The role of antibodies against neuronal surface and synaptic proteins, which identify a group of encephalitides that usually improve with immunotherapy,1 is not fully understood and neuropathology may help elucidate the immune mechanism involved.2,3 Recently, antibodies against dipeptidyl-peptidase-like protein-6 (DPPX), an auxiliary subunit of Kv4.2 potassium channels involved in signal transduction, were identified in 7 patients with encephalitis.4,5 We report the neuropathologic features of a new patient.

Case report.

A 52-year-old man developed anorexia, weight loss, abdominal pain, and diarrhea. Extensive gastrointestinal studies failed to find a cause of his symptoms. One month later, abdominal pain and diarrhea spontaneously subsided, and he became progressively confused and aggressive, exhibiting delusions, visual hallucinations, polydipsia, polyuria, and exaggerated startle response to sounds.

At examination, the patient had a Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score of 18/30, frontal and dysexecutive symptoms, simultanagnosia, apraxia of the eyelids, and myoclonus. The rest of the examination was unremarkable. Routine blood analysis, microbiologic and autoimmune studies, including analysis of onconeuronal antibodies, and brain MRI were unremarkable. CSF examination showed 22 × 106/L lymphocytes (normal ≤ 5 × 106/L), positive immunoglobulin G (IgG) oligoclonal bands, and an IgG index of 1.0 (normal <0.7). He received a course of IV methylprednisolone (1,000 mg/day × 5 days) with transient improvement lasting less than 1 month followed by progression to mutism and immobility. He was then started on oral prednisone (64 mg/day) and improved again. MMSE was 15/30 at 3 months and 24/30 at 6 months. One year later, when he was off prednisone, there was a relapse of neurologic symptoms with confusion, agitation, and cognitive decline. In a few weeks, he became bedridden and died from bronchopneumonia. Brain examination revealed segmental CA1 (Sommer sector) sparing neuronal loss in the hippocampus (figure, A) and patchy, irregularly distributed neuronal loss in subiculum, amygdala, cingulum, and temporo-occipital cortex. This was associated with reactive astrogliosis, microglial activation with HLA-DR expression, and scattered parenchymal CD8-positive T cells (figure, C), some in close contact with apparently intact neurons (figure, D, inset), less frequent CD4-positive T cells, and isolated CD20-positive B cells intermingled with more numerous CD3-positive T cells in perivascular location. No plasma cells or deposits of complement were identified. Brainstem showed mild neuronal loss in locus ceruleus, gliosis of central gray matter and nuclei propii of basis pontis, and microglial activation in pons and medulla oblongata. There were scattered CD8-positive T cells in medulla oblongata, forming small nodules. Cerebellar cortex exhibited focal Purkinje cell loss with isolated axonal swellings (torpedoes) in granule cell layer and segmental reduction of apical Purkinje cell arborization, while dentate nucleus showed gliosis, microglial activation, and occasional CD8-positive T cells in the white matter. There were rare neurofibrillary tangles in the hippocampus, but no senile plaques, synuclein inclusions, or TDP43 aggregates.

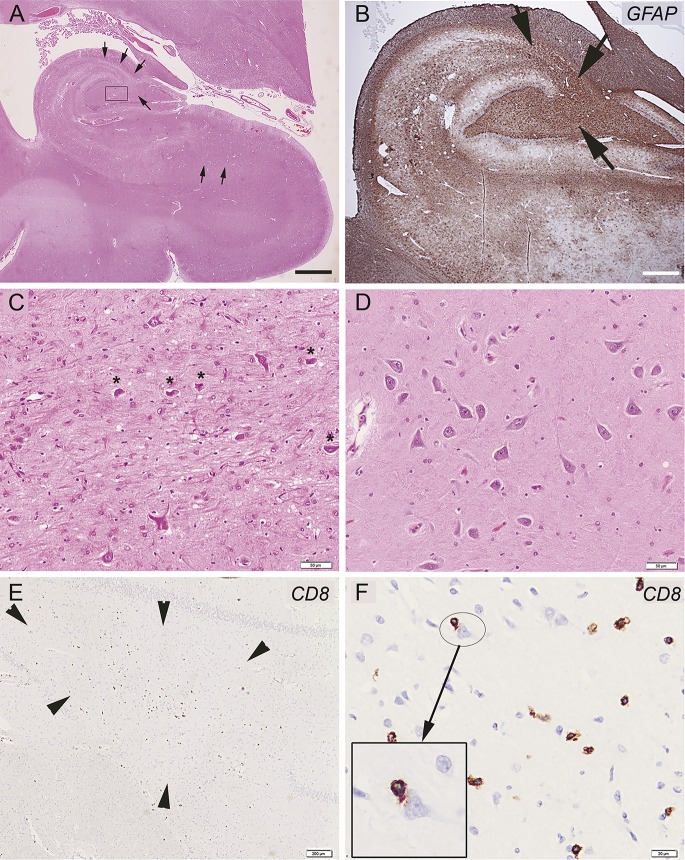

Figure. Illustrative images of hippocampal alterations in a patient with anti-DPPX antibodies.

(A) Low magnification of hippocampus reveals segmental neuronal loss in CA4 and CA3 sectors and patchy, irregularly distributed neuronal loss in subiculum and its transition to entorhinal cortex (most affected regions indicated by arrows), associated with prominent gliosis, as highlighted by glial fibrillary acidic protein immunohistochemistry in B (brown signal and arrows in CA4 and CA3 sector). (C) Higher magnification of the hippocampal findings in CA4 sector (square in A) shows prominent astrogliosis with few remaining, shrunken neurons (asterisks). (D) Normal-appearing CA4 sector for comparison. (E) Anti-CD8 immunohistochemistry of the end folium of the hippocampus reveals scattered parenchymal T lymphocytes (arrowheads). (F) Anti-CD8 immunochemistry of the temporo-occipital cortex in a higher magnification shows anti-CD8-immunopositive T cells in close contact with a morphologically intact–appearing neuron (inset). Scale bar in A represents 3 mm and 1.5 mm in B, 50 μm in C and D, 200 μm in E, and 20 μm in D.

Based on the relapsing history of neurologic symptoms and postmortem studies suggestive of encephalitis, his CSF was re-evaluated and antibodies against DPPX were confirmed by immunofluorescence on HEK293 cells transfected with the antigen.4

Discussion.

We report neuropathologic findings in a patient with anti-DPPX antibodies who developed several features similar to those reported in anti-DPPX encephalitis, including prodromic severe diarrhea, prominent psychiatric symptoms, exaggerated startle response, CSF pleocytosis, and relapses when immunotherapy was discontinued.4,5 The most relevant finding was the neuronal cell loss in CA4 and CA3 sectors of the hippocampus along with mild perivascular and parenchymal inflammatory infiltrates mainly composed of CD8-positive T cells. We do not have complete details of the clinical evolution at the last relapse so we cannot rule out hippocampal damage secondary to agonic events; however, the preservation of the pyramidal neurons in the Sommer sector of the hippocampus does not support hypoxia as the cause of the neuropathologic changes.

There are few neuropathology studies of encephalitides associated with antibodies against surface antigens. Unlike the present case, the brains of patients with anti-NMDAR encephalitis display abundant plasma cells and immunoblasts in the parenchyma, whereas T and B lymphocytes are mostly confined in the perivascular spaces.2 Our findings resemble those found in a few patients with encephalitis and antibodies to VGKC complex proteins (likely LGI1 in most cases), where there was neuronal loss, particularly in the CA4 sector of the hippocampus, along with variable degrees of CD8-positive T cells and complement deposition.3,6,7 The latter was not observed in our patient. Taken together, our findings suggest that neuronal loss, with possible contribution of T-cell-mediated inflammation, may occur in encephalitides associated with potentially pathogenic antibodies against neuronal surface antigens.

Footnotes

Author contributions: Study concept and design: Dr. Stokin. Acquisition of data: Dr. Stokin, Dr. Popović, Dr. Gelpi, Dr. Kogoj. Analysis and interpretation of data: Dr. Stokin, Dr. Popović, Dr. Gelpi, Dr. Kogoj, Dr. Graus. Drafting/revising the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content: Dr. Stokin, Dr. Popović, Dr. Gelpi, Dr. Kogoj, Dr. Dalmau, Dr. Graus.

Study funding: Supported by NIH (RO1NS077851 to J.D.), Fundació la Marató TV3 (to J.D.), Fundacion Carlos III (FIS, PI11/01780 to J.D.), and Euroimmun (to J.D.).

Disclosure: G. Stokin, M. Popović, and E. Gelpi report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. A. Kogoj is deceased and disclosures are not included for this author. J. Dalmau reports a patent application for the use of NMDA receptor as an autoantibody test. F. Graus reports no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Go to Neurology.org for full disclosures.

References

- 1.Lancaster E, Dalmau J. Neuronal autoantigens: pathogenesis, associated disorders and antibody testing. Nat Rev Neurol 2012;8:380–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martinez-Hernandez E, Horvath J, Shiloh-Malawsky Y, Sangha N, Martinez-Lage M, Dalmau J. Analysis of complement and plasma cells in the brain of patients with anti-NMDAR encephalitis. Neurology 2011;77:589–593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bien CG, Vincent A, Barnett MH, et al. Immunopathology of autoantibody-associated encephalitides: clues for pathogenesis. Brain 2012;135:1622–1638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boronat A, Gelfand JM, Gresa-Arribas N, et al. Encephalitis and antibodies to dipeptidyl-peptidase-like protein-6, a subunit of Kv4.2 potassium channels. Ann Neurol 2013;73:120–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balint B, Jarius S, Nagel S, et al. Progressive encephalomyelitis with rigidity and myoclonus: a new variant with DPPX antibodies. Neurology 2014;82:1521–1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schultze-Amberger J, Pehl D, Stenzel W. LGI-1-positive limbic encephalitis: a clinicopathological study. J Neurol 2012;259:2478–2480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khan NL, Jeffree MA, Good C, Macleod W, Al-Sarraj S. Histopathology of VGKC antibody-associated limbic encephalitis. Neurology 2009;72:1703–1705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]