Abstract

Objective:

SCN8A encodes the sodium channel voltage-gated α8-subunit (Nav1.6). SCN8A mutations have recently been associated with epilepsy and neurodevelopmental disorders. We aimed to delineate the phenotype associated with SCN8A mutations.

Methods:

We used high-throughput sequence analysis of the SCN8A gene in 683 patients with a range of epileptic encephalopathies. In addition, we ascertained cases with SCN8A mutations from other centers. A detailed clinical history was obtained together with a review of EEG and imaging data.

Results:

Seventeen patients with de novo heterozygous mutations of SCN8A were studied. Seizure onset occurred at a mean age of 5 months (range: 1 day to 18 months); in general, seizures were not triggered by fever. Fifteen of 17 patients had multiple seizure types including focal, tonic, clonic, myoclonic and absence seizures, and epileptic spasms; seizures were refractory to antiepileptic therapy. Development was normal in 12 patients and slowed after seizure onset, often with regression; 5 patients had delayed development from birth. All patients developed intellectual disability, ranging from mild to severe. Motor manifestations were prominent including hypotonia, dystonia, hyperreflexia, and ataxia. EEG findings comprised moderate to severe background slowing with focal or multifocal epileptiform discharges.

Conclusion:

SCN8A encephalopathy presents in infancy with multiple seizure types including focal seizures and spasms in some cases. Outcome is often poor and includes hypotonia and movement disorders. The majority of mutations arise de novo, although we observed a single case of somatic mosaicism in an unaffected parent.

The epileptic encephalopathies (EEs) are a group of severe epilepsies that predominantly begin in infancy and childhood. They are characterized by refractory seizures with the child typically experiencing multiple seizure types in the setting of developmental delay or regression; frequent epileptiform activity is seen on EEG studies.1 The genetic etiology of these disorders has become increasingly recognized with de novo mutations in many patients. The prototypic example is Dravet syndrome in which >80% of patients have mutations of the sodium channel α1-subunit gene, SCN1A. Gene discovery in Dravet syndrome has fueled clinical and basic research informing diagnosis and therapeutic approaches.

Recently, the application of next-generation sequencing approaches has led to the identification of multiple new genes for EEs although each is responsible for a small proportion of patients. Once a gene is identified, studies of patients who have a mutation of the same gene facilitate clinical recognition of the phenotypic spectrum of a specific genetic encephalopathy.

Sodium channel genes have emerged as very important in causation of EEs with SCN1A being the most well studied. Mutations of the α-subunit genes SCN1A and SCN2A are associated with a wide spectrum of epilepsy syndromes ranging from EEs to mild disorders such as febrile seizures.2–6 Recently, de novo mutations in SCN8A, encoding one of the main voltage-gated sodium channel subunits (Nav1.6) in the brain,7 have been described in patients with severe epilepsy,8–13 although a clear clinical presentation has yet to be described or investigated. Herein, we report the phenotype of 17 patients with EE and disease-causing mutations in SCN8A.

METHODS

Patients.

SCN8A patients were identified from a large cohort of 683 patients with EEs from Denmark, Australia, North and South America, and Europe. A detailed epilepsy, developmental, and general medical history was obtained for each patient together with examination findings. EEG and imaging data were reviewed. Seizures were diagnosed according to the International League Against Epilepsy Organization, and epilepsy syndromes were established where possible.1

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents.

The study was approved by the ethics committee of Western Zealand and Austin Health and the institutional review board of the University of Washington. The parent or legal guardian of each patient gave informed consent.

Mutation analysis.

Genomic DNA was extracted using standard methods. Mutations in 7 cases were identified using targeted capture of all exons and at least 5 base pairs of flanking intronic sequence of SCN8A with molecular inversion probes (RefSeq, hg19 build, transcript ID ENST00000354534).14 Data analysis, variant calling and filtering, as well as depth of coverage statistics were generated as previously described.10 Variants were assumed to be pathogenic if they were nonsynonymous, splice-site altering, or frameshift changes, not present in 6,500 control samples (Exome Variant Server—see URLs/resources), and had arisen de novo in the patient (or was inherited from a parent with somatic mosaicism). The remaining 10 SCN8A mutations were identified by clinical or research testing at 6 centers. Traditional Sanger sequencing was used to confirm all mutations and to perform segregation analysis in parental DNA. Where possible, parental status was confirmed by microsatellite analysis.

RESULTS

Mutation analysis.

We identified 16 patients with de novo pathogenic heterozygous mutations of SCN8A and one pathogenic SCN8A mutation inherited from an unaffected somatic mosaic parent as described previously.10 Seven cases were identified using high-throughput capture and resequencing in a cohort of 683 probands with a range of EEs, accounting for approximately 1% (7/683) of cases. We obtained additional phenotypic information for one case who was previously published10 and for 10 additional patients who were referred with a de novo SCN8A mutation (table 1). None of these mutations have been identified previously in 6,500 control individuals.

Table 1.

Pathogenic SCN8A mutations in 17 patients

The 17 pathogenic mutations were distributed throughout the entire SCN8A gene (figure 1). Sixteen of 17 were missense and altered evolutionarily conserved amino acids. Notably, 4 patients (D, G, K, Q) had mutations altering the same amino acid. We identified a single individual with a 3 base pair deletion that abolished the donor splice site (predicted by MutationTaster15—see URLs/resources). Although we were unable to test the effects of this deletion on splicing, in silico analysis predicts that the disruption of this donor splice site will result in skipping of exon 24 during pre-mRNA splicing. Skipping of this 138 base pair exon would lead to an in-frame deletion of 46 amino acids from the third transmembrane domain and the intracellular loop to transmembrane domain 4.

Figure 1. De novo SCN8A mutations in patients with epileptic encephalopathy reported in this study (red dots) and in the literature (green triangles)8,9,12,13,16,23.

The letters associated with each dot correspond to the patient identification in the tables. Mutations are observed in the cytoplasmic loops, extracellular loops, and transmembrane helices. There are 3 amino acid residues that are found to be recurrently mutated: 5 occurrences at Arg1872, 3 of Arg1617Gln, and 2 of Ala1650Thr have been reported.

Clinical features of SCN8A encephalopathy.

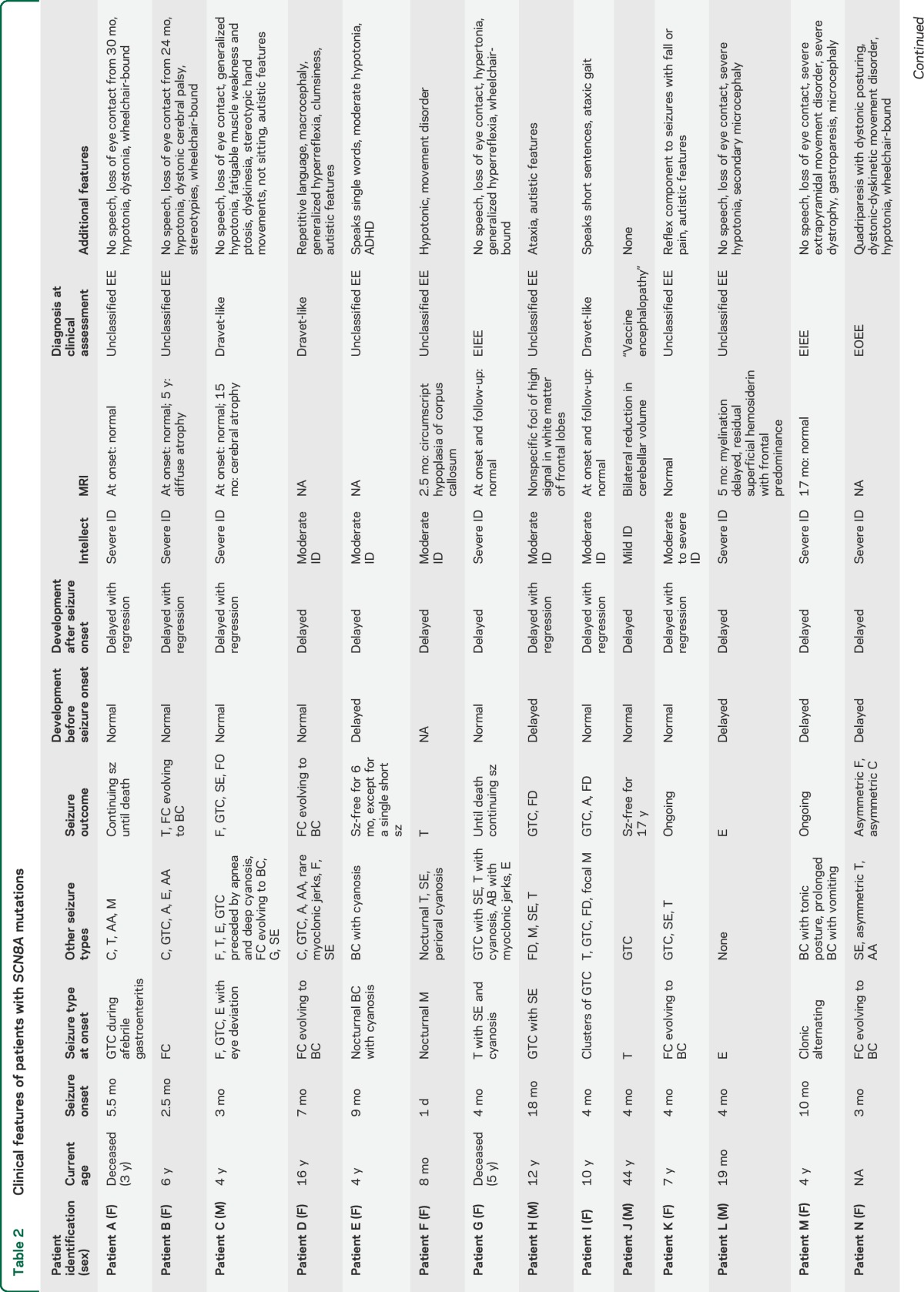

The 17 patients ranged in age from 8 months to 44 years (mean 8 years) at diagnosis; 12 were female. Seizure onset occurred at a mean of 5 months (median 4 months, range 1 day to 18 months) (table 2). Seizure semiology at onset was variable and included focal clonic seizures evolving to a bilateral convulsive seizure (7), afebrile tonic-clonic seizures (3), tonic seizures (3), epileptic spasms (2), febrile seizures (1), and myoclonic seizures (1). Fifteen of 17 patients developed additional seizure types, including generalized tonic-clonic seizures (11), epileptic spasms (5), atypical absence seizures (5), myoclonic seizures (4), and atonic seizures (1). Eight of 17 patients had episodes of convulsive (7) or nonconvulsive (1) status epilepticus.

Table 2.

Clinical features of patients with SCN8A mutations

All patients had refractory epilepsy, although 4 patients had extended seizure-free periods. Patient E was seizure-free for 6 months on valproic acid and oxcarbazepine; patient J for 17 years on carbamazepine; patient K for 8 months on valproic acid + phenytoin; patient P is currently responding to oxcarbazepine (6 weeks seizure-free); and patient O remains seizure-free after 3 years on no treatment.

The developmental pattern varied from normal development with slowing or regression after seizure onset in 12 patients, to one of abnormal development from birth in 5 with regression in one. All patients older than 18 months (n = 15) had intellectual disability that ranged from mild (1) to moderate (4) to severe (10). Of the 15 patients older than 18 months, 7 could sit and walk unassisted.

Neurologic features were prominent in the majority of cases and included hypotonia (8), dystonia (4), hyperreflexia (2), choreoathetosis (2), and ataxia (1). Psychiatric features were observed in 4 of 17 patients: 3 had autistic features and one had attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Seven of 17 patients gradually lost eye contact during the course of the disease; only one of these had autistic features.

Early death occurred in childhood in 2 patients: patient A died at 3 years during a seizure and patient G had sudden unexplained death in epilepsy (SUDEP) at 5 years.

MRI studies.

Brain MRI at onset was normal (9), abnormal (4), or not available (4). The abnormal findings included cerebral atrophy (3) and hypoplasia of the corpus callosum (1). Patients B and C had normal MRI at seizure onset with follow-up studies at ages 5 years and 15 months, respectively, showing diffuse atrophy.

EEG findings.

EEG at onset was available for 14 of 17 patients and showed focal or multifocal epileptiform activity in 6 patients and was normal in 8 (table 3). Fifteen patients developed an abnormal EEG showing moderate to severe background slowing (12) and focal or multifocal sharp waves or spikes (12), most often observed in the temporal region (8). Patients A, B, C, D, and G showed almost continuous delta slowing in the temporo-parietal-occipital regions, with superimposed beta frequencies in some and bilateral asynchronous spikes or sharp waves (figure 2).

Table 3.

EEG features of patients with SCN8A mutations

Figure 2. Interictal EEG features of patients B, D, and G.

EEG discharges in the temporo-parieto-occipital regions consist of bilateral independent spikes and sharp waves, and intermittent biposterior quadrant delta activity. EEG parameters are as follows: speed: 20 mm/s; sensitivity: 300 µV/mm; bandpass filter: 1,600–70 Hz; notch off. Pat = patient.

DISCUSSION

Our results confirm the importance of SCN8A as a cause of EEs with 7 of 683 (1%) previously unexplained cases having a causative mutation. Mutations frequently arise de novo, but we show that inherited mutations from a mosaic parent can also occur. We describe the phenotype of 17 cases with SCN8A encephalopathy bringing the total number of patients with EE due to SCN8A mutations to 30.8–13,16

Combining our series with previously published cases, seizures began in infancy at a mean age of 5 months, typically with focal seizures. Tonic-clonic seizures were seen in the majority of cases (18/30). Epileptic spasms were reported in one-third of cases either at presentation or as the disease evolved.8,11 Myoclonic and absence seizures occurred in approximately 30% of patients. Seizures were usually refractory. Notably sodium channel blockers appeared effective and allowed 4 of our patients a period of seizure freedom.

Development was normal before seizure onset in 13 of 23 cases (57%) with subsequent developmental slowing often with regression. In the remaining patients, development was not normal and regression sometimes occurred with seizure onset. In an additional 8 cases, development before seizures was not fully documented.13 Half of the patients had severe intellectual disability, and autistic features were noted in some cases (table 2). Hypotonia was often observed as well as movement disorders in some individuals manifesting as dystonia and choreoathetosis. Three patients exhibited atrophy on brain MRI, a finding that has been described in at least 2 previously reported patients.13 The atrophy is more likely to be due to the underlying sodium channelopathy, but we cannot exclude that it is secondary to treatment of the seizure disorder.

A key differential diagnosis of SCN8A encephalopathy is Dravet syndrome, which is due to SCN1A mutations in >80% of cases.17 Indeed, several of our patients were referred for genetic testing with a diagnosis of Dravet syndrome. While SCN8A encephalopathy shares some features with Dravet syndrome, there are notable differences. The mean age at onset of 5 months is similar to Dravet syndrome; however, the range of 0 days to 18 months in SCN8A encephalopathy is broader than that seen in Dravet syndrome. In contrast to the pronounced susceptibility to seizures with fever in Dravet syndrome, only 2 of 17 patients with SCN8A encephalopathy had seizures with fever. Seizure types also differ. Seven of 17 patients with SCN8A encephalopathy had spasms, which are not a feature of Dravet syndrome. Myoclonic seizures, which are common in Dravet syndrome, only occurred in 5 patients. Hypotonia and movement disorders are not features of Dravet syndrome. The EEG findings also differ in that generalized spike wave was not seen in SCN8A encephalopathy and is a hallmark of Dravet syndrome after 1 to 2 years of age. We also observed that the sodium channel blockers carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, and phenytoin rendered a few of our SCN8A cases seizure-free but are reported to exacerbate seizures in Dravet syndrome.18,19 Two of the patients in our study died aged 3 and 5 years, one of SUDEP, which has been reported in one other patient with an SCN8A mutation.8 Larger series of patients with mutations in SCN8A will be required to determine the overall risk of SUDEP in this patient population.

The mutations reported in this study were distributed throughout the protein (figure 1). None were located in the known protein–protein interaction regions of SCN8A.20 In 4 patients, we observed mutations altering the same amino acid (1872, transcript ID ENST00000354534); alteration of this residue was previously reported in a patient with EE.13 There are 2 additional recurrent mutations: the Arg1617Gln reported here has been seen in 2 additional patients with severe intellectual disability and epilepsy (3 mutations total) and the Ala1650Thr in one additional patient (2 mutations total).9,13 These findings reveal amino acid position 1872 as a mutation hotspot and positions 1617 and 1650 as likely emerging hotspots. It will be important for future studies to establish the effect of these pathogenic mutations on SCN8A function. It is likely that pathogenic SCN8A missense mutations act in a gain-of-function manner, similar to the de novo Asn1768Asp and Thr176Ile mutations identified in patients with EE.8,16 In vitro studies of the Asn1768Asp demonstrated that the mutant channel had incomplete channel activation, increase in persistent sodium current, and a depolarizing shift in voltage dependence of steady-state fast inactivation.8 Similar studies for the Thr767Ile mutation demonstrated analogous biophysical properties of the mutant channel.16 Collectively, these results suggest that the mutant channels lead to increased excitability of the neuron, and that this feature is likely to underlie the epilepsy in patients with de novo missense mutations.

We identified a single patient with a de novo splice-site mutation that is predicted to give rise to an in-frame deletion of 46 amino acids because of exon skipping. This deletion would remove a portion of the third transmembrane domain and the intracellular loop that serves as the inactivation gate.20 It will be important to establish whether this mutation also acts in a gain-of-function manner. Loss-of-function mutations seem to be associated with intellectual disability and ataxia in humans,20 and homozygous null mice present with ataxia and impaired learning.21,22 Future sequence-based studies in patients with these disorders, as well as functional validation of the effects of different types of SCN8A mutations, are needed to determine whether distinct mutations in SCN8A cause diverse neurologic manifestations.

It is also worth noting that despite the identification of 30 patients with de novo SCN8A mutations throughout the protein, there does not appear to be any genotype–phenotype correlation regarding the position of the mutation and the seizure onset, types, or severity of clinical presentation. This is exemplified by the recurrent missense mutation at protein position 1872, which has now been described in 5 patients, 4 here and one previously.13 Even though these individuals have the same primary genetic lesion, clinical presentation was variable. Onset of seizures ranged from 1 to 7 months; 3 patients first presented with tonic or tonic-clonic seizures, and 2 with focal clonic seizures that evolved to bilateral convulsive seizures. Multiple seizure types were subsequently present in all cases, and intellectual disability ranged from moderate to severe. The only feature common to all patients was normal development before seizure onset. A greater number of patients with SCN8A mutations will need to be identified in the future to determine whether there are any phenotypic or genotypic subgroups that may be delineated.

SCN8A mutations are found in 1% of patients with previously unexplained infantile-onset EE. We present the largest series of patients with pathogenic SCN8A mutations to date. We observed a wide spectrum of phenotypes of the EEs in all patients; seizure onset, type, and neurodevelopment and progression were all variable within our cohort. An emerging phenotype seems to consist of seizure onset by 18 months with multiple seizure types and developmental slowing. Whether this lack of a distinct clinical presentation is attributable to the relatively small number of patients who have been identified or reflects a true spectrum remains to be seen. Of note, despite the lack of clear phenotype, the observation that sodium channel blockers may be effective in these cases underscores the importance of a molecular diagnosis. It also argues for unbiased genetic testing as part of a gene panel or exome in children with EEs. Our study highlights the power of such an approach, whereby a genotype first paradigm can advance our understanding of the clinical presentation of patients, which may in turn guide therapeutic choices in the future, enable recognition of associated comorbidities, and inform prognostic counseling.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank the families for their participation in this study.

GLOSSARY

- EE

epileptic encephalopathy

- SCN8A

sodium channel, voltage-gated, type VIII, α subunit

- SUDEP

sudden unexplained death in epilepsy

Footnotes

Editorial, page 446

Contributor Information

Collaborators: Aarno Palotie, Anna-Elina Lehesjoki, Arvid Suls, Bobby Koeleman, Carla Marini, Christel Depienne, Dana Craiu, Deb Pal, Dorota Hoffman-Zacharska, Eric Leguern, Federico Zara, Felix Rosenow, Hande Caglayan, Helle Hjalgrim, Hiltrud Muhle, Holger Lerche, Ingo Helbig, Johanna Jähn, Johannes Lemke, Jose M Serratosa, Kaja Selmer, Karl Martin Klein, Katalin Sterbova, Nina Barisic, Padhraig Gormley, Pasquale Striano, Patrick May, Peter De Jonghe, Renzo Guerrini, Rikke S. Møller, Roland Krause, Rudi Balling, Sanjay Sisodiya, Sarah von Spiczak, Sarah Weckhuysen, Stéphanie Baulac, Tiina Talvik, Ulrich Stephani, Vladimir Komarek, and Yvonne Weber

URLs/RESOURCES

PolyPhen-2: http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/; SIFT: http://sift.jcvi.org/; Exome Variant Server: http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/; MutationTaster: http://www.mutationtaster.org/; GATK: http://www.broadinstitute.org/gatk/.

AUTHOR AFFILIATIONS

From the Danish Epilepsy Centre (J.L., E.G., B.J., H.H., R.S.M.); ICMM (J.L., Y.M., N.T.), Panum Institute, University of Copenhagen, Denmark; Department of Pediatrics (G.L.C., H.C.M.), Division of Genetic Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle; Clinic for Neuropediatrics and Neurorehabilitation (G.K.), Epilepsy Center for Children and Adolescents, Schön Klinik Vogtareuth, Germany; Departments of Medical Genetics and Child Neurology (E.B., B.K., K.B.), University Medical Center Utrecht, the Netherlands; Clinic for Children and Adolescents (G.S.), Esslingen, Germany; Université Pierre et Marie Curie (C.D.), Faculté de Médecine, Paris; INSERM UMRS 975 (C.D.), CNRS UMR 725, Paris, France; Institüt für Humangenetik (C.D.), Universität Würzburg, Germany; Department of Clinical Medicine (J.E.K.N.), Section of Gynaecology, Obstetrics and Paediatrics, Roskilde Hospital; UMC Utrecht (C.G.F.d.K.), Medical Genetics Research; Child Neurology Service Hospital San Borja Arriarán (M.T., L.T.), University of Chile, Santiago; Florey Institute Melbourne (I.E.S.); Epilepsy Research Centre (J.M.M., I.E.S.), Department of Medicine, University of Melbourne, Austin Health; Department of Paediatrics (I.E.S.), Royal Children's Hospital, University of Melbourne, Australia; Department of Pediatric Neurology (A.B., M.W.), University Children's Hospital, Tübingen, Germany; Institute of Regional Health Services Research (J.L., E.G., H.H., R.S.M.), Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Southern Denmark; Department of Pediatrics (N.B.), University Hospital Centre Zagreb; Neurogenetics Group (T.D., S.W.), Department of Molecular Genetics, VIB, Antwerp; Laboratory of Neurogenetics (T.D., S.W.), Institute Born-Bunge, University of Antwerp, Belgium; Child Neurology Unit (N.S., R. Guerrini), Children's Hospital A. Meyer and University of Florence; Child Neurology Unit (C.M.), Pediatric Hospital Bambino Gesú, Rome, Italy; Tayside Children's Hospital (M.K., R. Goldman), Dundee; Ninewells Hospital and Medical School (D. Goudie), Dundee, UK, for the DDD Study; CeGaT GmbH–Center for Genomics and Transcriptomics (M.D., S.B.), Tübingen; University Medical Center Schleswig-Holstein (J.A.J.), Christian-Albrechts University, Kiel, Germany; T.Y. Nelson Department of Neurology (D. Gill), The Children's Hospital at Westmead, Sydney, Australia; and Department of Neurology (M.H.), Division of Child Neurology, Riley Hospital for Children, Indiana University Health.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Jan Larsen: drafting/revising the manuscript, study concept or design, analysis or interpretation of data, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, acquisition of data, statistical analysis, study supervision. Gemma Louise Carvill: drafting/revising the manuscript, study concept or design, analysis or interpretation of data, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval. Elena Gardella: drafting/revising the manuscript, study concept or design, analysis or interpretation of data, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval. Gerhard Kluger: drafting/revising the manuscript, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, acquisition of data. Gudrun Schmiedel: drafting/revising the manuscript, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, acquisition of data. Nina Barisic: analysis or interpretation of data, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, acquisition of data, study supervision. Christel Depienne: drafting/revising the manuscript, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, contribution of vital reagents/tools/patients. Eva Brilstra: analysis or interpretation of data, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, acquisition of data. Yuan Mang: analysis or interpretation of data, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval. Jens Erik Klint Nielsen: drafting/revising the manuscript, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval. Martin Kirkpatrick: drafting/revising the manuscript, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval. David Goudie: analysis or interpretation of data, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, acquisition of data. Rebecca Goldman: drafting/revising the manuscript, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, acquisition of data. Johanna A. Jähn: drafting/revising the manuscript, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, study supervision. Birgit Jepsen: drafting/revising the manuscript, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval. Deepak Gill: drafting/revising the manuscript, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval. Miriam Döcker: analysis or interpretation of data, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval. Saskia Biskup: analysis or interpretation of data, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, acquisition of data. Jacinta M. McMahon: drafting/revising the manuscript, analysis or interpretation of data, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, acquisition of data. Bobby Koeleman: drafting/revising the manuscript, study concept or design, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, acquisition of data. Mandy O. Harris: analysis or interpretation of data, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval. Kees Braun: analysis or interpretation of data, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, acquisition of data. Carolien de Kovel: analysis or interpretation of data, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, acquisition of data. Carla Marini: drafting/revising the manuscript, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, acquisition of data. Nicola Specchio: drafting/revising the manuscript, analysis or interpretation of data, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, acquisition of data. Tania Djémié: drafting/revising the manuscript, analysis or interpretation of data, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, acquisition of data. Sarah Weckhuysen: drafting/revising the manuscript, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, contribution of vital reagents/tools/patients, acquisition of data. Niels Tommerup: study concept or design, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, contribution of vital reagents/tools/patients. Monica Troncoso: drafting/revising the manuscript, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, contribution of vital reagents/tools/patients. Ledia Troncoso: drafting/revising the manuscript, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, contribution of vital reagents/tools/patients. Andrea Bevot: drafting/revising the manuscript, analysis or interpretation of data, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, acquisition of data. Markus Wolff: drafting/revising the manuscript, analysis or interpretation of data, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, acquisition of data. Helle Hjalgrim: drafting/revising the manuscript, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, acquisition of data, study supervision. Renzo Guerrini: drafting/revising the manuscript, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, acquisition of data. Ingrid E. Scheffer: drafting/revising the manuscript, study concept or design, analysis or interpretation of data, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, acquisition of data, study supervision, obtaining funding. Heather C. Mefford: drafting/revising the manuscript, study concept or design, analysis or interpretation of data, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, contribution of vital reagents/tools/patients, acquisition of data, study supervision, obtaining funding. Rikke S. Møller: drafting/revising the manuscript, study concept or design, analysis or interpretation of data, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, study supervision.

STUDY FUNDING

The research is supported by Wilhelm Johannsen Centre for Functional Genome Research, ICMM, University of Copenhagen, NIH (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke 1R01NS069605) to H.C.M., the American Epilepsy Society and the Lennox and Lombroso Fund to G.L.C., National Health and Medical Research Foundation to S.F.B. and I.E.S., the Lundbeck Foundation (2012–6206) to N.T., Institüt für Humangenetik, Universität Würzburg, Patient P was part of the DDD Study, which presents independent research commissioned by the Health Innovation Challenge Fund (grant HICF-1009-003), a parallel funding partnership between the Wellcome Trust and the Department of Health, and the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute (grant WT098051). The research team acknowledges the support of the National Institute for Health, funds from the Italian Minister of Health, RF 2009-1525669; special thanks to Eurocores program EuroEPINOMICS of the European Science Foundation (P.D.J.).

DISCLOSURE

J. Larsen, G. Carvill, E. Gardella, G. Kluger, G. Schmiedel, N. Barisic, C. Depienne, E. Brilstra, Y. Mang, J. Nielsen, M. Kirkpatrick, D. Goudie, R. Goldman, J. Jähn, B. Jepsen, D. Gill, M. Döcker, S. Biskup, J. McMahon, B. Koeleman, M. Harris, K. Braun, C. de Kovel, C. Marini, N. Specchio, T. Djémié, S. Weckhuysen, N. Tommerup, M. Troncoso, L. Troncoso, A. Bevot, M. Wolff, H. Hjalgrim, and R. Guerrini report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. I. Scheffer has served on scientific advisory boards for UCB and Janssen-Cilag EMEA; serves on the editorial boards of the Annals of Neurology, Neurology®, and Epileptic Disorders; may accrue future revenue on pending patent WO61/010176 (filed 2008): Therapeutic Compound; has received speaker honoraria from GlaxoSmithKline, Athena Diagnostics, UCB, Biocodex, and Janssen-Cilag EMEA; has received funding for travel from Athena Diagnostics, UCB, Biocodex, GlaxoSmithKline, and Janssen-Cilag EMEA; and receives/has received research support from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, NIH, Australian Research Council, Health Research Council of New Zealand, CURE, American Epilepsy Society, US Department of Defense Autism Spectrum Disorder Research Program, the Jack Brockhoff Foundation, the Shepherd Foundation, Perpetual Charitable Trustees, and The University of Melbourne. H. Mefford has received a grant from the NIH/National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, Burroughs Wellcome Fund, and is a consultant for the Simons Foundation (SFARI Gene Advisory Board). R. Møller reports no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Go to Neurology.org for full disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Berg AT, Berkovic SF, Brodie MJ, et al. Revised terminology and concepts for organization of seizures and epilepsies: report of the ILAE Commission on Classification and Terminology, 2005–2009. Epilepsia 2010;51:676–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heron SE, Crossland KM, Andermann E, et al. Sodium-channel defects in benign familial neonatal-infantile seizures. Lancet 2002;360:851–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Escayg A, MacDonald BT, Meisler MH, et al. Mutations of SCN1A, encoding a neuronal sodium channel, in two families with GEFS+2. Nat Genet 2000;24:343–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Claes L, Del-Favero J, Ceulemans B, Lagae L, Van Broeckhoven C, De Jonghe P. De novo mutations in the sodium-channel gene SCN1A cause severe myoclonic epilepsy of infancy. Am J Hum Genet 2001;68:1327–1332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Herlenius E, Heron SE, Grinton BE, et al. SCN2A mutations and benign familial neonatal-infantile seizures: the phenotypic spectrum. Epilepsia 2007;48:1138–1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oliva M, Berkovic SF, Petrou S. Sodium channels and the neurobiology of epilepsy. Epilepsia 2012;53:1849–1859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lorincz A, Nusser Z. Molecular identity of dendritic voltage-gated sodium channels. Science 2010;328:906–909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Veeramah KR, O'Brien JE, Meisler MH, et al. De novo pathogenic SCN8A mutation identified by whole-genome sequencing of a family quartet affected by infantile epileptic encephalopathy and SUDEP. Am J Hum Genet 2012;90:502–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rauch A, Wieczorek D, Graf E, et al. Range of genetic mutations associated with severe non-syndromic sporadic intellectual disability: an exome sequencing study. Lancet 2012;380:1674–1682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carvill GL, Heavin SB, Yendle SC, et al. Targeted resequencing in epileptic encephalopathies identifies de novo mutations in CHD2 and SYNGAP1. Nat Genet 2013;45:825–830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Epi4K Consortium, Epilepsy Phenome/Genome Project; Allen AS, Berkovic S, Cossette P, et al. De novo mutations in epileptic encephalopathies. Nature 2013;501:217–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vaher U, Noukas M, Nikopensius T, et al. De novo SCN8A mutation identified by whole-exome sequencing in a boy with neonatal epileptic encephalopathy, multiple congenital anomalies, and movement disorders. J Child Neurol 2013;29:NP202–NP206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ohba C, Kato M, Takahashi S, et al. Early onset epileptic encephalopathy caused by de novo SCN8A mutations. Epilepsia 2014;55:994–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O'Roak BJ, Vives L, Fu W, et al. Multiplex targeted sequencing identifies recurrently mutated genes in autism spectrum disorders. Science 2012;338:1619–1622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schwarz JM, Rodelsperger C, Schuelke M, Seelow D. MutationTaster evaluates disease-causing potential of sequence alterations. Nat Methods 2010;7:575–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Estacion M, O'Brien JE, Conravey A, et al. A novel de novo mutation of SCN8A (Na1.6) with enhanced channel activation in a child with epileptic encephalopathy. Neurobiol Dis 2014;69:117–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Helbig I, Lowenstein DH. Genetics of the epilepsies: where are we and where are we going? Curr Opin Neurol 2013;26:179–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chiron C. Current therapeutic procedures in Dravet syndrome. Dev Med Child Neurol 2011;53(suppl 2):16–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arzimanoglou A. Dravet syndrome: from electroclinical characteristics to molecular biology. Epilepsia 2009;50(suppl 8):3–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O'Brien JE, Meisler MH. Sodium channel (Na1.6): properties and mutations in epileptic encephalopathy and intellectual disability. Front Genet 2013;4:213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Woodruff-Pak DS, Green JT, Levin SI, Meisler MH. Inactivation of sodium channel Scn8A (Na-sub(v)1.6) in Purkinje neurons impairs learning in Morris water maze and delay but not trace eyeblink classical conditioning. Behav Neurosci 2006;120:229–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burgess DL, Kohrman DC, Galt J, et al. Mutation of a new sodium channel gene, Scn8a, in the mouse mutant “motor endplate disease”. Nat Genet 1995;10:461–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Allen AS, Berkovic SF, Cossette P, et al. De novo mutations in epileptic encephalopathies. Nature 2013;501:217–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.