Abstract

Ribosomal proteins S4 and S5 participate in the decoding and assembly processes on the ribosome and the interaction with specific antibiotic inhibitors of translation. Many of the characterized mutations affecting these proteins decrease the accuracy of translation, leading to a ribosomal-ambiguity phenotype. Structural analyses of ribosomal complexes indicate that the tRNA selection pathway involves a transition between the closed and open conformations of the 30S ribosomal subunit and requires disruption of the interface between the S4 and S5 proteins. In agreement with this observation, several of the mutations that promote miscoding alter residues located at the S4-S5 interface. Here, the Escherichia coli rpsD and rpsE genes encoding the S4 and S5 proteins were targeted for mutagenesis and screened for accuracy-altering mutations. While a majority of the 38 mutant proteins recovered decrease the accuracy of translation, error-restrictive mutations were also recovered; only a minority of the mutant proteins affected rRNA processing, ribosome assembly, or interactions with antibiotics. Several of the mutations affect residues at the S4-S5 interface. These include five nonsense mutations that generate C-terminal truncations of S4. These truncations are predicted to destabilize the S4-S5 interface and, consistent with the domain closure model, all have ribosomal-ambiguity phenotypes. A substantial number of the mutations alter distant locations and conceivably affect tRNA selection through indirect effects on the S4-S5 interface or by altering interactions with adjacent ribosomal proteins and 16S rRNA.

INTRODUCTION

Cellular protein synthesis systems translate mRNAs quickly and with high accuracy. The accuracy of the decoding process can, however, be altered by agents such as the antibiotic streptomycin that promote miscoding and by mutations in rRNA, ribosomal proteins, or translation factors (1). Among the first such accuracy mutants to be characterized were some of the streptomycin-resistant Escherichia coli strains carrying alterations in ribosomal protein S12 (2). Subsequently, E. coli mutants carrying altered ribosomal protein S4 or S5 were isolated that supported increased levels of miscoding (3–5). Since those early studies, many other mutants have been isolated that affect the accuracy of decoding and carry alterations in different components of the translation machinery (1, 4).

The determination of high-resolution structures of ribosomes has offered structural interpretations of the effects of some accuracy-altering ribosomal mutations (6). X-ray crystallography of ribosomal complexes has shown that conserved RNA elements of the decoding center use a shape-sensing mechanism to monitor base pairing between the A site codon and the anticodon of incoming aminoacyl-tRNA. Successful interaction of a ternary complex of EF-Tu–GTP–aminoacyl-tRNA with mRNA in the decoding center triggers a series of conformational rearrangements of the head and shoulder domains of the 30S subunit, ultimately resulting in the formation of a “closed” 30S subunit conformation (7). Comparison of vacant and tRNA-bound 30S subunits showed that transition to the closed conformation involved the formation of new S12-rRNA interactions and the disruption of some S4-S5 contacts. For instance, in the closed conformation, R53 and K42 of S12 contact h44 and h27, respectively, and mutations in these S12 residues, which are predicted to inhibit domain closure, have error-restrictive phenotypes. Similarly, transition to the closed conformation requires disruption of contacts along the interface between proteins S4 and S5 and many of the previously described error-promoting, ribosomal-ambiguity (ram) mutations in these proteins map to interface residues. Thus, disruption of the S4-S5 contacts at their interface by mutation is predicted to facilitate the transition to a closed 30S subunit conformation, neatly explaining the phenotypes and locations of the classic S4 and S5 accuracy-altering mutations (7).

Despite its appealing ability to integrate structural, genetic, and biochemical data, some observations do not support the notion that accuracy-altering mutations must necessarily affect the S4-S5 interface. In the early genetic studies, it was found that combinations of error-restrictive S12 mutations and error-prone ram S4 (or S5) proteins generated a quasi-wild-type error phenotype (3, 5). In terms of the open/closed model, these combinations could be explained by a simple compensation mechanism. However, Björkman et al. (8) reported on some novel mutations in S4 that were error restrictive but that nonetheless also reversed the restrictiveness of classic S12 mutations, seemingly in conflict with the predictions of the open/closed model. Work by the Culver lab showed that a G27D substitution in S5 (E. coli numbering is used throughout and omits the N-terminal Met) in a region remote from the interface with S4 increased miscoding through effects on rRNA processing and subunit assembly (9). This offers an alternative explanation for the effects on decoding for at least some mutant proteins. The S4-S5 interaction and the effects of accuracy-altering interface mutations have been tested in the context of a yeast two-hybrid system (10). In this albeit artificial context, proteins S4 and S5 did interact with one another and some accuracy-altering mutations affected their interactions. However, the effects of the mutations on S4-S5 interactions did not reflect their ribosomal error phenotypes or predicted effects on S4-S5 interface destabilization. More recently, two 16S rRNA mutations that promote miscoding, G299A and G347U, have been analyzed by X-ray crystallography of the mutant 70S ribosomes (11). Both mutations were found to disrupt bridge B8, one of the intersubunit bridges connecting 30S and 50S subunits in the 70S ribosome. This was not unexpected in the G347U mutant, since this region of the 16S rRNA forms part of bridge B8. However, G299 is some 80 Å away from bridge B8. Moreover, G299 is close to the S4-S5 interface, raising the possibility that the effects of alterations in proteins S4 and S5 on decoding are also propagated through bridge B8 (11, 12). The position of bridge B8 relative to S4 and S5 is shown in Fig. S1 in the supplemental material.

In an effort to gain a better understanding of the range of S4 and S5 residues involved in the modulation of decoding fidelity, we targeted the rpsD and rpsE genes encoding these proteins for mutagenesis. In previous genetic studies, S4 and S5 mutants were typically isolated on the basis of their ability to reverse the decreased growth, dependence on streptomycin, or error-restrictive effects of S12 alterations (3, 5). In addition, some S5 mutants were also recovered in selections for resistance to spectinomycin or neamine (13, 14). With some exceptions, these selections mostly succeeded in isolating a limited number of error-prone S4 and S5 mutants. We have previously shown that when recombineering approaches are applied to the rpsL gene encoding S12, novel mutant proteins with diverse effects on decoding can be recovered (15). Here, recombineering allowed us to recover a wide array of alterations in S4 and S5 with diverse effects on decoding fidelity. Many of the substitutions are in residues distant from the S4-S5 interface, and few have pronounced effects on rRNA processing or ribosome assembly.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

E. coli MC323 (F− λ− lacZ521 [Tn10 linked] rph-1) was the host strain used for recombineering and screening for accuracy-altering mutations. MC361 [F− ara Δ(gpt-lac)5 thi prfB (from E. coli B)] carries the fully active A246 RF2 allele (16) and was used for reconstruction of the selected mutants. Plasmids pKD46, pKD4, and pCP20 were used in recombineering (17).

The lacZ plasmid pLG3/4 UGA, carrying a UGA stop codon in the 5′ region of the coding sequence, was used to monitor stop codon readthrough (18). The ampicillin resistance-encoding dual-luciferase plasmids pEK4, pEK5, pEK7, and pEK24 were a gift from Philip Farabaugh, University of Maryland, and were used to monitor missense decoding. These plasmids encode a single polypeptide consisting of the firefly luciferase (F-luc) fused in frame to the Renilla luciferase (R-luc). Lysine 529 of F-luc is an essential active-site residue, and plasmid pEK4 carries the wild-type lysine 529 codon. In plasmids pEK7 and pEK24, the AAA lysine codon at position 529 has been replaced with AAU (Asn) and AGG (Arg), respectively. In strains carrying pEK7 or pEK24, near-cognate decoding of AGG or AAU by the AAA/G-decoding tRNALys is required for the synthesis of proteins with F-luc activity. Plasmid pEK5 carries a UUU codon at position 529 and served as a negative control.

Random mutagenesis of rpsD and rpsE.

The rpsD gene encoding the S4 protein and the rpsE gene encoding the S5 protein were each targeted for random mutagenesis. To facilitate subsequent genetic manipulations, a kanamycin resistance cassette was first linked to each of the genes by recombineering techniques. The intergenic spacers between rpsD and rpoA and between rpsE and rpmD are 24 and 3 nucleotides, respectively, so the kanamycin resistance cassette was inserted immediately after the stop codon in both the rpsD and rpsE genes. MC323 carries a premature UGA mutation in the lacZ gene (lacZ521). Because of near-cognate decoding of UGA by tRNATrp, this lacZ allele supports a low level of β-galactosidase activity and MC323 colonies appear pale blue on 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-Gal) plates, facilitating the detection of increased and decreased UGA readthrough by error-prone and error-restrictive ribosomes, respectively.

For random mutagenesis, a 1.2-kb segment of DNA encoding S4 or S5 linked to the kanamycin resistance cassette was amplified with the error-prone polymerase Mutazyme (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) as recommended by the manufacturer. The template concentrations and amplification conditions were adjusted to allow the incorporation of one or two errors per amplified molecule. Electrocompetent MC323 cells expressing λ Red recombinase were electroporated with this randomly mutagenized DNA and plated on LB medium containing kanamycin, isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG), and X-Gal. Kanamycin-resistant colonies that were either bluer or whiter than the wild type were identified, purified, and sequenced. Selected rpsD or rpsE alleles that showed altered lac phenotypes on X-Gal plates were transferred into MC361 by P1-mediated transduction. The kanamycin resistance cassettes were removed by transient expression of the Flp recombinase, and the rpsD or rpsE gene from each kanamycin-sensitive strain was resequenced to confirm the presence of the desired mutation and the absence of any additional, unanticipated base changes.

Growth rate and antibiotic sensitivity determinations, enzyme assays, and rRNA processing and ribosome analyses.

Growth rate determination was carried out in LB medium at 37°C. Temperature sensitivity was analyzed by plating 10-fold serial dilutions of overnight cultures on LB agar plates and incubating them at 20°C, 37°C, or 42°C for 24 to 48 h. Antibiotic resistances were determined by 2-fold serial dilution of each antibiotic (streptomycin for S4 and S5; spectinomycin for S5) in 96-well microtiter dishes.

Detergent lysates of logarithmically growing cells were prepared as described previously. 30S and 50S subunits were separated from 70S ribosomes and polysomes by centrifugation through linear 10 to 40% sucrose gradients in a Beckman SW28 rotor for 18 h at 38,191 × g. The gradients were analyzed on an ISCO gradient fractionator connected to an ISCO UV5 detector.

Isolation of total RNA from logarithmically growing cells and analysis of rRNAs on 0.7% agarose–0.9% Synergel was carried out as described by Wachi et al. (19). In addition, RNAs were also isolated from wild-type strains treated with chloramphenicol (final concentration of 60 mg/liter) for 30 min. Chloramphenicol is known to inhibit rRNA processing and leads to the accumulation of 17S precursors of 16S rRNA (20, 21).

Firefly (F-luc) and Renilla (R-luc) luciferase activities were assayed with the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega, Madison, WI). Cell lysates were prepared and assayed by following the manufacturer's instructions, and luminescence was measured with a GloMax 20/20 luminometer. R-luc activity served as an internal standard to control for variations in mRNA and protein levels between cultures. Each plasmid-containing strain was assayed at least in triplicate, and F-luc/R-luc ratios were calculated. The frequency of misreading in strains expressing the K529N or K529R firefly luciferase was expressed (in arbitrary relative light units [RLU]) as the F-luc/R-luc ratio normalized to the F-luc/R-luc ratio from isogenic strains expressing the wild-type K529 firefly luciferase (22). β-Galactosidase assays were performed as described previously and expressed in Miller units (23).

RESULTS

Random mutagenesis of the rpsD and rpsE genes encoding ribosomal proteins S4 and S5.

The rpsD and rpsE genes and their respective linked kanamycin resistance cassettes were each amplified in an error-prone PCR, and the mutagenized fragments were electroporated into strain MC323. The leaky lacZ521 UGA mutation in MC323 was used to identify mutants with increased or decreased decoding fidelity (15). From 20 electroporations with mutated rpsD fragments, 1,221 transformants were recovered on X-Gal, IPTG, and kanamycin plates. Of these, 38 displayed a dark blue, ribosomal-ambiguity phenotype while 3 had an error-restrictive phenotype. Several of the putative ram mutants were unstable and were not pursued. Previous work with Salmonella has shown that certain error-restrictive S4 mutants confer resistance to low levels of streptomycin (8). However, replica printing of all of the transformants onto LB plates supplemented with 10 mg/liter of streptomycin did not yield any streptomycin-resistant colonies. Sequencing of 26 ram mutants showed that 17 carried unique mutations while the 3 restrictive mutants each contained different rpsD sequences (Table 1). Similarly, 21 electroporations with mutated rpsE fragments generated 2,270 transformants that yielded 24 ram and 7 restrictive mutants. Sequencing of 15 of the ram mutants showed that 14 carried unique changes, while 5 unique alterations were found among the 6 sequenced restrictive rpsE mutants (Table 1). A majority of the mutants produced S4 or S5 protein with single amino acid substitutions. However, of the three restrictive S4 mutants, two carried single amino acid substitutions (G86C and L202F) while the remaining mutant carried the G86C substitution along with a Q151P alteration (Table 1). Only the mutant carrying the G86C single amino acid substitution was pursued further. Among the collection of S5 mutants, five (two ram, three restrictive) carried more than one substitution at nonadjacent codons in rpsE. Attempts to separate the mutations and correlate accuracy phenotypes with single amino acid substitutions were unsuccessful, and these S5 double mutants were not studied further. S4 is a primary binding protein, and a surprising feature of the collection of S4 ram mutants is the occurrence (5/20) of truncated S4 proteins. This is nonetheless consistent with previous work that has shown that accuracy-altering rpsD mutations can generate shortened S4 proteins (24). A single mutant had an S4 protein with a two-amino-acid (Tyr-Val) C-terminal extension.

TABLE 1.

Effects of altered S4 and S5 ribosomal proteins on growth and antibiotic sensitivity

| Protein and mutated residue(s)a | Accuracy phenotypeb | Avg DTc (min) ± SD | MIC (μg/ml) of: |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Streptomycin | Spectinomycin | |||

| S4 | ||||

| None | WTd | 28 ± 1 | 12.5 | |

| D49Y | Ribosomal ambiguity | 33 ± 2 | 12.5 | |

| Q53H | Ribosomal ambiguity | 40 ± 2 | 6.25 | |

| Q53P | Ribosomal ambiguity | 37 ± 2 | 12.5 | |

| E68D | Ribosomal ambiguity | 29 ± 1 | 12.5 | |

| R69P | Ribosomal ambiguity | 37 ± 2 | 12.5 | |

| G86C | Restrictive | 30 ± 2 | 25 | |

| G86C, Q151P | Restrictive | NDe | ND | |

| E165* | Ribosomal ambiguity | 50 ± 2 | 12.5 | |

| W169* | Ribosomal ambiguity | 30 ± 1 | 12.5 | |

| E196D | Ribosomal ambiguity | 30 ± 1 | 12.5 | |

| E196* | Ribosomal ambiguity | 32 ± 2 | 12.5 | |

| I199N | Ribosomal ambiguity | 30 + 2 | 6.25 | |

| E201G | Ribosomal ambiguity | 33 ± 1 | 12.5 | |

| E201* | Ribosomal ambiguity | 30 ± 2 | 12.5 | |

| L202F | Restrictive | 33 ± 1 | 12.5 | |

| S204T | Ribosomal ambiguity | 30 ± 2 | 12.5 | |

| K205* | Ribosomal ambiguity | 31 ± 1 | 12.5 | |

| K205E | Ribosomal ambiguity | 31 ± 2 | 12.5 | |

| K205T | Ribosomal ambiguity | 31 ± 1 | 12.5 | |

| +Tyr-Val | Ribosomal ambiguity | 32 ± 2 | 6.25 | |

| S5 | ||||

| None | WT | 28 ± 2 | 12.5 | 50 |

| K13M, S91Y | Ribosomal ambiguity | ND | ND | ND |

| F30V | Restrictive | 31 ± 1 | 25 | 25 |

| E54D, I104T, I140I | Ribosomal ambiguity | ND | ND | ND |

| L75R | Ribosomal ambiguity | 30 ± 2 | 6.25 | 25 |

| L80Q | Ribosomal ambiguity | 56 ± 1 | 25 | 50 |

| G86C | Ribosomal ambiguity | 31 ± 1 | 12.5 | 50 |

| T89S, G86C | Ribosomal ambiguity | ND | ND | ND |

| Q96E | Ribosomal ambiguity | 30 ± 2 | 12.5 | 25 |

| T102I | Ribosomal ambiguity | 27 ± 2 | 12.5 | 25 |

| I104L | Restrictive | 29 ± 1 | 12.5 | 25 |

| A109V | Ribosomal ambiguity | 31 ± 1 | 12.5 | 25 |

| E115Q | Restrictive | 29 ± 2 | 12.5 | 50 |

| N121H | Ribosomal ambiguity | 30 ± 1 | 25 | 25 |

| L123Q | Ribosomal ambiguity | 34 ± 1 | 12.5 | 25 |

| A126D | Ribosomal ambiguity | 31 ± 2 | 12.5 | 25 |

| N134Y | Ribosomal ambiguity | 56 ± 2 | 3.125 | 25 |

| V135L, E162D | Restrictive | ND | ND | ND |

| P149Q | Ribosomal ambiguity | 30 ± 1 | 12.5 | 50 |

Mutations that generate in-frame stop codons are indicated with an asterisk, and +Tyr-Val indicates a C-terminal extension of the protein.

Accuracy phenotypes reflect alterations in readthrough of the lacZ521 (UGA) allele in MC323, used in the initial screening of mutants. Strains carrying multiple changes were not pursued beyond the initial screening and sequencing. The S5 mutant carrying E54D and I104T substitutions also carries a silent I140I alteration. All strains carry, in addition to the changes indicated, an 85-bp “scar” sequence produced by flippase-mediated recombination of the kanamycin resistant cassettes downstream of the S4 or S5 coding region.

DT, doubling time.

WT, wild type.

ND, not determined.

A mutant S4 protein truncated at residue E201 has also been described in Salmonella (8). However, in contrast to the analogous E. coli mutant described here, which has a strong ribosomal-ambiguity phenotype (based on readthrough of the lacZ [UGA] allele in MC323), the Salmonella mutant restricts UGA readthrough and has a decreased rate of polypeptide synthesis and substantially increased resistance to streptomycin (8). To explore this unexpected discrepancy between these two closely related bacteria, the E. coli rpsD fragment carrying the E201* alteration and the downstream kanamycin resistance cassette was amplified and electroporated into MC323 cells expressing λ Red recombinase. Transformants were plated on X-Gal and kanamycin plates. A total of 281 transformants were recovered from nine independent electroporations, and these colonies had either a dark blue (ribosomal-ambiguity) phenotype (191 colonies) or the pale blue color characteristic of cells with wild-type ribosomes (90 colonies). Importantly, no white colonies with an error-restrictive phenotype were recovered. Reconstruction of the E201* mutant in MC361 by transduction also yielded a ram strain (see below). This suggests that either the S4 protein truncated at E201 has divergent effects on decoding in Salmonella enterica and E. coli or additional suppressor mutations are present in the S. enterica strain that alter its decoding properties.

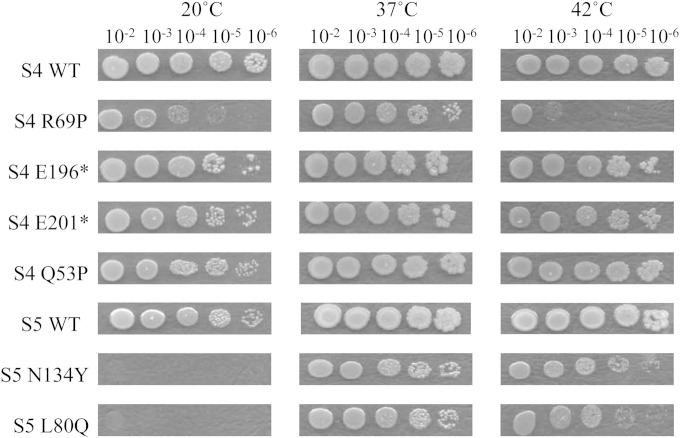

Most of the collection of 19 S4 and 14 S5 mutants characterized here grew well in liquid medium at 37°C (Table 1). Only the S5 mutants carrying L80Q, L123Q, and N134Y substitutions and the S4 mutants carrying Q53H, Q53P, and R69P alterations or truncated at E165 had substantially longer doubling times (>1.2× that of the wild type; Table 1). Similarly, most of the mutants grew well on solid medium at 20°C, 37°C, and 42°C (Fig. 1). Cold sensitivity is a classic phenotype of ribosome assembly-defective mutants. Among the collection, the N134Y and L80Q S5 mutants failed to grow at 20°C while several S4 and S5 mutants, including those with the R69P and Q53P alterations in S4, showed decreased growth at that temperature (Fig. 1). Growth at 42°C was decreased in the R69P S4 mutant and, to a lesser extent, in the N134Y and L80Q S5 mutants (Fig. 1). Nonetheless, the ribosomes in a majority of the mutants assemble and function at levels that can support robust bacterial growth.

FIG 1.

Effects of selected mutations in ribosomal proteins S5 and S4 on growth on solid medium at 20°C, 37°C, and 42°C. Three-microliter aliquots of serially diluted (10−2 to 10−6) overnight cultures of the mutants indicated were spotted onto antibiotic-free LB plates and incubated for 24 to 48 h. WT, wild type.

Several of the previously characterized S4 and S5 mutants display altered sensitivity to the error-inducing antibiotic streptomycin (3, 25). The responses of the mutants isolated here to streptomycin were quantitated in a MIC assay. While eight mutants show 2-fold differences from the wild-type MIC, only the N134Y S5 mutant shows a substantial, 4-fold MIC decrease. Resistance to the aminocyclitol antibiotic spectinomycin can be achieved by alterations in ribosomal protein S5 (26). However, while 10 out of the 14 S5 mutants studied here showed a 2-fold decrease in their spectinomycin MICs, relative to the wild type, none showed an increased MIC (Table 1).

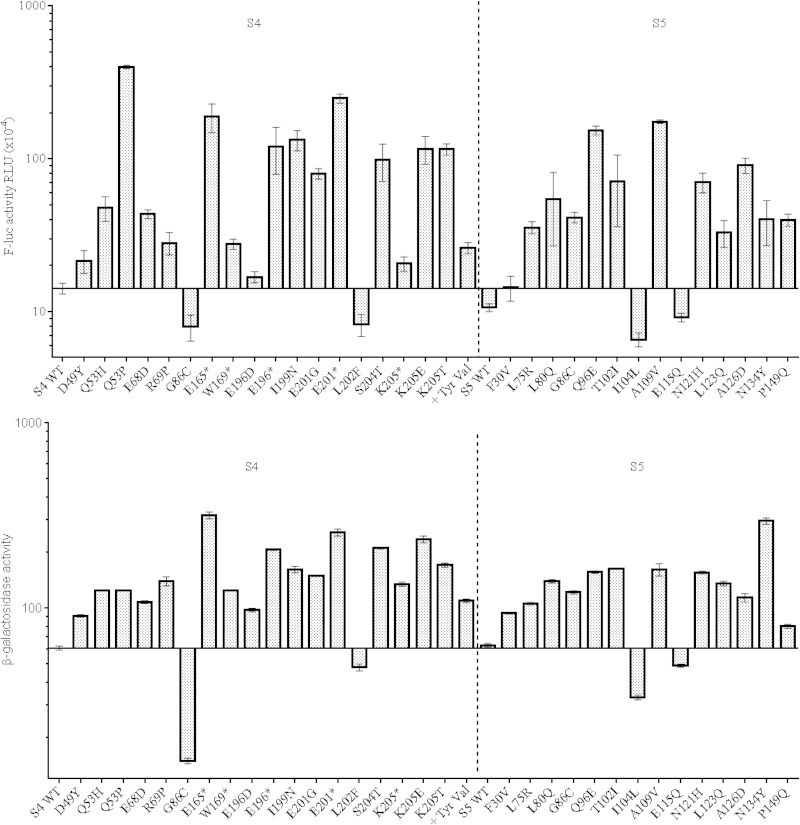

Miscoding properties of S4 and S5 mutants.

Many of the reporter genes used to measure the fidelity of decoding, including the one used here to screen for accuracy-altering mutations, rely on the decoding of a stop codon by a wild-type tRNA. In principle, such readthrough events can reflect defects in either the decoding or the termination process. In contrast, missense errors uniquely reflect the decoding of a sense codon by a near-cognate tRNA. Here, both luciferase-based miscoding and β-galactosidase-based UGA readthrough assays were used to characterize the S4 and S5 mutants, and the results of these assays are presented in Fig. 2. The missense decoding values in Fig. 2 reflect near-cognate decoding of AAU by the AAA/G-decoding tRNALys. Similar patterns of miscoding were obtained with pEK24-transformed cells, encoding a K529R luciferase and requiring near-cognate decoding of AGG by tRNALys (data not shown). By and large, both data sets are consistent with one another; mutants that promote miscoding also promote readthrough. Conversely, the four restrictive mutants analyzed here (G86C and L202F in S4, I104L and E115Q in S5) show reduced UGA readthrough in lacZ (25 to 79% of the assay values of the corresponding wild-type strains), as well as decreased miscoding in the F-luc (K529N) construct used (36 to 64% of the activities measured in the corresponding wild-type strains). All of the ram mutants stimulated both miscoding and readthrough. However, the extents of these effects differed. Relative to wild-type strains, increases in miscoding ranged from 1.4- to 34.3-fold, while readthrough levels ranged from 1.3- to 5.2-fold. Clearly, mutations such as S4 Q53P and S5 A109V stimulate miscoding to a far greater extent (34.3- and 16.3-fold, respectively) than they increase readthrough (3.0- and 4.0-fold, respectively). Other mutations such as S5 L123Q and S4 R69P promote similar levels of miscoding (2.2- and 3.0-fold, respectively) and readthrough (1.5- and 2.3-fold, respectively). The altered decoding properties of the mutants also reflect the screen for readthrough of UGA codons used to isolate them. Had we screened initially for mutants showing altered miscoding (with a missense decoding assay, for instance [27]), it is highly likely that a different spectrum of mutants with a distinct bias for miscoding versus readthrough would have been recovered. Nonetheless, for the S4 and S5 mutants isolated here, while the magnitude of effects on miscoding and readthrough differs among individuals, all of the ribosomal mutations affect both processes.

FIG 2.

Effects of altered ribosomal proteins S4 and S5 on missense decoding (top) and UGA readthrough (bottom). Missense decoding values were obtained from pEK7-transformed cells and reflect near-cognate decoding of AAU by the AAA/G-decoding tRNALys. Misreading levels are expressed in RLU as described in the text. Readthrough levels were obtained from strains transformed with lacZ plasmid pSG3/4 UGA, carrying a UGA mutation in the 5′ end of the β-galactosidase coding region. Bars represent (Miller) units of β-galactosidase activity (43). +Tyr-Val indicates a C-terminal extension of S4. WT, wild type.

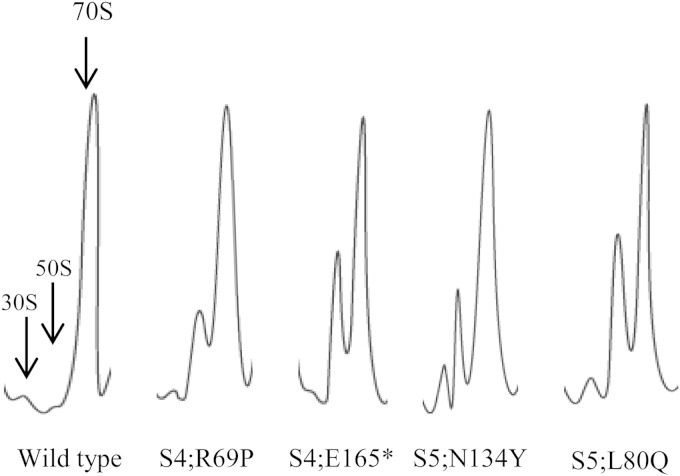

A minority of altered S4 and S5 proteins affect rRNA processing and 30S subunit assembly.

Ribosomal protein S4 is a primary binding protein, and alterations in this protein, including those that alter decoding, have been shown to affect ribosome assembly (28, 29). In addition, recent analysis of ribosomes carrying a G27D alteration in ribosomal protein S5 established a link between defective rRNA processing and translational fidelity (9). These studies raise the possibility that at least some of the phenotypes of ribosomal mutants, including altered decoding, are due to indirect effects on rRNA processing and ribosomal subunit assembly. To pursue this possibility, cell lysates from each of the 33 mutants studied here were analyzed by sucrose gradient centrifugation. Only four mutants (with R69P and E165* in S4 and L80Q and N134Y in S5) displayed ribosome profiles that differed from that; of the wild-type strain (Fig. 3). All four had high levels of 70S ribosomes, and while no additional peaks corresponding to assembly intermediates were observed, gradients of these four mutants contained reduced amounts of free 30S particles and increased amounts of 50S particles, relative to gradients of wild-type ribosomes. This suggests that these specific alterations in S4 and S5 affect the assembly and/or stability of the mutant 30S subunits.

FIG 3.

Ribosome profiles of a wild-type strain and selected S4 and S5 mutants that displayed altered profiles. The positions of 30S and 50S subunits and 70S ribosomes are indicated on the profile of the wild-type strain, and the direction of sedimentation is from left to right.

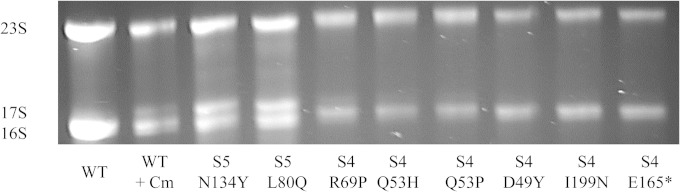

Lysates from each of the 33 ribosomal mutants were also analyzed with the agarose-Synergel system. This gel system can resolve 16S rRNA precursors from mature, processed 16S and 23S rRNAs (19). Of the entire mutant collection, only the S5 L80Q and N134Y mutants showed substantial accumulation of precursor 16S rRNA (Fig. 4). These precursors migrate at the same position as the 17S precursor species produced by the addition of chloramphenicol to wild-type cells (Fig. 4, second lane from the left; [20, 21]), suggesting that a processing step(s) after cleavage of the initial rRNA transcript by RNase III is affected in the mutants (19, 30). These same S5 mutants displayed irregular ribosome profiles and failed to grow at 20°C (Fig. 1 and 3). Of the two S4 mutants with altered ribosome profiles (Fig. 3), only the R69P mutant showed a slight accumulation of precursor 16S rRNA. In repeated rRNA analyses, the S4 E165* mutant, which also displayed an irregular ribosome profile, failed to show any such accumulation of precursor 16S rRNA. The difference in rRNA processing between the S4 and S5 mutants with altered ribosome profiles is noteworthy; while all four mutants have an altered ratio of free 30S to 50S subunits, the 30S peaks are distinctly larger in the two S5 mutants (Fig. 3). This may suggest that while rRNA processing is altered in all four mutants with irregular ribosome profiles, assembling 30S subunits assembled with unprocessed 16S rRNAs are especially unstable in the two S4 mutants. Two additional S4 mutants carrying a Q53H or Q53P substitution showed slight, variable accumulation of precursor 16S rRNA (Fig. 4). Overall, these analyses show that only a minority of the accuracy-altering mutations in proteins S4 and S5 affect rRNA processing and ribosomal subunit assembly.

FIG 4.

rRNA processing in wild-type (WT) and selected S4 and S5 mutant strains. Total RNAs from logarithmically growing wild-type and mutant strains were extracted, electrophoresed on agarose-synergel gels, and stained with ethidium bromide. The second lane from the left contains RNAs extracted from wild-type cells treated with chloramphenicol for 30 min, leading to the accumulation of unprocessed 17S rRNA precursors (20, 21).

DISCUSSION

The accuracy screen used here has succeeded in isolating a large collection of S4 and S5 mutants with effects on decoding. This collection includes many of the accuracy-altering mutations isolated previously in E. coli, Bacillus subtilis, and S. enterica (summarized in Table S1 in the supplemental material). The well-studied E. coli rpsD12, rpsD14, and rpsD16 mutations (22, 24, 31, 32) all generate truncated forms of ribosomal protein S4, and rpsD16 is identical to the W169* mutant isolated here. In S. enterica, selections for compensatory mutations that reversed the streptomycin dependence or slow-growth phenotypes conferred by altered S12 proteins allowed the isolation of S4 proteins with changes at residues D49, Y50, Q53, A78, N84, T85, I199, V200, E201, Y203, S204, and K205 (8, 33). The same selections in B. subtilis led to the isolation of S4 proteins carrying substitutions at E54, as well as insertions or deletions at residues 74 to 78 (34, 35). Early work with E. coli led to the isolation of S5 ram mutants carrying alterations at G103 or R111 (36). Identical mutations affecting decoding were later isolated in B. subtilis (35). The selections in S. enterica for S12-compensating mutations described above also generated S5 mutants carrying alterations at residues A98, G101, I105, A106, G108, R111, I122, and T130. While the majority of the S. enterica mutants were not separated from the S12 mutations(s) and assayed for their specific effects on decoding, the remarkable correspondence between the set of E. coli mutants described here and the S. enterica mutants, isolated through differing selections suggests that a limited set of conserved residues in S4 and S5 are involved in the modulation of decoding activities.

Structural basis for mutant phenotypes.

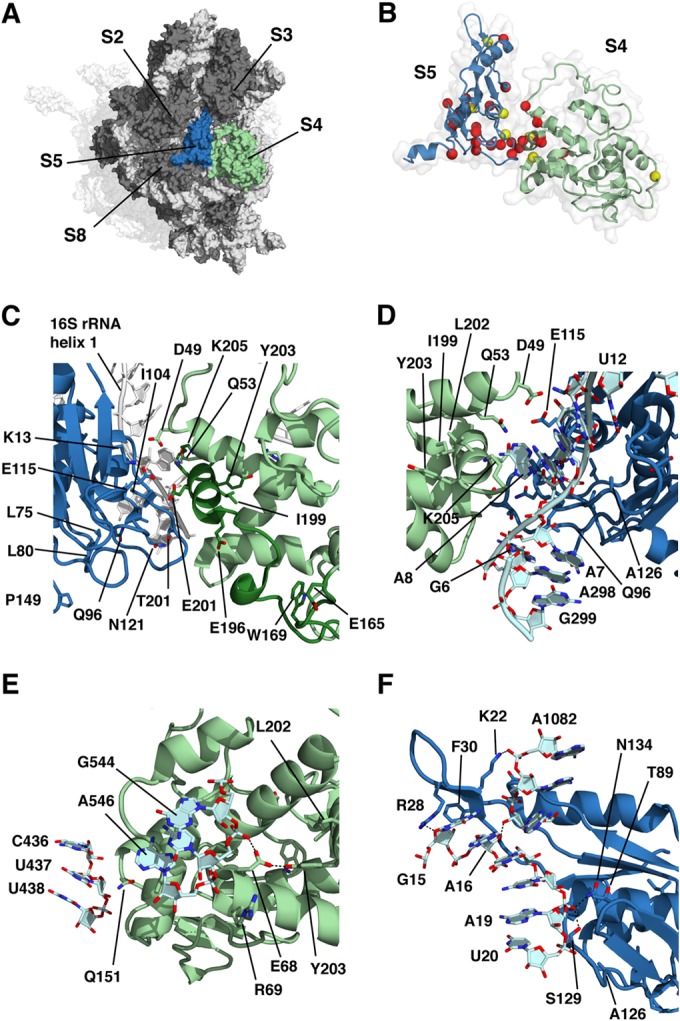

To assess the structural basis for the phenotypes caused by the mutations described above, we examined the positions of mutated residues in the context of the E. coli 70S ribosome structure (Protein Data Bank [PDB] entry 2AVY; [37]). Distance measurements are presented in Table S2 in the supplemental material, and potential structural effects are summarized in Table S3 in the supplemental material. S4 and S5 are located on the solvent side of the 30S subunit and share an extensive protein-protein interface (Fig. 5A). As in previous studies of ram mutations, a number of amino acid substitutions were found at the S4-S5 interface (Fig. 5B). These include S4 substitutions D49Y, Q53H, Q53P, E201G, S204T, K205E, and K205T and S5 substitutions K13M, I104L, E115Q, and N121H. Additional substitutions do not occur at the interface itself but are buried within the protein and probably affect S4-S5 interaction indirectly (Fig. 5C). These include S4 substitutions R69P, G86C, E196D, I199N, and L202F and S5 substitutions L75R, L80Q, T102I, and A109V. The nonsense mutations in S4, including those at E165, W169, E196, E201, and K205, cause loss of the C-terminal α-helix that is a major component of the S4-S5 interface. Consistent with the domain closure model, all five truncation mutants have a ribosomal-ambiguity phenotype.

FIG 5.

Prediction of structural effects of amino acid substitutions and termination mutants on the basis of the wild-type E. coli 70S ribosome crystal structure (36; PDB entries 2AVY and 2AW4). In all of the panels, S4 is blue, S5 is red, other ribosomal proteins are dark gray, and the 16S rRNA is light gray. (A) Surface representation of the solvent side of the 30S subunit showing the relative locations of ribosomal proteins S4 (pale green) and S5 (light blue). For orientation, the 50S subunit is shown as a transparent surface behind the 30S subunit. (B) Sites of amino acid substitutions in S4 and S5 identified in this study. The α carbons of residues mutated in restrictive and ram mutants are shown as yellow and red spheres, respectively. (C) Sites of substitutions potentially affecting the S4-S5 interface either directly by changing residues involved at the interface or indirectly by affecting the local S4 or S5 conformation. Positions in S4 from E165 to the C terminus are dark green, including the C-terminal α-helix at the S4-S5 interface. Mutated residues are shown as sticks. The 16S rRNA is white. (D) Proximity of 16S rRNA residues to the S4-S5 interface. (E) Sites of mutations potentially affecting S4-16S rRNA interactions distant from the S4-S5 interface. (F) Sites of mutations potentially affecting S5-16S rRNA interactions distant from the S4-S5 interface. The N134Y substitution affects the processing of the 16S rRNA.

Both S4 and S5 make direct contact with the 16S rRNA, including at the S4-S5 interface, and several amino acid substitutions could potentially perturb these interactions. Q96 of S5 is in position to hydrogen bond with A7 of the 16S rRNA (Fig. 5D); this base stacks on A298, consistent with the reported ribosomal-ambiguity phenotype of both A7G and G299A base substitutions (27). Several protein-RNA interactions are distant from the S4-S5 interface. Q151 of S4 is less than 4 Å from U437 at the base of 16S rRNA helix 17 (Fig. 5E), near the site of previously identified ram mutations at positions G423 and G424 (27). However, as the Q151P mutation was found only in combination with G86C, which alone produces a ribosomal-ambiguity phenotype, the influence of the Q151P mutation is not clear. E68 of S4 is within hydrogen bonding distance of both the phosphate oxygen of C545 at the base of 16S rRNA helix 18 and the hydroxyl group of Y203 of S4. The E68D mutation could thus perturb an rRNA contact and destabilize the local structure of S4. The adjacent R69 does not make any direct contacts, although the introduction of a rigidifying proline at this position could disrupt the local conformation of the α-helix and indirectly have the same effects as the E68D mutation.

S5 also makes contacts with 16S rRNA distant from the S4-S5 interface (Fig. 5F). Two of the S5 mutations, N134Y and L80Q, cause defects in 16S rRNA processing. These observations are consistent with the processing of 17S rRNA precursor occurring subsequent to the assembly of S5 into the 30S subunit (38). The phosphate oxygen of A19 is within hydrogen bonding distance of both S5-N134 and S5-S129, while the O4′ of G15 is within hydrogen bonding distance of the amino group of R28 of S5. 16S rRNA helix 1 residues A7 and G15 interact with S5 via contacts with R28 and Q96, respectively. In contrast, L80 of S5 is some 11 Å from 16S rRNA helix 1. However, it is buried within the S5 structure, and replacement of a hydrophobic side chain with a polar one could disrupt the structure and prevent stable interaction of the aforementioned residues with 16S rRNA. These observations suggest an important role for S5 in organizing the 5′ end of the 17S rRNA precursor for processing.

Several amino acid substitutions occur at sites interacting with other ribosomal proteins. For instance, G86 of S5 is on the protein surface, near sites of contact with protein S8, while E54 of S5 contacts K134 of S3. These substitutions suggest that the proper organization of S4 and S5 is essential for accurate decoding and is stabilized by a number of interactions with other components of the ribosome. While all deletion mutations and most substitutions produce a ribosomal-ambiguity phenotype, the S4-L202F substitution produces a restrictive phenotype. L202 is not in a position to contact S5 but is adjacent to two tyrosine residues, Y201 and Y50. In the context of the domain closure model, we would predict that this substitution would enhance S4-S5 interaction. Similarly, a restrictive phenotype is associated with the G86C substitution and would favor the closed conformation according to the domain closure model. The structures of these two mutants need to be determined to test this hypothesis.

The application of pre-steady-state kinetics and single-molecule fluorescence resonance energy transfer techniques has advanced our understanding of the individual steps of tRNA selection (39–41). Using fast kinetic approaches, Zaher and Green (31) showed, contrary to earlier studies, that ribosomes carrying an error-restrictive K42N substitution in S12 are altered in the proofreading step of selection, while ram ribosomes carrying a C-terminal deletion in S4 are impaired in the initial selection step. One interpretation of those authors is that disruption of the S4-S5 interface occurs during the initial selection step and S12's interaction with h27 and h44 of 16S rRNA occurs subsequently, during proofreading. This would mean that two structural rearrangements occur at distinct points on the selection pathway. However, at least some 16S rRNA mutations that promote miscoding, including G299A, which is close to S4 and S5, affect both the initial selection and proofreading steps of tRNA selection (42). Thus, it remains unclear whether the effects of altered S4 and S12 proteins on initial selection and proofreading, respectively, reflect distinct functional roles of these individual ribosomal proteins or unique properties of the characterized mutants. The many ram and restrictive S4, S5, S12, and rRNA alterations described here and in earlier studies (1, 15, 42, 43) provide some of the tools needed to test these and related models for tRNA selection.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are indebted to Philip Farabaugh for supplying the luciferase plasmids, to Sullivan Read for the use of a luminometer, to Somanon Bhattacharya for assistance with the figures, and to Jennifer Carr for her comments on the manuscript.

This work was supported by grants MCB0745025 from the National Science Foundation (to M.O.) and GM094157 from the National Institutes of Health (to S.T.G.).

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JB.02485-14.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dinman JD, O'Connor M. 2010. Mutants that affect recoding, p 321–344. In Atkins JF, Gesteland RF (ed), Recoding: expansion of decoding rules enriches gene expression. Springer, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gorini L, Jacoby GA, Breckenridge L. 1966. Ribosomal ambiguity. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol 31:657–664. doi: 10.1101/SQB.1966.031.01.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosset R, Gorini L. 1969. A ribosomal ambiguity mutation. J Mol Biol 39:95–112. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(69)90336-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parker J. 1989. Errors and alternatives in reading the universal genetic code. Microbiol Rev 53:273–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Piepersberg W, Bock A, Wittmann HG. 1975. Effect of different mutations in ribosomal protein S5 of Escherichia coli on translational fidelity. Mol Gen Genet 140:91–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00329777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ogle JM, Ramakrishnan V. 2005. Structural insights into translational fidelity. Annu Rev Biochem 74:129–177. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.061903.155440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ogle JM, Murphy FV, Tarry MJ, Ramakrishnan V. 2002. Selection of tRNA by the ribosome requires a transition from an open to a closed form. Cell 111:721–732. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)01086-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Björkman J, Samuelsson P, Andersson DI, Hughes D. 1999. Novel ribosomal mutations affecting translational accuracy, antibiotic resistance and virulence of Salmonella typhimurium. Mol Microbiol 31:53–58. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roy-Chaudhuri B, Kirthi N, Culver GM. 2010. Appropriate maturation and folding of 16S rRNA during 30S subunit biogenesis are critical for translational fidelity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:4567–4572. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912305107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vallabhaneni H, Farabaugh PJ. 2009. Accuracy modulating mutations of the ribosomal protein S4-S5 interface do not necessarily destabilize the rps4-rps5 protein-protein interaction. RNA 15:1100–1109. doi: 10.1261/rna.1530509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fagan CE, Dunkle JA, Maehigashi T, Dang MN, Devaraj A, Miles SJ, Qin D, Fredrick K, Dunham CM. 2013. Reorganization of an intersubunit bridge induced by disparate 16S ribosomal ambiguity mutations mimics an EF-Tu-bound state. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110:9716–9721. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1301585110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moore PB. 2013. Ribosomal ambiguity made less ambiguous. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110:9627–9628. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1307288110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DeWilde M, Wittmann-Liebold B. 1973. Localization of the amino-acid exchange in protein S5 from an Escherichia coli mutant resistant to spectinomycin. Mol Gen Genet 127:273–276. doi: 10.1007/BF00333767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yaguchi M, Wittmann HG, Cabezon T, De Wilde M, Villarroel R, Herzog A, Bollen A. 1975. Cooperative control of translational fidelity by ribosomal proteins in Escherichia coli. II. Localization of amino acid replacements in proteins S5 and S12 altered in double mutants resistant to neamine. Mol Gen Genet 142:35–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Agarwal D, Gregory ST, O'Connor M. 2011. Error-prone and error-restrictive mutations affecting ribosomal protein S12. J Mol Biol 410:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.04.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O'Connor M, Gregory ST. 2011. Inactivation of the RluD pseudouridine synthase has minimal effects on growth and ribosome function in wild-type Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica. J Bacteriol 193:154–162. doi: 10.1128/JB.00970-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Datsenko KA, Wanner BL. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97:6640–6645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120163297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sun Q, Vila-Sanjurjo A, O'Connor M. 2011. Mutations in the intersubunit bridge regions of 16S rRNA affect decoding and subunit-subunit interactions on the 70S ribosome. Nucleic Acids Res 39:3321–3330. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wachi M, Umitsuki G, Shimizu M, Takada A, Nagai K. 1999. Escherichia coli cafA gene encodes a novel RNase, designated as RNase G, involved in processing of the 5′ end of 16S rRNA. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 259:483–488. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hayes F, Vasseur M. 1976. Processing of the 17-S Escherichia coli precursor RNA in the 27-S pre-ribosomal particle. Eur J Biochem 61:433–442. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1976.tb10037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harvey RJ, Koch AL. 1980. How partially inhibitory concentrations of chloramphenicol affect the growth of Escherichia coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 18:323–337. doi: 10.1128/AAC.18.2.323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kramer EB, Farabaugh PJ. 2007. The frequency of translational misreading errors in E. coli is largely determined by tRNA competition. RNA 13:87–96. doi: 10.1261/rna.294907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O'Connor M, Thomas CL, Zimmermann RA, Dahlberg AE. 1997. Decoding fidelity at the ribosomal A and P sites: influence of mutations in three different regions of the decoding domain in 16S rRNA. Nucleic Acids Res 25:1185–1193. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.6.1185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dahlgren A, Ryden-Aulin M. 2000. A novel mutation in ribosomal protein S4 that affects the function of a mutated RF1. Biochimie 82:683–691. doi: 10.1016/S0300-9084(00)01160-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cabezon T, Herzog A, De Wilde M, Villarroel R, Bollen A. 1976. Cooperative control of translational fidelity by ribosomal proteins in Escherichia coli. III. A ram mutation in the structural gene for protein S5 (rpx E). Mol Gen Genet 144:59–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bollen A, Davies J, Ozaki M, Mizushima S. 1969. Ribosomal protein conferring sensitivity to the antibiotic spectinomycin in Escherichia coli. Science 165:85–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McClory SP, Leisring JM, Qin D, Fredrick K. 2010. Missense suppressor mutations in 16S rRNA reveal the importance of helices h8 and h14 in aminoacyl-tRNA selection. RNA 16:1925–1934. doi: 10.1261/rna.2228510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Olsson M, Isaksson L, Kurland CG. 1974. Pleiotropic effects of ribosomal protein s4 studied in Escherichia coli mutants. Mol Gen Genet 135:191–202. doi: 10.1007/BF00268615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mayerle M, Woodson SA. 2013. Specific contacts between protein S4 and ribosomal RNA are required at multiple stages of ribosome assembly. RNA 19:574–585. doi: 10.1261/rna.037028.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li Z, Pandit S, Deutscher MP. 1999. RNase G (CafA protein) and RNase E are both required for the 5′ maturation of 16S ribosomal RNA. EMBO J 18:2878–2885. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.10.2878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zaher HS, Green R. 2010. Hyperaccurate and error-prone ribosomes exploit distinct mechanisms during tRNA selection. Mol Cell 39:110–120. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Andersson DI, Kurland CG. 1983. Ram ribosomes are defective proofreaders. Mol Gen Genet 191:378–381. doi: 10.1007/BF00425749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maisnier-Patin S, Berg OG, Liljas L, Andersson DI. 2002. Compensatory adaptation to the deleterious effect of antibiotic resistance in Salmonella typhimurium. Mol Microbiol 46:355–366. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Henkin TM, Chambliss GH, Grundy FJ. 1990. Bacillus subtilis mutants with alterations in ribosomal protein S4. J Bacteriol 172:6380–6385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Inaoka T, Kasai K, Ochi K. 2001. Construction of an in vivo nonsense readthrough assay system and functional analysis of ribosomal proteins S12, S4, and S5 in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 183:4958–4963. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.17.4958-4963.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wittmann-Liebold B, Greuer B. 1978. The primary structure of protein S5 from the small subunit of the Escherichia coli ribosome. FEBS Lett 95:91–98. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(78)80059-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schuwirth BS, Borovinskaya MA, Hau CW, Zhang W, Vila-Sanjurjo A, Holton JM, Cate JH. 2005. Structures of the bacterial ribosome at 3.5 A resolution. Science 310:827–834. doi: 10.1126/science.1117230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang Z, Guo Q, Goto S, Chen Y, Li N, Yan K, Zhang Y, Muto A, Deng H, Himeno H, Lei J, Gao N. 2014. Structural insights into the assembly of the 30S ribosomal subunit in vivo: functional role of S5 and location of the 17S rRNA precursor sequence. Protein Cell 5:394–407. doi: 10.1007/s13238-014-0044-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zaher HS, Green R. 2009. Fidelity at the molecular level: lessons from protein synthesis. Cell 136:746–762. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rodnina MV, Gromadski KB, Kothe U, Wieden HJ. 2005. Recognition and selection of tRNA in translation. FEBS Lett 579:938–942. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.11.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Johansson M, Lovmar M, Ehrenberg M. 2008. Rate and accuracy of bacterial protein synthesis revisited. Curr Opin Microbiol 11:141–147. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2008.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McClory SP, Devaraj A, Fredrick K. 2014. Distinct functional classes of ram mutations in 16S rRNA. RNA 20:496–504. doi: 10.1261/rna.043331.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Agarwal D, O'Connor M. 2014. Diverse effects of residues 74-78 in ribosomal protein S12 on decoding and antibiotic sensitivity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 445:475–479. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.