Abstract

Research linking childhood emotional abuse (CEA) and adult marital satisfaction has focused on individuals without sufficient attention to couple processes. Less attention has also been paid to the effects of CEA on the ability to read other’s emotions, and how this may be related to satisfaction in intimate relationships. In this study, 156 couples reported on histories of CEA, marital satisfaction and empathic accuracy of their partners’ positive and hostile emotions during discussion of conflicts in their relationships. Actor-Partner Interdependence Modeling was used to examine links between CEA and marital satisfaction, with empathic accuracy as a potential mediator. Both men’s and women’s CEA histories were linked not only with their own lower marital satisfaction but also with their partners’ lower satisfaction. Empathic accuracy for hostile emotions mediated the link between women’s CEA and their satisfaction and their partners’ satisfaction in the relationship. Findings suggest that a history of CEA is associated with difficulties with empathic accuracy, and that empathic inaccuracy in part mediates the association between CEA and adult marital dissatisfaction.

Keywords: child victimization, emotional abuse, relationship satisfaction, empathic accuracy, couples

Childhood maltreatment has been the focus of much research in recent decades, and the effects it has in adulthood are well documented (Fergusson, Boden, & Horwood, 2008). Clinical experience and empirical research point to serious interpersonal consequences of childhood maltreatment. Individuals with histories of abuse have been shown to experience more unstable and less satisfying intimate relationships than those without abuse histories (Godbout, Sabourin, & Lussier, 2009; Maneta, Cohen, Schulz, & Waldinger, 2012). Multiple explanations have been proposed to explain this link (Alexander, 2003; Finkelhor & Browne, 1985; Polusny & Follette, 1995), but the mechanisms by which childhood maltreatment influences adult relationships are incompletely understood.

Researchers have found that emotional maltreatment of children – that is, belittling, degrading, intimidating behaviors by caregivers directed towards children – is common (DiLillo & Long, 1999; Wright, Crawford, & Del Castillo, 2009) and is associated with negative interpersonal sequelae in adulthood (Wright, 2007). According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2013), 57,880 U.S. children experienced emotional abuse in 2012. Childhood emotional abuse often co-occurs with sexual and/or physical abuse (Wright et al., 2009); however, emotional abuse may be more detrimental when compared to these other forms of abuse because it is usually more pervasive (Wright, 2007). One hypothesis explaining the link between emotional abuse and later interpersonal difficulties is that emotional abuse may hamper children’s ability to express their own emotions clearly and to read others’ emotions accurately. These difficulties can result in problems in intimate relationships later in life. The purpose of this study is to examine the association between histories of childhood emotional abuse and current satisfaction with adult intimate relationships and to test whether the ability to accurately read a partner’s negative emotions mediates this link.

Emotional Abuse and Marital Satisfaction

Most studies on childhood maltreatment have focused on the effects of physical and sexual abuse, but accumulating research links childhood emotional abuse (also referred to as psychological maltreatment) with negative psychological and social sequelae in adulthood (Wright et al., 2009). Briere and Rickards (2007) examined 620 individuals and found that exposure to emotional abuse during childhood was associated with interpersonal conflict and concerns about abandonment. Childhood emotional abuse has also been shown to be the strongest predictor of adult emotion dysregulation compared to other forms of abuse (Burns, Jackson, & Harding, 2010).

Clinical observations and research evidence also converge in documenting the detrimental effects of childhood emotional abuse on later functioning in intimate relationships. Perry and colleagues (Perry, DiLillo, & Peugh, 2007) found an association between a history of childhood psychological maltreatment and marital satisfaction in newlywed couples. DiLillo and colleagues (2009) measured the links between childhood maltreatment and marital satisfaction over a 2-year period in a large sample of couples and found that childhood emotional abuse was associated with lower marital satisfaction concurrently and during follow-up assessments. In addition, they found an association between childhood emotional abuse and lower marital trust. Difficulties with trust within an intimate relationship have been associated with both childhood maltreatment and marital dissatisfaction (DiLillo & Long, 1999). Bradbury and Shaffer (2012) also identified associations between childhood emotional abuse and adult relationship satisfaction and found that emotion regulation difficulties resulting from exposure to emotional abuse, including difficulties with emotional awareness, mediated this link.

To date, theoretical frameworks used to explain why victims of childhood abuse have interpersonal difficulties have focused primarily on intra-psychic changes, such as disrupted attachment, shame, feelings of betrayal, and loss of trust that result from early maltreatment. For example, Messman-Moore and Coates (2007) found that the link between childhood psychological maltreatment and conflict in adult relationships among 382 college women was partly explained by maladaptive internalized schemas that created strong sensitivity to violations of trust, abandonment and experiences of shame. At the same time, there is evidence to suggest that childhood abuse not only leads to alterations in the way the self is perceived (e.g., shame about one’s behavior) but also affects one’s perceptions of others and their behavior (Waldinger, Toth, & Gerber, 2001). Distortions in the perception of both self and others have important implications for the development of empathic understanding in intimate relationships.

Emotional Abuse and Empathic Accuracy

One of the most robust correlates of childhood emotional abuse is a negative cognitive attributional style (Gibb, 2002; Rose & Abramson, 1992), which can impair one’s ability to read other’s emotions accurately and lead to misperceptions of affectively salient behaviors and events. Attributions stem from our attempts to understand the causes of events (Heider, 1958), and early maltreatment has been shown to influence one’s attributional style (Buser & Hackney, 2012; Chen, Coccaro, Lee, & Jacobson, 2012). Research to date has focused on the effects of childhood emotional abuse on negative cognitive styles mostly as they pertain to deleterious evaluations about oneself (Gibb & Abela, 2008). Little attention has been paid, however, to how childhood emotional abuse may impact the way individuals perceive others’ emotions and emotionally salient behaviors, particularly in the context of challenging interactions.

Attributions about the other in interpersonal relationships have been linked with one’s empathic accuracy (Schweinle, Ickes, & Bernstein, 2002; Sillars, Smith, & Koerner, 2010). Misperceptions stemming from histories of childhood emotional abuse are likely to limit individuals’ ability to accurately read their partners’ emotions. Misreading may be particularly likely and consequential during emotionally charged moments (Carrére, Buehlman, Gottman, Coan, & Ruckstuhl, 2000; Waldinger & Schulz, 2006), making the resolution of tensions between partners even more challenging.

Exposure to emotional abuse may also affect individuals’ awareness of their own emotions (Bradbury & Shaffer, 2012) and make it harder to acknowledge and express their emotional state. This can, in turn, affect empathic accuracy as empathy is a two-way or dyadic process that depends not only on one’s ability to read the other’s emotions but also on the other’s ability to appropriately express emotions (Zaki, Bolger, & Ochsner, 2008).

Empathic Accuracy and Marital Satisfaction

The ability of partners to read each other’s emotions accurately has been shown to have implications for their satisfaction within the relationship (Ickes & Simpson, 1997, 2001). Some research has shown that empathic accuracy particularly for a partner’s negative emotions may adversly affect the perceiver’s marital satisfaction (Kilpatrick, Bissonnette, & Rusbult, 2002; Simpson, Oriña, & Ickes, 2003). However, a more recent study by Cohen and colleagues (2012) found different patterns of connections for men and women; women’s empathic accuracy for their partners’ negative emotions was significantly and positively linked with their marital satisfaction, whereas men’s empathic accuracy for their partners’ negative emotions was not associated with their own marital satisfaction. This study also found that men’s and women’s ability to read their partners’ negative emotions accurately was associated with their partners reporting greater marital satisfaction, highlighting the importance of dyadic influences when considering empathic accuracy. Such dyadic effects are also critically important when addressing the influence of partners’ histories of abuse on the relationship and can be captured by using an Actor-Partner Interdependence Model (APIM), a form of structural equation modeling (Kashy, Kenny, Reis, & Judd, 2000). By employing this data-analytic and conceptual framework we simultaneously account for the histories of emotional abuse and current marital satisfaction for both partners, and can differentiate between actor effects (links between one’s own abuse history and one’s current marital satisfaction) and partner effects (links between one’s own abuse history and a partner’s marital satisfaction). We can therefore answer questions such as: ―How is one’s experience of childhood emotional abuse linked with their relationship satisfaction (actor effect) and with their partner’s satisfaction (partner effect)?” Mediation analyses within the APIM framework can then examine whether that link can in part be explained by the ability to read a partner’s negative emotions accurately.

Current Study

Based on prior theory and research, we hypothesized that severity of childhood emotional abuse would be linked with both one’s own and one’s partner’s lower marital satisfaction (i.e., have both actor and partner effects). We also predicted that childhood emotional abuse histories would be linked with one’s ability to read their partner’s emotions accurately. Finally, we predicted that empathic accuracy would mediate the association between histories of emotional abuse and marital satisfaction.

In the present study, we examined the associations between reported severity of childhood emotional abuse and one’s own and one’s partner’s marital satisfaction using the APIM (Kashy et al., 2000), which takes into account both individual and dyadic influences simultaneously. We extended the basic APIM by examining whether accuracy in reading partners’ emotions mediated those associations. Using a dyadic approach is particularly important when assessing marital satisfaction as previous research has already demonstrated that individuals’ characteristics can have effects not only on their own satisfaction but also on their partners’ satisfaction (Whisman, Uebelacker, & Weinstock, 2004). By simultaneously examining both actor and partner effects, we can narrow the range of possible mechanisms that might account for the influence of childhood emotional abuse on couples’ marital satisfaction. For example, weak actor effects and strong partner effects would suggest that being understood by a partner is more critical to one’s own marital satisfaction whereas weak partner effects and strong actor effects might suggest that understanding a partner is a critical influence on one’s own marital satisfaction.

Methods

Participants

One hundred and fifty six couples were recruited in the greater Boston, Massachusetts, and Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania, areas to participate in a study about intimate relationships (for details, see Waldinger & Schulz, 2006). The sample was community-based and was recruited in the two locations using complementary strategies to obtain participants with a wide range of marital quality and to oversample individuals with histories of childhood abuse. In Boston (n = 102), recruitment focused on younger, urban, and ethnically and socioeconomically diverse couples in committed relationships (i.e., married for any length of time, or living together for a minimum of 12 months). In Bryn Mawr (n = 54), recruitment focused on older, suburban, middle-class married couples with strong ties to the community (see Waldinger & Schulz, 2006). The mean age for men was 38.3 years (SD = 10.2) and for women 36.2 years (SD = 8.8). The median length of relationship for the couples was 3.5 years (range 0.4 – 30.0), 56% were married, and 43% had children. Ethnicity of the sample was 71% Caucasian, 19% African American, 6% Hispanic, and 4% other. The median family income per year was between $50,000 and $65,000 and 31% had a high-school education or less.

Procedure

The research protocol for this study was approved by the Human Subjects Review Committees at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA, and Bryn Mawr College, Bryn Mawr, PA. After providing written informed consent, participants at both study sites completed questionnaires prior to participating in a laboratory couple interaction task and video recall procedure. To prepare for the interaction task, participants were asked independently of their partners to recall and describe an incident within the past two months in which their partners frustrated, disappointed, angered, or upset them. The couple was then brought together and asked to discuss an incident described by each partner while being videotaped. After the discussion, participants were shown a videotape of their interactions and used an electronic rating device designed for this study to rate how negatively or positively they felt at each moment of the interaction (for details, see Cohen et al., 2012; Schulz & Waldinger, 2004).

Participants’ ratings of their feelings from this first phase of the video recall procedure were then used to identify six high affect moments (HAMs) for each couple. These included the two 30-second segments from each discussion identified by each partner as most emotionally negative, yielding a total of four negative HAMs (two rated as most negative by her and two by him) as well as the 30-second segment rated as most positive by each partner, yielding two positive HAMs for the couple. In the second phase of the video recall task, participants watched the six HAMs in order of occurrence during the discussion. After viewing each HAM, participants completed questionnaires asking about the specific feelings they and their partner experienced during the segments.

Measures

Childhood trauma

Histories of childhood trauma were assessed using the 28-item Short Form of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ; Bernstein et al., 1994). Items on the CTQ ask about experiences of sexual abuse, physical abuse, emotional abuse, physical neglect, and emotional neglect in childhood and adolescence and are rated on a 5-point, Likert-type scale with response options ranging from Never True (1) to Very Often True (5). The CTQ has been shown to yield reliable and valid retrospective assessments of childhood abuse and neglect (Bernstein et al., 1994). The CTQ subscale score for emotional abuse (α for men = .82, for women .89) was used in our analyses. Emotional abuse was defined as “verbal assaults on a child’s sense of worth or well-being or any humiliating or demeaning behavior directed toward a child by an adult or older person” (Bernstein et al., 1994). Childhood emotional abuse scores ranged from 5 (no emotional abuse at all) to 23 (extensive emotional abuse, 25 is the maximum score) for men with a mean of 9.4 (SD = 4.6). The range for women was from 5 to 25 with a mean of 12.2 (SD = 5.9). Of all the participants, 12.2% of women and 21.2% of men reported no emotional abuse. Boston couples reported higher levels of emotional abuse (M = 10.3, SD = 5) compared to Bryn Mawr couples (M = 7.8, SD = 2.8), t = 3.9, p < 0.001. Given the skewed distribution of the emotional abuse data, primary analyses were followed by bootstrapping analyses that are more robust with data that departs from normality (Cheung & Lau, 2008; Delucchi & Bostrom, 2004; Shrout & Bolger, 2002).

Relationship satisfaction

The Locke–Wallace Marital Adjustment Test—Short Form (SMAT; Locke & Wallace, 1987) was used to measure relationship satisfaction. The SMAT is a 15-item self-report measure with scores ranging from 2 to 158 (responses are weighed differently Locke & Wallace, 1959), and it assesses overall adjustment and happiness within the relationship, conflict resolution, disagreements, cohesion, and communication. The measure has demonstrated good internal reliability, test–retest stability, and discriminant validity (Freeston & Plechaty, 1997). In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha for men was 0.7, and for women it was 0.76. Men’s mean level of satisfaction was 106.6 (SD = 28.1) and women’s was 106.1 (SD = 29.4) on the SMAT. A significant proportion of the overall sample (38%) reported satisfaction scores in the clinically distressed range (a score lower than 100 is the traditional cut-off point for marital maladjustment; (Gottman, 1994). There was a high degree of correlation between husbands’ and wives’ relationship satisfaction scores (r = .62, p <. 001). As expected, couples in Boston were significantly less satisfied with their relationships (M = 100.1, SD = 29.5) compared to couples in Bryn Mawr (M = 117.2, SD = 25.9), t = −3.6, p < 0.001.

Self- and partner-reported hostile and positive affect

The HAM emotion questionnaire includes16 emotions that people may experience during couple interactions (angry, irritated, happy, sad, guilty, ashamed, close to my partner, supported, afraid, nervous, disgusted, upset, jittery, hurt, critical, and defensive). Using a scale from one to seven (1 = not at all and 7 = very much), participants were asked to rate how much they were feeling each of the emotions during each of the six HAMs. Two factor-analytically derived scales were used in this study (see (Schulz & Waldinger, 2004; Waldinger & Schulz, 2006). The Hostile scale consisted of the following emotion states: angry, irritated, disgusted, upset, hurt, critical, and defensive. The Positive scale included: happy, close and supported. Good internal reliability (alpha coefficients ranged from .74 to .80) was found for both scales (Schulz & Waldinger, 2004). The third subscale of the HAM, the Sad/Vulnerable subscale was not used in analyses due to the fact that it did not correlate with the outcome measure. Participants also rated their partners’ emotions during each of the six HAMs, yielding partner perceptions of hostile and positive affect.

Empathic accuracy

The accuracy with which partners read each other’s emotions was operationalized as the correlation between spouses’ report of their own emotions and partners’ perception of their spouses’ emotions on the HAM questionnaire. Empathic accuracy correlations were calculated separately for hostile (men’s scores ranged from −0.41 to 0.82, M = 0.26, SD = 0.26; women’s scores ranged from −0.67 to 1.00, M =0.3, SD = 0.25) and positive emotions (men’s scores ranged from −0.87 to 1.00, M = 0.28, SD = 0.45; women’s scores ranged from −1.00 to 1.00, M = 0.34, SD = 0.45) for each of the six 30-second HAMS for each partner. Higher positive scores reflect greater agreement between partners, or greater empathic accuracy by one partner in reading the other partner’s emotions, whereas lower scores (including negative correlations) indicate increasingly less empathic accuracy between partners.

Data Analysis

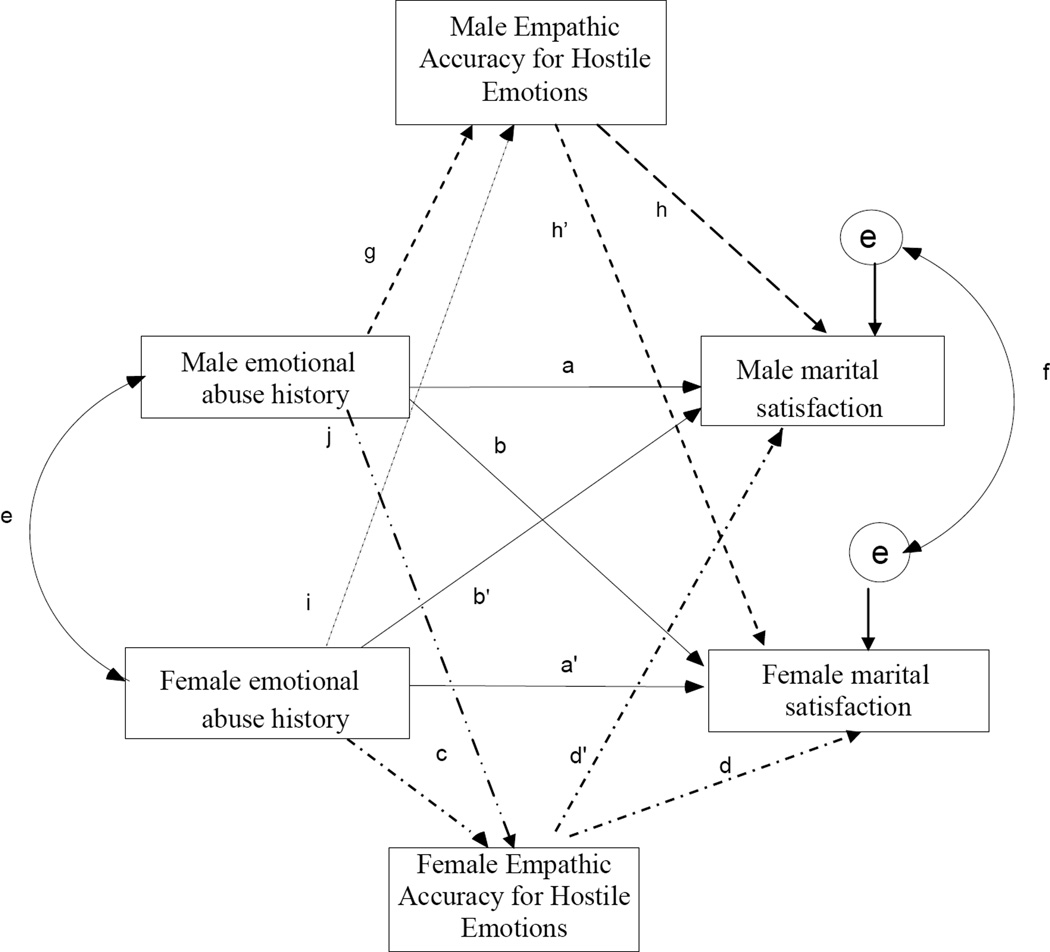

The proposed APIM is illustrated in Figure 1. Actor effects capture the influence of each individual’s childhood emotional abuse on his/her own marital satisfaction (solid paths a and a’ for men and women respectively), and partner effects reflect the influence of each individual’s childhood emotional abuse on his/her partner’s marital satisfaction (solid paths b and b’ for men and women respectively). For actor effects or partner effects to be estimated accurately, they have to be examined while controlling for the other effects; that is, to understand, for example, the influence of wives’ emotional abuse histories on their own satisfaction (an actor effect) the model must simultaneously account for the influence of wives’ emotional abuse histories on their husbands’ marital satisfaction (partner effect) and the influence of husbands’ emotional abuse histories on wives’ marital satisfaction (partner effect). The double-headed arrow between both partners’ histories of abuse (path e) accounts for influences that may be responsible for associations between partners in their report of childhood abuse histories, such as assortative mating processes. The double-headed arrow between both partners’ marital satisfaction (path f) acknowledges the ways in which each partner’s marital satisfaction might influence the other’s satisfaction. Once significant pathways in the relationship between childhood emotional abuse and marital satisfaction were established in the APIM (represented by solid lines in Figure 1), empathic accuracy was then examined as a potential mediating variable (represented by dashed lines in Figure 1). Based on our hypotheses we predicted that empathic accuracy would be influenced by one’s own history of abuse (represented in Figure 1 by paths c and g) as well as a partner’s history of abuse (paths i and j) and would affect marital satisfaction (paths d, d’, h and h’). APIMs were implemented using AMOS SEM software version 17.0 (Locke & Wallace, 1959).

Figure 1.

Actor and partner effects of severity of childhood emotional abuse on marital satisfaction with empathic accuracy as a mediator.

Results

Preliminary correlational analyses of the links between childhood emotional abuse, marital satisfaction and partners’ empathic accuracy for hostile emotions were conducted and revealed significant relationships for both men and women (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Pearson correlations between severity of childhood emotional abuse, marital satisfaction and empathic accuracy for hostile emotions for men and women (N = 156 couples).

In order to clarify the nature of these links APIM analyses were implemented. The basic APIM (illustrated by the solid lines in Figure 1) is a fully saturated model, and therefore no traditional fit indices are available (Cook & Kenny, 2005). The basic model accounts for 13.4% of the total variance in women’s marital satisfaction and 11.6% of the total variance in men’s marital satisfaction. The model indicates the presence of both actor and partner effects for both men and women. The severity of men’s childhood emotional abuse is negatively linked with their own marital satisfaction (β = −0.27, p< 0.01) and negatively linked with their partner’s marital satisfaction (β = −0.20, p <0.01). Likewise, the severity of women’s childhood emotional abuse is negatively linked with their own (β = −0.26, p <0.01) and their partner’s marital satisfaction (β = −0.16, p = 0.04). Men’s and women’s reports of childhood emotional abuse are also positively linked (β = 0.24, p = 0.04).

Empathic accuracy was then added to the APIM as a potential mediator between childhood emotional abuse and marital satisfaction. Separate models were estimated for empathic accuracy of positive and hostile emotions. APIM analyses indicate that only empathic accuracy for hostile emotions (e.g., anger, irritation) is linked with both the severity of childhood emotional abuse and marital satisfaction, whereas empathic accuracy for positive emotions (e.g. happy, close to my partner, etc.) was not linked with severity of emotional abuse for women (β = 0.08 p = 0.35) or for men (β = 0.096 p = 0.25). Results modeling empathic accuracy of hostile emotions as a mediator are presented in Figure 2 and summarized below. The model accounts for 18.5% of the total variance in women’s marital satisfaction and 14.1% of the total variance in men’s marital satisfaction. Women’s empathic accuracy of hostile emotions was significantly linked with their own emotional abuse histories (β = −0.28, p <0.01) and with both their own marital satisfaction (β = 0.16, p = 0.05) and their partner’s marital satisfaction (β = 0.17, p = 0.03). The relationship between women’s emotional abuse and man’s marital satisfaction became non-significant with the addition of empathic accuracy indicating mediation of that relationship. At the same time the addition of empathic accuracy for hostile emotions reduced the magnitude of the direct relationship between women’s emotional abuse and their own marital satisfaction (from β = 0.26 to β = 0.19) but this direct path remained significant suggesting the presence of partial mediation or an indirect effect of women’s empathic accuracy. Women’s empathic accuracy was not significantly linked with their partners’ emotional abuse history. On the other hand, men’s empathic accuracy was negatively significantly linked with both their own emotional abuse history (β = −0.24, p = 0.002) and their partner’s emotional abuse history (β = − 0.20, p = 0.01). Men’s empathic accuracy was not significantly linked to their own marital satisfaction and was only weakly linked to their partners’ satisfaction (β = 0.15, p = 0.06).

Figure 2.

Actor and partner standardized effects of childhood emotional abuse on marital satisfaction mediated by men’s and women’s empathic accuracy of hostile emotions

Note: figure presents standardized coefficients; dashed lines represent paths involved in mediation.

+p< .10; * p< .05; ** p< .01

a = path coefficient without mediation

In order to examine these relationships further, and to take advantage of traditional Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) fit statistics to assess the fit of our model to the data, we constrained non-significant paths to zero (Figure 3). A non-significant Chi-Square (χ2 = 4.73, p = 0.2) and additional fit indices for this APIM indicated that the model fit the data well (CFI = 0.989, RMSEA = 0.06). The Bollen-Stine bootstrap also confirmed that our data fit the model well (p < 0.99). This model accounted for 16% of the total variance in women’s marital satisfaction and also 12% of the total variance in men’s marital satisfaction. In this model, women’s emotional abuse history was significantly linked with both their own empathic accuracy (β = −0.31, p < 0.01) and with their partner’s empathic accuracy (β = −0.21, p = 0.008). Both men’s empathic accuracy and women’s empathic accuracy were also linked with women’s marital satisfaction, and the link between women’s emotional abuse history and their marital satisfaction was mediated (β = −0.13, p = 0.06) by their own (actor effect) and their partner’s (partner effect) empathic accuracy. Men’s empathic accuracy was also significantly linked with their own history of emotional abuse; however the relationship between men’s history of emotional abuse and their partner’s satisfaction remained statistically significant, albeit dropped from β = −0.20 to β = −0.16 indicating again the presence of an indirect effect that is not however a full mediator.

Figure 3.

Actor and partner standardized effects of childhood emotional abuse on marital satisfaction mediated by men’s and women’s empathic accuracy of hostile emotions with nonsignificant paths constrained.

Note: figure presents standardized coefficients; dashed lines represent paths involved in mediation.

+p< .10; * p< .05; ** p< .01

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine links between childhood emotional abuse and marital satisfaction in couples using a model that simultaneously accounts for both intra-individual (actor effects) and interpersonal influences (partner effects). Implementation of APIMs allowed us to examine how individuals’ severity of childhood emotional abuse is associated both with their own marital satisfaction and with their partner’s satisfaction. We also examined partners’ empathic accuracy for each other’s negative emotions as a possible mediator of the link between severity of childhood emotional abuse and relationship satisfaction.

Emotional Abuse and Marital Satisfaction

The results from the APIM analyses indicate that severity of childhood emotional abuse is linked with one’s own marital satisfaction for both men and women (intra-individual or actor effects). This is consistent with prior research (Bradbury & Shaffer, 2012; DiLillo et al., 2009). Our APIM analyses also indicated that, for both men and women, severity of childhood emotional abuse is also linked with their partners’ marital satisfaction (interpersonal or partner effects). Although previous studies of the effects of childhood abuse on relationship satisfaction have also used data from couples (DiLillo et al., 2009), this is the first study to our knowledge to examine actor and partner effects using an APIM approach. Simultaneously examining actor and partner effects ensures that each effect is estimated appropriately rather than subject to confounding by the other. The presence of links between individuals’ histories of emotional abuse and their partners’ satisfaction (partner effect) in relationships over and above the intrapersonal impact (actor effect) of childhood abuse has important clinical implications for couples’ therapy. This finding highlights the importance of considering how the sequelae that result from exposure to childhood emotional abuse might contribute to a partner’s dissatisfaction in the relationship. It therefore becomes important for couples’ therapists to look for childhood experiences of abuse in both partners that can be currently affecting their relationship, and for ways that one partner’s abuse history may establish patterns of interaction that contribute to the dissatisfaction of the other.

Empathic Accuracy

Empirical findings show a link between empathic accuracy and marital satisfaction (Cohen, et al., 2012), but less attention has been paid to developmental factors that may foster empathic inaccuracy and thereby impact relationships. Our results indicate that the severity of childhood emotional abuse is linked with one’s ability to accurately read a partner’s negative emotions; those reporting more child emotional abuse have greater difficulty accurately reading their partner. Past research has demonstrated that exposure to emotional abuse contributes to the development of a negative attribution style (Gibb, 2002). This negative lens is likely to impact the way one perceives not only oneself but also others, which becomes particularly important in the context of a relationship and can lead to misperceiving a partner’s emotions. In our study the relationship between emotional abuse and empathic inaccuracy only held true for negative (hostile) emotions. This is consistent with previous studies, which have shown that individuals are more prone to misperceive emotions in highly charged moments (Waldinger & Schulz, 2006), whereas they may be more likely to read positive emotions such as happiness accurately.

We also predicted that empathic accuracy would be influenced by a history of emotional abuse in one’s partner. Empathic accuracy depends not only on the perceiver but also on the ability of the person experiencing the emotions to express them accurately. This signaling ability can be impaired in individuals with histories of emotional abuse (Zaki et al., 2008). Our results indicate that men’s empathic inaccuracy was influenced not only by their own histories of abuse (actor effect) but also by their partners’ histories of emotional abuse (partner effect). Our data do not provide us with information on the source of this empathic inaccuracy - that is, whether the source of miscommunication is the perceiver or the signaler or both. Difficulties with signaling emotions, however, could be a possible mechanism driving this partner effect and would warrant further investigation in future studies. Our results also indicate that women’s empathic accuracy was only influenced by their own abuse histories and not subject to a partner effect. The reason for this difference is unclear at this point and would warrant further investigation in future studies.

This study also provides support for the role of empathic accuracy in reading negative emotions as a mediator of the link between emotional abuse and marital satisfaction. Women’s accuracy in reading their partners’ negative emotions mediated the link between the severity of their childhood emotional abuse and their partners’ marital satisfaction. Evidence was also found for mediation of intrapersonal effects (actor effects) of abuse on women’s marital satisfaction. These findings shed light onto possible mechanisms by which childhood emotional abuse has long-lasting effects on adult intimate relationships despite the temporal distance between the two. For women who were victims of childhood emotional abuse, less accurate reading of a partner’s negative emotions can make for misunderstandings that affect their happiness in the marriage, and such inaccuracy may contribute to their partners also feeling poorly understood. Study findings also suggest the possible utility of focusing in couples’ treatment on how one’s abuse history shapes the ability to read the other’s emotions and on the partner’s experiences of feeling misread.

Our results also indicate that men’s ability to read their partners’ negative emotions mediated the link between a woman’s emotional abuse and her marital satisfaction; women’s histories of emotional abuse were linked with poorer empathic accuracy by their partners, which in turn was associated with lower marital satisfaction (unsaturated model, Fig. 3). This finding highlights the complexity of intimate relationships and the likely dyadic effects that are constantly at play. Prior studies have already demonstrated the importance for women’s relationship satisfaction of feeling understood by a partner (Cohen et al., 2012), our study however has also shed light on the dyadic interplay between partners’ whose histories of childhood emotional abuse can then influence the other’s ability to accurately read them. Contrary to our hypothesis, the relationship between men’s emotional abuse history and their partners’ relationship satisfaction was not mediated by their own or their partners’ empathic accuracy. The full pattern of findings implies that men’s emotional abuse histories may affect relationships in other ways that are not clearly understood at this time.

Although our results indicate that empathic accuracy partially mediates the relationship between childhood emotional abuse and marital satisfaction, our models accounted for a moderate amount of the variance, and it is important to note that other mechanisms may also be at play that could potentially explain this link. For example, mental health outcomes such as depression may also contribute to the marital difficulties of survivors of childhood emotional abuse. Future research should focus on further clarifying the relationship between emotional abuse and marital dissatisfaction by addressing other possible mechanisms.

Implications, Limitations and Future Directions

If replicated, these findings have important clinical implications for couples’ therapy. Although most clinicians routinely ask about histories of childhood physical and sexual abuse, they may be less attentive to obtaining histories of emotional maltreatment. Findings from this study suggest that specific attention to histories of childhood emotional abuse may be particularly important in understanding the underpinnings of adult relationship distress. With clients who report such histories, therapists may pay special attention to the ability to read partners’ emotions particularly in negatively charged interactions. In addition, treaters might focus on how a history of emotional abuse may affect one’s ability to communicate emotions in ways that can be ―read‖ by partners. Helping partners understand how they express and read each other’s emotions is an important component of many couples’ therapies.

An important strength of the study is that the sample was diverse and community-based. This study also uses a video recall method to examine the emotional experiences and perceptions of individuals as they unfold in real couples’ interactions. This approach captures important ―in vivo‖ emotional reactions among partners and does not depend on questionnaires that ask about typical emotional experiences or perceptions in a couple’s relationship (Waldinger, Hauser, Schulz, Allen, & Crowell, 2004; Waldinger & Schulz, 2006).

This study also has certain limitations that are important to consider. It is a cross-sectional study; findings are correlational and cannot inform us directly about causation. Future study designs that build in temporal separation between assessments of empathic accuracy and marital satisfaction would be helpful in establishing the direction of effects. This study also relied on retrospective self-report data for childhood emotional abuse, and recall bias cannot be ruled out and could have led to either under or over-reporting of histories of abuse. Another limitation of our study is the fact that our sample only included heterosexual couples. Repeating this study with both homosexual and heterosexual couples, as well as a more ethnically diverse sample will provide important information. Finally, our sample size was limited to 156 couples, raising the possibility that the absence of an expected mediation between men’s histories of childhood emotional abuse and theirs and their partner’s relationship satisfaction by their empathic accuracy might have been due to insufficient statistical power to detect this. Nevertheless, this study represents an advance in the examination of links between childhood trauma and relationship satisfaction, as well as links between childhood trauma and empathic accuracy. Our findings illustrate the importance of considering intrapersonal (actor) and interpersonal (partner) influences when examining the link between childhood emotional abuse and marital satisfaction as well as the importance of addressing both partners’ histories of childhood emotional abuse in clinical settings. This dyadic approach can be extended to other forms of childhood abuse, as well as other factors that could contribute to marital dissatisfaction such as low marital trust, personality traits, and attachment style. Future research should also focus on other potential mediators of the link between childhood emotional abuse and marital satisfaction, and investigate whether demographic (SES, education etc.) or relationship-based variables (length of relationship, status of relationship etc.) play a role in this link. Finally, future research should also focus on investigating the effects of treatment on the link between histories of emotional abuse and marital satisfaction.

Acknowledgments

Funded by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (K08 MH01555)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alexander P. Understanding the effects of child sexual abuse history on current couple relationships: An attachment perspective. In: Johnson SM, Whiffen VW, editors. Attachment processes in couple and family therapy. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Fink L, Handelsman L, Foote J, Lovejoy M, Wenzel K, Ruggerio J. Initial reliability and validity of a new retrospective measure of child abuse and neglect. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1994;151:1132–1136. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.8.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury LL, Shaffer A. Emotion dysregulation mediates the link between childhood emotional maltreatment and young adult romantic relationship satisfaction. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma. 2012;21:497–515. [Google Scholar]

- Briere J, Rickards S. Self-awareness, affect regulation, and relatedness: differential sequels of childhood versus adult victimization experiences. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2007;195:497–503. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e31803044e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns EE, Jackson JL, Harding HG. Child maltreatment, emotion regulation, and posttraumatic stress: The impact of emotional abuse. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma. 2010;19:801–819. [Google Scholar]

- Buser TJ, Hackney H. Explanatory style as a mediator between childhood emotional abuse and nonsuicidal self-injury. Journal of Mental Health Counseling. 2012;34:154–169. [Google Scholar]

- Carrére S, Buehlman KT, Gottman JM, Coan JA, Ruckstuhl L. Predicting marital stability and divorce in newlywed couples. Journal of Family Psychology. 2000;14(1):42–58. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.14.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P, Coccaro EF, Lee R, Jacobson KC. Moderating effects of childhood maltreatment on associations between social information processing and adult aggression. Psychological Medicine. 2012;42:1293–1304. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711002212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung GW, Lau RS. Testing mediation and suppression effects of latent variables: Bootstrapping with structural equation models. Organizational Research Methods. 2008;11:296–325. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Schulz MS, Weiss E, Waldinger RJ. Eye of the beholder: the individual and dyadic contributions of empathic accuracy and perceived empathic effort to relationship satisfaction. Journal of Family Psychology. 2012;26:236–245. doi: 10.1037/a0027488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook WL, Kenny DA. The Actor-Partner Interdependence Model: A model of bidirectional effects in developmental studies. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2005;29(2):101–109. [Google Scholar]

- Delucchi KL, Bostrom A. Methods for Analysis of Skewed Data Distributions in Psychiatric Clinical Studies: Working with Many Zero Values. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161(7):1159–1168. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.7.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiLillo D, Long PJ. Perceptions of Couple Functioning Among Female Survivors of Child Sexual Abuse. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse. 1999;7(4) [Google Scholar]

- DiLillo D, Peugh J, Walsh K, Panuzio J, Trask E, Evans S. Child maltreatment history among newlywed couples: A longitudinal study of marital outcomes and mediating pathways. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77(4):680–692. doi: 10.1037/a0015708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Boden JM, Horwood LJ. Exposure to childhood sexual and physical abuse and adjustment in early adulthood. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2008;32(6):607–619. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Browne A. The traumatic impact of child sexual abuse: A conceptualization. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1985;55:325–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1985.tb02703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeston MH, Plechaty M. Reconsideration of the Locke-Wallace Marital Adjustment Test: is it still relevant for the 1990s? Psychological Reports. 1997;81(2):419–434. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1997.81.2.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibb BE. Childhood maltreatment and negative cognitive styles. A quantitative and qualitative review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2002;22(2):223–246. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(01)00088-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibb BE, Abela JRZ. Emotional abuse, verbal victimization, and the development of children’s negative inferential styles and depressive symptoms. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2008;32(2):161–176. [Google Scholar]

- Godbout N, Sabourin Sp, Lussier Y. Child sexual abuse and adult romantic adjustment: Comparison of single- and multiple-indicator measures. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2009;24(4):693–705. doi: 10.1177/0886260508317179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottman JM. What predicts divorce?:The relationship between marital processes and marital outcomes. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Heider F. The Psychology of interpersonal relations. New York, NY: Wiley & Sons, Inc; 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Ickes W, Simpson JA. Empathic accuracy. New York: Guilford Press; 1997. Managing empathic accuracy in close relationships; pp. 218–250. [Google Scholar]

- Ickes W, Simpson JA. Motivational aspects of empathic accuracy. In: Fletcher GJO, Clark M, editors. The Blackwell hand-book of social psychology: Interpersonal processes. Oxford, England: Blackwell Publishers; 2001. pp. 229–249. [Google Scholar]

- Kashy DA, Kenny DA, Reis HT, Judd CM. Handbook of research methods in social and personality psychology. New York, NY US: Cambridge University Press; 2000. The analysis of data from dyads and groups; pp. 451–477. [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick SD, Bissonnette VL, Rusbult CE. Empathic accuracy and accommodative behavior among newly married couples. Personal Relationships. 2002;9(4):369–393. [Google Scholar]

- Locke HJ, Wallace KM. Short Marital-Adjustment and Prediction Tests: Their Reliability and Vaildity. Marriage and Family Living. 1959;21(3):251–255. [Google Scholar]

- Locke HJ, Wallace KM. Locke-Wallace marital adjustment test. In: Corcoran K, Fischer J, editors. Measures of clinical practice. London, UK: Macmillan; 1987. pp. 451–453. [Google Scholar]

- Maneta E, Cohen S, Schulz M, Waldinger RJ. Links between childhood physical abuse and intimate partner aggression: the mediating role of anger expression. Violence & Victims. 2012;27(3):315–328. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.27.3.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messman-Moore TL, Coates AA. The impact of childhood psychological abuse on adult interpersonal conflict: The role of early maladaptive schemas and patterns of interpersonal behavior. Journal of Emotional Abuse. 2007;7(2):75–92. [Google Scholar]

- Perry AR, DiLillo D, Peugh J. Childhood psychological maltreatment and quality of marriage: The mediating role of psychological distress. Journal of Emotional Abuse. 2007;7(2):117–142. [Google Scholar]

- Polusny MA, Follette VM. Long-term correlates of child sexual abuse: Theory and review of the empirical literature. Applied & Preventive Psychology. 1995;4(3):143–166. [Google Scholar]

- Rose DT, Abramson LY. Developmental predictors of depressive cognitive style: Research and Theory. In: Cicchetti D, Toth SL, editors. Developmental Perspectives on depression. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press; 1992. pp. 323–349. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz M, Waldinger RJ. Looking in the mirror: Participant observation of affect using video recall in couple interactions. In: Kerig P, Baucom D, editors. Couple observational coding systems. Hillsdale NJ: Erlbaum; 2004. pp. 257–270. [Google Scholar]

- Schweinle WE, Ickes W, Bernstein IH. Empathic inaccuracy in husband to wife aggression: The overattribution bias. Personal Relationships. 2002;9(2):141–158. [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods. 2002;7(4):422–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sillars A, Smith T, Koerner A. Misattributions contributing to empathic (in)accuracy during parent-adolescent conflict discussions. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2010;27(6):727–747. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson JA, Oriña MM, Ickes W. When Accuracy Hurts, and When It Helps: A Test of the Empathic Accuracy Model in Marital Interactions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;85(5):881–893. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.5.881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, A. f. C. a. F. Child Maltreatment 2012. 2013 Retrieved from http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/cb/research-data-technology/statistics-research/child-maltreatment.

- Waldinger RJ, Hauser ST, Schulz MS, Allen JP, Crowell JA. Reading others emotions: The role of intuitive judgments in predicting marital satisfaction, quality, and stability. Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18(1):58–71. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.1.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldinger RJ, Schulz MS. Linking hearts and minds in couple interactions: intentions, attributions, and overriding sentiments. Journal of Family Psychology. 2006;20(3):494–504. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.3.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldinger RJ, Toth SL, Gerber A. Maltreatment and internal representations of relationships: Core relationship themes in the narratives of abused and neglected preschoolers. Social Development. 2001;10(1):41–58. [Google Scholar]

- Whisman MA, Uebelacker LA, Weinstock LM. Psychopathology and Marital Satisfaction: The Importance of Evaluating Both Partners. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72(5):830–838. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.5.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright MO. The long-term impact of emotional abuse in childhood: Identifying mediating and moderating processes. Journal of Emotional Abuse. 2007;7(2):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Wright MO, Crawford E, Del Castillo D. Childhood emotional maltreatment and later psychological distress among college students: the mediating role of maladaptive schemas. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2009;33(1):59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaki J, Bolger N, Ochsner K. It Takes Two: The Interpersonal Nature of Empathic Accuracy. [Article] Psychological Science. 2008;19(4):399–404. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]