Abstract

Objectives

We sought to determine the prognostic significance of extralobar nodal metastases versus intralobar nodal metastases in patients with lung cancer and pathologic stage N1 disease.

Methods

A retrospective review of a prospectively maintained lung resection database identified 230 patients with pathologic stage II, N1 non–small cell lung cancer from 1997 to 2011. The surgical pathology reports were reviewed to identify the involved N1 stations. The outcome variables included recurrence and death. Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed using the R statistical software package.

Results

A total of 122 patients had extralobar nodal metastases (level 10 or 11); 108 patients were identified with intralobar nodal disease (levels 12–14). The median follow-up was 111 months. The baseline characteristics were similar in both groups. No significant differences were noted in the surgical approach, anatomic resections performed, or adjuvant therapy rates between the 2 groups. Overall, 80 patients developed recurrence during follow-up: 33 (30%) of 108 in the intralobar and 47 (38%) of 122 in the extralobar cohort. The median overall survival was 46.9 months for the intralobar cohort and 24.4 months for the extralobar cohort (P<.001). In a multivariate Cox proportional hazard model that included the presence of extralobar nodal disease, age, tumor size, tumor histologic type, and number of positive lymph nodes, extralobar nodal disease independently predicted both recurrence-free and overall survival (hazard ratio, 1.96; 95% confidence interval, 1.36–2.81; P = .001).

Conclusions

In patients who underwent surgical resection for stage II non–small cell lung cancer, the presence of extralobar nodal metastases at level 10 or 11 predicted significantly poorer outcomes than did nodal metastases at stations 12 to 14. This finding has prognostic importance and implications for adjuvant therapy and surveillance strategies for patients within the heterogeneous stage II (N1) category.

In the evaluation and management of non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), accurate staging is critical for appropriate medical and surgical management. The identification of nodal metastases has formed the basis for prognostic stratification in patients eligible for resection. The presence of N1 nodal metastasis will reduce the 5-year survival from 56% to 38% compared with node-negative disease.1

The N1 classification is anatomically heterogeneous, including the hilar (level 10), interlobar (level 11), lobar (level 12), and segmental and subsegmental (level 13 and 14) nodes.2 Given this anatomic heterogeneity, a number of studies have sought to investigate further the anatomic stations within the N1 classification in the hopes of refining the nodal staging schema for better prognostic stratification.3–11 Many of these studies have identified trends toward worse outcomes with more anatomically central nodal involvement; however, the data have remained inconclusive. Most of these studies have included patients with advanced (T3-T4) primary tumors and N1 disease. This has likely obscured some of the prognostic effects of the nodal metastases, because the effect of N1 disease has been shown to dissipate with advanced T stages.4,5

The most recent of these studies analyzed 522 patients with stage N1 disease of the 2876 evaluable patients in the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer Staging Project for Lung Cancer.1 Although that analysis was not sufficient to change the N1 staging system, a trend was seen toward decreased survival with positive level 10 nodes in contrast to positive level 12 nodes. Because only 380 of the patients were from North America, positron emission tomography was not used, and surgical therapy was not standardized, we sought to perform a similar analysis using our single-institution database. In addition, we examined the effect of anatomic nodal station on survival within the N1 classification by focusing on patients with stage II, T1-T2N1, minimizing the confounding effects of T stage on the outcome.

METHODS

Reviewing the medical records of 1000 consecutive patients undergoing lung resection at Duke University Medical Center from 1997 to 2011, we identified 230 patients with stage II pN1 NSCLC (T1 and T2 tumors). Clinical information was obtained from a review of the electronic medical records after the institutional review board approved the study. All patients had undergone surgery at Duke University Hospital with lung resection and mediastinal lymphadenectomy. The surgical pathology reports were reviewed and the lymph node stations categorized according to the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer TNM staging system, with the lymph node levels identified as described by Mountain and Dresler.2 Metastases to level N1 nodes and the lack of disease to N2 nodes were confirmed in each surgical pathology report. Extralobar lymph node stations were defined as those removed separately and identified as level 10 or 11 and those nodes identified by the pathologist as “hilar.” The pathologists uniformly used this designation when the lymph node was clearly extraparenchymal. Intralobar nodal stations included nodes removed and identified as level 12 and those identified within the specimen as “parenchymal.” We defined our “intralobar” group as patients with disease limited to stations 12 to 14 and our “extralobar” group as patients with disease at level 10 or 11, independent of the presence or absence of more peripheral nodal disease. We also performed a separate analysis in which the patients with both intralobar and extralobar disease were considered as a separate group. The follow-up period for the group ranged from 0 to 133 months (mean, 111). Information was gathered on the number of examined nodes and the number positive at each nodal station. Additional clinical information was obtained regarding the use of adjuvant chemotherapy and outcomes, including the timing and site of recurrences and death. The Social Security Death Index was also queried to maximize the information on overall survival.

Statistical Analysis

Comparisons between patient and treatment variables were made and evaluated using Student t test, Fisher exact test, or chi-square tests, as appropriate. Survival was calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method, with between-group comparisons made using the log-rank test. Multivariate analysis was conducted using a Cox proportional hazards model. Statistical analysis was performed using the R statistical software package (Free Software Foundation, Inc, Boston, Mass).

RESULTS

Of the 230 identified patients with stage II, pathologic N1 disease, 122 were identified with extralobar disease at stations 10 and 11 and 108 as having lymph node metastases confined to intralobar stations 12 to 14. Within the extralobar group, a few (n = 26) had additional peripheral nodal metastases at the intralobar stations, but most (n= 96) had nodal disease confined to the extralobar stations. The baseline patient characteristics are listed in Table 1. No significant differences between the 2 groups were noted in age or pulmonary function as measured by the diffusion capacity. Small, but statistically significant, differences were noted in the forced vital capacity and primary tumor size, leading to the latter’s inclusion in the multivariate survival model.

TABLE 1.

Patient and clinical characteristics

| Characteristic | Extralobar positive | Intralobar positive | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (y) | 63.3 | 65.8 | .07 |

| Mean FEV1 (% predicted) | 68.6 | 75.2 | .007 |

| Mean DLCO (% predicted) | 74.9 | 75.1 | .98 |

| Mean size (cm) | 3.16 | 3.54 | .05 |

| VATS approach (%) | 38.9 | 45.9 | .29 |

| Lobectomy (%) | 75.0 | 71.3 | .63 |

| Adjuvant therapy (%) | 44.3 | 44.4 | .92 |

| Histologic type (%) | .003 | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | 46 | 37 | |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 30 | 50 |

FEV1, Forced expiratory volume in 1 second; DLCO, diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide; VATS, video-assisted thoracic surgery.

The lymph node yield ranged from 1 to 26 nodes (mean, 6 recovered per patient). The positive lymph node rates ranged from 1 to 12 (mean, 1.83 positive per patient). Lobectomy was the most common surgical resection procedure, performed in 168 (73%), followed by pneumonectomy in 41 (18%). Bilobectomy (n = 14, 6.1%) and segmentectomy (n = 7, 3%) were performed in a few patients. Thoracotomy was the primary surgical approach overall, used in 132 patients (57%). As expected, the surgical approach evolved over time. Before 2003, thoracotomy was used in 82% of the resections; after 2003, thoracoscopy became the dominant approach. It was used in 58% of patients, a percentage that stayed relatively stable through the end of the study period.

Primary tumors were assessed for location, size, histologic type, and grade. Right-sided lesions were slightly more common (53%), with right upper lobe tumors predominating (73%). Upper lobe tumors were also more common on the left side (68%). All tumors were stage T1 or T2, with most (73%) being T2 lesions. Overall, the mean tumor size was 3.3 cm. Adenocarcinoma (42%) and squamous cell carcinoma (40%) were the dominant histologic types. The tumors were graded as moderately differentiated in 36%, poorly differentiated in 34%, and well-differentiated in 5%.

Adjuvant chemotherapy was administered to 102 patients (44%). As expected, its use increased over time, with the application of adjuvant therapy increasing to 57% after 2007, despite all patients being referred for consideration of adjuvant treatment.

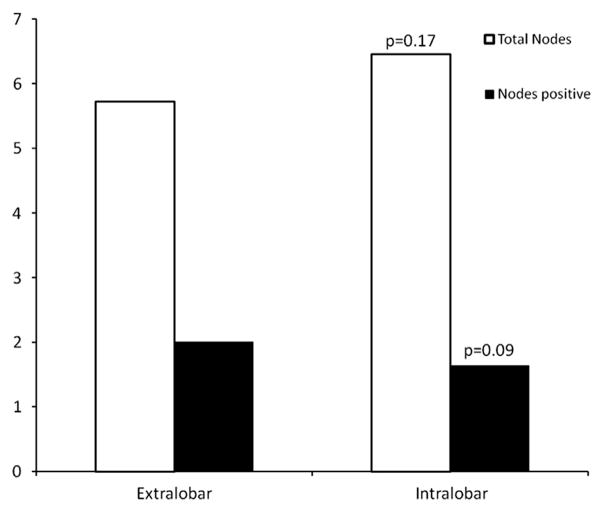

The 2 groups were examined along multiple clinical variables (Table 1). No statistically significant difference was noted in the frequency of a thoracoscopic approach, frequency of the various anatomic resections, or use of adjuvant chemotherapy. The total lymph node yield and number of positive lymph nodes have both been demonstrated to predict survival.15 No significant differences were identified in the total nodal yield or total number of positive nodes (Figure 1). However, a significant difference was seen in the histologic distribution of the tumors. Adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma remained the dominant histologic types in both groups; however, adenocarcinoma occurred with greater frequency in the extralobar metastasis group (46%vs 37%, P = .003), with squamous cell carcinoma constituting a correspondingly lower percentage (30% vs 50%, P < .001; Table 1).

FIGURE 1.

Comparison of total nodal harvest and positive node yield stratified by nodal station. No significant difference in the mean lymph node yield (P = .17) or mean number of positive nodes (P = .09) was detected between the extralobar and intralobar disease groups.

Cancer Recurrence

Cancer recurrence occurred in 80 of the 230 patients. Sixty percent of the recurrences occurred within the thorax, although few (12%) of those were truly at the site of previous resection. The remainder (48%) of intrathoracic metastases included multifocal mediastinal adenopathy or diffuse or contralateral parenchymal lesions. The remaining metastases were distributed evenly among the skeletal, brain, and abdominal lesions, with each comprising approximately 12% of the cases.

Of the recurrences, 47 were observed among patients with extralobar nodal disease (38%), and 33 were within the intralobar cohort (30%). Additional factors, including adjuvant chemotherapy, histologic type, surgical approach, and anatomic resection, were assessed for their effect on recurrence development (Table 2). No statistically significant differences were noted in the recurrence rates, although adenocarcinoma showed a trend toward a greater incidence of recurrence than squamous cell carcinoma (P = .07). Although the absolute recurrence rate was not significantly different statistically according to the nodal station on multivariate Cox model analysis, taking into account the interval to recurrence, the presence of extralobar nodal disease was a statistically significant predictor of disease recurrence (hazard ratio, 1.83; 95% confidence interval, 1.14–2.92; P = .011).

TABLE 2.

Clinical variables and cancer recurrence

| Characteristic | Recurrence rate (%) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Nodal disease | .21 | |

| Extralobar | 38.5 | |

| Intralobar | 30.6 | |

| Adjuvant therapy | .39 | |

| Yes | 36.3 | |

| No | 33.6 | |

| Surgical approach | .77 | |

| VATS | 40.0 | |

| Thoracotomy | 31.1 | |

| Resection extent | .21 | |

| Lobectomy | 37.5 | |

| Pneumonectomy | 27.0 | |

| Histologic type | .07 | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 43.2 | |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 30 |

VATS, Video-assisted thoracic surgery.

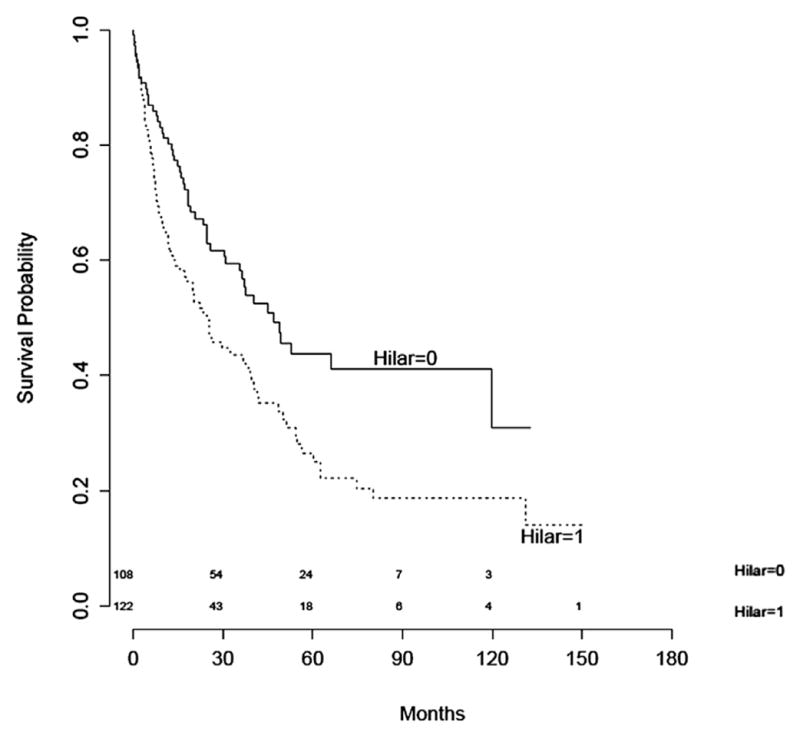

Survival

Of the 230 patients, 137 died. Seven patients (3%) died in the immediate perioperative period and were included in the calculations. Survival was calculated for patients according to the level of nodal involvement. Kaplan-Meier analysis (Figure 2) demonstrated a statistically significant difference in survival between patients with extralobar nodal disease and intralobar nodal disease (P = .003). Multivariate models of disease-free and overall survival were constructed. The presence of extralobar nodal metastases at level 10 or 11 predicted a poorer outcome (hazard ratio, 2.02; 95% confidence interval, 1.40–2.91; P = .0001; Table 3). The median overall survival was 46.9 months for the intralobar cohort and 24.4 months for the extralobar cohort. The 26 patients with both intralobar and extralobar nodal disease fared the same as the patients with extralobar disease alone.

FIGURE 2.

Kaplan-Meier overall survival curves for patients with stage II disease and extralobar (hilar = 1, level 10 or 11 positive) or intralobar (hilar = 0, levels 12–14 positive) nodal metastases. Log-rank test, P = .003.

TABLE 3.

Cox proportional hazard models

| Factor | HR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Disease-free survival | ||

| Extralobar positive | 1.83 (1.14–2.92) | .01 |

| Age (per y) | 1.02 (0.99–1.04) | .23 |

| Tumor size | 1.21 (1.03–1.42) | .02 |

| Number of positive nodes | 0.92 (0.767–1.09) | .34 |

| Squamous cell histologic type | 0.49 (0.289–0.823) | .007 |

| Overall survival | ||

| Extralobar positive | 2.02 (1.40–2.91) | .0001 |

| Age (per y) | 1.03 (1.01–1.05) | .001 |

| Tumor size | 1.10 (0.971–1.24) | .14 |

| Number of positive nodes | 0.87 (0.750–1.00) | .053 |

| Squamous cell histologic type | 0.70 (0.469–1.05) | .08 |

CI, Confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

DISCUSSION

Thorough lymph node staging at anatomic resection has become the standard of care for surgically managed NSCLC. The presence of N1 nodal metastases will have a significant effect on the prognosis, reducing the 5-year survival by one third.1 In addition, the identification of N1 nodal metastases has therapeutic ramifications, because patients with resected stage II NSCLC will benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy.12 The current National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines have recommended 4 cycles of a platinum-based doublet for all patients with resected N1-positive NSCLC.13 Within the N1 classification, however, the anatomic differences in nodal station are significant. Level 10 hilar nodes abut the pleural reflection and are in close proximity to the N2 mediastinal nodal basins,14 and level 13 to 14 nodes are peripherally encased within the parenchyma and can only be removed entirely during anatomic lung resection.

Thus, multiple groups during the past 2 decades have sought to reevaluate the N1 classification in an effort to further parse survival into more accurate substrata. The results have been mixed. Marra and colleagues5 and Caldarella and colleagues3 found statistically significant reductions in 5-year survival with extralobar nodal disease, and Maeshima and colleagues,6 Demir and colleagues,4 and Rusch and colleagues1 failed to find outcomes that reached statistical significance. However, these latter studies demonstrated a trend toward worse survival with extralobar disease. Although not a universal finding, multiple groups have also demonstrated that multistation disease results in a worse prognosis than single-station or single-node disease.1,4

One of the more significant investigations of the N1 nodal subgroups occurred in 2007, when the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer undertook revision of the TNM staging system for its seventh edition.1 In that study, nodal disease was described by zone, with peripheral intralobar stations 12 to 14 separated from the “hilar” or extralobar stations 10 and 11. Comparisons were made between single- and multiple-zone lesions. Although none reached statistical significance, a clinically important trend was observed, with “hilar” zone lesions demonstrating worse median survival than peripheral zone lesions (P = .059). These results were insufficient to justify a change to the N1 designation within the TNM staging system.

In the present study, we used the same zone designations, defined anatomically as extralobar (level 10 and 11) and intralobar (levels 12–14) disease. Unlike the previously cited studies, we have isolated the analysis to patients with stage II to avoid potential confounding effects from advanced T stage. Although some investigators have found no effect of T stage in the presence of N1 disease, others have found that T3 and T4 tumors eliminated the effect of lobar versus hilar nodal disease on survival. Although these latter studies found a survival advantage for lobar versus hilar disease only in patients with stage II disease, the outcomes of T3N1 and T4N1 disease were primarily determined by the completeness of the resection.4,6 In keeping with our hypothesis that extralobar disease is a more powerful predictor of the outcome, our extralobar designation was also defined by the highest level of nodal disease and thus included 26 patients with both extra- and intralobar disease. Importantly, we found no significant differences in patient factors or the number of lymph nodes harvested or positive, both factors found to affect the outcome.15 We found no significant differences in the modes of surgical therapy or approach. On multivariate analysis, we found significant differences in the disease-free and overall survival using the extralobar anatomic division.

In addition, a statistically significant difference was noted in the histologic type of the tumors between nodal groups, with a greater percentage of adenocarcinoma in the extralobar nodal metastasis category. Adenocarcinoma showed a trend toward greater recurrence rates compared with squamous cell carcinoma. On multivariate analysis, however, squamous cell carcinoma demonstrated a significant protective effect on survival compared with other histologic types. Although this finding is not novel,5 the prevailing belief has been that the histologic type does not have a significant differential effect on survival. The inclusion of both factors in our multivariate Cox proportional hazards model showed that the effect of the histologic type on survival did not eliminate the effect of the presence of extralobar nodal disease (Table 3). We found no effect of adjuvant therapy on recurrence; however, our data on the use of adjuvant therapy was hampered by the retrospective nature of our review and the limited data available on the specifics of treatment. Thus, our data were inadequate to effectively assess the effect of adjuvant therapy.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that, among patients with surgically resected stage II NSCLC with N1 disease, the presence of extralobar nodal metastases at levels 10 and 11 confers a poorer prognosis than does nodal disease confined to intralobar nodes. This finding underscores the importance of thorough and accurate hilar lymph node dissection during lung resection. It has been our institutional practice to remove and identify levels 10 and 11 separately for accurate staging. As a single-institution retrospective review, our study had the limitations of its retrospective nature, limited sample size, and statistical power. Nevertheless, our findings have potential therapeutic and prognostic significance. Despite the recommendations for adjuvant platinum-based chemotherapy, many patients will not receive this therapy for a variety of reasons.16,17 Identifying a subset of N1-positive patients at greater risk of recurrence would help strengthen the recommendations and support a more aggressive adjuvant treatment strategy for this population. Furthermore, patients with extralobar disease could be considered for trials of novel or additional adjuvant therapies.

Abbreviation and Acronym

- NSCLC

non–small cell lung cancer

Footnotes

Read at the 39th Annual Meeting of The Western Thoracic Surgical Association, Coeur d’Alene, Idaho, June 26–29, 2013.

Disclosures: Thomas D’Amico reports consulting fees from Scanlan. Betty Tong reports consulting fees from Covidien. Mark Onaitis reports consulting fees from Intuitive Surgical. All other authors have nothing to disclose with regard to commercial support.

References

- 1.Rusch VW, Crowley J, Giroux DJ, Goldstraw P, Im JG, Tsuboi M, et al. The IASLC lung cancer staging project: proposals for the revision of the N descriptors in the forthcoming seventh edition of the TNM classification for lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2007;2:603–12. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31807ec803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mountain CF, Dresler CM. Regional lymph node classification for lung cancer staging. Chest. 1997;111:1718–23. doi: 10.1378/chest.111.6.1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caldarella A, Crocetti E, Comin CE, Janni A, Pegna AL, Paci E. Prognostic variability among nonsmall cell lung cancer patients with pathologic N1 lymph node involvement: epidemiological figures with strong clinical implications. Cancer. 2006;107:793–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Demir A, Turna A, Kocaturk C, Gunluoglu MZ, Aydogmus U, Urer N, et al. Prognostic significance of surgical-pathologic N1 lymph node involvement in non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;87:1014–22. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.12.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marra A, Hillejan L, Zaboura G, Fujimoto T, Greschuchna D, Stamatis G. Pathologic N1 non-small cell lung cancer: correlation between patterns of lymphatic spread and prognosis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2003;125:543–53. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2003.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maeshima AM, Tsuta K, Asamura H, Tsuda H. Prognostic implication of metastasis limited to segmental (level 13) and/or subsegmental (level 14) lymph nodes in patients with surgically resected non-small cell lung carcinoma and pathologic N1 lymph node status. Cancer. 2012;118:4512–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miyoshi K, Mimura T, Iwanaga K, Adachi S, Tsubota N, Okada M. Surgical treatment of clinical N1 non-small cell lung cancer: ongoing controversy over diagnosis and prognosis. Surg Today. 2010;40:428–32. doi: 10.1007/s00595-008-4072-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Osaki T, Nagashima A, Yoshimatsu T, Tashima Y, Yasumoto K. Survival and characteristics of lymph node involvement in patients with N1 non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2004;43:151–7. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2003.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Riquet M, Manac’h D, Le Pimpec-Barthes F, Dujon A, Chehab A. Prognostic significance of surgical-pathologic N1 disease in non-small cell carcinoma of the lung. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999;67:1572–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tanaka F, Yanagihara K, Otake Y, Yamada T, Shoji T, Miyahara R, et al. Prognostic factors in patients with resected pathologic (p-) T1-2N1M0 non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2001;19:555–61. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(01)00670-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yano T, Yokoyama H, Inoue T, Asoh H, Tayama K, Ichinose Y. Surgical results and prognostic factors of pathologic N1 disease in non-small-cell carcinoma of the lung: significance of N1 level: lobar or hilar nodes. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1994;107:1398–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Winton T, Livingston R, Johnson D, Rigas J, Johnston M, Butts C, et al. Vinorelbine plus cisplatin vs. observation in resected non-small lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2589–97. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ettinger DS, Akerley W, Borghaei H, Chang AC, Cheney RT, Chirieac LR, et al. Non-small cell lung cancer, version 2.2013. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2013;11:645–53. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2013.0084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Asamura H, Suzuki K, Kondo H, Tsuchiya R. Where is the boundary between N1 and N2 stations in lung cancer? Ann Thorac Surg. 2000;70:1839–46. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(00)01817-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jonnalagadda S, Smith C, Mhango G, Wisnivesky JP. The number of lymph node metastases as a prognostic factor in patients with N1 non-small cell lung cancer. Chest. 2011;140:433–40. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-2885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kankesan J, Shepherd FA, Peng Y, Darling G, Li G, Kong W, et al. Factors associated with referral to medical oncology and subsequent use of adjuvant chemotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer: a population-based study. Curr Oncol. 2013;20:30–7. doi: 10.3747/co.20.1178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Booth CM, Shepherd FA, Peng Y, Darling G, Li G, Kong W, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy for non-small cell lung cancer: practice patterns and outcomes in the general population of Ontario, Canada. J Thorac Oncol. 2012;7:559–66. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31823f43af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]