Abstract

Background

Phosphorylation plays an essential role in regulating the voltage-gated sodium (Nav) channels and excitability. Yet, a surprisingly limited number of kinases have been identified as regulators of Nav channels. Herein, we posited that glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3), a critical kinase found associated with numerous brain disorders, might directly regulate neuronal Nav channels.

Methods

We used patch-clamp electrophysiology to record sodium currents from Nav1.2 channels stably expressed in HEK-293 cells. mRNA and protein levels were quantified with RT-PCR, Western blot, or confocal microscopy, and in vitro phosphorylation and mass spectrometry to identify phosphorylated residues.

Results

We found that exposure of cells to GSK3 inhibitor XIII significantly potentiates the peak current density of Nav1.2, a phenotype reproduced by silencing GSK3 with siRNA. Contrarily, overexpression of GSK3β suppressed Nav1.2-encoded currents. Neither mRNA nor total protein expression were changed upon GSK3 inhibition. Cell surface labeling of CD4-chimeric constructs expressing intracellular domains of the Nav1.2 channel indicates that cell surface expression of CD4-Nav1.2-Ctail was up-regulated upon pharmacological inhibition of GSK3, resulting in an increase of surface puncta at the plasma membrane. Finally, using in vitro phosphorylation in combination with high resolution mass spectrometry, we further demonstrate that GSK3β phosphorylates T1966 at the C-terminal tail of Nav1.2.

Conclusion

These findings provide evidence for a new mechanism by which GSK3 modulate Nav channel function via its C-terminal tail.

General Significance

These findings provide fundamental knowledge in understanding signaling dysfunction common in several neuropsychiatric disorders.

1.1 Introduction

Voltage-gated sodium (Nav) channels are a family of transmembrane proteins consisting of a pore-forming α-subunit (Nav1.1–1.9) and auxiliary β subunits (β1–β4) [1]. In neurons, Nav channels open in response to membrane depolarization allowing the rapid inward flux of Na+ that drives the rising phase of the action potential, a fundamental signaling event in synaptic communication. Both extremes of Nav channel function can be harmful leading to severe disorders [2, 3], suggesting the existence of highly controlled, modulatory mechanisms required to fine-tune the channel activity in vivo.

Phosphorylation plays an essential role in regulating Nav channel function with profound effects on intrinsic excitability and activity-dependent plasticity [4–8]. Extensive evidence indicates that protein kinase C (PKC) and cAMP-dependent kinase (PKA) can phosphorylate brain Nav channels resulting in attenuation of Na+ currents [9–12]. Interestingly, this mechanism is Nav1.2-specific and it is absent in Nav1.6 channels [13]. Additional evidence of a high degree of signal specificity is provided by a recent study reporting that PKCε can phosphorylate Nav1.8 channels, albeit leading to up-regulation of Na+ peak current amplitudes and changes in gating properties [14]. Other kinases involved in regulating Nav channel function are the extracellular-signal-regulated kinases 1/2 (ERK1/2) and p38 mitogen-kinase-activated protein kinases (MAPKs). Inhibition of pERK1/2 has been found to induce a depolarizing shift of activation and fast inactivation of Nav1.7 [15], while p38MAPK phosphorylation suppresses Nav1.6-mediated peak current amplitudes without any detectable effect on gating properties [16].

In addition to modulating kinetics, phosphorylation contributes to the sub-cellular compartmentalization of Nav channels by modifying signaling motifs required for trafficking, targeting and protein degradation [17]. For example, the Nav channel clustering at the axonal initial segment (AIS) depends on phosphorylation of the channel by the protein casein kinase 2 (CK2) through interactions with ankyrins [18]. Phosphorylation of Nav1.6 by p38MAPK might also contribute to spatial segregation and targeting of Nav channels, promoting degradation of the channel from undesired sub-cellular domains [19]. Furthermore, the PKA signaling pathway has been shown to control the surface expression of Nav1.8 through a trafficking motif in the first intracellular loop of the channel [14].

Yet, despite the relevance of phosphorylation in modulating Nav channel function, a surprisingly limited number of kinases have been so far identified as regulators of Nav channels. Furthermore, recent mass spectrometry analyses have revealed fifteen previously unknown phospho-residues on native Nav channels [8, 20], clearly broadening the potential repertoire of kinases connected to Nav channels.

Recently, glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3) has emerged as one of these kinases and has been implicated in possible regulation of ion channels [21]. GSK3 is a highly conserved enzyme abundantly expressed in the brain and found to be involved in a plethora of brain disorders, including Alzheimer’s disease, addiction, bipolar disorder, depression and schizophrenia [22–25]. Studies in bovine adrenal chromaffin cells indicated that inhibition of GKS3 via lithium chloride, up-regulated cell-surface expression of Nav1.7 channels [26]. However, the phenomenon remains complex, as lithium can influence sodium influx through voltage-gated channels independently of GSK3 as well [27].

In this study, we have combined patch-clamp electrophysiology, RT-PCR, Western blot, confocal microscopy, in vitro phosphorylation, and mass spectrometry to characterize a new mechanism through which GSK3 regulates Nav1.2 channels, one of the most abundant Nav channels in the brain [28]. We show that inhibition of GSK3 potentiates Nav1.2 peak amplitude likely whereas overexpression of GSKβ results in suppression, demonstrating bidirectional control of Nav1.2-derived currents by GSK3. Pharmacological inhibition of GSK3 increases the channels at the cell surface through a mechanism likely requiring its C-tail. In vitro phosphorylation experiments of Nav1.2 C-tail (1961–1980) combined with mass spectrometry analysis indicate that the site of GSK3 phosphorylation is T1966. These results provide new evidence for a basic cellular mechanism of relevance for the understanding and treatment of brain disorders.

2.1 Material and methods

2.1.1 Chemicals

GSK3 inhibitor XIII (EMD Chemicals, San Diego, CA) was dissolved in 100% DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) to a working stock concentration of 20mM, aliquoted, and stored at −20 °C. From the working stock, DMSO was further diluted to a final concentration of 0.15% or 0.05% to be used as a vehicle control for 30μM or 10μM GSK3 inhibitor XIII, respectively. DMSO controls in the dose response experiments were adjusted to a final concentration matching the amount of DMSO solvent used for GSK3 inhibitor XIII. For mass spectrometric experiments, LC-MS grade acetonitrile (ACN) and water were from J.T. Baker (Philipsburg, NJ). Formic acid was obtained from Pierce (Rockford, IL) and iodoacetamide (IAA) and dithiothreitol (DTT) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Sequencing grade trypsin was supplied by Promega (Madison, WI).

2.1.2 Cell culture and transient transfections

All reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich unless noted otherwise. HEK-293 cells stably expressing rat Nav1.2 (HEK-Nav1.2 cells, gift from Dr. David Ornitz, Washington University in St. Louis) were maintained in medium composed of equal volumes of DMEM and F12 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 0.05% glucose, 0.5 mM pyruvate, 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 500 μg/ml G418 (Invitrogen) for selection of Nav1.2 stably transfected cells, and incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2, as previously described [29]. COS-7 cells were maintained in a similar fashion. Cells were transfected at 90–100% confluency using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen), according to manufacturer’s instructions. All CD4 chimeras were cloned into PCB6, and they all expressed a portion of the human CD4 protein deleted of its C-terminal tail (CD4ΔC-tail; amino acids 1–396). The CD4ΔC-tail was fused in frame with the intracellular domains of Nav1.2 channel including the I–II loop (amino acids 428–753), the II–III loop (amino acids 984–1203) or the C-terminal tail (amino acids 1777–2005). These constructs were a gift from B. Dargent (INSERM, France) and have been used in previous studies [30]. Full-length rat GSK3β was cloned into pAAV-IRES-GFP and used for transient transfection into HEK-Nav1.2 cells along with pAAV-IRES-GFP for control.

2.1.3 Genetic silencing of GSK3

To selectively silence GSK3, siRNA against GSK3 α/β (siRNA 6301, Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA) was obtained in its fluoroscein-conjugated form (gift from Cell Signaling) along with scrambled siRNA used as negative control (Control siRNA 6201, fluoroscein-conjugate, Cell Signaling). The knockdown efficiency of GSK3 upon siRNA treatment was determined in previous studies [31] and illustrated in Fig. 2C. For knockdown experiments, HEK-Nav1.2 cells were plated in 6- or 24-well plates (50% confluency) and incubated 1 day later with 10 μl of GSK3-siRNA or negative control siRNA (both from a 10 μM stock) using RNAiMAX (Invitrogen) at a ratio of 10:5 (μl/μl) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Two days later, cells were replated in either 24- or 96-well plates then transfected 2 days later with a second pulse of siRNA. Patch-clamp recordings were performed 24 h after the second siRNA pulse.

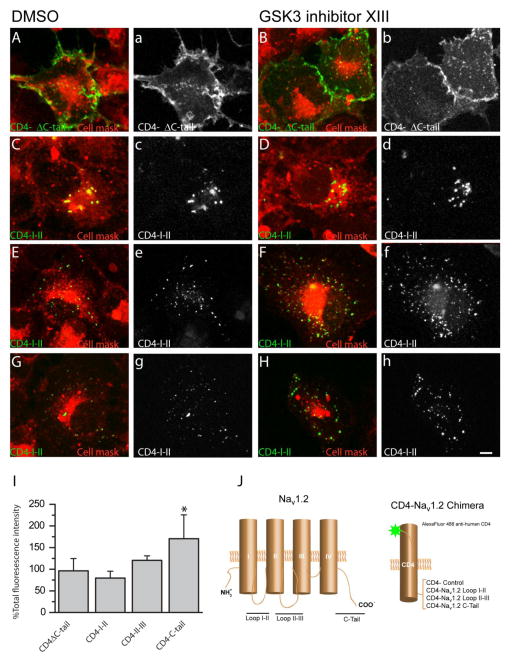

Figure 2. Genetic silencing of GSK3 potentiates Nav1.2-encoded peak current densities.

Representative traces (A) of Nav1.2-derived currents under scrambled RNA conditions (left) or siRNA targeted to GSK3 (right). A current-voltage relationship graph (B) demonstrates the potentiation seen with genetic silencing of GSK3 (red) when compared to scramble control (black). Validation of the RNA construct with Western blot of total cell lysate probed using the indicated antibody is shown in C (reprinted from [29] with permission). A summary bar graph represents the mean current density at 0 mV for both conditions (D). The voltage-dependence of activation and voltage-dependence of steady-state inactivation are shown in E and F, respectively. Results are summarized in Table 1. *(p<0.05).

2.1.4 Electrophysiology

HEK-Nav1.2 cells stably expressing the channel were dissociated and re-plated at low-density. Recordings were performed at room temperature (20–22 °C using an Axopatch 200A amplifier (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA), and GSK3 inhibitor XIII or DMSO were added to the bath solution prior to transfer. Cells were allowed to rest in solution, exposed to the drug or vehicle, for approximately 30 minutes before beginning experiments. Recording continued after this period for one hour, resulting in 1.5 hours of exposure to drugs. Borosilicate glass pipettes with resistance of 3–8 MΩ were made using a Narishige PP-83 vertical Micropipette Puller (Narishige International Inc., East Meadow, NY). The recording solutions were as follows: extracellular (mM): 140 NaCl, 3 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 1 CaCl2, 10 HEPES, 10 glucose, pH 7.3; intracellular: 130 CH3O3SCs, 1 EGTA, 10 NaCl, 10 HEPES, pH 7.3. Membrane capacitance and series resistance were estimated by the dial settings on the amplifier. Individual membrane capacitance (~9pF average) was used to calculate current density in order to compare cells of all sizes, and cells exhibiting a series resistance of 25MΩ or higher were excluded from analysis. Capacitive transients and series resistances were compensated electronically by 70–80%. Data were acquired at 20 kHz and filtered at 5 kHz prior to digitization and storage. All experimental parameters were controlled by Clampex 7 software (Molecular Devices) and interfaced to the electrophysiological equipment using a Digidata 1200 analog–digital interface (Molecular Devices). Voltage-dependent inward currents were evoked by depolarizations to test potentials between −60 mV and +60 mV from a holding potential of −90 mV. Steady-state (fast) inactivation of Nav channels was measured with a paired-pulse protocol. From the holding potential, cells were stepped to varying test potentials between −110 mV and 20 mV (prepulse) prior to a test pulse to −10 mV.

2.1.5 Electrophysiology data analysis

Current densities were obtained by dividing Na+ current (INa) amplitude by membrane capacitance. Current–voltage relationships were generated by plotting current density as a function of the holding potential. Conductance (GNa) is calculated by the following Equation 1:

where INa is the current amplitude at voltage Vm, and Erev is the Na+ reversal potential.

Steady-state activation curves were derived by plotting normalized GNa as a function of test potential and fitted using the Boltzmann Equation 2:

where GNa,Max is the maximum conductance, Va is the membrane potential of half-maximal activation, Em is the membrane voltage and k is the slope factor. For steady-state inactivation, normalized current amplitude (INa/INa,Max) at the test potential was plotted as a function of prepulse potential (Vm) and fitted using the Boltzmann Equation 3:

where Vh is the potential of half-maximal inactivation and k is the slope factor.

Data analysis was performed using Clampfit 9 software (Molecular Devices, USA) and Origin 8.6 software (OriginLab, Northampton, MA, USA).

2.1.6 RT-PCR

RNA was prepared from HEK-Nav1.2 cells treated with either DMSO (0.15%) or GSK3 inhibitor XIII (30 μM). RNA extraction was performed with a Qiagen RNEasy extraction kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), and cDNA was prepared using the Superscript III First Strand kit (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. PCR amplification used ~10 μg cDNA in a 20 μl reaction volume with the primers listed below. GAPDH was used for loading control and standardization, and a melt curve was used to confirm the presence of a single amplicon. Amplification cycles of PCR (40) were performed on an Applied Biosystems 7500 fast thermocycler (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), and cycling temperatures and times were as follows: 95°C, 15s; 60°C, 30s; 72°C, 45s. Primer sequences for rat Nav1.2 were: forward 5′-GCCAGACCATGTGCCTTACT-3′ and reverse 5′-CATCCTTCCCACGGCTATC-3′.

2.1.7 Western Blotting

HEK-Nav1.2 cells treated for 1 h at 37 °C with GSK3 inhibitor XIII (30 μM) or DMSO (0.15%) were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and lysed in buffer containing (in mM) 20 Tris-HCl, 150 NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40. Protease inhibitor mixture Set 3 (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) was added immediately before cell lysis. Cell extracts were collected and sonicated for 20 s and then centrifuged at 4° at 15,000×g for 15 min. Supernatant was mixed with 4×sample buffer containing 50 mM tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine, and mixtures were heated for 10 min at 55°C and resolved on 4–15% polyacrylamide gels (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Resolved proteins were transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA) for 1.5–2 h at 4°C, 75 V and blocked in TBS with 3% nonfat dry milk and 0.1% Tween 20. Membranes were then incubated in blocking buffer containing primary mouse monoclonal anti-PanNav channel (1:1000; Sigma) overnight. After washing, membranes were incubated with a secondary HRP goat anti-mouse antibody for 2 h. Membranes were then washed and incubated with a primary rabbit anti-calnexin antibody (Cell Signaling Technology) and then with a goat anti-rabbit HRP antibody (1:5000–10,000; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Protein bands were detected with ECL Advance Western blotting Detection kit (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK), visualized using FluorChem® HD2 System and analyzed with AlphaView 3.1 software (ProteinSimple, Santa Clara, CA).

2.1.8 Immunocytochemistry

HEK-Nav1.2 cells were treated with either GSK3 inhibitor XIII (30 μM) or DMSO (0.15%) for 1 h and then fixed in fresh 4% paraformaldehyde and 4% sucrose in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 15 min. Following permeabilization with 0.25% Triton X-100 and blocking with 10% BSA for 30 min at 37 °C, cells were incubated overnight at room temperature with a primary mouse anti-PanNav (1:100; Sigma) diluted in PBS containing 3% BSA. Cells were then washed 3× in PBS, incubated for 45 min at 37° C with a goat anti-mouse Alexa-568 conjugated secondary antibody and stained with the nuclear marker TOPRO-3 (both from Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Coverslips were then washed 6× with PBS and mounted on glass slides with Prolong Gold anti-fade reagent (Life Technologies).

2.1.9 Surface labeling

COS-7 cells, transiently transfected with CD4 chimeras, were incubated for 1 hour at 37°C with DMSO (0.1%) or GSK3 inhibitor XIII (20 μM) solutions in fresh cell media without serum. Then, cells were treated at room temperature for 20 minutes with an Alexa 488-conjugated anti-human CD4 antibody at 0.5 μl/ml final concentration (catalog # 317419, Biolegend, San Diego, CA). Following washes and fixation, HCS Cell Mask Deep RED plasma membrane stain (Life Technologies) was applied to label the cell contour according to manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were then mounted using Prolong Gold.

2.1.10 Image analysis

Confocal images were acquired with a Zeiss LSM-510 Meta confocal microscope with a 63× oil immersion objective (1.4 NA). Multi-track acquisition was done with excitation lines at 488 nm for Alexa 488, 543 nm for Alexa 568, and 633 nm for Alexa 647. Respective emission filters were band-pass 505–530 nm, band-pass 560–615 nm and low-pass 650. In all experiments optical slices were 0.7 μm with a frame size of 512×512, pixel time of 2.51 μs, pixel size of 0.28×0.28 μm, and a 4-frame Kallman–averaging. All acquisition parameters, including photomultiplier gain and offset, were kept constant throughout each batch of experiments. The summed projections of the image stacks were analyzed using FIJI (NIH). The total pool of Na+ channels was quantified by measuring the fluorescent intensity relative to PanNav antibodies in the cells. Cells were segmented using a binary threshold followed by mask refinement using morphological operators. The binary masks were used to compute intensity information of the original image. Normalization of the fluorescence intensity was performed by calculating the ratio of the total integrated intensity over the area of each segmented object. For the analysis of the puncta, an automated algorithm to detect the puncta in a cell, count their number and measure their fluorescent intensity value relative to background was custom made using MatLab (The MathWorks, Inc. Natick, MA). The algorithm consists of two basic steps: preprocessing and blob detection. The denoising routine is based on a shearlet-based multiscale decomposition and adaptive thresholding [32, 33]. The blob detection is based on the application of the Laplacian of Gaussian [34]. Data were tabulated and analyzed with Microsoft Excel, Origin 8.6 (OriginLab, Northampton, Massachusetts), and SigmaStat (Jendel Corporation, San Rafael, CA).

2.1.11 Statistical analysis

Results were expressed as mean ± standard error (SEM). The statistical significance of observed differences among groups was determined by Student’s t-test unless otherwise indicated. A p-value lower than 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant. Experiments performed in Fig. 6 were analyzed using Student’s t-test because the experimental design was such that the effect of the GSK3 inhibitor was exclusively compared to its own internal DMSO control.

Figure 6. The Nav1.2 C-tail is responsible for redistribution after GSK3 inhibition.

Confocal images of COS-7 cells expressing CD4-Nav1.2 chimeras and CD4-ΔC-tail visualized with an Alexa-488-conjugated anti-human CD4 antibody (green) with an HCS Cell Mask™ Deep Red Plasma membrane Stain (red) for reference. Overlay images of PanNav and cell mask are shown in A–H with the following four chimeras shown: CD4-ΔC-tail (A,B), CD4-Nav1.2-I-II loop (C,D), CD4-Nav1.2-II-III loop (E,F), and CD4-Nav1.2-C-tail (G,H). Surface labeling of the CD-4 constructs are shown in grayscale (a–h). A summary bar graph (I) details the percent change in total fluorescence intensity after GSK3 inhibition. Note that the CD4-C-tail construct was the only one significantly affected by GSK3 inhibition. ** (p=0.002). Experiments were analyzed using Student’s t-test because the experimental design was such that the effect of the GSK3 inhibitor was exclusively compared to its own internal DMSO control.

2.1.12 Peptide Synthesis

Nav1.2 peptide EKTDVTPSTTSPPSYDSVTK, which represents amino acids 1961–1980 in the C-terminus was synthesized using standard Fmoc Chemistry on a CS Bio-CS336X solid phase peptide synthesizer. Rink Amide MBHA or Wang resin was swelled in dry DMF for 1hr, and peptides were double coupled using HBTU (O-(Benzotriazol-1-yl)-N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate) and HOBt (1-Hydroxybenzotriazole) chemistries. Peptides were cleaved from the resin using 95% TFA/2.5% water/2.5% triisopropyl silane cocktail and washed in diethyl ether. Peptide mass was confirmed by MALDI using α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid matrix (Bruker Daltonics, MA). All peptides were lyophilized and stored at 4°C until use.

2.1.13 In vitro Phosphorylation and Sample Preparation

Glycogen Synthase Kinase 3 (#P6040L; New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA) in vitro phosphorylation was performed on the peptide according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Control experiments were conducted in the same way only without the kinase added to the reaction solution. Next, samples were reduced with 10 mM DTT, alkylated with 5 mM IAA, and digested with modified sequencing grade trypsin 1:50 (w/w) overnight at 37°C. Digested samples were desalted on C8 Sep-Pak SPE columns (Waters, Milford, MA) and the eluant was dried to completeness in vacuo.

2.1.14 Mass Spectrometry

Lyophilized peptide samples were resuspended in 0.1% FA/5% ACN (v/v). Chromatographic separations and mass spectrometric data acquisition was performed with a nanoLC-MS/MS (EasyLC-1000 Proxeon Biosystems, Odense, Denmark) coupled to a hybrid mass spectrometer consisting of a linear quadrupole ion trap and an Orbitrap (LTQ-Orbitrap Elite, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Peptides were loaded, in a block randomized manner [35], onto a 100 μm ID × 2 cm C18 trap column (ThermoFisher) and eluted (250 nL/min) and eluted over a PicoFrit® (360 μm OD x 75 μm ID x15 μm) column packed with 10 cm ProteoPep II (5 μm, 300 Å, C18, New Objective). The gradient was as follows: isocratic at 5% B 0–5 min; 5% to 35% B over 45 min; 35% to 95% B over 5 min; and isocratic at 95% B for an additional 5 min. Mobile phases were 0.1% FA in water (A) and 0.1% FA in ACN (B). Total run time, including column equilibration, sample loading, and analysis was 85 min. Survey scans (MS) (m/z 300–2000) were acquired at high-resolution in the Orbitrap at 60,000 resolution (at m/z 400) in profile mode followed by isolation and fragmentation (MS/MS) of the five most abundant precursor ions above a 1,000 counts threshold in the Orbitrap by HCD (isolation width 4.0 Da, default charge state of 4, normalized collision energy 30%, activation Q 0.250, and activation time 10 ms; 15,000 resolution at m/z 400). Instrument parameters were as follows: 500 ms ion injection times for both MS and MS/MS scans; AGC targets of 1 x 106 for MS and 2 x 105 for MS/MS; dynamic exclusion (±10 ppm relative to precursor ion m/z) enabled with a repeat count of 1, maximal exclusion list size of 500, and an exclusion duration of 30 s; monoisotopic precursor selection (MIPS) was enabled and unassigned ions were rejected; spray voltage 2.1 kV, 40% S-lens, and capillary temperature 275°C. Spectra were acquired using XCalibur, version 2.7 SP1 (ThermoFisher).

2.1.15 Data Analysis for Mass Spectrometry

Raw mass spectrometric files were imported into PEAKS (version 6, Bioinformatics Solutions Inc., Waterloo, ON) and search against a merged UniprotKB/SwissProt RatMouse database of canonical sequences (March 2014; 24,541 entries) appended with the cRAP contaminant database (February 2012 version, The Global Proteome Machine, www.thegpm.org/cRAP/index.html). Precursor ion mass tolerance was set to 10 ppm and fragment mass tolerance was 0.1 Da. A maximum of two missed cleavages were allowed using trypsin as the endoprotease; carbamidomethylation of cysteine and N-terminal acetylation were set as fixed modifications. Oxidation of methionine and phosphorylation of serine, tyrosine, and threonine were set as variable modifications. Identification and site localization of phosphorylation sites was conducted by manual annotation.

3.1 Results

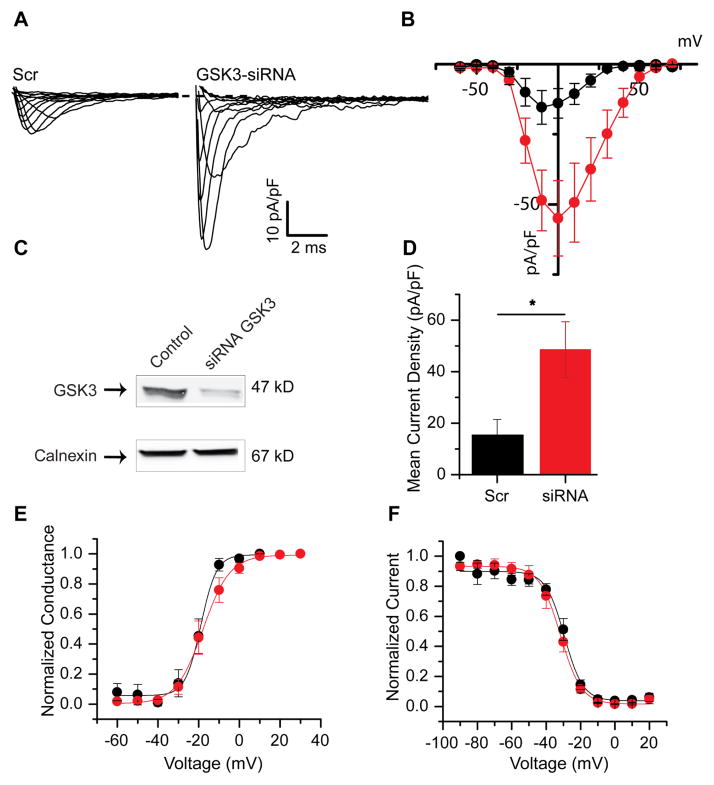

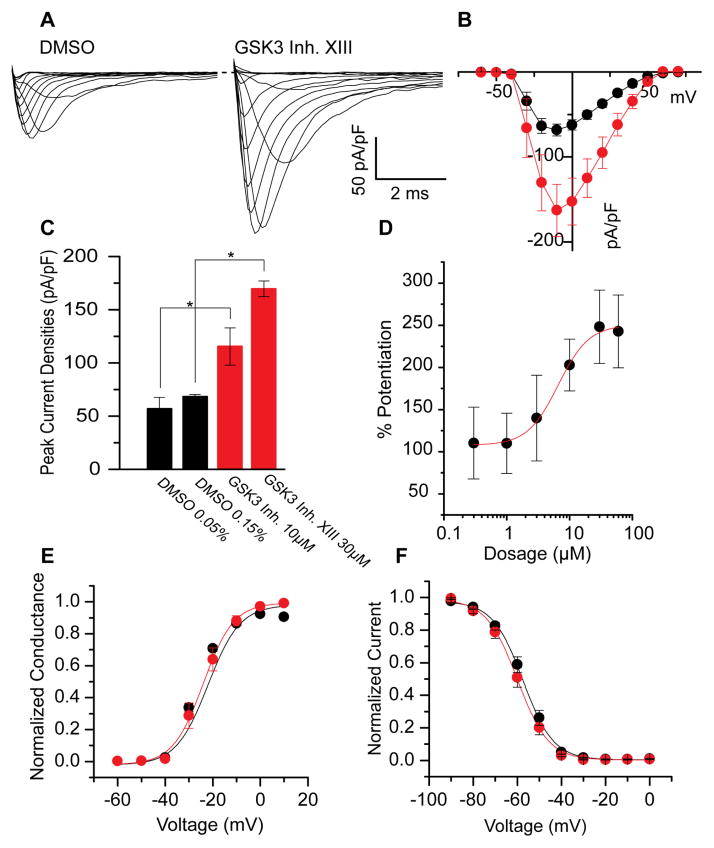

3.1.1 GSK3 inhibitor XIII potentiates Nav1.2 peak current densities

To determine whether pharmacological inhibition of GSK3 affects Nav channel function, HEK293 cells stably expressing the rat Nav1.2 channel (HEK-Nav1.2) were exposed for approximately 1 hour to either vehicle (DMSO) or GSK3 inhibitor XIII prior to whole-cell patch clamp recording [29]. As shown in Fig. 1A, rapid rising and fast decaying transient inward Na+ currents encoded by Nav1.2 were evoked in response to depolarizing voltage steps. In cells pretreated with GSK3 inhibitor XIII (30μM) the Nav1.2-mediated peak current density was significantly higher (−169.7 ± 29.8 pA/pF, n=11, p<0.005) compared to control (−68.37 ± 7 pA/pF, n=8; Fig. 1A–C). We found similar effects on potentiation using a smaller dose (10μM) of GSK3 inhibitor XIII—peak current densities were increased from −56.9 ± 10.6 pA/pF (n=10) in the DMSO control to −115.4 ± 17.5 pA/pF (n=14, p<0.01 with Mann-Whitney rank sum test, Fig. 1C). Additionally, using a range of doses from 0.3μM to 60μM, we developed a dose-response profile of HEK-Nav1.2 cells in the presence of GSK3 inhibitor XIII (Fig. 1D). The inhibitor does exhibit dose-dependent potentiation of Nav1.2 encoded currents that exhibits an EC50 of 6.6 ± 0.8μM. Minimal differences between 30μM and 60μM indicate the phenotype does saturate at higher concentrations.

Figure 1. Pharmacological inhibition of GSK3 leads to potentiated Nav1.2 peak current densities.

Representative traces (A) of Nav1.2-mediated currents under 0.15% DMSO conditions (left) or 30 μM GSK3 inhibitor XIII (right). A current-voltage relationship graph (B) demonstrates the potentiation seen with addition of GSK3 inhibitor (red) when compared to DMSO (black). A bar graph represents the mean current density at −10 mV for 30μM and 10μM (C). D shows the dose-dependent potentiation of Nav1.2- encoded currents in response to varying concentrations of GSK3 inhibitor XIII (0.3μM to 60μM). The voltage-dependence of activation and voltage-dependence of steady-state inactivation at 30μM are shown in E and F, respectively. Results are summarized in Table 1. *(p<0.05).

Additional analyses were performed to examine the effect of GSK3 inhibitor XIII on the voltage-dependence properties of activation and steady-state inactivation of Nav1.2 channels (Fig. 1E,F). Analysis of the activation profile revealed no statistically significant changes in the voltage-dependence of activation upon treatment with GSK3 inhibitor XIII (Fig. 1E, Table 1). The V1/2 of activation in the GSK3 inhibitor XIII group was −23.1 ± 0.3 mV (n=16) compared to −25.5 ± 1.7 mV (n=13) in the control group. These two groups did not significantly differ (p=0.34). To determine whether GSK3 affects the steady-state inactivation properties of Nav1.2 channels, cells from the two experimental groups were subjected to a standard two-step protocol including a pre-step conditioning pulse followed by a variable test pulse (Fig. 1F). Cells treated with GSK3 inhibitor XIII exhibited a V1/2 of −59.8 ± 0.5 mV (n=15), which was not significantly different (p=0.27) from the DMSO value of −57.5 ± 0.5 mV (n=15). In the 10μM experiments, a statistically significant depolarizing shift was detected in the voltage-dependence of activation in DMSO (−30.4 ± 2.4 mV, n=10) versus the GSK3 inhibitor-treated group (−19.4 ± 2.1 mV, n=14, p<0.01, Mann-Whitney rank sum test). Further, a depolarizing shift was detected in the voltage-dependence of steady-state inactivation in DMSO control (−63.8 ± 0.5 mV, n=9) versus the GSK3 inhibitor-treated group (−54.1 ± 5.4 mV, n=15, p<0.01, Mann-Whitney rank sum test). Results are summarized in Table 1. Taken together, these data demonstrate a robust potentiation of Nav1.2-mediated peak current densities upon a rapid pharmacological inhibition of GSK3 that is consistent and dose-dependent. Additionally, changes in the biophysical properties of the channel are detected at concentration near the EC50, suggesting a complex mechanism of regulation induced by pharmacological inhibition of GSK3.

Table 1.

| Condition | Peak density (pA/pF) | Activation V1/2 (mV) | kact (mV) | Inactivation V1/2 (mV) | kinact (mV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DMSO (0.15%) | −68.4 ± 2.0 (13) | −25.5 ± 1.7 (13) | 4.0 ± 1.4 (13) | −57.5 ± 0.5 (15) | 6.1 ± 0.4 (15) |

| GSK3 Inh. XIII (30μM) | −170.0 ± 7.4 (16)* | −23.1 ± 0.3 (16) | 4.0 ± 0.3 (16) | −59.8 ± 0.5 (15) | 5.8 ± 0.4 (15) |

| DMSO (0.05%) | −56.9 ± 10.6 (10) | −30.4 ± 2.4 (10) | 4.3 ± 0.4 (10) | −63.8 ± 1.6 (9) | 6.6 ± 0.2 (9) |

| GSK3 Inh. XIII (10μM) | −115.4 ± 17.5 (14)* | −19.4 ± 2.1 (14)* | 4.0 ± 0.5 (14) | −54.1 ± 5.4 (15)* | 5.4 ± 0.2 (15) |

| Scrambled RNA | −15.4 ± 6.0 (7) | −19.2 ± 2.4 (5) | 4.0 ± 1.9 (5) | −30.0 ± 1.9 (7) | 6.0 ± 2.1 (7) |

| GSK3-siRNA | −48.6 ± 10.8 (8)* | −17.2 ± 0.5 (8) | 4.7 ± 0.7 (7) | −34.2 ± 1.8 (8) | 5.6 ± 1.5 (8) |

| IRES-GFP | −148.1 ± 17.3 (8) | −21.2 ± 4.6 (8) | 3.4 ± 0.5 (8) | −55.1 ± 1.4 (8) | 5.3 ± 0.2 (8) |

| GSK3β-IRES-GFP | −79.0 ± 18.3 (11)* | −19.2 ± 4.5 (11) | 4.7 ± 0.2 (11) | −59.7 ± 1.6 (11) | 6.4 ± 0.3 (11)* |

p<0.05, data are presented as mean ± SEM, parenthesis indicate number of cells in group

3.1.2 Genetic silencing of GSK3 potentiates Nav1.2 peak current densities

To provide further validation of our findings, we silenced GSK3 using siRNA-driven knockdown. HEK-Nav1.2 cells were transfected with fluorescein-conjugated siRNA targeting GSK3 or a fluorescein-conjugated siRNA scrambled control. Fast inward Na+ currents were evoked in fluorescein-positive cells in response to depolarizing voltage steps (Fig. 2A,B). Notably, treatment with GSK3-siRNA resulted in potentiated peak current densities of −86.6 ± 24.2 pA/pF (n=9) compared to the scrambled control group (−26.2 ± 14.1 pA/pF, n=8, p=0.03, Fig. 2D). GSK3-siRNA-transfected cells exhibited a V1/2 of −20.8 ± 1.7 mV (n=5) for its activation profile (Fig. 2E), and this value did not significantly differ from the scrambled control value of -17.7 ± 1.0 mV (n=5, p=0.17, Table 1). Furthermore, the voltage-dependence of steady-state inactivation in the GSK3-siRNA cells (V1/2 of −55.0 ± 1.8 mV, n=4, Fig. 2F) was not statistically different from control cells (V1/2 of −56.4 ± 1.7 mV, n=4, p=0.57, Table 1). It should be noted that the peak current density values for scramble and GSK3-siRNA treated cells were overall smaller than the values reported for DMSO and GSK3 inhibitor XIII. However, the % potentiation of Nav1.2-encoded currents was similar in the two categories with a ~2.5 increase upon pharmacological inhibition and a ~3 upon silencing. Given that no other morphological or physiological differences were observed in the siRNA group, the difference in the magnitude of Nav1.2 currents in these two experimental groups might be attributed to the transfection process for siRNA. Overall, these results corroborate the hypothesis that inhibition of GSK3, either upon pharmacological treatment or genetic silencing, leads to a potentiation of Nav1.2-encoded current densities.

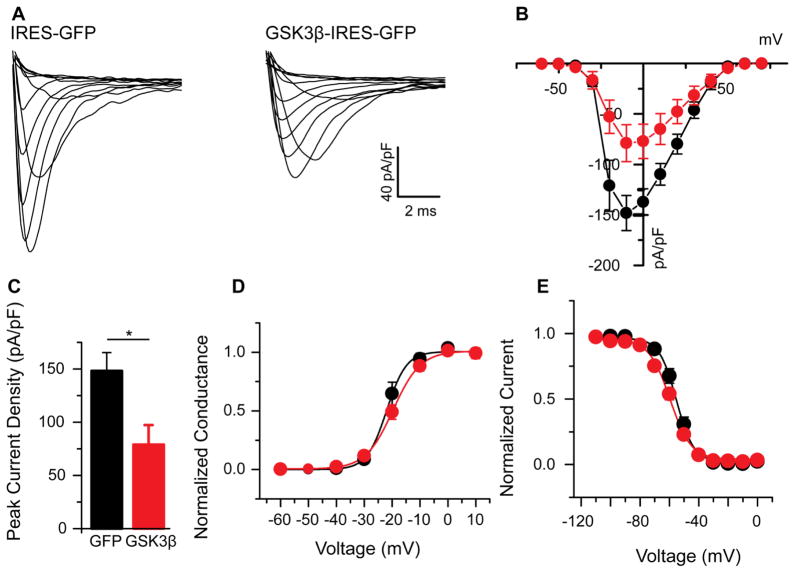

3.1.3 GSK3β overexpression suppresses Nav1.2 current densities

After exploring the effects of GSK3 silencing, we next examined the potential bidirectionality of GSK3 regulation of the Nav1.2 channel. HEK-Nav1.2 cells were transfected with a GSK3β-overexpressing vector using an internal ribosomal entry site (IRES) directed GFP reporter, while the IRES-GFP construct was used alone as a control. Cells transfected with the IRES-GFP for control displayed an average Nav1.2-encoded current density of −148.1 ± 17.3 pA/pF (n=8), which was suppressed to −79.0 ± 18.3 pA/pF (n=11, p=0.02) in cells receiving the GSK3β-overexpressing vector (Fig 3A–C). Kinetically, cells did not significantly differ (Fig. 3D,E, Table 1). Voltage dependence of activation for control cells (V1/2 of −21.2 ± 4.6 mV, n=8) did not significantly change in cells treated with overexpressing vector (V1/2 of −19.2 ± 4.5, n=11, p=0.37). Similarly, the voltage dependence of steady-state inactivation for control cells (V1/2 of −55.1 ± 1.4 mV, n=8) did not significantly differ from the V1/2 of −59.7 ± 1.6 (n=11, p=0.05). These data indicate further that GSK3 regulates the Nav1.2 channel in a likely bidirectional manner, resulting in an opposite phenotype from inhibition of GSK3. Additionally, the exclusivity of the construct in expressing GSK3β lends support to the hypothesis that GSK3β may be the primary mediator of the effects observed in this study, favored over its isoform GSK3α.

Figure 3. Overexpression of GSK3β suppresses Nav1.2-encoded peak current densities.

Representative traces (A) of sodium currents in HEK-Nav1.2 cells transfected with IRES-GFP (left) or GSK3β-IRES-GFP (right). A current-voltage relationship graph (B) demonstrates the suppression seen with overexpression of GSK3β (red) when compared to GFP control (black). A summary bar graph represents the mean current density at −10mV for both conditions (C). The voltage-dependence of activation and voltage-dependence of steady-state inactivation are shown in D and E, respectively. Results are summarized in Table 1. *(p<0.05).

3.1.4 GSK3 inhibition does not affect Nav1.2 transcripts or total protein levels of Nav1.2

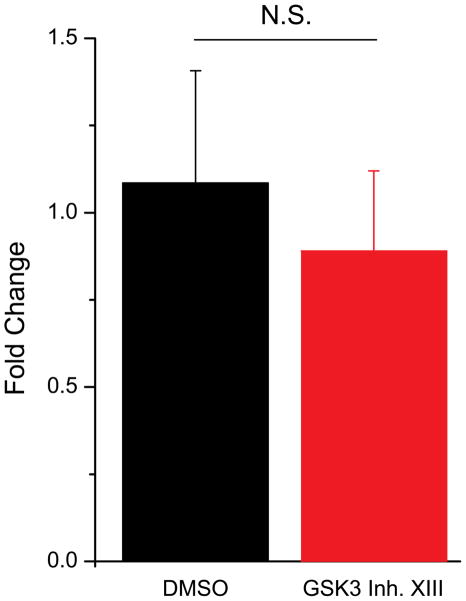

Next, we examined whether changes at either the mRNA or total protein level could account for the increased peak current density we observed. In order to explore this possibility, we first used quantitative RT-PCR in HEK-Nav1.2 cells to determine whether 1h exposure to GSK3 inhibitor XIII (30 μM) induced any change in the levels of Nav1.2 transcript. As shown in Fig. 4, inhibition of GSK3 did not produce a significant fold change of Nav1.2 mRNA compared to control (89% of control, n=3 independent experiments, three replicates each, p=0.65).

Figure 4. GSK3 inhibition does not affect the mRNA levels of Nav1.2.

RT-PCR of HEK-Nav1.2 cells treated with either DMSO or GSK3 inhibitor XIII (30 μM). No significant fold change was detected between DMSO and inhibitor-treated cells (p=0.65). NS= non-statistically significant.

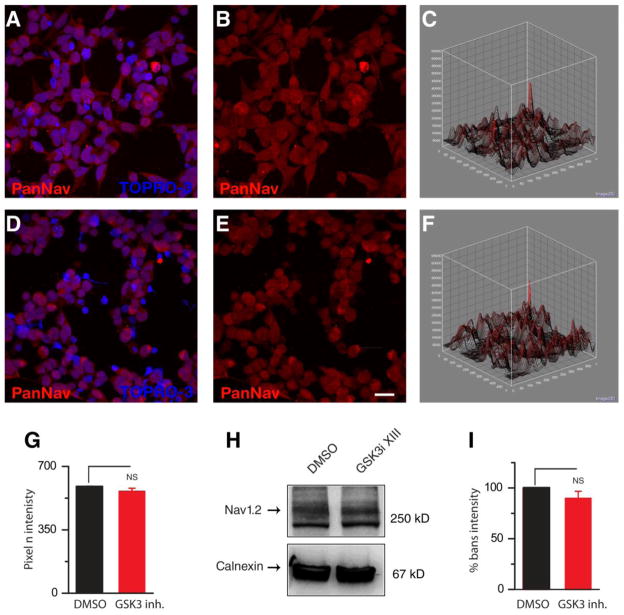

Total protein expression levels could change independently of mRNA as a result of increased protein stability and reduced degradation. Thus, we used quantitative immunofluorescence and Western blot analysis to determine whether 1 h treatment with GSK3 inhibitor XIII (30 μM) changed the total pool of Nav1.2 channels in HEK-Nav1.2 cells. As illustrated in Fig. 5A–F, the PanNav fluorescent intensity corresponding to Nav1.2 in cells exposed to GSK3 inhibitor XIII was visually indistinguishable from the DMSO group. Further quantification on sum projected confocal images over a large population of cells indicated that the mean fluorescence values corresponding to Nav1.2 immunofluorescence in the GSK3 inhibitor XIII group was not statistically different from the DMSO control (p<0.3, n=3,466 cell mask counts in DMSO compared to n=2,895 in the GSK3 inhibitor XIII group, Fig. 5G). Finally, we examined the effect of GSK3 inhibitor XIII on the expression levels of Nav1.2 channels using Western blot analysis of total cell lysates. As illustrated in Fig. 5H–I, the Nav1.2 band intensity detected in cells treated with GSK3 inhibitor XIII (30 μM) did not differ from control (86% of control, n=7, p=0.61). From this data we inferred that GSK3 inhibition exerts an effect on Nav1.2 peak currents that is independent from mRNA translation mechanisms and does not affect total Nav1.2 protein expression level or protein stability.

Figure 5. GSK3 inhibition does not affect Nav1.2 total protein levels.

Confocal images of HEK-Nav1.2 showing immunolabeling with a PanNav α subunit antibody (A,B,D,E) and a TOPRO-3 nuclear counterstain (A,D). A and D show a visualization of Nav1.2 channels (red) with the nuclear portions stained (blue) for reference in representative cells treated with DMSO or GSK3 inhibitor XIII, respectively. Single channel images show PanNav intensity (B,E) with 3-dimensional contour plots showing the respective intensity (C, F). Scale bar, 4 μm. G. Summary bar graph representing PanNav pixel intensity in cells treated with GSK3 inhibitor XIII versus control; the two means are not statistically different (p=0.614). H. Western blot analysis of Nav1.2 protein levels from total cell lysate from HEK-Nav1.2 cells treated with either DMSO (left) or GSK3 inhibitor (GSK3i) XIII (right) and probed with a PanNav antibody; calnexin immunoreactivity (rabbit polyclonal antibody) is used as a loading control. The expression levels of Nav1.2 (normalized to calnexin) under GSK3 inhibition were comparable to DMSO control. I. Summary bar graph, treatment did not significantly alter Nav1.2 content in the cells. NS= statistically non-significant.

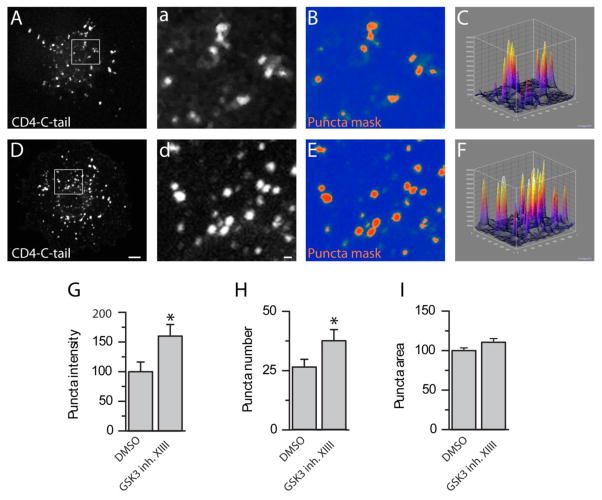

3.1.5 GSK3 controls surface expression level of Nav1.2 channels

Inhibition of GSK3 could lead to an up-regulation of Nav1.2-encoded currents by increasing the number of Nav1.2 channels on the cell surface. To test this hypothesis, we expressed chimeric constructs carrying the single transmembrane domain protein CD4, depleted of its intracellular C-terminal tail (CD4-ΔC-tail), fused in frame with either the I–II loop (CD4-Nav1.2-I-II loop), the II–III loop (CD4-Nav1.2-II-III loop), or the C-terminal tail of the Nav1.2 (CD4-Nav1.2-C-tail), intracellular domains of the Nav1.2 channel rich in trafficking motifs and phosphorylation sites [36–38]. These constructs were transiently expressed in COS-7 cells, and the CD4 surface pool was labeled using an Alexa 488-conjugated antibody against the extracellular domain of CD4 applied on live cells, followed by fixation and staining with HCS Cell Mask™ Deep Red Plasma membrane stain to label the cell contour (Fig. 6A–H). In agreement with previous results, we observed a notable difference in the expression pattern of different CD4 constructs; the CD4 control showed a diffuse pattern, while the CD4 constructs expressing the Nav1.2 intracellular domains exhibited various degrees of punctate staining. While there was no significant difference in the surface labeling pattern or intensity of CD4 ΔC-tail (96.3 ± 28.3 %, n=25 versus n=20 in control, p=0.3), CD4-Nav1.2-I-II loop (79.6 ± 15.8 %, n=29 versus n=10 in control, p=0.38), and the CD4-Nav1.2-II-III loop (120.53 ± 10.43 %, n=27 versus n=29 in control, p=0.08) in cells treated with GSK3 inhibitor XIII versus DMSO (Fig. 6), a significant increase in total fluorescence intensity was observed in the CD4-Nav1.2-C-tail group (148.81 ± 12.89, n=33 versus n=30 in control, p=0.002). Quantification of the total fluorescence intensity values representing the total surface pool of each construct in the two experimental conditions is shown in Fig. 6I. To more closely examine the observed phenotype on the CD4-Nav1.2-C-tail, we quantified the number of puncta per cell, their relative fluorescence intensity, and their size in the two experimental conditions. As illustrated in Fig. 7, there was a significant increase in the puncta fluorescence intensity (160 ± 19.46%, p=0.02, Fig. 7G), the puncta number per cell (n=39 versus n=26 in control, p=0.03, Fig. 7H), but not in the puncta size (110 ± 4.69, p=0.07, Fig. 7I) in the group treated with GSK3 inhibitor XIII (n=29 cells) versus DMSO (n=31 cells). These results indicate that GSK3 might control surface trafficking of Nav1.2 through an action on the C-terminal tail of the channel. This mechanism is likely to lead to the change in Nav1.2 peak current density that we detected with electrophysiological recordings (Fig. 1,2)

Figure 7. GSK3 inhibition alters the intensity and number of CD4-C-tail puncta.

Confocal images of COS-7 cells expressing the CD4-Nav1.2-Ctail with DMSO (A–C) or GSK3 Inhibitor XIII treatment (D–F). Grayscale images (A, D) show visualization of CD4-Nav1.2-Ctail puncta with an Alexa-488-conjugated anti-human CD4 antibody; lowercase letters show the boxed inset of their uppercase counterpart. A puncta mask shows the fluorescent intensity of the puncta in either group (B, E), and surface plots (C, F) show puncta intensity and distribution in three dimensions. Summary bar graph of the total fluorescent intensity of puncta (G), puncta number (H), and individual puncta area (I). A schematic representation of the chimeric constructs is shown in J. *(p<0.05). Scale bars: 4 μm (A,D) and 2 μm (a,d).

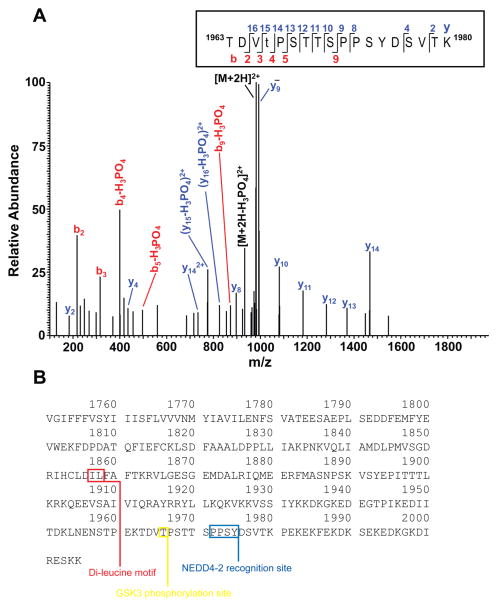

3.1.6 GSK3 phosphorylates Nav1.2 C-tail peptide at threonine1966

An in vitro phosphorylation experiment was performed with a synthetic peptide representing a portion of the Nav1.2 peptide encompassing T1966, a putative GSK3 phosphorylation site found phosphorylated in native Nav1.2 [36]. The reaction was digested with trypsin and analyzed by nanoLC-MS/MS. The resulting database search identified the doubly charged phosphopeptide of interest (theroretical [M+2H]+2 is m/z 981.933, observed m/z 981.935; mass error 2 ppm) eluting at approximately 28 minutes. Manual inspection of the high-resolution fragmentation spectrum (Figure 8) confirmed the proposed sequence and supported the assignment of T1966 as the site of phosphorylation. The base peak in the spectrum corresponds to unfragmented, doubly charged parent ion. Loss of phosphoric acid from the parent ([M+2H-H3PO4]2+) is seen at m/z 932.95 (theor. m/z 932.94), providing confirmation of phosphorylation. T1966 is determined to be the site of phosphorylation due to the presence of unphosphorylated b3 (theor. m/z 316.15, obs’d 316.15) and y14 (theor. m/z 1466.70, obs’d 1466.71) ions flanking the phosphosite. Although the phosphorylated b5 and y15 ions flanking the phosphosite were not seen, they were identified with loss of phosphoric acid. From the first two threonines (T) present in the sequence, we excluded the first as phosphorylated due to the presence of the b2 ion, which accounts for the combined unphosphorylated mass of threonine and aspartate (TD). All ions in the y series up to y14 do not demonstrate a loss of H3PO4, indicating that the serines (S) and threonines from amino acid 1968 to 1980 are not phosphorylated. Taken together, these ions confirm the sequence as shown and support phosphorylation of T1966. We note the phosphorylated T1966 is present at the beginning of a GSK3 consensus motif S/TXXXS/T within C-terminus of Nav1.2

Figure 8. GSK3β phosphorylates T1966.

A. Higher energy collisional dissociation (HCD) high resolution fragmentation spectrum of the phosphopeptide TDVtPSTTSPPSYDSVTK, encompassing residues 1961–1980 of the Nav1.2 sequence is shown in the boxed area. The presence of non-phosphorylated b3 (theoretical m/z of 316.15, observed m/z of 316.15) and y14 (theoretical m/z of 1466.70, observed m/z of 1466.71) ions confirms T1966 as the site of phosphorylation. (t = phosphothreonine). Due to the treatment with trypsin after the in vitro phosphorylation experiments, enzymatic cleavage occurred at lysine (K) 1962 removing the glutamate (E) and lysine at the N-terminus of the full-length peptide. B. C-terminal tail sequence of Nav1.2 (amino acids 1751–2005). The GSK3 phosphorylation site (T1966) is boxed in yellow, the di-leucine motif in red, and the NEDD4-2 recognition motif in blue.

4.1 Discussion and conclusions

In this study we provide evidence for a new role of GSK3 in regulating Nav1.2 channel function. Our results indicate that Nav1.2-encoded currents are significantly higher in amplitude in response to either pharmacological inhibition or genetic silencing of GSK3. Conversely, overexpression of GSK3β suppressed Nav1.2-mediated currents. This potentiation of Nav current is independent of mRNA translation or total protein levels, but involves trafficking of the channel to the plasma membrane. Surface labeling analysis of chimeric constructs expressing various intracellular domains of the Nav1.2 channel revealed that inhibition of GSK3 increases the Nav1.2 C-terminal tail surface level, but has no significant effects on other Nav1.2 intracellular domains. Importantly, in vitro phosphorylation combined with high resolution mass spectrometry identified T1966 as a phosphorylation site at the Nav1.2 C-terminal tail as a target site for GSK3β. Altogether, these results indicate a new mechanism of regulation of the GSK3 pathway on Nav1.2 channel function by controlling Nav1.2 current density, likely through modulation of the cell surface trafficking of the channel. Despite the fact that the vast majority of functionally relevant phosphorylation sites on Nav channels are identified at the I–II loop [7, 36, 39], our data indicate that GSK3 acts at the C-terminal tail. These results are in line with a central role of the C-terminal tail of the Nav channel in determining the channel kinetics [40], trafficking [30] and degradation [41] through post-translational modifications and protein:protein interactions [31, 42–44]. Furthermore, our results extend the layer of intracellular signaling cascades targeting the native Nav channel and neuronal excitability and provide a framework to understand the pathophysiology of Nav channelopathies [45], GSK3-related brain disorders [46], and psychiatric illnesses [47, 48].

Our electrophysiological studies indicate a pronounced increase of Nav1.2-encoded peak current densities upon GSK3 inhibitor XIII treatment following a short exposure time. The phenotype is reproduced upon genetic silencing of GSK3, clearly indicating that the GSK3 enzyme is required for the observed modulation. Although the mechanisms underlying this rapid and the more prolonged siRNA-dependent Na+ current potentiation are not known yet, the resulting phenotype is identical, indicating that GSK3 is part of both a short-term and long-term program that controls Nav1.2 function. Furthermore, overexpression of GSK3β results in suppression of Nav1.2 currents, providing evidence for bidirectional control of Nav1.2. Given its dynamic range, this GSK3-mediated modulation of Nav1.2 currents likely provides a means for controlling neuronal excitability in rapid and chronic homeostatic adaptations in the brain circuitry. Future investigations in animal models are warranted on this topic.

Our RT-PCR, quantitative immunofluorescence, and Western blot analyses concur in showing no changes in the Nav1.2 mRNA transcript and global protein expression level upon GSK3 inhibition. Notably, while our findings do not indicate a change in Nav channel mRNA, other studies have found that GSK3 inhibition can induce an upregulation in Nav1.7 α-subunit mRNA that drives changes in surface expression of the channel [26]. If the differences cannot be attributed to the cell background and environment, this may suggest two mechanisms by which GSK3 could regulate Nav channel function, one dependent and the other independent of mRNA-driven mechanisms. Alternatively, time-course may also factor in, as our pharmacological treatments were relatively acute, and thus over a much longer exposure time, mRNA may be affected. Overall, though, our findings imply that the total pool of Nav1.2 remains constant following the GSK3 inhibitor treatment, ruling out genetic modifications or degradation of the Nav1.2 channel as mechanisms underlying the Na+ current potentiation observed with electrophysiology.

If the total pool of protein is unchanged, then up-regulation of Na+ currents could result from change in trafficking to the plasma membrane. We tested this hypothesis using a series of CD4 chimeric constructs expressing the I–II loop, the II–III loop or the C-terminal tail of the Nav1.2 channel and examined their plasma membrane expression using cell surface labeling [30, 37]. Our results indicate that exposure to GSK3 inhibitor XIII induces an increase in cell surface expression of the construct carrying the Nav1.2 C-terminal tail, but not other intracellular Nav1.2 domains. A thorough quantification from confocal stacks revealed an increase in the number of CD4-Nav1.2-C-tail puncta upon GSK3 inhibition, a phenotype that can be reconciled with an up-regulated traffic of the protein to the cell surface. Considering the number of phosphorylation sites and trafficking motifs identified at the I–II [36] and II–III loop [18, 37, 49], this result is surprising. However, a closer inspection of the Nav1.2 channel sequence revealed a putative GSK3 consensus motif at T1966 in the C-terminal tail of Nav1.2 (S/TpXXXS/T and S/TpXXS/T) [50]. Recent mass spectrometry studies from native tissue have identified 15 phosphorylation sites in the Nav1.2 sequence, including T1966 [36]. Using in vitro phosphorylation combined with high resolution mass spectrometry, we demonstrate the phosphorylation of T1966 by GSK3β. The C-tail sequence with relevant sites and motifs highlighted is shown in Figure 8B.

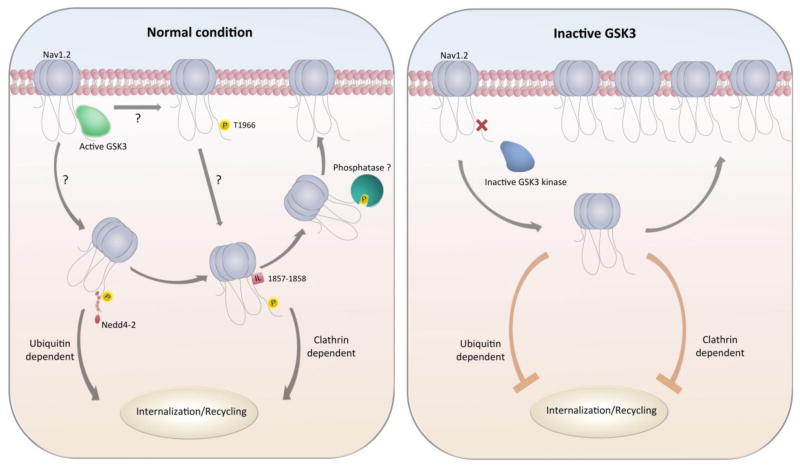

The molecular mechanism underlying the GSK3-dependent modulation of Na+ current remains to be determined, but it might be explained if GSK3 inhibitors prevent phosphorylation of site(s) that normally promote internalization from the membrane and recycling of the Nav1.2 protein. The E3 ubiquitin ligase family neural precursor cell expressed developmentally down-regulated protein 4 (NEDD4) has been shown to be involved in Nav1.2 internalization [38] and might be part of the GSK3-dependent mechanism described in this study. Co-expression of NEDD4 or NEDD4-2 significantly impairs Nav1.2 function, leading to suppression of Na+ currents. This effect is mediated via interactions with the PPxY recognition motif within the channel C-tail (Figure 8) and is reversed by mutating PPxY [41, 51]. Notably, this NEDD4-2-driven mechanism is conserved in other Nav channel isoforms [19] and it has been reported in KCNQ2/3 channels, where NEDD4-2 suppresses K+ currents [38]. Intriguingly, T1966 is proximal to the PPXY1975 motif. Thus, if phosphorylated by GSK3, T1966 might act as a “priming” site for NEDD4-2-mediated ubiquitination, promoting channel internalization and recycling [38, 52]. On the other hand, in its de-phosphorylated form, T1966 might limit or cease facilitating the NEDD4-2 interaction, stabilizing the Nav1.2 channel and increasing its cell surface expression (Figure 9). In addition to NEDD4-2-mediated changes in channel trafficking and distribution, the C-terminal tail of Nav1.2 also contains known double leucine motifs (Figure 8B) that are responsible for mediating clathrin-dependent endocytosis [30]. It is possible that preventing GSK3 from phosphorylating its target site could cause conformational or energetic changes that make clathrin-dependent endocytosis more difficult or impossible, leading to a build-up of Na+ channels in the membrane and thus potentiating current density. A working model for the hypotheses described is illustrated in Figure 9.

Figure 9. Working model of GSK3 regulation.

In native conditions, GSK3 phosphorylates the Nav1.2 C-tail at T1966 and may allow for internalization from the membrane through either a NEDD4-2 or a di-leucine recognition site. Upon GSK3 inhibition, lack in C-tail phosphorylation might prevent internalization resulting in an increased surface expression of Nav1.2.

Based on the fact that inhibition of GSK3 causes an up-regulation of Nav currents along with a change in surface expression, our current model is that phosphorylation of one site (or more sites) on the Nav1.2 channel by GSK3 exerts a suppressive effect in normal conditions. Emerging evidence suggests that lowered GSK3 activity can decrease Na+ currents and neuronal excitability, a finding that contradicts ours. Studies have shown that pharmacological inhibition of GSK3 with the compound AR-A014418 attenuates repeated firing and reduces Na+ currents in cultured neurons [53]. Differences in the cell background, the microenvironment, and in the set of protein:protein interactions in neurons versus HEK293 cells or regulatory effects of GSK3 specific to the isoform of Nav channel could all contribute to these variations and should be investigated in future studies.

The results presented here are the first report of a direct effect of the GSK3 pathway on Nav1.2-encoded currents, supporting the role of the Nav channel C-terminal tail as a critical component of the Nav channel function regulation. In the brain, this mechanism might contribute to an extreme fine-tuning of ion channel function and excitability at the base of channelopathies, GSK3-linked brain disorders, and psychiatric illnesses.

Highlights.

New, bidirectional control of Nav1.2-encoded currents by GSK3 inhibition and/or overexpression

Inhibition of GSK3 produces changes in surface expression of Nav1.2 carboxy-tail

GSK3β phosphorylates Nav1.2 at T1966

Functional link between GSK3 and Nav1.2 with implications for excitability and brain disorders

Acknowledgments

We thank Dingge Li, Elizabeth Crofton, and Yafang Zhang for help in preparing and analyzing RT-PCR experiments; Sanaalarab Al Enazy for illustrations. This work was supported by NIH/NIEHS-T32ES007254 (TJ), CPRIT-RM1122 (CLN), 1008900 (DL), 1005799 (DL), NHARP-003652-0136-2009 (DL), and NIH/NIMH 0955995 (FL).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Catterall WA, Raman IM, Robinson HP, Sejnowski TJ, Paulsen O. The Hodgkin-Huxley heritage: from channels to circuits. J Neurosci. 2012;32:14064–14073. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3403-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Waxman SG. Neuroscience: Channelopathies have many faces. Nature. 2011;472:173–174. doi: 10.1038/472173a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Catterall WA, Dib-Hajj S, Meisler MH, Pietrobon D. Inherited neuronal ion channelopathies: new windows on complex neurological diseases. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2008;28:11768–11777. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3901-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gasparini S, Magee JC. Phosphorylation-dependent differences in the activation properties of distal and proximal dendritic Na+ channels in rat CA1 hippocampal neurons. J Physiol. 2002;541:665–672. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.020503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Loftis JL, King DD, Colbert CM. Kinase-dependent loss of Na+ channel slow-inactivation in rat CA1 hippocampal pyramidal cell dendrites after brief exposure to convulsants. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;18:1029–1032. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02832.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Colbert CM, Johnston D. Protein kinase C activation decreases activity-dependent attenuation of dendritic Na+ current in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1998;79:491–495. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.1.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cantrell AR, Catterall WA. Neuromodulation of Na+ channels: an unexpected form of cellular plasticity. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:397–407. doi: 10.1038/35077553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scheuer T. Regulation of sodium channel activity by phosphorylation. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2011;22:160–165. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Numann R, Catterall WA, Scheuer T. Functional modulation of brain sodium channels by protein kinase C phosphorylation. Science. 1991;254:115–118. doi: 10.1126/science.1656525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li M, West JW, Numann R, Murphy BJ, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Convergent regulation of sodium channels by protein kinase C and cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Science. 1993;261:1439–1442. doi: 10.1126/science.8396273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li M, West JW, Lai Y, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Functional modulation of brain sodium channels by cAMP-dependent phosphorylation. Neuron. 1992;8:1151–1159. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90135-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.West JW, Numann R, Murphy BJ, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. A phosphorylation site in the Na+ channel required for modulation by protein kinase C. Science. 1991;254:866–868. doi: 10.1126/science.1658937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen Y, Yu FH, Sharp EM, Beacham D, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Functional properties and differential neuromodulation of Na(v)1.6 channels. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2008;38:607–615. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu C, Li Q, Su Y, Bao L. Prostaglandin E2 promotes Na1.8 trafficking via its intracellular RRR motif through the protein kinase A pathway. Traffic. 2010;11:405–417. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2009.01027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Persson AK, Gasser A, Black JA, Waxman SG. Nav1.7 accumulates and co-localizes with phosphorylated ERK1/2 within transected axons in early experimental neuromas. Exp Neurol. 2011;230:273–279. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wittmack EK, Rush AM, Hudmon A, Waxman SG, Dib-Hajj SD. Voltage-gated sodium channel Nav1.6 is modulated by p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. J Neurosci. 2005;25:6621–6630. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0541-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leterrier C, Brachet A, Fache MP, Dargent B. Voltage-gated sodium channel organization in neurons: protein interactions and trafficking pathways. Neuroscience letters. 2010;486:92–100. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.08.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brechet A, Fache MP, Brachet A, Ferracci G, Baude A, Irondelle M, Pereira S, Leterrier C, Dargent B. Protein kinase CK2 contributes to the organization of sodium channels in axonal membranes by regulating their interactions with ankyrin G. J Cell Biol. 2008;183:1101–1114. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200805169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gasser A, Cheng X, Gilmore ES, Tyrrell L, Waxman SG, Dib-Hajj SD. Two Nedd4-binding motifs underlie modulation of sodium channel Nav1.6 by p38 MAPK. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:26149–26161. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.098681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berendt FJ, Park KS, Trimmer JS. Multisite phosphorylation of voltage-gated sodium channel alpha subunits from rat brain. J Proteome Res. 2010;9:1976–1984. doi: 10.1021/pr901171q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wildburger NC, Laezza F. Control of neuronal ion channel function by glycogen synthase kinase-3: new prospective for an old kinase. Frontiers in molecular neuroscience. 2012;5:80. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2012.00080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jope RS, Roh MS. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK3) in psychiatric diseases and therapeutic interventions. Curr Drug Targets. 2006;7:1421–1434. doi: 10.2174/1389450110607011421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beaulieu JM, Gainetdinov RR, Caron MG. Akt/GSK3 signaling in the action of psychotropic drugs. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2009;49:327–347. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.011008.145634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crews L, Masliah E. Molecular mechanisms of neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:R12–20. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li X, Jope RS. Is glycogen synthase kinase-3 a central modulator in mood regulation? Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:2143–2154. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yanagita T, Maruta T, Nemoto T, Uezono Y, Matsuo K, Satoh S, Yoshikawa N, Kanai T, Kobayashi H, Wada A. Chronic lithium treatment up-regulates cell surface Na(V)1.7 sodium channels via inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3 in adrenal chromaffin cells: enhancement of Na(+) influx, Ca(2+) influx and catecholamine secretion after lithium withdrawal. Neuropharmacology. 2009;57:311–321. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yanagita T, Maruta T, Uezono Y, Satoh S, Yoshikawa N, Nemoto T, Kobayashi H, Wada A. Lithium inhibits function of voltage-dependent sodium channels and catecholamine secretion independent of glycogen synthase kinase-3 in adrenal chromaffin cells. Neuropharmacology. 2007;53:881–889. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2007.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Catterall WA, Goldin AL, Waxman SG. International Union of Pharmacology. XLVII. Nomenclature and structure-function relationships of voltage-gated sodium channels. Pharmacological reviews. 2005;57:397–409. doi: 10.1124/pr.57.4.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shavkunov AS, Wildburger NC, Nenov MN, James TF, Buzhdygan TP, Panova-Elektronova NI, Green TA, Veselenak RL, Bourne N, Laezza F. The fibroblast growth factor 14. voltage-gated sodium channel complex is a new target of glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3) The Journal of biological chemistry. 2013;288:19370–19385. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.445924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garrido JJ, Fernandes F, Giraud P, Mouret I, Pasqualini E, Fache MP, Jullien F, Dargent B. Identification of an axonal determinant in the C-terminus of the sodium channel Na(v)1.2. Embo J. 2001;20:5950–5961. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.21.5950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shavkunov AS, Wildburger NC, Nenov MN, James TF, Buzhdygan TP, Panova-Elektronova NI, Green TA, Veselenak RL, Bourne N, Laezza F. The Fibroblast Growth Factor 14:Voltage-gated Sodium Channel Complex Is a New Target of Glycogen Synthase Kinase 3 (GSK3) J Biol Chem. 2013;288:19370–19385. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.445924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Easley GR, Labate D, Colonna F. Shearlet based Total Variation for denoising. IEEE Trans Image Process. 2009;18:260–268. doi: 10.1109/TIP.2008.2008070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Easley GR, Labate D, Lim W. Sparse directional image representations using the discrete shearlet transform. Appl Comput Harmon Anal. 2008;25:25–46. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lindeberg T. Detecting Salient Blob-Like Image Structures and Their Scales with a Scale-Space Primal Sketch: A Method for Focus-of-Attention. International Journal of Computer Vision. 1993;11:283–318. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oberg AL, Vitek O. Statistical Design of Quantitative Mass Spectrometry-Based Proteomic Experiments. Journal of Proteome Research. 2009;8:12. doi: 10.1021/pr8010099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baek JH, Cerda O, Trimmer JS. Mass spectrometry-based phosphoproteomics reveals multisite phosphorylation on mammalian brain voltage-gated sodium and potassium channels. Seminars in cell & developmental biology. 2011;22:153–159. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2010.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Garrido JJ, Giraud P, Carlier E, Fernandes F, Moussif A, Fache MP, Debanne D, Dargent B. A targeting motif involved in sodium channel clustering at the axonal initial segment. Science. 2003;300:2091–2094. doi: 10.1126/science.1085167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bongiorno D, Schuetz F, Poronnik P, Adams DJ. Regulation of voltage-gated ion channels in excitable cells by the ubiquitin ligases Nedd4 and Nedd4-2. Channels (Austin) 2011;5:79–88. doi: 10.4161/chan.5.1.13967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cantrell AR, Tibbs VC, Yu FH, Murphy BJ, Sharp EM, Qu Y, Catterall WA, Scheuer T. Molecular mechanism of convergent regulation of brain Na(+) channels by protein kinase C and protein kinase A anchored to AKAP-15. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2002;21:63–80. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2002.1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reddy Chichili VP, Xiao Y, Seetharaman J, Cummins TR, Sivaraman J. Structural basis for the modulation of the neuronal voltage-gated sodium channel NaV1.6 by calmodulin. Sci Rep. 2013;3:2435. doi: 10.1038/srep02435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fotia AB, Ekberg J, Adams DJ, Cook DI, Poronnik P, Kumar S. Regulation of neuronal voltage-gated sodium channels by the ubiquitin-protein ligases Nedd4 and Nedd4-2. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:28930–28935. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402820200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lou JY, Laezza F, Gerber BR, Xiao M, Yamada KA, Hartmann H, Craig AM, Nerbonne JM, Ornitz DM. Fibroblast Growth Factor 14 is an Intracellular Modulator of Voltage-Gated Sodium Channels. J Physiol. 2005;569:179–193. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.097220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Laezza F, Gerber BR, Lou JY, Kozel MA, Hartman H, Craig AM, Ornitz DM, Nerbonne JM. The FGF14(F145S) mutation disrupts the interaction of FGF14 with voltage-gated Na+ channels and impairs neuronal excitability. J Neurosci. 2007;27:12033–12044. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2282-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shavkunov A, Panova N, Prasai A, Veselenak R, Bourne N, Stoilova-McPhie S, Laezza F. Bioluminescence methodology for the detection of protein-protein interactions within the voltage-gated sodium channel macromolecular complex. Assay and drug development technologies. 2012;10:148–160. doi: 10.1089/adt.2011.413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kullmann DM, Waxman SG. Neurological channelopathies: new insights into disease mechanisms and ion channel function. J Physiol. 2010;588:1823–1827. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.190652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jope RS. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 in the etiology and treatment of mood disorders. Frontiers in molecular neuroscience. 2011;4:16. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2011.00016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dickinson D, Straub RE, Trampush JW, Gao Y, Feng N, Xie B, Shin JH, Lim HK, Ursini G, Bigos KL, Kolachana B, Hashimoto R, Takeda M, Baum GL, Rujescu D, Callicott JH, Hyde TM, Berman KF, Kleinman JE, Weinberger DR. Differential effects of common variants in SCN2A on general cognitive ability, brain physiology, and messenger RNA expression in schizophrenia cases and control individuals. JAMA psychiatry. 2014;71:647–656. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hsu WC, Nilsson CL, Laezza F. Role of the axonal initial segment in psychiatric disorders: function, dysfunction, and intervention. Frontiers in psychiatry. 2014;5:109. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2014.00109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Van Wart A, Boiko T, Trimmer JS, Matthews G. Novel clustering of sodium channel Na(v)1.1 with ankyrin-G and neurofascin at discrete sites in the inner plexiform layer of the retina. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2005;28:661–673. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2004.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Farghaian H, Turnley AM, Sutherland C, Cole AR. Bioinformatic prediction and confirmation of beta-adducin as a novel substrate of glycogen synthase kinase 3. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:25274–25283. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.251629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rougier JS, van Bemmelen MX, Bruce MC, Jespersen T, Gavillet B, Apotheloz F, Cordonier S, Staub O, Rotin D, Abriel H. Molecular determinants of voltage-gated sodium channel regulation by the Nedd4/Nedd4-like proteins. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2005;288:C692–701. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00460.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cusdin FS, Clare JJ, Jackson AP. Trafficking and cellular distribution of voltage-gated sodium channels. Traffic. 2008;9:17–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2007.00673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sanchez-Ponce D, Tapia M, Munoz A, Garrido JJ. New role of IKK alpha/beta phosphorylated I kappa B alpha in axon outgrowth and axon initial segment development. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2008;37:832–844. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2008.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]