Abstract

Emerging resistance to antimalarial agents raises the need for new drugs. ACT-451840 is a new compound with potent activity against sensitive and resistant Plasmodium falciparum strains. This was a first-in-humans single-ascending-dose study to investigate the safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of ACT-451840 across doses of 10, 50, 200, and 500 mg in healthy male subjects. In the 200- and 500-mg dose groups, the effect of food was investigated, and antimalarial activity was assessed using an ex vivo bioassay with P. falciparum. No (serious) adverse events leading to discontinuation were reported. At the highest dose level, the peak drug concentration (Cmax) and the area under the plasma concentration-time curve from zero to infinity of ACT-451840 under fasted conditions reached 11.9 ng/ml and 100.6 ng · h/ml, respectively, and these were approximately 13-fold higher under fed conditions. Food did not affect the half-life (approximately 34 h) of the drug, while the Cmax was attained 2.0 and 3.5 h postdose under fasted and fed conditions, respectively. The plasma concentrations estimated by the bioassay were approximately 4-fold higher than those measured by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). Several potentially active metabolites were also identified. ACT-451840 was well tolerated across all doses. Exposure to ACT-451840 significantly increased with food. The bioassay indicated the presence of circulating active metabolites. (This study has been registered at ClinicalTrials.gov under registration no. NCT02186002.)

INTRODUCTION

Malaria is a disease caused by a protozoan transmitted by the bite of the Anopheles mosquito. Among the five species that can infect humans, Plasmodium falciparum is responsible for the most severe form of malaria in humans. Malaria is present in 109 countries (1). Every year, 660,000 people suffer from malaria (range, 490,000 to 836,000), and it is newly diagnosed in 219 million (range, 154 to 289 million) people across the world (2). Also, in 2010, it was estimated that 57% of the African population was living in an area of moderate-to-high malarial transmission intensity (3). Despite the availability of effective antimalarial drugs, the prevention and treatment of malaria are progressively becoming more difficult due to the global spread of drug resistance (4, 5). Moreover, no new antimalarial chemical class has been registered since 1996 (6). Recently, a new chemical class of antimalarial piperazine-containing compounds has been identified, and the in vitro and in vivo development of one of the lead compounds of this chemotype have been described (7). This new class presents a different mode of action than artemisinin derivatives and could potentially be used as a substitute for these in combination with a compound with a longer half-life (7). ACT-451840 [(S,E)-N-(4-(4-acetylpiperazin-1-yl)benzyl)-3-(4-(tert-butyl)phenyl)-N-(1-(4-(4-cyanobenzyl)piperazin-1-yl)-1-oxo-3-phenylpropan-2-yl)acrylamide] is another compound from this new class. ACT-451840 is lipophilic, with a logD (octanol-phosphate buffer [pH 7.4]) of 5.2. Its solubility in fasted-state (7 μg/ml) is lower than that in fed-state (79 μg/ml) simulated intestinal fluid. In nonclinical studies, ACT-451840 has shown potent activity against sensitive and resistant P. falciparum strains. Similar to artemisinins, ACT-451840 targets all asexual blood stages of the parasite (rings, trophozoites, and schizonts), has a rapid onset of action, and shows efficacy in the Plasmodium berghei mouse model (8). ACT-451840 is also efficacious in the humanized P. falciparum mouse model and has a good safety profile (Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd., unpublished data). These properties make ACT-451840 a potential new chemical entity for investigation in humans. This first-in-humans study (registered at ClinicalTrials.gov under registration no. NCT02186002) was performed to investigate the safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics (PK), food effect, and ex vivo antimalarial activity of single ascending doses of this new compound in healthy male subjects.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects.

This study included 40 healthy male subjects, as assessed by medical history, physical examination, electrocardiogram (ECG), vital signs, and clinical laboratory tests. The subjects had to be between 18 and 45 years old, a nonsmoker for ≥3 months, and have a body mass index (BMI) from 18 to 28 kg/m2 at screening.

The Independent French Ethics Committee of South-East IV and the French National Authority for Health approved the study protocol. All subjects gave written informed consent before any screening procedures. The study was conducted in full conformity with the Declaration of Helsinki and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) Guideline for good clinical practice (9).

Study design.

This was a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, and single-ascending-dose phase 1 study with a nested one-way crossover group to assess food effect. The no-observed-adverse-effect level (NOAEL) of 100 mg/kg of body weight/day, determined in 4-week toxicology studies in rats and dogs, was based on body weight reduction and liver enzyme and bilirubin increases at higher doses. The NOAEL was converted to a human equivalent dose, in accordance with the FDA guideline (10), using body surface area to determine the safety margin. For the starting dose of 10 mg, the resulting safety margin from the NOAEL of the 4-week rat study was 111, whereas 500 mg was covered with a safety margin of 2.2. The safety margins based on the dog data were 4 times higher. Four groups of 8 subjects each (6 active and 2 placebo) were included: 10, 50, and 200 mg in a fasted state and 200 mg in a fed state. Another group of 8 subjects (6 active and 2 placebo) was included with the dose of 500 mg to assess the effect of food in a one-way crossover design in a fasted followed by a fed state, with a washout period of ≥7 days. The subjects had to enter the study center on day −1, were dosed in the fasted or in the fed state on the morning of day 1, and were observed for ≥4 days. ACT-451840 was administered as a suspension. The decision to proceed to the next higher dose level was taken based on a review of the blinded tolerability and PK data of the subjects receiving the preceding dose(s). The fasted state was defined as overnight fasting for 10 h before dosing and fed state as dosing within 30 min following the ingestion of a high-fat meal (approximately 800 to 1,000 cal, with 50% from fat) (11).

Safety and tolerability.

Safety and tolerability were evaluated by recording adverse events (AEs), clinical laboratory variables, vital signs, 12-lead ECGs, and physical examination results throughout the study. An end-of-study examination was performed after the last PK blood sampling. The arithmetic mean and median change from baseline were calculated for vital signs, ECG parameters, and clinical laboratory variables. In addition to the principal investigator, each ECG trace was reviewed by an external cardiologist.

Pharmacokinetic assessments.

The PK blood samples were drawn predose and at 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 12, 14, 16, 24, 36, 48, 72, and 96 h after ACT-451840 dosing. After centrifugation at 1,500 × g for 10 min at 4°C, the plasma samples were transferred to polypropylene tubes and stored between −20°C and −70°C.

Bioanalytical procedures.

The plasma samples were precipitated with three-volume equivalents of the internal standard solution in acetonitrile. After filtration, the plasma concentrations of ACT-451840 were determined by reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) (Agilent 1200; Agilent Technologies, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA), followed by detection with triple-stage quadrupole tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) in positive ion mode (TSY Vantage mass spectrometer; Thermo Fisher, San Jose, CA, USA). ACT-451840 and its internal standard (pentadeuterated ACT-451840) were separated on a YMC Pro C4 column (2.1 by 50 mm, 5 μm) (Agilent Technologies, Inc.) using a gradient containing acetonitrile and formic acid. The lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) of ACT-451840 was 0.100 ng/ml. The interbatch precision was between 3.9% and 6.8%, whereas the interbatch accuracy was in the range of 96.0% to 101.0% of nominal concentration.

Pharmacokinetic evaluations.

No statistical hypothesis was set for this first-in-humans study. The sample size was based on empirical considerations. The actual blood sampling times were used for the PK evaluation when they deviated by >5% from the scheduled ones. The measured individual plasma concentrations of ACT-451840 were used to calculate the PK parameters. The PK parameters of ACT-451840 were calculated by noncompartmental analysis (NCA) using WinNonlin version 6.1 (Pharsight Corporation, Mountain View, CA, USA).

The measured individual plasma concentrations of ACT-451840 were used to directly obtain the Cmax and time to Cmax (Tmax). The area under the plasma concentration-time curve (AUC) was calculated according to the linear trapezoidal rule, using the measured concentration-time values above the LLOQ, without any weighting. The half-life (t1/2) of ACT-451840 was calculated as follows: t1/2 = ln(2)/λz, where λz represents the terminal elimination rate constant.

Dose proportionality was assessed across ACT-451840 doses in the fasted state using the power model described previously (12), which was applied to the log AUC0–∞ and Cmax data. A point estimate and 90% confidence interval (CI) were produced for the population mean slope. Approximate dose proportionality was to be concluded when the 90% CI for the slope was completely within the interval of 0.82 to 1.18 [1 + log(0.5)/log(r), 1 + log(2)/log(r)], where r is either Cmax or AUC of the highest dose/lowest dose (13).

For once-daily multiple-dose simulations, a model was created based on a compartmental analysis of ACT-451840 plasma concentrations following doses of 200 mg and 500 mg in the fed state, using WinNonlin version 6.1.

Pharmacodynamic assessments.

Blood samples were drawn from the subjects predose and at 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 12, 14, 24, 48, 72, and 96 h after 200- and 500-mg doses of ACT-451840 in the fasted and fed states. As previously described (14, 15), the ex vivo bioassay assesses the proliferation of P. falciparum (lab strain NF54) in the serum of a subject by quantification of [3H]hypoxanthine incorporated in postdose samples relative to predose controls.

The drug concentration that inhibits 50% of the parasite isotope incorporation relative to the drug-free controls (IC50) was calculated by logistic regression analysis. The calculated IC50 for ACT-451840 in the drug-free controls (blank plasma samples spiked with ACT-451840) was 0.2 ng/ml. The active drug concentrations in the bioassay are expressed in equivalents of ACT-451840.

Metabolite identification.

Pooled human plasma in the time window between 2 and 12 h was investigated by HPLC (Shimadzu LC-20ADXR; Shimadzu, Reinach, Switzerland) coupled to high-resolution MS in positive electrospray ionization mode (LTQ Orbitrap Velos Pro; Thermo Fisher, San Jose, CA, USA). Data evaluation was accomplished by UV analysis, using the MetWorks 1.3 and Xcalibur 2.1 software packages (Thermo Electron, San Jose, CA, USA). The difference between the calculated and measured exact mass was always <1 ppm. Putative metabolites were determined by liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) in positive ion mode using collisional activation in the ion trap and fragmentation in a collision cell (higher-energy collision dissociation). Separation of the metabolites was done on a C18 column (4.6 by 250 mm, 5 μm, InertSustain; GL Sciences, Tokyo, Japan) using a gradient containing acetonitrile and ammonium acetate.

Hydrogen-deuterium (H/D) exchange experiments were performed by adding postcolumn a flow of 0.6 ml/min D2O containing 0.1% formic acid to the MS flow. The H/D exchange experiments were used to investigate the number of acidic protons for metabolite identification.

Quantification of identified metabolites.

The human plasma samples were initially pooled per time point from all subjects from the fed 500-mg group and from the placebo group as a control. The pool in the time window between 2 and 12 h was made using 200 μl of plasma per time point. In addition, an AUC proportional pool was prepared according to the method of Hamilton, Garnett, and Kline (16) using all time points, resulting in a single final pooled human plasma sample, representing an equivalent of the AUC from 0 to 96 h (AUC0–96). An aliquot of 400 μl of the pool was treated with 800 μl of acetonitrile containing 5% ethanol (vol/vol) and then diluted with 800 μl of water. The samples were mixed and centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatants were transferred into a glass vial, and 100 μl was submitted to LC-MS/MS analysis (under the same conditions as those for metabolite identification). ACT-606559 (Fig. 1) was used as an authentic standard.

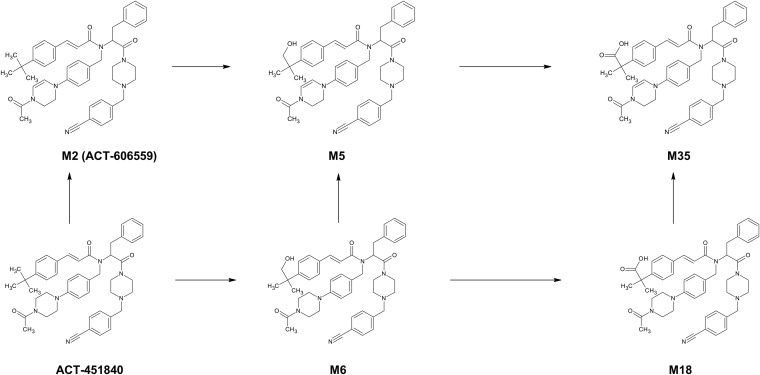

FIG 1.

Proposed metabolic pathways of ACT-451840 in human plasma.

RESULTS

Study population.

A total of 40 subjects, 8 in each of the 5 dose groups, were enrolled in this study. All subjects completed the study as per the protocol.

The majority of the subjects treated in this study were Caucasian (70%), followed by Black (20%). Their mean age was 30.3 years (range, 20 to 43 years), with a mean BMI of 23.4 kg/m2 (range, 20 to 28 kg/m2). The demographic characteristics were similar across the dose groups.

Safety and tolerability.

No serious AEs or AEs leading to discontinuation of the study were reported. Of the 30 subjects treated with ACT-451840, 2 subjects (50-mg dose group) had AEs. One subject had headache, nausea, and vomiting, and the second subject had headache and tonsillitis. The AEs were mild or moderate in intensity. No AEs of severe intensity were reported. One placebo-treated subject in the 500-mg dose group (fed state) had an AE of gastroenteritis.

No clinically relevant mean changes from baseline in hematology, clinical chemistry, coagulation variables, or vital signs were observed. No clinically relevant ECG findings were reported by the investigator or by the external ECG reviewer.

Pharmacokinetics.

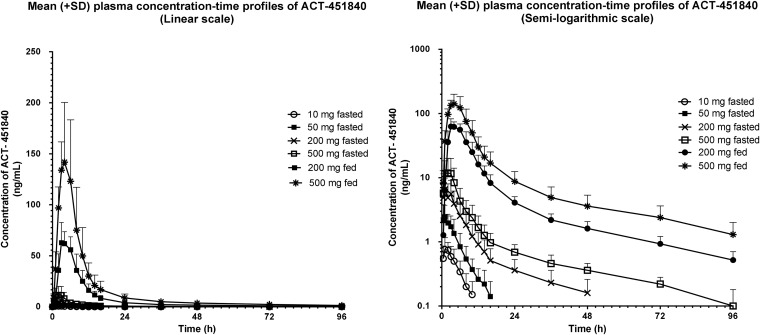

The arithmetic mean (± standard deviation [SD]) plasma concentration-time profiles of ACT-451840 in the different dose groups are shown in Fig. 2. In the fasted state, the plasma concentrations of ACT-451840 were low. In the highest dose group (500 mg) tested in the fasted state, the geometric means (95% CI) for AUC0–∞ and Cmax were 100.6 ng · h/ml (60.8 to 166.5 ng · h/ml) and 11.9 ng/ml (5.7 to 24.9 ng/ml), respectively. Across the dose groups, the Cmax was achieved 0.8 to 2 h after the administration of ACT-451840 in the fasted state. The geometric mean t1/2 values were 3.6 and 4.7 h in the 10- and 50-mg dose groups, respectively. In the higher dose groups (200 and 500 mg fasted), the geometric mean t1/2 values were 28.2 and 33.8 h, respectively.

FIG 2.

Arithmetic mean (±SD) plasma concentration-time profile of ACT 451840 in healthy male subjects after administration of a single dose of 10, 50, 200, or 500 mg of ACT-451840 in the fasted state or 200 and 500 mg of ACT-451840 in the fed state (linear and semilogarithmic scales).

Food effect.

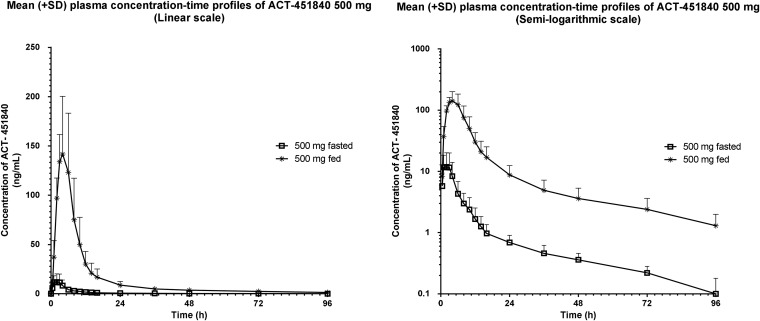

The arithmetic mean (±SD) plasma concentration-time profiles following 500 mg ACT-451840 administered in the fasted and fed states are shown in Fig. 3. The ACT-451840 plasma concentrations in the fed state were significantly higher than those in the fasted state. With a respective geometric mean (95% CI) of 1,408.1 ng · h/ml (928.0 to 2,136.5 ng · h/ml) and 150.5 ng/ml (112.2 to 201.8 ng/ml), the AUC0–∞ and Cmax were approximately 14- and 13-fold greater, respectively, in the fed state than those in the fasted state. The ratio of geometric mean (90% CI) t1/2 values (during fed versus fasted states) was 0.94 (0.74 to 1.20). There was a delay in Tmax, with a median difference (minimum [min] to maximum [max]) between the fed and fasted states of 1.00 h (1.00 to 2.50 h) (Table 1).

FIG 3.

Arithmetic mean (±SD) plasma concentration-time profile of ACT-451840 in the food effect group (500 mg fasted and fed crossover) (linear and semilogarithmic scales).

TABLE 1.

Summary of PK parametersa

| Parameterb | Dose group under indicated conditionc: |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fasted |

Fed |

|||||

| 10 mg | 50 mg | 200 mg | 500 mg | 500 mg | 200 mg | |

| Cmax (ng/ml) | 0.9 (0.6–1.2) | 3.1 (2.1–4.6) | 6.6 (3.1–14.2) | 11.9 (5.7–24.9) | 150.5 (112.2–201.8) | 69.0 (57.0–83.5) |

| Tmax (h) | 1.0 (0.5–2.0) | 0.8 (0.5–3.0) | 2.0 (1.0–3.0) | 2.0 (1.0–3.0) | 3.5 (2.0–6.0) | 3.0 (3.0–6.0) |

| t1/2 (h) | 3.6 (3.0–4.3) | 4.7 (3.6–6.2) | 28.2 (21.7–36.7) | 33.8 (23.4–48.8) | 31.8 (25.3–39.9) | 29.5 (24.7–35.2) |

| AUC0–t (ng · h/ml) | 4.1 (2.6–6.5) | 12.5 (8.1–19.3) | 40.7 (17.1–96.8) | 90.9 (50.6–163.1) | 1,349.7 (895.1–2,035.4) | 643.1 (537.1–770.0) |

| AUC0–∞ (ng · h/ml) | 4.7 (3.1–7.1) | 13.4 (8.9–20.3) | 47.2 (22.3–100.2) | 100.6 (60.8–166.5) | 1,408.1 (928.0–2,136.5) | 665.9 (555.6–798.1) |

The 500-mg fed versus 500-mg fasted ratio of geometric means (90% CI) values are Cmax, 12.66 (7.44 to 21.54); Tmax (median difference [90% CI]), 1.00 (1.00 to 2.50); t1/2, 0.94 (0.74 to 1.20); AUC0–t, 14.85 (9.67 to 22.80); and AUC0–∞, 13.99 (9.52 to 20.57).

Cmax, maximum plasma drug concentration; Tmax, time to reach Cmax; t1/2, terminal half-life; AUC0–t, area under the plasma concentration-time curve from zero to time t of the last measured concentration above the limit of quantification; AUC0–∞, area under the plasma concentration-time curve from zero to infinity.

n = 6 for each dose group. The data are the geometric means (and 95% confidence intervals [CIs]), except for Tmax, which are the median (range).

Similarly, in the subjects dosed with 200 mg in the fed state, the geometric means of AUC0–∞ and Cmax increased by approximately 14- and 11-fold, respectively, compared to those in subjects dosed with 200 mg in the fasted state (Table 1 and Fig. 2). The variability in the AUC0–∞ was moderate, being slightly smaller in the fed state (% coefficient of variation [CV], 41%) than that in the fasted state (%CV, 51%).

Dose proportionality.

After a single-dose administration of ACT-451840 in the fasted state, exposure was slightly less than proportional over the tested dose range (10 to 500 mg). In the power model, the slopes (90% CI) for AUC0–∞ and Cmax were 0.79 (0.67 to 0.91) and 0.66 (0.53 to 0.79), respectively. Both 90% CI were not completely contained within the interval of 0.82 to 1.18. However, a comparison of the geometric means of Cmax and AUC0–∞ for 200 mg and 500 mg in the fed state suggested close-to-dose-proportional increases in Cmax and AUC0–∞ (Table 1).

Simulation of multiple-dose profiles.

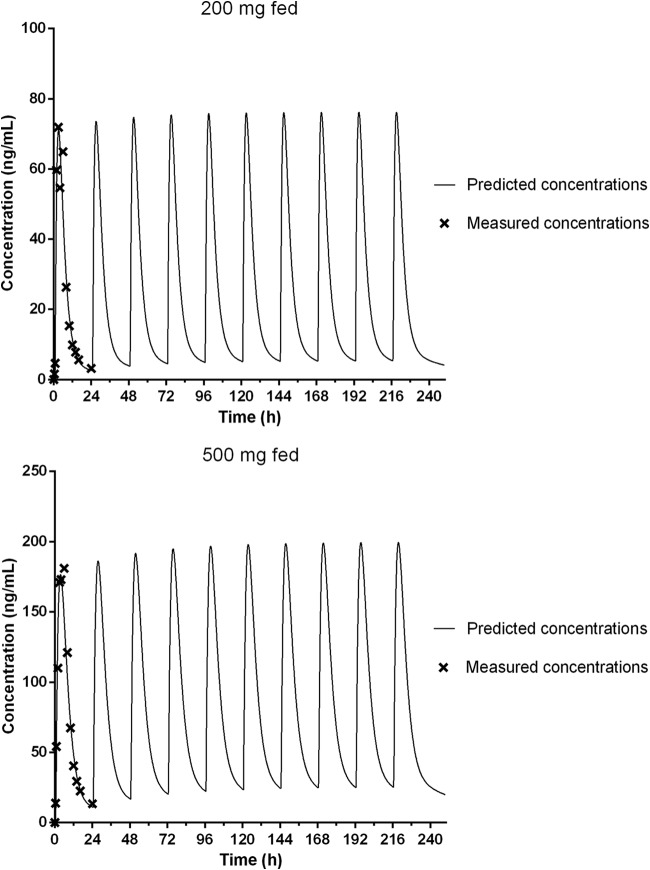

Modeling was performed with the data from the 200- and 500-mg groups in the fed state to predict the dosing regimen for a future multiple-ascending-dose study. The two-compartmental PK model (first-order elimination with lag time) adequately described the PK of ACT-451840. The simulated concentration-time profiles are shown in Fig. 4. Based on these simulations, steady-state conditions would be reached approximately by day 3, and the accumulation of ACT-451840 is estimated to be low (<30%). Also, with 500 mg of ACT-451840 once daily in the fed state, the trough concentration would remain at >15 ng/ml.

FIG 4.

Simulated concentration-time profiles for multiple once-daily doses of 200 and 500 mg of ACT-451840 in the fed state.

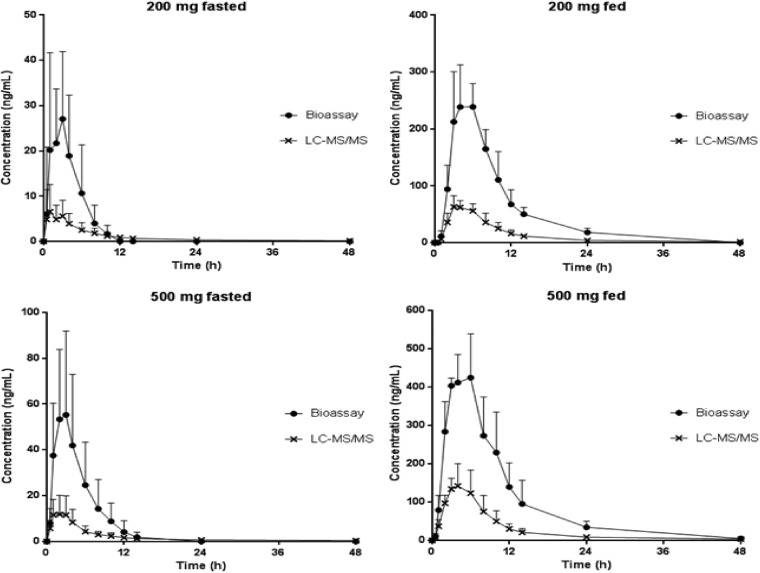

Bioassay.

In the serum samples from subjects treated with 200 and 500 mg of ACT-451840, an increase in antimalarial activity was observed in the samples from 0.5 up to 14 and 48 h postdose in the fasted and fed states, respectively, compared to ACT-451840 spiked into blank serum. To illustrate the ex vivo antimalarial activities of the serum samples compared to the measured concentration of the parent compound, the active drug concentrations expressed in ACT-451840 equivalents via the bioassay are plotted in Fig. 5. Peak antimalarial activity occurred slightly later than the Cmax measured by LC-MS/MS at 2 and 3.5 h postdose in the fasted and fed states, respectively. The geometric mean Cmax estimated by the bioassay was approximately 4× higher than the geometric mean Cmax determined by LC-MS/MS (Fig. 5).

FIG 5.

Arithmetic mean (±SD) concentration-time profiles of ACT-451840 determined by LC-MS/MS and by the bioassay for 200 mg fasted, 500 mg fasted and fed crossover, and 200 mg fed.

Metabolites of ACT-451840 in human plasma.

To identify metabolites, the accurate mass was compared to the theoretical mass (Table 2). H/D exchange with an observed mass shift of 1 Da and MS/MS techniques (data not shown) were also used to propose plausible chemical structures of the metabolites (Fig. 1). For metabolite identification, UV chromatograms of pooled human plasma samples were monitored. The approximate relative proportions of the parent drug and metabolites were deduced from the area of their signals in the UV chromatogram of the AUC0–96 pool, assuming an identical UV response of all metabolites and the parent drug (Table 2). Overall, unchanged parent drug ACT-451840 and five metabolites, M2, M5, M6, M18, and M35, were detected in the human plasma AUC0–96 pool and in the pool over the time window between 2 and 12 h. The retention time and MS/MS spectrum of M2 were consistent with those of the separately injected authentic standard ACT-606559. The metabolite M5 was generated by single hydroxylation and additional dehydrogenation of the parent drug. M6 is formed by single hydroxylation, most likely at the t-butyl moiety. M18 is proposed to be a carboxylated derivative of the parent compound, and M35 corresponds to dehydrogenated M18.

TABLE 2.

Metabolite properties and relative metabolite AUC in plasma from subjects treated with 500 mg ACT-451840 in the fed state

| Drug/metabolite IDa | Retention time (min) | Determined mass [M+H]+ | Theoretical mass [M+H]+ | Change in elemental composition | Relative AUC0–96 as ratio of metabolite and parent drug based on HPLC-UV ACT-451840 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACT-451840 | 63.2 | 751.4329 | 751.4330 | 100 | |

| M2 | 67.5 | 749.4171 | 749.4174 | −2[H] | 76 |

| M5 | 46.9 | 765.4121 | 765.4122 | +[O] −2[H] | 149 |

| M6 | 42.8 | 767.4278 | 767.4279 | +[O] | 123 |

| M18 | 23.5 | 781.4072 | 781.4071 | +2[O] −2[H] | 121 |

| M35 | 25.8 | 779.3913 | 779.3915 | +2[O] −4[H] | 66 |

ID, identification.

DISCUSSION

With regard to safety, ACT-451040 was well tolerated. The most frequently reported AE was headache, which was reported in 2 ACT-451840-treated subjects. Further, the number of AEs did not correlate with exposure.

ACT-451840 is a new chemical entity with potent activities against sensitive and resistant P. falciparum strains. In this first-in-humans study, the geometric mean AUC0–∞ in the highest dose group (500 mg) in the fasted state was approximately 100 ng · h/ml. Based on the results in the humanized mouse model of P. falciparum malaria, this is considerably below the predicted efficacious exposure (estimated AUC, ≈900 ng · h/ml). However, in the presence of high-fat high-calorie food, exposure to ACT-451840 increased 14-fold, leading to a geometric mean AUC0–∞ of 1,408 ng · h/ml, which is higher than the predicted efficacious exposure.

Food can influence drug bioavailability via many mechanisms. To be absorbed (usually in the small intestine), a drug first needs to be solubilized (usually in the stomach). In the fasted state, gastric motility is not uniform, and absorption of poorly soluble drugs may take longer than of highly soluble molecules. Food can influence physical and chemical interactions with a drug substance or a drug formulation. For example, drug suspensions, which contain lipophilic compounds, can have a delayed dissolution in a fasting stomach (e.g., griseofulvin) (17). However, food, and especially fat, increases the solubilization of lipophilic molecules in the gastrointestinal tract. Food alters gastrointestinal pH and gastric motility. Food also increases gastric secretion, bile secretion, fluid volume, and residence time, which leads to a better dissolution, because bile micelles increase the solubility of lipophilic compounds (18). It has also been shown that food increases splanchnic blood flow and, consequently, the absorption rate (17). The exact mechanism of how a high-fat meal increased the exposure of the subjects to ACT-451040 is unknown but is likely to be the result of a combination of several of these mechanisms, since ACT-451840 is a lipophilic compound, administered as a suspension.

Such a food effect has also been observed with other lipophilic antimalarial drugs, such as lumefantrine, which showed a 16-fold increase in bioavailability with food (19). It was also reported that for this compound, only very small amounts of fat (1.6 g) are necessary to achieve adequate exposure. This level of fat is also easily reached in the African diet or in breast milk (20). Another possible solution to mimic the food effect would be to develop a new formulation, such as a lipid-based drug delivery system. This kind of system is currently being developed for β-arteether, for which several self-emulsifying drug delivery systems are currently under investigation (21). It has been shown that a change in formulation, especially in lipid composition, can also impact bile secretion, which in turn enhances the solubility of the drug (22).

Even though food did not affect the t1/2, it varied between the dose groups in the fasted state. This might be related to the very low concentrations of ACT-451840 in the 10- and 50-mg dose groups, which approached the LLOQ very quickly and therefore did not allow accurate determination of the terminal phase, leading to an underestimation of the terminal t1/2 for the lowest doses.

A power model has been used in order to investigate the dose proportionality in PK in the dose range of 10 to 500 mg in the fasted state. No formal dose proportionality was shown in this dose range, but a close to dose proportionality could be suggested for the 200- and 500-mg doses in the fed state by a comparison of the geometric means of Cmax and AUC0–∞. Therefore, further investigation of dose proportionality is needed in the therapeutic exposure range.

In a comparison of the results of the bioassay with those of the LC-MS/MS analysis, the differences observed for peak antimalarial activity suggest the presence of circulating active metabolites of ACT-451840 that contribute to the antimalarial activity of the parent compound. One metabolite, M2, produced an identical MS/MS spectrum and retention time as those of the synthesized standard ACT-606559. The antimalarial activity of this molecule was confirmed in human serum, although its potency is about 25 times lower than of ACT-451840. Further, M2 is present at only 76% of the relative ACT-451840 AUC0–96. Currently, it is not clear whether the contribution of M2 can entirely explain the increased ex vivo antimalarial activity due to the unknown free fraction in plasma of M2 in relation to that of ACT-451840. Therefore, other identified metabolites might also contribute to the antimalarial activity observed in the bioassay.

In vitro studies with [14C]ACT-451840 have shown that this compound is highly bound to human plasma proteins (99.96%). The extent of blood/plasma partitioning of ACT-451840 was 0.58. Twelve percent of the ACT-451840 present in the human blood was bound to uninfected erythrocytes (our unpublished data). This indicates that ACT-451840 has limited penetration into uninfected erythrocytes. For some antimalarial drugs, partitioning into erythrocytes is influenced by infection with parasites (23–25) and, therefore, these properties deserve further investigation. Such data may help to further elucidate the mechanism of action of ACT-451840. The minimal parasiticidal concentration of ACT-451840 for two life cycles of the parasite is estimated at 1.5 ng/ml (unpublished data). According to the simulations, this is 10 times lower than the trough concentration obtained with the regimen of 500 mg of ACT-451840 once daily in the fed state. The presence of food was shown to markedly increase the exposure to ACT-451840. The results of the present study suggest that ACT-451840 is a candidate warranting further clinical investigation in a proof-of-concept study.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Sergio Wittlin, Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute, Basel, Switzerland, for conducting the bioassay, Amélie Le Bihan and Sandrine Gioria (both Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd.) for their contributions in preclinical and clinical project management, respectively, Wenting Zhang-Fu for medical input and assessment, and Christoph Siethoff, Swiss Bioquant, Reinach, Switzerland, for bioanalytical assessments.

This work was supported by Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd.

S.B., N.H., R.d.K., T.M., T.P., and J.D. are full-time employees of Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd. Y.D. is a full-time employee of Eurofins Optimed.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization (WHO). 2008. Global malaria action plan, for a malaria-free world. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland: http://www.rollbackmalaria.org/gmap/gmap.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization (WHO). 2012. WHO, world malaria report 2012. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland: http://www.who.int/malaria/publications/world_malaria_report_2012/wmr2012_no_profiles.pdf?ua=1. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Noor AM, Kinyoki DK, Mundia CW, Kabaria CW, Mutua JW, Alegana VA, Fall IS, Snow RW. 2014. The changing risk of Plasmodium falciparum malaria infection in Africa: 2000–10: a spatial and temporal analysis of transmission intensity. Lancet 383:1739–1747. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62566-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization (WHO). 2012. Global malaria program: update on artemisinin resistance, April 2012. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland: http://www.who.int/malaria/publications/atoz/arupdate042012.pdf?ua=1. [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization (WHO). 2012. Emergency response to artemisinin resistance in the greater Mekong subregion: regional framework for action 2013–2015. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/79940/1/9789241505321_eng.pdf?ua=1. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gamo FJ, Sanz LM, Vidal J, de Cozar C, Alvarez E, Lavandera JL, Vanderwall DE, Green DV, Kumar V, Hasan S, Brown JR, Peishoff CE, Cardon LR, Garcia-Bustos JF. 2010. Thousands of chemical starting points for antimalarial lead identification. Nature 465:305–310. doi: 10.1038/nature09107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brunner R, Aissaoui H, Boss C, Bozdech Z, Brun R, Corminboeuf O, Delahaye S, Fischli C, Heidmann B, Kaiser M, Kamber J, Meyer S, Papastogiannidis P, Siegrist R, Voss T, Welford R, Wittlin S, Binkert C. 2012. Identification of a new chemical class of antimalarials. J Infect Dis 206:735–743. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Janse CJ, Waters AP, Kos J, Lugt CB. 1994. Comparison of in vivo and in vitro antimalarial activity of artemisinin, dihydroartemisinin and sodium artesunate in the Plasmodium berghei-rodent model. Int J Parasitol 24:589–594. doi: 10.1016/0020-7519(94)90150-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.European Medicines Agency 2002. ICH topic E 6 (R1): guideline for good clinical practice. European Medicines Agency, London, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 10.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 2005. Guidance for industry: estimating the maximum safe starting dose in initial clinical trials for therapeutics in adult healthy volunteers. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER), Rockville, MD: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/Guidances/UCM078932.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 11.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 2002. Guidance for industry: food-effect bioavailability and, fed bioequivalence studies. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER), Rockville, MD: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/RegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM126833.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gough K, Hutchison M, Keene O, Byrom B, Ellis S, Lacey L, McKellar J. 1995. Assessment of dose proportionality: report from the statisticians in the pharmaceutical industry/pharmacokinetics UK joint working party. Drug Inform J 29:1039–1048. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith BP, Vandenhende FR, DeSante KA, Farid NA, Welch PA, Callaghan JT, Forque ST. 2000. Confidence interval criteria for assessment of dose proportionality. Pharm Res 17:1278–1283. doi: 10.1023/A:1026451721686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Teja-Isavadharm P, Peggins JO, Brewer TG, White NJ, Webster HK, Kyle DE. 2004. Plasmodium falciparum-based bioassay for measurement of artemisinin derivatives in plasma or serum. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 48:954–960. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.3.954-960.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moehrle JJ, Duparc S, Siethoff C, van Giersbergen PL, Craft JC, Arbe-Barnes S, Charman SA, Gutierrez M, Wittlin S, Vennerstrom JL. 2013. First-in-man safety and pharmacokinetics of synthetic ozonide OZ439 demonstrates an improved exposure profile relative to other peroxide antimalarials. Br J Clin Pharmacol 75:524–537. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04368.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamilton RA, Garnett WR, Kline BJ. 1981. Determination of mean valproic acid serum level by assay of a single pooled sample. Clin Pharmacol Ther 29:408–413. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1981.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Winstanley PA, Orme ML. 1989. The effect of food on drug bioavailability. Br J Clin Pharmacol 28:621–628. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1989.tb03554.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sugano K, Kataoka M, Mathews Cda C, Yamashita S. 2010. Prediction of food effect by bile micelles on oral drug absorption considering free fraction in intestinal fluid. Eur J Pharm Sci 40:118–124. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2010.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ashley EA, Stepniewska K, Lindegårdh N, Annerberg A, Kham A, Brockman A, Singhasivanon P, White NJ, Nosten F. 2007. How much fat is necessary to optimize lumefantrine oral bioavailability? Trop Med Int Health 12:195–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2006.01784.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Djimdé A, Lefèvre G. 2009. Understanding the pharmacokinetics of Coartem. Malar J 8:1–8. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-8-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Memvanga PB, Préat V. 2012. Formulation design and in vivo antimalarial evaluation of lipid-based drug delivery systems for oral delivery of β-arteether. Eur J Pharm Biopharm 82:112–119. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2012.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holm R, Tønsberg H, Jørgensen EB, Abedinpour P, Farsad S, Müllertz A. 2012. Influence of bile on the absorption of halofantrine from lipid-based formulations. Eur J Pharm Biopharm 81:281–287. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2012.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vyas N, Avery BA, Avery MA, Wyandt CM. 2002. Carrier-mediated partitioning of artemisinin into Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 46:105–109. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.1.105-109.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pooley S, Fatih FA, Krishna S, Gerisch M, Haynes RK, Wong HN, Staines HM. 2011. Artemisone uptake in Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:550–556. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01216-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.San George RC, Nagel RL, Fabry ME. 1984. On the mechanism for the red cell accumulation of mefloquine, an antimalarial drug. Biochim Biophys Acta 803:174–181. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(84)90007-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]