Abstract

Ganglioneuroblastoma is an uncommon malignant tumour, and it is extremely rare in adults. A 27-year-old woman was admitted to hospital complaining of commitment left loin pain for 7 months accompanied with fever for 1 day. Computed tomography (CT) scan shows a huge cystic solid mass among the rear of the pancreatic body and tail, inside of the spleen, and the top of the left kidney. Hormone examinations showed that the serum levels of glucocorticoid, aldosterone, norepinephrine, and epinephrine were normal. However, neuron-specific enolase (NSE) was significantly higher (289.46 ng/mL, normal level <16.3 ng/mL). Adrenal mass resection was scheduled. However, intraoperative separation was very difficult and adrenal tumour resection, resection of the pancreatic body and tail, left nephrectomy, and splenectomy were carried out. Pathological diagnosis was ganglioneuroblastoma.

Introduction

Ganglioneuroblastoma is a rare tumour variant of neuroblastoma. The sites of origin of ganglioneuroblastoma include adrenal medulla, extra-adrenal retroperitoneum, posterior mediastinum, the neck, and pelvis.1 More than 90% of all ganglioneuroblastomas are seen in children under 5 years old, and it is rare in adults.2 Only 11 cases have been observed in the adult adrenal glands, and we report here on 1 more adult patient with adrenal ganglioneuroblastoma. Additionally, we reviewed all 11 published adult cases with adrenal ganglioneuroblastoma.

Case report

A 27-year-old woman was admitted to hospital complaining of commitment left loin pain for 7 months accompanied with fever for 1 day. She experienced no hematuria, weight loss, nausea, or diarrhea. She had a Cesarean section 7 months before. She had no history of urologic or chronic medical disorders. Physical examination showed tenderness and percussion pain in the left kidney district. A huge mass was felt on the left side of the abdomen. All routine examinations were normal except for white blood cell count 11.24 × 109/L. The ultrasound examination elucidated an 11.5 × 9.5-cm hypoechoic mass in the left adrenal area.

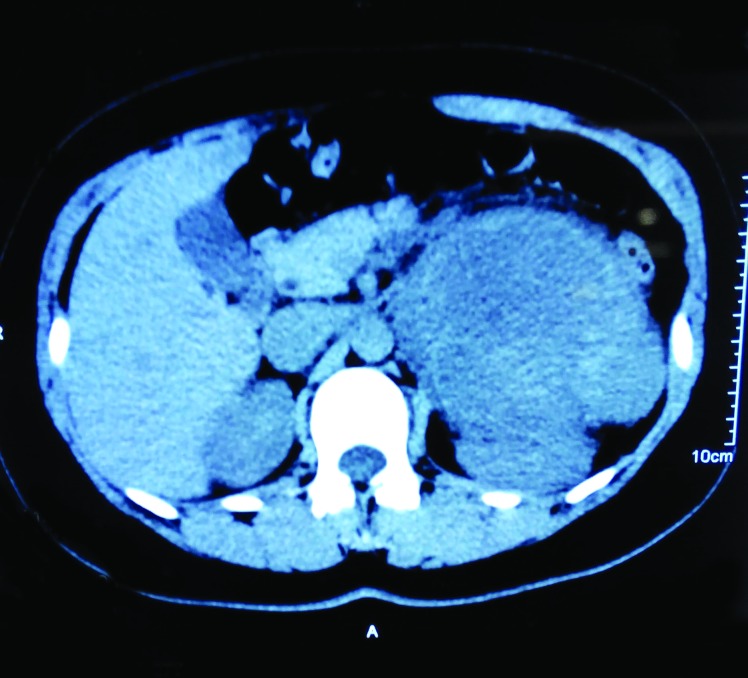

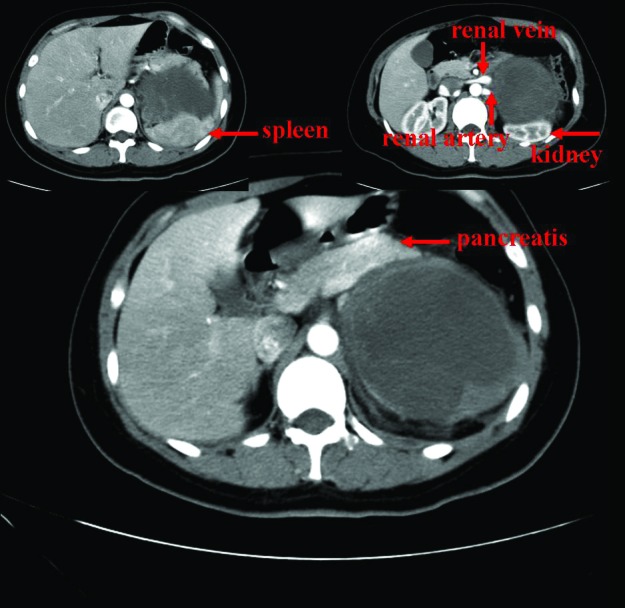

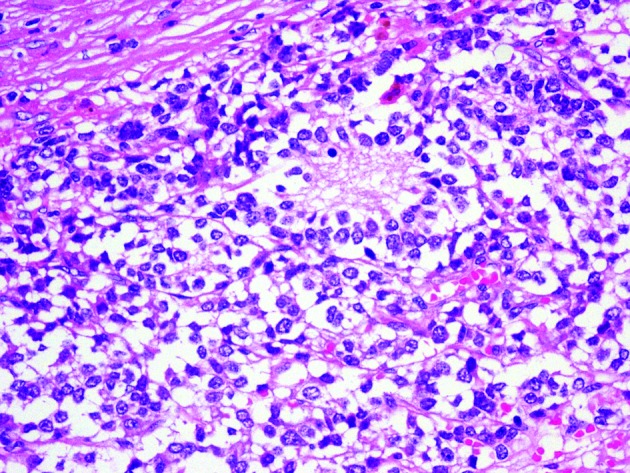

On un-enhanced computed tomography (CT), a cystic solid mass was present among the rear of the pancreatic body and tail, inside of the spleen and the top of the left kidney (Fig. 1). The mass size was 11.4 × 9.4 cm with uneven inner density and visible separation. Enhanced images showed visible enhancement in the solid components and no obvious enhancement in the cystic components (Fig. 2). Boundaries among the mass, renal artery, and spleen were unclear. These findings suggested a pheochromocytoma, but were also compatible with an adrenal malignancy or neurogenic tumour. Hormone examinations showed that the serum levels of glucocorticoid, aldosterone, norepinephrine, and epinephrine were normal. However, neuron-specific enolase (NSE) was significantly higher (289.46 ng/mL, normal level <16.3 ng/mL). Adrenal mass resection was scheduled. However, intraoperative separation was very difficult; therefore, adrenal tumour resection, resection of the pancreatic body and tail, left nephrectomy and splenectomy were carried out. Pathological diagnosis was ganglioneuroblastoma (Fig. 3) and postoperative clinical stage was stage 1.

Fig. 1.

Un-enhanced computed tomography scan showed a large cystic solid mass among the rear of the pancreatic body and tail, inside of the spleen and the top of the left kidney.

Fig. 2.

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan shows a heterogenous soft-tissue mass in the right adrenal gland. The left renal artery and vein are invaded by the lesion.

Fig. 3.

Typical Homer Wrights rosettes are shown and confirmed the diagnosis of ganglione uroblastoma (hematoxylin and eosin stain ×400).

Immunohistochemical studies were positive for chromogranin, synaptophysin and neurofilaments, but negative for desmin and CD99. Because of the patient’s financial and health insurance problem, no chemotherapy and radiation were given after surgery.

Discussion

Ganglioneuroblastoma is an uncommon malignant tumour in the sympathetic nervous system. This neoplasm usually occurs in children, and is extremely rare in adults.3–8 Schipper and colleagues1 reviewed all reported cases of ganglioneuroblastoma in adults 20 years of age or older and only found 50 published adult cases with ganglioneuroblastoma.

We searched English articles for MEDLINE database using the key words “adrenal, adult and ganglioneuroblastoma” to select papers; mixed tumours were excluded. We found 11 cases of adult adrenal ganglioneuroblastoma (Table 1). Butz and colleagues reported the first case of adult adrenal ganglioneuroblastoma in 1940. The mean age at diagnosis of the reported cases was 37.6 (range: 20–59). Males were predominantly affected (8:4). From the 12 cases assessed (including our present case), 5 showed increased urine catechols or its metabolites. However, we believe the function of urine catechols is limited. They could not distinguish ganglioneuroblastoma from pheochromocytoma. In our case, we found the obvious increasing of NSE. Urine catechols may become a promising method to diagnose adult adrenal ganglioneuroblastoma. Unfortunately, we did not re-test NSE after surgery.

Table 1.

Cases of adult adrenal adult ganglioneuroblastoma reported in the literature

| Case | Author | Gender | Age | Tumour size | Hormone | Metastasis | Treatment | Survival |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Butz (1940) | M | 25 | – | – | Liver, para-aortic nodes | None | – |

| 2 | Cameron (1967) | F | 58 | – | Urine catechols↑ | None | CR | 3.5 years, alive |

| 3 | Takahashi (1988) | M | 21 | 8.8 | Urine VMA↑ | Lymph nodes | CR, Ra, C | 8 months, alive |

| 4 | Kishikawa (1992) | M | 29 | 11 | Urine VMA, HVA↑ | Bone | PR, C | – |

| 5 | Koizumi (1992) | F | 47 | 9 | Urine catechols↑ | Bone marrow | None | 3 months, alive |

| 6 | Higuchi (1993) | M | 29 | 11 | Urine catechols↑ | Bone | PR, C | 10 months, alive |

| 7 | Kinya (1995) | M | 35 | 10 | None | None | CR | 24 months, alive |

| 8 | Slapa (2002) | F | 20 | 18 | None | None | CR | 12 months, alive |

| 9 | Koike (2003) | M | 50 | 4.5 | None | (-) | CR | 30 months, alive |

| 10 | Gunlusoy (2004) | M | 59 | 17 | None | Lymph nodes | CR | – |

| 11 | Shugo (2010) | M | 53 | 11 | None | Spine | CR, ad | 30 months, alive |

| 12 | Present case | F | 27 | 11.5 | Neuron-specific enolase (NSE) ↑ | None | CR | – |

C: chemotherapy; Ra: radiation; CR: complete resection; PR: partial resection; VMA: vanilmandelic acid; HVA: homvanillic acid; M: male; F: female.

As an incidentaloma, imaging is difficult to distinguish ganglioneuroblastoma from other adrenal incidentaloma.9 Guo and colleagues10 found that an abdomen CT revealed varied appearances, ranging from predominantly solid mass to predominantly cystic mass with a few thin strands of solid tissue; this variation depends on the number of ganglion cells, their degree of differentiation, and their relationship to immature elements. The authors also believed that magnetic resonance imaging was superior to CT in the detection of diffuse metastases, and these metastases manifested as areas of high signal intensity on T2-weighted images.

It is difficult to make a specific preoperative diagnosis, thus the diagnosis depends on postoperative pathological diagnosis. With regard to the histological features, there is a “Modification of Shimada Classification,” as recommended by the International Neuroblastoma Pathology Committee (INPC). There are 4 ganglioneuroblastoma types: prototype, classical nodular, atypical nodular, and intermixed.

There are 3 kinds of histopathological patterns of neuroblastic tumours: neuroblastoma, ganglioneuroblastoma, and ganglioneuroma. Mizuno and colleagues3 believed that a ganglioneuroblastoma had intermediate malignant potential and was less aggressive than a neuroblastoma. Seven cases (58.3%) showed local lymph nodes or distant metastasis: bone or bone marrow in 4 cases (33.3%), lymph node in 3 (25.0%), and liver metastasis in 1 (8.3%). Mizuno and colleagues3 concluded that larger ganglioneuroblastoma tumours easily develop metastasis. However, we found no direct relationship between tumour size and metastasis.

Treatments of ganglioneuroblastoma include surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation – there is no consensus on best course of treatment. Because of the rarity of ganglioneuroblastoma, a prospective study seems impossible. Survival data are limited. The longest follow-up is only 3.5 years. Schipper and colleagues1 argued that combination therapy benefited patients and that frequent imaging (every 3 months) should also be part of the careful follow-up. Yu and colleauges11 reported that immunotherapy to treat neuroblastomas was successful. However, for ganglioneuroblastoma, the benefit of immunotherapy is unknown.

Conclusion

Ganglioneuroblastoma is an uncommon malignant tumour and is extremely rare in adults. Males were predominantly affected. There was no specific performance on radiologic imaging and it is difficult to make a specific preoperative diagnosis. However, NSE may become a promising method to diagnose adult adrenal ganglioneuroblastoma. Combination therapy and active follow-up are recommended.

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor Quan-Shun Li for the assistance with manuscript preparation. This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 51403074 and 81302206) and the Youth Fund of Health and Family Planning Commission of Jilin Province (No. 2013Q026).

Footnotes

Competing interests: Authors declare no competing financial or personal interests.

This paper has been peer-reviewed.

References

- 1.Schipper MH, van Duinen SG, Taphoorn MJ, et al. Cerebral ganglioneuroblastoma of adult onset: Two patients and a review of the literature. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2012;114:529–34. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2012.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Louis DN. The 2007 WHO classification of tumors of the central nervous system. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;114:97–109. doi: 10.1007/s00401-007-0243-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mizuno S, Iida T, Fujita S. Adult-onset adrenal ganglioneuroblastoma - Bone metastasis two years after surgery: Report of a case. Surg Today. 2010;40:482–6. doi: 10.1007/s00595-008-4084-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lopes RI, Dénes FT, Bissoli J, et al. Laparoscopic adrenalectomy in children. J Pediatr Urol. 2012;8:379–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2011.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thiel EL, Trost BA, Tower RL. A composite pheochromocytoma/ganglioneuroblastoma of the adrenal gland. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2010;54:1032–4. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuyama H, Nii A, Takehara H, et al. Ganglioneuroblastoma, intermixed with opsoclonus-myoclonus syndrome. Pediatr Int. 2012;54:e26–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200X.2012.03597.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koike K, Iihara M, Kanbe M, et al. Adult-type ganglioneuroblastoma in the adrenal gland treated by a laparoscopic resection: Report of a case. Surg Today. 2003;33:785–90. doi: 10.1007/s00595-003-2565-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hiroshige K, Sonoda S, Fujita M, et al. Primary adrenal ganglioneuroblastoma in an adult. Intern Med. 1995;34:1168–73. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.34.1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yip L, Tublin ME, Falcone JA, et al. The adrenal mass: Correlation of histopathology with imaging. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:846–52. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0829-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guo YK, Yang ZG, Li Y, et al. Uncommon adrenal masses: CT and MRI features with histopathologic correlation. Eur J Radiol. 2007;62:359–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2006.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yu AL, Gilman AL, Ozkaynak MF, et al. Anti-GD2 antibody with GM-CSF interleukin-2, and isoretinoin for neuroblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1324–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0911123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]