Abstract

Background

Infant HIV-1 infection is associated with impaired neurologic and motor development. Antiretroviral therapy (ART) has the potential to improve developmental outcomes but the relative contributions of pre-ART disease status, growth, treatment regimen, and ART response during infancy are unknown.

Methods

Kenyan ART-naive infants <5 months old initiated ART and had monthly assessment of age of full neck control, unsupported walking, and monosyllabic speech during 24 months of follow-up. Pre- and post-ART correlates of age at milestone attainment were evaluated using t-tests or multivariate linear regression.

Results

Among 99 infants, pre-ART correlates of later milestone attainment included: underweight and stunted (neck control, walking and speech, all P-values <0.05), missed prevention of mother-to-child transmission (P=0.04) (neck control), previous hospitalization, WHO Stage III/IV, low CD4 count, and wasting (speech and walking, all P-values <0.05), and low maternal CD4 (speech, P=0.04). Infants initiated ART at a median of 14 days following enrollment. Infants receiving nevirapine- vs lopinavir/ritonavir-based ART attained later speech (18.1 vs. 15.5 months, P=0.003). Adjusting for pre-ART level, lower 6-month gain in CD4% was associated with later walking (0.18 months earlier per unit increase in CD4%; P=0.004) and speech (0.12 months earlier per unit increase in CD4%; P=0.05), and lower 6-month gains in weight-for-age (P=0.009), height-for-age (P=0.03), and weight-for-height (P=0.02) were associated with later walking.

Conclusion

In HIV-infected infants, compromised pre-ART immune and growth status, poor post-ART immune and growth responses, and use of nevirapine- vs. lopinavir/ritonavir-based ART were each associated with later milestone attainment. The long-term consequences of these delays are unknown.

Keywords: Sub-Saharan Africa, infant, antiretroviral therapy, HIV-1, neurocognitive, neurodevelopment

INTRODUCTION

Access to early infant HIV-1 diagnosis and treatment in sub-Saharan Africa may dramatically improve infant survival.1 As these infants mature, it will be increasingly important to optimize pediatric HIV care for neurodevelopmental outcomes.

Perinatal HIV can cause a spectrum of neurological and developmental disorders with varying severity, timing and presentation,2,3 and including failed or delayed attainment of age-appropriate milestones.4–7 Mechanisms involve an inflammatory state in the brain, mediated by HIV-infected microglial cells and activated macrophages. Neuronal injury occurs via pro-inflammatory, pro-apoptotic or other neurotoxic molecules.3,8 Local virus replication or ongoing infiltration of HIV into the central nervous system (CNS) may also play a role.3,8 In small pediatric studies, cofactors for HIV encephalopathy include higher HIV levels in cerebral spinal fluid and in plasma, immunosuppression and microcephaly.3,9,10 Similarly, an AIDS diagnosis,6,7 higher plasma HIV levels,11 stunting and microcephaly,11 and earlier timing of HIV acquisition12,13 are associated with motor and cognitive delays in infants. In birth cohorts with no or limited access to combination antiretroviral therapy (ART), rates of motor and cognitive delays, were 30–36% and 26–36% by 24 months, respectively.4,5,14 A subset of untreated HIV-infected children may survive to age two4,5 or adolescence with no apparent developmental deficit.15,16

Following the advent of combination ART in developed settings, the incidence of progressive HIV encephalopathy in children declined.17,18 By contrast, the estimated prevalence of learning disabilities, below normal cognitive scores, or language impairment was high (25%–42%) in cohorts with combination ART,14,19–21 although many of these children were born prior to combination ART.

Thus, the extent to which combination ART, if provided during infancy, can preserve or salvage subtle developmental deficits is unknown. In small cohorts, improved language22 and cognitive scores,23 reversal of neurologic abnormalities,24 and reduced brain atrophy23 were observed following ART or change in regimen. In 91 US/ Puerto Rican infants, cognitive and motor scores improved modestly with protease-inhibitor based regimens.25 In the South African Children with HIV Early Antireroviral Therapy (CHER) study, asymptomatic infants diagnosed at <3 months of age and randomized to early ART had higher cognitive and motor test scores at age 11 months than infants with deferred ART,26 and early-treated infants had similar scores versus HIV-uninfected infants. Whether these encouraging results can be realized in a broader African context is unknown.

Within the framework of early HIV testing and immediate ART in infants,27 pediatric HIV programs may be able to implement regimens that optimize neurodevelopmental outcomes. In this study, we examined modifiable cofactors, including pre-ART disease severity, and growth status, type of regimen, and response to treatment, of later milestone attainment in HIV-infected infants diagnosed by 5 months of age, but who often had severe immune compromise prior to ART.

METHODS

Study Population

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the University of Washington and the University of Nairobi / Kenyatta National Hospital Institutional Review Boards. HIV-infected infants were enrolled into a randomized clinical trial (Optimizing Pediatric HIV-1 Therapy 03 [OPH03])28 involving a 2-year pre-randomization phase during which all infants initiated ART at enrollment (NCT00428116). HIV-positive infants were identified from 2007–2009 during routine HIV screening at Nairobi City Council Maternal Child Health clinics and hospital wards. Key enrollment eligibility criteria were HIV DNA detection with confirmation, age <5 months, and no prior ART, except for prevention of mother to child transmission (PMTCT).

A physical examination was administered to all infants at enrollment (pre-ART) and blood specimens were collected. Caregivers provided demographics and a blood specimen for CD4 testing. ART was initiated approximately 2 weeks after enrollment. First line ART was two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (typically zidovudine and lamivudine) and either nevirapine, or lopinavir/ritonavir for infants with exposure to nevirapine during PMTCT. Before or at enrollment, 99% of infants received trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (cotrimoxazole) prophylaxis in accordance with WHO recommendations.

At enrollment and monthly visits, attainment of milestones was assessed, with continued evaluation through the entire 2-year pre-randomization phase of the study. Milestones assessed included “full neck control” (neck control), “walking unsupported” (walking) and “able to say monosyllables” (speech). Age at attainment of each milestone was estimated by subtracting the infants’ date of birth from the date of the study visit at which the milestone was first observed or reported. For infants with neck control at enrollment, age at enrollment was a proxy for age at neck control. Milestones had been adapted from the Denver Developmental Screening Test.29 Neck control was defined as: infant could support his or her own head. Walking was defined as: child could take a few steps without needing support. Speech was determined by asking the caregiver whether the infant had started talking, and clinicians evaluated whether the infant was able to say one-syllable sounds or words. Clinicians did not record whether the infant had begun to use words in a specific context.

Milestones were assessed by one of four medical officers who consulted regularly with an on-site pediatrician (AL). Clinicians obtained parental report regarding milestones and attempted to directly observe milestones at all visits; however, whether determination of milestone status was through direct observation vs. parental report was not recorded.

Laboratory Testing

Confirmatory HIV DNA filter paper tests were performed as described.30 Enrollment and 6-monthly CD4 counts and percentages were obtained using flow cytometry. Plasma was separated from whole blood using density gradient centrifugation and cryopreserved at −70° C. Plasma specimens were shipped to Seattle, WA in liquid nitrogen and plasma HIV RNA levels at enrollment, one-month and 3-monthly post-ART were determined using the Gen-Probe HIV Viral Load Assay (San Diego, CA).31

Statistical Analysis

Z-scores for weight-for-age (WAZ), height-for-age (HAZ), weight-for-height (WHZ), and head circumference (HCZ) were calculated using WHO child growth standards.32 Underweight (WAZ), stunting (HAZ), wasting (WHZ), and microcephaly (HCZ) were defined as a z-score <−2. Kaplan-Meier survival analyses including all 99 infants were used to calculate median age of milestone achievement with censoring at loss to follow-up, withdrawal, or death. Median ages obtained using time-to-event data were similar to median ages obtained using continuous data for age at each milestone, which did not include censored infants. Comparisons between enrollment characteristics for infants included and excluded in analyses of attainment of neck control were performed using Wilcoxon rank sum tests for continuous variables and chi-square tests or fisher’s exact tests for dichotomous variables, as appropriate. Pre-ART and post-ART correlates of age at milestone attainment were examined using linear regression for continuous variables and t-tests for categorical variables; however, only data for t-tests are presented. Pre-ART vs. 6-month post-ART levels for CD4% and count, plasma HIV RNA levels, and growth parameters were compared using paired Wilcoxon sign-rank tests. Multivariate linear regression was used to examine the relation between 6-month change in post-ART immune, viral, and growth parameters and age at milestone achievement. These models were each adjusted for the corresponding pre-ART level alone. To explore interaction between the pre-ART WAZ, HAZ, and WHZ level and the 6-month change magnitude for each, adjusted models including interaction terms (computed by multiplying the pre-ART WAZ, HAZ, and WHZ level by the corresponding 6-month change level) were examined. To assess potential confounding between regimen type and sociodemographics and disease severity, comparisons between infants initiated on lopinavir/ritonavir- vs. nevirapine-based ART were performed using Wilcoxon rank sum tests for continuous variables and chi-square tests for dichotomous variables, and were limited to infants with data for speech (N=53). Multivariate linear regression analyses were used to examine the relation between ART regimen and age at speech, adjusted for potential confounders including age at ART, pre- and post-6-month ART plasma virus level (included as a continuous variable or as a dichotomous variable with either 1000 copies/ml or 400 copies/ml as a cut-off), prior hospitalization, WHO Stage, pre-ART WAZ, maternal CD4 count, and breastfeeding. Analyses were performed using Stata SE version 11.0 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA).

RESULTS

Cohort Characteristics

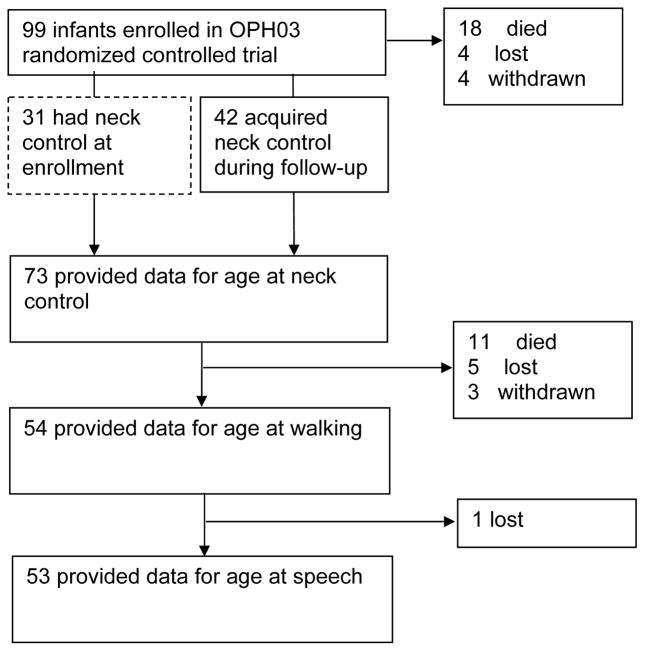

Ninety-nine HIV-infected infants aged 1.1–4.9 months were enrolled. Ages at neck control, walking and speech were available for 73, 54 and 53 infants, respectively (Fig. 1). Eighteen infants died, 4 were lost-to-follow-up (LTFU), and 4 withdrew prior to neck control. Eleven infants died, 5 were LTFU, and 3 withdrew prior to walking or speech. One infant was LTFU after walking but before speech. At the end of the 2-year pre-randomization phase, the median infant age was 28.0 months.

FIGURE 1.

Flow-diagram of infants included in analysis. 73, 54, and 53 infants had available data for neck control, walking, and speech, respectively and were included in analyses of correlates of age at milestone attainment.

Among the 73 infants who provided data for neck control, the median age at enrollment was 3.7 months (interquartile range [IQR], 3.0, 4.0) (Table 1). Slightly over half (57.4%) had received PMTCT. Most infants (87.2%) had breastfed and 79.0% were breastfeeding at enrollment. Infant caregivers were a median of 26 years (IQR, 22, 30) old and had a median of 9 years (IQR, 8, 11) of education. Almost all infants (97.3%) were cared for by their biological mother. Mothers had a median CD4 count of 370 cells/mm3 (IQR, 245, 480).

TABLE 1.

Pre-ART characteristics of HIV-infected infants*

| N | Median (IQR) or N (%) | |

|---|---|---|

|

Infant characteristics

| ||

| Age at enrollment (months) | 73 | 3.7 (3.0, 4.0)† |

| Male | 73 | 35 (48.0) |

| Birth weight (kg) | 68 | 3.1 (2.7, 3.4) |

| Received PMTCT | 68 | 39 (57.4) |

| Ever breastfed | 64 | 56 (87.2) |

| Currently breastfeeding | 62 | 49 (79.0) |

| Infant clinical, immunologic, virologic, and growth status | ||

| Ever hospitalized | 73 | 38 (52.1)† |

| WHO stage III/IV | 71 | 29 (40.9)† |

| Plasma HIV RNA (log10 copies/mm3) | 65 | 6.5 (6.0, 7.0)† |

| CD4% | 73 | 18 (14, 24) |

| CD4 count (cells/mm3) | 73 | 1,311 (794, 1,818) |

| WAZ | 73 | −2.0 (−3.4, −0.9)† |

| HAZ | 73 | −1.9 (−3.0, −0.8)† |

| WHZ | 73 | −0.6 (−1.6, 0.7) |

| HCZ | 73 | −0.5 (−1.4, 0.5)† |

| Primary caregiver characteristics | ||

| Biological mother | 73 | 71 (97.3) |

| Age (years) | 72 | 26 (22, 30) |

| Married | 73 | 57 (78.1) |

| Education (years) | 66 | 9 (8, 11) |

| Maternal CD4 count (cells/mm3) | 70 | 370 (245, 480) |

Includes infants surviving, or remaining enrolled in the study long enough to define attainment of neck control.

There were significant differences between the infants included in the analysis and those excluded (N=26) with respect to infant age (median, 3.4 months ; P=0.04), history of hospitalization (80.8%; P=0.01), WHO stage III/IV (72.0%; P=007), plasma HIV RNA level (median 6.9 log10 copies/mm3; P=0.05), WAZ (median, −3.6; P=0.0008), WHZ (median, −2.3; P=0.002), and HCZ z-score (median, −1.2; P=0.007). Infant feeding was not compared due to a low proportion of available observations.

ART, antiretroviral therapy; IQR, Interquartile range; PMTCT, prevention of mother-to-child transmission; WAZ, weight-for-age z-score; HAZ, height-for-age z-score; WHZ, weight-for-height z-score; HCZ, head circumference-for-age z-score.

At enrollment, infants were severely immunosuppressed: the median CD4% was 18% (IQR 14%, 24%) and plasma HIV RNA level was 6.5 log10 copies/mm3 (IQR 6.0, 7.0) (Table 1). Half of infants were underweight (49.3%), or stunted (46.6%), 19% were wasted (WHZ <−2), and 12.3% of infants were microcephalic (HCZ <−2). The subset of infants with attrition prior to neck control were generally more ill, with more frequent WHO stage III/IV diagnosis, and with lower growth z-scores (Table 1).

Pre-ART Correlates of Age at Milestone Attainment

Thirty-one infants had established neck control at enrollment and 42 additional infants attained neck control during follow-up (Fig. 1). Using Kaplan-Meier survival analyses to allow censoring, the median age of neck control achievement was 4.3 months (IQR, 3.6, 5.1). Among 73 infants with data for age at neck control, lack of receipt of PMTCT (P=0.04), WAZ <−2 (P=0.008) and HAZ <−2 (P=0.02) prior to ART were significantly associated with later age of neck control (Table 2). However, in analyses restricted to the 42 infants attaining neck control during follow-up, these associations were no longer apparent.

TABLE 2.

Pre-ART correlates of age at milestone achievement

| Correlate * | N | Mean (SD) age neck control achieved | P-value | N | Mean (SD) age walking achieved | P-value | N | Mean (SD) age speech achieved | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Received PMTCT | 39 | 4.1 (1.0) | 0.04 | 28 | 16.0 (2.7) | 0.1 | 28 | 16.7 (2.8) | 0.3 |

| No PMTCT | 29 | 4.7 (1.3) | 22 | 17.6 (4.0) | 21 | 17.6 (3.5) | |||

| Currently breastfeeding | 49 | 4.5 (1.2) | 0.3 | 40 | 16.3 (3.3) | 0.5 | 39 | 16.5 (2.4) | 0.2 |

| Not breastfeeding | 13 | 4.1 (0.9) | 11 | 17.1 (3.0) | 11 | 17.7 (3.5) | |||

| Never hospitalized | 35 | 4.2 (1.0) | 0.2 | 25 | 15.3 (1.9) | 0.003 | 25 | 15.7 (2.2) | 0.0007 |

| Ever hospitalized | 38 | 4.5 (1.2) | 29 | 17.8 (3.8) | 28 | 18.4 (3.2) | |||

| WHO stage I/II | 42 | 4.1 (1.1) | 0.06 | 31 | 15.6 (2.6) | 0.01 | 30 | 16.1 (2.6) | 0.005 |

| III/IV | 29 | 4.6 (1.1) | 21 | 17.9 (3.8) | 21 | 18.5 (3.3) | |||

| CD4% ≥20% | 31 | 4.5 (1.4) | 0.2 | 22 | 17.7 (3.6) | 0.06 | 22 | 17.2 (3.3) | 0.9 |

| <20% | 42 | 4.2 (0.9) | 32 | 15.9 (3.6) | 31 | 17.1 (3.0) | |||

| CD4 count ≥ 1500 cells/mm3 | 24 | 4.1 (1.3) | 0.3 | 17 | 15.3 (2.6) | 0.04 | 17 | 15.9 (2.5) | 0.04 |

| <1500 cells/mm3 | 49 | 4.4 (1.0) | 37 | 17.3 (3.4) | 36 | 17.7 (3.2) | |||

| Plasma HIV RNA | |||||||||

| <6 log10 copies/mm3 | 20 | 4.0 (0.8) | 0.2 | 12 | 15.6 (1.6) | 0.3 | 12 | 15.7 (2.5) | 0.07 |

| ≥6 log10 copies/mm3 | 47 | 4.5 (1.3) | 37 | 16.8 (3.5) | 36 | 17.4 (2.8) | |||

| WAZ ≥−2 | 37 | 4.0 (1.0) | 0.008 | 27 | 15.1 (2.3) | 0.0003 | 27 | 15.6 (2.4) | 0.0001 |

| <−2 | 36 | 4.7 (1.1) | 27 | 18.2 (3.5) | 26 | 18.7 (2.9) | |||

| HAZ ≥−2 | 39 | 4.1 (1.1) | 0.03 | 29 | 15.6 (2.5) | 0.01 | 28 | 16.1 (2.8) | 0.009 |

| <−2 | 34 | 4.7 (1.1) | 25 | 17.8 (3.7) | 25 | 18.3 (3.0) | |||

| WHZ ≥−2 | 59 | 4.3 (1.1) | 0.2 | 45 | 16.1 (3.0) | 0.007 | 45 | 16.7 (3.1) | 0.01 |

| <−2 | 14 | 4.7 (1.1) | 9 | 19.3 (3.6) | 8 | 19.6 (1.7) | |||

| HCZ ≥−2 | 64 | 4.4 (1.2) | 0.8 | 47 | 16.5 (3.4) | 0.4 | 46 | 16.8 (3.0) | 0.08 |

| <−2 | 9 | 4.3 (0.8) | 7 | 17.7 (1.8) | 7 | 19.0 (2.9) | |||

| Maternal CD4 ≥200 cells/mm3 | 56 | 4.3 (1.2) | 0.4 | 38 | 16.1 (3.1) | 0.06 | 38 | 16.5 (2.8) | 0.04 |

| <200 cells/mm3 | 14 | 4.6 (1.1) | 14 | 18.1 (3.7) | 13 | 18.6 (3.4) | |||

Other correlates evaluated included gender, birth weight, ever breastfed, and education level of primary caregiver; results were not significant (P ≥ 0.2).

ART, antiretroviral therapy; PMTCT, prevention of mother to child transmission; WAZ, weight-for-age z-score; HAZ, height-for-age z-score; WHZ, weight-for-height z-score; HCZ, head circumference-for-age z-score.

The median ages at walking and speech were 16.1 months (IQR, 14.3, 18.8) and 16.6 months (IQR, 15.0, 19.6), respectively. Most infants attained walking prior to speech, and 10 of 53 infants attained walking after speech. For 11 of 53 infants, both milestones had been attained at or prior to the same visit. Later ages at walking and speech were each associated with hospitalization pre-ART (P=0.003 and P=0.0007, respectively), pre-ART WHO stage III/IV diagnosis (P=0.01 and P=0.005, respectively), infant CD4 count <1500 cells/mm3 (P=0.04 and P=0.04, respectively). Later ages at walking and speech achievement were also significantly associated with pre-ART WAZ <−2 (P=0.0003, P=0.0001, respectively), HAZ <−2 (P=0.01, P=0.009, respectively) and WHZ <−2 (P=0.007, P=0.01, respectively). Later speech was significantly associated with maternal CD4 count <200 cells/mm3 (P=0.04) (Table 2).

Change in Growth and Clinical Status Following Initiation of ART

Sixty-nine of 73 (94.5%) infants with data for neck control initiated ART at a median of 14 days (IQR, 7, 20) after enrollment. The median age at ART was 4.1 months (IQR, 3.5, 4.7). At 6 months post-ART, virologic and immunologic parameters were improved (data not shown), with a median plasma HIV RNA level of 3.0 log10 copies/mm3 (IQR, 2.5, 5.0) (P <0.0001) and median CD4% of 25% (IQR, 21, 31); (P <0.0001). Growth parameters increased to a median of −1.3 (IQR, −2.0, −0.6) for WAZ (P=0.02); and a median of 0.03 (IQR, −0.5, 0.8) for HCZ (P=0.007); however HAZ (median, −1.7, IQR, −2.0, −1.4) and WHZ (median, −0.6, IQR, −0.8, 0.02) did not change (P=0.3 and P=0.8, respectively).

ART Regimen and Age at Milestone Attainment

Twenty (37%) infants initiated a lopinavir/ritonavir-based ART regimen, based on prior exposure to nevirapine-PMTCT. Infants who initiated a lopinavir/ritonavir-based regimen were virologically and immunologically similar to those who initiated a nevirapine-based regimen (see Table, Supplemental Digital Content 1, which compares participants by regimen); however they were less likely to have been hospitalized before enrollment (P=0.04). These infants had earlier speech (mean, 15.5 months; SD, 1.9) compared with infants who had initiated nevirapine-based ART (mean, 18.1; SD, 3.2) (P=0.003) (Table 3). This association was not explained by differences in viral responses between infants receiving lopinavir/ritonavir- vs nevirapine-based ART. In multivariate linear regression, adjusted for 6-month virus level, mean age at speech in infants receiving lopinavir/ritonavir-based ART was 2.59 months (95% CI, 1.03, 4.15) earlier than for infants on nevirapine-based ART (P=0.002). The association between age at speech and ART regimen also remained when adjusted WHO stage III/IV diagnosis, hospitalization prior to enrollment, and pre-ART WAZ, HAZ, and WHZ. ART regimen was not associated with age at walking.

TABLE 3.

Post-ART correlates of age at milestone attainment

| Correlate | N | Mean (SD) age at walking | P-value | N | Mean (SD) age at speech | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initiated on LPV/r-ART | 20 | 16.4 (2.7) | 0.7 | 20 | 15.5 (1.9) | 0.003* |

| NVP-ART | 34 | 16.8 (3.6) | 33 | 18.1 (3.2) | ||

| 6-month CD4% ≥20 | 42 | 16.0 (2.7) | 0.008 | 41 | 16.6 (2.9) | 0.03 |

| <20 | 12 | 18.8 (4.2) | 12 | 18.8 (2.9) | ||

| 6-month CD4 count ≥ 1500 cells/mm3 | 38 | 16.1 (2.8) | 0.06 | 38 | 16.8 (3.1) | 0.2 |

| <1500 cells/mm3 | 16 | 18.0 (3.9) | 15 | 18.1 (2.9) | ||

| 6-month Plasma HIV RNA <1000 copies/mm3 | 29 | 16.2 (3.1) | 0.3 | 29 | 16.5 (3.1) | 0.1 |

| ≥1000 copies/mm3 | 25 | 17.2 (3.5) | 24 | 17.8 (2.9) | ||

| 6-month WAZ ≥−2 | 40 | 15.7 (2.4) | 0.0003 | 39 | 16.5 (2.6) | 0.009 |

| <−2 | 14 | 19.2 (4.1) | 14 | 18.9 (3.6) | ||

| 6-month HAZ ≥−2 | 34 | 15.9 (2.9) | 0.02 | 33 | 16.3 (2.8) | 0.009 |

| <−2 | 20 | 18.0 (3.5) | 20 | 18.5 (3.1) | ||

| 6-month WHZ ≥−2 | 47 | 16.2 (2.9) | 0.006 | 46 | 16.9 (3.0) | 0.3 |

| <−2 | 7 | 19.8 (4.3) | 7 | 18.3 (3.2) | ||

| 6-month HCZ ≥−2 | 50 | 16.6 (3.3) | 1.0 | 49 | 17.1 (3.1) | 0.9 |

| <−2 | 3 | 16.6 (1.2) | 3 | 17.4 (4.2) | ||

| Neck control at age <4 months | 21 | 15.2 (2.7) | 0.007 | 21 | 16.2 (3.0) | 0.07 |

| ≥4 months | 33 | 17.6 (3.3) | 32 | 17.7 (3.0) | ||

| Neck control at age <4 months† | 7 | 15.2 (3.4) | 0.06 | 7 | 17.4 (3.9) | 1.0 |

| ≥4 months | 23 | 18.1 (3.3) | 22 | 17.4 (2.6) |

In multivariate linear regression analyses adjusted for 6-month plasma HIV RNA level, infants who initiated LPV/r-ART had earlier speech (adj. regression coefficient, −2.58 months (95% confidence interval, −4.14, −1.02) (P=0.002) compared with infants with NVP-ART.

Excludes infants who had achieved neck control prior to enrollment.

ART, antiretroviral therapy; LPV/r, lopinavir-boosted-ritonavir; WAZ, weight-for-age z-score; HAZ, height-for-age z-score; WHZ, weight-for-height z-score; HCZ, head circumference-for-age z-score.

Response to ART and Age at Milestone Attainment

We examined the relationship between immunologic, virologic and growth responses during the first 6 months of ART, and initiation of speech and walking. Later ages at walking and speech attainment were each associated with 6-month CD4% <20% (P=0.008 and P=0.03) (Table 3). In analyses adjusted for pre-ART CD4%, walking occurred 0.18 months earlier (P=0.004) and speech occurred 0.12 months earlier (P=0.05) for each one-unit increase in CD4% gain (Table 4). There was a trend for later speech in infants who had a 6-month plasma HIV RNA ≥ 1000 copies/mm3 (mean, 16.5 months (SD, 3.1) vs. mean, 17.8 months (SD, 2.9); P=0.1). There was no relation between age at walking and 6-month virologic response.

TABLE 4.

Relation between the change in pre-ART to 6-month post-ART immune, viral, and growth parameters and age at walking and speech

| Walking (N=54) | Speech (N=53) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Change from pre-ART to 6 months post-ART | RC (95% CI) (P-value) | Adj. RC (95% CI) (P-value) | RC (95% CI) (P-value) | Adj. RC (95% CI) (P-value) |

| CD4%, per unit increase | −0.14 (−0.24, −0.04) (0.006) | −0.18 (−0.30, −0.06) (0.004) | −0.06 (−0.16, 0.04) (0.2) | −0.12 (−0.23, −0.003) (0.05) |

| Plasma HIV RNA per log10 copies/mm3 increase* | 0.17 (−0.45, 0.79) (0.6) | 0.29 (−0.38, 0.95) (0.4) | 0.23 (−0.34, 0.82) (0.4) | 0.52 (−0.06, 1.10) (0.08) |

| WAZ, per SD increase | 0.16 (−0.46, 0.78) (0.6) | −0.94 (−1.64, −0.24) (0.009) | 0.48 (−0.09, 1.05) (0.09) | −0.29 (−0.98, 0.40) (0.4) |

| HAZ, per SD increase | 0.14 (−0.74, 1.03) (0.7) | −1.34 (−2.54, −0.14) (0.03) | 0.53 (−0.29, 1.35) (0.2) | −.85 (−1.95, 0.25) (0.1) |

| WHZ, per SD increase | −0.003 (−0.58, 0.57) (1.0) | −0.79 (−1.46, −0.12) (0.02) | 0.14 (−0.40, 0.69) (0.6) | −0.20 (−0.88, 0.48) (0.6) |

| HCZ, per SD increase* | −0.30 (−1.23, 0.63) (0.5) | −0.98 (−2.14, 0.19) (0.1) | 0.7 (−0.17, 1.58) (0.1) | 0.48 (−0.64, 1.60) (0.4) |

N=49 for analysis of HIV RNA and walking and N=48 for analysis of HIV RNA and speech; N=52 for analysis of HCZ and speech.

RC, regression coefficient; CI, confidence interval; SD, standard deviation; WAZ, weight-for-age z-score; HAZ, height-forage z-score; WHZ, weight-for-height z-score; HCZ, head circumference-for-age z-score.

Infants who were underweight, stunted, or wasted at 6 months post-ART had significantly later walking (P=0.0003, P=0.02 and P=0.006, respectively). Infants who were underweight or stunted also had significantly later speech (P=0.009 and P=0.009, respectively). Adjusted for baseline pre-ART z-scores, infants with smaller 6-month gains in WAZ, HAZ, and WHZ had later walking (0.94 months later per WAZ unit; P=0.009, 1.34 months later per HAZ unit; P=0.03, 0.79 months later per WHZ unit; P=0.02, and 0.98 months later per HCZ unit; P=0.1). There was a trend towards later speech for infants with smaller 6-month increase in HAZ (0.85 months later per HAZ unit; P=0.1). Considering that the regression coefficients and P-values for the relationship between 6-month change in growth parameters and age at walking differed substantially between unadjusted and adjusted models (Table 4), we explored potential interaction between pre-ART levels and the magnitude of 6-month change for WAZ, HAZ, and WHZ. In these analyses, there was no indication of interaction (all P-values >0.3).

We examined whether infants with later neck control also had later walking and speech. Infants with later neck control had later walking (P=0.007; Table 3). In a separate model excluding infants who already had neck control at enrollment (N=31) and including infants who attained neck control during follow-up (N=42), infants with neck control at age ≥ 4 months had a trend towards later walking (P=0.06).

DISCUSSION

In this cohort of ART-treated infants who began treatment at <5 months of age, the median ages of neck control, unsupported walking and monosyllabic speech attainment were 4.4, 16.0, and 16.6 months, respectively. Initiation of a non-PI-based regimen, advanced HIV disease stage and poor growth prior to ART, and poor immune and growth response to ART were associated with later milestone attainment.

We found that infants who received lopinavir/ritonavir-based ART had earlier speech than infants who received nevirapine-based ART. In 91 children ≤ 3 years of age, switch to a PI-based regimen provided a modest benefit in cognitive scores.25 These observations may be explained by improved viral response to PI-based ART, as has been demonstrated in randomized clinical trials of lopinavir/ritonavir- vs. nevirapine-based ART in children.33,34 However, when adjusting for 6-month HIV virus level in our study, the association between lopinavir/ritonavir-based ART and initiation of speech was significant, suggesting this relationship is not wholly explained by lower plasma virus levels. Alternatively, lopinavir/ritonavir-based ART may have improved viral or immune responses within the CNS, although both nevirapine and lopinavir/ritonavir are considered to have high penetration into the CNS, with nevirapine ranked higher.35 A third possibility is that improved developmental outcomes in infants who received lopinavir/ritonavir-based ART reflects receipt of PMTCT, a potential proxy for better health-care access or maternal health seeking behaviors. However, in analyses adjusted for cofactors related to HIV disease and malnutrition, the association between PI-regimen and age at speech remained.

It is intriguing that ART regimen was associated with age at speech, but not walking, suggesting effects on specific domains of development. Delays in expressive rather than receptive language, and not in cognitive ability have been reported in children with limited ART.36 High plasma HIV RNA, immunosuppression, and advanced HIV disease were each associated with impaired language in school-age treated HIV-infected children with a concurrent cognitive or hearing impairment.21 In utero exposure to atazanavir was associated with impaired language; however neither nevirapine nor lopinavir/ritonavir were associated language ability in this study.37 Other studies have not found that fetal exposure to antiretrovirals is associated with risk of neurodevelopmental outcomes.38

We found that infants with a previous hospitalization, a WHO stage III/IV diagnosis, a lower pre-ART CD4 count, and lower maternal CD4 count had later age at attainment of milestones. These data are consistent with previous studies of HIV-infected infants, which also found that lower neurocognitive test scores are associated with cofactors for increased HIV disease severity, including in utero HIV acquisition,13 an AIDS diagnosis,6,25,39,40 and high plasma virus level.11,18 These data further confirm that early diagnosis and ART prior to onset of symptomatic HIV disease is critical.

Poorer immune status following 6 months of ART was significantly associated with later walking and speech, and there was a trend for poor viral suppression at 6-months and later speech. Infants with a higher magnitude of CD4% increase following ART had earlier milestone attainment, independent of pre-ART CD4%. These data suggest that in addition to pre-ART viral and immune status, immune reconstitution and viral suppression post-ART are important to optimize developmental outcomes in infants.

One distinctive feature of infants in this study is the severity of their HIV disease and poor growth prior to ART, both of which were associated with later milestone attainment. Reduced growth reconstitution following ART also correlated with later walking. Delays in milestone attainment may be partly attributable to poor nutritional status, exacerbated by poverty, the metabolic cost of HIV, and poor maternal health. At 6 months post-ART, HIV-infected infants in our cohort had substantially lower mean z-scores for weight (−1.4; standard deviation (SD), 1.3), height (−1.9; SD, 1.1), and weight-for-height (−0.6; SD, 1.4) than the national averages for 9–11 month old Kenyan infants (means, −0.6 (WAZ), −1.1 (HAZ), and 0.0 (WHZ), respectively).41

Whether HIV-infected children with access to ART from infancy will have long-term neurocognitive compromise is unclear. It is encouraging that infants in the CHER early ART arm and who initiated ART while still asymptomatic and at a median age of 2 months had similar psychomotor scores at one year of age compared with HIV-uninfected children.26 Infants with deferred ART in CHER had lower scores. In our study, many infants were symptomatic and also initiated ART at ages later than in the CHER early ART arm. Data are limited for long-term neurocognitive outcomes in US/European children because these cohorts had heterogeneous ART histories reflecting the evolution of combination ART during the mid- and late 1990s. It will be important to monitor HIV-infected children in sub-Saharan Africa with access to early infant ART, particularly those who have risk factors for neurocognitive delays. These children could be targeted for clinic-based42 or simple home-based interventions.43

Strengths of our study are inclusion of infants who received empiric ART, the availability of detailed immune, viral, and anthropometric data, and use of either lopinavir/ritonavir- or nevirapine-based ART. In CHER, all infants received lopinavir/ritonavir-based ART. The cohort is relevant for many settings in sub-Saharan Africa because HIV-diagnosis typically occurs after symptomatic HIV disease. The simplicity of the methods described here afforded practicality for a busy clinic, and monthly prospective data collection.

Limitations of the study include the relatively small sample size and high early attrition due to mortality, which may have attenuated our ability to detect some cofactors for milestone attainment. The developmental assessment described here involved minimal training and is less comprehensive than others.14,25,26 Due to the observational study design, it is difficult to infer an association between ART regimen and age at speech. Few infants had in utero exposure to antiretrovirals, limiting our ability to examine this potential cofactor. Premature birth was not systematically assessed, and we were unable to adjust analyses for prematurity, a key potential confounder for the relationships between slower immune and growth recovery and later age at milestone attainment. Age of neck control may have been overestimated in infants enrolled after having established neck control.

In summary, HIV disease progression, poor growth, and poor response to ART were associated with later age of achievement of milestones in HIV-infected infants. The association between lopinavir/ritonavir-based ART and age at speech milestone warrants further study. It remains important to optimize ART responses in order to enhance developmental outcomes in HIV-infected children.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest or funding to disclose. The Optimizing HIV-1 Therapy Study was supported by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) grant 2 R01 HD023412. Field site and biostatistical support were provided by the University of Washington Center for AIDS Research International Core, an NIH funded program (P30 AI027757) which is supported by the following NIH Institutes and Centers (NIAID, NCI, NIMH, NIDA, NICHD, NHLBI, NCCAM). SBN was supported by 2 R01 HD023412 and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) grant 5K01NS080637. DW was supported by the Global Research Initiative Program, Social Science (R01 TW007632). GJS was supported by NIH grant K24 HD054314.

We thank Jennifer Slyker and Barbara Richardson for assistance and insightful discussions during development of this manuscript. We thank the Kenya Research Program, Kizazi working group, and the UW Global Center for Integrated Health of Women, Adolescents and Children (Global WACh) for their support during the preparation of this article. Thank you to the OPH administrative, clinic, and data management staff in Nairobi, Kenya, and in Seattle, Washington for their ongoing support, commitment, and participation. We are grateful to the OPH Study participants, without whom this research would not be possible.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None of the authors have financial interests or conflicts of interest relevant to this study.

Data presented at the 3rd International Workshop on HIV Pediatrics, Rome, Italy, July 2011.

References

- 1.Violari A, Cotton MF, Gibb DM, et al. Early antiretroviral therapy and mortality among HIV-infected infants. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(21):2233–2244. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0800971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wachsler-Felder JL, Golden CJ. Neuropsychological consequences of HIV in children: a review of current literature. Clin Psychol Rev. 2002;22(3):443–464. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(01)00108-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tardieu M. HIV-1 and the developing central nervous system. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1998;40(12):843–846. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Drotar D, Olness K, Wiznitzer M, et al. Neurodevelopmental outcomes of Ugandan infants with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. Pediatrics. 1997;100(1):E5. doi: 10.1542/peds.100.1.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gay CL, Armstrong FD, Cohen D, et al. The effects of HIV on cognitive and motor development in children born to HIV-seropositive women with no reported drug use: birth to 24 months. Pediatrics. 1995;96(6):1078–1082. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nozyce M, Hittelman J, Muenz L, et al. Effect of perinatally acquired human immunodeficiency virus infection on neurodevelopment in children during the first two years of life. Pediatrics. 1994;94(6 Pt 1):883–891. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Msellati P, Lepage P, Hitimana DG, et al. Neurodevelopmental testing of children born to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 seropositive and seronegative mothers: a prospective cohort study in Kigali, Rwanda. Pediatrics. 1993;92(6):843–848. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gonzalez-Scarano F, Martin-Garcia J. The neuropathogenesis of AIDS. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5(1):69–81. doi: 10.1038/nri1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sei S, Stewart SK, Farley M, et al. Evaluation of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) type 1 RNA levels in cerebrospinal fluid and viral resistance to zidovudine in children with HIV encephalopathy. J Infect Dis. 1996;174(6):1200–1206. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.6.1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tardieu M, Le Chenadec J, Persoz A, et al. HIV-1-related encephalopathy in infants compared with children and adults. French Pediatric HIV Infection Study and the SEROCO Group. Neurology. 2000;54(5):1089–1095. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.5.1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pollack H, Kuchuk A, Cowan L, et al. Neurodevelopment, growth, and viral load in HIV-infected infants. Brain Behav Immun. 1996;10(3):298–312. doi: 10.1006/brbi.1996.0026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McGrath N, Fawzi WW, Bellinger D, et al. The timing of mother-to-child transmission of human immunodeficiency virus infection and the neurodevelopment of children in Tanzania. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006;25(1):47–52. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000195638.80578.e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith R, Malee K, Charurat M, et al. Timing of perinatal human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection and rate of neurodevelopment. The Women and Infant Transmission Study Group. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2000;19(9):862–871. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200009000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chase C, Ware J, Hittelman J, et al. Early cognitive and motor development among infants born to women infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Women and Infants Transmission Study Group. Pediatrics. 2000;106(2):E25. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.2.e25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bagenda D, Nassali A, Kalyesubula I, et al. Health, neurologic, and cognitive status of HIV-infected, long-surviving, and antiretroviral-naive Ugandan children. Pediatrics. 2006;117(3):729–740. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dollfus C, Le Chenadec J, Faye A, et al. Long-term outcomes in adolescents perinatally infected with HIV-1 and followed up since birth in the French perinatal cohort (EPF/ANRS CO10) Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51(2):214–224. doi: 10.1086/653674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patel K, Ming X, Williams PL, et al. Impact of HAART and CNS-penetrating antiretroviral regimens on HIV encephalopathy among perinatally infected children and adolescents. Aids. 2009;23(14):1893–1901. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832dc041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chiriboga CA, Fleishman S, Champion S, et al. Incidence and prevalence of HIV encephalopathy in children with HIV infection receiving highly active anti-retroviral therapy (HAART) J Pediatr. 2005;146(3):402–407. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wood SM, Shah SS, Steenhoff AP, et al. The impact of AIDS diagnoses on long-term neurocognitive and psychiatric outcomes of surviving adolescents with perinatally acquired HIV. Aids. 2009;23(14):1859–1865. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832d924f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nozyce ML, Lee SS, Wiznia A, et al. A behavioral and cognitive profile of clinically stable HIV-infected children. Pediatrics. 2006;117(3):763–770. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rice ML, Buchanan AL, Siberry GK, et al. Language impairment in children perinatally infected with HIV compared to children who were HIV-exposed and uninfected. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2012;33(2):112–123. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e318241ed23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coplan J, Contello KA, Cunningham CK, et al. Early language development in children exposed to or infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Pediatrics. 1998;102(1):e8. doi: 10.1542/peds.102.1.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DeCarli C, Fugate L, Falloon J, et al. Brain growth and cognitive improvement in children with human immunodeficiency virus-induced encephalopathy after 6 months of continuous infusion zidovudine therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1991;4(6):585–592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCoig C, Castrejon MM, Castano E, et al. Effect of combination antiretroviral therapy on cerebrospinal fluid HIV RNA, HIV resistance, and clinical manifestations of encephalopathy. J Pediatr. 2002;141(1):36–44. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2002.125007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lindsey JC, Malee KM, Brouwers P, et al. Neurodevelopmental functioning in HIV-infected infants and young children before and after the introduction of protease inhibitor-based highly active antiretroviral therapy. Pediatrics. 2007;119(3):e681–693. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laughton B, Cornell M, Grove D, et al. Early antiretroviral therapy improves neurodevelopmental outcomes in infants. Aids. 2012;26(13):1685–1690. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328355d0ce. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.World Health Organization. Antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection in infants and children: towards universal access: recommendation for a public health approach - 2010 revision. Geneva: WHO; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wamalwa D, Benki-Nugent S, Langat A, et al. Survival benefit of early infant antiretroviral therapy is compromised when HIV-1 diagnosis is delayed. Pediatr Infect Dis J. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3182587796. Submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Frankenburg WK, Dodds J, Archer P, et al. The Denver II: a major revision and restandardization of the Denver Developmental Screening Test. Pediatrics. 1992;89(1):91–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chohan BH, Emery S, Wamalwa D, et al. Evaluation of a single round polymerase chain reaction assay using dried blood spots for diagnosis of HIV-1 infection in infants in an African setting. BMC Pediatr. 2011;11:18. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-11-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Emery S, Bodrug S, Richardson BA, et al. Evaluation of performance of the Gen-Probe human immunodeficiency virus type 1 viral load assay using primary subtype A, C, and D isolates from Kenya. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38(7):2688–2695. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.7.2688-2695.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.World Health Organization. WHO child growth standards: length/height-for-age, weight-for-age, weight-for-length, weight-for-height and body mass index-for-age: Methods and development. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Palumbo P, Lindsey JC, Hughes MD, et al. Antiretroviral treatment for children with peripartum nevirapine exposure. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(16):1510–1520. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Violari A, Lindsey JC, Hughes MD, et al. Nevirapine versus ritonavir-boosted lopinavir for HIV-infected children. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(25):2380–2389. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Letendre S, Marquie-Beck J, Capparelli E, et al. Validation of the CNS Penetration-Effectiveness rank for quantifying antiretroviral penetration into the central nervous system. Arch Neurol. 2008;65(1):65–70. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2007.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wolters PL, Brouwers P, Civitello L, et al. Receptive and expressive language function of children with symptomatic HIV infection and relationship with disease parameters: a longitudinal 24-month follow-up study. Aids. 1997;11(9):1135–1144. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199709000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rice ML, Zeldow B, Siberry GK, et al. Evaluation of risk for late language emergence after in utero antiretroviral drug exposure in HIV-exposed uninfected infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013;32(10):e406–413. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31829b80ee. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Williams PL, Marino M, Malee K, et al. Neurodevelopment and in utero antiretroviral exposure of HIV-exposed uninfected infants. Pediatrics. 2010;125(2):e250–260. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Belman AL, Muenz LR, Marcus JC, et al. Neurologic status of human immunodeficiency virus 1-infected infants and their controls: a prospective study from birth to 2 years. Mothers and Infants Cohort Study. Pediatrics. 1996;98(6 Pt 1):1109–1118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Abubakar A, Holding P, Newton CR, et al. The role of weight for age and disease stage in poor psychomotor outcome of HIV-infected children in Kilifi, Kenya. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2009;51(12):968–973. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2009.03333.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS) and ICF Macro. Kenya Demographic and Health Survey 2008–09. Calverton, Maryland: KNBS and ICF Macro; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Boivin MJ, Busman RA, Parikh SM, et al. A pilot study of the neuropsychological benefits of computerized cognitive rehabilitation in Ugandan children with HIV. Neuropsychology. 24(5):667–673. doi: 10.1037/a0019312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Potterton J, Stewart A, Cooper P, et al. The effect of a basic home stimulation programme on the development of young children infected with HIV. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2010;52(6):547–551. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2009.03534.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.