Background: Heparan sulfate colocalizes with amyloid-β in senile plaques of Alzheimer disease.

Results: Overexpression of the heparan sulfate-degrading enzyme (heparanase) lowers the amyloid burden in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer disease.

Conclusion: Heparan sulfate modulates amyloid-β deposition.

Significance: We present the first direct in vivo proof that heparan sulfate actively participates in senile plaque formation.

Keywords: Alzheimer Disease, Amyloid, Amyloid-β (AB), Glycosaminoglycan, Heparan Sulfate, Heparanase, Neuroscience, Proteoglycan, Transgenic Mice

Abstract

Heparan sulfate (HS) and HS proteoglycans (HSPGs) colocalize with amyloid-β (Aβ) deposits in Alzheimer disease brain and in Aβ precursor protein (AβPP) transgenic mouse models. Heparanase is an endoglycosidase that specifically degrades the unbranched glycosaminoglycan side chains of HSPGs. The aim of this study was to test the hypothesis that HS and HSPGs are active participators of Aβ pathogenesis in vivo. We therefore generated a double-transgenic mouse model overexpressing both human heparanase and human AβPP harboring the Swedish mutation (tgHpa*Swe). Overexpression of heparanase did not affect AβPP processing because the steady-state levels of Aβ1–40, Aβ1–42, and soluble AβPP β were the same in 2- to 3-month-old double-transgenic tgHpa*Swe and single-transgenic tgSwe mice. In contrast, the Congo red-positive amyloid burden was significantly lower in 15-month-old tgHpa*Swe brain than in tgSwe brain. Likewise, the Aβ burden, measured by Aβx-40 and Aβx-42 immunohistochemistry, was reduced significantly in tgHpa*Swe brain. The intensity of HS-stained plaques correlated with the Aβx-42 burden and was reduced in tgHpa*Swe mice. Moreover, the HS-like molecule heparin facilitated Aβ1–42-aggregation in an in vitro Thioflavin T assay. The findings suggest that HSPGs contribute to amyloid deposition in tgSwe mice by increasing Aβ fibril formation because heparanase-induced fragmentation of HS led to a reduced amyloid burden. Therefore, drugs interfering with Aβ-HSPG interactions might be a potential strategy for Alzheimer disease treatment.

Introduction

Alzheimer disease (AD),5 the most common dementia disorder, is characterized clinically by progressive memory and planning deficits together with reduced spatial orientation and logical thinking as well as behavioral changes. Neuropathologically, there are macroscopic atrophy and microscopic lesions like neurofibrillary tangles, amyloid-β (Aβ) immunoreactive senile plaques, and cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA). Aβ deposits of AD also contain accessory molecules such as heparan sulfate (HS), serum amyloid-P component, apolipoprotein E, and α1-antichymotrypsin. However, the functional role of HS in AD pathogenesis is not yet fully resolved (1, 2). HS and HS proteoglycans (HSPGs) colocalize particularly with mature Aβ deposits in the AD brain and animal models thereof (3–7). The conformation and fibrillar state of Aβ influences its molecular interaction with the HS-like molecule heparin (8), a highly sulfated glycosaminoglycan that is commonly used in vitro as a model for HS. HS/HSPGs and heparin have been found to alter amyloid-β precursor protein (AβPP) processing (9–11) and to increase Aβ aggregation (12, 13). Although substantial evidence points to an important role of HS in Aβ deposition in the brain, the majority of the available information has been obtained by invasive in vivo experiments (14, 15) or in vitro studies (10–12). The potential, specific role and effect of HS on Aβ deposition in the brain under native conditions remain to be fully established.

Proteoglycans consist of a core protein with covalently attached glycosaminoglycan side chains (e.g. HS and chondroitin sulfate). HSPGs are ubiquitously expressed in mammalian cells and localized mainly in the extracellular matrix (perlecan, type XVIII collagen, and agrin) and plasma membrane (syndecans and glypicans). The HS side chains of HSPGs are linear polysaccharides with alternating N-acetylated or N-sulfated glucosamines and hexauronic acids (16). Alternating side chain lengths and sulfation patterns generate an immense structural variability among HSPGs, even within the same subtype (17). Because of their negative charge (18), HS side chains can immobilize various ligands (e.g. growth factors), change their conformation, present them to a signaling receptor, or modify the interaction with their specific receptors. Therefore, receptor activation can be enhanced even at low ligand concentrations by, for example, increasing the local ligand concentration near the receptor (19–21).

It has been found previously that augmentation of Aβ aggregation critically depended on the sulfate moieties in the glycosaminoglycan chains of proteoglycans. Because inorganic sulfate ions did not affect Aβ aggregation, it was concluded that the linear organization of the sulfated glycosaminoglycans were of essence particularly for binding to early Aβ fibrils (12). We have proposed that a minimum length of the sulfated HS side chains is a prerequisite for Aβ fibril formation in vivo (22).

HSPGs can be modified by proteolytic cleavage of the core protein and fragmentation of the HS side chains by the endo-β-d-glucuronidase heparanase. The continuous modifications of HSPGs likely provide a mechanism by which cells are able to rapidly respond to a changing extracellular environment (23). By altering HSPGs on the cell surface (24), heparanase presumably regulates the cellular response to external stimuli. We have shown previously that heparanase-overexpressing mice were resistant to experimentally induced serum amyloid A amyloidosis because of shortening of the HS side chains by heparanase (22).

Our recent study showed that overexpression of heparanase delayed clearance of Aβ fibrils when these were injected into the brain (15). In this work, we asked whether in vivo overexpression of heparanase affects de novo deposition of Aβ. To investigate this non-invasively, we crossed heparanase-overexpressing mice (denoted tgHpa in this work) with transgenic mice overexpressing human AβPP harboring only the Swedish mutation (tgSwe) (25, 26). We examined Aβ deposition in the brains of these double-transgenic tgHpa*Swe mice and single-transgenic tgSwe mice. Our results show that heparanase overexpression was associated with a lowered cerebral Aβ and amyloid burden, proposing that codeposition of HS with Aβ is of relevance to AD pathogenesis. The effect is not likely to be a result of altered AβPP processing but is instead caused by attenuated Aβ aggregation processes because of fragmentation of the HS side chains of HSPGs by heparanase.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Animals

The genotype and phenotypes of a homozygous mouse strain overexpressing human heparanase under a β-actin promoter (tgHpa) have been described previously (15). AβPP-transgenic mice harboring only the Swedish double mutation (K670N/M671L (27)), the tgSwe model, is a relatively mild model of amyloidosis with onset of plaque deposition at around 12 months of age (25, 26). The animals used for this study, single-transgenic tgSwe and double-transgenic tgHpa*Swe mice, were all bred on a pure C57BL/6J background. Experimental groups were matched for age and sex. Animals were housed with free access to food and water in a controlled environment at the animal facility of the Biomedical Center, Uppsala University, Sweden. All experiments were performed under local ethics regulations for animal welfare (Ethical Permit C239/11).

While under deep anesthesia (0.4 ml tribromoethanol (Avertin), 25 mg/ml), mice were transcardially perfused with PBS before decapitation. One brain hemisphere was quickly frozen and stored at −80 °C until use for biochemical analyses. The other hemisphere was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight (ON) at 4 °C. Fixed brain hemispheres were subsequently cryoprotected via sequential immersion in 10%, 20%, and 30% (w/v) sucrose each for 24 h at 4 °C. Coronal sections (20 μm) were prepared from the fixed and cryoprotected tissue with a sledge microtome (American Optical) and stored at 4 °C in PBS with 10 mm sodium azide for later histological analyses.

For quantification of the Aβ and amyloid plaque burden as well as CAA, HS, and heparanase expression studies, 15-month-old tgSwe (n = 17) and tgHpa*Swe (n = 17) mice of both genders were used. For metabolic analyses of AβPP processing with Western blot analyses and Aβ ELISAs, 2- to 3-month-old mice of both genders were used (in total, eight tgSwe and 12 tgHpa*Swe mice).

Immunohistochemistry

Coronal sections of brains were fixed on Superfrost Plus glass slides (catalog no. 631-9483, VWR, Radnor, PA) before staining. For immunohistochemistry (IHC) of the Aβ burden, the tissue slides were incubated in prewarmed 25 mm citrate buffer (pH 7.3) for 5 min at 82 °C. IHC tissue slides incubated later with Aβx-40 and Aβx-42 antibodies (7) were immersed in 70% formic acid for 5 min at room temperature. The slides were blocked with serum-free Dako block (catalog no. X0909, Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) in PBS with 0.3% H2O2 and incubated ON at 4 °C with primary antibody (0.64 μg/ml polyclonal rabbit anti-Aβx-40 or 0.5 μg/ml polyclonal rabbit anti-Aβx-42, both diluted in PBS with 0.1% Tween 20 (PBS-T)). The tissue slides were subsequently incubated for 30 min at room temperature with 5 μg/ml biotinylated anti-rabbit IgG (catalog no. BA-1000; Vector Laboratories, Inc., Burlingame, CA) in PBS-T. Streptavidin HRP (catalog no. 3310-9, Mabtech, Nacka Strand, Sweden) and NOVA-red (catalog no. SK-4800, Vector Laboratories) were used for visualization. The same protocol was used for staining with anti-HS antibody 10E4 (0.5 μg/ml, catalog no. H1890, USBiological, Salem, MA).

The polyclonal rabbit antibodies anti-8 (0.3 μg/ml) (28) or 63 (0.05 μg/ml) were used for immunohistochemical staining of heparanase overexpression in the brain. The same protocol was followed as above, but there was no pretreatment with citrate buffer and formic acid.

A monoclonal mouse antibody (catalog no. MAB1580, Merck Millipore, Billerica, MA) was used for immunohistochemical staining of early and mature oligodendrocytes. The tissue slides were blocked with serum-free Dako Block (catalog no. X0909, Dako) in PBS with 0.3% H2O2 and with M.O.M. mouse Ig blocking reagent and M.O.M. protein concentrate (catalog no. MKB-2202, Vector Laboratories). The slides were incubated ON at 4 °C with MAB1580 diluted 1:500 in M.O.M. diluent in PBS-T. Subsequently, the slides were incubated for 8 min at room temperature with 5 μg/ml biotinylated anti-mouse IgG (catalog no. BA-9200, Vector Laboratories) diluted in M.O.M. diluent in PBS-T. Streptavidin-HRP (catalog no. 3310-9, Mabtech) and NOVA-red (catalog no. SK-4800, Vector Laboratories) were used for visualization.

Immunofluorescence

To determine which cells overexpress heparanase, multiple fluorescence stainings were performed. Coronal sections of brains were fixed on Superfrost Plus glass slides (catalog no. 631-9483; VWR) before staining.

Heparanase and Astrocytes

For triple fluorescence with polyclonal rabbit anti-heparanase anti-8 antibody, monoclonal mouse anti-glial fibrillary acidic protein (anti-GFAP) antibody (catalog no. MAB11287, Abnova, Taipei City, Taiwan) and Methoxy-04 amyloid stain, the tissue slides were blocked with serum-free Dako Block (catalog no. X0909, Dako) in PBS with 0.3% H2O2, M.O.M. mouse Ig blocking reagent, and M.O.M. protein concentrate (catalog no. MKB-2202, Vector Laboratories). The slides were incubated ON at 4 °C with a mixture of the primary antibodies (0.57 μg/ml anti-GFAP and 1 μg/ml anti-heparanase anti-8) diluted in M.O.M. diluent with PBS-T. Subsequently, the slides were incubated with a mixture of the secondary antibodies (2 μg/ml highly cross-adsorbed goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 594 (catalog no. A-11032, Invitrogen) and 2 μg/ml goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 (catalog no. A-11008, Invitrogen), both diluted in M.O.M. diluent with PBS-T) for 15 min at room temperature in the dark. Tissue slides were treated for 30 min with 10 μg/ml Methoxy-04 at room temperature before being quickly dipped in 70% ethanol and mounted with Slowfade Gold antifade reagent (catalog no. S36937, Molecular Probes, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA).

Heparanase and Neurons

Double fluorescence with 1 μg/ml anti-heparanase anti-8 antibody and 1 μg/ml monoclonal mouse anti-neuronal nuclei antibody (catalog no. MAB377, Merck Millipore) was performed likewise.

Heparanase and Microglia

Triple fluorescence was performed with polyclonal rabbit anti-heparanase 63 antibody (0.2 μg/ml), 10 μg/ml Methoxy-04 dye, and either 3 μg/ml DyLight 488 tomato lectin (catalog no. DL-1174, Vector Laboratories) or 0.5 μg/ml goat anti-microglia Iba1 antibody (catalog no. ab5076, Abcam, Cambridge, UK). The experimental procedure was otherwise equal to the other IHC stainings. 2 μg/ml donkey anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 594 (catalog no. A-21207, Invitrogen) was used for detecting the anti-heparanase antibody, whereas 2 μg/ml donkey anti-goat Alexa Fluor 488 (catalog no. A-11055, Invitrogen) was used for detecting Iba1.

For investigating colocalization of HS with Aβx-42, IHC was performed with 1 μg/ml monoclonal mouse anti-HS 10E4 antibody (catalog no. H1890, USBiological) and 0.5 μg/ml polyclonal rabbit anti-Aβx-42 antibody, both diluted in M.O.M. diluent with PBS-T. As secondary antibodies, 2 μg/ml goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 594 (A-11032, Invitrogen) and 2 μg/ml goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 (catalog no. A-11034, Invitrogen) were used. Otherwise, the method was the same as for the other immunofluorescence procedures.

Congo Red

Coronal sections of brains were fixed on Superfrost Plus glass slides (catalog no. 631-9483, VWR) before staining. For Congo red staining of the amyloid burden, tissue slides were immersed for 5 min in saturated alcoholic sodium chloride solution (4% (w/v) NaCl in 80% ethanol) and subsequently for 30 min in 1% (w/v) Congo red (catalog no. C6277, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) in saturated alcoholic sodium chloride solution before being washed, dehydrated, and mounted with cover slides.

Quantification of Cerebral Amyloidosis and HS

All IHC and Congo red-stained sections were visualized and photographed using Olympus BX53 fitted with an Olympus DP73 digital camera. Image-Pro Plus 7.0 software (Media Cybernetics) was used for quantification of the Aβ and amyloid plaque burden as well as CAA in the cerebral cortex. The investigator was blinded to the identity of the mouse brains. A constant threshold was maintained across images from the same staining to ensure comparability between tissue slides. For quantification of Aβx-40, Aβx-42, and amyloid burden, multiple sections (n = 3–4) from each animal were analyzed, and internal standards were used to lower experimental variability between individual glass slides. For measuring HS-immunoreactive intensity, sections from all mice were stained together, and the optical density (OD) of HS in amyloid deposits from two sections from each animal was measured with a constant threshold using Image-Pro Plus 7.0.

Mouse Brain Homogenization

Brains were extracted sequentially, resulting in a Tween 20 fraction and an SDS fraction to ensure that both AβPP and Aβ were present in the extracts and to largely separate soluble AβPP fragments from membrane-bound AβPP. In short, brains were homogenized manually with a Potter-Elvehjem 10 ml homogenizer (catalog no. 432-5015, VWR) in 0.2% Tween 20 in TBS with complete mini protease inhibitor mixture (catalog no. 04-693-116-001, Roche) before the homogenate was centrifuged at 100,000 × g using a Beckman Optima LE-80K ultracentrifuge with a Sw-60Ti rotor. The supernatant Tween fraction was stored at −80 °C until further use. The pellet was resuspended in 1% (w/v) SDS with complete mini protease inhibitor and again homogenized. The homogenate was centrifuged at 100,000 × g, and the supernatant, after SDS extraction, was stored at −80 °C until further use.

Characterization of HS from Mouse Brain

Two 2-month-old tgSwe and tgHpa*Swe mice were given an intraperitoneal injection with 100 mCi of Na35SO4 (catalog no. NEX041H, PerkinElmer Life Sciences). After 1 h, the mice were sacrificed, and the brains dissected as described previously. Following homogenization, the brain lysates were incubated ON at 55 °C with 0.5 mg of protease in 0.5 ml of buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 1 mm CaCl2, and 1% Triton X-100).

Subsequently, the samples were heated at 95 °C for 5 min to inactivate the protease, and benzonase (12.5 units) was added to degrade DNA. After 10 min of centrifugation at 8000 × g, the resulting supernatants were applied to a DEAE Sephacel column (catalog no. 17-0500-01, GE Healthcare) pre-equilibrated with an equilibration buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) and 0.15 m NaCl). The columns were then washed serially with equilibration buffer, followed by a washing buffer (50 mm NaAc (pH 4.5) and 0.25 m NaCl), and, finally, with an elution buffer (50 mm NaAc (pH 4.5) and 2 m NaCl). The eluates were desalted on a PD-10 column (catalog no. 17-0851-01, GE Healthcare) in 10% ethanol and then lyophilized. The yielded products were treated with chondroitinase ABC (catalog no. 100330, Serkagaku) and reapplied to the DEAE Sephacel column to remove degraded chondroitin sulfate and then desalted on a PD-10 column. For HS size determination, the purified HS products were applied on a Superose 12 column (catalog no. 17-5173-01, GE Healthcare) connected to a HPLC system.

ELISA

For quantification of Aβx-40 and Aβx-42, 96-well Maxisorp plates (catalog no. 442404, Nunc, Thermo Scientific) were used for ELISAs and coated ON at 4 °C on a shaker with a monoclonal capturing antibody that recognizes Aβ3–8 (1C3, 150 ng/well (29)). The plates were blocked with 1% BSA for 1 h at 37 °C on a shaker. Tween and SDS extracts from brains from 2- to 3-month-old mice were mixed 1:1 and diluted 1:30 in 0.1% BSA for the Aβx-40 ELISA and 1:40 in 0.1% BSA for the Aβx-42 ELISA. Extracts were incubated on the plates for 2 h at room temperature on shaker. Biotinylated polyclonal rabbit anti-Aβx-42 or anti-Aβx-40 detection antibody was incubated at a final concentration of 0.32 μg/ml or 0.66 μg/ml, respectively, for 1 h at room temperature on shaker before being detected with a 1:2000 dilution of streptavidin HRP (catalog no. 3310-9, Mabtech) for 30 min at room temperature on a shaker. A standard curve was made using either Aβ1–40 or Aβ1–42 peptide (catalog nos. 62-0-78B and 62-0-80B, respectively; American Peptide Co., Sunnyvale, CA) and the capturing and detecting antibodies mentioned previously. The ELISA was visualized using K-blue aqueous substrate (catalog no. 331177, Neogen, Lansing, MI), and the enzymatic reaction was terminated after 12 min with 1 m H2SO4. Optical density was measured at 450 nm using a SpectraMax 190 plate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

Western Blots

For semiquantification of levels of cerebral soluble β-cleaved AβPP (sAβPPβ) and heparanase expression, protein samples (≈40 μg of protein/well) from Tween 20 extracts of the cerebral cortices from 2- to 3-month-old mice were separated on 10% SDS-PAGE gels and transferred onto PVDF Immobilon-P membranes (catalog no. IPVH00010, Merck Millipore) by electrophoresis. Membranes were blocked for 1 h with 5% nonfat dry milk in 50 mm TBS (pH 7.4) with 0.05% Tween 20 and incubated ON at 4 °C with the appropriate primary antibody. Anti-sAβPPβ antibody (sw192 at 0.1 μg/ml, neoepitope-specific for β-cleaved sAβPP-Swe (30)) was used for detecting β-secretase activity. The anti-heparanase antibodies 1453 and 733 (1 μg/ml) were used for detection of heparanase overexpression. The 1453 antibody binds to both latent (65 kDa) and active (50 kDa) heparanase, whereas the 733 antibody only binds to the 50-kDa band (31). Both antibodies detect human and mouse heparanase. Signals were developed with SuperSignal Dura substrate (catalog no. 34075, Thermo Scientific) and captured by the ChemidocTM MP system (catalog no. 170-8280, Bio-Rad). Images of blots were analyzed using ImageJ version 1.46 (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/index.html).

Aβ1–42 Monomer Preparation

An Aβ1–42 monomer solution (catalog no. 62-0-80B, American Peptide Co.) was prepared by dissolving the provided powder in 10 mm freshly prepared, cold NaOH. Aβ1–42 was kept cold at all times to avoid uncontrolled and unwanted aggregation. The 100 μm Aβ1–42 solution was centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 5 min at 4 °C to separate possible aggregates, and the supernatant was aliquoted and frozen at −80 °C until further use. Low-binding pipette tips (Axygen Maxymum Recovery; catalog nos. 613-0458, 613-0450, and 613-0439; VWR) and Eppendorf tubes (Protein LoBind, catalog nos. 525-0132 and 525-0133, VWR) were used at all times to avoid binding of Aβ to plastic surfaces.

Thioflavin T Aggregation Assay

We performed an in vitro Thioflavin T assay to investigate the effect of the HS-like molecule heparin on Aβ1–42 aggregation. Thioflavin T aggregation assays in the absence of Aβ1–42 served as negative control experiments. Each sample was analyzed in quadruplicates. A 96-well non-binding fluorescence immunoassay microplate (catalog no. 655900, Greiner Bio-One, Frickenhausen, Germany), low-binding pipette tips (Axygen Maxymum Recovery, VWR), and Eppendorf tubes (Protein LoBind, VWR) were used when handling Aβ1–42 to avoid unspecific binding. A Thioflavin T (catalog no. T3516, Sigma-Aldrich) solution was freshly prepared to ensure full fluorescent capacity. Thioflavin T powder was dissolved in special PBS with less saline (137 mm NaCl, 2.7 mm KCl, 100 mm Na2HPO4 × 2 H2O and 20 mm KH2PO4) to avoid the inhibitory effect of saline on the aggregation process. Aβ1–42 was thawed on ice and centrifuged for 15 min in a precooled 4 °C centrifuge to remove unwanted aggregates. A final concentration of 0.3 μm Thioflavin T in special 1× PBS and 10 μm Aβ1–42 was used. A final concentration of 100 μm heparin (a gift from Shenzhen HepaLink Pharmaceuticals, China) was added to the appropriate wells 4 h after Aβ1–42 (when the Thioflavin T signal from Aβ1–42 aggregation was 100% above background). Aggregation was allowed to proceed at room temperature on a shaker, and progress was measured at time 0 and onwards with an EnVision2104 multilabel reader (catalog no. 2104-0010, PerkinElmer Life Sciences) with excitation at 442 nm (cyan fluorescent protein 430/24 filter, catalog no. 2100-5840, PerkinElmer Life Sciences) and emission at 482 (cyan fluorescent protein 470/24 filter, catalog no. 2100-5850, PerkinElmer Life Sciences).

Statistics

For comparing the Aβ and amyloid burden and CAA from histological staining, a non-parametric Mann-Whitney test was used. A Mann-Whitney test was also used for comparing Aβ levels in young mice with ELISA, whereas an unpaired Student's t test was used for comparing sAβPPβ Western blot results, HS-immunoreactivity, and Thioflavin T data. Results from nonparametric data are presented as median (interquartile range), whereas data from normally distributed data are presented as mean ± S.E. All given p values are two-tailed.

RESULTS

Overexpression of Heparanase in Neurons and Astrocytes in Double-transgenic Mice

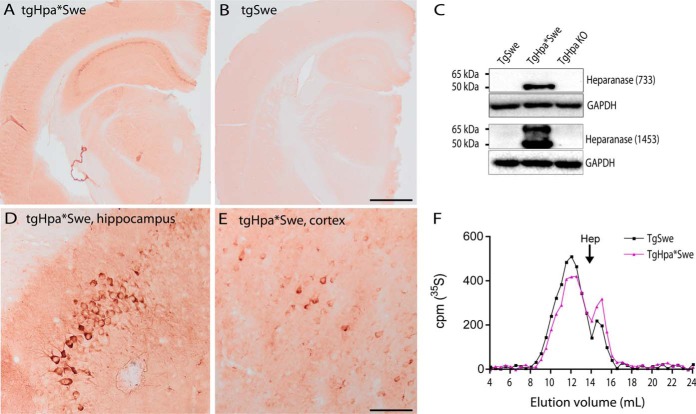

IHC with an anti-heparanase antibody (63) raised against the whole 65-kDa heparanase gave a strong cell-specific staining in tgHpa*Swe mice, but not in tgSwe mice (Fig. 1, A and B). Particularly pyramidal neurons in the hippocampus and cerebral cortex showed high heparanase expression (Fig. 1, D and E). Western blotting with the anti-heparanase antibody 1453 confirmed the expression of both the latent (65-kDa) and the active (50-kDa) forms of heparanase in tgHpa*Swe mouse brain compared with tgSwe and tgHpa knockout mouse brains. This was further confirmed by using another anti-heparanase antibody detecting only the active form of heparanase (733) (Fig. 1C). Endogenous murine heparanase expression in tgSwe mice was below the level of detection of this method. The effect of overexpressed heparanase in tgHpa*Swe mice is demonstrated by size analysis of HS. Gel chromatography analysis of 35S-labeled HS isolated from whole brain shows increased smaller HS fragments from young tgHpa*Swe mice compared with young tgSwe mice (Fig. 1F). The limited reduction in HS chain length is presumably due to anatomically restricted expression in some brain areas. On this note, the reduction in HS chain length in the cortex and hippocampus is expected to be more pronounced because of a higher expression level of heparanase in these regions (Fig. 1, A and B).

FIGURE 1.

Heparanase expression and HS fragment analysis in the transgenic mouse brain. Immunohistochemistry with the anti-heparanase antibody 63 in tgHpa*Swe and tgSwe mice revealed overexpression of heparanase in tgHpa*Swe mice, particularly in the pyramidal cell layer of the hippocampus but also diffusely in gray matter (A). Only a faint, nonspecific stain is seen in tgSwe brain (B). Higher magnification images of the tgHpa*Swe brain show neuronal staining in the CA3 region of the hippocampus (D) and in the lower lamina in the cerebral cortex (E). Western blot analysis with the anti-heparanase antibody 733 detected active heparanase (50 kDa), whereas antibody 1453 detected both latent (65-kDa) and active heparanase in whole brain lysates of tgHpa*Swe mice (C). Endogenous mouse heparanase in tgSwe mice was below the detection level. The sizes of metabolically 35S-labeled HS isolated from whole brains of 2-month-old tgSwe and tgHpa*Swe mice were analyzed by gel chromatography (F). The TgHpa*Swe mouse brain contained fewer long HS fragments and more short HS fragments than the tgSwe mouse brain, indicating that heparanase overexpression led to degradation of HS in vivo. Hep, the elution position of heparin (around 14 kDa); TgHpa KO, brain from heparanase knockout mouse. Scale bars = 1 mm (A and B) and 100 μm (D and E).

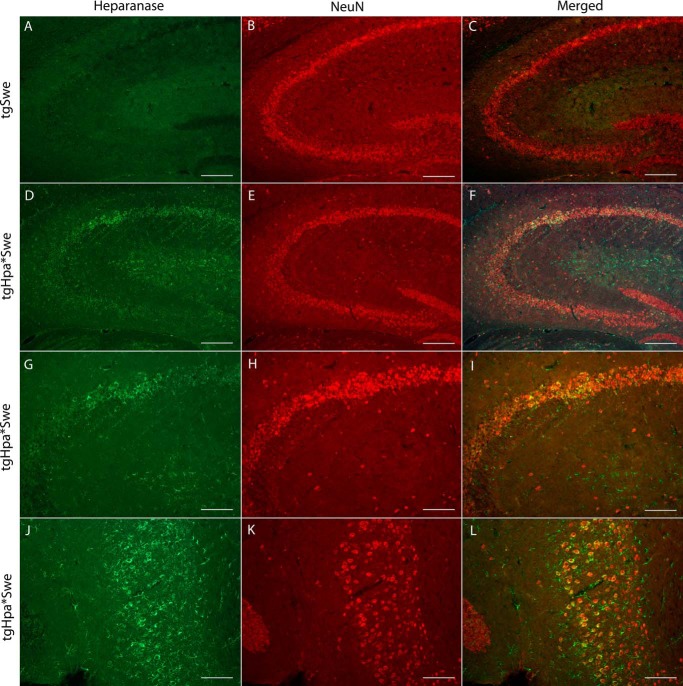

To verify the specific cellular localization of heparanase overexpression in the brains of our double-transgenic tgHpa*Swe mice, we performed immunofluorescence with an anti-heparanase antibody specific for the C-terminal of the 8-kDa heparanase subunit (28) combined with an anti-neuronal nuclei antibody. Heparanase was found expressed in neurons of tgHpa*Swe mice (Fig. 2, D–L). No immunostaining above background was observed in single-transgenic tgSwe mice (Fig. 2, A–C).

FIGURE 2.

Neuronal heparanase expression in the tgHpa*Swe mouse brain. Immunofluorescence with the anti-heparanase antibody anti-8 (green) and anti-neuronal nuclei antibody (red) in the brains of 15-month-old single-transgenic tgSwe (A–C) and double-transgenic tgHpa*Swe (D–L) mice. Heparanase was found to be overexpressed in some neurons in tgHpa*Swe mice, here shown in the hippocampus (D–I) and in the dentate gyrus (J–L). Heparanase-overexpressing neurons were also found in other regions of the brains. Scale bars = 200 μm (A–F) and 100 μm (G–L).

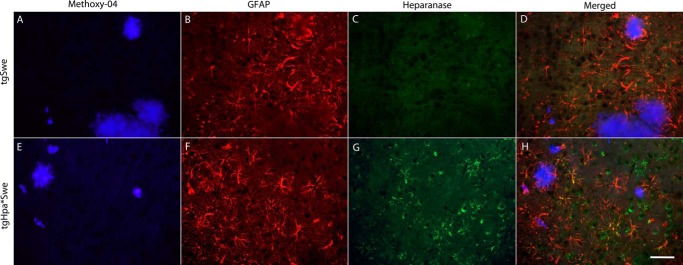

To further investigate expression, we also performed immunofluorescence with anti-heparanase and anti-GFAP antibodies together with a fluorescent amyloid dye, Methoxy-04. There was some colocalization of GFAP and heparanase in tgHpa*Swe mice, showing that heparanase is overexpressed in some astrocytes (Fig. 3, E–H); all of the protoplasmic type. In contrast, GFAP-positive astrocytes in tgSwe mice did not show heparanase-specific staining (Fig. 3, A–D). We did not find evidence of colocalization between heparanase and markers for microglia or oligodendrocytes.

FIGURE 3.

Astrocytic heparanase expression in tgHpa*Swe mice. Immunofluorescent detection of positive staining with Methoxy-04 (blue), anti-GFAP (red), and anti-heparanase (green) antibodies on sections in the cerebral cortex from 15-month-old single-transgenic tgSwe (A–D) and double-transgenic tgHpa*Swe mice (E–H). GFAP-positive astrocytes were found in both groups of mice. A signal specific to heparanase was seen only in the double-transgenic mice and was found to colocalize with some GFAP-positive astrocytes. Scale bar = 50 μm.

Heparanase Overexpression in tgHpa*Swe Mice Reduces the Aβ Burden and Heparan Sulfate in Amyloid Plaques

HS and HSPGs are found in senile plaques of both human AD and AβPP-transgenic mouse brains (3, 7), but their pathogenic roles remain unclear. To investigate the involvement of HS in Aβ plaque formation, 15-month-old tgSwe and tgHpa*Swe mice were sacrificed for examination of the Aβ burden in the brain. For immunohistochemical staining of brain sections, we used an anti-Aβx-40 antibody that detects all cored plaques and vascular deposits and an anti-Aβx-42 antibody that recognizes cored and diffuse plaques (7).

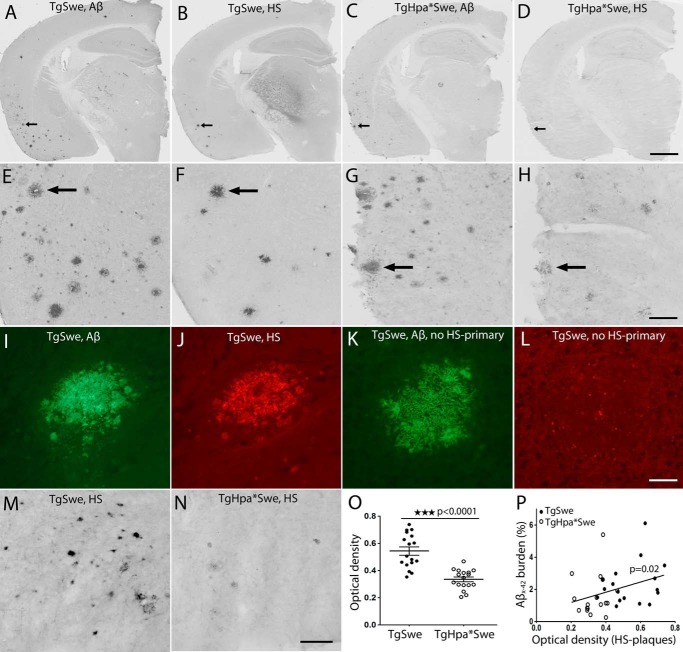

Semiadjacent IHC tissue sections were stained simultaneously with anti-Aβx-42 and an anti-HS antibody, 10E4, to examine the localization of HS in pathological lesions. HS was found localized with amyloid cores in some Aβ deposits (Fig. 4, A–L). Furthermore, we measured the OD of amyloid-associated HS in both groups of mice (Fig. 4, M and N). Lower HS immunoreactivity was found in tgHpa*Swe mice (mean ± S.E., OD 0.54 (0.03), n = 17) than tgSwe mice (OD 0.33 (0.02), n = 17), indicating that there is less HS associated in amyloid plaques in heparanase-overexpressing mice (p < 0.0001, Fig. 4O). We also found a significant correlation between the OD of HS immunoreactivity in senile plaques and cortical Aβx-42 burden (p = 0.02, Fig. 4P).

FIGURE 4.

HS and Aβx-42 plaque colocalization and reduced histological HS staining in amyloid plaques in the tgHpa*Swe mouse brain. IHC showed the localization of Aβx-42 (A, C, E, and G) with HS-immunoreactive deposits (B, D, F, and H) in semiadjacent brain sections of tgSwe (A, B, E, and F) and tgHpa*Swe (C, D, G, and H) mice that were stained simultaneously. A fainter HS staining of amyloid deposits is seen in tgHpa*Swe (D and H) compared with tgSwe mice (B and F). The arrows in A–D correspond to the arrows in E–H. Double-immunofluorescence using Aβx-42 and HS antibodies in tgSwe mice shows plaque colocalization (I and J). A negative control for HS was performed by staining with Aβx-42 antibody and both secondary antibodies but excluding the primary anti-HS antibody (K and L). Plaque-associated IHC staining of HS from representative mice (M and N) and quantification of the OD of HS staining in plaques showed that double-transgenic tgHpa*Swe mice had significantly weaker HS immunoreactively stained plaques than tgSwe mice (O) (p < 0.0001). This indicates that plaque-associated HS is reduced quantitatively and/or more fragmented in tgHpa*Swe brain compared with tgSwe brain. The optical density of HS staining correlated well with the Aβx-42 burden in the cerebral cortex (P) (p = 0.02), particularly among tgSwe mice. Scale bars = 800 μm (A–D), 160 μm (E–H), 50 μm (I–L), and 50 μm (M and N). Lines indicate mean ± S.E. (O).

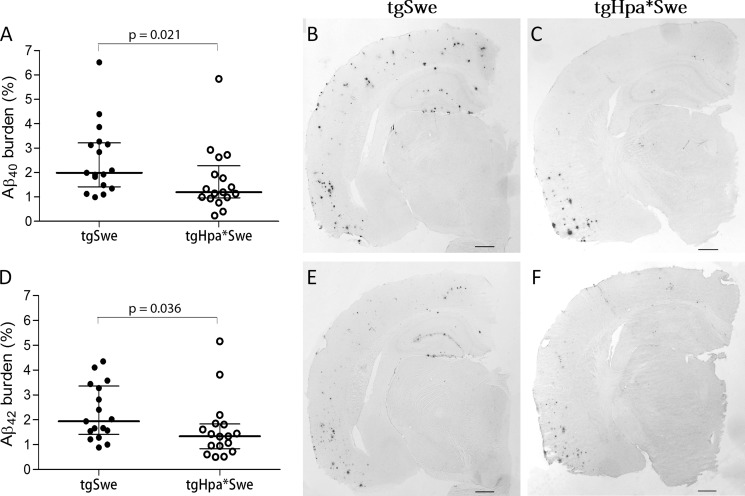

The area fraction of the Aβ burden in the cerebral cortex from IHC sections was also measured with quantitative image analysis. The results show a significantly lower Aβx-40 burden in tgHpa*Swe mice (median (interquartile range), 1.19% (1.32) (n = 17)) compared with tgSwe mice (1.99% (1.80) (n = 17); p = 0.021; Fig. 5, A–C). The Aβ42-burden was also significantly lower in tgHpa*Swe mice (1.34% (1.00) (n = 17)) compared with tgSwe mice (1.94% (1.94) (n = 17); p = 0.039; Fig. 5, D–F).

FIGURE 5.

Aβ deposition in 15-month-old double-transgenic tgHpa*Swe mice and single-transgenic tgSwe mice. Quantitative image analysis showed that both Aβx-40 (A–C) and Aβx-42 deposition (D–F) was lower in double-transgenic tgHpa*Swe (n = 17) than in single-transgenic tgSwe mice (n = 17). Lines indicate medians with interquartile range. Scale bars = 1 mm.

Lower Parenchymal and Cerebrovascular Amyloid Burden in Double-transgenic Mice

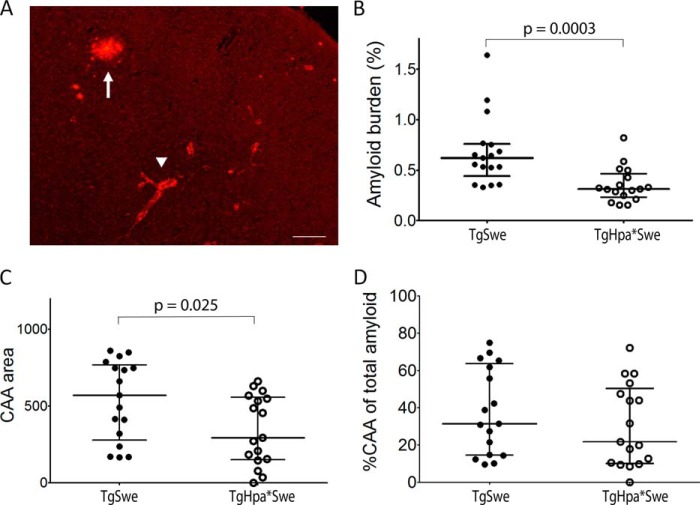

HS and HSPGs preferentially colocalize with the amyloid core of mature plaques, a small region at the center of most Aβ deposits in both the AD brain and AβPP transgenic models (3–7). To further characterize the Aβ plaques, we stained adjacent sections of the mouse brains with Congo red fluorescent dye, which detects only the amyloid core of mature plaques. Positive staining was detected in both groups of 15-month-old single- and double-transgenic mice. Quantification revealed a significantly lower Congo red-positive amyloid burden in tgHpa*Swe mice compared with tgSwe mice (median (interquartile range), 0.31% (0.23) (n = 17) versus 0.62% (0.32) (n = 17); p = 0.0003; Fig. 6B).

FIGURE 6.

Congo red histological staining of the amyloid burden in 15-month-old double-transgenic tgHpa*Swe and single-transgenic tgSwe mice. A, plaques and CAA in a tgSwe mouse. The arrowhead indicates CAA, and the arrow indicates plaque. Scale bar = 200 μm. Quantitative image analysis showed that total cortical amyloid (CAA plus plaque area) (B) as well as the CAA burden (C) was lower in double-transgenic tgHpa*Swe mice (n = 17) than in single-transgenic tgSwe mice (n = 17). The percentage of CAA of the total amyloid burden in the cerebral cortex showed no difference between single- and double-transgenic mice (D). Lines indicate medians with interquartile range.

We also specifically analyzed and compared congophilic CAA in the cerebral cortex. Significantly less CAA was found in tgHpa*Swe mice compared with tgSwe transgenic mice (mean ± S.E., 344 arbitrary units (55) (n = 17) versus 539 arbitrary units (63) (n = 17); p = 0.025; Fig. 6C). However, we found no significant difference in the relative amount in the percentage of CAA to total amyloid staining in cerebral cortex between the two groups of mice (mean ± S.E., 38 % (5.6) (n = 17) versus 31% (5.3) (n = 17); p = 0.32; Fig. 6D).

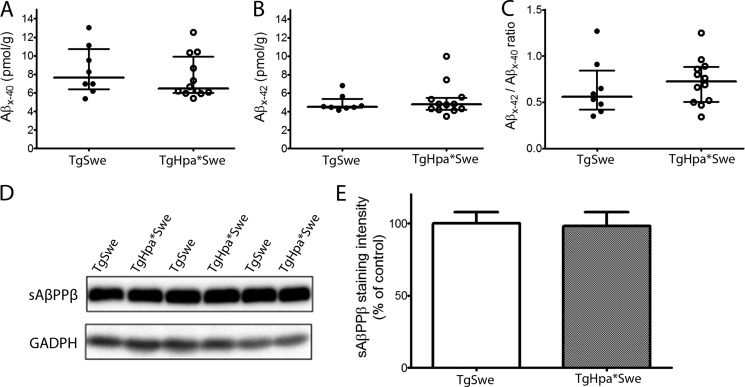

Heparanase Overexpression Did Not Affect Aβ and sAβPPβ Levels in the Brains of Young AβPP Mice

Next we investigated whether innate changes in AβPP production or processing were the cause of the lower Aβ and amyloid deposition seen in double-transgenic mice. Therefore, we quantified the levels of Aβx-40 and Aβx-42 in whole brains from 2- to 3-month-old tgSwe and tgHpa*Swe mice by ELISAs. We used a 1:1 mix of Tween and SDS extracts to obtain both intracellular and extracellular Aβ. There was essentially no difference between tgSwe and tgHpa*Swe mice at this age for Aβx-40 (median (interquartile range), 7.63 (4.44) pmol/g (n = 8) versus 6.47 (3.92) pmol/g (n = 12); p = 0.46; Fig. 7A), Aβx-42 (4.53 (0.96) pmol/g (n = 8) versus 4.78 (1.28) pmol/g; p = 0.97; Fig. 7B), or the Aβx-42/Aβx-40 ratio (0.56 (0.43) pmol/g (n = 8) versus 0.73 (0.38) pmol/g (n = 12); p = 0.46; Fig. 7C).

FIGURE 7.

AβPP processing in double-transgenic tgHpa*Swe and single-transgenic tgSwe mice. Shown are ELISA data on steady-state levels of Aβx-40 (A), Aβx-42 (B), and Aβx-42/Aβx-40 (C) in the brains of 2- to 3-month-old single-transgenic tgSwe (n = 8) and double-transgenic tgHpa*Swe mice (n = 12). There was no difference in the levels of Aβx-40 and Aβx-42 or in the ratio of Aβx-42:Aβx-40 between the two groups of mice. Lines indicate medians with interquartile ranges. Western blot analysis on the levels of sAβPPβ in 2- to 3-month-old single-transgenic tgSwe (n = 8) and double-transgenic tgHpa*Swe (n = 12) mice (D) revealed no difference in the levels of sAβPPβ between the two groups of mice (E). Error bars represent means ± S.E.

Because HS has been reported to directly interact with β-secretase and, thereby, regulate AβPP processing (11), we also analyzed the major product of this enzymatic activity, sAβPPβ, by Western blot analysis with Tween extracts of the brain tissues. Again, there was no difference in the steady-state levels of sAβPPβ between the two groups (mean ± S.E., 100.0 (7.8) for tgSwe mice (n = 8) versus 98.2 (9.4) for tgHpa*Swe mice (n = 12); Fig. 7, D and E).

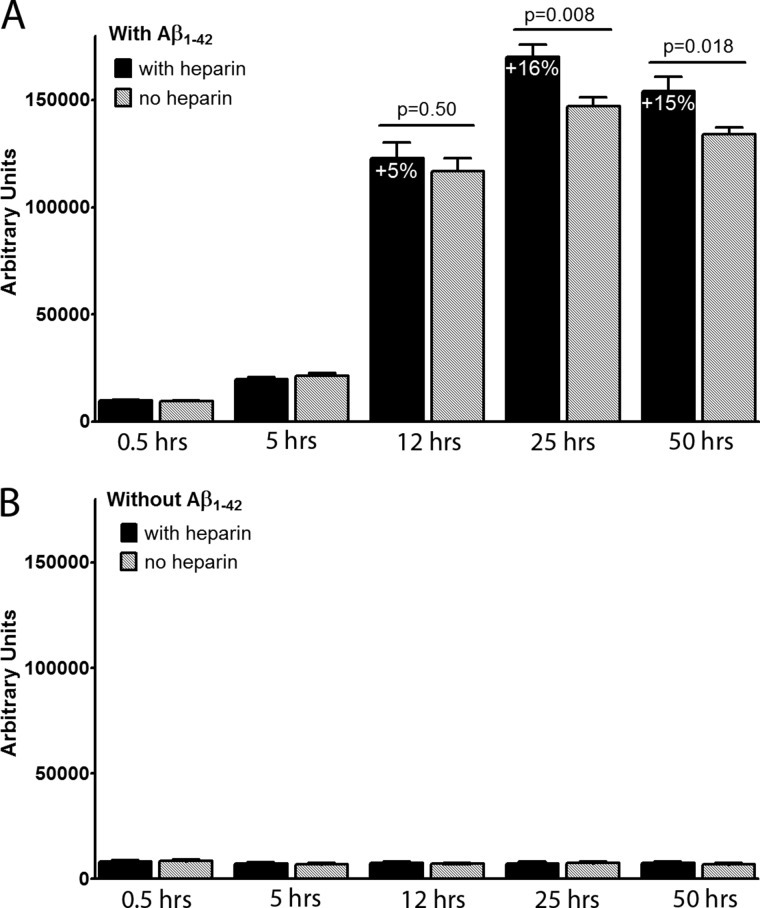

Heparin Increases Aβ1–42 Aggregation in Vitro

Finally, we examined whether heparin, an HS-like molecule, would affect Aβ aggregation in an in vitro system. Heparin was added to Aβ1–42 in a Thioflavin T aggregation assay when Aβ1–42 had started to aggregate, but far before log phase. The Thioflavin T signal reflects Aβ fibril formation. We found that 100 μm heparin added after 4 h significantly increased Aβ1–42 aggregation (16% higher in presence of heparin at 25 h, p = 0.008, Fig. 8A). The effect remained at 50 h (15%, p = 0.018, Fig. 8A). In the absence of Aβ1–42, heparin did not alter the Thioflavin T signal with time (Fig. 8B). The experiment was repeated twice with quadruplicates.

FIGURE 8.

Effect of heparin (100 μm) on the aggregation of Aβ1–42 (10 μm) in a Thioflavin T (0.3 μm) assay. Heparin, an HS-like molecule, was added to aggregating Aβ1–42 when the Thioflavin T signal had risen 100% above baseline. The experiment was repeated twice, both times with quadruplicates. Heparin significantly increased Aβ1–42 aggregation, and the effect was statistically significant at 25 h (p = 0.008) and remained until assay termination at 50 h (p = 0.018) (A). In the absence of Aβ1–42, heparin did not affect the Thioflavin T signal (B). Error bars represent means ± S.E.

DISCUSSION

HS/HSPGs have been found colocalized with Aβ plaques and CAA in the brain of AD patients and mouse models overexpressing human mutant AβPP (3–6). However, the cause and effect of this codeposition remains unclear. To understand whether HS and HSPGs are active participators of Aβ pathogenesis or simply adhere to and colocalize with Aβ in amyloid plaques, we generated a double-transgenic mouse model overexpressing both human heparanase and human AβPP harboring the Swedish mutation (tgHpa*Swe) by crossing the tgHpa (15) and tgSwe (25, 26) mice. We found that the double-transgenic mice showed overexpression of heparanase in the brain and produced shorter HS fragments. Because heparanase is primarily expressed in the cortex and hippocampus, whereas the HS was isolated from the whole brain, it was anticipated that the HS expressed in the cortex and hippocampus of tgHpa*Swe mice would give a more pronounced reduction in HS chain length. Unfortunately, it is not possible to get a sufficient amount of HS from the subregions of mouse brain because of the limitations of the technique.

The tgSwe mice have been demonstrated to spontaneously develop Aβ plaques in the brain in an age-dependent manner (25, 26). The unique double-transgenic model, tgHpa*Swe, allowed us to directly and non-invasively assess the possible pathophysiological roles of HS in endogenous Aβ deposition. We found that heparanase is overexpressed in neurons and astrocytes in tgHpa*Swe mice but not in oligodendrocytes or microglia. Histological examinations revealed colocalization of HS with amyloid plaques in both groups. The OD of HS-immunoreactive amyloid deposits was reduced significantly in 15-month-old tgHpa*Swe mice compared with age-matched tgSwe mice. This indicates that a lower amount of HS or more fragmented HS is being incorporated in plaques of tgHpa*Swe mice. A lower Aβ40, Aβ42, and amyloid burden was found in the cerebral cortex of 15-month-old tgHpa*Swe mice compared with age-matched tgSwe mice, showing that overexpression of heparanase affects Aβ and amyloid deposition in tgSwe mice.

It has been reported previously that heparin and HS decrease β-secretase activity in vitro by binding to the active site of the enzyme (11). It has also been found that glycosaminoglycans decreased Aβ secretion in primary cortical cell cultures, possibly by affecting both α- and β-secretase pathways (9). In contrast, others showed that heparin increased β-secretase activity in a neuroblastoma cell line (10). Therefore, HS may affect β-secretase activity in the brain, thereby influencing the production of Aβ fragments. In our in vivo study, however, no differences were found in the steady-state levels of Aβx-40, Aβx-42, or sAβPPβ, as measured by ELISAs and Western blot analyses between young single- and double-transgenic mice, indicating that AβPP processing was not affected by heparanase overexpression. Consequently, the reduced amyloid pathology in aged double-transgenic mice is most likely due to obstructed HS-induced Aβ aggregation and deposition.

In vitro studies have shown that heparin and HS promote Aβ aggregation (12, 13), indicating that HS interaction with Aβ may lead to the codeposition observed in human AD brain and mouse models. This effect of HS-induced Aβ aggregation depends on the chain length and degree of sulfation of the HS side chains (17). Heparanase overexpression shortens the HS side chains of HSPGs in tgHpa*Swe mice and, thereby, likely alters the interaction between Aβ and HS so that Aβ fibril formation is disfavored. Stronger HS staining of amyloid plaques in single-transgenic tgSwe mice devoid of human heparanase and a positive correlation with Aβx-42 burden reinforce the view that HS plays an active role in the amyloidogenic process. The observed data support the hypothesis that HSPGs effectively serve to seed extracellular amyloid deposits in vivo. This hypothesis was strengthened by our in vitro experiments in which the HS-like molecule heparin significantly increased Aβ fibril formation in a Thioflavin T assay. In our tgHpa*Swe mice, the lower amyloid pathology is, therefore, likely caused by a less favorable condition for Aβ aggregation. Using Congo red fluorescent dye, we also found less CAA in heparanase-overexpressing mice, a reduction well reflecting the lower parenchymal amyloid burden.

In conclusion, using a unique double-transgenic mouse model, this study clearly shows that HSPGs are actively involved in Aβ deposition in the murine brain because fragmentation of the HS side chains and a lower HS presence in amyloid plaques was associated with less Aβ deposition in heparanase-overexpressing AβPP transgenic mice. The levels of the β-secretase-specific products sAβPPβ and Aβ were not affected in young double-transgenic, heparanase-overexpressing tgHpa*Swe mice compared with single-transgenic tgSwe mice, indicating that the effect of heparanase overexpression on amyloid burden was not caused by altered AβPP processing. Our results do not exclude that HS, in other circumstances, could affect β-secretase activity, as found in vitro by others (9–11). Still, the lower amyloid burden in heparanase-overexpressing mice is likely caused by reduced Aβ aggregation.

Two-photon laser-scanning intravital microscopy (32) or seeding experiments (33) are needed to provide final in vivo proof that the aggregation process is indeed impaired in tgHpa*Swe mice. We regard such experiments to be the subject for separate studies. We do not rule out that additional factors, like differential immune response and HS fragment-mediated Aβ clearance along the perivascular lymphatic drainage pathway (15, 34, 35), also influence parenchymal and cerebrovascular Aβ deposition in double-transgenic mice.

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Lars Lannfelt and the Uppsala University Transgenic Facility for support in developing the tgSwe mouse model and Dr. Reidun Torp for Methoxy-04.

This work was supported by funding from the University of Oslo, by Anders Jahres Stiftelse, by Helse Sør-Øst, by the Civitan Foundation, by a Joint Programme Neurodegenerative Disease Research grant (to L. N. G. N.), by Swedish Heart and Lung Foundation Grant 20110131, by Swedish Research Council Grant K2012-67X-21128-01-4, and by the Polysackaridforskning Foundation (Uppsala) (to J. P. L.).

- AD

- Alzheimer disease

- Aβ

- amyloid-β

- CAA

- cerebral amyloid angiopathy

- HS

- heparan sulfate

- HSPG

- heparan sulfate proteoglycan

- AβPP

- amyloid-β precursor protein

- M.O.M.

- mouse on mouse

- ON

- overnight

- IHC

- immunohistochemistry

- GFAP

- glial fibrillary acidic protein

- sAβPP

- soluble β-cleaved amyloid-β precursor protein

- OD

- optical density.

REFERENCES

- 1. Pepys M. B., Herbert J., Hutchinson W. L., Tennent G. A., Lachmann H. J., Gallimore J. R., Lovat L. B., Bartfai T., Alanine A., Hertel C., Hoffmann T., Jakob-Roetne R., Norcross R. D., Kemp J. A., Yamamura K., Suzuki M., Taylor G. W., Murray S., Thompson D., Purvis A., Kolstoe S., Wood S. P., Hawkins P. N. (2002) Targeted pharmacological depletion of serum amyloid P component for treatment of human amyloidosis. Nature 417, 254–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Potter H., Wefes I. M., Nilsson L. N. (2001) The inflammation-induced pathological chaperones ACT and apo-E are necessary catalysts of Alzheimer amyloid formation. Neurobiol. Aging 22, 923–930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. O'Callaghan P., Sandwall E., Li J. P., Yu H., Ravid R., Guan Z. Z., van Kuppevelt T. H., Nilsson L. N., Ingelsson M., Hyman B. T., Kalimo H., Lindahl U., Lannfelt L., Zhang X. (2008) Heparan sulfate accumulation with Aβ deposits in Alzheimer's disease and Tg2576 mice is contributed by glial cells. Brain Pathol. 18, 548–561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Snow A. D., Wight T. N. (1989) Proteoglycans in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease and other amyloidoses. Neurobiol. Aging 10, 481–497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Snow A. D., Willmer J., Kisilevsky R. (1987) Sulfated glycosaminoglycans: a common constituent of all amyloids? Lab. Invest. 56, 120–123 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. van Horssen J., Kleinnijenhuis J., Maass C. N., Rensink A. A., Otte-Höller I., David G., van den Heuvel L. P., Wesseling P., de Waal R. M., Verbeek M. M. (2002) Accumulation of heparan sulfate proteoglycans in cerebellar senile plaques. Neurobiol. Aging 23, 537–545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lord A., Philipson O., Klingstedt T., Westermark G., Hammarström P., Nilsson K. P., Nilsson L. N. (2011) Observations in APP bitransgenic mice suggest that diffuse and compact plaques form via independent processes in Alzheimer's disease. Am. J. Pathol. 178, 2286–2298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Watson D. J., Lander A. D., Selkoe D. J. (1997) Heparin-binding properties of the amyloidogenic peptides Aβ and amylin: dependence on aggregation state and inhibition by Congo red. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 31617–31624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cui H., Hung A. C., Klaver D. W., Suzuki T., Freeman C., Narkowicz C., Jacobson G. A., Small D. H. (2011) Effects of heparin and enoxaparin on APP processing and Aβ production in primary cortical neurons from Tg2576 mice. PLoS ONE 6, e23007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Leveugle B., Ding W., Durkin J. T., Mistretta S., Eisle J., Matic M., Siman R., Greenberg B. D., Fillit H. M. (1997) Heparin promotes β-secretase cleavage of the Alzheimer's amyloid precursor protein. Neurochem. Int. 30, 543–548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Scholefield Z., Yates E. A., Wayne G., Amour A., McDowell W., Turnbull J. E. (2003) Heparan sulfate regulates amyloid precursor protein processing by BACE1, the Alzheimer's β-secretase. J. Cell Biol. 163, 97–107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Castillo G. M., Lukito W., Wight T. N., Snow A. D. (1999) The sulfate moieties of glycosaminoglycans are critical for the enhancement of β-amyloid protein fibril formation. J. Neurochem. 72, 1681–1687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cotman S. L., Halfter W., Cole G. J. (2000) Agrin binds to β-amyloid (Aβ), accelerates aβ fibril formation, and is localized to Aβ deposits in Alzheimer's disease brain. Mol. Cell Neurosci. 15, 183–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Snow A. D., Sekiguchi R., Nochlin D., Fraser P., Kimata K., Mizutani A., Arai M., Schreier W. A., Morgan D. G. (1994) An important role of heparan sulfate proteoglycan (Perlecan) in a model system for the deposition and persistence of fibrillar A β-amyloid in rat brain. Neuron 12, 219–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhang X., Wang B., O'Callaghan P., Hjertström E., Jia J., Gong F., Zcharia E., Nilsson L. N., Lannfelt L., Vlodavsky I., Lindahl U., Li J. P. (2012) Heparanase overexpression impairs inflammatory response and macrophage-mediated clearance of amyloid-beta in murine brain. Acta Neuropathol. 124, 465–478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bishop J. R., Schuksz M., Esko J. D. (2007) Heparan sulphate proteoglycans fine-tune mammalian physiology. Nature 446, 1030–1037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Esko J. D., Kimata K., Lindahl U. (2009) Proteoglycans and sulfated glycosaminoglycans in Essentials of Glycobiology (Varki A., Cummings R. D., Esko J. D., Freeze H. H., Stanley P., Bertozzi C. R., Hart G. W., Etzler M. E. eds), 2nd Ed., pp. 229–248, Cold Spring Harbor, New York: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Salmivirta M., Lidholt K., Lindahl U. (1996) Heparan sulfate: a piece of information. FASEB J. 10, 1270–1279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bernfield M., Götte M., Park P. W., Reizes O., Fitzgerald M. L., Lincecum J., Zako M. (1999) Functions of cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 68, 729–777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lander A. D. (1998) Proteoglycans: master regulators of molecular encounter? Matrix Biol. 17, 465–472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Park P. W., Reizes O., Bernfield M. (2000) Cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans: selective regulators of ligand-receptor encounters. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 29923–29926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Li J. P., Galvis M. L., Gong F., Zhang X., Zcharia E., Metzger S., Vlodavsky I., Kisilevsky R., Lindahl U. (2005) In vivo fragmentation of heparan sulfate by heparanase overexpression renders mice resistant to amyloid protein A amyloidosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 6473–6477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Vlodavsky I., Goldshmidt O., Zcharia E., Atzmon R., Rangini-Guatta Z., Elkin M., Peretz T., Friedmann Y. (2002) Mammalian heparanase: involvement in cancer metastasis, angiogenesis and normal development. Semin. Cancer Biol. 12, 121–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Escobar Galvis M. L., Jia J., Zhang X., Jastrebova N., Spillmann D., Gottfridsson E., van Kuppevelt T. H., Zcharia E., Vlodavsky I., Lindahl U., Li J. P. (2007) Transgenic or tumor-induced expression of heparanase upregulates sulfation of heparan sulfate. Nat. Chem. Biol. 3, 773–778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lord A., Kalimo H., Eckman C., Zhang X. Q., Lannfelt L., Nilsson L. N. (2006) The Arctic Alzheimer mutation facilitates early intraneuronal Aβ aggregation and senile plaque formation in transgenic mice. Neurobiol. Aging 27, 67–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Philipson O., Hammarström P., Nilsson K. P., Portelius E., Olofsson T., Ingelsson M., Hyman B. T., Blennow K., Lannfelt L., Kalimo H., Nilsson L. N. (2009) A highly insoluble state of Aβ similar to that of Alzheimer's disease brain is found in Arctic APP transgenic mice. Neurobiol. Aging 30, 1393–1405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mullan M., Crawford F., Axelman K., Houlden H., Lilius L., Winblad B., Lannfelt L. (1992) A pathogenic mutation for probable Alzheimer's disease in the APP gene at the N-terminus of β-amyloid. Nat. Genet. 1, 345–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Levy-Adam F., Miao H. Q., Heinrikson R. L., Vlodavsky I., Ilan N. (2003) Heterodimer formation is essential for heparanase enzymatic activity. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 308, 885–891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Englund H., Sehlin D., Johansson A. S., Nilsson L. N., Gellerfors P., Paulie S., Lannfelt L., Pettersson F. E. (2007) Sensitive ELISA detection of amyloid-β protofibrils in biological samples. J. Neurochem. 103, 334–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Knops J., Suomensaari S., Lee M., McConlogue L., Seubert P., Sinha S. (1995) Cell-type and amyloid precursor protein-type specific inhibition of A β release by bafilomycin A1, a selective inhibitor of vacuolar ATPases. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 2419–2422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zetser A., Levy-Adam F., Kaplan V., Gingis-Velitski S., Bashenko Y., Schubert S., Flugelman M. Y., Vlodavsky I., Ilan N. (2004) Processing and activation of latent heparanase occurs in lysosomes. J. Cell Sci. 117, 2249–2258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Meyer-Luehmann M., Spires-Jones T. L., Prada C., Garcia-Alloza M., de Calignon A., Rozkalne A., Koenigsknecht-Talboo J., Holtzman D. M., Bacskai B. J., Hyman B. T. (2008) Rapid appearance and local toxicity of amyloid-β plaques in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Nature 451, 720–724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Meyer-Luehmann M., Coomaraswamy J., Bolmont T., Kaeser S., Schaefer C., Kilger E., Neuenschwander A., Abramowski D., Frey P., Jaton A. L., Vigouret J. M., Paganetti P., Walsh D. M., Mathews P. M., Ghiso J., Staufenbiel M., Walker L. C., Jucker M. (2006) Exogenous induction of cerebral β-amyloidogenesis is governed by agent and host. Science 313, 1781–1784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wang L., Fuster M., Sriramarao P., Esko J. D. (2005) Endothelial heparan sulfate deficiency impairs l-selectin- and chemokine-mediated neutrophil trafficking during inflammatory responses. Nat. Immunol. 6, 902–910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Weller R. O., Subash M., Preston S. D., Mazanti I., Carare R. O. (2008) Perivascular drainage of amyloid-β peptides from the brain and its failure in cerebral amyloid angiopathy and Alzheimer's disease. Brain Pathol. 18, 253–266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]