

Leukotriene-C4 synthase (LTC4S) is the key enzyme responsible for the synthesis of cysteinyl leukotrienes (CysLTs) through metabolism of arachidonic acid downstream of the 5-lipoxygenase pathway. CysLTs, namely LTC4, LTD4, and LTE4, which were originally described as smooth muscle constrictors (2), are now well known as major mediators of inflammatory responses in a variety of immune, airway, and vascular diseases such as arthritis, asthma, atherosclerosis, aneurysm, and myocardial infarction (3, 4). A 5-fold increase in LTC4S expression was found in bronchial biopsy specimens from patients with aspirin-intolerant asthma (5). This overexpression was caused by an A to C single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) at the −444 locus in the LTC4S gene promoter region (6). Interestingly, this −444A→C SNP in LTC4S gene promoter has been recently associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease and ischemic cerebrovascular disease in certain cohorts of patients (7–10). Naturally, the effects of CysLTs on cardiovascular diseases have been attributed to their autocrine and paracrine actions on plasma membrane CysLT receptors resulting in enhanced vascular inflammation and permeability and increased leukocyte chemotaxis with subsequent vascular tissue damage and/or degeneration. However, arachidonic acid has been appreciated for quite some time as a regulator of plasma membrane Ca2+-selective channels (11, 12). More specifically, our laboratory has recently reported a novel role for LTC4 in VSMCs distinct from its known proinflammatory capabilities. We showed that intracellular LTC4 in VSMCs could mediate Ca2+ entry across the plasma membrane through a store-independent pathway contributed by a heteromultimeric Orai1/Orai3 channel and regulated by the Ca2+ sensor STIM1 (13–17). Previous studies from our group and others have demonstrated the up-regulation of STIM1, Orai1, and Orai3 in synthetic cultured VSMCs and medial and neointimal VSMCs after vascular injury. Furthermore, molecular knockdown strategies aimed at preventing the up-regulation of these proteins in vivo inhibited neointimal hyperplasia (13, 18–24). Therefore, we sought to investigate the downstream pathways activated by LTC4-regulated Ca2+ (LRC) channels in VSMCs and to determine the potential up-regulation of LTC4S in VSMCs after vascular injury and the specific contribution of VSMC LTC4S to neointimal hyperplasia using the rat balloon injury model.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

The use of animals has been reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the State University of New York at Albany.

Primary VSMC Culture

Rat VSMCs were dispersed from adult male Sprague-Dawley rats as reported previously (13). Isolated cells were subcultured in medium containing 45% DMEM, 45% Ham's F-12, and 10% FBS supplemented by l-glutamine and antibiotic/antimycotic solution.

Production of Lentiviral Particles and Cell Infection

pGIPZ-GFP lentiviral vectors encoding shRNA against LTC4S (shLTC4S), Orai3 (shOrai3), or non-targeting shRNA (shNT) were purchased from Open Biosystems. Lentiviral particles were generated in HEK293FT cells (Invitrogen) that have been transfected by PolyJet (SignaGen) with plasmids pCMV-VSVG, pCMV-dR8.2, and pGIPZ-shRNA vector. The titers of the concentrated viral particles ranged from 106 to 107 infectious units/ml. VSMCs were seeded in 6-well plates at 30–40% density. Twenty-four hours after seeding, cells were infected for 24 h using 10–30 μl of lentiviral solution diluted in regular medium base with 10% heat-inactivated serum. We determined using Western blotting that the protein knockdown was optimal at 7 days postinfection. Thus, all in vitro experiments described herein were performed 7 days after lentiviral shRNA infection.

Proliferation and Migration Assays

For proliferation assays, VSMCs were infected with shLTC4S, shOrai3, or control shNT lentivirus. After 24 h, cells were counted using the trypan blue exclusion method, and equal numbers of cells were seeded in 6-well plates (5,000/well) and allowed to grow in complete medium. After 7 days, cells from each well were detached and counted; shLTC4S and shOrai3 conditions were normalized to shNT controls. For migration assays, VSMCs were seeded in 6-well plates on the 5th day postinfection. Once cells formed a monolayer, culture medium was exchanged by medium containing 0.4% FBS, and cells were incubated for another 24 h. A 100-μl pipette tip was used to scrape across the dish to make a wound, and debris was gently removed by washing the cell monolayer with PBS. Cells were subsequently incubated in culture medium containing 10% serum for 12 h. Using a marker pen to draw a line across the wound as a reference, bright field images of the wound around this reference line were captured at times 0 and 12 h. The surface areas of the wound were measured, and the extent of cell migration was determined using NIH ImageJ.

Balloon Injury of Rat Carotid Arteries

The protocol used has been described in great detail previously, including a recent video publication of this procedure (13, 24–26). Briefly, this survival surgery entails the use of a balloon guided by a catheter, which is inserted into a portion of the left carotid injury. The balloon is then inflated and used to mechanically injure the vessel. After injury, a small solution (30 μl) containing lentiviral particles encoding shRNA is injected intraluminally into the injured portion of the vessel, which is isolated by clamping. The lentiviral solution is kept in the vessel lumen for 30 min to allow viral transduction. The solution is then aspirated, the clamps are removed, and blood flow is restored. The rats are allowed to recover, and neointimal thickening due to VSMC proliferation typically peaks at 2 weeks postinjury.

Sections and Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) Staining

Rats were euthanized with CO2 14 days after balloon injury and lentiviral transduction. Injured left carotid arteries and control right carotid arteries were collected and embedded in optimal cutting temperature compound. Specimens were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C. Cross-sectioning was performed in a Leica CM3050 cryostat. H&E staining on sections was performed as described previously (24).

Protein Extraction and Western Blotting

Proteins from cultured VSMCs were extracted following a protocol described previously (24). For carotid arteries, proteins were extracted from carefully dissected medial and neointimal regions containing VSMCs. Briefly, freshly collected carotid arteries were cleaned in ice-cold PBS. Vessels were longitudinally cut open, and blood clots (if any) were removed from the lumen. For intact control vessels, the endothelial layer was removed by scratching the inner surface of vessel with a cell scraper. Medial and neointimal layers were separated from the adventitial layer by carefully peeling off adventitia. Tissues were wrapped up in a small piece of aluminum foil and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen. Frozen tissues were stored at −80 °C and subjected to protein extraction. Tissues were cut into small pieces and ground in a Teflon homogenizer with 120–180 μl of lysis buffer on ice. Protein concentrations were determined by BCA assay, and 10 μg of proteins/sample were loaded for SDS-PAGE. The resolved proteins in SDS-polyacrylamide gel (10–16%) were electrotransferred onto methanol-preactivated polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. After transfer, membranes were blocked overnight at 4 °C with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.05% Tween (TBST). Primary antibodies were diluted in TBST containing 1% BSA and incubated with membranes overnight at 4 °C. The source and working dilutions for each specific primary antibody are as follow: anti-LTC4S (H-100, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), 1:100; anti-Orai3 (Prosci CT), 1:125; anti-green fluorescent protein (GFP) (Abcam), 1:1000; anti-proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA), 1:1000; pan-anti-Akt (catalog number 9272) and anti-phospho-Akt (Ser-473 on Akt1; also recognizes Akt2 and Akt3 at corresponding residues; catalog number 9271), 1:1000 (Cell Signaling Technology); and anti-β-actin (Sigma), 1:5000. Membranes were developed in SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermo Scientific). Blotting images were taken by a Bio-Rad imager. Densitometry analysis was performed using NIH ImageJ.

In Vitro Akt Isoform Phosphorylation Assays

LTC4S or Orai3 were knocked down in cultured VSMCs using lentiviral particles encoding shRNAs. Non-targeting shRNA lentivirus was used as a control. Five days after infection, cells were seeded in 60-mm2 dishes. When cells reached 70–80% confluence, they were serum-starved by incubation in medium containing 0.4% FBS for 24 h. Then medium was replaced with the growth medium containing 10% FBS and incubated for 0.5, 1, 2, 4, or 24 h. The treated cells were lysed with 300 μl of sample buffer, and lysates were used for Western blotting. The non-stimulated cells were lysed and used as time 0 negative controls. The isoform-specific Akt and phospho-Akt antibodies used are anti-phospho-Akt1 (Ser-473) (D7F10) XP® rabbit mAb (Akt1-specific; 9018S); anti-phospho-Akt2 (Ser-474) (D3H2) rabbit mAb (Akt2-specific; 8599S); anti-Akt1 (2H10) mouse mAb (2967S), and anti-Akt2 (L79B2) mouse mAb (5239S); they were all purchased from Cell Signaling Technology.

Patch Clamp Electrophysiology

Conventional whole-cell patch clamp recordings were carried out exactly as described previously (27–32) using an Axopatch 200B patch clamp and Digidata 1440A digitizer (Axon Instruments) with a HumBug noise eliminator added in series. All experiments were performed at room temperature (20–25 °C). Resistances of filled glass pipettes were 3–4.5 megaohms when filled with the following pipette solution: 145 mm cesium methanesulfonate, 10 mm cesium 1,2-bis(2-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid, 5 mm CaCl2, 8 mm MgCl2, and 10 mm HEPES (pH adjusted to 7.2 with CsOH; free Ca2+ = 150 nm). Cells were washed with bath solution (135 mm sodium methanesulfonate, 10 mm CsCl, 1.2 mm MgSO4, 10 mm HEPES, 20 mm CaCl2, and 10 mm glucose (pH adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH)). Upon whole-cell patch clamp configuration, 250-ms voltage ramps (from +100 to −140 mV) were run every 2 s. The first divalent-free (DVF) bath exchange was made when current development was minimal to gauge background currents. When currents were fully activated by inclusion of LTC4 (100 nm) in the patch pipette or after addition of agonist to the bath, a second DVF bath solution exchange was performed to determine LTC4-activated Na+ currents. The composition of DVF bath solution was 155 mm sodium methanesulfonate, 10 mm HEDTA, 1 mm EDTA, and 10 mm HEPES (pH 7.4 adjusted with NaOH). DVF solutions were used to amplify these otherwise tiny LRC currents. Current-voltage (I/V) curves corresponding to background currents were subtracted from I/V curves obtained after LTC4 dialysis through the patch pipette and maximal LRC current activation. The subtracted I/V curves are represented as independent I/V curves. Cells were maintained at a 0-mV holding potential during recordings. Reverse ramps were used (from + to −) lasting 250 ms each 2 s, high MgCl2 (8 mm) was included in the patch pipette to inhibit TRPM7 currents, and 3 μm nimodipine was added to the bath solution to stabilize membrane patches and reach better seals.

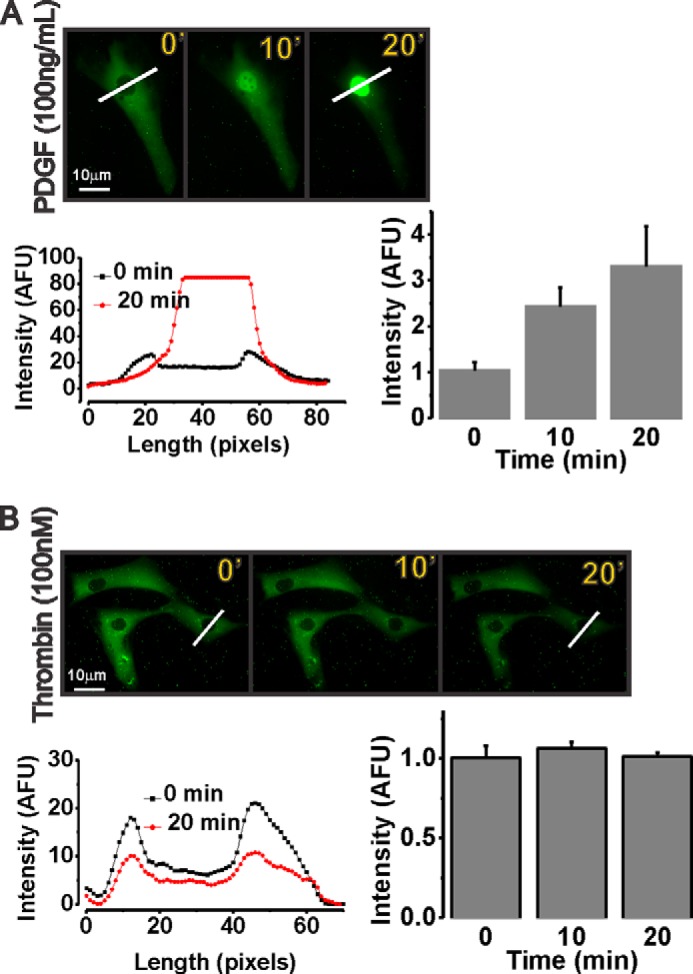

Nuclear Factor for Activated T Cells (NFAT)-GFP Nuclear Translocation Assays

Rat VSMCs were transfected with pEGFP plasmid encoding NFAT-GFP fusion protein (Addgene). Twenty-four hours after transfection cells were treated with 100 ng/ml platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) to activate store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE) channels (20) or 100 nm thrombin to activate LRC channels (13, 15). NFAT nuclear translocation was determined at 10 and 20 min after agonist additions by monitoring GFP fluorescence.

Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as means ± S.E., and statistical analysis was done using one-way analysis of variance with Origin software (OriginLab). Differences were considered significant when the p value was <0.05 and are indicated by asterisk(s). One, two, and three asterisks indicate p < 0.05, p < 0.01, and p < 0.001, respectively.

RESULTS

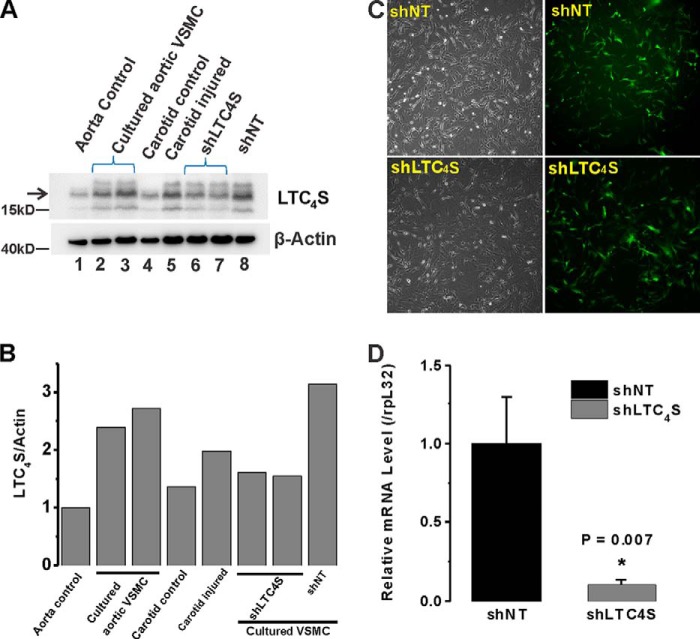

LTC4S Was Up-regulated in Synthetic VSMCs in Vitro and in Medial and Neointimal VSMCs after Vascular Injury in Vivo

LTC4S protein levels were up-regulated in cultured proliferative migratory aortic VSMCs (called synthetic VSMCs for being reminiscent of dedifferentiated VSMCs found in disease states) by comparison with acutely isolated quiescent VSMCs (Fig. 1A, compare lanes 2 and 3 with lane 1). Balloon injury of rat carotid artery is a well recognized in vivo model for neointima formation and vessel remodeling. Importantly, medial and neointimal VSMCs from balloon-injured carotid arteries at 2 weeks postinjury also showed enhanced LTC4S protein expression compared with VSMCs from non-injured carotid vessels (Fig. 1A, compare lane 5 with lane 4); please note that β-actin protein expression is also known to increase in dedifferentiated VSMCs (13, 24). LTC4S/β-actin ratios of band densitometry were determined using ImageJ software and are depicted in Fig. 1B. To knock down LTC4S protein expression, we generated two sets of lentiviral particles encoding either shLTC4S or control shNT. These lentiviral particles encoded the GFP under a separate promoter allowing for visualization of the efficiency of lentiviral infection. Cultured aortic VSMCs were infected with either shLTC4S or shNT lentiviruses for 24 h, and the infected cells were visualized at 48 h postinfection using GFP fluorescence. The infection efficiency was consistently higher than 90% (Fig. 1C). To document knockdown in vitro, proteins were collected from infected cultured aortic VSMCs at 7 days postinfection and processed for immunoblotting. LTC4S protein expression was inhibited in cultured aortic VSMCs (Fig. 1A, compare lanes 6 and 7 with lane 8). See Fig. 8C for statistical analysis of LTC4S/β-actin densitometry ratios from three independent experiments.

FIGURE 1.

A, LTC4S expression levels are higher in synthetic VSMCs (cultured proliferative aortic VSMCs; lane 2 and 3) compared with acutely isolated contractile/quiescent VSMCs (from medial aorta; lane 1). The LTC4S band is indicated by the arrow. Acutely isolated medial VSMCs from a healthy carotid artery (lane 4) and VSMCs from balloon-injured carotid artery (lane 5; 2 weeks postinjury) were assayed for LTC4S expression; LTC4S protein is up-regulated at 2 weeks after injury. Synthetic cultured aortic VSMCs infected with lentiviral particles encoding either shNT (lane 8) or shLTC4S (lanes 6 and 7) were lysed 7 days postinfection, and LTC4S expression was determined. B, densitometry of LTC4S and β-actin bands from experiment shown in A was performed using NIH ImageJ, and ratios of LTC4S/β-actin are represented. C, cultured synthetic VSMCs were infected with GFP-expressing lentiviral particles encoding either shLTC4S or shNT. Bright field images show total cells, and images of green fluorescence show successfully infected cells. The infection efficiency is >90%. D, VSMCs were infected by either shNT- or shLTC4S-encoding lentiviruses, and RT-PCR analysis was performed using LTC4S-specific primers and normalized to the 60 S ribosomal protein L32 (rpL32) transcript used as an internal control. Data represent the mean ± S.E. (error bars) from three independent infections. *, p < 0.05.

FIGURE 8.

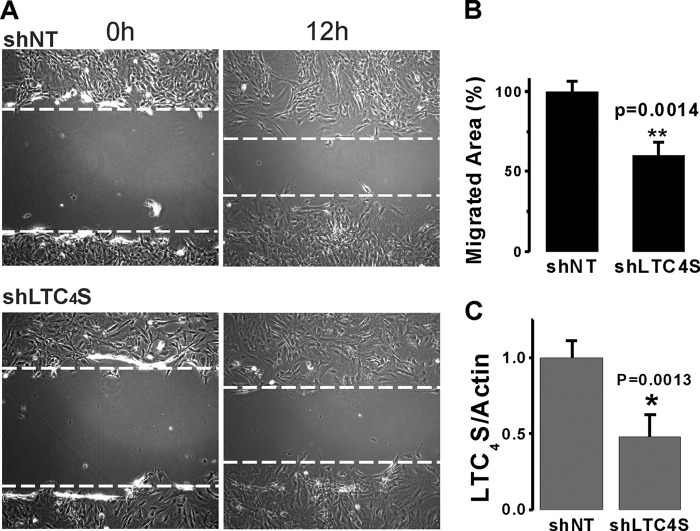

A and B, upon infection of cultured aortic VSMCs with lentivirus encoding either shNT or shLTC4S, scratch wound migration assays were performed in the presence of 10% FBS. The area of migrated cells at 12 h after scratch in control shNT-infected and shLTC4S-infected VSMCs (as seen in representative images in A) was determined and analyzed from three independent experiments (4 wells/condition) using NIH ImageJ software (B). C, statistical analysis on parallel Western blotting experiments documenting LTC4S protein knockdown in VSMCs used in migration assays from three independent experiments. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01. Error bars represent S.E.

The “housekeeping” genes classically used as loading controls, including β-actin, exhibit changes in protein and mRNA expression during the phenotypic modulation of smooth muscle from a contractile to a proliferative state (see e.g. Fig. 1A for β-actin protein). To ensure that LTC4S expression has indeed been inhibited by shRNA at the transcript level, we performed RT-PCR on VSMCs infected by either shNT or shLTC4S and documented significant LTC4S mRNA knockdown after shLTC4S infection (Fig. 1D); for these experiments, we used the 60 S ribosomal protein L32 gene transcript, which we empirically determined to be fairly stable between VSMC phenotypes (data not shown), as a control.

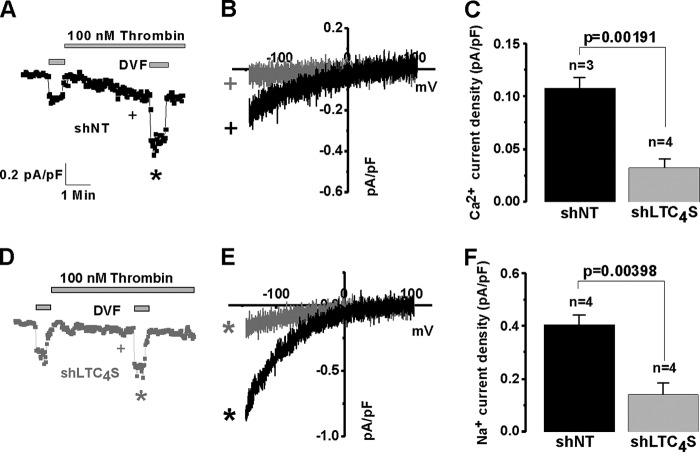

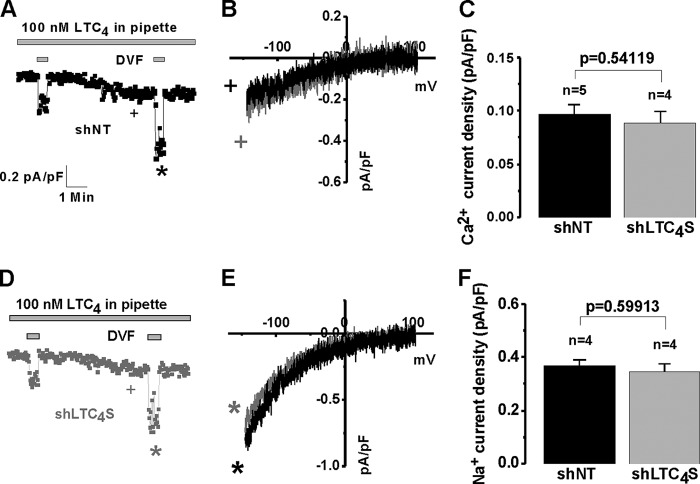

LTC4S Was Required for Receptor Activation of LRC Currents

We then used whole-cell patch clamp electrophysiology to document that LTC4S knockdown caused inhibition of LRC currents activated by thrombin, a VSMC agonist that we have previously shown to specifically activate LRC channels (13, 15) (Fig. 2, A and D). Fig. 2, B and E, show the typical I/V relationships of LRC currents in control shNT and shLTC4S conditions determined in Ca2+-containing extracellular bath solution (Fig. 2B) and upon amplification of LRC currents in DVF (Na+ ions are the charge carrier in this case) solutions (Fig. 2E). I/V curves were taken where indicated by the + and * symbols, and background subtractions are explained in detail under “Experimental Procedures.” Fig. 2, C and F, show statistical analysis of LRC Ca2+ (Fig. 2C) and Na+ (Fig. 2F) currents from several cells. However and as expected, LTC4S knockdown had no effect when LRC current was activated by direct dialysis of 100 nm LTC4 through the patch pipette into the cytosol of VSMCs (Fig. 3), suggesting that the LTC4S requirement was to produce LTC4, which was necessary for LRC channel activation. Fig. 3 has a similar layout to that of Fig. 2 in terms of current development, I/V relationships, and statistical analysis.

FIGURE 2.

Whole-cell patch clamp electrophysiological recordings were performed on rat synthetic aortic VSMCs that were infected with lentiviruses encoding either control shNT or shLTC4S. Silencing of LTC4S significantly inhibited thrombin-activated LRC currents (D) compared with control cells (A). LRC Ca2+ and Na+ I/V relationships for both conditions are shown in B and E, respectively. Statistics on LRC Ca2+ and Na+ current densities are shown in C and F, respectively. Ca2+ concentration in the pipette solution was buffered to 150 nm using the chelator 1,2-bis(2-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Error bars represent S.E. I/V curves were taken where indicated by the + and * symbols. pF, picofarad.

FIGURE 3.

Whole-cell patch clamp recordings were performed on synthetic VSMCs that were infected with lentiviruses encoding either control shNT or shLTC4S. Silencing of LTC4S did not affect LRC currents in VSMCs activated by direct dialysis with 100 nm LTC4 through the patch pipette (D; compare with shNT control in A). LRC Ca2+ and Na+ I/V relationships for both conditions are shown in B and E, respectively. Statistics on LRC Ca2+ and Na+ current densities are shown in C and F, respectively. Error bars represent S.E. I/V curves were taken where indicated by the + and * symbols. pF, picofarad.

Knockdown of LTC4S Inhibited Neointima Formation and Attenuated Vascular Remodeling in Vivo

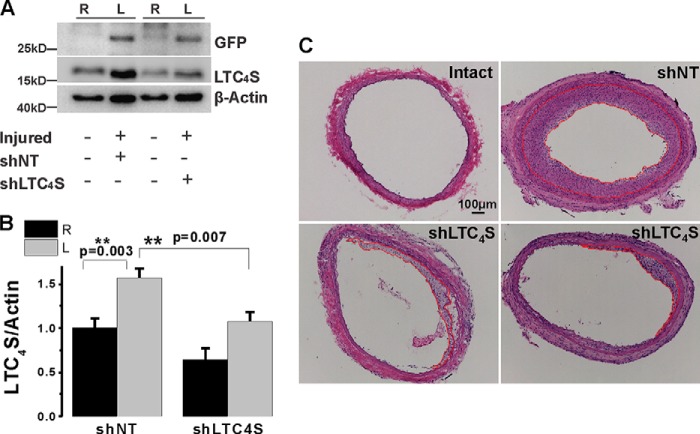

To document LTC4S knockdown in vivo, proteins were extracted from medial and neointimal VSMCs at 2 weeks after injury and lentiviral transduction. As reported in Fig. 1A, LTC4S protein expression was up-regulated in VSMCs from injured left carotids (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, in vivo transduction of injured vessels with lentivirus encoding specific shRNA against LTC4S attenuated LTC4S protein up-regulation in VSMCs from injured carotids, whereas lentivirus encoding shNT had no effect (Fig. 4A). LTC4S knockdown in carotid vessels in vivo was indeed due to successful infection by lentiviral particles encoding shRNA as left injured and infected vessels showed expression of GFP, which was absent from uninfected right carotid vessels (Fig. 4A). Expression of the β-actin protein was also increased as documented previously in this injury model (13, 24) (Fig. 4A). However, please note that β-actin protein levels were comparable when injured vessels (left) were compared with each other; the same holds true when control vessels (right) are compared with each other, providing further evidence that equivalent levels of total proteins are loaded into each well and that changes in β-actin protein expression are the result of vascular injury and VSMC dedifferentiation into a synthetic phenotype. Densitometry analysis using ImageJ software was used to quantify LTC4S protein levels in carotid VSMCs from six independent rats after vascular injury and viral transduction in vivo (Fig. 4B).

FIGURE 4.

A, acutely isolated VSMCs from control carotids (right carotids; R) and balloon-injured carotids (left carotids; L) transduced with lentiviral particles encoding either shNT or shLTC4S were harvested and lysed at 2 weeks postinjury, and LTC4S protein levels were determined. In the injured vessel treated with shLTC4S, the increase in LTC4S expression induced by balloon injury was significantly attenuated. As a control of in vivo infection with viruses, GFP expression was detected only in vessels transduced with lentiviruses (left carotid), indicating local and efficient infection with lentiviral particles. B, bar graph with statistical analysis of LTC4S protein expression from six independent in vivo experiments. No significant difference in intact carotids was observed between the two groups. Error bars represent S.E. C, images of rat carotid artery cross-sections from intact (control) vessels and from injured and shRNA-treated vessels harvested 2 weeks after injury. After injury, the vessel wall is significantly thicker, vessel size is bigger, and lumen is much smaller compared with the intact vessel, indicating both outward and inward remodeling of the artery in response to balloon injury. When treated with shLTC4S (the two lower panels show sections from two independent rats), neointimal hyperplasia was largely attenuated, and the lumen size was normalized by comparison with shNT-treated vessels. Scale bar, 100 μm. **, p < 0.01.

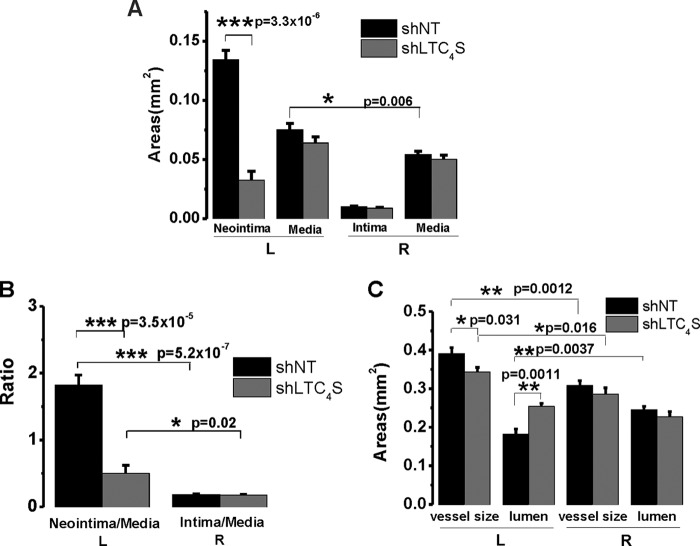

We showed previously that Orai3 knockdown inhibited neointima formation and attenuates vascular remodeling after balloon injury in rat carotids (13). To determine whether LTC4S in vivo knockdown also affects neointima formation, we used the same animal model of balloon angioplasty. After injury, rats were allowed to recover, then housed, and monitored for 2 weeks. At 2 weeks postinjury, rats were euthanized; the injured left carotid arteries and the intact right carotid arteries from the same animals were collected and subjected to cross-sectioning and H&E staining. Elastic laminas separating different layers of the vessel wall can be easily distinguished (Fig. 4C). In the control group in which the injured artery was treated with the control shNT virus, neointima formation was robust; please note the neointimal area delineated by a red line. However, when the artery was treated with shLTC4S virus after injury, neointima formation was significantly attenuated (Fig. 4C; two H&E sections from two different rats are shown in the bottom panels). The average neointima size in the shLTC4S group (n = 6) was only 24% of the size of the shNT group (Fig. 5A; n = 6; 0.032 versus 0.134; p = 3.3 × 10−6). The injury also induced a slight increase in media size. However, this increase was significant only in the control shNT group but not in the shLTC4S group (Fig. 5A). The ratio of neointima size to media size (neointima/media) in the shLTC4S-treated group was significantly less and was on average 27% of the ratio of the shNT control group (Fig. 5B; p = 3.5 × 10−5).

FIGURE 5.

A, statistical analysis of the cross-sectional areas (n = 6 rats per condition). Error bars represent S.E. In injured vessels, the average neointimal area of the shLTC4S group is significantly smaller than that of the shNT control group. The area size of the former is only one-fourth of the size of the latter (0.032 versus 0.134 mm2). The media size was slightly but significantly increased after injury compared with the intact artery (0.075 versus 0.064 mm2). When treated with shLTC4S, the injury-induced increase in media size was slightly attenuated, although this is not statistically significant. B, neointima size was normalized to media size to rule out variations in vessel size among different rats. For both groups, the neointima/media ratio is significantly higher compared with their respective right carotid controls. The neointima/media ratio of shLTC4S group is dramatically lower than that of the shNT group (0.50 versus 1.83). C, the left carotid vessel size was significantly enlarged after balloon injury compared with the intact right carotid artery from the same animal. For the shNT group, the injured artery size is 0.39 mm2, whereas the intact right control artery size is 0.31 mm2. For the shLTC4S group, the injured artery size is 0.34 mm2, whereas the intact right control artery size is 0.29 mm2. The intact artery sizes between these two groups were not significantly different, whereas the injured artery size of the shLTC4S group was significantly lower than that of the shNT group. The lumen was significantly narrowed after injury (0.18 versus 0.24 mm2). When treated with shLTC4S, the vessel lumen size was essentially normalized (0.25 versus 0.23 mm2). *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001.

The vessel size here represents the area within the external elastic lamina, which includes the media layer and intima/neointima layer. The outermost layer of the vessel wall, adventitia, is known to be thickened as well in response to balloon injury but was not included in the current analysis. This is because the adventitia is frequently involved in mild to moderate adhesion with surrounding tissues after injury that leads to difficulties in conclusively defining its edge (as seen in Fig. 4C). Statistical analysis showed that the vessel size significantly increased after injury regardless of the viral treatment. However, the size of the injured vessel in the shLTC4S group was significantly smaller than that of the shNT group (p = 0.031), indicating that the outward vascular remodeling has been inhibited by LTC4S in vivo knockdown (Fig. 5C). The lumen size was significantly reduced after injury and shNT transduction (p = 0.0037) but was similar to control when injured vessels were transduced with shLTC4S (p = 0.12). Thus, the inward remodeling that causes vessel narrowing and reduced blood supply was essentially abolished by LTC4S knockdown (Fig. 5C).

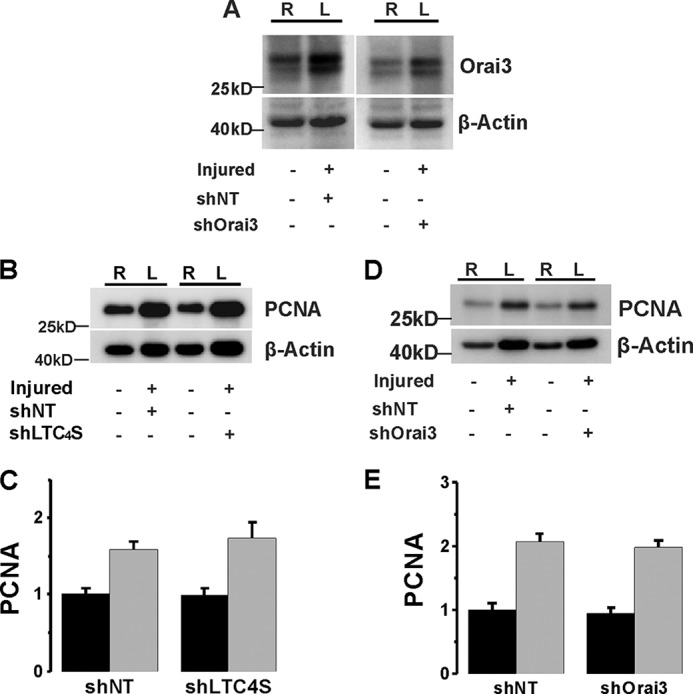

LTC4S and Orai3 in Vivo Knockdown Had No Effect on Expression of the Proliferative Marker PCNA

In the current study, we also used in parallel the same tissue samples from the same groups of mice used in our previous study in which injured carotid vessels were transduced with lentivirus encoding specific shRNA against Orai3 (13); in this previous study, Orai3 protein in vivo knockdown was documented. Nevertheless, Fig. 6A shows that Orai3 protein levels were increased after vascular injury and that shOrai3 was successful at reducing Orai3 protein expression (densitometry ratios of Orai3/β-actin are as follows: shNT, 0.86 ± 0.03; shOrai3, 0.46 ± 0.07; n = 6 independent rats).

FIGURE 6.

A, acutely isolated VSMCs from control carotids (right carotids; R) and balloon-injured carotids (left carotids; L) transduced with lentiviral particles encoding either shNT or shOrai3 were harvested and lysed at 2 weeks postinjury, and Orai3 protein levels were determined by Western blotting. In the injured vessel treated with shOrai3, the increase in Orai3 expression induced by balloon injury was significantly attenuated. B–E, PCNA expression in carotid artery was up-regulated after balloon injury. The expression level was not significantly changed upon either LTC4S (B and C) or Orai3 (D and E) in vivo knockdown. Statistical analysis on PCNA densitometry from six independent rats per group is shown for LTC4S (C) and Orai3 (E) in vivo knockdown. Error bars represent S.E.

Neointimal cells are mainly contributed by media-derived VSMCs through the processes of proliferation and migration. As expected, expression of the proliferative marker PCNA increased 2 weeks after carotid injury (Fig. 6, B–E). However, in stark contrast to the results obtained with both STIM1 and Orai1 knockdown in injured vessels in vivo (24), either LTC4S or Orai3 knockdown in injured carotids vessels failed to normalize the up-regulation of PCNA expression (Fig. 6, B–E).

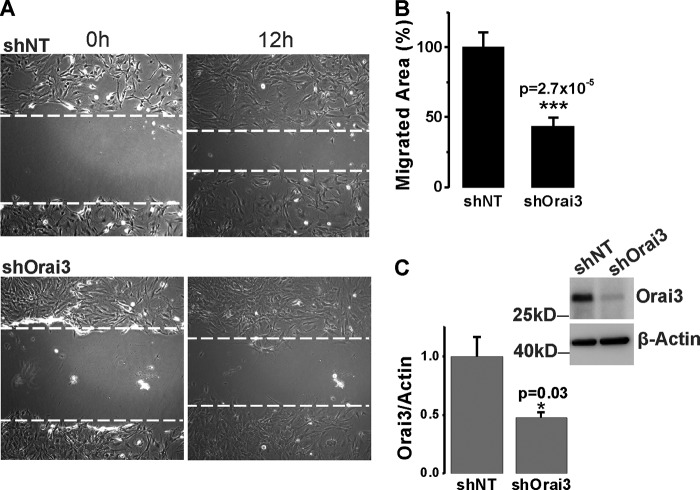

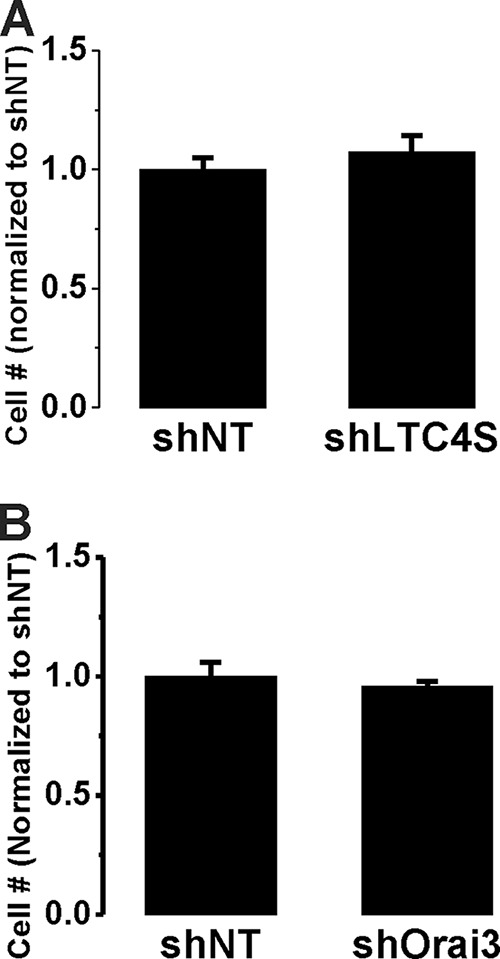

LTC4S and Orai3 Knockdown Inhibited Synthetic VSMC Migration but Not Proliferation in Vitro

The significant inhibitory effects of LTC4S and Orai3 in vivo knockdown on neointima formation contrasted with their failure to normalize the up-regulation of the proliferative marker PCNA. Therefore, we decided to use the in vitro culture system to determine whether LTC4S and Orai3 knockdown inhibits VSMC proliferation in response to serum stimulation. In contrast to VSMC in vitro proliferation assays with STIM1 and Orai1 knockdown (20, 23), knockdown of either LTC4S or Orai3 in cultured VSMCs using lentiviral shRNA infection failed to significantly affect cell proliferation at 7 days postinfection (Fig. 7), suggesting that the LTC4S/Orai3 pathway does not play a role in VSMC proliferation. Therefore, we reasoned that the effect of LTC4S/Orai3 knockdown on neointima formation in vivo might reflect an effect on medial VSMC migration as a prerequisite for neointima formation. We sought to determine the effect of LTC4S and Orai3 knockdown on VSMC migration using cultured VSMCs and the scratch wound assay. Knockdown of either LTC4S (Fig. 8C; see also Fig. 1A) or Orai3 (Fig. 9C shows a representative Western blot and statistical analysis from three independent experiments) in cultured aortic VSMCs significantly inhibited VSMC migration in response to serum. Figs. 8B and 9B represent data analyzed from a total of 12 wells originating from three independent infections, and Figs. 8C and 9C represent Western blot densitometry data analyzed from these three independent infections.

FIGURE 7.

Cultured aortic VSMCs were infected by shLTC4S (A) or shOrai3 (B) and shNT-infected VSMCs were used throughout as controls. After infection, VSMCs were counted, and equal numbers of cells were seeded in 6-well plates and counted 7 days postinfection. Data are the average ± S.E. (error bars) from 12 wells originating from three independent infections (4 wells/condition) and are normalized to shNT controls.

FIGURE 9.

A and B, scratch wound migration assay using cultured VSMCs in the presence of 10% FBS. Upon Orai3 knockdown by infection with lentivirus encoding shOrai3, the migrated area at 12 h after scratch in control shNT-infected and shOrai3-infected VSMCs (A) was determined and analyzed from three independent experiments (4 wells/condition) using NIH ImageJ software (B). C, representative anti-Orai3 Western blotting experiment documenting Orai3 protein knockdown in VSMCs and statistical analysis on three Western blotting experiments using cells assayed in migration assays. *, p < 0.05; ***, p < 0.001. Error bars represent S.E.

LTC4S and Orai3 Coupled to Akt Signaling but Not NFAT in Synthetic VSMCs

Earlier studies from our group and others have shown that PDGF, a potent VSMC proliferative agonist, activates Ca2+ entry through canonical SOCE channels mediated by STIM1 interaction with Orai1 upon depletion of intracellular stores (13, 20, 33). Furthermore, we and others have also shown that activation of SOCE in VSMCs led to NFAT nuclear translocation and enhanced NFAT transcriptional activity (18, 24, 33). Our results so far suggest that Orai3 and LTC4S, the two unique components of the LRC pathway, were required for VSMC migration but not proliferation. This is in contrast to STIM1 and Orai1, which were required for both LRC and SOCE channels and for both VSMC proliferation and migration (13, 15, 16, 20, 23, 24). This suggests that Ca2+ entry into VSMCs through LRC channels might couple to distinct or more restricted downstream signaling pathways than SOCE. Indeed, we show here that whereas PDGF causes NFAT nuclear translocation in VSMCs as would be expected (Fig. 10A) specific LRC channel activation by the agonist thrombin failed to cause NFAT nuclear translocation (Fig. 10B).

FIGURE 10.

PDGF (a SOCE channel activator) causes nuclear translocation of ectopically expressed NFAT-GFP at 10 and 20 min poststimulation (A), whereas thrombin (an LRC channel activator) fails to cause NFAT-GFP translocation (B). Blots representing cell cross-sections of fluorescence intensity (diagonal white bars) at 0 and 20 min and quantification of data at 0-, 10-, and 20-min (′) time points from four independent experiments per condition are shown. Scale bars, 10 μm. Error bars represent S.E. AFU, arbitrary fluorescence units.

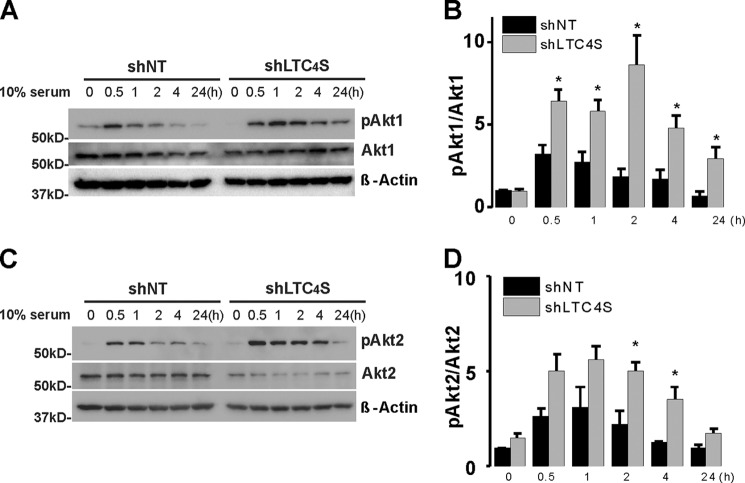

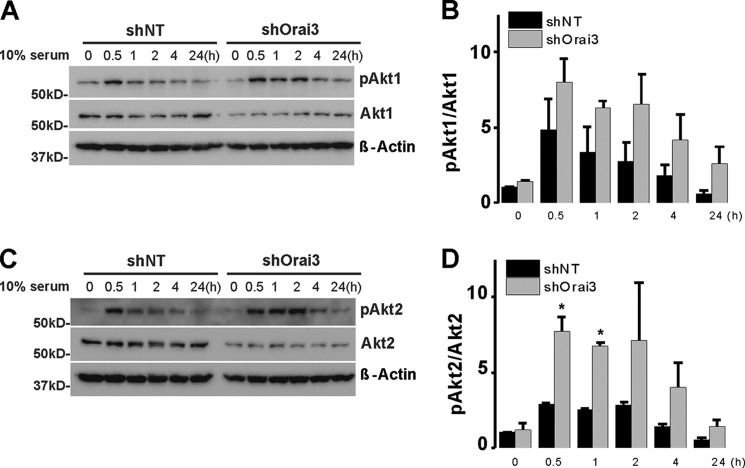

This observation prompted us to screen for potential downstream effectors whose activation is equally affected by knockdown of LTC4S and Orai3, the two unique components of the LRC pathway. LTC4S and Orai3 knockdown failed to affect protein expression or phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and focal adhesion kinase/paxillin (not shown). Quite surprisingly, LTC4S and Orai3 knockdown led to increased and more sustained (up to 24 h) Akt1 and Akt2 activatory phosphorylation on Ser-473 and Ser-474, respectively, in response to serum stimulation without affecting either Akt1 or Akt2 protein levels (Figs. 11 and 12). Figs. 11 and 12 show an apparent decrease in total Akt2 protein levels upon LTC4S and Orai3 knockdown. However, this decrease was not statistically significant.

FIGURE 11.

Rat cultured aortic VSMCs were treated with lentivirus encoding shLTC4S or control shNT. After LTC4S knockdown, VSMCs were cultured in DMEM/F-12 with 0.4% serum for 24 h prior to treatment with medium containing 10% serum over the time course indicated (30 min to 24 h). VSMCs without serum treatment (time 0 controls) and at different times after serum treatment were lysed or processed for Western blotting using Akt1 (A) and Akt2 (C) isoform-specific antibodies probing phospho-Ser-473 Akt1, total Akt1, phospho-Ser-474 Akt2, Akt2, and β-actin (loading control). B and D represent phospho-Akt (pAkt)/Akt Western blot densitometry performed on VSMCs from three independent shRNA infections. The asterisks indicate statistical significance between the shLTC4S and shNT conditions at the same time point. *, p < 0.05. Error bars represent S.E.

FIGURE 12.

Cultured aortic VSMCs were treated with lentivirus encoding shOrai3 or control shNT. After Orai3 knockdown, VSMCs were cultured in DMEM/F-12 with 0.4% serum for 24 h prior to treatment with medium containing 10% serum over the time course indicated (30 min to 24 h). VSMCs without serum treatment (time 0 controls) and at different times after serum treatment were lysed or processed for Western blotting using Akt1 (A) and Akt2 (C) isoform-specific antibodies probing phospho-Ser-473 Akt1, total Akt1, phospho-Ser-474 Akt2, Akt2, and β-actin (loading control). B and D represent phospho-Akt (pAkt)/Akt Western blot densitometry performed on VSMCs from three independent shRNA infections. The asterisks indicate statistical significance between the shOrai3 and shNT conditions at the same time point. *, p < 0.05. Error bars represent S.E.

LTC4S and Orai3 in Vivo Knockdown in Injured Vessels Restored Akt Phosphorylation in VSMCs

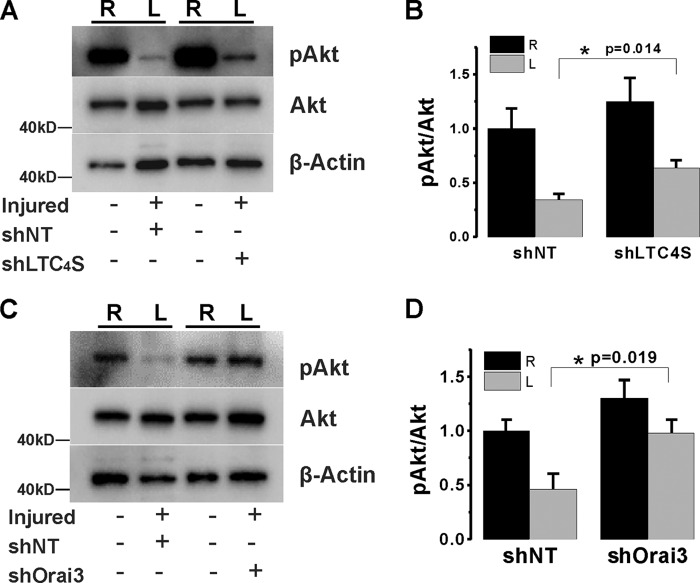

In light of the in vitro results described above, we sought to confirm this observation in vivo by determining whether Akt phosphorylation is also affected by LTC4S and Orai3 in vivo knockdown in injured vessels. Our in vivo experiments showed that Akt displays constitutive phosphorylation on Ser-474/473 in intact control vessels. In injured vessel, we consistently found that the basal levels of phosphorylated Akt at 2 weeks postinjury are significantly lower than those of control vessels (Fig. 13, A and B). Significantly, upon LTC4S knockdown in injured artery, Akt phosphorylation was partially restored. Similarly, Orai3 knockdown in injured vessels normalized phospho-Akt levels (Fig. 13, C and D).

FIGURE 13.

Western blotting data on VSMCs acutely isolated from injured (left; L) and control (right; R) carotid vessels at 2 weeks after balloon injury and lentiviral transduction with control shNT and shLTC4S (A) or shOrai3 (B). The levels of Akt phosphorylation on serine 473 (pAkt) and total Akt were determined using Western blotting and specific antibodies (recognizing all three isoforms of Akt; see “Experimental Procedures”). The phospho-Akt levels largely decreased at 2 weeks postinjury, whereas total Akt levels did not change compared with control. When the injured carotid arteries were treated with either shLTC4S or shOrai3, the injury-induced decrease of phospho-Akt levels was partially restored. B and D show statistical analysis on phospho-Akt/Akt Western blot densitometry performed on VSMCs isolated from six rats per group. *, p < 0.05. Error bars represent S.E.

DISCUSSION

LTC4S plays an important role in the inflammatory immune response associated with a large number of diseases. For instance, it was shown that in human abdominal aortic aneurysms CysLTs, but not LTB4, are the major metabolites produced from arachidonic acid metabolism through the 5-lipooxygenase pathway and that protein levels of LTCS, 5-lipoxygenase, and 5-lipoxygenase-activating protein are significantly increased (34). The crystal structure of LTC4S has been recently resolved and revealed a homotrimeric organization (35). Very recent studies suggest that LTC4S could represent a promising drug target for disease therapy as its activity can be specifically modulated by potent small inhibitors (36, 37). Because CysLTs are primarily produced by leukocytes and were originally found to mediate inflammation and smooth muscle contraction, their roles in mediating cardiovascular diseases have been implicitly assumed to occur through their action on their specific G protein-coupled receptors, especially CysLT receptors expressed on the surface of VSMCs, endothelial cells, and macrophages (38). As such, the role of CysLTs originating from cells of the vessel wall (i.e. endothelial cells and VSMCs) and acting as intracellular second messenger molecules in vascular diseases is not documented. Our studies describe a novel paradigm whereby intracellular LTC4 activates a novel store-independent Ca2+ signaling route in VSMCs through heteromultimeric Orai1/3 channels (13–17) that impact Akt activation, VSMC migration, and neointima formation.

Akt is a kinase that is activated by phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase (PI3K)-mediated phosphorylation on serine 473 (39). Akt was a major cell signaling molecule important for inhibition of VSMC migration and maintenance of VSMC quiescence (40). Several studies support a protective role for Akt in the vasculature as compromised Akt activation led to a range of vascular disorders, including insulin resistance (41, 42), aortic aneurysms (43), Marfan syndrome (44), and hypertension (45). The Akt/PI3K pathway was activated by insulin and contributed to the protective vascular effects of insulin; impaired PI3K signaling during insulin resistance was associated with enhanced VSMC migration and failure of insulin to maintain VSMC quiescence (41, 42). In a model of stent-induced injury in insulin-resistant and diabetic rats, injured vessels showed a reduction in phospho-Akt in agreement with our findings. Akt activation has been found to be up-regulated in the injured artery at the initial stage within 3 days after balloon injury (46, 47). This increased Akt activation likely contributed to VSMC survival that counteracts the extensive apoptosis occurring right after mechanical injury (48, 49). However, at later stages of neointimal hyperplasia (1–2 weeks postinjury), Akt activity was decreased (46, 47).

Our results showed that LTC4S and Orai3 knockdown had no effect on VSMC proliferation but significantly inhibited neointima formation in vivo. The simplest explanation for these observations is a role for up-regulated LTC4S and Orai3 in promoting VSMC phenotypic switch or dedifferentiation. This idea is also consistent with the inhibitory effects of LTC4S and Orai3 knockdown on VSMC migration in vitro. Our findings are consistent with studies describing an essential role of Akt1 and Akt2 isoforms in promoting VSMC differentiation and inhibiting VSMC migration. Indeed, Akt2 was required for rapamycin-induced VSMC differentiation (40), and Akt2 knock-out mice exhibited exacerbated neointimal hyperplasia that was insensitive to inhibition by rapamycin.5 Furthermore, it was shown that the downstream target of Akt2 at the transcriptional level is GATA-6, which drives the expression of VSMC differentiation genes.6 A recent study showed that neointima formation in carotid artery ligation and high fat diet-induced atherosclerosis was facilitated in mice lacking Akt1 (50). Moreover, down-regulation of the Akt1 isoform in epithelial cells promoted enhanced cell migration and substantial neomorphic effects typical of the epithelial to mesenchymal transition (51).

A couple of questions remain: what caused suppression of Akt activation at later stages of vascular injury, and how did LTC4S/Orai3-mediated Ca2+ signals impinge on the Akt pathway? Regarding the first question, Akt activity is subjected to complex regulation, including self-regulation through negative feedback. A new critical player in the Akt signaling network is the pleckstrin homology domain leucine-rich repeat protein phosphatase (PHLPP), which inhibited Akt through its dephosphorylation on the critical site Ser-473. Interestingly, PHLPP activity is enhanced by activated Akt through at least two mechanisms. 1) Activated Akt promotes the activation of mTORC1, which enhances PHLPP expression via the ribosomal protein S6 kinase (52). 2) Activated Akt inhibited glycogen synthase kinase-3 activity and thus prevented glycogen synthase kinase-3-dependent PHLPP degradation (53, 54). As for the second question, it is quite possible that the LTC4S/Orai3-mediated Ca2+ entry pathway described in our studies was involved in this negative feedback of Akt activation. Clearly, extensive and detailed studies on the various molecular players listed above are needed to firmly determine the precise mechanisms of LTC4S/Orai3-mediated Akt regulation. In conclusion, we found that VSMC-derived LTC4S played an essential role in neointima formation and vascular remodeling. Therefore, LTC4S represents a potential target for treatment of vascular occlusive diseases.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants R01HL097111 and R01HL123364 (to M. T.) and R01HL095566 (to K. M.). This work was also supported by American Heart Association Grant 14GRNT18880008 (to M. T.).

Y. Jin, poster presented at the North American Vascular Biology Organization Meeting, New Haven, Connecticut (May 8–10, 2014).

Y. Xie, poster presented at the North American Vascular Biology Organization Meeting, New Haven, Connecticut (May 8–10, 2014).

- VSMC

- vascular smooth muscle cell

- LT

- leukotriene

- LTC4S

- leukotriene-C4 synthase

- LRC

- LTC4-regulated Ca2+

- CysLT

- cysteinyl leukotriene

- shLTC4S

- shRNA against LTC4S

- shOrai3

- shRNA against Orai3

- shNT

- non-targeting shRNA

- DVF

- divalent-free

- HEDTA

- N-(2-hydroxyethyl)ethylenediaminetriacetic acid

- I/V

- current-voltage

- SOCE

- store-operated Ca2+ entry

- PCNA

- proliferating cell nuclear antigen

- PHLPP

- pleckstrin homology domain leucine-rich repeat protein phosphatase.

REFERENCES

- 1. House S. J., Potier M., Bisaillon J., Singer H. A., Trebak M. (2008) The non-excitable smooth muscle: calcium signaling and phenotypic switching during vascular disease. Pflugers Arch. 456, 769–785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Austen K. F. (2008) The cysteinyl leukotrienes: where do they come from? What are they? Where are they going? Nat. Immunol. 9, 113–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Peters-Golden M., Henderson W. R., Jr. (2007) Leukotrienes. New Engl. J. Med. 357, 1841–1854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Taccone-Gallucci M., Manca-di-Villahermosa S., Maccarrone M. (2008) Leukotrienes. New Engl. J. Med. 358, 746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cowburn A. S., Sladek K., Soja J., Adamek L., Nizankowska E., Szczeklik A., Lam B. K., Penrose J. F., Austen F. K., Holgate S. T., Sampson A. P. (1998) Overexpression of leukotriene C4 synthase in bronchial biopsies from patients with aspirin-intolerant asthma. J. Clin. Investig. 101, 834–846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sanak M., Simon H. U., Szczeklik A. (1997) Leukotriene C4 synthase promoter polymorphism and risk of aspirin-induced asthma. Lancet 350, 1599–1600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bevan S., Dichgans M., Wiechmann H. E., Gschwendtner A., Meitinger T., Markus H. S. (2008) Genetic variation in members of the leukotriene biosynthesis pathway confer an increased risk of ischemic stroke: a replication study in two independent populations. Stroke 39, 1109–1114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Freiberg J. J., Dahl M., Tybjaerg-Hansen A., Grande P., Nordestgaard B. G. (2009) Leukotriene C4 synthase and ischemic cardiovascular disease and obstructive pulmonary disease in 13,000 individuals. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 46, 579–586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Freiberg J. J., Tybjaerg-Hansen A., Sillesen H., Jensen G. B., Nordestgaard B. G. (2008) Promotor polymorphisms in leukotriene C4 synthase and risk of ischemic cerebrovascular disease. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 28, 990–996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Iovannisci D. M., Lammer E. J., Steiner L., Cheng S., Mahoney L. T., Davis P. H., Lauer R. M., Burns T. L. (2007) Association between a leukotriene C4 synthase gene promoter polymorphism and coronary artery calcium in young women: the Muscatine Study. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 27, 394–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Berna-Erro A., Galan C., Dionisio N., Gomez L. J., Salido G. M., Rosado J. A. (2012) Capacitative and non-capacitative signaling complexes in human platelets. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1823, 1242–1251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Thompson J. L., Shuttleworth T. J. (2013) Exploring the unique features of the ARC channel, a store-independent Orai channel. Channels 7, 364–373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. González-Cobos J. C., Zhang X., Zhang W., Ruhle B., Motiani R. K., Schindl R., Muik M., Spinelli A. M., Bisaillon J. M., Shinde A. V., Fahrner M., Singer H. A., Matrougui K., Barroso M., Romanin C., Trebak M. (2013) Store-independent Orai1/3 channels activated by intracrine leukotriene C4: role in neointimal hyperplasia. Circ. Res. 112, 1013–1025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ruhle B., Trebak M. (2013) Emerging roles for native Orai Ca2+ channels in cardiovascular disease. Curr. Top. Membr. 71, 209–235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhang X., González-Cobos J. C., Schindl R., Muik M., Ruhle B., Motiani R. K., Bisaillon J. M., Zhang W., Fahrner M., Barroso M., Matrougui K., Romanin C., Trebak M. (2013) Mechanisms of STIM1 activation of store-independent leukotriene C4-regulated Ca2+ channels. Mol. Cell. Biol. 33, 3715–3723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhang X., Zhang W., González-Cobos J. C., Jardin I., Romanin C., Matrougui K., Trebak M. (2014) Complex role of STIM1 in the activation of store-independent Orai1/3 channels. J. Gen. Physiol. 143, 345–359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Motiani R. K., Stolwijk J. A., Newton R. L., Zhang X., Trebak M. (2013) Emerging roles of Orai3 in pathophysiology. Channels 7, 392–401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Aubart F. C., Sassi Y., Coulombe A., Mougenot N., Vrignaud C., Leprince P., Lechat P., Lompré A. M., Hulot J. S. (2009) RNA interference targeting STIM1 suppresses vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and neointima formation in the rat. Mol. Ther. 17, 455–462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Berra-Romani R., Mazzocco-Spezzia A., Pulina M. V., Golovina V. A. (2008) Ca2+ handling is altered when arterial myocytes progress from a contractile to a proliferative phenotype in culture. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 295, C779–C790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bisaillon J. M., Motiani R. K., Gonzalez-Cobos J. C., Potier M., Halligan K. E., Alzawahra W. F., Barroso M., Singer H. A., Jourd'heuil D., Trebak M. (2010) Essential role for STIM1/Orai1-mediated calcium influx in PDGF-induced smooth muscle migration. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 298, C993–C1005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Guo R. W., Wang H., Gao P., Li M. Q., Zeng C. Y., Yu Y., Chen J. F., Song M. B., Shi Y. K., Huang L. (2009) An essential role for stromal interaction molecule 1 in neointima formation following arterial injury. Cardiovasc. Res. 81, 660–668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Guo R. W., Yang L. X., Li M. Q., Pan X. H., Liu B., Deng Y. L. (2012) Stim1- and Orai1-mediated store-operated calcium entry is critical for angiotensin II-induced vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation. Cardiovasc. Res. 93, 360–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Potier M., Gonzalez J. C., Motiani R. K., Abdullaev I. F., Bisaillon J. M., Singer H. A., Trebak M. (2009) Evidence for STIM1- and Orai1-dependent store-operated calcium influx through ICRAC in vascular smooth muscle cells: role in proliferation and migration. FASEB J. 23, 2425–2437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zhang W., Halligan K. E., Zhang X., Bisaillon J. M., Gonzalez-Cobos J. C., Motiani R. K., Hu G., Vincent P. A., Zhou J., Barroso M., Singer H. A., Matrougui K., Trebak M. (2011) Orai1-mediated I (CRAC) is essential for neointima formation after vascular injury. Circ. Res. 109, 534–542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zhang W., Trebak M. (2012) in TRP Channels in Drug Discovery (Szallasi A., Bíró T., eds) pp. 101–111, Humana Press, Totowa, NJ [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhang W., Trebak M. (2014) Vascular balloon injury and intraluminal administration in rat carotid artery. J. Vis. Exp. 10.3791/52045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Motiani R. K., Hyzinski-García M. C., Zhang X., Henkel M. M., Abdullaev I. F., Kuo Y. H., Matrougui K., Mongin A. A., Trebak M. (2013) STIM1 and Orai1 mediate CRAC channel activity and are essential for human glioblastoma invasion. Pflugers Arch. 465, 1249–1260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Shinde A. V., Motiani R. K., Zhang X., Abdullaev I. F., Adam A. P., González-Cobos J. C., Zhang W., Matrougui K., Vincent P. A., Trebak M. (2013) STIM1 controls endothelial barrier function independently of Orai1 and Ca2+ entry. Sci. Signal. 6, ra18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Spinelli A. M., González-Cobos J. C., Zhang X., Motiani R. K., Rowan S., Zhang W., Garrett J., Vincent P. A., Matrougui K., Singer H. A., Trebak M. (2012) Airway smooth muscle STIM1 and Orai1 are upregulated in asthmatic mice and mediate PDGF-activated SOCE, CRAC currents, proliferation, and migration. Pflugers Arch. 464, 481–492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Motiani R. K., Zhang X., Harmon K. E., Keller R. S., Matrougui K., Bennett J. A., Trebak M. (2013) Orai3 is an estrogen receptor alpha-regulated Ca2+ channel that promotes tumorigenesis. FASEB J. 27, 63–75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Motiani R. K., Abdullaev I. F., Trebak M. (2010) A novel native store-operated calcium channel encoded by Orai3: selective requirement of Orai3 versus Orai1 in estrogen receptor-positive versus estrogen receptor-negative breast cancer cells. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 19173–19183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Abdullaev I. F., Bisaillon J. M., Potier M., Gonzalez J. C., Motiani R. K., Trebak M. (2008) Stim1 and Orai1 mediate CRAC currents and store-operated calcium entry important for endothelial cell proliferation. Circ. Res. 103, 1289–1299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mancarella S., Potireddy S., Wang Y., Gao H., Gandhirajan R. K., Autieri M., Scalia R., Cheng Z., Wang H., Madesh M., Houser S. R., Gill D. L. (2013) Targeted STIM deletion impairs calcium homeostasis, NFAT activation, and growth of smooth muscle. FASEB J. 27, 893–906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Di Gennaro A., Wågsäter D., Mäyränpää M. I., Gabrielsen A., Swedenborg J., Hamsten A., Samuelsson B., Eriksson P., Haeggström J. Z. (2010) Increased expression of leukotriene C4 synthase and predominant formation of cysteinyl-leukotrienes in human abdominal aortic aneurysm. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 21093–21097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Martinez Molina D., Wetterholm A., Kohl A., McCarthy A. A., Niegowski D., Ohlson E., Hammarberg T., Eshaghi S., Haeggström J. Z., Nordlund P. (2007) Structural basis for synthesis of inflammatory mediators by human leukotriene C4 synthase. Nature 448, 613–616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ago H., Okimoto N., Kanaoka Y., Morimoto G., Ukita Y., Saino H., Taiji M., Miyano M. (2013) A leukotriene C4 synthase inhibitor with the backbone of 5-(5-methylene-4-oxo-4,5-dihydrothiazol-2-ylamino)isophthalic acid. J. Biochem. 153, 421–429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Niegowski D., Kleinschmidt T., Olsson U., Ahmad S., Rinaldo-Matthis A., Haeggström J. Z. (2014) Crystal structures of leukotriene C4 synthase in complex with product analogs: implications for the enzyme mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 5199–5207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Osher E., Weisinger G., Limor R., Tordjman K., Stern N. (2006) The 5 lipoxygenase system in the vasculature: emerging role in health and disease. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 252, 201–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hers I., Vincent E. E., Tavaré J. M. (2011) Akt signalling in health and disease. Cell. Signal. 23, 1515–1527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Martin K. A., Merenick B. L., Ding M., Fetalvero K. M., Rzucidlo E. M., Kozul C. D., Brown D. J., Chiu H. Y., Shyu M., Drapeau B. L., Wagner R. J., Powell R. J. (2007) Rapamycin promotes vascular smooth muscle cell differentiation through insulin receptor substrate-1/phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt2 feedback signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 36112–36120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Jonas M., Edelman E. R., Groothuis A., Baker A. B., Seifert P., Rogers C. (2005) Vascular neointimal formation and signaling pathway activation in response to stent injury in insulin-resistant and diabetic animals. Circ. Res. 97, 725–733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wang C. C., Gurevich I., Draznin B. (2003) Insulin affects vascular smooth muscle cell phenotype and migration via distinct signaling pathways. Diabetes 52, 2562–2569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Shen Y. H., Zhang L., Ren P., Nguyen M. T., Zou S., Wu D., Wang X. L., Coselli J. S., LeMaire S. A. (2013) AKT2 confers protection against aortic aneurysms and dissections. Circ. Res. 112, 618–632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Chung A. W., Au Yeung K., Cortes S. F., Sandor G. G., Judge D. P., Dietz H. C., van Breemen C. (2007) Endothelial dysfunction and compromised eNOS/Akt signaling in the thoracic aorta during the progression of Marfan syndrome. Br. J. Pharmacol. 150, 1075–1083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sampaio W. O., Souza dos Santos R. A., Faria-Silva R., da Mata Machado L. T., Schiffrin E. L., Touyz R. M. (2007) Angiotensin-(1–7) through receptor Mas mediates endothelial nitric oxide synthase activation via Akt-dependent pathways. Hypertension 49, 185–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Shigematsu K., Koyama H., Olson N. E., Cho A., Reidy M. A. (2000) Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling is important for smooth muscle cell replication after arterial injury. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 20, 2373–2378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Yang H. M., Kim H. S., Park K. W., You H. J., Jeon S. I., Youn S. W., Kim S. H., Oh B. H., Lee M. M., Park Y. B., Walsh K. (2004) Celecoxib, a cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor, reduces neointimal hyperplasia through inhibition of Akt signaling. Circulation 110, 301–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Malik N., Francis S. E., Holt C. M., Gunn J., Thomas G. L., Shepherd L., Chamberlain J., Newman C. M., Cumberland D. C., Crossman D. C. (1998) Apoptosis and cell proliferation after porcine coronary angioplasty. Circulation 98, 1657–1665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Stabile E., Zhou Y. F., Saji M., Castagna M., Shou M., Kinnaird T. D., Baffour R., Ringel M. D., Epstein S. E., Fuchs S. (2003) Akt controls vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation in vitro and in vivo by delaying G1/S exit. Circ. Res. 93, 1059–1065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Yun S. J., Ha J. M., Kim E. K., Kim Y. W., Jin S. Y., Lee D. H., Song S. H., Kim C. D., Shin H. K., Bae S. S. (2014) Akt1 isoform modulates phenotypic conversion of vascular smooth muscle cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1842, 2184–2192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Irie H. Y., Pearline R. V., Grueneberg D., Hsia M., Ravichandran P., Kothari N., Natesan S., Brugge J. S. (2005) Distinct roles of Akt1 and Akt2 in regulating cell migration and epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J. Cell Biol. 171, 1023–1034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Liu J., Stevens P. D., Gao T. (2011) mTOR-dependent regulation of PHLPP expression controls the rapamycin sensitivity in cancer cells. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 6510–6520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Warfel N. A., Niederst M., Stevens M. W., Brennan P. M., Frame M. C., Newton A. C. (2011) Mislocalization of the E3 ligase, β-transducin repeat-containing protein 1 (β-TrCP1), in glioblastoma uncouples negative feedback between the pleckstrin homology domain leucine-rich repeat protein phosphatase 1 (PHLPP1) and Akt. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 19777–19788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Warfel N. A., Newton A. C. (2012) Pleckstrin homology domain leucine-rich repeat protein phosphatase (PHLPP): a new player in cell signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 3610–3616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]