Abstract

Diesel exhaust emissions contain numerous semivolatile organic compounds (SVOCs) for which emission information is limited, especially for idling conditions, new fuels and the new after-treatment systems. This study investigates exhaust emissions of particulate matter (PM), polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), nitro-PAHs (NPAHs), and sterane and hopane petroleum biomarkers from a heavy-duty (6.4 L) diesel engine at various loads (idle, 600 and 900 kPa BMEP), with three types of fuel (ultra-low sulfur diesel or ULSD, Swedish low aromatic diesel, and neat soybean biodiesel), and with and without a diesel oxidation catalyst (DOC) and diesel particulate filter (DPF). Swedish diesel and biodiesel reduced emissions of PM2.5, Σ15PAHs, Σ11NPAHs, Σ5Hopanes and Σ6Steranes, and biodiesel resulted in the larger reductions. However, idling emissions increased for benzo[k]fluoranthene (Swedish diesel), 5-nitroacenaphthene (biodiesel) and PM2.5 (biodiesel), a significant result given the attention to exposures from idling vehicles and the toxicity of high-molecular-weight PAHs and NPAHs. The DOC + DPF combination reduced PM2.5 and SVOC emissions during DPF loading (>99% reduction) and DPF regeneration (83–99%). The toxicity of diesel exhaust, in terms of the estimated carcinogenic risk, was greatly reduced using Swedish diesel, biodiesel fuels and the DOC + DPF. PAH profiles showed high abundances of three and four ring compounds as well as naphthalene; NPAH profiles were dominated by nitro-naphthalenes, 1-nitropyrene and 9-nitroanthracene. Both the emission rate and the composition of diesel exhaust depended strongly on fuel type, engine load and after-treatment system. The emissions data and chemical profiles presented are relevant to the development of emission inventories and exposure and risk assessments.

Keywords: Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), Nitro-PAHs (NPAHs), Hopanes, Steranes, Biodiesel, Diesel particulate filter (DPF)

1. Introduction

Vehicle exhaust emissions are one of the most important anthropogenic sources of air pollutants, and standards and regulations to reduce emissions of particulate matter (PM), carbon monoxide (CO), nitrogen oxides (NOx), and nonmethane hydrocarbon (NMHC) emissions have been widely applied (Karavalakis et al., 2010; Khalek et al., 2011). Exhaust emissions include many other pollutants of health concern, including semivolatile organic compounds (SVOCs) such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) (Simcik et al., 1999; Li et al., 2003). Despite the toxicity of many compounds, SVOCs are not directly regulated except as part of PM mass or number concentration standards. Exhaust emissions depend on many factors, e.g., fuel type and quality, engine type, after-treatment technologies, engine operating (driving) conditions, and engine wear and maintenance (Karavalakis et al., 2010).

SVOCs in vehicle exhaust are found in both solid and vapor forms and, besides PAHs, include nitro-PAHs (NPAHs), hopanes, steranes, and numerous other compound classes (Khalek et al., 2011). PAHs can be emitted as unburned fuels and lubricating oils, or formed during combustion from other organic compounds (Karavalakis et al., 2010). NPAHs can be formed by reactions of PAHs with hydroxyl (OH) and nitrate (NO3) radicals in the presence of NOx, and through nitration during the combustion process (Karavalakis et al., 2010). Oils, fuels and after-treatment controls affect emissions, as summarized below.

Ultra-low sulfur conventional diesel (ULSD, sulfur content <15 ppm) has fueled most on-road diesel vehicles in the U.S. since 2006 (EPA, 2012). In the past decade, the consumption of biodiesel and other alternative fuels has burgeoned, and soy-based biodiesels are now widely available. In Sweden, low sulfur (2–5 ppm) and low aromatic (<5% volume) diesel is used (Westerholm et al., 2001). Such fuels, either neat or in blends with conventional diesel, can reduce emissions PM, CO and NMHC emissions (Ratcliff et al., 2010; Chin et al., 2012). While biodiesel and low-aromatic fuels are expected to decrease PAH and NPAH emissions due to the lower content of key PAH precursors (Karavalakis et al., 2010; Ratcliff et al., 2010), information regarding these (and other unregulated) emissions with alternative fuels is limited and inconsistent. As examples: soybean-based biodiesel and biodiesel blends substantially reduced particle-associated PAH and NPAH emissions compared to reference diesel (Bagley et al., 1998; Westerholm et al., 2001; Correa and Arbilla, 2006; Karavalakis et al., 2010; Ratcliff et al., 2010); emissions increased or were unchanged with canola oil-based biodiesel (Zou and Atkinson, 2003); and while PAH emissions were reduced, NPAH and oxy-PAH emissions increased with soy-based biodiesel (Karavalakis et al., 2010).

Engine exhaust emissions also include hopanes and steranes, compounds derived largely from the lipid fraction of once-living organisms (Peters et al., 2007) that mainly originate from engine lubricating oil (Schauer et al., 1999, 2002; Kleeman et al., 2008). Considered petroleum biomarkers, hopane and sterane measurements have been used to help apportion sources of ambient PM (Huang et al., 2006; Kleeman et al., 2009). A few studies indicate that hopane and sterane emission rates were not affected by alternative fuels such as biodiesel (Cheung et al., 2010; Magara-Gomez et al., 2012).

After-treatment technologies strongly affect emissions. Diesel particulate filters (DPF), used in conjunction with ULSD, significantly reduce PM emissions (EPA, 2013) and PM-associated PAH emissions (Heeb et al., 2008, 2010; Ratcliff et al., 2010). Effects reported for NPAHs, however, are inconsistent. For example, Ratcliff et al. measured >90% conversion of most NPAHs and 35% reduction of 1-nitropyrene (Ratcliff et al., 2010), while Heeb et al. found emissions of some NPAHs increased, possibly due to secondary nitration reactions in the DPF (Heeb et al., 2008, 2010). These studies did not measure 6-nitrochrysene, which has a high carcinogenic potency (RIDEM, 2008). Additional information is needed to elucidate effects of DPFs on NPAH emissions, as well as on hopane and sterane emissions for which no information is available.

This study investigates exhaust emissions of PAHs, NPAHs, hopanes and steranes using well-controlled bench tests of a heavy-duty diesel engine. Emissions are tested at idle and two loaded conditions with three types of fuels, and with and without a DOC + DPF. The results help elucidate effects of alternative fuels, engine load, and control technology on emissions of toxic pollutants and petroleum marker compounds.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Engine, fuels and test conditions

The test engine is a Ford 2008 6.4 L “Power Stroke” engine manufactured by Navistar International Corporation (Lisle, IL) used in pick-up trucks, SUVs, vans, and school buses. This 8 cylinder, 32 valve common rail direct-injection engine is equipped with dual sequential turbocharging, cooled exhaust gas recirculation (EGR), and an EGR oxidation catalyst. Bore, stroke and compression ratio are 98.0 mm, 104.9 mm, and 16.7:1, respectively. Maximum power and torque are 261 kW at 3000 rpm and 880 Nm at 2000 rpm.

Three fuels tested were mid-cetane U.S. specification ultralow sulfur conventional diesel (sulfur content <15 ppm), Swedish Environmental Class 1 (MK1) low sulfur and low aromatic diesel fuel (Swedish, sulfur content <10 ppm, aromatics <5% volume) (Haltermann Ltd., Hamburg, Germany), and neat soy-based bio-diesel (B100, 100% soy methyl ester) (Peter Cremer North America, Cincinnati, OH, USA). Fuel properties are listed in Table 1. ULSD and Swedish fuel properties were measured by Paragon Laboratories (Livonia, MI, USA), and biodiesel by Peter Cremer North America. Conventional petroleum lubricating oil was used (Shell Rotella-T 15W-40).

Table 1.

Properties of ULSD, Swedish diesel and B100.

| Fuel parameters | ULSD | Swedish | Biodiesel | Test method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Product name | Amoco Ultra Low Sulfur#2 Premium Diesel Fuel | Halterman HF0860 Swedish Environmental Class I Diesel Fuel | Peter Cremer Nexol BD-99.9 Biodiesel | |

| Cetane number | 46.7 | 55.9 | 55 | ASTM D613 |

| Kinematic viscosity (mm2/s at 40 °C | 2.3 | 1.843 | 4.0 | ASTM D445 |

| Net heating value (MJ/kg) | 42.699 | 43.535 | 37.348 | ASTM D240 |

| Carbon (wt%) | 86.69 | 85.72 | 77.27 | ASTM D5281 |

| Hydrogen (wt%) | 13.31 | 14.28 | 11.82 | ASTM D5281 |

| Oxygen (wt %) | <0.05 | <0.05 | 10.91 | ASTM D5622 |

| Sulfur content (wt ppm) | <15 | <10 | <1 | ASTM D5453, D7039 |

| C/H atomic ratio | 1.829 | 1.985 | 1.823 | ASTM D5281 |

| Saturates/Olefins/Aromatics (vol%) | 59.2/4.5/36.3 | 95.4/1.3/3.3 | N/A | ASTM D1319 |

The test configuration approximates a 2004 engine calibration without exhaust gas after-treatment (Table 2). For tests with after-treatment, the engine was equipped with a 2008 Ford F250 production DOC (cordierite substrate) and catalyzed DPF system (silicon carbide substrate, 31 cells/cm2 (200 cpsi), wall thickness of 0.457 mm (18 MIL), 42% porosity, 11 ± 2 μm pore size). Experiments used 11 test conditions described in Table 2. Tests 1–9 operated the engine without after-treatment using each fuel at idle, low-load (600 kPa BMEP at 1500 rpm), and high-load (900 kPa BMEP at 2500 rpm). Injection timing was set as at 3.5° after top dead center (ATDC). Test 10 sampled tailpipe PM during DPF loading, and test 11 sampled tailpipe PM during DPF regeneration. DPF regeneration used four injections, including two very late injections that elevated engine-out hydrocarbon concentration to boost the temperature rise across the DOC. Except for condition 11, each test was run in triplicate, and three filter samples were collected sequentially.

Table 2.

Experimental design and test conditions.

| Test | Engine | Fuel | Calibration | BMEP (kPa) | Speed (rpm) | After-treatment | No. of samples | Power (kW) | EGR (%) | Start of injection (degree ATDC)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 6.4 L Ford | ULSD | 2004 | 600 | 1500 | None | 3 | 48.2 | 14 | 3.5 |

| 2 | 900 | 2500 | None | 3 | 120.3 | 17 | 3.5 | |||

| 3 | Idle | 650 | None | 3 | 0.1 | 8 | 3.5 | |||

| 4 | Swedish | 600 | 1500 | None | 3 | 48.1 | 14 | 3.5 | ||

| 5 | 900 | 2500 | None | 3 | 121 | 17 | 3.5 | |||

| 6 | Idle | 650 | None | 3 | 0.2 | 8 | 3.5 | |||

| 7 | B100 | 600 | 1500 | None | 3 | 47.8 | 14 | 3.5 | ||

| 8 | 900 | 2500 | None | 3 | 120.2 | 17 | 3.5 | |||

| 9 | Idle | 650 | None | 3 | 0.1 | 8 | 3.5 | |||

| 10 | ULSD | 600 | 1500 | DOC + DPF | 3 | 48.4 | 14 | −12/−3 | ||

| 11 | 500 | 1500 | DOC + DPF regen | 1 | 40.3 | 0 | 1/9/47/139 |

ATDC: after top dead center. A negative number means degrees before top dead center (BTDC).

2.2. Exhaust measurements

A heated AVL 415S smoke meter and heated sample line (AVL Inc., Plymouth, MI, USA) measured filter smoke number (FSN), which was converted to mass of carbonaceous soot using a correlation proposed by Christian et al. (Christian et al., 1993) that also applies to low smoke levels and biodiesel (Northrop et al., 2011). The soluble organic fraction (SOF) was calculated as the difference between PM (described below) and carbonaceous soot, normalized by PM.

Exhaust PM was sampled using a partial flow dilution tunnel (BG-2, Sierra Instruments Inc., Monterey, CA, USA) at a flow rate of 10 L/min through a heated (191 °C) stainless steel sample probe (0.95-cm dia., 40-cm length) inserted into the center of a straight section of exhaust pipe, facing upstream, and 2 m downstream of the engine’s turbine (Supplemental Fig. S1). The dilution tunnel, at the probe’s end, mixed raw exhaust with filtered air (dilution ratio = 6:1). The mixture then passed through a transfer tube (16 mm dia., 40 cm length) to a 2.5-μm cyclone separator (Sierra Instruments Inc., Monterey, CA, USA), a second transfer tube (16 mm i.d., 20 cm length), and to a Teflon filter cassette holder (Sierra Instruments Inc., Monterey, CA, USA) supporting a 47 mm PTFE-bonded glass fiber filter (Emfab™ TX40-HI20WW; Pall Corporation, Port Washington, NY, USA) on a perforated stainless steel backing plate. The exposed area of the filter was 39 mm in diameter. The transfer tubes, cyclone separator, and filter were maintained at 47 ± 5 °C, and the filter flow rate was 60 L/min (face velocity = 91 cm/s).

Before sampling, flows were stabilized for 60 s, and additional dilution air was back flushed into the exhaust pipe. Sampling times were adjusted to load filters with >280 μg of PM, at which point the pressure drop across the filter reached ~30 kPa. After sampling, the filter and cassette were immediately wrapped with Parafilm, placed in a sealed metal container, and transported to the laboratory for filter conditioning and weighing. A 30-s high-flow purge cycle (100 L/min) was used to minimize PM accumulation in the dilution tunnel and the transfer line prior to the next sample.

Filters were weighed before and after PM loading after conditioning for 24 h in a glove box (Series 100 twin plastic glove box isolator, Terra Universal, Inc.) held at 25 °C and 33% relative humidity (RH). Electrostatic charges on filters and instruments were neutralized using an ionizer (Terra Universal, Inc.) for 30 min before weighing. Filters were weighed twice to 1 μg using a microbalance (ME 5, Sartorius Inc., Edgewood, NY, USA). If weights were within 5 μg, results were averaged; otherwise filters were reweighed.

To the extent possible, the PM sampling and analysis protocols were consistent with the EPA testing procedures (CFR, 2013), ISO-DIS 16183 (ISO 2009), verbal recommendations by Sierra Instruments, and internal standard operating protocols. To quantify the overall reproducibility (including engine, dilution tunnel, and filter conditioning, and filter weighing), nine PM samples were collected at specified conditions over a 2-day period. These tests showed good repeatability, i.e., the 95% confidence interval was ± 5.1% of the collected PM mass.

2.3. Materials

All solvents were HPLC grade and obtained from Fisher Scientific Inc. (Pittsburgh, PA, USA). Florisil (60–100 mesh) and sodium sulfate (anhydrous, certified ACS granular, 10–60 mesh) for column chromatography were supplied by the same vendor. Target compounds included 16 PAHs, 11 NPAHs, 5 hopanes and 6 steranes (Table 3). Authentic standards were purchased from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories (CIL, Andover, MA), Sigma–Aldrich (St. Louis, MO), and Chiron Laboratories (Trondheim, Norway). Surrogate standards included C27-α,α,α-(20R)-cholestane-d2, 1-nitropyrene-d9, chrysene-d12 and naphthalene-d8 (Chiron Laboratories, Trondheim, Norway). Internal standards (IS) for PAH analyses were fluoranthene-d10 (CIL) and an IS PAH mixture (Wellington Laboratories, Guelph, ON, Canada). The IS for NPAHs was 1-nitrofluoanthene-d9 (CIL), and n-tetracosane-d50 (Chiron) for hopanes and steranes.

Table 3.

List of target compounds.

| Group | Compound | Abbrev. | CAS# | MW g/mol | # of rings | IDL (ng/mL) | TEF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAHs | Naphthalene | NAP | 91-20-3 | 128.17 | 2 | 0.50 | 0.001a |

| Acenaphthylene | ACY | 208-96-8 | 152.19 | 3 | 0.25 | 0.001a | |

| Acenaphthene | ACT | 83-32-9 | 154.21 | 3 | 0.22 | 0.001a | |

| Phenanthrene | PHE | 85-01-8 | 178.23 | 3 | 0.22 | 0b | |

| Anthracene | ANT | 120-12-7 | 178.23 | 3 | 0.18 | 0b | |

| Fluoranthene | FLA | 206-44-0 | 202.25 | 4 | 0.32 | 0.08b | |

| Pyrene | PYR | 129-00-0 | 202.25 | 4 | 0.25 | 0b | |

| Benzo[a]anthracene | BAA | 56-55-3 | 228.29 | 4 | 0.25 | 0.20b | |

| Chrysene | CHR | 218-01-9 | 228.29 | 4 | 0.28 | 0.10b | |

| Benzo[b]fluoranthene | BBF | 205-99-2 | 252.31 | 5 | 0.08 | 0.80b | |

| Benzo[k]fluoranthene | BKF | 207-08-9 | 252.31 | 5 | 0.05 | 0.03b | |

| Benzo[a]pyrene | BAP | 50-32-8 | 252.31 | 5 | 0.05 | 1.00b | |

| Dibenzo[a,h]anthracene | DBA | 53-70-3 | 278.35 | 5 | 0.09 | 10.00b | |

| Indeno[1,2,3-cd] pyrene | IND | 193-39-5 | 276.33 | 6 | 0.12 | 0.07b | |

| NPAHs | 1-Nitronaphthalene | 1-NNAP | 86-57-7 | 173.17 | 2 | 0.01 | n/ac |

| 2-Nitronaphthalene | 2-NNAP | 581-89-5 | 173.17 | 2 | 0.01 | n/ac | |

| 2-Nitrobiphenyl | 2-NBPL | 86-00-0 | 199.21 | 2 | 0.01 | n/ac | |

| 3-Nitrobiphenyl | 3-NBPL | 2113-58-8 | 199.21 | 2 | 0.01 | n/ac | |

| 4-Nitrobiphenyl | 4-NBPL | 92-93-3 | 199.21 | 2 | 0.01 | n/ac | |

| 5-Nitroacenaphthene | 5-NACT | 602-87-9 | 199.21 | 3 | 0.01 | 0.03d | |

| 2-Nitrofkuorene | 2-NFLU | 607-57-8 | 211.22 | 3 | 0.01 | 0.01d | |

| 9-Nitroanthracene | 9-NANT | 602-60-8 | 223.23 | 3 | 0.01 | n/ac | |

| 9-Nitrophenanthrene | 9-NPHE | 954-46-1 | 223.23 | 3 | 0.01 | n/ac | |

| 1-Nitropyrene | 1-NPYR | 5522-43-0 | 247.25 | 4 | 0.01 | 0.1d | |

| 6-Nitrochrysene | 6-NCHR | 7496-02-8 | 273.29 | 4 | 0.01 | 10d | |

| Hopanes | 17α(H),21β(H)-Hopane | Hop1 | 471-62-5 | 412.73 | 5 | 0.05 | |

| 17α(H)-22,29,30-Trisnorhopane | Hop2 | 53584-59-1 | 370.65 | 5 | 0.08 | ||

| 17a(H),21β(H)-30-Norhopane | Hop3 | 53584-60-4 | 398.71 | 5 | 0.08 | n/ac | |

| 22R-17α(H),21β(H)-Homohopane | Hop4 | 60305-22-8 | 426.76 | 5 | 0.05 | ||

| 22S-17α(h),2β(h)-Homohopane | Hop5 | 60305-23-9 | 426.76 | 5 | 0.05 | ||

| Steranes | 20S-5α(H), 14α(H), 17α(H)-Cholestane | Ste1 | 41083-75-4 | 372.67 | 4 | 0.04 | |

| 20R-5α(H), 14α(H), 17α(H)-Cholestane | Ste2 | 481-21-0 | 372.67 | 4 | 0.06 | ||

| 20R-5α(H), 14β(H), 17β(H)-Cholestane | Ste3 | 69483-47-2 | 372.67 | 4 | 0.04 | n/ac | |

| 20R-5α(H), 14β(H), 17β(H)-24-Methylcholestar | Ste4 | 71117-90-3 | 386.7 | 4 | 0.06 | ||

| 20R-5α(H), 14α(H), 17a(H)-24-Ethylcholestane | Ste5 | 62446-14-4 | 400.72 | 4 | 0.05 | ||

| 20R-5α(H), 14β(H), 17β(H)-24-Ethylcholestane | Ste6 | 71117-92-5 | 400.72 | 4 | 0.06 |

IDL: instrumental detection limit. TEF: toxic equivalency factor. CAS #: Chemical Abstracts Service Registry Number. MW: molecular weight.

No information available.

Based on California cancer potency factors, cited in Rhode Island Air Toxics Guideline Table F (RIDEM, 2008).

2.4. SVOC analysis

Filters were extracted by placing each in a 50 mL centrifuge tube, adding 15 μL of the surrogate standard, adding 25 mL of dichloromethane/hexane (4:1, v/v) immersing the entire filter, and sonicating for 30 min (1510R-MTH, Branson Ultrasonics Corporation, Danbury, CT). The filter was then removed using a cotton stick and discarded. Extracts were passed through an activated Florisil column and fractionated into three portions: fraction A was eluted with 15 mL of hexane; fraction B with 15 mL of hexane/acetone (1:1, v/v); and fraction C with 30 mL of methanol. Each fraction was evaporated under nitrogen gas to 0.25 mL. Fractions A, B and C were analyzed for hopanes and steranes, PAHs, and NPAHs, respectively. No additional cleaning of each fraction was necessary.15 μL of the IS was added to extracts using a 25 μL syringe prior to analysis.

Target compounds were measured using a gas chromatography-mass spectrometer (GC-MS; HP 6890/5973, Agilent Industries, Palo Alto, CA, USA), splitless 2 μL injections, and a capillary column (DB-5: 30 m × 0.25 mm id; film thickness 0.25 μm; J&W Scientific, Folsom, CA, USA). Injector and detector temperatures were 275 °C and 280 °C, respectively. Temperature programs have been described previously (Huang et al., 2013). The carrier gas was helium (flow of 1.5 mL/min, pressure of 37.4 kPa, average velocity of 31 cm/s), and the reagent gas for the MS detector, operated in the negative chemical ionization (NCI) mode for NPAHs, was ultra high purity methane. The MS detector was operated in the electron impact (EI) mode for PAHs, hopanes and steranes. Each compound was quantified against authentic standards (described above).

Quality assurance (QA) measures included the use of field and sample blanks, and surrogate spike recovery tests. Several targets were detected at trace levels (well below sample levels) in blanks. Spike recoveries averaged 89%, 85% and 91% for PAHs, NPAHs and biomarkers, respectively. Data were not corrected for spike recoveries or blanks. Shifts (abundance of target compounds in standard solutions before and after running a batch of samples) were below the 25% limit. QA data including blanks and surrogate spike recoveries are presented in Supplemental Tables S1–S4. Instrumental detection limits (IDLs) are presented in Table 3.

2.5. Data analysis

PM mass (μg) was calculated as the difference in filter weights before and after loading. Emissions were expressed as brake-specific emissions (e.g., g/kWh or μg/kWh) for loaded conditions, and as emission rates per time (e.g., mg/s or ng/s) for idle conditions (since BMEP was near zero). Comparisons between idle and loaded conditions used emission rates per time. Reference or baseline emissions refer to emissions using ULSD and without the DPF. Baseline emissions were compared to literature data using both ULSD and older fuels. For each test except #11, SVOC measurements were averaged over three replicate filters, and differences between ULSD and Swedish fuels, between ULSD and B100 fuels, and with and without after-treatment and DPF, were evaluated using 2-sample t tests (2-tailed, significance level p = 0.05).

To evaluate the carcinogenic potential of engine exhaust, the toxic equivalency of benzo[a]pyrene (B[a]P, TEQB[a]P) was calculated by weighting each PAH or NPAH by its potency (toxic equivalent, TEQ) to that of B[a]P, which was given a weight of one, and determining the overall toxicity as TEQB[a]P = Σi Ci TEFi, where Ci = emission rate of the ith PAH or NPAH in the sample (ng/kWh) (Schoeny and Poirier, 1993). TEQs are shown in Table 3. While used for many years to characterize the toxicity of mixtures, the TEQ approach does not reflect other important health endpoints in air pollution, e.g., oxidative stress and immune response.

PAH and NPAH profiles were developed to represent on-road diesel sources for possible use in receptor models that apportion emission sources based on the chemical composition of emissions. The profiles used emission rates (ng/s) for ULSD and weighted idle, low- and high-load results by 24, 21 and 55%, respectively, reflecting activity data for medium and heavy duty diesel trucks (Lutsey et al., 2004; Huai et al., 2006). A composite PM2.5 emission rate (ng/s) was also calculated using the same approach. PAH and NPAH profiles were expressed as abundances, i.e., each compound’s abundance is its fraction of total PAH emissions (ΣPAHs) or total NPAH emissions (ΣNPAHs). Profiles were plotted and compared to those in the literature, derived similarly, using Spearman correlation coefficients. These and other statistical analyses used SPSS Statistics 21.0 (IBM Corporation).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Baseline emissions

Using ULSD, PM emissions under low- and high-load conditions were 0.033 ± 0.001 and 0.10 ± 0.002 g/kWh, respectively, comparable to measurements reported in other studies, most of which ranged from 0.03 to 0.3 g/kWh (Tanaka et al., 1998; Sharp et al., 2000a; Gambino et al., 2001; Hori and Narusawa, 2001; Lea-Langton et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2010; Ratcliff et al., 2010). For ΣPAHs, emissions at low load were slightly below earlier reports (Sharp et al., 2000b; Liu et al., 2010; Khalek et al., 2011), but emissions at high load (3.3 μg/kWh) were similar to a previous study (2.21 μg/kWh) (Sharp et al., 2000b). ΣNPAH emission rates (0.2 μg/kWh at high load) were similar to those in two previous studies (Sharp et al., 2000b; Gambino et al., 2001). ΣHopane and ΣSterane emission rates under high load (0.02 and 1 μg/kWh, respectively) were slightly lower than earlier reports (Liu et al., 2010; Khalek et al., 2011). For most SVOCs, emission rates increased greatly under load, e.g., ΣPAH emissions increased 6-fold from low to high load (0.55–3.3 μg/kWh); ΣNPAH emissions increased 4-fold (0.05–0.2 μg/kWh).

3.2. Effect of fuel and engine load

3.2.1. PM emissions, soot emissions and SOF

PM2.5 emission rates strongly depended on fuel and engine load. Under load, Swedish diesel reduced PM2.5 emissions by 7–27% compared to ULSD, and B100 reduced emissions by 68–81% (Table 4). However, while idling, PM2.5 emission rate with B100 (0.60 ± 0.06 mg/s) was 5.5 times higher than with ULSD (0.11 ± 0.01 mg/s). Like PM2.5, emissions of carbonaceous soot were reduced using Swedish diesel and B100 under the three conditions (Table 4). Notably, B100 increased PM2.5 emissions during idling, but at the same time, reduced soot emissions. PM2.5 and soot emission rates were highest under high load, and decreased at low load and still further at idle, with the exception of PM2.5 using B100 at idle (0.60 ± 0.06 mg/s), where almost the same emission rate was found as at high load (0.65 ± 0.06 mg/s) (Table 4).

Table 4.

PM and carbonaceous soot emission rates using different fuels. Change (%) is the percent change compared to ULSD for the same engine condition.

| Engine condition | Fuel | PM

|

Soot

|

SOF

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (mg/s) | Change (%) | (mg/s) | Change (%) | (Unitless) | Change (%) | ||

| Idle | ULSD | 0.11 ± 0.01 | 0.009 ± 0.003 | 0.92 ± 0.04 | |||

| Swedish | 0.02 ± 0.00a | −82 | 0.003 ± 0.000a | −67 | 0.85 ± 0.02a | −8 | |

| B100 | 0.60 ± 0.06a | 445 | 0.003 ± 0.000a | −67 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 9 | |

| Low-load | ULSD | 0.44 ± 0.02 | 0.25 ± 0.02 | 0.43 ± 0.02 | |||

| Swedish | 0.41 ± 0.07 | −7 | 0.27 ± 0.00 | 8 | 0.33 ± 0.12 | −23 | |

| B100 | 0.14 ± 0.01a | −68 | 0.022 ± 0.001a | −91 | 0.84 ± 0.01a | 95 | |

| High-load | ULSD | 3.42 ± 0.08 | 2.9 ± 0.1 | 0.15 ± 0.04 | |||

| Swedish | 2.48 ± 0.03a | −27 | 1.9 ± 0.1a | −34 | 0.21 ± 0.03 | 40 | |

| B100 | 0.65 ± 0.06a | −81 | 0.14 ± 0.01a | −95 | 0.78 ± 0.00* | 420 | |

SOF: soluble organic fraction. SOF + (PM − soot)/PM.

Differed significantly from ULSD under the same engine condition (p < 0.05 using two-sample t-test).

A number of studies have found that biodiesel reduces PM2.5 and soot emission rates as compared to ULSD (Sharp et al., 2000a; EPA, 2001; Lapuerta et al., 2008; Chin et al., 2012). This has been attributable to the lower content of aromatic hydrocarbons and sulfur in biodiesel and biodiesel blends that serves as soot precursors (Sharp et al., 2000a; Lapuerta et al., 2008). Biodiesel’s higher oxygen content also may lead to more complete combustion and the oxidation of already formed soot, further reducing emissions (Sharp et al., 2000a; Lapuerta et al., 2008). Swedish diesel has been reported to reduce PM emissions by 11% compared to an European reference diesel (similar to ULSD) (Westerholm et al., 2001), again probably reflecting the lower sulfur as well as lower aromatic content of Swedish diesel. However, we found that B100 dramatically increased PM2.5 emissions while idling. A similar increase was observed using B20 in a light-duty engine (Chin et al., 2012). Under idle conditions, exhaust gas temperatures are low (<150 °C), and unburned fuel and oil may represent a significant fraction of PM2.5 emissions, potentially exceeding the reduction in soot and sulfate emissions (Sharp et al., 2000a). PM emissions at idle may even be underestimated given the low exhaust temperatures (<150 °C), which could increase the collection of volatiles on exhaust pipe surfaces.

The SOF of PM emissions increased using biodiesel for each of the three conditions tested, but decreased with increasing engine load with the same fuel (Table 4). Many factors can affect emissions. Biodiesel’s higher viscosity and lower vapor pressure may decrease fuel–air mixing and fuel vaporization, potentially increasing the SOF, the unburned hydrocarbon emissions present in PM. However, the SOF may be reduced by biodiesel’s higher oxygen content, which can promote combustion, and by biodiesel’s lower soot emissions, which reduces the surface area available for adsorption of volatiles. The net effect for conditions in this study was increased SOF with biodiesel, a result found in other studies using biodiesel-ULSD blends (Di et al., 2009; Zhang and Balasubramanian, 2014).

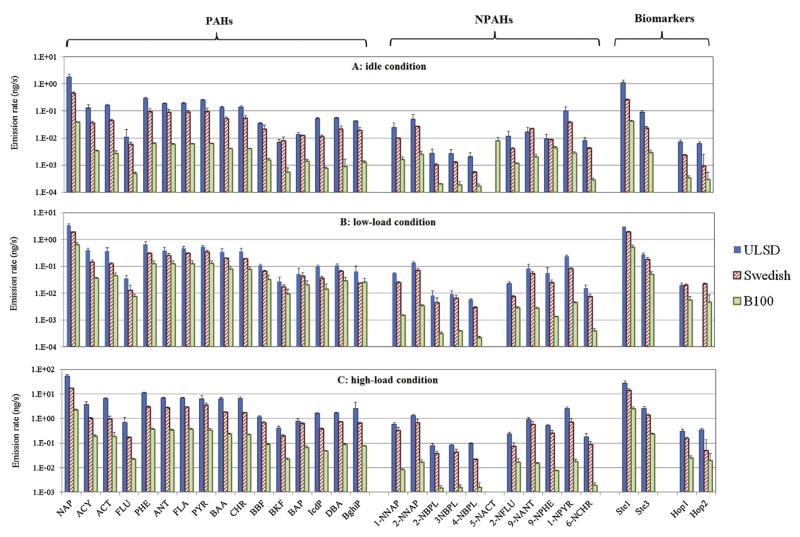

3.2.2. PAH emissions

The highest Σ15PAH emission rates were obtained under high-load conditions when all 15 target PAHs were detected (Fig. 1). Emissions of Σ15PAH increased with load: compared to idling, low-load conditions increased Σ15PAH emissions by 2–18 fold, while high-load conditions increased emissions by 32–58 fold (Table 5). Compared to ULSD, Swedish diesel reduced Σ15PAH emissions by 45–68% and B100 by 79–98%; these reductions were statistically significant (Table 5). Individual compounds followed the same trend as Σ15PAHs with the exception that Swedish diesel slightly increased benzo[k]fluoranthene emissions while idling. The lower emission rates for PAHs are consistent with the low aromatic content in the Swedish fuel and the absence of aromatics in bio-diesel (Westerholm et al., 2001; Karavalakis et al., 2010; Ratcliff et al., 2010).

Fig. 1.

Effect of fuel on speciated SVOC emission rates (ng/s) for (A) idling, (B) low-load, and (C) high-load conditions. Error bars show one standard deviation. Compounds with missing values were below IDLs.

Table 5.

SVOC emission rates and TEQs using different fuels. Change (%) is the percent change compared to ULSD for the same engine condition.

| Engine condition | Fuel | Σ15PAH

|

Σ11NPAH

|

Σ5Hopane

|

Σ6Sterane

|

TEQBAP

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (ng/s) | Change (%) | (ng/s) | Change (%) | (ng/s) | Change (%) | (ng/s) | Change (%) | (ng/s) | Change (%) | ||

| Idle | ULSD | 3.4 ± 0.5 | 0.23 ± 0.08 | 0.013 ± 0.002 | 1.21 ± 0.24 | 0.75 ± 0.04 | |||||

| Swedish | 1.1 ± 0.2a | −68 | 0.116 ± 0.004 | −50 | 0.006 ± 0.001a | −54 | 0.279 ± 0.025a | −77 | 0.31 ± 0.09a | −59 | |

| B100 | 0.082 ± 0.002a | −98 | 0.023 ± 0.004a | −90 | 0.001 ± 0.000a | −92 | 0.045 ± 0.003a | −96 | 0.017 ± 0.007a | −98 | |

| Low-load | ULSD | 7.3 ± 1.5 | 0.63 ± 0.12 | 0.037 ± 0.002 | 3.25 ± 0.10 | 1.6 ± 0.2 | |||||

| Swedish | 4.0 ± 0.2a | −45 | 0.28 ± 0.05a | −56 | 0.046 ± 0.004a | 24 | 2.09 ± 0.21a | −36 | 0.93 ± 0.05a | −42 | |

| B100 | 1.5 ± 0.3a | −79 | 0.016 ± 0.001a | −97 | 0.013 ± 0.003a | −65 | 0.570 ± 0.110a | −82 | 0.37 ± 0.12a | −77 | |

| High-load | ULSD | 110 ± 11 | 6.6 ± 0.9 | 0.657 ± 0.096 | 30.1 ± 7.5 | 23 ± 1 | |||||

| Swedish | 37 ± 2a | −66 | 2.8 ± 1.0a | −58 | 0.323 ± 0.027a | −51 | 15.5 ± 2.7a | −49 | 10.2 ± 0.3a | −56 | |

| B100 | 4.8 ± 0.4a | −96 | 0.08 ± 0.01a | −99 | 0.057 ± 0.014a | −91 | 2.74 ± 0.43a | −91 | 1.11 ± 0.09a | −95 | |

ND: not detected.

Differed significantly from ULSD under the same engine condition (p < 0.05 using two-sample t-test).

Σ15PAH emission rates were positively correlated with PM2.5 emission rates (r = 0.93, p < 0.001), but negatively correlated with SOF (r = −0.70, p < 0.001), expected since biodiesel and Swedish diesel reduced Σ15PAH emissions but increased SOF. Also, increased engine load was accompanied with greater Σ15PAH emissions (Table 5) but lower SOF (Table 4). Both biodiesel and Swedish diesel appeared to increase emissions of unburned fuel and oil in PM, which contributed to SOF emissions although these fuels contain few or no aromatics. Similarly, low load and idle conditions may increase the fraction of unburned fuel and oil, leading to high SOF but low PAH emission rates.

3.2.3. NPAH emissions

Emission rates of total and speciated NPAHs are summarized in Table 5 and Fig. 1, respectively. All 11 target NPAHs were detected above MDLs while idling, and 10 were found at low- and high-load conditions. The most abundant compound was 1-nitropyrene, followed by 2-nitronaphthalene and 1-nitronaphthalene. Like PAHs, Σ11NPAH emissions generally increased with load, e.g., compared to idling, Σ11NPAH emissions increased by 2-fold at low load (except for B100), and by 4–28-fold at high load (Table 5). Compared to ULSD, Swedish diesel reduced Σ11NPAH emissions by 50–58%, and B100 reduced emissions by 90–99%. These large changes were statistically significant (Table 5). Individual compounds followed the same trend as Σ11NPAHs, but B100 generated highest emissions of 5-nitroacenaphthene during idling.

NPAH emission data in the literature are limited. Using a D12A 420 diesel engine (6-cylinder, heavy-duty), Swedish diesel reduced 1-nitropyrene emissions (particulate and vapor) compared to a reference fuel (Westerholm et al., 2001), similar to our observations. Like Σ15PAH, Σ11NPAH emission rates were positively correlated with PM2.5 emission rates (r = 0.94, p < 0.001) and negatively correlated with SOF (r = −0.72, p < 0.001).

5-Nitroacenaphthene was detected only with B100 during idling. NPAH emissions increased during idling for a Euro 2 compliant VW Golf 1.9 TDi diesel engine with B100 following a low speed driving cycle (Karavalakis et al., 2010). Biodiesel generally increased emissions of NOx (EPA, 2001; Chin et al., 2012) and the SOF of PM, which consisted of unburned fuel and oil (Sharp et al., 2000a; Karavalakis et al., 2010). At low temperature idle conditions, biodiesel appears to lead to poorer combustion that facilitates the formation of products of incomplete combustion (PICs) including PAHs, which then may react with hydroxyl (OH) and nitrate (NO3) radicals in the presence of NOx to form NPAHs, thus promoting emissions of some NPAHs.

During sample collection, NOx can react with PAHs collected on filters to form NPAHs (Stenberg et al., 1983; Hartung et al., 1984; Coutant et al., 1988; Schauer et al., 2003). However, formation of such artifacts was minor under the conditions of the Federal Test Procedure (Lies et al., 1985; Matti Maricq, 2007), and artifacts represented below 30% of 1-nitropyrene in heavy-duty diesel engine exhaust sampled for up to 41-min (Schuetzle and Perez, 1983). While not estimated in the present study, artifact formation seems unlikely to alter our main results. In particular, we found very large differences in NPAH emissions among fuels (e.g., 2–3-fold differences between ULSD and Swedish diesel, and 10–100-fold differences between ULSD and B100). Even if formation was significant, then the higher NOx emissions with biodiesel might have increased NPAH artifact formation, in which case the true NPAH emission rate with B100 would have been even lower, supporting our finding that B100 significantly lowered NPAH emissions.

3.2.4. Hopane and sterane emissions

Emission rates of total and speciated hopanes and steranes are summarized in Table 5 and Fig. 1. Only two hopanes and two steranes were detected above IDLs. Swedish diesel reduced Σ5Hopane emissions by 51–54% compared to ULSD under idling and high load, but emissions increased by 24% at low load. The Swedish fuel reduced Σ6Sterane emissions under all three conditions by 36–77%. B100 reduced emissions of both Σ5Hopane (by 65–92%) and Σ6Sterane (by 82–96%). As seen with the PAHs and NPAHs, hopane and sterane emissions increased with engine load, and emission rates of individual compounds followed the trend of the totals.

Hopanes and steranes have been used as tracers of diesel and gasoline vehicles in studies apportioning sources of ambient PM (Kleeman et al., 2008, 2009). These markers have been detected in vehicle exhaust but not in diesel/gasoline fuels (Schauer et al., 1999, 2002). It has been suggested that these compounds are found in the higher temperature fraction of crude oils, and thus are only found in lubricating oils (Rogge et al., 1993). While two studies found that biodiesel did not affect hopane and sterane emission rates compared to conventional diesel (Cheung et al., 2010; Magara-Gomez et al., 2012), our results show significant effects of fuel type. We speculate that fuel type may affect the amount of lubricating oil released into exhaust through several mechanisms. First, with a constant injection time, the higher cetane number of B100 and Swedish diesel results in earlier combustion, which causes fuel to burn closer to the injector and decreases the oil washed from the cylinder walls by the fuel spray. Second, higher cetane number fuels may lead to less premixed combustion and more diffusion combustion, which may be better at oxidizing oil mist in the cylinder. Finally, less premixed combustion means lower rates of pressure rise, which might dislodge less oil from engine surfaces like piston rings. While further work is needed to understand the mechanisms, the variation in emission rates of these compounds may limit their use as traffic-related tracers, as discussed later.

3.3. Effect of DPF

Effects of the DOC + DPF and DPF regeneration on PM and SVOC emissions are summarized in Table 6; effects on individual compounds are shown in Fig. 2. The DPF caused large (>99%) reductions in PM, Σ15PAH, Σ11NPAH, Σ5Hopane and Σ6Sterane emission rates. While emissions increased during regeneration, emission rates remained much lower (83–99%) than those without DPF. This applied to individual compounds as well as the sums. During regeneration, exhaust temperatures are raised to burn off the PM accumulated in the DPF, and thus slight increases in PM and SVOC emissions are expected. The DPF also increased the SOF of the PM since the carbonaceous soot was filtered out by the DPF. Consistent with a previous study (Ratcliff et al., 2010), our data confirmed that the DPF effectively converted particle-bound PAHs and nitro-PAHs.

Table 6.

PM and SVOC emission rates, SOF and TEQs with and without a DOC + DPF.

| After-treatment | Fuel | Engine condition | PM (mg/kWh) | SOF (unitless) | Σ15PAH (ng/kWh) | Σ11NPAH (ng/kWh) | Σ5Hopane (ng/kWh) | Σ6Sterane (ng/kWh) | TEQBAP (ng/kWh) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | 1500 rpm, 600 kPa | 32.9 ± 1.3 | 0.43 ± 0.02 | 546 ± 111 | 47 ± 9 | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 243 ± 8 | 118 ± 13 | |

| w/DOC + DPF | ULSD | 1500 rpm, 600 kPa | 0.1 ± 0.0 | 1.0 ± 0.0 | 1.5 ± 0.2 | 0.034 ± 0.004 | ND | 0.1 ± 0.0 | 0.04 ± 0.02 |

| DOC + DPF regen | 1500 rpm, 500 kPa | 5.7 | 0.9 | 3.2 | 0.12 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

ND: not detected.

Fig. 2.

Effect of DOC + DPF on speciated SVOC emissions. These tests were at low-load. Compounds with missing values were below IDLs.

3.4. Toxicity of engine exhaust

Considering PAHs and NPAHs together, Swedish diesel reduced the TEQB[a]P by 42%–59% for all three conditions; B100 provided 77%–98% reductions (Table 5). These reductions were statistically significant. The DOC + DPF provided huge reductions, e.g., TEQB[a]P dropped by a factor of 2950 (factor of 590 while regenerating, Table 6). These data suggest that toxicity, measured as carcinogenic risk from PAHs and NPAHs, is greatly reduced by the use of DPF and alternative fuels. This is consistent with previous studies that reported lower mutagenic potency of diesel exhaust using biodiesel (Bünger et al., 1998) and Swedish diesel (Westerholm et al., 2001).

Although B100 reduced the total TEQB[a]P of diesel exhaust, it increased 5-nitroacenaphthene emissions during idling, as discussed above. This compound is classified as group 2B (possibly carcinogenic to humans) by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), although its TEF is only small (0.03, (RIDEM, 2008). Given the attention to exposures from idling vehicles, the 5-nitroacenaphthene emissions found while idling with B100 may warrant further investigation.

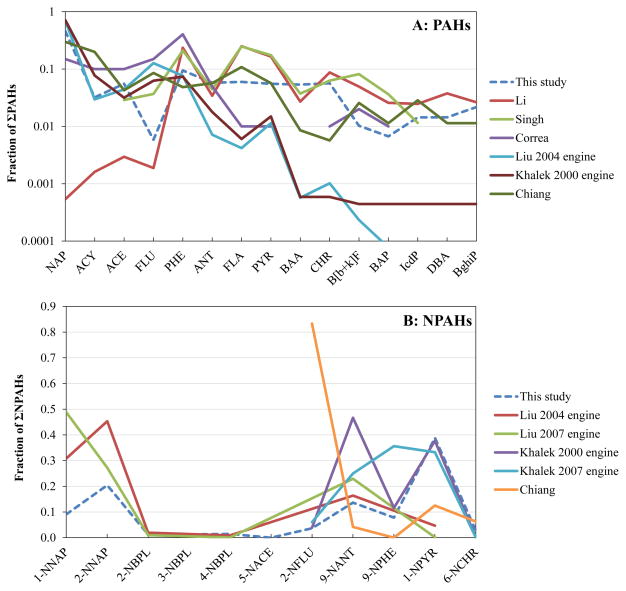

3.5. PAH and NPAH profiles

PAH profiles had high abundances of naphthalene, phenanthrene, fluoranthene and pyrene, and low abundances of high molecular weight compounds (Supplemental Table S5). Overall, the profiles resemble those in the literature (Liu et al., 2010; Khalek et al., 2011) with Spearman correlation coefficients from 0.69 to 0.75 (p < 0.05; Fig. 3). NPAH profiles had high abundances of nitronaphthalenes, 9-nitroanthracene and 1-nitropyrene. While fewer data are available for comparison, this profile correlated closely with one reported for year 2000 engines (Spearman r = 0.90, p = 0.037) (Khalek et al., 2011). While overall agreement is good, abundances of individual compounds can vary considerably among studies, reflecting differences in engine configuration, operating conditions, sampling protocols, and other factors. The more volatile compounds like naphthalene are particularly sensitive to partitioning between vapor and particulate phases (Singh et al., 1993), so studies combining both phases reported high abundances (70–80%) of this compound (Liu et al., 2010; Khalek et al., 2011).

Fig. 3.

Comparison between this study’s profile and profiles in literature. (A) PAHs; (B) NPAHs.

The relative concentrations of engine exhaust emissions of PAHs, NPAHs and PM2.5 varied considerably among studies. In five recent studies (Sharp et al., 2000b, 2000a; Gambino et al., 2001; Liu et al., 2010; Khalek et al., 2011; Chiang et al., 2012), ΣPAH/PM2.5 ratios ranged from 2.2 × 10−5 to 0.23, and ΣNPAH/PM2.5 ratios from 1.3 × 10−6 to 3.2 × 10−4. In the present study, ΣPAH/PM2.5 and ΣNPAH/PM2.5 ratios are 3.2 ×10−5 and 1.2 × 10−6, respectively (Supplemental Table S5). These results highlight large differences in the composition of engine exhaust, which depends on engine type and configurations, operating condition, fuel, control technology, etc.

The variability in the composition of diesel exhaust emissions suggests that PAHs and NPAHs profiles measured using individual engines may not be useful for quantitative apportionments of PM2.5 using receptor models. Rather, composite profiles derived from many vehicles and over multiple conditions should be more representative and useful in this application. Receptor models can also apportion sources of SVOCs in sediments. In this case, profiles should use only the particulate phase since in sediments these contaminants arise mostly from deposition of airborne particulates (Li et al., 2003), and profiles should be expressed as the fraction of ΣPAHs or ΣNPAHs (rather than PM mass). More generally, profiles and specifically the fitting species used in receptor models might focus on those compounds that have similar abundances among studies (e.g., phenanthrene, fluoranthene, pyrene, 1-nitropyrene), and exclude or down-weight compounds with large variability (e.g., naphthalene, benzo[a]pyrene, 2-nitrofluorene). To represent real world vehicle emissions, profiles should represent the actual fleet mix, engine/control technologies, acceleration/deceleration, and environmental conditions present. The profiles in this study, which portray steady-state laboratory conditions for selected test conditions, alone are not suitable for receptor modeling, although they help illustrate how changes in fuels, engine load and engine technology can affect profiles and real world emissions.

Hopanes and steranes have been used as tracers of vehicle exhaust PM (Kleeman et al., 2008, 2009). Our results suggest that fuel type significantly affects hopane and sterane emissions, as well as PAH and NPAH emissions. It may be possible to establish a relationship between hopane/sterane and PAH/NPAH emissions. Emission rates of Σ15PAH, Σ11NPAH, PM2.5 and SOF were significantly correlated to 17α (H)21β(H)-hopane emissions (r = 0.72–0.95; Fig. 4). Emissions of Σ5Hopane, Σ6Sterane and other individual hopane and sterane followed the same trend as 17α(H) 21β;(H)-hopane.

Fig. 4.

Emission rates of PAHs, NPAHs, PM, and SOF versus 17α(H)21β(H)-hopane.

If the ratio of 17α(H)21β(H)-hopane to Σ15PAH/Σ11NPAH remains constant, then 17α(H)21β(H)-hopane can be used to apportion traffic-originated PAHs/NPAHs. This assumes that 17α(H) 21β(H)-hopane comes from only vehicle emissions, and that the ratio remains constant across different engines and engine types. However, six studies in the literature (Phuleria et al., 2006) show ratios of Σ9PAH (FLA to IND)/17α(H)21β(H)-hopane and FLA/17α(H) 21β(H)-hopane ranging from 0.6 to 5400 and 0.04 to 3000, respectively; the present study obtained ratios of 95 and 21. PM2.5/17α(H)21β(H)-hopane ratios also vary, e.g., from 2000 to 227,000 in three studies (Rogge et al., 1993; Schauer et al., 1999, 2002; Liu et al., 2010); the present study shows a ratio of 1.2 × 107. Such variation limits the value of hopanes and steranes as quantitative tracers of diesel exhaust emissions. Still, these compounds may have diagnostic and qualitative value in detecting vehicle contributions to PAHs, NPAHs and ambient PM.

4. Conclusions

This study characterized exhaust emissions of PM2.5, PAHs, NPAHs, steranes and hopanes from a heavy-duty diesel engine for three fuels, three engine conditions, and the effect of a DOC + DPF. Swedish diesel, biodiesel and the DOC + DPF significantly reduced emissions of PM2.5, PAHs, NPAHs, hopanes and steranes, although emissions of PM2.5 and several compounds (benzo[k]fluoranthene and 5-nitroacenaphthene) increased during idling with biodiesel. Emission rates of PM2.5 and SVOCs increased with engine load, with the important exception that PM2.5 emissions increased during idling with B100. The toxicity of diesel exhaust in terms of carcinogenic risk was reduced using the alternative fuels and the DOC + DPF. A PAH/NPAH profile, developed by combining emission measurements during idling and load and accounting for variability, was consistent with earlier studies for most PAHs and provides new data for NPAHs. Emissions of petroleum biomarkers hopanes and steranes were significantly correlated with PAHs, NPAHs and PM2.5, but abundances varied considerably, suggesting that these compounds can provide only qualitative or diagnostic results when used in apportionment studies.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

Emissions of PM and 36 SVOCs are measured in exhaust from a heavy-duty diesel engine.

Three engine conditions, three fuels and two after-treatment systems are tested.

Under load, PM and SVOC emissions using biodiesel and low aromatic diesel are reduced.

While idling, PM and 5-nitroacenaphthene emissions increase with biodiesel.

DOC + DPF after-treatment is highly effective in reducing PM and SVOC emissions.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank William Ruona of Ford Motor Company for his assistance with engine and DPF regeneration control. This study was supported by US EPA grant GL00E00690-0 entitled PAHs, Nitro-PAHs & Diesel Exhaust Toxics in the Great Lakes: Apportionments, Impacts and Risks. The National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, National Institutes of Health provided additional support in grant P30ES017885 entitled Lifestage Exposures and Adult Disease.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2014.11.046.

References

- Bagley ST, Gratz LD, Johnson JH, McDonald JF. Effects of an oxidation catalytic converter and a biodiesel fuel on the chemical, mutagenic, and particle size characteristics of emissions from a diesel engine. Environ Sci Technol. 1998;32 (9):1183–1191. [Google Scholar]

- Bünger J, Krahl J, Franke HU, Munack A, Hallier E. Mutagenic and cytotoxic effects of exhaust particulate matter of biodiesel compared to fossil diesel fuel. Mutat Res Genet Toxicol Environ Mutagen. 1998;415 (1):13–23. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5718(98)00039-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CFR. Code of Federal Regulations Title 40 Part 1065: Engine Testing Procedures. U.S. National Archives and Records Administration; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung K, Ntziachristos L, Tzamkiozis T, Schauer J, Samaras Z, Moore K, Sioutas C. Emissions of particulate trace elements, metals and organic species from gasoline, diesel, and biodiesel passenger vehicles and their relation to oxidative potential. Aerosol Sci Technol. 2010;44 (7):500–513. [Google Scholar]

- Chiang HL, Lai YM, Chang SY. Pollutant constituents of exhaust emitted from light-duty diesel vehicles. Atmos Environ. 2012;47:399–406. [Google Scholar]

- Chin JY, Batterman SA, Northrop WF, Bohac SV, Assanis DN. Gaseous and particulate emissions from diesel engines at idle and under load: comparison of biodiesel blend and ultralow sulfur diesel fuels. Energy Fuels. 2012;26 (11):6737–6748. doi: 10.1021/ef300421h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christian V, Knopf F, Jaschek A, Schneider W. Eine neue Messmethodik der Bosch-Zahl mit erhöhter Empfindlichkeit. MTZ. 1993;54 (1):16–22. [Google Scholar]

- Correa SM, Arbilla G. Aromatic hydrocarbons emissions in diesel and biodiesel exhaust. Atmos Environ. 2006;40 (35):6821–6826. [Google Scholar]

- Coutant RW, Brown L, Chuang JC, Riggin RM, Lewis RG. Phase distribution and artifact formation in ambient air sampling for polynuclear aromatic hydrocarbons. Atmos Environ 1967. 1988;22 (2):403–409. [Google Scholar]

- Di Y, Cheung C, Huang Z. Comparison of the effect of biodiesel-diesel and ethanol-diesel on the particulate emissions of a direct injection diesel engine. Aerosol Sci Technol. 2009;43 (5):455–465. [Google Scholar]

- EPA. A Comprehensive Analysis of Biodiesel Impacts on Exhaust Emissions. U.S. Enivronmental Protection Agency; Washington, D.C: 2001. EPA420-P-02–001. [Google Scholar]

- EPA. Development of a Relative Potency Factor (RPF) Approach for Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon (PAH) Mixtures (External Review Draft) U.S. Environmental Protection Agency; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- EPA. Diesel Fuel. 2012 Retrieved Sep 23, 2013, from: http://www.epa.gov/otaq/fuels/dieselfuels/

- EPA. National Clean Diesel Campaign (NCDC): Diesel Retrofit Devices. 2013 Retrieved Sep 23, 2013, from: http://www.epa.gov/otaq/diesel/technologies/retrofits.htm.

- Gambino M, Iannaccone S, Battistelli CL, Crebelli R, Iamiceli AL, Turrio Baldassarri L. International Combustion Engines. 2001. Exhaust Emission Toxicity Evaluation for Heavy Duty Diesel and Natural Gas Engines. Part I: Regulated and Unregulated Emissions with Diesel Fuel and a Blend of Diesel Fuel and Biodiesel. SAE_NA Technical Paper Series 2001-01-044. [Google Scholar]

- Hartung A, Kraft J, Schulze J, Kiess H, Lies KH. The identification of nitrated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in diesel particulate extracts and their potential formation as artifacts during particulate collection. Chroma-tographia. 1984;19 (1):269–273. [Google Scholar]

- Heeb NV, Schmid P, Kohler M, Gujer E, Zennegg M, Wenger D, Wichser A, Ulrich A, Gfeller U, Honegger P. Secondary effects of catalytic diesel particulate filters: conversion of PAHs versus formation of nitro-PAHs. Environ Sci Technol. 2008;42 (10):3773–3779. doi: 10.1021/es7026949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heeb NV, Schmid P, Kohler M, Gujer E, Zennegg M, Wenger D, Wichser A, Ulrich A, Gfeller U, Honegger P. Impact of low-and high-oxidation diesel particulate filters on genotoxic exhaust constituents. Environ Sci Technol. 2010;44 (3):1078–1084. doi: 10.1021/es9019222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hori S, Narusawa K. The influence of fuel components on PM and PAH exhaust emissions from a DI diesel engine-effects of pyrene and sulfur contents. SAE Trans. 2001;110 (4):2386–2392. [Google Scholar]

- Huai T, Shah SD, Wayne Miller J, Younglove T, Chernich DJ, Ayala A. Analysis of heavy-duty diesel truck activity and emissions data. Atmos Environ. 2006;40 (13):2333–2344. [Google Scholar]

- Huang L, Bohac SV, Chernyak SM, Batterman SA. Composition and integrity of PAHs, Nitro-PAHs, hopanes, and steranes in diesel exhaust particulate matter. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2013;224 (8):1–14. doi: 10.1007/s11270-013-1630-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang XF, He LY, Hu M, Zhang YH. Annual variation of particulate organic compounds in PM2.5 in the urban atmosphere of Beijing. Atmos Environ. 2006;40 (14):2449–2458. [Google Scholar]

- Karavalakis G, Deves G, Fontaras G, Stournas S, Samaras Z, Bakeas E. The impact of soy-based biodiesel on PAH, nitro-PAH and oxy-PAH emissions from a passenger car operated over regulated and nonregulated driving cycles. Fuel. 2010;89 (12):3876–3883. [Google Scholar]

- Khalek IA, Bougher TL, Merritt PM, Zielinska B. Regulated and unregulated emissions from highway heavy-duty diesel engines complying with US Environmental Protection Agency 2007 emissions standards. J Air Waste Manag Assoc. 2011;61 (4):427–442. doi: 10.3155/1047-3289.61.4.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleeman MJ, Riddle SG, Robert MA, Jakober CA. Lubricating oil and fuel contributions to particulate matter emissions from light-duty gasoline and heavy-duty diesel vehicles. Environ Sci Technol. 2008;42 (1):235–242. doi: 10.1021/es071054c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleeman MJ, Riddle SG, Robert MA, Jakober CA, Fine PM, Hays MD, Schauer JJ, Hannigan MP. Source apportionment of fine (PM1.8) and ultrafine (PM0.1) airborne particulate matter during a severe winter pollution episode. Environ Sci Technol. 2009;43 (2):272–279. doi: 10.1021/es800400m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapuerta M, Armas O, Rodriguez-Fernandez J. Effect of biodiesel fuels on diesel engine emissions. Prog Energy Combust Sci. 2008;34 (2):198–223. [Google Scholar]

- Lea-Langton A, Li H, Andrews G. SAE Technical Paper 01–1811. 2008. Comparison of Particulate PAH Emissions for Diesel, Biodiesel and Cooking Oil Using a Heavy Duty DI Diesel Engine. [Google Scholar]

- Li A, Jang JK, Scheff PA. Application of EPA CMB8. 2 model for source apportionment of sediment PAHs in Lake Calumet, Chicago. Environ Sci Technol. 2003;37 (13):2958–2965. doi: 10.1021/es026309v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lies K, Hartung A, Postulka A, Gring H, Schulze J. Composition of diesel exhaust with particular reference to particle bound organics including formation of artifacts. Dev Toxicol Environ Sci. 1985;13:65–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu ZG, Berg DR, Vasys VN, Dettmann ME, Zielinska B, Schauer JJ. Analysis of C1, C2, and C10 through C33 particle-phase and semi-volatile organic compound emissions from heavy-duty diesel engines. Atmos Environ. 2010;44 (8):1108–1115. [Google Scholar]

- Lutsey N, Brodrick CJ, Sperling D, Oglesby C. Heavy-duty truck idling characteristics: results from a nationwide truck survey. Transp Res Rec J Transp Res Board. 2004;1880 (1):29–38. [Google Scholar]

- Magara-Gomez KT, Olson MR, Okuda T, Walz KA, Schauer JJ. Sensitivity of diesel particulate material emissions and composition to blends of petroleum diesel and biodiesel fuel. Aerosol Sci Technol. 2012;46 (10):1109–1118. [Google Scholar]

- Matti Maricq M. Chemical characterization of particulate emissions from diesel engines: a review. J Aerosol Sci. 2007;38 (11):1079–1118. [Google Scholar]

- Nisbet IC, LaGoy PK. Toxic equivalency factors (TEFs) for polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 1992;16 (3):290–300. doi: 10.1016/0273-2300(92)90009-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northrop WF, Chin JY, Assanis DN, Bohac SV. Comparison of filter smoke number and elemental carbon mass from partially premixed low temperature combustion in a direct-injection diesel engine. J Eng Gas Turbines Power. 2011;133 (10):102804. [Google Scholar]

- Peters KE, Walters C, Moldowan J. The Biomarker Guide. Biomarkers and Isotopes in the Environment and Human History. 2007;1 [Google Scholar]

- Phuleria HC, Geller MD, Fine PM, Sioutas C. Size-resolved emissions of organic tracers from light-and heavy-duty vehicles measured in a California roadway tunnel. Environ Sci Technol. 2006;40 (13):4109–4118. doi: 10.1021/es052186d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliff MA, Dane AJ, Williams A, Ireland J, Luecke J, McCormick RL, Voorhees KJ. Diesel particle filter and fuel effects on heavy-duty diesel engine emissions. Environ Sci Technol. 2010;44 (21):8343–8349. doi: 10.1021/es1008032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RIDEM. State of Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management. 2008. Rhode Island Air Toxics Guideline. [Google Scholar]

- Rogge WF, Hildemann LM, Mazurek MA, Cass GR, Simoneit BR. Sources of fine organic aerosol. 2 Noncatalyst and catalyst-equipped automobiles and heavy-duty diesel trucks. Environ Sci Technol. 1993;27 (4):636–651. [Google Scholar]

- Schauer C, Niessner R, Pöschl U. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in urban air particulate matter: decadal and seasonal trends, chemical degradation, and sampling artifacts. Environ Sci Technol. 2003;37 (13):2861–2868. doi: 10.1021/es034059s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schauer JJ, Kleeman MJ, Cass GR, Simoneit BR. Measurement of emissions from air pollution sources. 2 C1 through C30 organic compounds from medium duty diesel trucks. Environ Sci Technol. 1999;33 (10):1578–1587. [Google Scholar]

- Schauer JJ, Kleeman MJ, Cass GR, Simoneit BR. Measurement of emissions from air pollution sources. 5 C1-C32 organic compounds from gasoline-powered motor vehicles. Environ Sci Technol. 2002;36 (6):1169–1180. doi: 10.1021/es0108077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoeny R, Poirier K. Provisional Guidance for Quantitative Risk Assessment of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Schuetzle D, Perez JM. Factors influencing the emissions of nitrated-polynuclear aromatic hydrocarbons (nitro-PAH) from diesel engines. J Air Pollut Control Assoc. 1983;33 (8):751–755. [Google Scholar]

- Sharp CA, Howell S, Jobe J. SAE Technical Paper 2000-01-1967. 2000a. The Effect of Biodiesel Fuels on Transient Emissions from Modern Diesel Engines-part I: Regulated Emissions and Performance. [Google Scholar]

- Sharp CA, Howell S, Jobe J. SAE Technical Paper 2000-01-1968. 2000b. The Effect of Biodiesel Fuels on Transient Emissions from Modern Diesel Engines, Part II Unregulated Emissions and Chemical Characterization. [Google Scholar]

- Simcik MF, Eisenreich SJ, Lioy PJ. Source apportionment and source/sink relationships of PAHs in the coastal atmosphere of Chicago and Lake Michigan. Atmos Environ. 1999;33 (30):5071–5079. [Google Scholar]

- Singh AK, Gin M, Ni F, Christensen E. A source-receptor method for determining non-point sources of PAHs to the Milwaukee Harbor Estuary. Water Sci Technol. 1993;28 (8–9):91–102. [Google Scholar]

- Stenberg U, Alsberg T, Westerholm R. Applicability of a cryogradient technique for the enrichment of PAH from automobile exhausts: demonstration of methodology and evaluation experiments. Environ Health Perspect. 1983;47:43. doi: 10.1289/ehp.834743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka S, Takizawa H, Shimizu T, Sanse K. Effect of fuel compositions on PAH in particulate matter from DI diesel engine. SAE Trans. 1998;107:1941–1951. [Google Scholar]

- Westerholm R, Christensen A, Törnqvist M, Ehrenberg L, Rannug U, Sjögren M, Rafter J, Soontjens C, Almén J, Grägg K. Comparison of exhaust emissions from Swedish environmental classified diesel fuel (MK1) and European Program on Emissions, Fuels and Engine Technologies (EPEFE) reference fuel: a chemical and biological characterization, with viewpoints on cancer risk. Environ Sci Technol. 2001;35 (9):1748–1754. doi: 10.1021/es000113i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang ZH, Balasubramanian R. Physicochemical and toxicological characteristics of particulate matter emitted from a non-road diesel engine: comparative evaluation of biodiesel-diesel and butanol-diesel blends. J Hazard Mater. 2014;264:395–402. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2013.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou L, Atkinson S. Characterising vehicle emissions from the burning of biodiesel made from vegetable oil. Environ Technol. 2003;24 (10):1253–1260. doi: 10.1080/09593330309385667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.