Abstract

Recent clinical studies indicate that meropenem, a β-lactam antibiotic, is a promising candidate for therapy of drug-resistant tuberculosis. However, meropenem is chemically unstable, requires frequent intravenous injection, and must be combined with a β-lactamase inhibitor (clavulanate) for optimal activity. Here, we report that faropenem, a stable and orally bioavailable β-lactam, efficiently kills Mycobacterium tuberculosis even in the absence of clavulanate. The target enzymes, l,d-transpeptidases, were inactivated 6- to 22-fold more efficiently by faropenem than by meropenem. Using a real-time assay based on quantitative time-lapse microscopy and microfluidics, we demonstrate the superiority of faropenem to the frontline antituberculosis drug isoniazid in its ability to induce the rapid cytolysis of single cells. Faropenem also showed superior activity against a cryptic subpopulation of nongrowing but metabolically active cells, which may correspond to the viable but nonculturable forms believed to be responsible for relapses following prolonged chemotherapy. These results identify faropenem to be a potential candidate for alternative therapy of drug-resistant tuberculosis.

INTRODUCTION

Despite advances in health care and access to antimicrobial drugs, tuberculosis (TB) continues to be one of the leading causes of global morbidity and mortality (1). In recent years, anti-TB chemotherapy has been increasingly compromised by the global emergence and spread of multidrug-resistant (MDR) and extensively drug-resistant (XDR) disease, which has so far been reported in 100 countries (1, 2). Although the current pipeline of novel anti-TB drugs and regimens includes several that have advanced into human clinical trials, repositioning of existing drugs that have already been approved for clinical use for conditions other than TB is an attractive alternative (3–5). A significant advantage of this approach is that the toxicology and pharmacokinetic parameters of approved drugs are already known, thus reducing the time and cost required to bring a repositioned compound into the anti-TB armamentarium (6).

Since their discovery more than 80 years ago, β-lactams have become one of the most important classes of antibiotics for the treatment of bacterial infections, and today, more than half of the antibacterials used globally for medical purposes are β-lactams (7). Over the past few decades there has been continuous research and development, mainly driven by the emergence of microbial resistance, of newer classes of β-lactams that escape hydrolysis by β-lactamases (e.g., carbapenems) or inhibit these enzymes (e.g., clavulanate) (8, 9). Despite their remarkable success in the treatment of infections caused by both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, β-lactams have not been routinely used to treat TB because Mycobacterium tuberculosis is naturally resistant to these compounds due to its thick, relatively impermeable cell walls and due to the production of a broad-spectrum Ambler class A β-lactamase (10, 11). Nevertheless, the combination of meropenem (a carbapenem) with clavulanate was recently shown to be bactericidal against M. tuberculosis in vitro (12, 13). Carbapenems have been demonstrated to have modest activity in mouse models of TB (14–16), which are often problematic due to the sensitivity of carbapenems to degradation by murine dehydropeptidase (17). More importantly, encouraging results have been obtained in case series of XDR-TB patients treated with a combination of meropenem plus clavulanate (18–20).

Despite preliminary evidence of clinical efficacy, the difficulty of administering meropenem-clavulanate is a major obstacle to its adoption as an alternative therapy for TB. Due to its poor oral availability and short half-life, meropenem must be administered by frequent intravenous injections or continuously by intravenous infusion. In a recent case study, XDR-TB patients were treated with meropenem-clavulanate administered three times daily via the intravenous route (20), a regimen that is too complex and costly for widespread application in high-burden, resource-poor countries. Faropenem is an orally bioavailable (72 to 84% bioavailability) penem antibiotic that is more resistant to hydrolysis by β-lactamases than cephalosporins and carbapenems are (21, 22). This unconventional β-lactam has demonstrated excellent activity against common respiratory pathogens, and it has already been approved for use in humans (23, 24). Based on these favorable characteristics, we decided to evaluate the efficacy of faropenem against M. tuberculosis in order to ascertain its potential as an alternative therapeutic agent against MDR- and XDR-TB.

Using in vitro assays, we compared the efficiency of faropenem and meropenem in their ability to inhibit the l,d-transpeptidases (LDTs), which perform the last cross-linking step of peptidoglycan synthesis (25, 26). These enzymes catalyze the formation of 70 to 80% of the peptidoglycan cross-links (13, 25) and are therefore likely to be the main targets of β-lactams in M. tuberculosis. However, β-lactams have additional targets in this bacterium, including the d,d-carboxypeptidases, which generate the essential substrate of the LDTs (13). The target of β-lactams may also include classical d,d-transpeptidases, since these enzymes may have essential roles in cell wall synthesis, despite their marginal contribution to peptidoglycan cross-linking in M. tuberculosis (27). We employed real-time single-cell assays based on time-lapse microscopy and microfluidics for quantitative analysis of the bactericidal activity of these compounds against various bacterial phenotypic variants, including a subpopulation of nongrowing but metabolically active (NGMA) bacilli (28–30). Our results provide strong preclinical support to justify the advancement of faropenem into phase II clinical trials in TB patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria and growth conditions.

Mycobacterium tuberculosis Erdman and H37Rv and strains derived from strains Erdman and H37Rv were grown in Middlebrook 7H9 liquid medium (Difco) containing 0.5% albumin, 0.085% NaCl, 0.2% glucose, 0.5% glycerol, and 0.05% Tween 80 or on Middlebrook 7H10 solid medium (Difco) containing 10% oleic acid-albumin-dextrose-catalase (Difco) and 0.5% glycerol. Uropathogenic Escherichia coli CFT073 and strains derived from strain CFT073 were grown in LB medium (Sigma). Bacteria were grown in 30-ml square medium bottles (Nalgene) in an orbital shaker at 37°C to mid-log phase (optical density at 600 nm [OD600], 0.5). Aliquots were stored in 15% glycerol at −80°C and thawed at room temperature before use; individual aliquots were used once and discarded.

MIC determination.

MIC measurements were performed in 96-well flat-bottom polystyrene microtiter plates. Ten 2-fold drug dilutions in dimethyl sulfoxide starting at 50 mM were prepared, and 5 μl of each dilution was added to 95 μl of 7H9 medium. As a positive control, eight 2-fold dilutions of isoniazid starting at 160 μg/ml were prepared, and 5 μl of each dilution was added to 95 μl of 7H9 medium. The inoculum was adjusted to ∼1 × 107 CFU/ml and diluted 100-fold in 7H9 medium, and 100 μl of the diluted cell suspension was added to each well. Microtiter plates were placed in a sealed box to prevent evaporation and incubated at 37°C without agitation for 6 days. A resazurin solution was prepared by dissolving one tablet of resazurin (VWR International Ltd.) in 30 ml sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and 25 μl of this solution was added to each well. After 48 h, fluorescence (excitation, 530 nm; emission, 590 nm) was measured using a SpectraMax M5 microplate reader (Molecular Devices).

Luciferase-based MIC determination.

MIC measurements were performed in 96-well black flat-bottom microtiter plates (Corning). M. tuberculosis Erdman was transformed with plasmid pEG200, which expresses bacterial luciferase (31), and grown at 37°C to mid-log phase (OD600, 0.5) in 7H9 medium. The culture was diluted 100-fold in fresh medium, and 100 μl of the cell suspension was added to wells containing 2-fold serial dilutions of antibiotics. Faropenem was tested in the 0.0015- to 200-μg/ml range in the presence or absence of 5 μg/ml potassium clavulanate. Bioluminescence was measured after 4 and 7 days of incubation using a Tecan Infinite M200 microplate reader. The MIC was defined as the lowest antibiotic concentration that decreased bioluminescence by 90% compared to the bioluminescence of the no-drug control.

Production and purification of LdtMt1 and BlaC from M. tuberculosis H37Rv.

l,d-Transpeptidase paralogue 1 from M. tuberculosis (LdtMt1) and the β-lactamase BlaC were produced in E. coli BL21(DE3) and purified by Ni2+-nitrilotriacetic acid affinity and size exclusion chromatographies as previously described (26, 32, 33).

Mass spectrometry analyses.

The formation of drug-enzyme adducts was tested by incubating LdtMt1 (20 μM) with faropenem or meropenem (100 μM) at 37°C in 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0) for 1 h. Five microliters of acetonitrile and 1 μl of 1% formic acid were extemporaneously added, and the reaction mixture was directly injected into the mass spectrometer (Qstar Pulsar I; Applied Biosystems). Spectra were acquired in the positive mode as previously described (34).

Determination of LdtMt1 catalytic constants kinact, Kapp, and khydrol.

LdtMt1 inactivation is a two-step reaction involving the reversible formation of a tetrahedral intermediate (oxyanion [EIox]), followed by irreversible acylation of the active-site cysteine (35, 36). The resulting acyl enzyme, EI*, is hydrolyzed at a low rate. The kinetic constants for LdtMt1 acylation by faropenem (sodium hemipentahydrate; GlaxoSmithKline) and meropenem (trihydrate; AstraZeneca) were determined in 100 mM sodium phosphate (pH 6.0) by measuring the decrease in the absorbance at 299 nm, which results from opening of the antibiotic β-lactam ring (Δε299 for faropenem and meropenem = −5,000 and −7,100 M−1 cm−1, respectively). Experiments were performed with six concentrations of each antibiotic with a stopped-flow apparatus (RX-2000; Applied Photophysics) coupled to a Cary 300-Bio spectrophotometer (Varian SA) at 10°C. For each time course, regression analysis was used with the equation , in which [Etotal] is the total enzyme concentration, kobs is a constant, and t is time (35). The first-order constant (kobs) was plotted as a function of the antibiotic concentration. Regression analysis was performed using the equation kobs = kinact[I]/(Kapp + [I]), where [I] is the antibiotic concentration, kinact is the first-order rate constant for LdtMt1 acylation, and Kapp is a constant. The hydrolysis rate (khydrol) of the acyl enzymes was determined at 299 nm in sodium phosphate buffer (100 mM, pH 6.0) at 20°C, as described below (26, 32).

Kinetics of acyl enzyme hydrolysis.

To determine the hydrolysis rate (khydrol) of the acyl enzymes (see Fig. 1B), β-lactams (100 μM) were incubated with increasing concentrations of LdtMt1 (0, 2.5, 5, and 10 μM) in 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0). Enzyme turnover was determined at 20°C by measuring the decrease in the absorbance at 299 nm for carbapenems on a Cary 100 spectrophotometer (Cary 100-Bio; Varian SA). The hydrolysis velocity (V) was plotted as a function of the LdtMt1 concentration, and enzyme turnover (khydrol) was deduced from the slope. This provides an estimate of the rate of hydrolysis of the acyl enzyme, since this is the rate-limiting step of the full catalytic cycle.

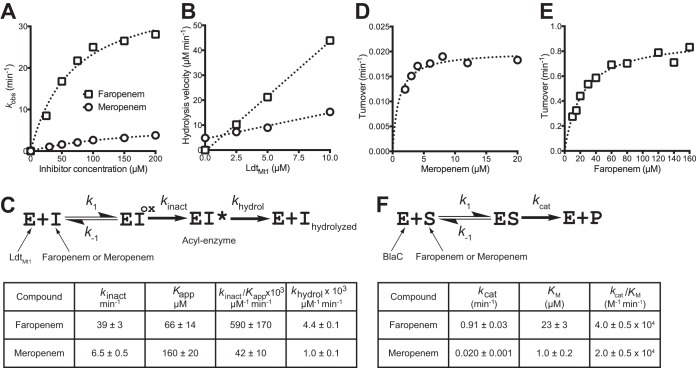

FIG 1.

Biochemical characterization of β-lactam activity. Spectrophotometric determination of kinetic constants for LdtMt1 inactivation by faropenem and meropenem (A to C) and for hydrolysis of these antibiotics by BlaC (D to F). The first-order constants (kobs) were determined for six drug concentrations by measuring the absorbance decrease (30-s time scale), which results from opening of the antibiotic β-lactam ring upon enzyme acylation, and regression analysis with the equation , in which [Etotal] is the total enzyme concentration, kobs is a constant, and t is time. The resulting kobs values were plotted as a function of antibiotic concentrations (A), and kinetic constants kinact and Kapp (C) were deduced by regression analysis using the equation kobs = kinact[I]/(Kapp + [I]), where [I] is the antibiotic concentration, kinact is the first-order rate constant for LdtMt1 acylation, and Kapp is a constant. The hydrolysis velocities of faropenem and meropenem (1,000-min time scale) were plotted as a function of the LdtMt1 concentration (B), and enzyme turnover (khydrol) was deduced from the slope (C). This provides an estimate of the rate of hydrolysis of the acyl enzyme since this is the rate-limiting step of the full catalytic cycle. EIox, oxyanion. (D to F) Determination of kinetic constants for hydrolysis of faropenem and meropenem by β-lactamase BlaC. Turnover numbers were determined for various concentrations of meropenem (D) and faropenem (E), and regression analysis was performed using the equation turnover number = kcat[S]/(Km + [S]) (F), where [S] is the antibiotic concentration.

Kinetics of β-lactam hydrolysis by BlaC.

The velocities of faropenem and meropenem hydrolysis were determined at 258 and 299 nm, respectively, in 100 mM MES (morpholineethanesulfonic acid; pH 6.4) at 20°C for 500 min. BlaC concentrations were 0.17, 0.35, or 1 μM for faropenem and 0.5 or 1 μM for meropenem. Velocities were plotted against the substrate concentration and fitted to the classical Michaelis-Menten hyperbola.

Time-kill kinetic assays.

M. tuberculosis Erdman was grown in Middlebrook 7H9 medium at 37°C with aeration to mid-log phase (OD600, 0.5). The cultures were diluted 10-fold (OD600, 0.05) in fresh 7H9 medium containing isoniazid (Sigma), faropenem (GlaxoSmithKline), or meropenem (LKT Laboratories), with or without addition of potassium clavulanate (Sigma). Cultures were further incubated with aeration at 37°C. Aliquots of cells were removed, collected by centrifugation, and washed with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 80. Serial dilutions of washed cells were plated on 7H10 medium, and the numbers of CFU were scored after incubation of the plates at 37°C for 3 to 4 weeks. In the experiments whose results are shown in Fig. 2B and C, the antibiotics were added once at time zero.

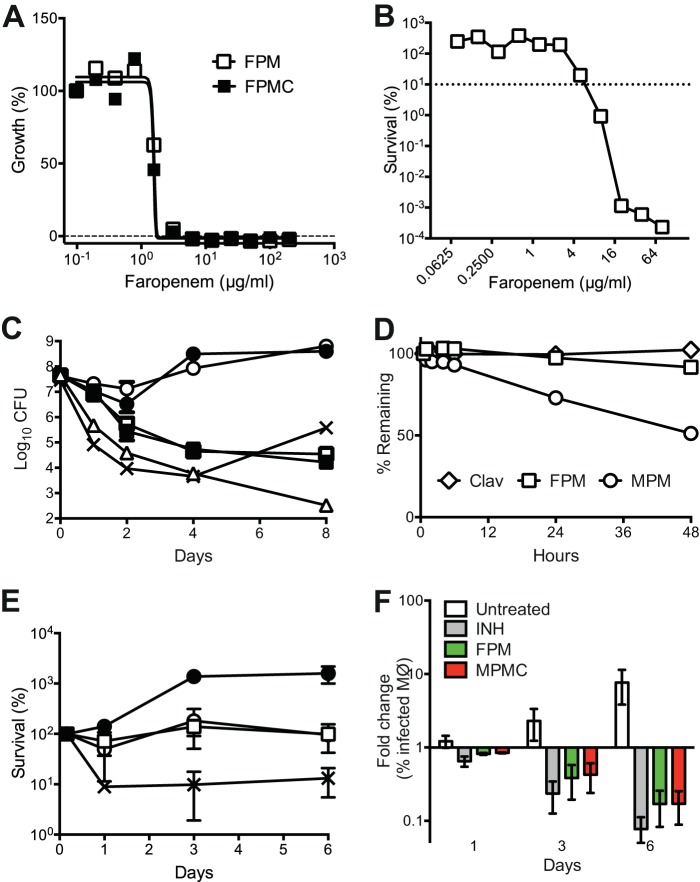

FIG 2.

Activity of faropenem against extracellular and intracellular M. tuberculosis. (A) Bacteria expressing luciferase were incubated for 7 days in 7H9 medium containing different concentrations of faropenem (FPM) or faropenem plus clavulanate (FPMC). Growth was measured using a luciferase-based assay, and the data were normalized to the values obtained in the absence of antibiotic. Results are representative of those from four experiments. (B) Log-phase cultures were exposed for 6 days to different concentrations of faropenem and plated to measure the number of CFU. Values were normalized to those for the untreated controls. Results are representative of those from two experiments. (C) Log-phase cultures were exposed to antibiotics with (filled symbols) or without (empty symbols) 2.5 μg/ml clavulanate. Circles, meropenem (8 μg/ml; ∼26× MIC with clavulanate, ∼3× MIC without clavulanate); squares, faropenem (8 μg/ml; ∼6× MIC with or without clavulanate); triangles, faropenem (28 μg/ml; ∼21× MIC); crosses, 0.5 μg/ml isoniazid (∼20× MIC). At 0, 1, 2, 4, and 8 days after antibiotic addition, aliquots were washed and plated to measure the number of CFU. Results are means ± SEMs from three experiments. The rebound of the numbers of CFU at 8 days in the culture exposed to isoniazid was due to the outgrowth of drug-resistant variants. (D) The stability of compounds in 7H9 medium was measured by HPLC-UV analysis. Clav, clavulanic acid; MPM, meropenem. (E and F) Bacteria expressing GFP were grown in RAW macrophages and left untreated (closed circles) or treated with 56 μg/ml faropenem (open squares), 50 μg/ml meropenem plus 2.5 μg/ml clavulanate (open circles), or 0.75 μg/ml isoniazid (crosses). (E) Macrophage lysates were plated at 0 h and at 1, 3, and 6 days postinfection to measure the number of CFU. Data are plotted as percent survival normalized to the number of organisms at 0 h. (F) The fraction of macrophages (Mϕ) containing GFP-positive M. tuberculosis was measured by flow cytometry at 1, 3, and 6 days postinfection. INH, isoniazid; FPM, faropenem; MPMC, meropenem plus clavulanate. Results are means ± SEMs from three experiments.

Stability of compounds.

Faropenem (100 μg/ml), meropenem (100 μg/ml), and clavulanate (2.5 μg/ml) were prepared in 7H9 medium and incubated at 37°C for 48 h. Aliquots were collected, diluted 1:3 with precipitating agent (a 1:3 mixture of acetone and methanol), and centrifuged at 6,150 × g for 10 min, and the supernatants were analyzed by high-pressure liquid chromatography with UV detection (HPLC-UV; faropenem, 318 nm; meropenem, 307 nm; clavulanate, 220 nm) on a Waters 2795 separation module with a Waters 2996 photodiode array detector. Faropenem and meropenem samples were run on a Phenomenex Luna C18 column (50 by 3.0 mm; particle size, 5 μm) with 0.1% formic acid-acetone as the mobile phase and were diluted 1:4 in water before analysis to avoid elution with the solvent front. Clavulanate samples were run on a Chromolith RP-18e column (100 by 4.6 mm) with 0.1% formic acid (isocratic, 100%) as the mobile phase.

Intracellular killing assays.

RAW macrophages were grown in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium containing l-glutamine and sodium pyruvate (PAA Laboratories) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. About 2.5 × 104 cells were seeded into each well of a 48-well plate and were infected with green fluorescent protein (GFP)-expressing M. tuberculosis (MTB_NDT1) at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10:1 for 4 h. After infection, the monolayers were washed three times with fresh medium to remove nonadherent bacteria and then exposed to fresh medium with or without isoniazid (0.75 μg/ml), faropenem (7, 28, or 56 μg/ml), or meropenem (5, 25, or 50 μg/ml) plus clavulanate (2.5 μg/ml). Medium (containing antibiotics) was changed every 24 h. At various time points, macrophages were washed once with 1× PBS and then lysed using 0.5% Triton X-100. The macrophage lysates were diluted in PBS containing 0.05% Tween 80, serial dilutions were plated on 7H10 agar, and bacterial CFU were enumerated after incubation of the plates at 37°C for 3 to 4 weeks. For analysis of the infected macrophages by flow cytometry, the cells were washed once with 1× PBS before being resuspended in PBS. Cells were analyzed by flow cytometry using a BD Accuri C6 flow cytometer. The threshold was set at 80,000, gates were drawn to exclude clumps and debris, and 50,000 gated events were acquired for each sample. RAW macrophages infected with nonfluorescent M. tuberculosis were used to determine the background fluorescence gates. The fraction of infected cells was calculated from the number of events exhibiting fluorescence above this background level.

Mouse model of tuberculosis chemotherapy.

The therapeutic efficacy of faropenem was tested in an murine infection model of acute tuberculosis as described previously (37). All animal studies were ethically reviewed and carried out in accordance with European Directive 86/609/EEC and the GlaxoSmithKline policy on the care, welfare, and treatment of animals. Adult female C57BL/6J mice were infected with 1 × 105 CFU of M. tuberculosis H37Rv by the intratracheal route. This procedure consistently results in the recovery of 3 × 104 to 6 × 104 CFU per mouse at 24 h postinoculation. The intratracheal route of infection was chosen because of its reproducibility and ease of implementation in an industrial drug discovery environment. Groups of animals were treated with compounds administered orally four times a day for 7 days starting on day 1 postinfection and received one final dose on day 8. The doses administered were 500 mg/kg of body weight faropenem medoxomil, 25 mg/kg clavulanate, and 200 mg/kg probenecid. On day 9 postinfection, the lungs were harvested and bacterial loads were enumerated by plating lung homogenates on 7H10 medium and counting the colonies after incubation at 37°C for 2 to 3 weeks.

Pharmacokinetics.

Faropenem (500 mg/kg), alone or in combination with probenecid (200 mg/kg) and clavulanic acid (25 mg/kg), was administered in 1% methylcellulose in PBS to adult female C57BL/6J mice via the oral route (gavage). Blood samples were collected at 0.25, 0.5, 1, 3, 4, 6, 8, and 24 h after administration and analyzed by liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry. Three mice were used for each time point.

Time-lapse microscopy.

A derivative of M. tuberculosis strain Erdman expressing GFP (MTB_NDT1) was constructed by cloning gfp downstream of a strong constitutive promoter (provided by Sabine Ehrt, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, NY) in vector pND235, which carries the mycobacteriophage L5 attP-int sequences, and integrating this cassette into the chromosomal attB site. Cells were grown in 7H9 medium at 37°C with aeration to mid-log phase (OD600, 0.5). A derivative of uropathogenic E. coli CFT073 expressing yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) was constructed by transformation with plasmid pZA32-YFP, which expresses yfp from a strong constitutive promoter (38). Cells were grown overnight in LB medium at 37°C with aeration, diluted 200-fold in fresh medium, and regrown to mid-log phase (OD600, 0.5). Cells were processed and inoculated into a custom-made microfluidic device comprising a glass coverslip, semipermeable membrane, and micropatterned polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) chip (39). Silicon tubing was connected to the inlet and outlet ports of the PDMS chip, and medium was pumped through the chip at a rate of 25 μl/min. Phase and fluorescence images were recorded using a DeltaVision RT imaging system (Applied Precision) equipped with a ×100 oil immersion objective (Olympus Plan Semi Apochromat; numerical aperture, 1.3). In a typical experiment, images were captured from 40 to 60 xy fields at 1- or 2-h intervals (M. tuberculosis) or 10 to 20 xy points at 2-min intervals (uropathogenic E. coli) using a CoolSnap HQ2 camera and Softworx software (Applied Precision). Out-of-focus images were excluded from analysis.

Cell membrane potential.

M. tuberculosis cells were grown and exposed to isoniazid (0.5 μg/ml) for 10 days in a microfluidic device as described above. After drug washout, the membrane potential of the cells was detected by staining with 3 μM 3,3′-diethyloxacarbocyanine iodide dye (DiOC2; Invitrogen) for 1 to 2 h. Images were then recorded on the fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) and Texas Red channels. Image analysis was performed using standard ImageJ software functions.

Image analysis.

A custom-made macro of ImageJ software was used to analyze time-lapse image stacks (39). The macro draws an outline around individual cells, and measurements are made on the resulting polygon. Image stacks were processed sequentially, and time course changes of parameters were measured. To calculate the single-cell growth rates plotted in Fig. 4 and Fig. 5, the cell size plots during the time periods indicated below were fitted with exponential curves; cells that underwent division during the respective time windows were excluded. The survival curves depicted in Fig. 6 were generated by tracking cell division and lysis events over the course of antibiotic exposure using the Cell Counter plug-in of ImageJ software. For estimation of decay rates (kfast and kslow), the survival curves were fitted to a two-phase decay exponential equation using GraphPad Prism software, with the constraint that kfast should be at least 1.5 times greater than kslow.

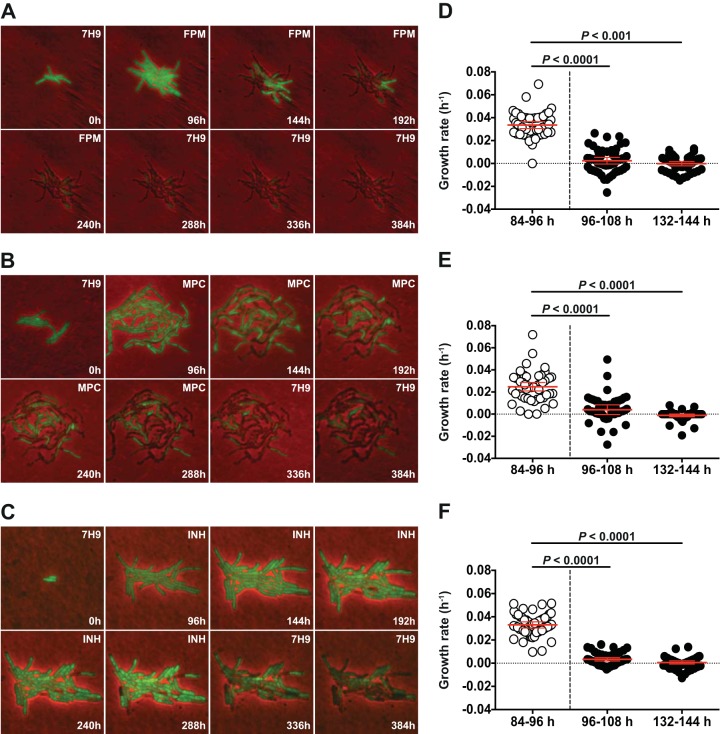

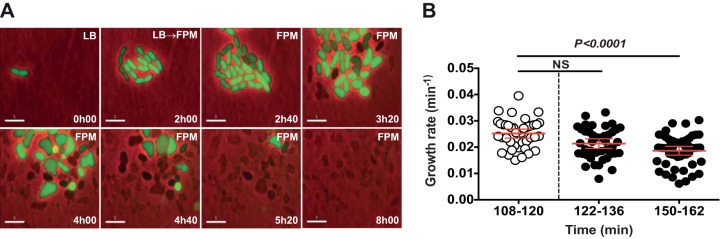

FIG 4.

Real-time single-cell analysis of faropenem-mediated growth inhibition. An M. tuberculosis strain expressing GFP was cultured in a microfluidic device under a constant flow of 7H9 medium and imaged at 1-h intervals. (A and D) Faropenem (28 μg/ml; ∼21× MIC) was added to the flow medium at 96 to 264 h. (B and E) Meropenem plus clavulanate (MPC; 8 μg/ml and 2.5 μg/ml, respectively; ∼26× MIC) was added to the flow medium at 96 to 330 h. (C and F) Isoniazid (0.5 μg/ml; ∼20× MIC) was added to the flow medium at 96 to 340 h. (A to C) Images were recorded on fluorescence (green) and phase channels and merged. Numbers (lower right) indicate the elapsed times (in hours). Labels (upper right) indicate the presence or absence of antibiotic in the flow medium. (D to F) Single-cell growth rates were determined by measuring the projected areas of single cells (n = 50) during the indicated time intervals and fitting exponential curves to the data.

FIG 5.

Real-time single-cell analysis of faropenem-mediated cytolysis of uropathogenic E. coli. Uropathogenic E. coli CFT073 expressing YFP was cultured in a microfluidic device under a constant flow of LB medium and imaged at 2-min intervals. Faropenem (4 μg/ml; ∼20× MIC) was added to the flow medium at 2 to 8 h. (A) Images were recorded on the fluorescence (green) and phase channels and merged. Numbers (lower right) indicate the elapsed times (in hours). Labels (upper right) indicate the flow medium. Scale bars, 5 µm. (B) Single-cell growth rates were determined by measuring the projected areas of single cells (n = 50) during the indicated time intervals and fitting exponential curves to the data. NS, no significant difference.

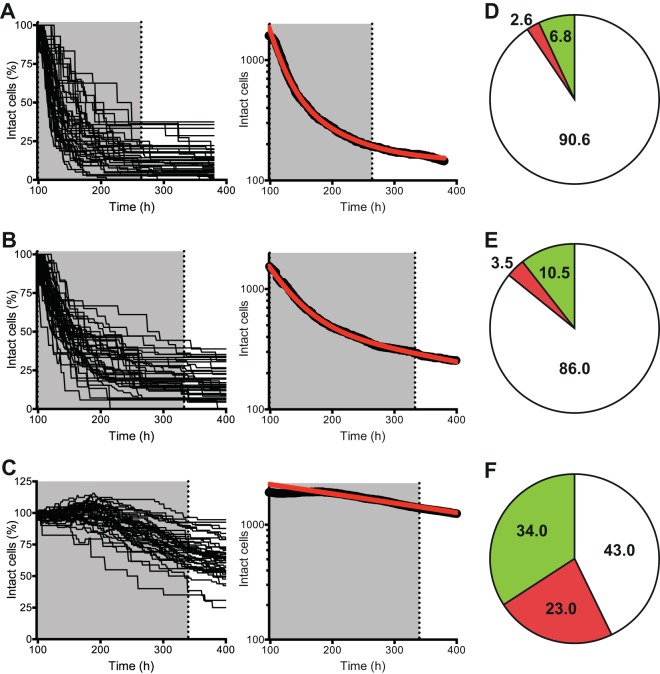

FIG 6.

Real-time single-cell analysis of faropenem-mediated cytolysis. An M. tuberculosis strain expressing GFP was cultured in a microfluidic device under a constant flow of 7H9 medium and imaged at 1-h intervals. (A and D) Faropenem (28 μg/ml; ∼21× MIC) was added to the flow medium at 96 to 264 h. (B and E) Meropenem plus clavulanate (8 μg/ml and 2.5 μg/ml, respectively; ∼26× MIC) was added to the flow medium at 96 to 330 h. (C and F) Isoniazid (0.5 μg/ml; ∼20× MIC) was added to the flow medium at 96 to 340 h. Cytolysis was scored visually as an abrupt loss of GFP fluorescence and an abrupt decrease in phase intensity. As an endpoint assay, 1.0 μg/ml PI was added to the flow medium for 24 h to stain cells with permeabilized cell envelopes. (A to C) Number of intact cells plotted for individual (left) and ensemble (right) microcolonies exposed to faropenem (n = 1,593 cells in 50 microcolonies) (A), meropenem plus clavulanate (n = 1,541 cells in 65 microcolonies) (B), or isoniazid (n = 1,917 cells in 41 microcolonies) (C). Shading, the interval of antibiotic exposure; red lines, curve fitting of the data using a two-phase decay exponential equation. (D to F) Percentage of single cells scored in three categories: lysed (white), intact but PI positive (red), and intact and PI negative (green).

Statistics.

Statistical analysis and fitting of data were performed using Prism software (GraphPad). For comparisons of cell growth rates, P values were determined using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov nonparametric t test (see Fig. 4 and 5). For comparison of cell lysis curves, the log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test was used (see Fig. 6A to C).

RESULTS

Faropenem efficiently inactivates M. tuberculosis l,d-transpeptidases.

We determined the MIC of faropenem against M. tuberculosis to be 1.3 μg/ml with or without clavulanate (Table 1). In contrast, omission of clavulanate increased the MICs of the other β-lactams that we tested, including meropenem (8-fold), ampicillin (≥16-fold), and amoxicillin (≥32-fold) (Table 1). The excellent activity of faropenem in the absence of clavulanate suggests that this antibiotic may not be an efficient substrate of β-lactamase. Alternatively, faropenem may inactivate its target more rapidly than other β-lactams, thereby limiting its exposure to β-lactamases. These possibilities were investigated by analyzing the interaction of faropenem with the M. tuberculosis β-lactamase BlaC and with the target enzymes, l,d-transpeptidases, which generate 3 → 3 cross-links in the peptidoglycan layer of the cell wall (25, 26, 32).

TABLE 1.

MICs against Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv

| Antibiotic | MIC (μg/ml) at the following clavulanate concn (μg/ml)a: |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 2.5 | 5 | |

| Faropenem | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 |

| Meropenem | 2.5 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| Imipenem | 2.5 | 0.5 | 0.3 |

| Amoxicillin | 40 | 1.3 | 0.9 |

| Ampicillin | >80 | 5 | 5 |

| Ethambutol | 2.5 | 1.25 | 1.25 |

| Moxifloxacin | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| Isoniazid | 0.025 | 0.038 | 0.025 |

| Rifampin | 0.004 | 0.003 | 0.003 |

The MIC for potassium clavulanate alone is >5 μg/ml.

M. tuberculosis produces five l,d-transpeptidase paralogues (25, 26). Kinetic analyses of l,d-transpeptidase inactivation by faropenem was studied in detail for LdtMt1, the prototypic l,d-transpeptidase from M. tuberculosis. Faropenem inactivated LdtMt1 14-fold more efficiently than meropenem, as deduced from comparison of kinact-to-Kapp ratios (Fig. 1A and C). Acylated adducts of LdtMt1 were identified by mass spectrometry (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). The mass increment observed after acylation of LdtMt1 by meropenem matched the exact mass of the antibiotic, indicating that a thioester bond is formed to the detriment of β-lactam ring opening (32). The mass of the LdtMt1-faropenem adduct was consistent with thioester bond formation and additional rupture of the C-5—C-6 bond. Both acyl enzymes were stable (Fig. 1B and C), although a 4-fold higher first-order rate constant for acyl enzyme hydrolysis (khydrol) was observed with faropenem (4.4 × 10−3 ± 0.1 × 10−3 min−1) than with meropenem (1.0 × 10−3 ± 0.1 × 10−3 min−1). Hydrolysis in the absence of enzyme was not detected for faropenem, whereas meropenem underwent slow spontaneous hydrolysis. These results show that faropenem inactivates LdtMt1 more rapidly than meropenem, mainly due to a more favorable catalytic constant for the chemical step of the acylation reaction (higher kinact; Fig. 1C). Comparison of inactivation of the other l,d-transpeptidases by meropenem and faropenem revealed that the latter drug was also more efficient for inactivation of LdtMt2 (22-fold), LdtMt3 (6-fold), and LdtMt4 (9-fold) (Table 2). All acyl enzymes were stable, although the rate constants were slightly higher for faropenem for all l,d-transpeptidases except LdtMt4. LdtMt5 was not acylated by meropenem or faropenem.

TABLE 2.

Kinetic constants for inactivation of LdtMt1 to LdtMt5 by β-lactamsa

| Enzyme |

kinact/Kapp (μM−1 min−1 [103]) |

khydrol (min−1 [103]) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meropenem | Faropenem | Meropenem | Faropenem | |

| LdtMt1 | 42 ± 10 | 590 ± 170 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 4.4 ± 0.1 |

| LdtMt2 | 0.5 ± 0.02 | 11 ± 0.3 | 0.7 ± 0.03 | 2.9 ± 0.1 |

| LdtMt3 | 10.9 ± 0.8 | 61 ± 3.9 | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 3.6 ± 0.2 |

| LdtMt4 | 4.8 ± 0.3 | 44 ± 3.3 | 5.6 ± 0.6 | 1.1 ± 0.5 |

| LdtMt5 | ND | ND | NA | NA |

NA, not applicable; ND, acylation not detected.

Meropenem was hydrolyzed by M. tuberculosis β-lactamase (BlaC) with a low catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km = 2.0 × 104 ± 0.5 × 104 M−1 min−1), which mainly resulted from the low efficiency of the chemical step of the reaction (kcat = 0.020 ± 0.001 min−1), since the value of Km (1.0 ± 0.2 μM) was low (Fig. 1D and F). In comparison, the hydrolysis of ampicillin by BlaC was 1,100-fold more efficient (kcat/Km = 2.2 × 107 ± 0.4 × 107 M−1 min−1), with the Km value being 12-fold higher (12 ± 2 μM) but the kcat value being 13,500-fold higher (270 ± 20 min−1) than the values for meropenem. BlaC hydrolyzed faropenem 2-fold more efficiently than meropenem (kcat/Km = 4.0 × 104 ± 0.5 × 104 M−1 min−1); the 23-fold higher Km for faropenem (23 ± 3 μM) was largely compensated for by a 45-fold higher kcat value (0.91 ± 0.03) (Fig. 1E and F).

The efficiency of β-lactams against M. tuberculosis is expected to depend on the relative velocities of target inactivation and BlaC-mediated hydrolysis, since these two reactions occur in competition. Meropenem and faropenem were both slowly hydrolyzed by BlaC, due to a low kcat for meropenem and a high Km for faropenem (Fig. 1E and F). In contrast, l,d-transpeptidases were inactivated 6- to 22-fold more rapidly by faropenem than by meropenem (Fig. 1A and C). Thus, rapid inactivation of l,d-transpeptidases by faropenem limits exposure of this drug to β-lactamase and accounts for the optimal antibacterial activity in the absence of clavulanate (Fig. 2A).

Faropenem exhibits antimycobacterial activity in vitro and in macrophages.

Faropenem and meropenem were further compared for their activity against M. tuberculosis bacilli in vitro. Faropenem efficiently killed M. tuberculosis, giving a 105- to 106-fold reduction in the number of CFU over 6 days of exposure at the highest doses that we tested (Fig. 2B). While faropenem inhibited mycobacterial growth at 1.3 μg/ml (MIC90; Fig. 2A), it exhibited bactericidal activity only at concentrations above 4 μg/ml (Fig. 2B). We also compared the kinetics of killing by a single dose of faropenem (8 μg/ml; ∼6× MIC), meropenem (8 μg/ml; ∼3× MIC), or meropenem plus clavulanate (8 μg/ml and 2.5 μg/ml, respectively; ∼26× MIC). A single dose of meropenem reduced the number of bacterial CFU only during the first 2 days of exposure (Fig. 2C). The observed rebound in the number of CFU at later time points presumably reflects the short half-life of meropenem in Middlebrook 7H9 medium (15) (Fig. 2D) and its inactivation by β-lactamase. In contrast, a single dose of faropenem gave sustained killing over 8 days, which was further enhanced by increasing the dose to 28 μg/ml (∼21× MIC) (Fig. 2C). Clavulanate modestly enhanced early killing by meropenem but had no effect on faropenem activity (Fig. 2C). The level of killing of M. tuberculosis by the combination of meropenem plus clavulanate was lower than that reported in previous studies (12, 13). However, it should be noted that in the experiment whose results are shown in Fig. 2C, the compounds were dosed only once, on day 0, whereas in previous studies the compounds were dosed every day.

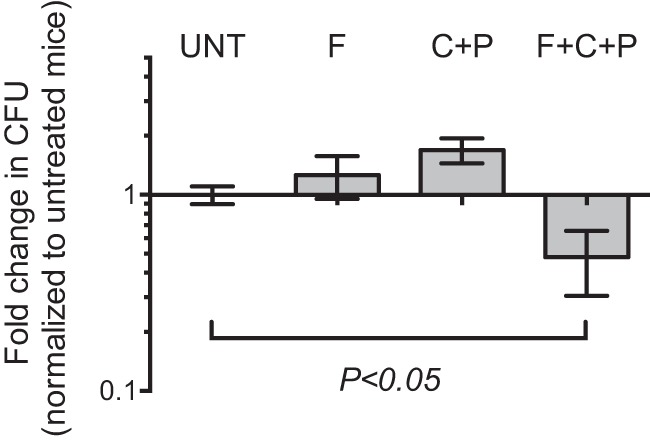

Against intracellular M. tuberculosis, faropenem was similar to meropenem-clavulanate in its ability to suppress bacterial proliferation (Fig. 2E) and reduce the fraction of infected macrophages detected by flow cytometry (Fig. 2F). Similar effects were observed at lower concentrations of the compounds (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). Evaluation of β-lactams in rodent models is problematic due to the rapid inactivation of β-lactams by the enzyme dehydropeptidase (DPEP1). Despite this limitation, we attempted to evaluate the efficacy of faropenem in vivo using a short therapeutic-efficacy assay in mice (37). Mice infected with M. tuberculosis were treated with faropenem given alone or in combination with clavulanate and probenecid (a dehydropeptidase inhibitor) from days 1 to 7 postinfection. Determination of bacterial loads on day 9 revealed a modest but significant reduction in the bacterial load only in the case of mice that had been treated with the combination of faropenem, clavulanate, and probenecid (P < 0.05, Mann-Whitney test). This reduction in bacterial load was comparable to the decrease observed in previous studies evaluating β-lactams against M. tuberculosis in the mouse model (14, 15, 40) (Fig. 3; Table 3).

FIG 3.

Efficacy of faropenem in a mouse model of tuberculosis. C57BL/6J mice infected with M. tuberculosis were treated with 500 mg/kg faropenem medoxomil (F), 25 mg/kg clavulanate plus 200 mg/kg probenecid (C+P), or 500 mg/kg faropenem medoxomil plus 25 mg/kg clavulanate and 200 mg/kg probenecid (F+C+P) on days 1 to 8 postinfection. The bacterial loads in lungs harvested on day 9 were determined, and the fold change in the number of CFU relative to the number of CFU for the untreated controls (UNT) is depicted. Results are means ± SEMs for five mice in each group. *, P < 0.05, Mann-Whitney test.

TABLE 3.

Pharmacokinetic parameters of faropenem in micea

| Compound(s) | Tmax (h) | Cmax (μg/ml) | AUC (μg · h/ml) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Faropenem | 0.25 | 69.6 ± 16.1 | 65.9 ± 19.1 |

| Faropenem and probenecid | 0.25 | 83.8 ± 13.4 | 126.2 ± 20.5 |

| Faropenem, probenecid, and clavulanate | 0.25 | 83.1 ± 15.6 | 107.1 ± 38.7 |

Pharmacokinetic parameters of faropenem in mice after oral administration of a single dose of faropenem, faropenem plus probenecid, or faropenem plus probenecid and lithium clavulanate. Data represent means ± standard deviations. Tmax, time to the maximum concentration; Cmax, maximum concentration; AUC, area under the concentration-time curve.

Real-time single-cell analysis of faropenem-mediated growth inhibition and killing.

Recently, we described an assay using custom-made microfluidics and automated time-lapse fluorescence microscopy for real-time single-cell analysis of antibiotic-mediated killing and persistence in the model organism Mycobacterium smegmatis (39). Here, we adapted this technique to M. tuberculosis in order to visualize the antimycobacterial activity of β-lactams compared to that of isoniazid, a frontline anti-TB drug.

An M. tuberculosis strain expressing GFP was cultured under a continuous flow of 7H9 medium (no antibiotic) for 96 h. During this preantibiotic interval, individual cells grew and divided repeatedly to form clonal microcolonies (Fig. 4A to C). The flow medium was then switched to 7H9 containing faropenem (Fig. 4A and D; see Movie S1 in the supplemental material), meropenem plus clavulanate (Fig. 4B and E; see Movie S2 in the supplemental material), or isoniazid (Fig. 4C and F; see Movie S3 in the supplemental material). We measured the growth rates of individual M. tuberculosis cells before addition of compound to the flow medium and during the initial (0 to 12 h) and later (36 to 48 h) phases of drug exposure. Unexpectedly, we observed that all three antibiotics induced a rapid and sustained arrest of the growth of single cells (Fig. 4D to F), followed by cytolysis after a variable lag period (Fig. 4A to C; see Movies S1 to S3 in the supplemental material). This response contrasts sharply with the impact of β-lactams on single cells of Escherichia coli, which continued to grow in the presence of the antibiotic up to the time that they underwent cytolysis (41) (Fig. 5; see Movie S4 in the supplemental material).

Faropenem reduces a subpopulation of nongrowing metabolically active cells.

Automated time-lapse microscopy permits the dynamic tracking of single-cell growth, division, and death at high temporal resolution during a pulsed exposure to an antimicrobial compound (39). We found that microfluidic cultures of M. tuberculosis exhibited biphasic kinetics of single-cell cytolysis by faropenem (Fig. 6A), meropenem-clavulanate (Fig. 6B), or isoniazid (Fig. 6C). During the initial killing phase of the kill curve, the rate of cytolysis by faropenem (kfast, ∼0.049 h−1) was about 2-fold higher than that of meropenem-clavulanate (kfast, ∼0.024 h−1) and about 20-fold higher than that of isoniazid (kfast, ∼0.0026 h−1). During the persistence phase of the kill curve, the rate of cytolysis was lower but remained higher for faropenem (kslow, ∼0.014 h−1) than meropenem-clavulanate (kslow, ∼0.0022 h−1) or isoniazid (kslow, ∼0.0017 h−1). Faropenem (Fig. 6A and D) was superior to either meropenem (Fig. 6B and E) or isoniazid (Fig. 6C and F) with respect to the speed of cytolysis (P < 0.0001, log-rank Mantel-Cox test). In terms of the fraction of cells lysed, both faropenem and meropenem killed a larger fraction of cells than isoniazid (P < 0.0001, Mann-Whitney test). These differences cannot be ascribed to differential compound stabilities because the continuous-flow design of our microfluidic devices ensures that the medium bathing the bacteria is constantly and rapidly refreshed, as confirmed by pulse-chase analysis of fluorescent tracer dyes injected into the flow medium.

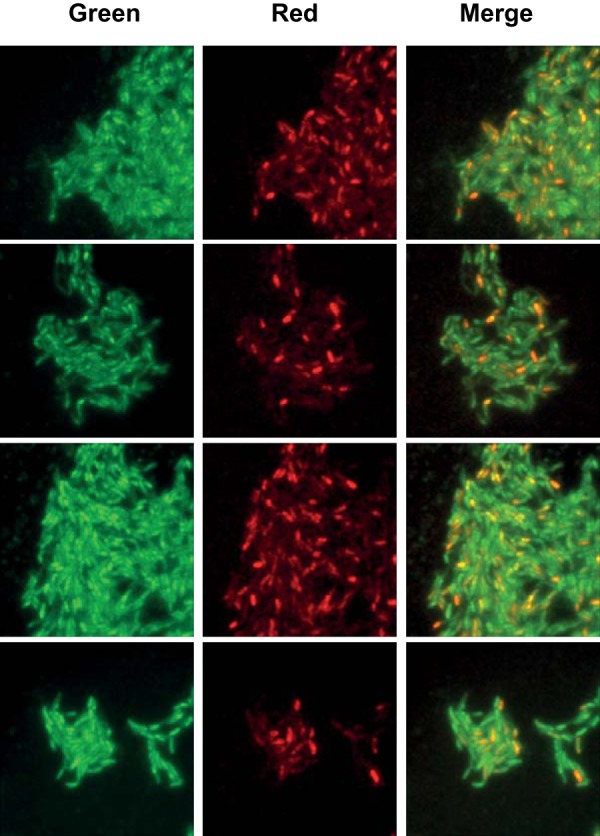

During the postantibiotic interval of observation, the flow medium was switched to 7H9 (no antibiotic) to allow recovery and regrowth of surviving bacteria. At the end of this period, propidium iodide (PI), which selectively stains damaged (permeabilized) cells, was added to the flow medium for an additional 24 h as an endpoint assay. Reproducibly, 10 to 15% of microcolonies exposed to meropenem-clavulanate exhibited regrowth after antibiotic washout; in all cases, regrowth was attributable to a single individual within the microcolony. In contrast, none of the microcolonies exposed to faropenem or isoniazid exhibited regrowth after antibiotic washout. In each case, however, a fraction of cells that failed to regrow after antibiotic washout was intact and excluded PI (Fig. 6D to F), suggesting that these cells might be similar to previously described viable but nonculturable (VBNC) or nongrowing but metabolically active (NGMA) cells (29, 30). The fraction of intact and PI-negative cells was particularly high in isoniazid-exposed microcolonies (Fig. 6F), underscoring the superior cytolytic activity of faropenem (Fig. 6D). As a further metric of the physical integrity and metabolic activity of the cryptic population of intact but nonreplicating cells, we assessed the cell membrane potential of isoniazid-treated bacteria by staining with the fluorescent probe DiOC2 and imaging by fluorescence microscopy. Of the 57% of physically intact cells observed after prolonged INH exposure, about 25% were found to have an intact membrane potential, implying that cell membrane integrity and metabolic activity are maintained in this subpopulation (Fig. 7). These observations underscore the potential significance of this cryptic subpopulation of cells as a possible source of bacteriologic relapse following prolonged drug exposure, although final proof of their viability will hinge on the identification of conditions capable of reactivating their growth.

FIG 7.

Detection of membrane potential in single cells of isoniazid-treated M. tuberculosis. Bacteria were cultured in a microfluidic device under a constant flow of 7H9 medium. Medium conditions were as follows: t = 0 to 96 h, no antibiotic; t = 96 to 340 h, addition of isoniazid (0.5 μg/ml; 20× MIC); t = 340 to 400 h, no antibiotic. As an endpoint assay, 3 μM DiOC2 was added to the flow medium, and imaging was continued at 1-h intervals on the FITC and Texas Red fluorescence channels. Representative snapshots and the merged images from four random positions in the microfluidic device are shown in the four rows. In this assay, all cells exhibit green fluorescence, but higher cytosolic concentrations of the dye lead to self-association and a shift toward red fluorescence emission in cells with an intact membrane potential.

DISCUSSION

Detection and treatment of MDR-TB and XDR-TB is a serious and increasing burden on the public health infrastructure of many countries, including some of the world's poorest countries with the highest incidence of disease (1, 2). Although recent years have seen a resurgence of activity directed toward the discovery of novel chemical entities for the treatment of drug-resistant TB (3, 5), advancing new classes of compounds from preclinical studies into clinical use is an unavoidably slow and expensive process with a high failure rate (42, 43). Many experimental compounds fail at late stages of clinical development due to the recognition of unacceptable toxicity issues in humans. Therefore, repositioning of already established drugs with proven track records of safety in humans is an attractive alternative (6, 44).

Here, we present evidence to support the repositioning of faropenem, a β-lactam antibiotic that has already been approved for therapeutic use in patients with conditions other than tuberculosis. Although encouraging results have recently been obtained using meropenem for the treatment of XDR-TB in humans (18–20), the instability and poor bioavailability of this compound, which necessitate frequent or continuous intravenous administration, will likely restrict its broader clinical application. Faropenem is an orally bioavailable penem antibiotic that is more resistant to hydrolysis by β-lactamases than cephalosporins and carbapenems are (21–24). As demonstrated here, faropenem exhibits potent biochemical activity and inactivates M. tuberculosis l,d-transpeptidase enzymes more efficiently than meropenem. In contrast to meropenem, which requires supplementation with a β-lactamase inhibitor, the bactericidal activity of faropenem was found to be independent of clavulanate. Faropenem's stability, oral bioavailability, superior cytolytic activity, biochemical potency against its molecular target, and proven efficacy in the treatment of infections caused by nontuberculous mycobacteria (45, 46) all justify further investigation of this compound's potential in the chemotherapy of MDR-TB and XDR-TB.

Conventionally, preclinical evaluation of antituberculosis drugs includes proof of efficacy in animal models. However, the use of conventional animal models to obtain proof of in vivo efficacy for β-lactams is problematic due to rapid enzymatic hydrolysis by dehydropeptidase, which is more active in mice, rats, pigs, and rabbits than humans (17, 47, 48). This issue is exemplified by studies of meropenem, which has been successfully used for the treatment of human tuberculosis in clinical cases (18–20), despite exhibiting marginal bactericidal activity when tested in mice (15, 40). In the mouse model, we found that faropenem alone does not reduce bacterial loads in the lungs of treated mice compared to those in the lungs of untreated mice. Only when administered in combination with probenecid and clavulanate does faropenem give a small reduction in the pulmonary bacterial load that is similar to the activity observed for the combination of meropenem and clavulanate (15, 40). Administration of probenecid and clavulanate increases the maximum concentration (Cmax) and level of exposure to faropenem but does not increase the time to Cmax of the compound. Interestingly, although we found that β-lactams do not exhibit significant bactericidal activity against intracellular M. tuberculosis, the fraction of infected macrophages decreases over the course of treatment. This could reflect increased intracellular multiplication without dissemination to uninfected macrophages or, alternatively, a balance between actively replicating and dying intracellular subpopulations. While plating for determination of the numbers of CFU at defined time points cannot distinguish between these possibilities, it might be possible to resolve this issue in the future using single-cell time-lapse microscopy of infected macrophages.

The hurdle to launching clinical studies of faropenem against human tuberculosis should be low because this compound has already been approved for human use and its pharmacokinetics in humans are known (23, 24, 49, 50). Indeed, the data presented in this paper were the basis for the regulatory approval of a phase II clinical trial aimed at evaluating the efficacy of faropenem in patients with drug-resistant TB and performed under the auspices of the European and Developing Countries Clinical Trials Partnership. Proof that an orally bioavailable β-lactam antibiotic can be effective in treating human tuberculosis would provide an important precedent and justify further exploration of this class of antibiotics as an alternative therapy for drug-resistant and, potentially, drug-sensitive disease. As β-lactams have never been a component of the standard regimen for treatment of tuberculosis, preexisting bacterial resistance should not be a confounder. Also, β-lactams are potentially attractive candidates for further exploration, as large and diverse compound libraries representing this class of antibiotics already exist, as do other important resources for drug discovery, including high-resolution three-dimensional structures of mycobacterial transpeptidases (51, 52).

Conventionally, the impact of antimicrobials on bacteria has been evaluated using assay systems that rely on population-averaged measurements, which provide little insight into the behavior of individual cells and phenotypic variants, such as rare persister cells that are refractory to killing (53). Most conventional assays also rely on cellular multiplication for enumeration of surviving cells, which precludes identification of NGMA variants that might be responsible for relapses following apparently curative chemotherapy (28–30). Here, we describe a real-time single-cell assay system based on microfluidics and time-lapse microscopy that overcomes both of these limitations of traditional bacteriologic assays. We use this system to show that faropenem is more efficient than isoniazid in inducing M. tuberculosis cytolysis and eliminating a subpopulation of NGMA bacteria, a distinction that could not be made using conventional bacteriologic assays.

Our microfluidics/microscopy-based assay system also provides novel insights into the dynamics of single-cell behavior under antibiotic exposure conditions, which is relevant for understanding the mechanism of action of antimicrobials. For example, conventional assays do not reveal whether individual cells arrest growth in response to the antibiotic and then die or, alternatively, continue to grow and divide in the presence of the antibiotic up to the time of cell death. It has been proposed that β-lactams kill bacteria by preventing cross-linking of newly synthesized peptidoglycan without arresting cell growth, resulting in progressive weakening of the cell wall and cytolysis due to turgor pressure (41, 54). Consistent with this interpretation, we found that cells of uropathogenic E. coli exposed to faropenem continue to grow rapidly up to the time of cytolysis. In marked contrast, we found that exposure of M. tuberculosis to faropenem causes immediate growth arrest, while cytolysis commences only after a lengthy delay, during which there is no detectable growth. These observations suggest that the conventional explanation for the mechanism of killing by β-lactams is probably not correct in the case of M. tuberculosis. Clearly, there is still much to learn about the intricacies of antibiotic-mediated killing and persistence, even for compound classes that have been as extensively studied as the β-lactams.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge Joaquín Rullas and Inigo Angulo (DDW, GlaxoSmithKline) for the design and implementation of the in vivo efficacy experiment and Andreas Diacon (Stellenbosch University) for critical feedback on the manuscript.

V.D. is the recipient of a fellowship from the Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale (Poste d'Accueil pour Pharmacien, Médecin, et Vétérinaire). This research was funded in part by grants from European Commission Seventh Framework Programme ORCHID project no. 261378 (to D.B., M.A., and J.D.M.), the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (to J.D.M.), and Swiss National Science Foundation grant no. 138869 (to J.D.M.).

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AAC.03461-14.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. 2012. Global tuberculosis report 2012. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gandhi NR, Nunn P, Dheda K, Schaaf HS, Zignol M, van Soolingen D, Jensen P, Bayona J. 2010. Multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis: a threat to global control of tuberculosis. Lancet 375:1830–1843. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60410-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koul A, Arnoult E, Lounis N, Guillemont J, Andries K. 2011. The challenge of new drug discovery for tuberculosis. Nature 469:483–490. doi: 10.1038/nature09657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palomino JC, Martin A. 2013. Is repositioning of drugs a viable alternative in the treatment of tuberculosis? J Antimicrob Chemother 68:275–283. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zumla A, Nahid P, Cole ST. 2013. Advances in the development of new tuberculosis drugs and treatment regimens. Nat Rev Drug Discov 12:388–404. doi: 10.1038/nrd4001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ashburn TT, Thor KB. 2004. Drug repositioning: identifying and developing new uses for existing drugs. Nat Rev Drug Discov 3:673–683. doi: 10.1038/nrd1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hamad B. 2010. The antibiotics market. Nat Rev Drug Discov 9:675–676. doi: 10.1038/nrd3267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Papp-Wallace KM, Endimiani A, Taracila MA, Bonomo RA. 2011. Carbapenems: past, present, and future. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:4943–4960. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00296-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Biondi S, Long S, Panunzio M, Qin WL. 2011. Current trends in beta-lactam based beta-lactamases inhibitors. Curr Med Chem 18:4223–4236. doi: 10.2174/092986711797189655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flores AR, Parsons LM, Pavelka MS Jr. 2005. Genetic analysis of the beta-lactamases of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium smegmatis and susceptibility to beta-lactam antibiotics. Microbiology 151:521–532. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27629-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hugonnet JE, Blanchard JS. 2007. Irreversible inhibition of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis beta-lactamase by clavulanate. Biochemistry 46:11998–12004. doi: 10.1021/bi701506h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hugonnet JE, Tremblay LW, Boshoff HI, Barry CE III, Blanchard JS. 2009. Meropenem-clavulanate is effective against extensively drug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Science 323:1215–1218. doi: 10.1126/science.1167498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kumar P, Arora K, Lloyd JR, Lee IY, Nair V, Fischer E, Boshoff HI, Barry CE III. 2012. Meropenem inhibits d,d-carboxypeptidase activity in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol Microbiol 86:367–381. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08199.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chambers HF, Turner J, Schecter GF, Kawamura M, Hopewell PC. 2005. Imipenem for treatment of tuberculosis in mice and humans. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 49:2816–2821. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.7.2816-2821.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.England K, Boshoff HI, Arora K, Weiner D, Dayao E, Schimel D, Via LE, Barry CE III. 2012. Meropenem-clavulanic acid shows activity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis in vivo. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:3384–3387. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05690-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Veziris N, Truffot C, Mainardi JL, Jarlier V. 2011. Activity of carbapenems combined with clavulanate against murine tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:2597–2600. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01824-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fukasawa M, Sumita Y, Harabe ET, Tanio T, Nouda H, Kohzuki T, Okuda T, Matsumura H, Sunagawa M. 1992. Stability of meropenem and effect of 1 beta-methyl substitution on its stability in the presence of renal dehydropeptidase I. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 36:1577–1579. doi: 10.1128/AAC.36.7.1577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dauby N, Muylle I, Mouchet F, Sergysels R, Payen MC. 2011. Meropenem/clavulanate and linezolid treatment for extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis. Pediatr Infect Dis J 30:812–813. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3182154b05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Lorenzo S, Alffenaar JW, Sotgiu G, Centis R, D'Ambrosio L, Tiberi S, Bolhuis MS, van Altena R, Viggiani P, Piana A, Spanevello A, Migliori GB. 2013. Efficacy and safety of meropenem-clavulanate added to linezolid-containing regimens in the treatment of MDR-/XDR-TB. Eur Respir J 41:1386–1392. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00124312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Payen MC, De Wit S, Martin C, Sergysels R, Muylle I, Van Laethem Y, Clumeck N. 2012. Clinical use of the meropenem-clavulanate combination for extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 16:558–560. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.11.0414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mushtaq S, Hope R, Warner M, Livermore DM. 2007. Activity of faropenem against cephalosporin-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. J Antimicrob Chemother 59:1025–1030. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dalhoff A, Nasu T, Okamoto K. 2003. Beta-lactamase stability of faropenem. Chemotherapy 49:229–236. doi: 10.1159/000072446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gettig JP, Crank CW, Philbrick AH. 2008. Faropenem medoxomil. Ann Pharmacother 42:80–90. doi: 10.1345/aph.1G232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schurek KN, Wiebe R, Karlowsky JA, Rubinstein E, Hoban DJ, Zhanel GG. 2007. Faropenem: review of a new oral penem. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 5:185–198. doi: 10.1586/14787210.5.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lavollay M, Arthur M, Fourgeaud M, Dubost L, Marie A, Veziris N, Blanot D, Gutmann L, Mainardi JL. 2008. The peptidoglycan of stationary-phase Mycobacterium tuberculosis predominantly contains cross-links generated by l,d-transpeptidation. J Bacteriol 190:4360–4366. doi: 10.1128/JB.00239-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cordillot M, Dubee V, Triboulet S, Dubost L, Marie A, Hugonnet JE, Arthur M, Mainardi JL. 2013. In vitro cross-linking of Mycobacterium tuberculosis peptidoglycan by l,d-transpeptidases and inactivation of these enzymes by carbapenems. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:5940–5945. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01663-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Flores AR, Parsons LM, Pavelka MS Jr. 2005. Characterization of novel Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium smegmatis mutants hypersusceptible to beta-lactam antibiotics. J Bacteriol 187:1892–1900. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.6.1892-1900.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McCune RM, Feldmann FM, Lambert HP, McDermott W. 1966. Microbial persistence. I. The capacity of tubercle bacilli to survive sterilization in mouse tissues. J Exp Med 123:445–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manina G, McKinney JD. 2013. A single-cell perspective on non-growing but metabolically active (NGMA) bacteria. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 374:135–161. doi: 10.1007/82_2013_333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Manina G, Dhar N, McKinney JD. Stress and host immunity amplify M. tuberculosis heterogeneity and induce non-growing metabolically active forms. Cell Host Microbe, in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sharma S, Gelman E, Narayan C, Bhattacharjee D, Achar V, Humnabadkar V, Balasubramanian V, Ramachandran V, Dhar N, Dinesh N. 2014. Simple and rapid method to determine antimycobacterial potency of compounds by using autoluminescent Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:5801–5808. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03205-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dubee V, Triboulet S, Mainardi JL, Etheve-Quelquejeu M, Gutmann L, Marie A, Dubost L, Hugonnet JE, Arthur M. 2012. Inactivation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis l,d-transpeptidase LdtMt(1) by carbapenems and cephalosporins. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:4189–4195. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00665-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Soroka D, Dubee V, Soulier-Escrihuela O, Cuinet G, Hugonnet JE, Gutmann L, Mainardi JL, Arthur M. 2014. Characterization of broad-spectrum Mycobacterium abscessus class A beta-lactamase. J Antimicrob Chemother 69:691–696. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mainardi JL, Hugonnet JE, Rusconi F, Fourgeaud M, Dubost L, Moumi AN, Delfosse V, Mayer C, Gutmann L, Rice LB, Arthur M. 2007. Unexpected inhibition of peptidoglycan ld-transpeptidase from Enterococcus faecium by the beta-lactam imipenem. J Biol Chem 282:30414–30422. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704286200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Triboulet S, Arthur M, Mainardi JL, Veckerle C, Dubee V, Nguekam-Moumi A, Gutmann L, Rice LB, Hugonnet JE. 2011. Inactivation kinetics of a new target of beta-lactam antibiotics. J Biol Chem 286:22777–22784. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.239988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Triboulet S, Dubee V, Lecoq L, Bougault C, Mainardi JL, Rice LB, Etheve-Quelquejeu M, Gutmann L, Marie A, Dubost L, Hugonnet JE, Simorre JP, Arthur M. 2013. Kinetic features of l,d-transpeptidase inactivation critical for beta-lactam antibacterial activity. PLoS One 8:e67831. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rullas J, Garcia JI, Beltran M, Cardona PJ, Caceres N, Garcia-Bustos JF, Angulo-Barturen I. 2010. Fast standardized therapeutic-efficacy assay for drug discovery against tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 54:2262–2264. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01423-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lutz R, Bujard H. 1997. Independent and tight regulation of transcriptional units in Escherichia coli via the LacR/O, the TetR/O and AraC/I1-I2 regulatory elements. Nucleic Acids Res 25:1203–1210. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.6.1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wakamoto Y, Dhar N, Chait R, Schneider K, Signorino-Gelo F, Leibler S, McKinney JD. 2013. Dynamic persistence of antibiotic-stressed mycobacteria. Science 339:91–95. doi: 10.1126/science.1229858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Solapure S, Dinesh N, Shandil R, Ramachandran V, Sharma S, Bhattacharjee D, Ganguly S, Reddy J, Ahuja V, Panduga V, Parab M, Vishwas KG, Kumar N, Balganesh M, Balasubramanian V. 2013. In vitro and in vivo efficacy of beta-lactams against replicating and slowly growing/nonreplicating Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:2506–2510. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00023-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yao Z, Kahne D, Kishony R. 2012. Distinct single-cell morphological dynamics under beta-lactam antibiotics. Mol Cell 48:705–712. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Anonymous. 2010. The antibacterial lead discovery challenge. Nat Rev Drug Discov 9:751–752. doi: 10.1038/nrd3289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Payne DJ, Gwynn MN, Holmes DJ, Pompliano DL. 2007. Drugs for bad bugs: confronting the challenges of antibacterial discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov 6:29–40. doi: 10.1038/nrd2201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Paul SM, Lewis-Hall F. 2013. Drugs in search of diseases. Sci Transl Med 5:186fs118. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tanaka E, Kimoto T, Tsuyuguchi K, Suzuki K, Amitani R. 2002. Successful treatment with faropenem and clarithromycin of pulmonary Mycobacterium abscessus infection. J Infect Chemother 8:252–255. doi: 10.1007/s10156-002-0176-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Morihara K, Takenaka H, Morihara T, Katoh N. 2011. Cutaneous Mycobacterium chelonae infection successfully treated with faropenem. J Dermatol 38:211–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2010.00970.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hikida M, Kawashima K, Yoshida M, Mitsuhashi S. 1992. Inactivation of new carbapenem antibiotics by dehydropeptidase-I from porcine and human renal cortex. J Antimicrob Chemother 30:129–134. doi: 10.1093/jac/30.2.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Moon YS, Chung KC, Gill MA. 1997. Pharmacokinetics of meropenem in animals, healthy volunteers, and patients. Clin Infect Dis 24(Suppl 2):S249–S255. doi: 10.1093/clinids/24.Supplement_2.S249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hamilton-Miller JM. 2003. Chemical and microbiologic aspects of penems, a distinct class of beta-lactams: focus on faropenem. Pharmacotherapy 23:1497–1507. doi: 10.1592/phco.23.14.1497.31937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sorbera LA, Del Fresno M, Castaner RM, Rabasseda X. 2002. Faropenem daloxate: penem antibiotic. Drugs Future 27:223–233. doi: 10.1358/dof.2002.027.03.659134. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Erdemli SB, Gupta R, Bishai WR, Lamichhane G, Amzel LM, Bianchet MA. 2012. Targeting the cell wall of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: structure and mechanism of l,d-transpeptidase 2. Structure 20:2103–2115. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2012.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Correale S, Ruggiero A, Capparelli R, Pedone E, Berisio R. 2013. Structures of free and inhibited forms of the l,d-transpeptidase LdtMt1 from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 69:1697–1706. doi: 10.1107/S0907444913013085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dhar N, McKinney JD. 2007. Microbial phenotypic heterogeneity and antibiotic tolerance. Curr Opin Microbiol 10:30–38. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2006.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tomasz A. 1979. The mechanism of the irreversible antimicrobial effects of penicillins: how the beta-lactam antibiotics kill and lyse bacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol 33:113–137. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.33.100179.000553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.