Abstract

To evaluate the contributions of common noise sources to total annual noise exposures among urban residents and workers, we estimated exposures associated with five common sources (use of mass transit, occupational and non-occupational activities, MP3 player and stereo use, and time at home and doing other miscellaneous activities) among a sample of over 4500 individuals in New York City (NYC). We then evaluated the contributions of each source to total noise exposure and also compared our estimated exposures to the recommended 70 dBA annual exposure limit. We found that one in ten transit users had noise exposures in excess of the recommended exposure limit from their transit use alone. When we estimated total annual exposures, 90% of NYC transit users and 87% of nonusers exceeded the recommended limit. MP3 player and stereo use, which represented a small fraction of the total annual hours for each subject on average, was the primary source of exposure among the majority of urban dwellers we evaluated. Our results suggest that the vast majority of urban mass transit riders may be at risk of permanent, irreversible noise-induced hearing loss and that, for many individuals, this risk is driven primarily by exposures other than occupational noise.

INTRODUCTION

With the continued global trend toward urbanization,1 management of the growth of cities—and the daily transport of people into and out of those cities—is an increasingly complex and important concern. The challenges of efficiently moving large numbers of people have traditionally been addressed through mass transit infrastructure, and most major cities in the developed world have extensive transit systems. While some of these systems are more than 100 years old, nearly 10% of the 178 existing systems opened between 2006 and 2011.2 The benefits of these systems include improvements in air and water quality, increased speed of passenger movement, energy conservation, mitigation of climate change, and reductions in acute and chronic illness.3,4 In addition to moving large numbers of people efficiently and inexpensively, transit systems generally have excellent safety records, particularly when compared to automobiles.4

Despite these benefits, however, mass transit systems can also present public health hazards when not designed or maintained properly. For example, a public health hazard was recently declared for a new system in North America due to excessive noise levels.5 Noise exposure and subsequent noise-induced hearing loss (NIHL)—an irreversible disease with devastating personal and social ramifications—are common in developed and developing countries. As with most environmental exposures, the risk of NIHL from noise exposure depends on both the intensity and duration of exposure.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)6 and the World Health Organization (WHO)7 have recommended a noise exposure limit of 70 A-weighted decibels (dBA) for a 24 h equivalent continuous average level (Leq(24)). This limit incorporates all potential sources of noise exposure (e.g., commuting, occupational activities, etc.) and is designed to protect against any measurable NIHL in any exposed individual. Exposures in excess of this limit will result in NIHL in a fraction of the population. Increasing exposures above this limit result in a larger fraction of the population affected and a greater degree of NIHL in affected individuals. In addition to NIHL, noise exposure is increasingly being linked to nonauditory health effects such as coronary heart disease8 and hypertension9 (although the precise relationship between noise exposure and these health effects is not yet understood) and to other problems such as sleep disturbance, perceived stress, and reduced quality of life.10,11 These nonauditory effects of noise can occur at Leq(24) levels well below 70 dBA.12–14

Several studies have demonstrated transit noise levels that create a potential for daily exposure in excess of 70 dBA given sufficient transit use time.15–17 However, while these studies demonstrate the potential for overexposure, no previous studies appear to have estimated annual noise exposures for transit users, which account for both noise levels and transit use durations. As a result, it is difficult to draw conclusions regarding the risk of NIHL associated with transit-related noise exposure or the need for noise reduction efforts.

The current study had two goals. The first was to estimate annual noise exposures resulting from five different sources of noise for a sample of individuals who lived and/or worked in New York City (NYC). The sources were occupational and nonoccupational activities, listening to music, time spent at home, and, of primary importance for this study, use of mass transit. We selected NYC because it has the largest transit system in the United States18 and has by far the highest fraction of transit users of any U.S. city.19 The system spans the greater metropolitan NYC area and encompasses subways, commuter railroads, buses, and ferries. The various NYC area transit agencies reported over 8 million passenger rides each weekday in 2010.20 The second goal of our study was to estimate total annual exposures to determine the relative contributions of the five exposure sources. By comparing the source-specific and total estimates of annual exposure to the 70 dBA recommended exposure limit, the fraction of individuals in our sample at potential risk of NIHL could be determined.

METHODS

We utilized three data sources to conduct this study. The first source, which provided individual-level exposure duration information, was a self-reported survey. The second source, which provided noise levels associated with NYC transit, was our previously published transit noise analysis.15 The third source, which provided noise levels from nontransit noise sources, was the results of a search of peer-reviewed literature. All study procedures were approved by the Columbia University Institutional Review Board.

Data Collection

Surveys

We collected survey data using a modified street intercept methodology. Briefly, we recruited subjects by setting up a booth at 33 neighborhood street fairs in 2008 and 2009 in the NYC boroughs of Manhattan, Brooklyn, Queens, and the Bronx. Individuals who approached the booth were informed that our data collection effort was for a study on urban noise and also told of our eligibility criteria: age >18 years, ability to complete a self-administered survey in English or Spanish, and residence or employment in NYC. The incentive to participate was a $1 lottery ticket. Assenting individuals completed our anonymous survey, which consisted of 41 items written at a sixth-grade level (Flesch–Kincaid score)21 and took 10–15 min to complete. Survey items addressed were birth year, status as resident or employed in NYC, borough of residence, gender, usual ride and wait times on transit (bus, rail, ferry) as minutes per day and days per week, employment details, including work time as hours per week and weeks per year, time spent in five nonoccupational activities (playing in a band, attending sporting events, attending concerts, using lawn and power tools, and riding a motorcycle) as hours per month, time spent listening to MP3 players and stereos (referred to subsequently as MP3 player use) as hours per day, and use of hearing protectors at work, on transit, and during nonoccupational activities.

Assessment of Transit Noise Levels

Transit noise levels used for this study came from our data set of 239 LEQ dosimetry measurements made in 2007 on NYC rail (including subways and commuter rail), bus lines, and ferries.15 We supplemented these 2007 data with additional measurements made in 2009 using the same protocol and equipment. These measurements simulated 30–40 min long “commutes” on one or more types of transit designed to allow us to evaluate the accuracy of predicted transit exposures against measured levels.

Assessment of Occupational and Nonoccupational Noise Levels

To estimate exposures to the four nontransit sources of noise considered here (occupational and nonoccupational activities, MP3 player use, and time spent at home and doing other miscellaneous activities), we reviewed the peer-reviewed scientific literature. Our search was conducted for the interval 1990–2010 via www.pubmed.gov (accessed Dec 27, 2010) using the term “noise exposure level”. We identified 163 relevant papers and included 54 which used appropriate measurement methodologies and reported LEQ levels. For each source, we used up to six papers with the largest sample sizes and most robust methodologies. Where fewer than six papers were available, assigned values were based on a smaller number of papers. Using the reported LEQ levels in these papers, we computed arithmetic mean LEQ levels for each of the four sources (Supporting Information, Table S1).

Data Analysis

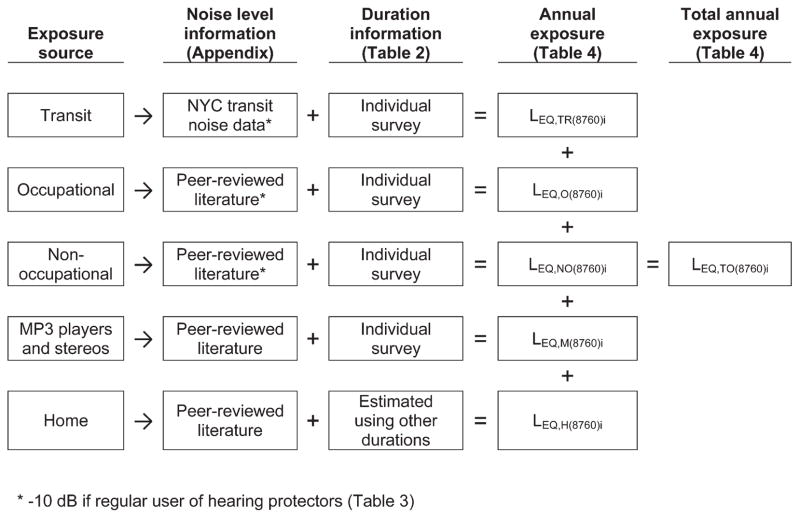

Data were entered using MS Access (Microsoft, Redmond, WA) and imported into Intercooled Stata 10.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) for analysis. We estimated exposures for each survey respondent using the following information (Figure 1): noise level for each source, annual duration for each source, annual exposure for each source, and, finally, total annual exposure across all sources.

Figure 1.

Overview of the study data.

Estimation of Annual Duration for Each Source

Each subjects’ reported frequency and duration of exposure for four noise sources (occupational, transit, nonoccupational, and MP3 player use) were multiplied together to estimate annual exposure durations for those sources. Annual time spent at home and doing other miscellaneous activities was estimated as 8760 h/year – occupational duration – nonoccupational duration – transit duration. The total time spent working, doing nonoccupational activities, and at home and doing other miscellaneous activities therefore equaled exactly 8760 h (one year) for each subject. Time spent using MP3 players was not constrained to 8760 h, since listening to music is not mutually exclusive with the other exposure sources.

Estimation of annual exposure for each source

We used eqs 1–3 to accomplish the first goal of our study, estimation of exposures associated with transit use, occupational and nonoccupational activities, MP3 player use, and time at home and doing other miscellaneous activities. In each equation, we normalized the exposure to 8760 h, which allowed for direct comparison of exposures that occurred over different durations. This normalization treats each source as if it were the only noise exposure that occurred during a one year interval. We used eq 1

| (1) |

to estimate annual transit noise exposures LEQ,TR(8760)i for each subject, where w is the annual wait time and r is the annual ride time for each of the j transit types and L is the transit-specific LEQ level (Supporting Information, Table S1). We subtracted 10 dBA from the relevant LEQ level for subjects who reported “always” or “regularly” using hearing protection while using transit. We assigned this 10 dBA value on the basis of extensive literature documenting the relatively low attenuation achieved by many users of hearing protection;22–24 however, it is important to note that some users may achieve essentially no attenuation from hearing protectors, while others may achieve upward of 30 dBA. No LEQ adjustments were made for subjects who used hearing protectors less than regularly.

We estimated annual nonoccupational exposures LEQ,NO(8760)i similarly, summing reported durations and levels for each of the j nonoccupational activities for each subject as in eq 1. We again accounted for hearing protector use during each nonoccupational activity by incorporating a 10 dBA attenuation value for regular users.

We estimated annual occupational (LEQ,O(8760)i) exposures for each subject using eq 2, where LO is the LEQ level for occupation j (Supporting Information, Table S1).

| (2) |

Hearing protector use was treated as above. The occupational LEQ for subjects reporting that their exposure was in the highest category of a three-point perceived noise exposure intensity scale was increased by 2 dBA, and those reporting the lowest category had their levels reduced by 2 dBA.25 The occupational LEQ for subjects reporting “quiet office work” was reduced to 70 dBA.

We estimated each subjects’ annual MP3 player (LEQM(8760)i) exposure using eq 3, where M indicates MP3 player.

| (3) |

Equation 3 was also used to compute home and other miscellaneous activity (LEQ,H(8760)i) exposures, substituting home H duration and level for M duration and level. Unlike the previous equations, our estimates for MP3 player use and home and other miscellaneous exposures assigned a single LEQ level to all individuals (Supporting Information, Table S1).

Total annual exposures (LEQ,TO(8760)i) were estimated by logarithmically averaging the hearing protector-corrected levels and durations from all five exposure sources. The fraction F of total annual exposure energy associated with each of the n sources for each individual i was then determined using the following equation:

| (4) |

The estimates resulting from eq 4 addressed the second goal of our study, which was to compare the relative contribution of the various sources of noise to total annual exposure.

Analysis of Exposure Estimates

To address our first goal, we computed descriptive statistics for estimated annual durations and exposures for each of the five noise sources and for total duration and exposure across all sources. We used Student’s t tests for comparison of ordinal variables between transit users and non-users and χ2 tests for categorical variables. To address our second goal, we computed the percentage of exposures exceeding the recommended exposure limit of 70 dBA for each of the five sources, as well as for total exposure. We also computed the percentage of subjects with primary exposure from each of the five sources and the fraction of duration and exposure associated with each of the sources.

RESULTS

Surveys

We collected a total of 5054 surveys from street fair attendees. Following removal of subjects who did not live or work in NYC (n = 230) and who possibly did not meet our inclusion criteria (n = 239), 4585 valid surveys were available for analysis.

Use of Mass Transit

Of the valid surveys, 4436 (97%) reported using any form of transit and 149 (3%) were nonusers (Table 1). A greater fraction of nontransit users were female compared to transit users. The age distributions also differed significantly, with nonusers having a larger fraction of individuals aged 51 or greater (P < 0.05). About 10% more transit users worked in NYC compared to nonusers, while 15% more transit users lived in NYC; both differences were significant (P < 0.05). Among transit users, 2509 (58%) reported using a combination of rail and buses, and 1468 (34%) used rail only (data not shown). A total of 234 participants (5%) used rail, ferries, and buses, and 125 (3%) used buses only. The distribution of occupations differed significantly between transit users and nonusers (P < 0.05), with the nontransit user group having a higher percentage of construction and retail workers and lower percentages of education/research and professional workers. The most common occupations in both groups were professional trades, construction and education/research.

Table 1.

Demographic Information for the Sample (n = 4585)

| variable/category | transit users

|

nontransit users

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | percentage | n | percentage | |

| total | 4436 | 100 | 149 | 100 |

| gendera | ||||

| male | 2394 | 54.0 | 62 | 41.6 |

| female | 2042 | 46.0 | 87 | 58.4 |

| agea | ||||

| 18–35 | 1587 | 35.8 | 33 | 22.1 |

| 36–50 | 1209 | 27.3 | 41 | 27.5 |

| 51–65 | 1213 | 27.3 | 57 | 38.3 |

| 66–80 | 390 | 8.8 | ||

| 81–97 | 37 | 0.8 | 18 | 12.1 |

| work in New Yorka | 2709 | 61.1 | 107 | 71.8 |

| live in New Yorka | 4229 | 95.3 | 118 | 79.2 |

| occupationa | 4436 | 100 | 149 | 100 |

| “noisy” occupations | 1033 | 23.2 | 50 | 33.6 |

| agriculture | 12 | 0.3 | ||

| construction | 396 | 8.9 | 24 | 16.1 |

| entertainment | 209 | 4.7 | 8 | 5.4 |

| food services | 161 | 3.6 | 8 | 5.4 |

| landscaping | 5 | 0.1 | ||

| maintenance | 93 | 2.1 | ||

| manufacturing | 55 | 1.2 | 1 | 0.7 |

| military | 22 | 0.5 | 4 | 2.7 |

| transportation | 58 | 1.3 | 5 | 3.4 |

| utility | 22 | 0.5 | ||

| “quiet” occupations | 3228 | 72.7 | 95 | 63.7 |

| education/research | 625 | 14.1 | 13 | 8.7 |

| healthcare | 353 | 8.0 | 9 | 6.0 |

| professional | 1623 | 36.6 | 43 | 28.9 |

| retail | 209 | 4.7 | 13 | 8.7 |

| homemaker | 115 | 2.6 | 3 | 2.0 |

| retired | 303 | 6.8 | 14 | 9.4 |

| unemployed | 175 | 3.9 | 4 | 2.7 |

χ2 test between transit users and nonusers, P < 0.05.

Annual Exposure Durations

Table 2 presents exposure durations for each of the five noise sources. Occupational durations are presented for jobs classified as “noisy” (LEQ levels over 80 dBA, Supporting Information, Table S1) and “quiet”. Nontransit users in noisy occupations reported significantly higher annual work hours than transit users (P < 0.01). Transit users spent an average of 381 h annually riding transit, with the majority of time spent on rail. Slightly less than half of the subjects in both groups reported participating in nonoccupational activities; nontransit users reported about 100 h more annually in these activities on average. The most common nonoccupational activities in both groups were attending concerts and sporting events. Over 70% of subjects in both groups reported MP3 player use, with transit users listening nearly 150 h more annually on average than non-transit users. Nontransit users spent about 262 h more annually at home and doing other miscellaneous activities than transit users.

Table 2.

Annual Exposure Durations (n = 4585)

| source | transit users

|

nontransit users

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | percentage | estimated duration (h)

|

n | percentage | estimated duration (h)

|

|||

| mean | SD | mean | SD | |||||

| total | 4436 | 100 | 8760 | 0 | 149 | 100 | 8760 | 0 |

| occupationala | 4436 | 100 | 1525 | 914 | 149 | 100 | 1610 | 968 |

| “noisy” occupations (agriculture, construction, entertainment, food services, landscaping, maintenance, manufacturing, military, transportation, utility)a | 1033 | 23.2 | 1671 | 698 | 50 | 33.6 | 1946 | 679 |

| “quiet” occupations (education/research, healthcare, professional, retail, homemaker, retired, unemployed) | 3403 | 76.7 | 1481 | 967 | 99 | 66.4 | 1440 | 1048 |

| transit | 4436 | 100 | 381 | 383 | ||||

| rail | 4305 | 97.0 | 293 | 314 | ||||

| platform | 72 | 100 | ||||||

| vehicle | 221 | 256 | ||||||

| bus | 2923 | 65.9 | 139 | 161 | ||||

| platform | 47 | 61 | ||||||

| vehicle | 91 | 122 | ||||||

| ferry | 284 | 6.4 | 75 | 141 | ||||

| platform | 30 | 67 | ||||||

| vehicle | 45 | 83 | ||||||

| nonoccupational | 2113 | 47.6 | 184 | 394 | 62 | 41.6 | 293 | 546 |

| play in band | 240 | 5.4 | 263 | 482 | 3 | 2.0 | 108 | 115 |

| concerts | 1246 | 28.1 | 53 | 86 | 30 | 20.1 | 46 | 44 |

| sporting eventsa | 1125 | 25.4 | 68 | 141 | 32 | 21.5 | 186 | 626 |

| power tools | 590 | 13.3 | 136 | 329 | 28 | 18.8 | 156 | 263 |

| motorcycle | 97 | 2.2 | 616 | 498 | 6 | 4.0 | 600 | 438 |

| MP3 players and stereosa | 3456 | 77.9 | 799 | 535 | 107 | 71.8 | 648 | 484 |

| home/other miscellaneous activitiesa | 4436 | 100.0 | 6766 | 1025 | 149 | 100.0 | 7028 | 1060 |

Student’s t test, transit users versus nonusers, P < 0.05.

Use of Hearing Protection

Reported use of hearing protection was low during most activities (Table 3). Occupational use is presented for noisy and quiet jobs as described above. Overall, regular hearing protection use during at least one activity was reported by 11% of transit users and 9% of nonusers. Roughly 4% of subjects in both groups regularly used hearing protectors at work. In both groups, a higher percentage of subjects in noisy occupations reported regular hearing protector use compared to those in quiet occupations. Between 4% and 6% of transit users wore hearing protectors regularly during transit use. Hearing protection was more common for nonoccupational activities, and use patterns were generally similar between the two groups.

Table 3.

Use of Hearing Protection (n = 4585)

| source | transit users

|

nontransit users

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | “regular” hearing protector user

|

N | “regular” hearing protector user

|

|||

| n | percentage | n | percentage | |||

| any | 4436 | 492 | 11.1 | 149 | 14 | 9.6 |

| occupational | 3829 | 143 | 3.7 | 128 | 6 | 4.7 |

| “noisy” occupations (agriculture, construction, entertainment, food services, landscaping, maintenance, manufacturing, military, transportation, utility) | 1033 | 95 | 9.2 | 50 | 4 | 8.0 |

| “quiet” occupations (education/research, healthcare, professional, retail, homemaker, retired, unemployed) | 3403 | 63 | 1.8 | 99 | 2 | 2.0 |

| transit | ||||||

| rail | 4305 | 177 | 4.1 | |||

| bus | 2923 | 152 | 5.2 | |||

| ferry | 284 | 17 | 6.0 | |||

| nonoccupational | ||||||

| play in banda | 240 | 67 | 27.9 | 3 | 0 | 0.0 |

| concerts | 1246 | 231 | 18.5 | 27 | 3 | 11.1 |

| sporting events | 1125 | 95 | 8.4 | 29 | 2 | 6.9 |

| power toolsa | 590 | 170 | 28.8 | 28 | 10 | 35.7 |

χ2 test, transit users versus nonusers, P < 0.05.

Commute Noise Exposure Validation

Research staff made a total of 45 simulated commutes, with an average duration of 34.5 ± 3.4 min (data not shown). On average, our predicted LEQ exposures for these simulated commutes were within 0.3 ± 3.1 dBA of the measured exposures. These results increase our confidence in the transit exposure estimates we present here.

Annual Noise Exposures

Annual source-specific and total LEQ(8760)i exposures are summarized by transit use in Table 4. Transit users had a total annual exposure that was on average almost 1 dBA higher than that of nontransit users (P < 0.05), while home and other miscellaneous activity exposures were essentially the same (about 63 dBA). Annual average occupational and nonoccupational exposures were 2–3 dBA higher among nontransit users, while annual average MP3 player exposures were about 1 dBA higher among transit users; all of these differences were statistically significant (P < 0.05). Variability in annual exposures was greater among nontransit users for most sources of exposure.

Table 4.

Estimated Annual Hearing Protector-Adjusted Noise Exposures (n = 4585)

| source | transit users

|

nontransit users

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n |

LEQ(8760)i

|

n |

LEQ(8760)i

|

|||

| mean | SD | mean | SD | |||

| totala | 4436 | 76.8 | 5.0 | 149 | 76.0 | 6.8 |

| occupationala | 3829 | 66.7 | 7.2 | 128 | 69.2 | 8.4 |

| transit | 4436 | 65.0 | 4.4 | |||

| MP3 players and stereosa | 3456 | 74.9 | 2.7 | 107 | 74.0 | 2.5 |

| nonoccupationala | 2113 | 72.6 | 6.9 | 62 | 75.5 | 7.6 |

| home/other miscellaneous activities | 4436 | 63.3 | 0.7 | 149 | 63.2 | 0.7 |

Student’s t test, transit users versus nonusers, P < 0.05.

Over nine in ten transit users and nearly nine in ten nonusers had annual total exposures that exceeded the EPA-recommended limit (Table 5). The source with the highest percentage of annual exposures over 70 dBA was MP3 players for both users (78%) and nonusers (72%). About one-third of nontransit users had annual exposures over 70 dBA from occupational noise and another one-third from nonoccupational activities. Transit users had a larger fraction of annual exposures over 70 dBA from nonoccupational activities (31%) than occupational activities (23%). Ten percent of transit users had annual transit exposures over 70 dBA. Neither group had any estimated exposures over 70 dBA from time at home and other miscellaneous activities. For 59% of transit users and 44% of nonusers, MP3 player use was the primary exposure source. Occupational exposure was the next most important source for both groups, followed by nonoccupational exposure. Transit was the primary exposure for one in ten transit users. The 440 individuals for whom transit represented the primary exposure source spent significantly more time riding transit than users with other primary sources (564 vs 349 annual hours, respectively, P < 0.001, data not shown). Home and other miscellaneous activities were the primary source of exposure for 3% of nonusers and <1% of transit users.

Table 5.

Comparison of Annual Hearing Protector-Adjusted Noise Exposures (n = 4585)

| source | percentage of subjects

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| transit users (n = 4436)

|

nontransit users (n = 149)

|

|||

| LEQ(8760)i > 70 dBA | primary source | LEQ(8760)i > 70 dBA | primary source | |

| total | 90.6 | 87.3 | ||

| occupational | 23.2 | 16.1 | 32.9 | 31.5 |

| transit | 10.0 | 10.4 | ||

| MP3 players and stereos | 77.9 | 59.1 | 71.8 | 44.3 |

| nonoccupational | 31.1 | 15.1 | 31.5 | 21.4 |

| home/other miscellaneous activities | 0.0 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 3.1 |

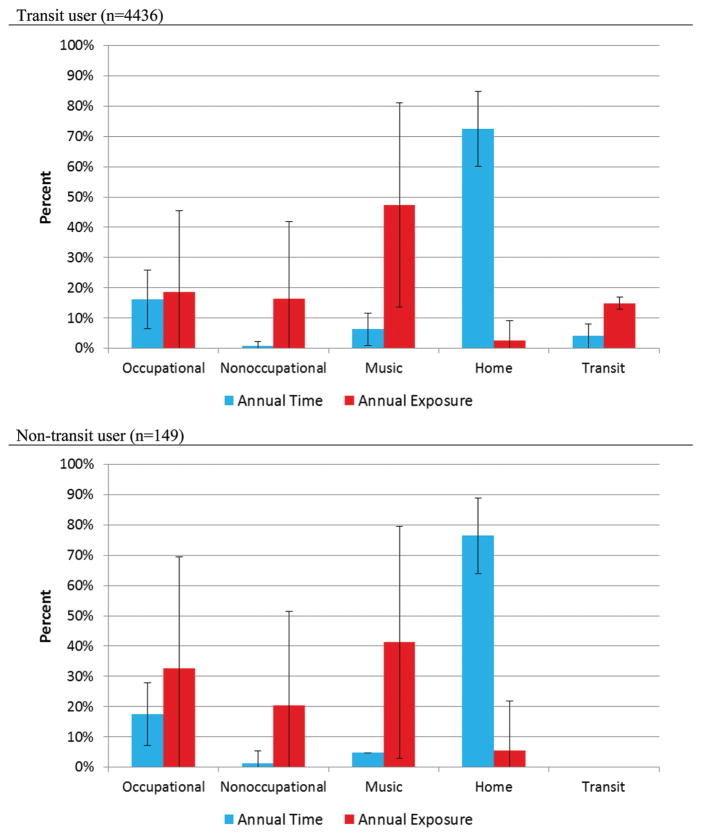

Of the five sources, transit showed the smallest variability in duration and exposure; variability in both factors was generally large for the other sources (Figure 2). Among transit users, home and other miscellaneous activities represented nearly 75% of annual time on average, but contributed less than 3% of total exposure. Conversely, listening to music accounted for 6% of annual time, but contributed almost 50% of total annual exposure on average, and nonoccupational activities contributed <1% of annual time, but contributed almost 20% of annual exposure. Occupational activities contributed somewhat less than 20% of annual time and annual exposure, and transit use contributed 4% of annual time and 15% of annual exposure. Compared to transit users, occupational exposures among non-users contributed a much larger percentage of total annual exposure (nearly double) than transit users, and MP3 player use contributed about 6% less.

Figure 2.

Mean fraction of annual duration and noise exposure (adjusted for hearing protector use) by source.

DISCUSSION

Our results indicate that a substantial fraction of individuals who work or reside in NYC may be at risk of NIHL. The first goal of our study was to estimate and compare annual noise exposures associated with five sources of exposure: use of mass transit, occupational and nonoccupational activities, listening to music, and time spent at home and doing other miscellaneous activities. Transit users had significantly higher total annual exposures than nonusers on average, although the absolute difference was only 1 dBA. Among transit users, mean annual exposures associated with transit exceeded those associated with time spent at home and doing other miscellaneous activities, but were substantially lower than exposures associated with nonoccupational activities and MP3 player use. Mean occupational and nonoccupational exposures among nontransit users were higher than among transit users, while MP3 player exposures were lower. Use of hearing protectors was uncommon among both transit users and non-users and had little impact on our exposure estimates, resulting in an insignificant <0.01 dBA reduction in estimated exposures across all subjects. The second goal of our study was to compare the relative contribution of the five sources of exposure to total exposure and to compare these exposures to the recommended exposure limit of 70 dBA. Listening to MP3 players was by far the most important exposure in our study and was the primary source of exposure for well over half of transit users and nearly half of nonusers. Time spent at home contributed the vast majority of annual hours for most subjects, but contributed a very small fraction of exposure, while time spent listening to MP3 players contributed only a small fraction of time, but the majority of exposure. When we compared our source-specific and total annual exposure estimates to the 70 dBA recommended limit, the percentage of subjects with overexposures was quite high. About 91% of transit users and 87% of nonusers were estimated to exceed this level annually. The mean total annual exposures for transit users and nonusers were about 77 and 76 dBA, respectively, and were substantially greater than the 70 dBA annual exposure limit; a 3 dBA increase in exposure represents a doubling of sound energy. One in ten transit users exceeded the recommended limit from their transit use alone.

No previous studies appear to have estimated annual noise exposures for a large sample of individuals who reside or work in a highly urbanized environment. However, several studies have conducted noise dosimetry measurements on small groups of subjects for periods of days to one week. Measured transit exposures have ranged from 71 to 79 dBA26–28 and agree quite well with our mean estimated annual transit exposure (76.9 ± 4.8 dBA) when it is not normalized to 8760 h (data not shown). Several of these studies found that urban transit users received 3–13% of their total measured exposure from transit use,27,28 results that are again consistent with our estimated contribution of 10%. The strong agreement between these different estimates of transit-related noise exposure suggests that our results may be generalizable to individuals living in other urban areas.

Our estimated total annual exposures (about 77 dBA for transit users and 76 dBA for nonusers) generally agree with noise exposures measured via dosimetry over periods of days to one week. In fact, the literature describing short-term measurements is remarkably consistent across both time and location. Week-long measurements on suburban U.S. individuals29 showed mean exposures between 74.5 and 76 dBA. Studies on urban dwellers, including one day measurements in Italy26 and China,27 two to four day measurements in the United States,30 and one week measurements in Spain,28 have shown mean exposures between 74.5 and 75.6 dBA. In all of these studies, the percentage of measured exposures above 70 dBA was roughly 80%—quite high, but nevertheless about 10% below our estimate for NYC transit users.

The occupational usage rate of hearing protectors was quite low among our subjects (about 4% for transit users and non-users), which is partially due to the fact that the majority of subjects (3502, or 77%) worked in quiet occupations where no noise exposure was expected or were homemakers or retirees or were unemployed. Among those who reported a noisy occupation, hearing protector usage rates were somewhat higher, ranging from 11% of individuals in construction to 16% in transit and manufacturing. These rates are lower than among manufacturing workers,31 but are consistent with industries such as construction32 and agriculture.33 The low rates of hearing protector use during nonoccupational activities are consistent with the results of other U.S. studies.34

The sample of survey respondents analyzed here represented a wide range of ages, occupations, and reported nonoccupational activities. The age and gender distribution of our sample was similar to the latest census data for NYC35 after consideration of the fact that our sample omitted individuals under 18 years of age, while the census covered all ages. As we did not collect race/ethnicity information, we cannot compare our sample to the NYC census. However, the results of our earlier pilot survey of transit users suggested that our sampling approach produced a sample that was roughly representative of the ethnic breakdown from the NYC census.35 The percentage of transit users in this study—97% of our sample—was much greater than the 55% of NYC residents identified as transit users by a 2004 community survey.36

As with any modeling study, our study had a number of limitations. First, given that all of our survey respondents were in NYC, our results may not be generalizable across the entire U.S. transit ridership. We believe our results are likely generalizable to other urban U.S. settings with aging infrastructure, however, and given the sizable population and high fraction of transit users in NYC, our results are meaningful even without generalizability.

Second, our estimates of occupational, nonoccupational, home and other miscellaneous activities, and MP3 player exposures relied on noise levels drawn from the peer-reviewed literature. The absence of validated exposure matrices for different occupations, and for different nonoccupational activities, is a notable weakness in the scientific literature given the ubiquity of noise exposure. The generic nature of the estimates used here undoubtedly introduced error into our exposure estimates. We partially addressed individual variability in occupational noise levels through modification of assigned levels based on survey responses concerning subjects’ perceived noise exposure intensity, work in a quiet environment, and use of hearing protectors. We were not able to address individual variability in nonoccupational, home, or other miscellaneous activities beyond consideration of hearing protectors, or at all for MP3 player noise levels. In particular, the single music and home noise levels used in this study undoubtedly introduced error into our exposure estimates. While our estimates incorporated individual variation in MP3 player listening duration and time spent at home and doing other miscellaneous activities, we could not account for the fact that listening levels vary widely across individuals37,38 and environments.39 Preferred MP3 player listening levels, in particular, vary widely, with measured LEQ listening levels ranging from around 80 dBA40,41 to 90 dBA or more.42,43 The assigned level of about 86 dBA used here represents a reasonable midpoint in the range of values, but undoubtedly resulted in overestimated annual MP3 player exposures for individuals who prefer very quiet listening levels and in underestimated annual MP3 player exposures for individuals who prefer very loud listening levels. There are likely also large geospatial gradients in home and other activity noise levels.

Third, we relied heavily on self-reported information from survey respondents. Given our brief contact with subjects, validation of self-reported activity types and durations or use of hearing protectors was infeasible. We attempted to minimize potential response biases by focusing only on recent exposures (e.g., within the past seven days) where possible and requiring recall of no more than the previous year for infrequent events (e.g., attending baseball games or concerts). The possibility of social desirability bias was low, given the fact that none of the survey items addressed sensitive issues. Research staff stressed the confidential and anonymous nature of the data collected to further minimize this potential bias.

Finally, we developed individual-level exposure estimates for the five sources of noise that we believe likely represent the majority of potential noise exposure for urban workers and residents. However, there are possible sources that were excluded from our study, most notably use of firearms, which has been suggested as being a more important risk factor for NIHL than occupational noise.44 This exposure is potentially quite important, but no validated models exist with which to integrate impulsive exposures into an annual average exposure.45 Quantitative integration of firearms exposure into our estimates would undoubtedly increase our estimated exposures substantially for some individuals, and the addition of other excluded noise sources would only serve to increase estimated total exposures for our sample.

Our results suggest that the risk for NIHL—and for other non-auditory effects of noise, including stress, cardiovascular disease, and hypertension—is high among residents of NYC and perhaps among residents of other densely populated U.S. areas and that further research on urban noise exposures is warranted. Our results further suggest that the traditional approach to noise exposure assessment —e.g., in a source-by-source fashion and with an emphasis on occupational noise—may result in substantial underestimates of the risk of hearing loss and other health effects and that more holistic approaches such as the one described here are warranted.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (Grant RES 015347A). We are indebted to the participating subjects and gratefully acknowledge the efforts of John McGovern and Ivette Sanchez for assistance with data collection.

NOMENCLATURE

- LEQ

equivalent continuous average noise exposure

- dBA

A-weighted decibels

- NYC

New York City

- NIHL

noise-induced hearing loss

- EPA

Environmental Protection Agency

- WHO

World Health Organization

Footnotes

Supporting Information. Noise levels used to estimate annual noise exposures associated with transit use, occupational and nonoccupational activities, MP3 player and stereo use, and home and other miscellaneous activities. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.United Nations. State of the World Population 2007: Unleashing the Potential of Urban Growth. United Nations Population Fund; New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Serradell J. [accessed April 20, 2011];World Metro Database. http://micro.com/metro/table.html.

- 3.Dennekamp M, Carey M. Air quality and chronic disease: Why action on climate change is also good for health. N S W Public Health Bull. 2011;21(5–6):115–21. doi: 10.1071/NB10026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zimmerman R. Mass transit infrastructure and urban health. J Urban Health. 2005;82(1):21–32. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lindblom M. Seattle Times. Sep 25, 2009. Sound transit calls light-rail noise a public-health problem. [Google Scholar]

- 6.EPA. EPA Report 550/9-74-004. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency; Washington, DC: 1974. Information on Levels of Environmental Noise Requisite To Protect Public Health and Welfare with an Adequate Margin of Safety. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berglund B, Lindvall T, Schwela D, editors. WHO. Guidelines for Community Noise. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gan WQ, Davies HW, Demers PA. Exposure to occupational noise and cardiovascular disease in the United States: The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2004. Occup Environ Med. 2011;68(3):183–90. doi: 10.1136/oem.2010.055269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tomei G, Fioravanti M, Cerratti D, Sancini A, Tomao E, Rosati MV, Vacca D, Palitti T, Di Famiani M, Giubilati R, De Sio S, Tomei F. Occupational exposure to noise and the cardiovascular system: a meta-analysis. Sci Total Environ. 2011;408(4):681–9. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2009.10.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Passchier-Vermeer W, Passchier WF. Noise exposure and public health. Environ Health Perspect. 2000;108(Suppl 1):123–31. doi: 10.1289/ehp.00108s1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seidman MD, Standring RT. Noise and quality of life. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2011;7(10):3730–8. doi: 10.3390/ijerph7103730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.EPA. Protective Noise Levels: Condensed Version of EPA Levels Document. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Noise Abatement & Control; Springfield, VA: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Kluizenaar Y, Gansevoort RT, Miedema HM, de Jong PE. Hypertension and road traffic noise exposure. J Occup Environ Med. 2007;49(5):484–92. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e318058a9ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Willich SN, Wegscheider K, Stallmann M, Keil T. Noise burden and the risk of myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2006;27(3):276–82. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neitzel R, Gershon RR, Zeltser M, Canton A, Akram M. Noise levels associated with New York City’s mass transit systems. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(8):1393–9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.138297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gershon RR, Neitzel R, Barrera MA, Akram M. Pilot survey of subway and bus stop noise levels. J Urban Health. 2006;83(5):802–12. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9080-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dinno A, Powell C, King MM. A study of riders’ noise exposure on Bay Area Rapid Transit trains. J Urban Health. 2011;88(1):1–13. doi: 10.1007/s11524-010-9501-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taplin M. [accessed April 22, 2011];A world of trams and urban transit. http://www.lrta.org/world/worlduz.html#US.

- 19.Bureau, U. C. [accessed April 22, 2011];American Community Survey 2006, Table S0802, Means of Transportation to Work by Selected Characteristics. http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/STTable?_bm=y&-state=st&-context=st&-qr_name=ACS_2006_EST_G00_S0802&-ds_name=ACS_2006_EST_G00_&-tree_id=306&-redoLog=true&-_caller=geoselect&-geo_id=16000US3651000&-format=&-_lang=en.

- 20.American Public Transportation Association (APTA) [accessed April 22, 2011];Public Transportation Ridership Report, Fourth Quarter. 2010 http://www.apta.com/resources/statistics/Documents/Ridership/2010_q4_ridership_APTA.pdf.

- 21.Kincaid J, Fishburne R, Rogers R, Chissom B. Research Branch Report 8-75. U.S. Navy, Naval Technical Training; Memphis, TN: 1975. Derivation of New Readability Formulas (Automated Readability Index, Fog Count and Flesch Reading Ease Formula) for Navy Enlisted Personnel. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berger EH, Franks JR, Lindgren F. International review of field studies of hearing protector attenuation. In: Axlesson A, Borchgrevink H, Hamernik RP, Hellstrom P, Henderson D, Salvi RJ, editors. Scientific Basis of Noise-Induced Hearing Loss. Thieme Medical Publishers, Inc; New York: 1996. pp. 361–377. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Williams W. Instruction and the improvement of hearing protector performance. Noise Health. 2004;7(25):41–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lempert BL, Edwards RG. Field investigations of noise reduction afforded by insert-type hearing protectors. Am Ind Hyg Assoc J. 1983;44(12):894–902. doi: 10.1080/15298668391405913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neitzel R, Daniell W, Sheppard L, Davies H, Seixas N. Evaluation and comparison of three exposure assessment techniques. J Occup Environ Hyg. 2011;8(5):310–323. doi: 10.1080/15459624.2011.568832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Orlando P, Perdelli F, Cristina ML, Piromalli W. Environmental and personal monitoring of exposure to urban noise and community response. Eur J Epidemiol. 1994;10(5):549–54. doi: 10.1007/BF01719571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zheng D, Cai X, Song H, Chen T. Study on personal noise exposure in China. Appl Acoust. 1996;48(1):59–70. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Diaz C, Pedrero A. Sound exposure during daily activities. Appl Acoust. 2006;67:271–283. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schori T, McGatha E. A real-world assessment of noise exposure. Sound Vib. 1978:24–30. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Neitzel R, Seixas N, Olson J, Daniell W, Goldman B. Nonoccupational noise: Exposures associated with routine activities. J Acoust Soc Am. 2004;115(1):237–45. doi: 10.1121/1.1615569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tak S, Davis RR, Calvert GM. Exposure to hazardous workplace noise and use of hearing protection devices among US workers—NHANES, 1999–2004. Am J Ind Med. 2009;52(5):358–71. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Suter AH. Construction noise: Exposure, effects, and the potential for remediation; a review and analysis. Am Ind Hyg Assoc J. 2002;63(6):768–89. doi: 10.1080/15428110208984768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carpenter WS, Lee BC, Gunderson PD, Stueland DT. Assessment of personal protective equipment use among midwestern farmers. Am J Ind Med. 2002;42(3):236–47. doi: 10.1002/ajim.10103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Widen SE, Holmes AE, Johnson T, Bohlin M, Erlandsson SI. Hearing, use of hearing protection, and attitudes towards noise among young American adults. Int J Audiol. 2009;48(8):537–45. doi: 10.1080/14992020902894541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.U.S. Census Bureau. 2005–2009 American Community Survey: New York City. New York: Feb 17, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 36.U.S. Census Bureau. Table B08406. Sex of Workers by Means of Transportation for Workplace Geography—Universe: Workers 16 Years and Over. [accessed April 21, 2011];2004 American Community Survey. http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/DTGeoSearchByListServlet?ds_name=ACS_2004_EST_G00_&_lang=en&_ts=170243153266.

- 37.Levey S, Levey T, Fligor BJ. Noise exposure estimates of urban MP3 player users. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2011 Feb;54(1):263–77. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2010/09-0283). (Epub: Aug. 5, 2010) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Williams W. Noise exposure levels from personal stereo use. Int J Audiol. 2005;44(4):231–6. doi: 10.1080/14992020500057673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hodgetts W, Szarko R, Rieger J. What is the influence of background noise and exercise on the listening levels of iPod users? Int J Audiol. 2009;48(12):825–32. doi: 10.3109/14992020903082104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Williams W. Trends in listening to personal stereos. Int J Audiol. 2009;48(11):784–8. doi: 10.3109/14992020903037769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kumar A, Mathew K, Alexander SA, Kiran C. Output sound pressure levels of personal music systems and their effect on hearing. Noise Health. 2009;11(44):132–40. doi: 10.4103/1463-1741.53357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Levey S, Levey T, Fligor BJ. Noise exposure estimates of urban MP3 player users. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2011;54(1):263–77. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2010/09-0283). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Torre P., III Young adults’ use and output level settings of personal music systems. Ear Hear. 2008;29(5):791–9. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e31817e7409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kryter KD. Effects of nosocusis, and industrial and gun noise on hearing of U.S. adults. J Acoust Soc Am. 1991;90(6):3196–201. doi: 10.1121/1.401428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Neitzel R, Seixas N, Goldman B, Daniell W. Contributions of non-occupational activities to total noise exposure of construction workers. Ann Occup Hyg. 2004;48(5):463–473. doi: 10.1093/annhyg/meh041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.