Abstract

Objective:

To determine the predictive utility of baseline odor identification deficits for future cognitive decline and the diagnosis of Alzheimer disease (AD) dementia.

Methods:

In a multiethnic community cohort in North Manhattan, NY, 1,037 participants without dementia were evaluated with the 40-item University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test (UPSIT). In 757 participants, follow-up occurred at 2 years and 4 years.

Results:

In logistic regression analyses, lower baseline UPSIT scores were associated with cognitive decline (relative risk 1.067 per point interval; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.040, 1.095; p < 0.0001), and remained significant (relative risk 1.065 per point interval; 95% CI 1.034, 1.095; p < 0.0001) after including covariates. UPSIT, but not Selective Reminding Test–total immediate recall, predicted cognitive decline in participants without baseline cognitive impairment. During follow-up, 101 participants transitioned to AD dementia. In discrete time survival analyses, lower baseline UPSIT scores were associated with transition to AD dementia (hazard ratio 1.099 per point interval; 95% CI 1.067, 1.131; p < 0.0001), and remained highly significant (hazard ratio 1.072 per point interval; 95% CI 1.036, 1.109; p < 0.0001) after including demographic, cognitive, and functional covariates.

Conclusions:

Impairment in odor identification was superior to deficits in verbal episodic memory in predicting cognitive decline in cognitively intact participants. The findings support the cross-cultural use of a relatively inexpensive odor identification test as an early biomarker of cognitive decline and AD dementia. Such testing may have the potential to select/stratify patients in treatment trials of cognitively impaired patients or prevention trials in cognitively intact individuals.

Neurofibrillary tangles in the olfactory bulb are an early pathologic sign of Alzheimer disease (AD). Odor identification deficits during life are associated with tangles in the olfactory bulb and central olfactory projection areas at autopsy.1,2 Odor identification deficits distinguish patients with AD dementia from controls,3,4 and these deficits are greater in mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and mild AD dementia compared with cognitively intact controls even after accounting for odor detection and odor discrimination abilities.5

Odor identification deficits predict the transition from MCI to AD dementia.4 In a 3-year follow-up study, these deficits were associated with 4 to 5 times increased likelihood of transitioning from MCI to AD dementia.6 Epidemiologic studies show similar, although smaller, effects.7 In older adults without significant cognitive impairment, odor identification deficits increase the likelihood of transitioning to MCI,8 but their utility in predicting cognitive decline more broadly remains unclear.

In a multiethnic elderly community study, University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test (UPSIT) scores were similar between English and Spanish test administrations after controlling for age, sex, and education.9 Participants without MCI had higher UPSIT scores than participants with nonamnestic MCI, who had higher UPSIT scores than participants with amnestic MCI.

We now report on follow-up data in this cohort. We hypothesized that baseline odor identification deficits would predict cognitive decline and be superior to episodic verbal memory deficits in this prediction. We also hypothesized that odor identification deficits would significantly predict the transition from MCI to AD dementia even after controlling for demographic, clinical, and cognitive measures.

METHODS

Participants.

A stratified random sample of 50% of all Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 years and older, obtained from the Health Care Finance Administration, was recruited initially from a specific region of North Manhattan, NY.10 This Washington Heights/Inwood Columbia Aging Project (WHICAP) cohort includes participants recruited originally in 1992 (approximately 25% of subjects) and a new cohort recruited between 1999 and 2001 (approximately 75% of subjects).11 At each visit, all participants received a standardized neuropsychological test battery that included measures of learning and memory, orientation, abstract reasoning, executive function, language, and visuospatial ability. The sum of 6 items for instrumental activities of daily living formed a function score.11 A standardized neurologic examination included a 10-item version of the Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale12 that was used to diagnose Parkinson disease based on research criteria.13

Olfactory testing.

Odor identification testing was performed with the UPSIT, a highly reliable, sensitive, and well-validated olfactory test.14–16 The research technician administered the English or Spanish version of the UPSIT depending on the participant's language preference. The neuropsychological tests and the UPSIT were administered in the same language. In the UPSIT, each of 40 common odorants is embedded in microcapsules located on separate pages of 10-page booklets. The participant scratches an odorant strip containing the microencapsulated odorant page, sniffs the emanated odor, and chooses the best answer from 4 items listed as multiple choice. The total score ranges from 0 (no odors correctly identified) to 40 (all odors correctly identified). For study inclusion, the participant needed to complete a minimum 38 of 40 UPSIT items. For participants who completed 38 or 39 items, a score of 0.25 was imputed for each missing item.8

The study sample comprised participants without dementia who received the UPSIT and met specific inclusion/exclusion criteria.11,17 Clinical stroke and Parkinson disease were excluded.11 The UPSIT was first administered at the evaluation between 2004 and 2006, identified as “baseline” for this report. Follow-ups occurred during 2006–2008 (first follow-up) and 2008–2010 (second follow-up). At all time points, consensus diagnoses of dementia, including AD dementia, were made as described previously, based on available clinical, cognitive, and functional information but without UPSIT data. Cognitive decline was defined a priori as a decline in the average of the 3 cognitive composite scores of 1 SD or greater for 4-year follow-up or a decline of 0.5 SD or greater if follow-up was limited to 2 years. Outcomes at the last available follow-up time point were used.

MCI classification and cognitive composite scores.

Based on a previously published factor analytic approach within this cohort, composite cognitive domain scores were derived for memory, language, and visual-spatial ability.18 The memory composite comprised three 12-item 6-trial Selective Reminding Test (SRT) measures (total immediate recall or SRT-TR, delayed recall, and delayed recognition); the language composite comprised measures of naming, letter and category fluency, verbal abstract reasoning, repetition, and comprehension; and the visual-spatial ability composite comprised the Benton Visual Retention Test recognition and matching variables, the Rosen Drawing Test, and the Identities and Oddities subtest. The classification of amnestic MCI required memory complaints, intact function, and a score of 1.5 SD below standardized norms on a composite of verbal and nonverbal memory measures with or without other cognitive domain deficits. Nonamnestic MCI required a similar level of deficit in any nonmemory cognitive domain composite.18 In this epidemiologic study, norms adjusted for language of administration and other demographics have been described elsewhere.11

MRI protocol.

Scan acquisition was performed on a 1.5T Philips Intera scanner (Philips Medical Systems, Best, the Netherlands) at Columbia University Medical Center and transferred electronically to the University of California at Davis for morphometric analysis. As described previously,9,19 fluid-attenuated inversion recovery weighted axial images were used to assess white matter hyperintensities, and T1-weighted images acquired in the axial plane and resectioned coronally were used to quantify hippocampus and entorhinal cortex volumes. The sum of right and left hippocampal and entorhinal cortex volumes were used in analyses.

APOE genotyping.

DNA was amplified by PCR and genotypes were assessed by sizes of DNA fragments. APOE genotypes were determined blinded to participant status.

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents.

The Columbia University–New York State Psychiatric Institute institutional review board approved the study protocol and informed consent forms.

Statistical analyses.

Distributions and group differences in demographic and clinical variables were examined by χ2, t test, and general linear models. Spearman correlations between UPSIT scores and demographic, cognitive, functional, and MRI measures were evaluated. The definition of cognitive decline was based on the trend (change) in the composite cognitive domain scores during follow-up instead of being measured directly as the outcome at each visit. Therefore, logistic regression analyses were used for the outcome of cognitive decline. Discrete time survival models were used to evaluate the associations between baseline UPSIT scores and the outcome of AD dementia. Covariates were age, sex, education, SRT-TR (cognitive measure selected a priori), and functional impairment. In receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analyses, area under the curve (AUC, trapezoidal rule) was compared across different models using the bootstrapping method.20 The Youden Index was used to determine optimal cutoff values.21 Analyses were conducted in SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and R (v.3.0.1) package pROC.

RESULTS

Baseline demographic and clinical measures.

At initial evaluation, 1,037 of 1,119 participants (92.7%) without dementia met inclusion/exclusion criteria for this report. The UPSIT was higher in participants without MCI compared with nonamnestic MCI, and higher in nonamnestic MCI compared with amnestic MCI in the total sample (n = 1,037) and follow-up sample (n = 757, table 1). Spanish and English UPSIT scores did not differ after adjusting for age and years of education for both the total sample (p = 0.1874) and the follow-up sample (p = 0.9513).

Table 1.

Demographics and clinical measures at the initial evaluation

Baseline correlations.

UPSIT scores correlated significantly with age (r = −0.26, p < 0.0001), education (r = 0.19, p < 0.0001), SRT-TR (r = 0.32, p < 0.0001), SRT–delayed recall (r = 0.28, p < 0.0001), letter fluency (r = 0.28, p < 0.0001), category fluency (r = 0.31, p < 0.0001), naming (r = 0.22, p < 0.0001), Color Trails time (r = −0.26, p < 0.0001), and hippocampal volume (r = 0.15, p = 0.0004) in the 544 participants who had MRI scans. The UPSIT score did not correlate significantly with smoking (current or past smoker), Center for Epidemiological Studies–Depression scores, entorhinal cortex volume, or white matter hyperintensity volume, and was not related to APOE ε4 allele status.

Follow-up.

In 757 participants who completed at least one follow-up, 109 transitioned to dementia, among whom 101 transitioned to AD dementia. Two participants transitioned to vascular dementia, 3 participants to Lewy body dementia, and 3 participants to other causes of dementia. For participants with baseline status of no MCI, nonamnestic MCI, and amnestic MCI, transition rates to dementia at final follow-up were 35/498 (7.03%), 32/129 (24.81%), and 42/130 (32.31%), respectively (χ2 = 67.11, p < 0.0001). Similar results were obtained for the outcome of AD dementia at follow-up: no MCI 6.64%, nonamnestic MCI 24.03%, and amnestic MCI 28.46% (χ2 = 57.69, p < 0.0001). In the 544 participants who had MRI scans, 405 were followed. In this subsample, mean hippocampal volume did not differ significantly (p = 0.255) among participants with no MCI (mean 3.38 cm3, SD 0.67), nonamnestic MCI (mean 3.27 cm3, SD 0.75), and amnestic MCI (mean 3.24 cm3, SD 0.70).

Prediction of cognitive decline.

In the follow-up sample (n = 757), participants with cognitive decline (n = 151) had a mean baseline UPSIT score of 24.28 (SD 6.35) compared to that of 27.33 (SD 6.70) in nondecliners (n = 581), with participants not followed (n = 25) having the lowest UPSIT scores (mean 21.24, SD 7.64). In logistic regression analyses, lower baseline UPSIT scores were strongly associated with subsequent cognitive decline (relative risk [RR] 1.067 per point interval; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.040, 1.095; p < 0.0001). Lower baseline UPSIT scores remained significant (RR 1.065 per point interval; 95% CI 1.034, 1.095; p < 0.0001) after including covariates in the model (table 2).

Table 2.

Logistic regression analyses: Cognitive decline in the total sample with available follow-up composite scores (n = 732) and in participants cognitively intact (without MCI) at baseline (n = 498)

In participants without MCI at baseline (n = 498), those who showed cognitive decline (n = 102) had a mean baseline UPSIT score of 24.58 (SD 6.30) compared with a mean baseline UPSIT score of 28.54 (SD 6.20) in nondecliners (n = 387). Participants not followed (n = 9) had the lowest UPSIT scores (mean 22.33, SD 7.66). In logistic regression analyses, a lower UPSIT score was strongly associated with subsequent cognitive decline (RR = 1.096 per point interval; 95% CI 1.060, 1.135; p < 0.0001). Lower baseline UPSIT remained highly significant (RR 1.089 per point interval; 95% CI 1.050, 1.130; p < 0.0001) after the inclusion of covariates in the model (table 2). When only the UPSIT and SRT-TR measures were included in the logistic regression model, the UPSIT remained significant (RR 1.094 per point interval; 95% CI 1.057, 1.133) but SRT-TR was not significant (RR 1.010 per point interval; 95% CI 0.983, 1.037; p = 0.478).

Transition to AD dementia.

In discrete time survival analyses in the follow-up sample (n = 757), lower baseline UPSIT scores were strongly associated with transition to AD dementia (hazard ratio [HR] 1.099 per point interval; 95% CI 1.067, 1.131; p < 0.0001). Lower baseline UPSIT scores remained highly significant (HR 1.072 per point interval; 95% CI 1.036, 1.109; p < 0.0001) after the inclusion of sex, age, test language, education, SRT-TR, and functional impairment as covariates in the model. Compared to the fourth quartile with the highest UPSIT scores, the HRs for transition to AD dementia for the first, second, and third quartiles of UPSIT scores were 10.33 (95% CI 4.55, 23.49), 5.68 (95% CI 2.44, 13.20), and 3.92 (95% CI 1.60, 9.58), respectively (figure 1).

Figure 1. Baseline UPSIT quartile scores in patients who transitioned to AD dementia during follow-up.

In 757 participants without dementia who were followed, percent transitioning to AD classified by baseline UPSIT quartile scores. Q1 represents the quartile with the lowest UPSIT scores (worst quartile test performance) and Q4 represents the quartile with the highest UPSIT scores (best quartile test performance) that was used as the reference group in the analyses of other quartiles. AD = Alzheimer disease; UPSIT = University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test.

In survival analyses restricted to participants with MCI at baseline (n = 259), lower baseline UPSIT scores were associated significantly with transition to AD dementia (HR 1.064 per point interval; 95% CI 1.024, 1.106; p < 0.0017). Lower baseline UPSIT scores remained highly significant (HR 1.058; 95% CI 1.015, 1.104; p = 0.008) after the inclusion of sex (p = 0.064), age (p = 0.061), test language (p = 0.701), education (p = 0.209), SRT-TR (p = 0.003), and functional impairment (p = 0.236) as variables in the survival model. Essentially identical results were obtained for the same set of analyses conducted for the outcome of transition to dementia.

APOE ε4 genotype (p = 0.07), and in the subset of participants who received MRI scans, hippocampal volume (p = 0.32), entorhinal cortex volume (p = 0.68) and white matter hyperintensity volume (p = 0.57), each adjusted for demographic and clinical covariates, were not significant individual predictors of either cognitive decline or MCI transition to AD dementia. Smoking (current or past smoker) also was not a significant covariate in the analyses of cognitive decline or AD dementia as outcomes. In all analyses, including SRT–delayed recall instead of SRT-TR led to similar results (e.g., table 2).

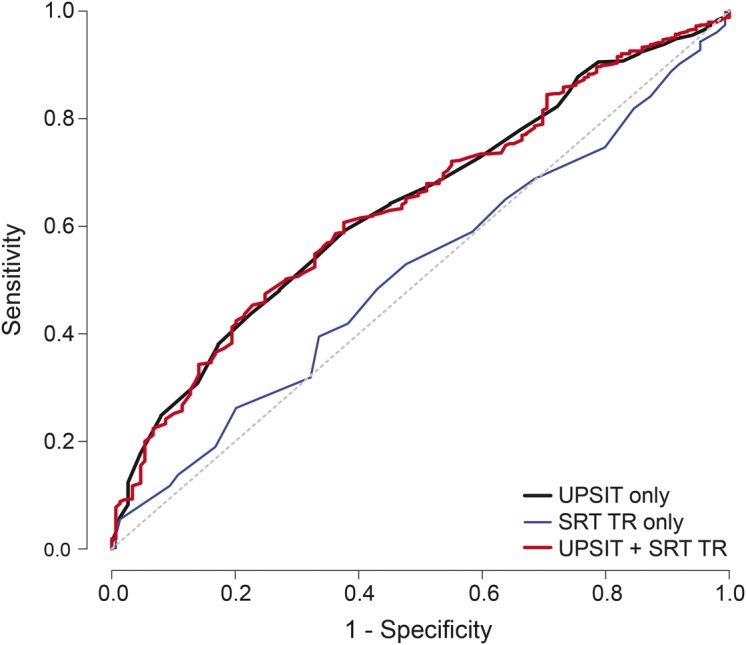

ROC analyses.

In ROC analyses, for the prediction of cognitive decline, the AUC for the UPSIT was significantly greater than for SRT-TR (0.638 vs 0.513, p < 0.001; figure 2). For cognitive decline, the AUC for the UPSIT and SRT-TR combined was not superior to the UPSIT alone (figure 2). For the transition to AD dementia, the AUC for the UPSIT and SRT-TR combined (0.77) improved prediction compared with the individual AUCs (0.65 and 0.73) as displayed in figure 3. For the UPSIT alone, for a fixed sensitivity of 50%, the specificity was 66.89% for cognitive decline and 73.13% for the transition to AD dementia.

Figure 2. Receiver operating characteristic curves for odor identification and episodic verbal memory in predicting cognitive decline.

Cognitive decline. In the entire follow-up sample, 732 of 757 participants (25 missing) provided data for cognitive decline. Receiver operating characteristic curves for cognitive decline for the 40-item UPSIT, SRT-TR, and UPSIT plus SRT-TR. AUC: UPSIT = 0.638, SD 0.024; SRT-TR = 0.513, SD 0.025; UPSIT + SRT-TR = 0.638, SD 0.024. Comparison of AUCs: UPSIT > SRT-TR (p < 0.001), (UPSIT + SRT-TR) > SRT-TR (p < 0.001). AUC = area under the curve; SRT-TR = Selective Reminding Test–total immediate recall; UPSIT = University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test.

Figure 3. Receiver operating characteristic curves for odor identification and episodic verbal memory in predicting AD dementia.

Transition to AD. In the entire follow-up sample (n = 757), receiver operating characteristic curves for transition to AD for the 40-item UPSIT, SRT-TR, and UPSIT plus SRT-TR. AUC: UPSIT = 0.65, SRT-TR = 0.73, UPSIT + SRT-TR = 0.77. Comparison of AUCs: SRT-TR > UPSIT (p = 0.02), (UPSIT + SRT-TR) > SRT-TR (p = 0.01). AD = Alzheimer disease; AUC = area under the curve; SRT-TR = Selective Reminding Test–total immediate recall; UPSIT = University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test.

DISCUSSION

The UPSIT, unlike SRT-TR, significantly predicted cognitive decline and retained significance with both measures included in the model, indicating an advantage for odor identification deficits over episodic verbal memory in predicting cognitive decline in cognitively intact individuals. Our findings with episodic verbal memory support another report showing that cognitive test performance does not predict subsequent cognitive decline in cognitively intact community-residing older adults.22

In community studies, olfactory identification deficits have been shown to be associated with decline in Mini-Mental State Examination scores23 and verbal memory.24,25 In a sample of 589 cognitively intact elderly subjects, lower scores on the Brief Smell Identification Test (a 12-item subset of the UPSIT) were associated with a 50% increased risk of developing MCI over a 5-year period.8 The Brief Smell Identification Test also predicted cognitive decline during 2 years of follow-up in a Japanese-American epidemiologic cohort. This effect was prominent in APOE ε4 carriers,7 similar to findings in smaller clinical samples.26,27 We did not observe an association between UPSIT scores and the APOE ε4 allele; other reports from the WHICAP multiethnic cohort have shown an APOE ε4 predictive effect only in participants already diagnosed with AD dementia.28

In this study, odor identification deficits predicted both cognitive decline and AD dementia in the same population-based community cohort. The UPSIT showed significant predictive utility for the outcome of AD dementia in this community sample with relatively low transition rates to AD dementia, supporting the findings in clinical samples with higher transition rates to AD dementia.4,6 Both episodic verbal memory deficits and odor identification deficits predicted AD dementia, and the combination was superior to each measure in this prediction as observed in clinical prediction studies.6

The results support the use of the UPSIT in both English- and Spanish-speaking individuals provided age, sex, and education are taken into account.9 In an Italian clinical study, the UPSIT was modified to include 34 (of 40) culturally relevant items. In that study, in 88 patients with MCI, 47% of patients with low olfactory scores (<24) progressed to dementia in 2 years compared with 11% of patients with normal olfactory scores (≥24).29 The UPSIT and similar tests, with culturally appropriate modifications when needed, can be a useful predictor of cognitive decline and the transition to AD dementia across different ethnicities.

In AD, there is disease pathology in both the olfactory bulb and higher order olfactory processing areas that are involved in olfactory function. Therefore, a variety of olfactory deficits can occur, and among them odor identification deficits can precede the clinical manifestation of cognitive impairment. Odor identification impairment as a biomarker of future cognitive decline, even if not very specific to AD, is consistent with the evidence that AD neuropathology develops decades before classic clinical manifestations.30

There were some limitations to this study. Participants who were not followed had lower UPSIT and memory test scores, indirectly suggesting that survivor bias may have rendered the prediction an underestimate. Odor identification is superior in women compared with men and declines markedly with age, especially after the sixth decade.14 Therefore, absolute unadjusted numerical UPSIT cutoff scores cannot be used to define abnormality, and age and sex adjustments are needed.14,16 Age-related changes also occur with other markers of MCI and AD dementia: cognitive test performance, MRI atrophy indices, FDG (2-deoxy-2-[18F]fluoro-d-glucose)-PET and amyloid PET abnormalities, and decreased β-amyloid 42 with increased tau and phospho-tau in CSF.31–34 Also, odor identification deficits have limited specificity because they occur in nonspecific anosmia, Parkinson disease, schizophrenia, and alcoholism.16,35,36 These disorders need to be excluded before olfactory testing is used as a predictor of cognitive decline or transition to AD. In addition to AD dementia, odor identification deficits occur in Lewy body dementia and probably vascular dementia,37,38 and therefore cannot be used to subtype dementia diagnosis. The value of biomarkers will improve when more effective treatments for AD dementia are developed. Nonetheless, accuracy in predicting AD dementia can be useful to improve clinical management and to help patients and family members plan for their future.

The UPSIT was stronger than SRT-TR in predicting cognitive decline, and their combination was not superior to the UPSIT alone. Predictive accuracy for cognitive decline was moderate in this community cohort, suggesting that the UPSIT may need to be combined with other measures for use as a screening tool to identify individuals at risk of cognitive decline in the general population.

Clinicians consider age, education, cognitive test performance, and functional ability when evaluating patients with suspected cognitive decline, MCI, or AD dementia. This study's findings indicate that odor identification can contribute significantly to prediction over and above the assessment of these measures.4,6 MRI hippocampal volume did not show predictive utility in this cohort, supporting the potential advantage that a relatively inexpensive odor identification test has over expensive procedures to predict future cognitive decline and AD dementia. In the future, odor identification test performance may be a useful measure to select/stratify patients in treatment trials of patients with cognitive impairment, or prevention trials in cognitively intact individuals, because olfactory deficits can predict cognitive decline in cognitively intact individuals and are an early biomarker of AD neuropathology.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank the participants who volunteered for this study and the many staff members who helped to do the study.

GLOSSARY

- AD

Alzheimer disease

- AUC

area under the curve

- CI

confidence interval

- HR

hazard ratio

- MCI

mild cognitive impairment

- ROC

receiver operating characteristic

- RR

relative risk

- SRT

Selective Reminding Test

- SRT-TR

Selective Reminding Test–total immediate recall

- UPSIT

University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test

- WHICAP

Washington Heights/Inwood Columbia Aging Project

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

D.P. Devanand, Yaakov Stern, and Richard Mayeux designed the study. D.P. Devanand, Jennifer Manly, Nicole Schupf, Howard Andrews, and Elan Louis oversaw the data collection. Seonjoo Lee performed the statistical analyses. D.P. Devanand drafted the manuscript, and all authors contributed to data interpretation and writing the article.

STUDY FUNDING

The study was supported by grants AG007232, AG029949, and AG17761 awarded by the National Institute of Aging, USA. The funding source, National Institute of Aging, had no role in the design and conduct of the study, collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data; preparation, review or approval of the manuscript, and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

DISCLOSURE

D. Devanand has received consulting fees from AbbVie and Lundbeck. S. Lee, J. Manly, H. Andrews, and N. Schupf report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. R. Doty is president and major shareholder of Sensonics, Inc., a manufacturer and distributor of tests of taste and smell, including the UPSIT. Dr. Richard Doty has received publishing royalties from Cambridge University Press and Johns Hopkins University Press, an honorarium from the University of Florida, and lodging reimbursement as chairperson of the Other Non-Motor Features of Parkinson's Disease working group of the Parkinson Study Group, and consulting fees from Pfizer, Inc., Acorda Therapeutics, and several law offices. Y. Stern, L. Zahodne, E. Louis, and R. Mayeux report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Go to Neurology.org for full disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hyman BT, Arriagada PV, Van Hoesen GW. Pathologic changes in the olfactory system in aging and Alzheimer's disease. Ann NY Acad Sci 1991;640:14–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilson RS, Arnold SE, Schneider JA, Tang Y, Bennett DA. The relationship between cerebral Alzheimer's disease pathology and odour identification in old age. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2007;78:30–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Doty RL, Reyes PF, Gregor T. Presence of both odor identification and detection deficits in Alzheimer's disease. Brain Res Bull 1987;18:597–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tabert MH, Liu X, Doty RL, et al. A 10-item smell identification scale related to risk for Alzheimer's disease. Ann Neurol 2005;58:155–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Djordjevic J, Jones-Gotman M, De Sousa K, Chertkow H. Olfaction in patients with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging 2008;29:693–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Devanand DP, Liu X, Tabert MH, et al. Combining early markers strongly predicts conversion from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer's disease. Biol Psychiatry 2008;64:871–879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Graves AB, Bowen JD, Rajaram L, et al. Impaired olfaction as a marker for cognitive decline: interaction with apolipoprotein E epsilon4 status. Neurology 1999;53:1480–1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilson RS, Schneider JA, Arnold SE, Tang Y, Boyle PA, Bennett DA. Olfactory identification and incidence of mild cognitive impairment in older age. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2007a;64:802–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Devanand DP, Tabert MH, Cuasay K, et al. Olfactory identification deficits and MCI in a multiethnic elderly community sample. Neurobiol Aging 2010;31:1593–1600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stern Y, Andrews H, Pittman J, et al. Diagnosis of dementia in a heterogeneous population: development of a neuropsychological paradigm-based diagnosis of dementia and quantified correction for the effects of education. Arch Neurol 1992;49:453–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Manly JJ, Bell-McGinty S, Tang MX, Schupf N, Stern Y, Mayeux R. Implementing diagnostic criteria and estimating frequency of mild cognitive impairment in an urban community. Arch Neurol 2005;62:1739–1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levy G, Tang MX, Cote LJ, et al. Motor impairment in PD: relationship to incident dementia and age. Neurology 2000;55:539–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Rijk MC, Breteler MM, den Breeijen JH, et al. Dietary antioxidants and Parkinson disease: the Rotterdam Study. Arch Neurol 1997;54:762–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Doty RL, Shaman P, Applebaum SL, Giberson R, Siksorski L, Rosenberg L. Smell identification ability: changes with age. Science 1984;226:1441–1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doty RL, Frye RE, Agrawal U. Internal consistency reliability of the fractionated and whole University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test. Percept Psychophys 1989;45:381–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murphy C. Olfactory functional testing: sensitivity and specificity for Alzheimer's disease. Drug Dev Res 2002;56:123–131. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Manly JJ, Tang MX, Schupf N, Stern Y, Vonsattel JP, Mayeux R. Frequency and course of mild cognitive impairment in a multiethnic community. Ann Neurol 2008;63:494–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Siedlecki KL, Manly JJ, Brickman AM, Schupf N, Tang MX, Stern Y. Do neuropsychological tests have the same meaning in Spanish speakers as they do in English speakers? Neuropsychology 2010;24:402–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brickman AM, Schupf N, Manly JJ, et al. Brain morphology in older African Americans, Caribbean Hispanics, and whites from northern Manhattan. Arch Neurol 2008;65:1053–1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pepe M, Longton GM, Janes H. Estimation and comparison of receiver operating characteristic curves. Stata J 2008;9:1. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Youden WJ. Index for rating diagnostic tests. Cancer 1950;3:32–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Watfa G, Husson N, Buatois S, Laurain MC, Miget P, Benetos A. Study of Mini-Mental State Exam evolution in community-dwelling subjects aged over 60 years without dementia. J Nutr Health Aging 2011;15:901–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schubert CR, Carmichael LL, Murphy C, Klein BE, Klein R, Cruickshanks KJ. Olfaction and the 5-year incidence of cognitive impairment in an epidemiological study of older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2008;56:1517–1521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Swan GE, Carmelli D. Impaired olfaction predicts cognitive decline in nondemented older adults. Neuroepidemiology 2002;21:58–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilson RS, Arnold SE, Tang Y, Bennett DA. Odor identification and decline in different cognitive domains in old age. Neuroepidemiology 2006;26:61–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Calhoun-Haney R, Murphy C. Apolipoprotein epsilon4 is associated with more rapid decline in odor identification than in odor threshold or Dementia Rating Scale scores. Brain Cogn 2005;58:178–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Olofsson JK, Rönnlund M, Nordin S, Nyberg L, Nilsson LG, Larsson M. Odor identification deficit as a predictor of five-year global cognitive change: interactive effects with age and ApoE-epsilon4. Behav Genet 2009;39:496–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cosentino S, Scarmeas N, Helzner E, et al. APOE epsilon 4 allele predicts faster cognitive decline in mild Alzheimer disease. Neurology 2008;70:1842–1849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Conti MZ, Vicini-Chilovi B, Riva M, et al. Odor identification deficit predicts clinical conversion from mild cognitive impairment to dementia due to Alzheimer's disease. Arch Clin Neuropsychol 2013;28:391–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Price JL, McKeel DW, Jr, Buckles VD, et al. Neuropathology of nondemented aging: presumptive evidence for preclinical Alzheimer disease. Neurobiol Aging 2009;30:1026–1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kantarci K, Senjem ML, Lowe VJ, et al. Effects of age on the glucose metabolic changes in mild cognitive impairment. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2010;31:1247–1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Erten-Lyons D, Dodge HH, Woltjer R, et al. Neuropathologic basis of age-associated brain atrophy. JAMA Neurol 2013;70:616–622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scheinin NM, Wikman K, Jula A, et al. Cortical 11C-PIB uptake is associated with age, APOE genotype, and gender in “healthy aging.” J Alzheimers Dis 2014;41:193–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mattsson N, Rosén E, Hansson O, et al. Age and diagnostic performance of Alzheimer disease CSF biomarkers. Neurology 2012;78:468–476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Doty RL, Kamath V. The influences of age on olfaction: a review. Front Psychol 2014;5:20. 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.0020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Murphy C, Schubert CR, Cruickshanks KJ, Klein BE, Klein R, Nondahl DM. Prevalence of olfactory impairment in older adults. JAMA 2002;288:2307–2312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ross GW, Abbott RD, Petrovitch H, et al. Association of olfactory dysfunction with incidental Lewy bodies. Mov Disord 2006;21:2062–2067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gray AJ, Staples V, Murren K, Dhariwal A, Bentham P. Olfactory identification is impaired in clinic-based patients with vascular dementia and senile dementia of Alzheimer type. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2001;16:513–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]