Abstract

♦ Background: Despite adverse effects such as constipation, vascular calcification, and hypercalcemia, calcium-based salts are relatively affordable and effective phosphate binders that remain in widespread use in the dialysis population. We conducted a pilot study examining whether the use of a combined magnesium/calcium-based binder was as effective as calcium carbonate at lowering serum phosphate levels in peritoneal dialysis (PD) patients.

♦ Methods: This was a cross-over, investigator-masked pilot study in which prevalent PD patients received calcium carbonate alone (200 mg calcium per tablet) or calcium magnesium carbonate (100 mg calcium, 85 mg magnesium per tablet). Primary outcome was serum phosphate level at 3 months. Analysis was as per protocol.

♦ Results: Twenty patients were recruited, 17 completed the study. Mean starting dose was 11.35 ± 7.04 pills per day of MgCaCO3 and 9.00 ± 4.97 pills per day of CaCO3. Mean phosphate levels fell from 2.13 mmol/L to 2.01 mmol/L (95% confidence interval (CI): 1.76 – 2.30, p = 0.361) in the MgCaCO3 group, and 1.81 mmol/L (95% CI: 1.56 – 2.0, p = 0.026) in the CaCO3 alone group. Six (35%) patients taking MgCaCO3 and 9 (54%) taking CaCO3 alone achieved Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (KDOQI) serum phosphate targets at 3 months. Diarrhea developed in 9 patients taking MgCaCO3 and 3 taking CaCO3. Serum magnesium exceeded 1.4 mmol/L in 5 patients taking MgCaCO3 while serum calcium exceeded 2.65 mmol/L in 3 patients receiving CaCO3. When compared to the initial dose, the prescribed dose at 3 months was reduced by 44% (to 6.41 tablets/day) in the MgCaCO3 group and by 8% (to 8.24 pills per day) in the CaCO3 alone group.

♦ Conclusion: Compared with CaCO3 alone, the preparation and dose of MgCaCO3 used in this pilot study was no better at lowering serum phosphate levels in PD patients, and was associated with more dose-limiting side effects.

Keywords: Phosphate-binders, magnesium calcium carbonate, compliance rates, adverse effects

Current phosphate-lowering strategies include the use of calcium-based dietary phosphate binders. Calcium salt ingestion can lead to constipation, hypercalcemia, and increased vascular calcification rates (1). Sevalemer hydrochloride and lanthanum carbonate, two widely available non-calcium-based binders, are often prohibitively expensive (1,2). Patient compliance with prescribed phosphate-binder regimens is therefore poor, and serum phosphate levels often remain above treatment targets (2). Magnesium salts also bind dietary phosphate, are relatively affordable, and have been shown to be similarly efficacious to calcium-based binders in hemodialysis (HD) patients (3,4). We are aware of only one report examining their use in peritoneal dialysis (PD) patients (5). In 1993, Parsons et al. randomized 50 PD patients to receive one of a combination of MgCO3 and CaCO3 (starting dose 2.2 g each per day, 32 patients), CaCO3 alone (starting dose 2.2 g per day, 10 patients), or an aluminum-based binder (dose not reported, 8 patients). No differences after one year were seen in serum phosphate levels (5). No information on compliance rates, eventual prescribed doses, or side effects was provided.

We wished to conduct a pilot study comparing the effectiveness and patient compliance rates of MgCaCO3 versus CaCO3 in treating hyperphosphatemia in PD patients. Our expectations were that, compared with a calcium only-based binder, a calcium/magnesium-based phosphate binder would be better tolerated, have higher compliance rates, and be more effective at controlling serum phosphate.

Methods

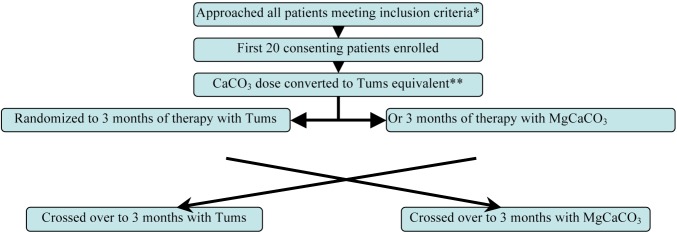

A single-blind, randomized, cross-over study design was used (Figure 1). Written approval to conduct this study was obtained from our institution’s Ethics Review Board, and signed consent obtained from all study participants. Study drugs were MgCaCO3 (Magnebind 300, Nephro-Tech Inc., Shawnee, KS, USA, 85 mg elemental magnesium, 100 mg elemental calcium per tablet) and CaCO3 (Tums, GlaxoSmithKline, Mississauga, ON, Canada, 200 mg elemental calcium per tablet). As a pilot study, and given the lack of literature concerning expected effect size, a sample size calculation was not performed. To minimize pill burden effect, one tablet of MgCaCO3 was considered equivalent to one tablet of CaCO3. Patients were continued on the same dose of CaCO3 as before study enrollment, (or started on an equivalent number of MgCaCO3 pills). Serum phosphate, calcium, and magnesium levels, and pill counts were checked every 6 weeks. The dose of phosphate binder was halved if serum calcium levels exceeded 2.65 mmol/L, if serum magnesium levels exceeded 1.40 mmol/L, or if diarrhea or constipation developed and was deemed drug-related. The treating clinic physician, who was blinded to treatment arm, prescribed calcium carbonate targeting a serum phosphate of less than 1.80 mmol/L. There was no wash-out period before treatment allocation, and no changes were made in PD prescription (standard PD solutions were used, magnesium concentration 0.34 mmol/L, calcium concentration 1.3 mmol/L). All laxatives were discontinued at study enrollment.

Figure 1 —

Study Schema. * Inclusion criteria: prevalent peritoneal dialysis (PD) patients, age >18 years, PO4 >1.80 mmol/L on 2 occasions, CaCO3 was the only PO4 binder. ** At enrollment all patients were taking a CaCO3 preparation containing 500 mg elemental calcium per tablet. This was converted to a Tums (GlaxoSmithKline Inc., Mississauga, ON, Canada) equivalent (either Tums with 200 mg elemental calcium per tablet or Magnebind 300 (Nephro-Tech, Inc., Shawnee, KS, USA) with 85 mg elemental magnesium and 100 mg elemental calcium per tablet).

Statistical Methods

Data was coded and prepared in Microsoft Access database and analyzed using SPSS statistical package version 20 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). Mixed model analysis was used to compare treatment effects after taking into account the correlation between repeated measurements. Primary outcome was serum phosphate after 12 weeks of phosphate binding therapy. Secondary outcomes included serum phosphate at 6 weeks, the numbers of patients achieving Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (KDOQI) guideline targets for serum phosphate after 12 weeks of therapy, pill counts, and adverse effects severe enough to warrant dose reduction.

Results

The first twenty consenting patients were randomized. Seventeen patients completed the study after one received a renal transplant (7 weeks after enrollment in the MgCaCO3 arm), another dropped out in the first week because she did not like the TUMS tablets, and a third died following 2 peritonitis episodes (first episode 8 weeks after enrollment in CaCO3 arm, the second (culminating in the patient’s death) 7 weeks after crossover into the MgCaCO3 arm.

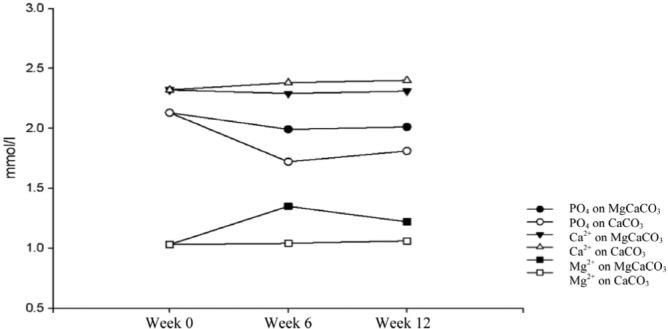

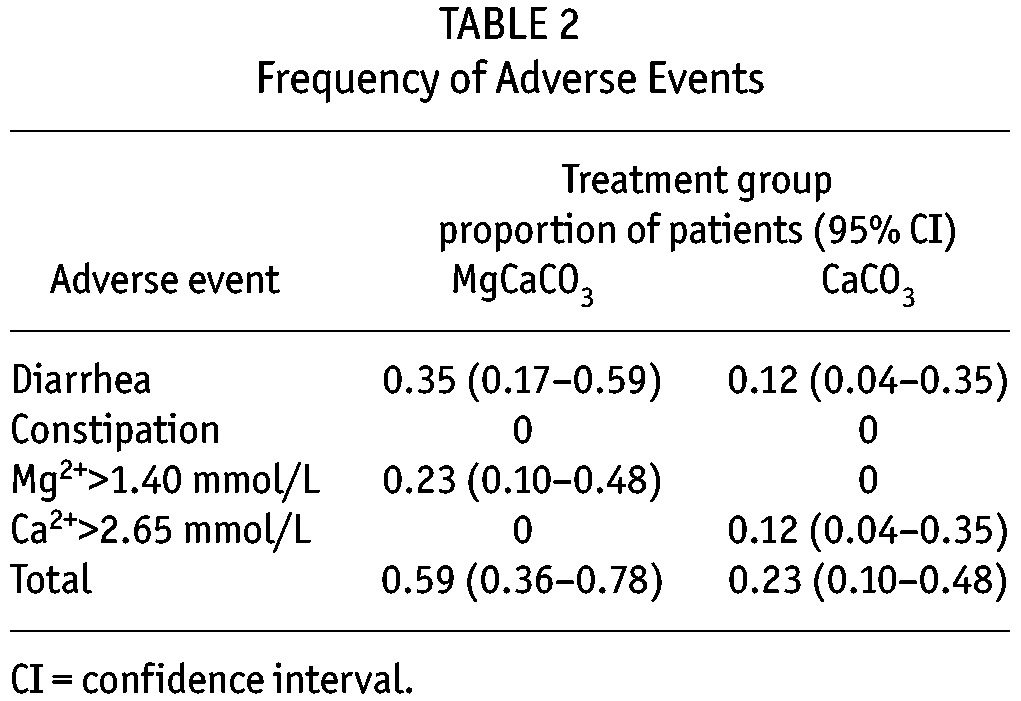

The mean baseline prescribed CaCO3 was 2.28 grams per day (Table 1). Figure 2 highlights the serum phosphate, calcium, and magnesium concentrations after 6 and 12 weeks of therapy. Mixed model analysis revealed MgCaCO3 to be less effective in reducing serum phosphate level (p = 0.043), that CaCo3 associated with higher levels of serum calcium (p = 0.001) and lower levels of magnesium (p = 0.002), and that there was no significant difference in mean parathyroid hormone levels between treatment groups (p = 0.196) (data not shown). KDOQI serum phosphate targets (less than 1.80 mmol/L) were achieved after 12 weeks of therapy in 6 (35%) patients in the MgCaCO3 arm, and 9 (53%) patients in the CaCO3 arm. Table 2 highlights the frequency of adverse events. There were more dose reductions in the MgCaCO3 group because of the development of diarrhea (7 dose reductions in 6 patients) or magnesium levels greater than 1.4 mmol/L (6 dose reductions in 4 patients). By week 12, patients were prescribed 56% of the originally prescribed MgCaCO3 amount (p = 0.004), and 91.6% of the originally prescribed CaCO3 amount (p = 0.149). Pill counts at week 12 were similar between groups (patients ingested 77% of prescribed MgCaCO3 and 76% of prescribed CaCO3).

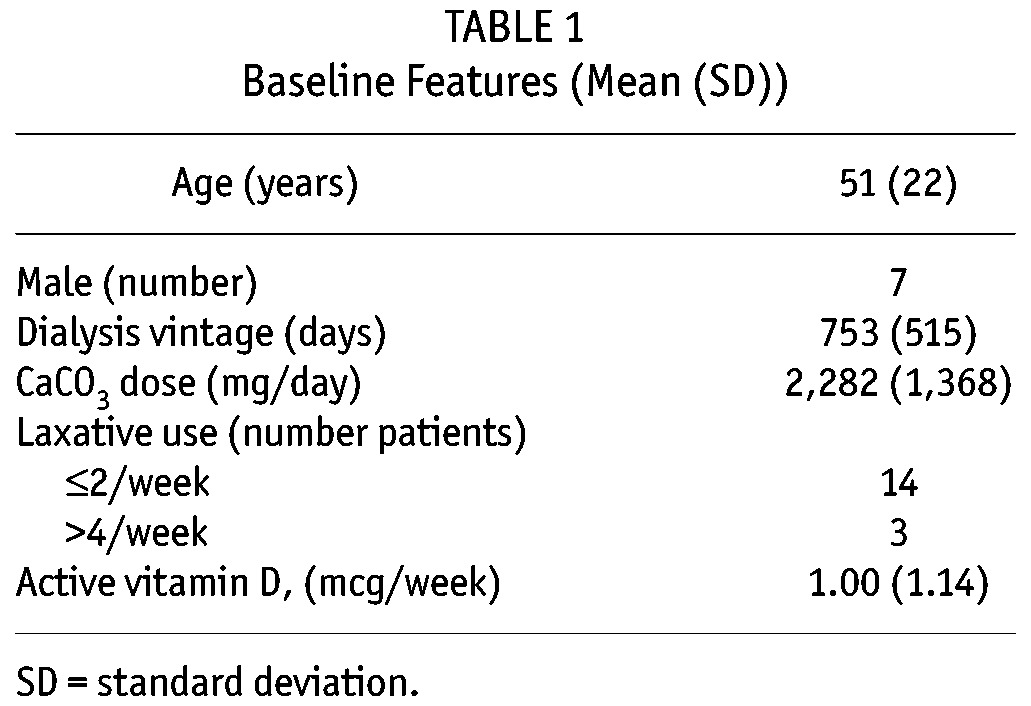

TABLE 1.

Baseline Features (Mean (SD))

Figure 2 —

Mean serum phosphate, calcium, and magnesium concentrations at 0, 6 and 12 weeks. Tums (GlaxoSmithKline, Mississauga, ON, Canada).

TABLE 2.

Frequency of Adverse Events

Discussion

Serum phosphate levels were significantly lower after 12 weeks of therapy with CaCO3 but not with MgCaCO3 in 17 PD patients with uncontrolled hyperphosphatemia. MgCaCO3 (mean starting dose 965 mg elemental magnesium, 1,135 mg elemental calcium per day) was not as well tolerated as CaCO3 alone (mean starting dose 1,800 mg elemental calcium per day). It required more dose reductions primarily because of the development of diarrhea. Previous studies have reported the devel opment of diarrhea in up to 15% of HD patients receiving magnesium-based phosphate binders (3,4). Given that constipation rates are reported to be three times higher in HD than PD patients (6), it is perhaps not surprising that we observed higher rates of diarrhea after administration of a magnesium-based phosphate binder in this study.

Limitations

This was a single-center pilot study enrolling only 20 patients, of whom only 17 completed the study. There was no wash-out period before treatment assignment, and this might have introduced carry-over bias. We started at a large dose based on a pre-study enrollment CaCO3 dose, rather than starting at a lower dose and titrating up to a target phosphate level. Because high levels of magnesium can lead to significant toxicity and even death, we used a conservative upper limit of serum magnesium (7). At our threshold of 1.40 mmol/L, MgCaCO3 doses were reduced six times in four patients. This could have biased against the potential benefits of higher MgCaCO3 doses in patients who might have tolerated higher serum magnesium levels.

Conclusions

Compared with CaCO3, MgCaCO3 was less effective at lowering elevated serum phosphate levels, and required more dose reductions because of the development of diarrhea or elevated magnesium levels in this pilot study of 17 peritoneal dialysis patients.

Disclosures

None of the authors have any financial conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1. Emmett M. A comparison of clinically useful phosphorus binders for patients with chronic kidney failure. Kidney Int 2004; 66:S25–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chiu YW, Teitelbaum I, Misra M, de Leon EM, Adzize T, Mehrotra R. Pill burden, adherence, hyperphosphatemia, and quality of life in maintenance dialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2009; 4(6):1089–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. de Francisco ALM, Leidig M, Covic AC, Ketteler M, Benedyk-Lorens E, Mircescu GM, et al. Evaluation of calcium acetate/magnesium carbonate as a phosphate binder compared with sevelamer hydrochloride in haemodialysis patients: a controlled randomized study (CALMAG study) assessing efficacy and tolerability. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2010; 25(11):3707–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tzanakis IP, Papadaki AN, Wei M, Kagia S, Spadidakis VV, Kallivretakis NE. Magnesium carbonate for phosphate control in patients on hemodialysis. A randomized controlled trial. Int Urol Nephrol 2008; 40(1):193–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Parsons V, Baldwin D, Moniz C, Marsden J, Ball E, Rifkin I. Successful control of hyperparathyroidism in patients on continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis using magnesium carbonate and calcium carbonate as phosphate binders. Nephron 1993; 63(4):379–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yasuda G, Shibata K, Takizawa T, Ikeda Y, Tokita Y, Umemura S, et al. Prevalence of constipation in continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis patients and comparison with hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 2002. June; 39(6):1292–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jung GJ, Gil HW, Yang JO, Lee EY, Hong SY. Severe hypermagnesemia causing quadriparesis in a CAPD patient. Perit Dial Int 2008. Mar-Apr; 28(2):206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]