Abstract

♦ Introduction: Peritonitis remains a common complication of peritoneal dialysis (PD). Although representing only 1 – 12% of overall peritonitis in dialysis patients, fungal peritonitis (FP) is associated with serious complications, including technique failure and death. Only scarce data have been published regarding FP outcomes in modern cohorts in North America. In this study we evaluated the rates, characteristics and outcomes of FP in a major North American PD center.

♦ Methods: We conducted a retrospective cohort study including all fungal peritonitis episodes among peritoneal dialysis patients followed in a large PD center between January 2000 and February 2013. Our pre-specified endpoints included rates of FP, characteristics, outcomes and determinants of death.

♦ Results: Thirty-six episodes of FP were identified during the follow-up period (one episode per 671 patient-months), representing 4.5% of the total peritonitis events. Patients’ mean age and peritoneal dialysis vintage were 61.3 ± 15.5 and 2.9 (1.5 – 4.8) years, respectively. Of the 36 episodes of FP, seven (19%) resulted in death and 17 (47%) led to technique failure with permanent transfer to hemodialysis. Surprisingly, PD was eventually resumed in 33% of cases with a median delay of 15 weeks (interquartile range 8 – 23) between FP and catheter reinsertion. In a univariable analysis, a higher Charlson comorbidity index (Odds ratio [OR] 3.25 per unit increase, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.23 – 8.58) and PD fluid white blood cell (WBC) count greater than 3,000/mm3 at presentation (OR 6.56, 95% CI 1.05 – 40.95) predicted death.

♦ Conclusion: While fungal peritonitis is still associated with a high frequency of death and technique failure, onethird of our patients eventually returned to PD. Patients with a high burden of comorbidities appear at higher risk of death. We postulate that the high mortality associated with FP is partially related to the severity of comorbidity among patients with FP, rather than the infection per se. Importantly, PD can be resumed in a significant proportion of cases.

Keywords: Peritoneal dialysis, fungal peritonitis, technique survival, death

Peritonitis is a common complication of peritoneal dialysis (PD). Although representing only a minority of cases, fungal peritonitis (FP) is associated with serious complications (1–8). Previous reports have found that following FP, technique failure (15 – 85%) and death (5 – 55%) are particularly frequent (1–6,9). Survival has been showed to be improved with early catheter removal (1), however, once the PD catheter is removed, the proportion of patients eventually resuming PD remains relatively low (5 – 15%) (4). On the other hand, antibiotic use, especially when given for a bacterial peritonitis, is a known risk factor for FP. Fungal prophylaxis during bacterial peritonitis therapy is therefore advocated by different investigators (10), although benefits of such prophylaxis have been inconsistent in the literature (7,11–13).

While PD is conducted and promoted internationally, most of the recent reports on FP were performed by groups from the Asian-Pacific region (1,4). Whether or not the results of these studies can by applied to a North American PD population remains uncertain.

In this study, we aim to evaluate rates, characteristics, treatments and outcomes of FP peritonitis in a large North American PD unit between 2000 and 2013. Our prespecified endpoints include the evaluation of risk factors associated with death secondary to FP and the assessment of patients who subsequently resumed PD after FP.

Methods

Study Population

We conducted a retrospective single-center descriptive study which included all episodes of FP among PD patients followed at University Health Network between January 2000 and March 2013. Outcomes were recorded until May 2013. Patients admitted for peritonitis but belonging to another PD program and those from our program who had an episode of peritonitis in another country where data could not be tracked were excluded.

Data Collection

Fungal peritonitis events were retrieved using Monthly peritonitis reports, which collects baseline information about all peritonitis within our program. Patients’ demographics, comorbidities and previous antibiotic use were collected from electronic records and clinic charts. Individual comorbidities were combined into a Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI). This index assigns points to several medical conditions in order to determine a global comorbidity score. Higher scores have been associated with mortality (14). The CCI has been validated in dialysis patients (15). Peritonitis microbiological characteristics, treatments and outcomes were also gathered from manual charts and electronic records reviews.

Definitions

Fungal peritonitis was defined by the presence of a positive yeast culture with one of the two subsequent: peritoneal effluent leucocyte count > 100 cellules/mm3 or clinical symptoms of peritonitis (abdominal pain, cloudy dialysate, fever). Death was considered secondary to the FP when both events occurred during the same hospitalization in a patient with active peritonitis or its related complications at the time of death or if the death occurred within four weeks of FP presentation. Permanent transfer to hemodialysis (HD) was defined in any patient for whom no transfer back to PD was organized within the twelve months after the FP or at the end of the study period. Resumption of PD was defined by the placement of a new PD catheter and its successful use after a FP episode. A patient with more than one episode of FP during the study period was considered as two distinct FP events in the analysis of baseline characteristics and outcomes.

Statistical Analysis

Data are reported as absolute number and percentage for categorical variables, mean ± standard deviation for normally distributed continuous variables, and median and interquartile range for non-normally distributed continuous variables. Comparisons between survivors and non-survivors were performed using Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables, and t-tests or Wilcoxon rank sum test for normally or non-normally distributed variables, respectively. In an exploratory analysis, univariable predictors of death secondary to FP were examined using logistic regression. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata IC, version 12 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). A two-tailed p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Approval for the study was received from the research ethics board at the University Health Network.

Results

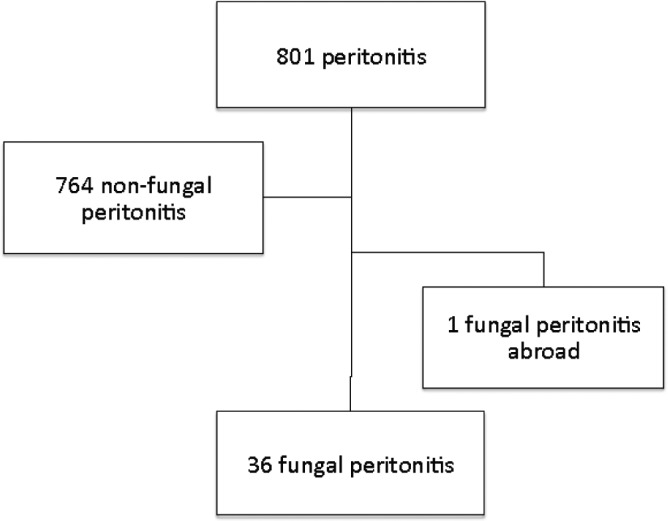

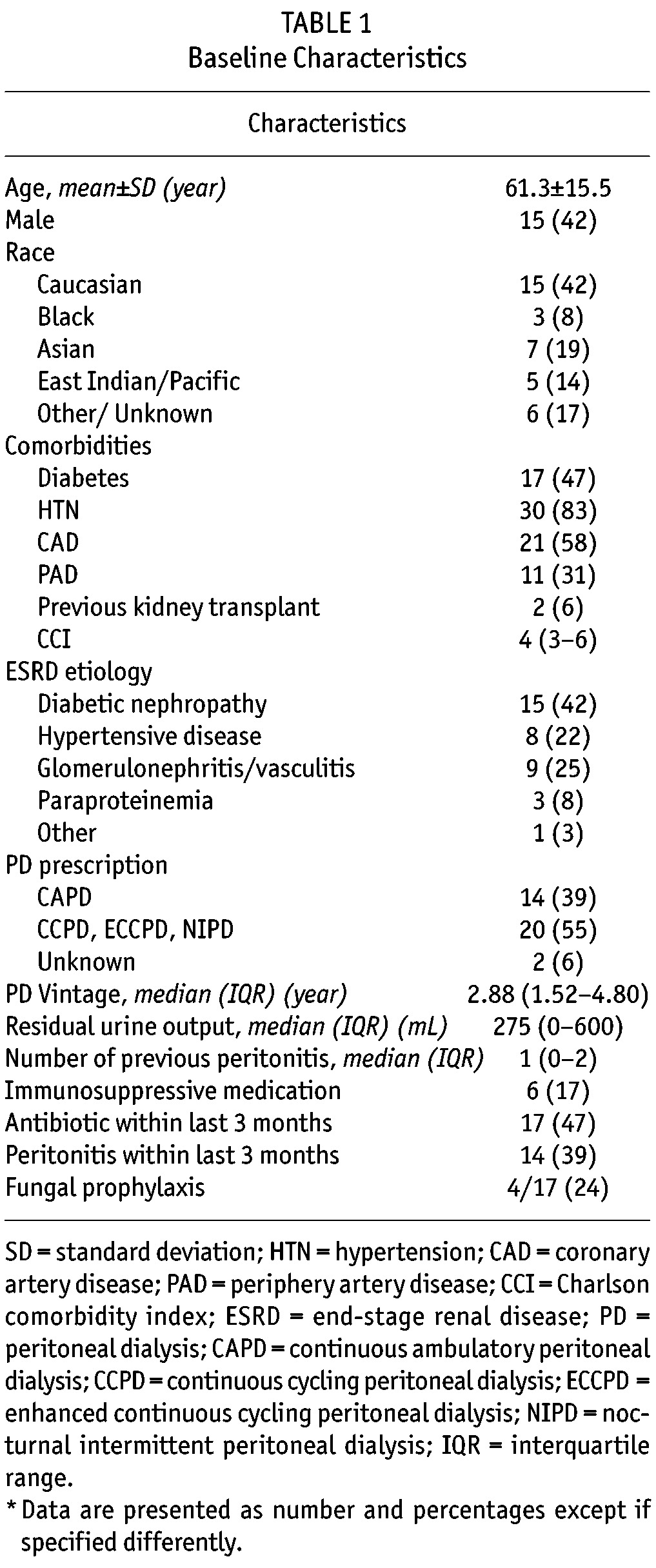

Thirty-six episodes of FP were identified, in 35 patients, among 801 peritonitis over a follow-up period of 2014 patient-years (Figure 1). Hence, FPs represented 4.5% of the total peritonitis events. The FP rate was one per 671 patient-months (1 per 55 patient-years or 0.018 episodes per year). Patients’ characteristics at the time of FP are presented in Table 1. At time of FP, mean age was 61.3 ± 15.5 years and median PD vintage was 2.9 years (1.5 – 4.8). The median CCI was 4 (3 – 6). Seventeen patients (47%) received antibiotics within the 3 months before FP. Among them, four (24%) patients also received antifungal prophylaxis.

Figure 1 —

Flow chart.

TABLE 1.

Baseline Characteristics

Complete clinical and microbiological characteristics at time of FP presentation are displayed in Table 2. All patients presented with cloudy dialysate, 29 (81%) had abdominal pain and 7 (19%) had fever. Median peritoneal effluent leucocyte count at presentation was 1,755 cell/mm3 (interquartile range [IQR] 819 – 4100). All FPs were caused by candida organisms. Candida albicans was identified in 17 (46%) patients and candida parapsilosis in 13 (36%) patients. A majority of patients (64%) were treated with fluconazole as antifungal therapy. Sensitivity testing to antifungal therapy was not routinely performed. No specific seasonal FP outbreak patterns were identified in our cohort.

TABLE 2.

Clinical and Microbiological Characteristics at Fungal Peritonitis Presentation

The PD catheter was removed in 30 (83%) patients with a median delay between presentation with FP and catheter removal of 3 days (IQR 3 – 6). The median time to fungi identification in the peritoneal smear or culture was one day (IQR 0 – 1) among the 24 cases for which the data was available. All catheters were removed after identification of a yeast organism. Of the six patients without catheter removal, three were unsuitable for surgery and two received palliative treatment. The three others survived their FP episode and were kept on PD. One of them had no vascular access allowing HD, while the two others had mild clinical symptoms, only one positive fungal culture, normal peritoneal effluent leucocytes count and rapidly improved with antifungal therapy alone.

Among our 36 patients with FP, seven (19%) died, 17 (47%) were permanently transferred to HD, 3 (8%) stayed on long-term PD despite FP and 9 (25%) eventually resumed PD (Figure 2). Among this last group, the median time to catheter reinsertion was 15 weeks (8 – 23). Among the patients with FP-related death, six patients still had active peritonitis at time of death and one patient had a sudden death while still in hospital less than four weeks after FP presentation.

Figure 2 —

Outcomes of fungal peritonitis: death (7 patients), definitive transfer to hemodialysis (17 patients), resumption or continuation of PD (12 patients).

When examining baseline characteristics stratified by survivor status (Table 3), patients with FP-related death had a higher burden of comorbidity, including higher prevalence of diabetes, coronary artery disease and periphery artery disease. Median CCI score was 6 (IQR 5 – 7) for non-survivors compared to 4 (IQR 3 – 5) for survivors (p = 0.004). PD vintage tended to be longer among patients with FP-related death compared to the survivors (5.0 years [IQR 2.2 – 7.4| vs 2.5 years [IQR 1.2 – 4.3], p = 0.069). Furthermore, peritoneal effluent leucocyte count at the time of presentation was higher among patients who died of FP (3,300 [IQR 2,000 – 7,150]) compared to those who survived (1,300 [IQR 709 – 3,500]), p = 0.044). There was no significant difference in the time to catheter removal, with a median delay of 3.5 days (3 – 6) for the survivors and 3.0 days (2 – 4.5) for the non-survivors (p = 0.400).

TABLE 3.

Characteristics Stratified by Survivor and Non-survivor Status

In an exploratory univariable analysis, we evaluated the factors associated with FP-related death in our cohort (Table 4). Comorbidity burden as expressed by CCI (Odds ratio [OR] 3.25 per point increase, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.23 – 8.56, p = 0.017) and peritoneal effluent leucocyte count at presentation > 3,000 cell/mm3 (OR 6.56, 95% CI 1.05 – 40.95, p = 0.044) were associated with higher risk of FP-related death, as was PD vintage, but without reaching statistical significance (OR 1.45 per year, 95% CI 0.99 – 2.05, p = 0.054). Although not significant, presence of residual urine output seemed protective (OR 0.14, 95% CI 0.01 – 1.27, p = 0.080). Because of the small number of events, a multivariable analysis could not be performed.

TABLE 4.

Factors Associated with Death with Fungal Peritonitis (n=7)

Among the seven non-survivors, palliative care was initiated in two patients because of general frailty and sickness. Another patient developed FP after several months in the intensive care unit due to a chronic neurologic condition from which he subsequently died.

Our cohort includes two cases of FP in women with uterine prolapse and pessaries. Both cases were caused by candida parapsilosis and responded well to antifungal therapy. One of these two patients experienced two episodes of FP. The PD catheter was removed after the first episode and the patient received temporary HD for 13 weeks before reinsertion of another PD catheter. The second FP episode occurred within two months after PD re-initiation and the patient was then permanently transferred to HD. Whether or not the pessary was associated with these episodes is unknown. However, vaginal candidiasis has anecdotally been described in association with FP (16).

Discussion

In this study, we described 36 cases of fungal peritonitis (FP) in a North American PD center, representing a FP rate of one per 55 patient-year (0.018 episode per year) of follow-up. Of these episodes, seven (19%) led to the patient’s death, while 12 (33%) were in patients who eventually resumed (or stayed on) PD. In an exploratory logistic regression, CCI and peritoneal effluent leucocyte count > 3,000 cell/mm3 at time of presentation were associated with FP-related death.

Over a follow-up of 2,014 patient-years, our unit encountered 801 peritonitis, 36 (4.5%) of which were caused by a fungal organism. Similar rates have been reported in previous publications, both for FP incidence per patient-year and proportion of global peritonitis (1,2,7,8).

All cases of FPs were due to candida organisms. A small case series of nine FP from another North American center also reported candida species FPs only (2), while more than 90% of FPs were caused by candida species in a report from the United Kingdom (7). In contrast, most reports from Eastern countries and South American countries have described the presence of non-candida FPs, including Aspergillus and Penicillium species (1,4,5,11,17–19). Tropical climate might increase the likelihood of noncandida species with reports from Australia describing up to 32% of non-candida FPs. Seasonal variation is also reported (4,19). In contrast, no seasonal variation was found in our cohort of patients in a large North American city with a continental climate.

In our cohort, patients who died of a FP-event had a higher burden of comorbidity, tended to have longer PD vintage and less residual urine output. Similar factors were identified in a larger Korean cohort (1). Specifically in our cohort, two of the seven non-survivors underwent palliative care at the time of FP due to a high burden of comorbidities while another FP occurred in a patient with a prolonged intensive care unit course who eventually also became palliative. Hence, we speculate that the risk of death associated with FP is in part related to a high burden of comorbidities among frail PD patients rather than the FP episode per se.

Similar to what was reported by Miles et al. (4), time to catheter removal was not different among survivors and non-survivors in our cohort with a median delay of 3.5 and 3.0 days, respectively. Interestingly, the median delay to catheter removal was overall longer than the 24h previously identified as a risk factor by Chang et al. (1).

Almost a third of our patients were able to return to or stay on PD after an episode of FP. This is more than reported in most publications where the proportion of subsequent PD resumption is typically between 0 – 20% (1,4,8). The median time to catheter reinsertion after a FP episode was 15 weeks with the longest delay to catheter reinsertion being more than six months, enhancing the importance of modality discussion even when a patient has been on HD for many weeks. This successful rate of PD return is probably partly attributable to our strong multidisciplinary team, which follows patients placed on temporary HD and systematically reassesses the possibility of a transition back to PD.

Our unit practice in regards to FP is normally prompt PD catheter removal in combination with antifungal therapy, usually fluconazole as first line therapy, which is based on International Society for Peritoneal Dialysis (ISPD) guidelines (20). However, we identified three patients successfully treated with antifungal therapy alone without catheter removal. In two cases, mild symptoms and reassuring microbiological finding led to catheter preservation while the third patient stayed on PD because of the lack of any vascular access for HD. Although generally not suggested, medical treatment of FP without catheter removal has also been shown to be effective in certain circumstances (5,21).

Antibiotic treatment preceded FPs in almost half of the cases. Most of the time, bacterial peritonitis was the reason leading to antibiotic prescription. Antibiotic treatment in the previous three months is a well-known risk factor for FP (1,3,22) which has led the ISPD to recommend antifungal prophylaxis in units with higher rates of FP. Benefits of antifungal prophylaxis have also been shown in a randomized control trial (11) where fluconazole administration significantly reduced the number of FP after a bacterial peritonitis or exit site episode. Our unit has been routinely using nystatin for antifungal prophylaxis at the time of any prolonged antibiotic administration since 2005. Despite this practice, antifungal prophylaxis was identified with documented prescription in only four patients out of 17 who received antibiotics (24%) during the overall study period (from 2000 to 2013) and four out of eight (50%) since 2005. A few patients might have received antifungal prophylaxis without appropriate documentation in the chart, which might contribute to this low prophylaxis rate.

This study has limitations. First, the retrospective nature of the study might have led to incomplete data collection. However, great attention has been taken with the review of both electronic and manual charts and very few data were missing. Because of the relative rarity of FP, our total number of episodes remains quite small, despite a long follow-up time. Furthermore, the evaluation of the factors associated with FP-related death was even more limited by the sample size, allowing us to do only exploratory univariable analysis. Finally, we did not have access to specific characteristics of patients with non-fungal peritonitis nor could we compare their outcomes to those of patients with FP. Despite these limitations, we believe that this study is important considering its unique description of FP in a large PD North American unit.

In conclusion, this study showed that although fungal peritonitis is still associated with a significant risk of death and technique failure, about one-third of our patients could eventually return to PD. Knowing that patients with a high burden of comorbidity appeared at higher risk of death, we postulate that the high mortality associated with FP is partially related to the severity of comorbidity among patients with FP, rather than the infection per se. Importantly, PD was resumed in a significant proportion of our cases, which enhances the importance of reassessing the suitability for PD after FP.

Disclosure

Dr. Bargman is a consultant for Amgen, Baxter Healthcare and Otsuka and is a speaker for Amgen and DaVita Healthcare Partners.

Acknowledgments

Dr. A.C. Nadeau-Fredette holds salary support from UHN-Baxter Home Dialysis fellowship.

REFERENCES

- 1. Chang TI, Kim HW, Park JT, Lee DH, Lee JH, Yoo TH, et al. Early catheter removal improves patient survival in peritoneal dialysis patients with fungal peritonitis: Results of ninety-four episodes of fungal peritonitis at a single center. Perit Dial Int 2011; 31:60–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Levallois J, Nadeau-Fredette AC, Labbe AC, Laverdiere M, Ouimet D, Vallee M. Ten-year experience with fungal peritonitis in peritoneal dialysis patients: Antifungal susceptibility patterns in a north-american center. Int J Infect Dis 2012; 16:e41–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Matuszkiewicz-Rowinska J. Update on fungal peritonitis and its treatment. Perit Dial Int 2009; 29 Suppl 2:S161–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Miles R, Hawley CM, McDonald SP, Brown FG, Rosman JB, Wiggins KJ, et al. Predictors and outcomes of fungal peritonitis in peritoneal dialysis patients. Kidney Int 2009; 76:622–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Oygar DD, Altiparmak MR, Murtezaoglu A, Yalin AS, Ataman R, Serdengecti K. Fungal peritonitis in peritoneal dialysis: Risk factors and prognosis. Ren Fail 2009; 31:25–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Prasad KN, Prasad N, Gupta A, Sharma RK, Verma AK, Ayyagari A. Fungal peritonitis in patients on continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis: A single centre indian experience. J Infect 2004; 48:96–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Davenport A, Wellsted D, Pan Thames Renal Audit Peritoneal Dialysis G. Does antifungal prophylaxis with daily oral fluconazole reduce the risk of fungal peritonitis in peritoneal dialysis patients? The pan thames renal audit. Blood Purif 2011; 32:181–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Khan FY, Elsayed M, Anand D, Abu Khattab M, Sanjay D. Fungal peritonitis in patients undergoing continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis in qatar. J Infect Dev Ctries 2011; 5:646–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wang AY, Yu AW, Li PK, Lam PK, Leung CB, Lai KN, et al. Factors predicting outcome of fungal peritonitis in peritoneal dialysis: Analysis of a 9-year experience of fungal peritonitis in a single center. Am J Kidney Dis 2000; 36:1183–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Piraino B, Bernardini J, Brown E, Figueiredo A, Johnson DW, Lye WC, et al. Ispd position statement on reducing the risks of peritoneal dialysis-related infections. Perit Dial Int 2011; 31:614–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Restrepo C, Chacon J, Manjarres G. Fungal peritonitis in peritoneal dialysis patients: Successful prophylaxis with fluconazole, as demonstrated by prospective randomized control trial. Perit Dial Int 2010; 30:619–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wong PN, Lo KY, Tong GM, Chan SF, Lo MW, Mak SK, et al. Prevention of fungal peritonitis with nystatin prophylaxis in patients receiving capd. Perit Dial Int 2007; 27:531–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Williams PF, Moncrieff N, Marriott J. No benefit in using nystatin prophylaxis against fungal peritonitis in peritoneal dialysis patients. Perit Dial Int 2000; 20:352–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987; 40:373–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hemmelgarn BR, Manns BJ, Quan H, Ghali WA. Adapting the charlson comorbidity index for use in patients with esrd. Am J Kidney Dis 2003; 42:125–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Castillo AA, Lew SQ, Smith A, Whyte R, Bosch JP. Vaginal candidiasis: A source for fungal peritonitis in peritoneal dialysis? Perit Dial Int 1998; 18:338–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Unal A, Kocyigit I, Sipahioglu MH, Tokgoz B, Oymak O, Utas C. Fungal peritonitis in peritoneal dialysis: An analysis of 21 cases. Int Urol Nephrol 2011; 43:211–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Predari SC, de Paulis AN, Veron D, Zucchini A, Santoianni JE. Fungal peritonitis in patients on peritoneal dialysis: Twenty five years of experience in a teaching hospital in argentina. Rev Argent Microbiol 2007; 39:213–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Baer R, Killen JP, Cho Y, Mantha M. Non-candidal fungal peritonitis in far north queensland: A case series. Perit Dial Int 2013; 33(5):559–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Li PK, Szeto CC, Piraino B, Bernardini J, Figueiredo AE, Gupta A, et al. Peritoneal dialysis-related infections recommendations: 2010 update. Perit Dial Int 2010; 30:393–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Boer WH, van Ampting JM, Vos P. Successful treatment of eight episodes of candida peritonitis without catheter removal using intracatheter administration of amphotericin b. Perit Dial Int 2007; 27:208–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lo SH, Chan CK, Shum HP, Chow VC, Mo KL, Wong KS. Risk factors for poor outcome of fungal peritonitis in chinese patients on continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. Perit Dial Int 2003; 23 Suppl 2:S123–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]