Abstract

Short-term exposure to fine particle mass (PM) has been associated with adverse health effects, but little is known about the relative toxicity of particle components. We conducted a systematic review to quantify the associations between particle components and daily mortality and hospital admissions. Medline, Embase and Web of Knowledge were searched for time series studies of sulphate (SO42−), nitrate (NO3−), elemental and organic carbon (EC and OC), particle number concentrations (PNC) and metals indexed to October 2013. A multi-stage sifting process identified eligible studies and effect estimates for meta-analysis. SO42−, NO3−, EC and OC were positively associated with increased all-cause, cardiovascular and respiratory mortality, with the strongest associations observed for carbon: 1.30% (95% CI: 0.17%, 2.43%) increase in all-cause mortality per 1 μg/m3. For PNC, the majority of associations were positive with confidence intervals that overlapped 0%. For metals, there were insufficient estimates for meta-analysis. There are important gaps in our knowledge of the health effects associated with short-term exposure to particle components, and the literature also lacks sufficient geographical coverage and analyses of cause-specific outcomes. The available evidence suggests, however, that both EC and secondary inorganic aerosols are associated with adverse health effects.

Keywords: particle components, mortality, hospital admissions, time series, systematic review

INTRODUCTION

Exposure to outdoor particulate matter with a median aerodynamic diameter <2.5 microns (PM2.5) has been associated with a range of adverse health outcomes.1, 2, 3 Epidemiological evidence comes from cohort studies linking long-term exposure to PM2.5 to adverse health effects and from time series studies that have reported associations between daily concentrations of PM2.5 and increases, within a period of days, in daily numbers of deaths and emergency hospital admissions.

PM2.5 mass is regulated in the United States, Europe and elsewhere but no consideration is given to particle size, source or chemical composition. Policy makers and regulatory authorities have sought to establish which, if any, component of the particle mixture is most dangerous to human health.2 To date, literature reviews have focused on specific components, such as black carbon;4,5 or specific sources such as traffic;6 have been limited by the relatively sparse literature available for review;7, 8, 9 or have been restricted to specific geographical regions.10,11 Other reviews have not provided a systematic, quantitative assessment of the evidence but relied instead upon a qualitative review of a range of study designs and health outcomes.2,12, 13, 14 We conducted a systematic review of the epidemiological time series literature for adverse effects of particle components on mortality and hospital admissions using original research indexed in online databases to October 2013 and without limitation by geographical region, particle component or source or language. We included studies of secondary inorganic aerosols, elemental and organic carbon and size-fractionated particle number concentrations. Our focus was the selection of effects estimates for meta-analysis to provide concentration-response functions for comparative purposes and for health impact assessment. We also provide a qualitative overview of the growing time series literature reporting results for the elemental content of particles.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The Air Pollution Epidemiology Database (APED)15 was used to identify ecological time series studies of the health effects associated with short-term exposure to a range of particle metrics: nitrate (NO3−); sulphate (SO42−); elemental (EC) and organic (OC) carbon; and size-fractionated particle number concentrations (PNC), including nucleation mode (particles with a diameter generally <0.05 μm), Aitken mode (generally 0.05–0.1 μm) and accumulation mode (generally 0.1–0.5 μm)6,16,17 and metals. APED and our systematic review protocol have been described previously.3,15,18 In brief, APED contains details of time series studies (including case crossover designs) published in peer reviewed journals and indexed in PubMed, EMBASE or Web of Science (which includes the Science Citation Index). Studies are identified through periodic searches using the following search criteria: “(particle* or particulate* or aerosol or sulphate or nitrate or carbon or metal) and (timeseries or time-series or time series) and (mortality or death* or dying or hospital admission* or admission* or emergency)”. For this review, studies of particle components indexed up to October 2013 were included. We also cross-checked studies identified in APED against publications selected for other reviews2,9 and publications from the Health Effects Institute.6,13,19 APED includes only studies that meet specific criteria, including: (1) at least 1 year of daily data relating to a general population; (2) a reasonable attempt to control for important confounding factors, such as long-term temporal trends, season and meteorological conditions; and (3) sufficient information for the calculation of a regression estimate and standard error (SE) for inclusion in the quantitative analysis.

Study details were entered into a Microsoft Access database and included publication details, and all data required to characterize the health outcomes, pollutants and effect estimates. From these data, we calculated standardized effect estimates expressed as the percentage change (and 95% confidence interval) in the mean number of daily events associated with a 1-μg/m3 increase in particle concentrations.

A multi-stage process to select estimates for meta-analysis avoided duplication by selecting the most recently published evidence. Meta-analysis was performed only when ≥4 estimates for an outcome/disease/age group were available. Summary estimates were derived using a random-effects model, which calculates a weighted summary estimate using weights determined from the precision of individual study effect estimates.20 The random-effects model assumes that the associations observed in individual studies can vary because of real differences between the associations in each study as well as simple sampling variability (chance) between studies and adjusts the pooled estimates and their 95% confidence intervals accordingly. Where sufficient estimates were available, we carried out stratified analyses by WHO region (details of countries included in each region are available at http://www.who.int/choice/demography/regions/en/) to assess geographical variation. Heterogeneity between study estimates was assessed using the I2 statistic,21 which describes the proportion of the variation in effect estimates attributable to heterogeneity rather than chance.

All analyses were conducted in STATA (STATA/SE 10. StataCorp, Texas, USA).

RESULTS

Literature Search

Our review identified 63 studies indexed in medical databases to October 2013. Two studies were excluded from our review: a reanalysis of the existing data sets22 and one that was unavailable online23. Of the 61 studies, 40 investigated daily mortality and 27 hospital admissions. Secondary inorganic aerosols were investigated in 35 studies (SO42−), 11 of which also considered NO3−; elemental and organic carbon was investigated in 19 studies; particle number concentrations in 12 studies; and particle elemental composition in 19 studies. Table 1 gives the numbers of studies by outcome, disease category and particle metric investigated stratified by WHO Region. The majority of studies were from North America and Europe although we note the very recent growth in studies from China (published in 2011–12). A number of cities were the subject of investigation on multiple occasions, both in single- and multi-city studies. A bibliography for the 63 studies included in our review is given in the Supplementary Data.

Table 1. Numbers of time series studies stratified by outcome, disease, particle metric and continent.

| Continent (WHO region codes) |

Outcome |

Disease |

Particle metric |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mortality | Admissions | All cause | Cardiovascular | Respiratory | SO42- | NO3- | EC/OC | PNC | Metals | |

| North America (AMR A & B) | 21 | 20 | 16 | 21 | 20 | 29 | 6 | 13 | — | 12 |

| South America (AMR C) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | — | — | 2 | — | 2 |

| Europe (EUR A, B & C) | 10 | 7 | 7 | 11 | 8 | 3 | 2 | — | 10 | 1 |

| Western Pacific (WPR B) | 7 | — | 5 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| Total | 40 | 28 | 29 | 40 | 36 | 35 | 11 | 19 | 12 | 19 |

Secondary Inorganic Aerosols and Elemental and Organic Carbon

Mortality

Summary estimates (95% confidence intervals) per 1 μg/m3 increment in SO42−, NO3−, EC and OC for all-age, all-cause and cause-specific mortality are presented in Table 2. Individual study results are presented in a series of forest plots in the (Supplementary Figures S1–S12). The number of all-cause mortality estimates selected for meta-analysis was largest for SO42− (12) compared with 6, 6 and 4 for NO3−, EC and OC, respectively. All four metrics were positively associated with increased all-cause mortality; the largest association per unit mass for elemental carbon, 1.30% (95% CI: 0.17%, 2.43%) and the lowest for SO42−, 0.15% (0.06%, 0.25%). All pollutants were positively associated with cardiovascular mortality, between 1.66% (0.52%, 2.81%) for EC and 0.11% (−0.12%, 0.35%) for NO3−. Associations with respiratory mortality were broadly comparable to those for cardiovascular disease although in all cases confidence intervals straddled 0%. For all but one outcome, there was a strong evidence of between-study heterogeneity.

Table 2. Random effects summary estimates for particle metrics and all-cause and cause-specific mortality.

| Pollutant | Disease | All SC/MCa | Selected SC/MCb | RE (95% CI)c | I2 (%)d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SO42- | All-cause | 14/4 | 9/3 | 0.15 (0.06, 0.25) | 71 |

| Cardiovascular | 9/1 | 8/1 | 0.21 (−0.01, 0.44) | 42 | |

| Respiratory | 8/1 | 7/1 | 0.23 (−0.07, 0.52) | 38 | |

| NO3- | All-cause | 6/1 | 5/1 | 0.17 (0.12, 0.23) | 0 |

| Cardiovascular | 6/1 | 5/1 | 0.11 (−0.12, 0.35) | 70 | |

| Respiratory | 4/1 | 3/1 | 0.15 (−0.29, 0.59) | 68 | |

| EC | All-cause | 6/1 | 5/1 | 1.30 (0.17, 2.43) | 92 |

| Cardiovascular | 5/1 | 4/1 | 1.66 (0.52, 2.81) | 97 | |

| Respiratory | 4/1 | 3/1 | 1.09 (−1.59, 3.85) | 99 | |

| OC | All-cause | 4/1 | 3/1 | 0.37 (−0.19, 0.94) | 99 |

| Cardiovascular | 5/1 | 4/1 | 0.56 (0.01, 1.10) | 97 | |

| Respiratory | 4/1 | 3/1 | 0.57 (−1.11, 2.28) | 98 |

Number of estimates available from all single/multi-city studies.

Number of estimates from single/multi-city studies selected for meta-analysis (see Methods for details of estimate selection protocol).

Random effects summary estimate expressed as percentage of change in the number of deaths per 1 μg/m3 (95% confidence interval).

I2 percentage of between-city variability attributed to heterogeneity.

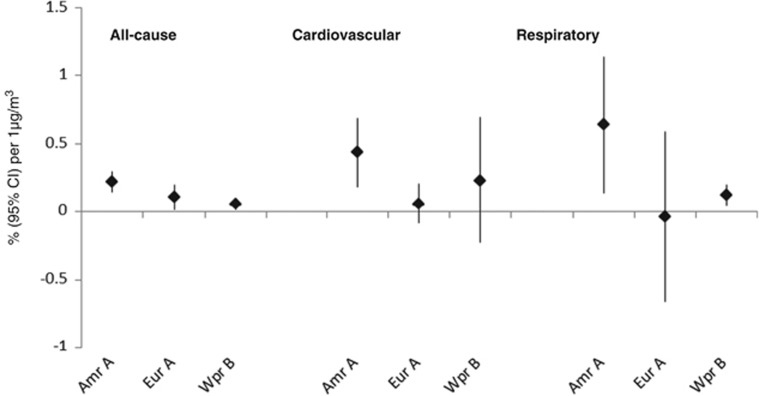

For SO42−, sufficient estimates were available for a subgroup analysis by WHO region (Figure 1). There was evidence of heterogeneity between WHO regions for all-cause mortality (χ2=15.0; P=0.001), cardiovascular (χ2=5.2; P=0.08) and respiratory mortality (χ2=4.7; P=0.10). For each disease group, associations in North America were larger than in European and Western Pacific regions. Mortality associations for secondary inorganic aerosols and carbon were reported for a range of other disease/age group combinations but with too few estimates for meta-analysis.

Figure 1.

Region-specific summary estimates for the associations between sulphate and all-cause and cause-specific mortality.

Hospital admissions

Both cardiovascular (including cardiac) and respiratory hospital admissions in all-ages/65+ years were associated with increases in SO42−: 0.12% (−0.04%, 0.29%) (5 estimates, I2=61%) and 0.14% (−0.07%, 0.35%) (6 estimates, I2=57%) per 1 μg/m3, respectively. Individual study results are presented in Supplementary Figures S13 and S14. For NO3−, EC and OC, there were insufficient numbers of estimates to carry out a meaningful meta-analysis. We note, however, the findings from a large, multi-city study of 119 US counties reporting positive associations for EC and mixed evidence for NO3− and OC and both cardiovascular and respiratory admissions.9

Particle Number Concentrations

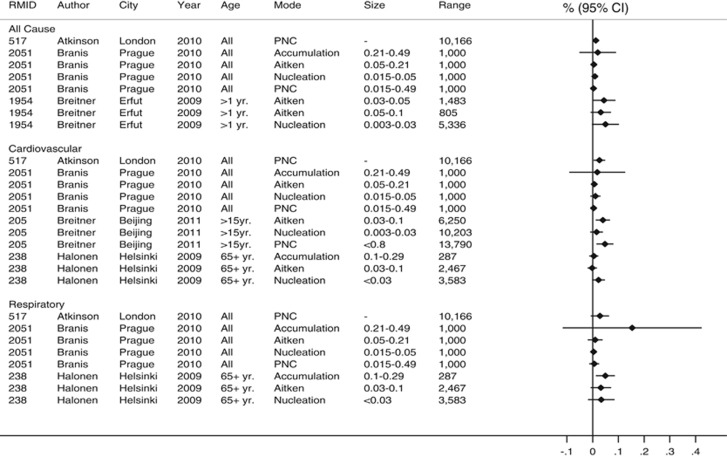

Studies of PNC concentrations assessed a range of size-fractionated number concentrations in relation to daily mortality. After application of our estimate selection protocol, there were too few estimates within each disease/mode grouping to carry out separate meta-analyses. Figure 2 summarizes the results for mortality for nucleation, Aitkin/accumulation mode particles and for total number concentrations where reported in the selected studies. The figure shows results scaled by interquartile range for individual metrics to facilitate within-, rather than between-, study comparison. Although the majority of associations were positive, most had confidence intervals that overlapped 0 (%), and little pattern in the associations could be discerned between the different modes. For PNC and hospital admissions, there were insufficient numbers of estimates to carry out a meaningful meta-analysis (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Individual study results for particle number concentrations and mortality.

Metals

Table 3 summarizes the scope and main findings of the 19 studies reporting results for the elemental content of particles. Studies from North America dominate the available literature (11 from the USA and 2 from Canada). Daily mortality and hospital admissions were investigated in 14 and 5 studies, respectively, and a range of the metals studied (between 3 and 57 elements). Fourteen studies reported regression coefficients for individual elemental concentrations, and five studies reported coefficients for PM2.5 mass in proportion to elemental composition. For mortality, zinc was positively associated with daily mortality in 8/11 studies, nickel in 5/9 studies and vanadium in 3/5 studies.

Table 3. Summary of main findings from studies of elemental content of particles.

| First Author | Year | City/country | Diseases | Study period | Pollutants | Statistical approach | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hoek | 1997 | Rotterdam, Netherlands | All-cause mortality | 1983–1991 | Fe | Poisson regression, single pollutant | No statistically significant associations with mortality |

| Burnett | 2000 | 8 cities in Canada | All-cause mortality | 1986–1996 | 47 elements | Poisson regression, single pollutant | Fe, Ni, and Zn were most strongly associated with increased mortality. Fine-fraction of Ca, Cu, Sc, Co, Zr, P, La and Mg were also found to have some association with mortality |

| Mar | 2000 | Phoenix, USA | All-cause and cardiovascular mortality | 1995–1997 | S, Zn, Pb | Poisson regression, single pollutant | S and Pb negatively associated with total mortality. No other statistically significant associations. Metals represent between 0.3 and 0.5% of total PM2.5 mass |

| Cancado | 2006 | Piracicaba, Brazil | Respiratory hospital admissions | 1997–1998 | Al, Si, S, K and Mn | Poisson regression, single pollutant | Al, Si, S, K and Mn significantly associated with child respiratory admissions. K associated with elderly respiratory hospital admissions. Biomass burning predominant source of particles |

| Lippmann | 2006 | 60 MSAs in USA | Mortality | 2000–2003 | Al, As, Cr, Cu, Fe, Mn, Ni, Pb, Se, Si, V, Zn | Meta-regression of PM10 risk on components | PM10 risk coefficients were high in MSAs where Ni and V were significantly high (95th percentile) compared with the MSAs where Ni was low (5th percentile) |

| Brook | 2007 | 10 cities in Canada | All-cause mortality | 1980–2000 | Fe, Zn, Ni, Mn, As, Al, Cu, Pb, Si, Se | Poisson regression, single pollutant | Zn and Pb significantly associated with increased mortality; Ni borderline significance. All others (except Al) positive but not statistically significant |

| Ostro | 2007 | 6 California counties, USA | All-cause, cardiovascular and respiratory mortality | 2000–2003 | Al, Br, Ca, Cl, Cu, Fe, K, Mn, Ni, Pb, S, Si, Ti, V, Zn | Poisson regression, single pollutant | Strongest associations were observed for Cu, K, Ti and Zn. All except Al, Br, Cu and Ni positively and significantly associated with all-cause mortality in cooler months |

| Franklin | 2008 | 25 US communities | All-cause, cardiovascular and respiratory mortality | 2000–2005 | Al, As, Br, Cr, Fe, K, Mn, Ni, Pb, Si, V, Zn | Meta-regression of PM2.5 risk on components | PM2.5 association higher when PM2.5 mass contained a higher proportion of Al, Arsenic, Si and Ni |

| Ostro | 2009 | 6 California counties, USA | Respiratory hospital admissions | 2000–2003 | Cu, Fe, K, Si, Zn | Poisson regression, single pollutant | Cu, Fe and Si significantly associated with increased respiratory admissions and Cu, Fe and Si with asthma admissions in subjects aged <19 years |

| Ito | 2010 | New York, USA | Cardiovascular mortality and hospital admissions | 2000–2006 | Ni, V, Zn, Si, Se, Br | Poisson regression, single pollutant | Se showed a strong association with CVD mortality as did Br (warm season only). Ni, V and Zn associated with CVD mortality (stronger in cold season). Ni, Zn, Si, Se and Br associated with CVD hospitalizations (strongest in the cold season |

| Suh | 2011 | Atlanta, USA | Cardiovascular and respiratory hospital admissions | 1998–2006 | Transition metal oxides of Cu, Mn, Zn, Ti, Fe | Two stage: Logistic regression and meta-regression to categories | Consistent and significant associations between transition metals and increased hospital admissions for CVD, CHF and IHD in both first-stage and second-stage analyses |

| Zhou | 2011 | Detroit and Seattle, USA | All-cause, cardiovascular and respiratory mortality | 2002–2004 | Al, Fe, K, Na, Ni, S, Si, V, Zn | Poisson regression, single pollutant | Detroit: Warm season, S positively associated with AC and CV mortality. Seattle: cold season, Al, K, Si and Zn positively associated with AC and CV mortality |

| Valdes | 2012 | Santiago, Chile | All-cause, cardiovascular and respiratory mortality | 1998–2007 | Al, Na, Si, S, Cl, Ca, Cr, Mn, Ni, K, Fe, Cu, Zn, Se, Br, Pb | Poisson regression using mean monthly ratio of each individual element to PM2.5 mass | Zn associated with higher cardiovascular mortality. Particles with high content of Cr, Cu and S showed stronger associations with respiratory and COPD mortality. Zn and Na content of PM2.5 amplified the association with cerebrovascular disease |

| Cao | 2012 | Xi'an, China | Cardiovascular and respiratory mortality | 2004–2008 | S, Cl, K, Ca, Ti, Cr, Mn, Fe, Ni, Zn, As, Br, Mo, Cd, Pb | Poisson regression, singly and adjusted for PM2.5 | Cl and Ni showed the strongest associations followed by S, K and As. No positive associations observed for Ca, Ti, Cr, Mn, Fe, Zn, Br, Mo, Cd and Pb |

| Huang | 2012 | Xi'an, China | All-cause, cardiovascular and respiratory mortality | 2004–2008 | S, K, Ca, Fe, Zn, Cl, Pb, Mn, Br, Cd, Ni, Cr | Poisson regression, single pollutant | S, Cl, Cr, Pb, Ni andZn appeared most responsible for increased risk of death, particularly in the cold months |

| Son | 2012 | Seoul, South Korea | All-cause, cardiovascular and respiratory mortality | 2008–2009 | Cl, Ca, Mg, K and Na | Poisson regression, single pollutant | Mg associated with increased total mortality. Mg and Cl exhibited moderate associations with respiratory mortality |

| Sacks | 2012 | Philadelphia, USA | Cardiovascular mortality | 1992–1995 | Cu, Zn, Br, Pb, Fe, Si, Ca, Mn, Ni, V, Se, S and K | Poisson regression, single pollutant | Consistent positive associations were observed for all pollutants, except Ni |

| Bell | 2012 | 187 US counties, USA | Cardiovascular and respiratory hospital admissions | 2000–2005 | 52 chemical components of PM2.5 | Component fraction of PM2.5 total mass | Higher PM2.5 effect estimates for cardiovascular or respiratory hospitalizations were observed in seasons and counties with a higher PM2.5 content of Ni and V |

| Wong | 2012 | Hong Kong, China | All-cause, cardiovascular and respiratory mortality | 1990–1995 | Al, Fe, Mn, Ni, V, Pb, Zn | Poisson regression, single pollutant | Ni and V significantly associated with all-cause and respiratory mortality |

DISCUSSION

Our review identified a growing literature regarding the health effects associated with short-term exposure to particle components, including secondary aerosols, carbon, particle number concentrations and metals. In the 3 years since the last review of the literature on secondary aerosols and carbon and mortality and hospital admissions,9 the number of published studies has increased by 50% (14–21). Furthermore, the broad search strategy used for our review identified an additional 26 population-based time series studies of mortality and hospital admissions, with additional studies including PNC and metals. Although the majority of the studies in our review were still from North America, we note the very recent growth in the number of studies conducted in Asia (six studies in 2012) covering a range of health outcomes and particle metrics. The larger number and scope of studies included in our review has therefore enabled: (1) the quantification of associations between secondary aerosols and carbon and cause-specific mortality; (2) quantification for sulphate and respiratory and cardiovascular admissions; and (3) a comprehensive, descriptive assessment of the evidence for PNC and metals.

In our review, meta-analytical summary estimates were positive but lacked precision for most cause-specific mortality groups. The largest association observed was for elemental carbon, 1.3% increase in all-cause mortality per 1 μg/m3 increase in EC based upon only six studies from the United States, Chile, China and South Korea. Previous reviews of EC have incorporated results for Black Smoke (a light reflectance measurement method calibrated to mass concentration) in their analyses due to the sparseness of direct estimates for EC and have tended to report smaller effect estimates.5,9 We also note the strong heterogeneity between these six estimates and the lack of adjustment for co-pollutants, both of which require careful investigation before assigning prominence to these findings.

Our findings for SO42− and NO3− and mortality were consistent with the findings of Levy et al.9 but are based upon a broader geographical literature incorporating evidence from Asia and without duplication of study locations. To our knowledge, our summary estimates for SO42− and NO3− and hospital admissions for cardiovascular and respiratory disease are new. However, they are dominated by the 119 US counties study,9 with little evidence available from other parts of the world. The literature is also sparse for studies of specific disease sub-groups and tends to be limited to North America, Europe and Western Pacific region.

Ultrafine particles (UFP) are characterized by size (<100 nm), high numbers and relatively large surface area. Our review found little consistent evidence of an association between UFP and daily mortality—a conclusion also reached in recent reviews.1,2,19 UFPs are also characterized in terms of the particle size; nucleation mode particles (<50 nm in diameter) result from gas-to-particle conversion of different chemical compounds and Aitken mode particles (50–100 nm) by direct emission from combustion processes, for example, soot particles from cars.6 In our review, neither modes were differentiated in terms of their effects on mortality although the evidence base was too limited to draw firm conclusions. Of the 15 studies of UFP identified for review, 10 were conducted in just four locations: Erfurt (4), Helsinki (2), Copenhagen (2) and Beijing (2). A broader geographical study base would therefore be advantageous in building a more complete picture of the evidence for the adverse health effects of UFP.

Our qualitative review of the literature reporting results for the elemental content of particles suggests that in the majority of studies Zn, Ni and vanadium were associated with increased mortality. Zn may be indicative of a road dust and possibly a tyre wear source, Fe and Zn are linked to steel production and Ni linked to oil combustion24 or, in a specific case, to a Nickel smelter.25 Our qualitative review highlighted some of the difficulties in assessing the relative effects of particle elemental composition: (1) studies varied in the range of metals investigated making synthesis difficult; (2) in a number of studies measurements were frequently below detection limits13 or not measured daily,26 reducing statistical power; (3) measurements were poorly correlated across monitor locations or measured at one location only with the potential for exposure measurement error;27, 28, 29 and (4) statistical methods varied with some studies considering mass concentrations of individual elements and others reporting coefficients for PM2.5 apportioned by elemental composition. The need to properly account for potential confounding by PM2.5 in the analyses of particle constituents has been suggested by Mostofsky et al30 adding to the difficulty in synthesizing the evidence. A significant strength of these studies, however, is their ability to characterize fully the particle mixture. Some studies that have characterized particles fully have utilized source apportionment techniques.31, 32 However, they have not been included in our review as they do not report numerical coefficients suitable for inclusion in a quantitative review and meta-analysis for health impact assessment, but we recognize the policy relevance of identifying PM source components most associated with adverse health outcomes. Finally, as for particle numbers, a broader geographical study base would be helpful in identifying the toxic components of particles and deriving concentration-response functions.

Our study had a number of strengths, including a very recent literature search (to October 2013); an a priori protocol for the identification of relevant studies and selection of effect estimates for meta-analysis to minimize selection bias; and no limitations on language (although all of the studies were written in English). Our study protocol ensured that multiple results from a single location did not have a disproportionate influence upon summary estimates. However, this approach reduced the number of meta-analyses possible when the evidence was limited to a small number of locations that were repeatedly studied. Other limitations of our review included potential bias arising from reliance upon authors' selection of results to submit for publication and limited ability to investigate reasons for the heterogeneity observed between studies. New studies are required to assess fully the impact of these factors upon the size and precision of the concentration-response functions derived in our meta-analysis. Our review focused upon the evidence from single pollutant models as our primary aim was quantification of effect estimates using meta-analysis. However, a single pollutant approach provides only limited insight into the differential toxicity of particle constituents, a point noted by Levy et al.9 The literature for multi-constituent models remains limited with heterogeneity in the analytical methods used and the reporting of results.

The current literature is dominated by studies of mortality from broad disease categories. Few studies have reported effect estimates for specific causes of death, for example, from ischaemic heart disease, stroke or COPD or for age- and disease-specific hospital admissions. Furthermore, only a handful of studies have considered a range of health end points, diseases and particle components in the same population and hence facilitating meaningful within-study comparison. The literature is also dominated by studies from North America although we note the recent increase in studies from Asia. Further studies from other developed, and developing, countries, are needed to confirm the observed associations. Also, additional studies including specific, rather than broad, categories of diseases would provide additional understanding of the populations at risk and may also add to our understanding of mechanism of effect.

Fine particle mass (PM2.5) has been studied and reviewed extensively, and little doubt remains regarding the adverse health effects of both long- and short-term exposure.2,8,11,24,33,34 However, the uncertainty regarding the components of PM responsible for the adverse health effects remains despite efforts to evaluate the relative toxicity of the various chemical and physical properties of PM.2,9,13,14 Our review of the time series literature provides support for these conclusions although we note, albeit with some caution as our analyses were based upon single-pollutant models only, the larger relative risks for mortality per unit mass of EC compared with other metrics. It should be noted that the interquartile range for EC is much smaller than for sulphate and nitrate aerosol and that both potency and total impact are relevant for policy decisions. A recent review of the toxicological literature35 concluded that the limited new evidence did not change the view from an earlier review36 that secondary inorganic aerosols “have little biological potency in normal human beings”. They do, however, offer a word of caution noting that “it cannot be excluded that these secondary inorganic components produce an interactive biological effect with constituents of the overall pollutant mix by, for example, influencing the bioavailability of other components, such as metals”. The authors of the 2013 review also note a word of caution regarding elemental carbon suggesting “(EC) may not be a major directly toxic component of fine PM” and suggesting, as for secondary inorganic aerosols, that it may act as a “a universal carrier of a wide variety of combustion derived chemical constituents of varying toxicity to sensitive targets in the human body”.

The NPACT investigators recommended that further studies should improve individual and population exposure estimates before “it can be concluded that regulations targeting specific sources or components of PM2.5 will protect public health more effectively than continuing to follow the current practice of targeting PM2.5 mass as a whole”.13,14 Systematic review and quantitative meta-analysis will continue to have an important role in collating and combining the growing body of evidence. Further characterization of air pollution environments and sources will also enable the between-study heterogeneity and any potential confounding to be investigated further improving our understanding of the role of specific particle components. In the mean time, we recommend that the potential health benefits of air pollution mitigation policies are evaluated for a range of particle metrics, particularly elemental carbon, in addition to a single mass metric.

Acknowledgments

This is an independent research commissioned by the Policy Research Programme in the Department of Health. The views expressed are not necessarily those of the Department.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Journal of Exposure Science and Environmental Epidemiology website (http://www.nature.com/jes)

Supplementary Material

References

- EPA. Integrated science assessment for particulate matter (Final report). U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, EPA/600/R-08/139F, 2009. Available from http://cfpub.epa.gov/ncea/cfm/recordisplay.cfm?deid=216546#Download [accessed 15 June 2013]. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Review of evidence on health aspects of air pollution—REVIHAAP project: Final technical report. The WHO European Centre for Environment and Health: Bonn, Switzerland, 2013. Available from http://www.euro.who.int/en/what-we-do/health-topics/environment-and-health/air-quality/publications/2013/review-of-evidence-on-health-aspects-of-air-pollution-revihaap-project-final-technical-report [accessed August 2013]. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson RW, Kang S, Anderson HR, Mills IC, Walton HAEpidemiological time series studies of PM2.5 and daily mortality and hospital admissions - a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax 2014; 69: 660–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KR, Jerrett M, Anderson HR, Burnett RT, Stone V, Derwent R et al. Public health benefits of strategies to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions: health implications of short-lived greenhouse pollutants. Lancet 2009; 374: 2091–2103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen NA, Hoek G, Simic-Lawson M, Fischer P, van Bree L, ten Brink H et al. Black carbon as an additional indicator of the adverse health effects of airborne particles compared with PM10 and PM2.5. Environ Health Perspect 2011; 119: 1691–1699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HEI Panel on the Health Effects of Traffic-Related Air Pollution. 2010. Traffic-related air pollution: a critical review of the literature on emissions, exposure, and health effects. Special Report 17. Health Effects Institute: Boston, MA, USA, Available from http://pubs.healtheffects.org/getfile.php?u=553 [accessed 14 March 2013]. [Google Scholar]

- Reiss R, Anderson EL, Cross CE, Hidy G, Hoel D, McClellan R et al. Evidence of health impacts of sulfate- and nitrate-containing particles in ambient air. Inhal Toxicol 2007; 19: 419–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rückerl R, Schneider A, Breitner S, Cyrys J, Peters AHealth effects of particulate air pollution: a review of epidemiological evidence. Inhal Toxicol 2011; 23: 555–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy JI, Diez D, Dou Y, Barr CD, Dominici FA meta-analysis and multisite time series analysis of the differential toxicity of major fine particulate matter constituents. Am J Epidemiol 2012; 175: 1091–1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira BFA, Ignotti E, Hacon SSA Systematic Review of the Physical and Chemical Characteristics of Pollutants from Biomass Burning and Combustion of Fossil Fuels and Health Effects in Brazil. Cad. Saúde Pública: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil 2011; 27(9): 1678–1698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health Effects Institute. Health effects of outdoor air pollution in developing countries of asia: a literature review. Health Effects Institute: Boston, MA, USA, 2004. Special Report 15. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation. Health relevance of particulate matter from various sources: report on a WHO workshop, Bonn, Germany, March 2007. World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark,2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ito K, Ross Z, Zhou J, Nádas A, Lippmann M, Thurston GDNPACT Study 3. time-series analysis of mortality, hospitalizations, and ambient PM2.5 and its components. In: National Particle Component Toxicity (NPACT) Initiative: Integrated Epidemiologic and Toxicologic Studies of the Health Effects of Particulate Matter Components. Health Effects Institute: Boston, MA, USA, 2013. Research Report 177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippmann M, Ito K, Hwang JS, Maciejczyk P, Chen LCCardiovascular effects of nickel in ambient air. Environ Health Perspect 2006; 114: 1662–1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson HR, Atkinson RW, Bremner SA, Carrington J, Peacock JQuantitative systematic review of short term associations between ambient air pollution (particulate matter, ozone, nitrogen dioxide, sulphur dioxide and carbon monoxide), and mortality and morbidity. Report to Department of Health: London, UK, 2007, Available from https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/quantitative-systematic-review-of-short-term-associations-between-ambient-air-pollution-particulate-matter-ozone-nitrogen-dioxide-sulphur-dioxide-and-carbon-monoxide-and-mortality-and-morbidity (accessed 6 October 2013). [Google Scholar]

- Young LH, Keeler GJSummertime ultrafine particles in urban and industrial air: aitken and nucleation mode particle events. Aerosol Air Qual Res 2007; 7: 379–402. [Google Scholar]

- Branis M, Vyskovska J, Maly M, Hovorka JAssociation of size-resolved number concentrations of particulate matter with cardiovascular and respiratory hospital admissions and mortality in Prague, Czech Republic. Inhal Toxicol 2010; 22: 21–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson HR, Atkinson RW, Peacock JL, Sweeting MJ, Marston LAmbient particulate matter and health effects - publication bias in studies of short-term associations. Epidemiol 2005; 16: 155–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HEI Review Panel on Ultrafine Particles. Understanding the Health Effects of Ambient Ultrafine Particles, HEI Perspectives 3. Health Effects Institute: Boston, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Der Simonian R, Laird NMMeta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 1986; 7: 177–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huedo-Medina TB, Sanchez-Meca J, Marın-Martınez F, Botella JAssessing heterogeneity in meta-analysis: Q statistic or I2 index? Psychol Methods 2006; 11: 193–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health Effects Institute. Revised analyses of time series studies of air pollution and health. Special Report. Health Effects Institute: Boston, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Leitte AM, Petrescu C, Franck U, Richter M, Suciu O, Ionovici R et al. Respiratory health, effects of ambient air pollution and its modification by air humidity in Drobeta-Turnu Severin, Romania. Sci Total Environ 2009; 407: 4004–4011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnett RT, Brook J, Dann T, Delocla C, Philips O, Cakmak S et al. Association between particulate- and gas-phase components of urban air pollution and daily mortality in eight Canadian cities. Inhal Toxicol 2000; 12: 15–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippmann MToxicological and epidemiological studies of cardiovascular effects of ambient air fine particulate matter (PM2.5) and its chemical components:coherence and public health implications. Crit Rev Toxicol 2014; 44: 299–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito K, Mathes R, Ross Z, Nadas A, Thurston G, Matte TFine particulate matter constituents associated with cardiovascular hospitalizations and mortality in New York city. Environ Health Perspect 2011; 119: 467–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang W, Cao JJ, Tao YB, Dai LZ, Lu SE, Hou B et al. Seasonal variation of chemical species associated with short-term mortality effects of PM2.5 in Xi'an, a central city in China. Am J Epidemiol 2012; 175(6): 556–566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Son JY, Lee JT, Kim KH, Jung K, Bell MLCharacterization of fine particulate matter and associations between particulate chemical constituents and mortality in Seoul, Korea. Environ Health Perspect 2012; 120: 872–878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacks JD, Ito K, Wilson WE, Neas LMImpact of covariate models on the assessment of the air pollution-mortality association in a single- and multipollutant context. Am J Epidemiol 2012; 176(7): 622–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mostofky E, Schwartz J, Coull BA, Koutrakis P, Wellenius GA, Suh HH et al. Modeling the association between particle constituents of air pollution and health outcomes. Am J Epidemiol 2012; 176: 317–326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostro B, Tobias A, Querol X, Alastuey A, Amato F, Pey J et al. The effects of particulate matter sources on daily mortality: a case-crossover study of Barcelona, Spain. Environ Health Perspect 2011; 119: 1781–1787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lall R, Ito K, Thurston GDDistributed lag analyses of daily hospital admissions and source-apportioned fine particle air pollution. Environ Health Perspect 2011; 119: 455–460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope CA III, Dockery DWHealth effects of fine particulate air pollution: lines that connect. J Air Waste Manage Assoc 2006; 56: 709–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook RD, Rajagopalan S, Pope CA III, Brook JR, Bhatnagar A, Diez-Roux AV et al. Particulate matter air pollution and cardiovascular disease: an update to the scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2010; 21: 2331–2378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassee FR, Héroux M, Gerlofs-Nijland ME, Kelly FJParticulate matter beyond mass: recent health evidence on the role of fractions, chemical constituents and sources of emission. Inhal Toxicol 2013; 25: 802–812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlesinger RB, Cassee FRAtmospheric secondary inorganic particulate matter: the toxicological perspective as a basis for health effects risk assessment. Inhal Toxicol 2013; 15: 197–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.