Abstract

Objective

Providers and patients are most likely to use and benefit from guidelines accompanied by implementation support. Guidelines published in 2007 and earlier assessed with the Appraisal of Guidelines, Research and Evaluation (AGREE) instrument scored poorly for applicability, which reflects the inclusion of implementation instructions or tools. The purpose of this study was to examine the applicability of guidelines published in 2008 or later and identify factors associated with applicability.

Design

Systematic review of studies that used AGREE to assess guidelines published in 2008 or later.

Data sources

MEDLINE and EMBASE were searched from 2008 to July 2014, and the reference lists of eligible items. Two individuals independently screened results for English language studies that reviewed guidelines using AGREE and reported all domain scores, and extracted data. Descriptive statistics were calculated across all domains. Multilevel regression analysis with a mixed effects model identified factors associated with applicability.

Results

Of 245 search results, 53 were retrieved as potentially relevant and 20 studies were eligible for review. The mean and median domain scores for applicability across 137 guidelines published in 2008 or later were 43.6% and 42.0% (IQR 21.8–63.0%), respectively. Applicability scored lower than all other domains, and did not markedly improve compared with guidelines published in 2007 or earlier. Country (UK) and type of developer (disease-specific foundation, non-profit healthcare system) appeared to be associated with applicability when assessed with AGREE II (not original AGREE).

Conclusions

Despite increasing recognition of the need for implementation tools, guidelines continue to lack such resources. To improve healthcare delivery and associated outcomes, further research is needed to establish the type of implementation tools needed and desired by healthcare providers and consumers, and methods for developing high-quality tools.

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study found that, among 137 guidelines published from 2008 to 2013 described in systematic reviews published from 2010 to 2014, the mean and median domain scores for applicability were 43.6% and 42.0%, respectively, and applicability scored lower than the other five Appraisal of Guidelines, Research and Evaluation (AGREE) domains.

Applicability of guidelines, which refers to the inclusion of implementation instructions and tools, did not improve subsequent to the publication of two similar meta-reviews in 2010 and 2012, respectively, which examined a total of 654 guidelines published from 1980 to 2007.

Country (UK) and type of developer (disease-specific foundation, non-profit healthcare system) appeared to be associated with applicability when assessed using AGREE II (not original AGREE) though these findings should be interpreted with caution.

Our literature search may not have identified all relevant studies, the AGREE instrument may not objectively appraise guidelines, or high AGREE scores may not be a determinant of guideline use; therefore, further research is needed to identify strategies that promote and support the development of guideline implementation tools.

Background

Guidelines play a fundamental role in healthcare planning, delivery, evaluation and quality improvement. However, they are not consistently translated into policy or practice.1–3 Interviews with users found they were frustrated with the vast number of guidelines and uncertain about how to implement them given numerous interacting contextual challenges.4–6 Greenhalgh et al7 described this as an evidence-based medicine ‘crisis’ and called for guideline-based tools that could be used by providers and patients to clarify the goals of care, quality and completeness of evidence, and relevance of potential benefits and harms. Pronovost8 also advocated for the development of implementation tools such as instructions for assessing barriers and choosing corresponding implementation strategies, and point-of-care checklists that integrate recommendations for patients with comorbid conditions.

Considerable evidence supports the assertion that guidelines featuring implementation instructions or tools such as those recommended by Greenhalgh et al7 and Pronovost8 are more likely to be used.9–11 For example, a systematic review of 68 studies of provider adherence to asthma guidelines found that decision support tools (electronic or paper-based guideline summaries, algorithms, history-taking template, asthma status reminders) increased prescribing and provision of patient self-education or action plans, and was the only intervention studied that reduced emergency department visits.9 A Cochrane systematic review of eight studies found that mailing of print summaries improved compliance with care delivery recommendations.10 A systematic review of 100 randomised/non-randomised studies involving 3826 practitioners/practices caring for more than 92 895 patients found that nearly two-thirds of studies resulted in improved guideline adherence for diagnosis, prevention, disease management and prescribing.11

The Appraisal of Guidelines, Research and Evaluation (AGREE) instrument and its revised version, AGREE II, can be used to develop or appraise guidelines and related material in separate documents that may be published or publicly available on websites.12 13 AGREE II consists of 23 items grouped in six domains: scope and purpose, stakeholder involvement, rigour of development, clarity and presentation, applicability and editorial independence.13 The domain of applicability includes four items related to planning, undertaking and evaluating implementation—facilitators and barriers of guideline implementation, resource considerations, monitoring or audit criteria, and implementation instructions or tools similar to those recommended by Greenhalgh et al7 and Pronovost,8 and for which there is evidence of association with guideline use.9–11 A metareview by Alonso-Coello et al14 of 42 studies in which 626 guidelines on a range of topics published in various countries from 1980 to 2007 were assessed with AGREE found that most guidelines scored low for applicability (mean 22%, 95% CI 20.4% to 23.9%) relative to all other domains. Another meta-review by Knai et al15 of 28 European guidelines on a range of topics published from 2000 to 2007 similarly found that most guidelines scored low for applicability (mean 44%, range 0–100%) relative to all domains but editorial independence. Although scoring reflects all domain items, not only the presence of implementation tools, the finding that applicability consistently scored lower than other domains across multiple years and types of guidelines is striking.

Limited use of guidelines contributes to omission of beneficial therapies, preventable harm, suboptimal patient outcomes or experiences, or waste of resources.7 8 Alonso-Coello et al14 and Knai et al15 showed that few guidelines featured implementation tools, which improve guideline use, but both studies were based on guidelines published in 2007 or earlier. This study reviewed the applicability of guidelines published in 2008 or later given emerging views and evidence regarding the need for implementation tools. A secondary purpose was to identify factors associated with applicability. The findings may reveal whether additional guidance is needed to promote the development of guideline implementation tools, thereby enabling guideline use, and improved care delivery and associated outcomes.

Methods

Approach

We conducted a meta-review of studies that used the original AGREE instrument or AGREE II (henceforth referred to collectively as AGREE) to evaluate the quality of guidelines. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) criteria guided reporting of the methods and findings (etable 1).16 A protocol was not registered and ethics review was not required.

Searching and screening

MEDLINE and EMBASE were searched from 2008 to July 2014 for English language studies that assessed guidelines using AGREE. The search strategy (box 1) was based on terms used to index previous meta-reviews.14 15 The references of all eligible studies were also screened. Titles and abstracts of search results were reviewed independently by the principal investigator and a trained research assistant. All items selected by at least one reviewer were retrieved for further assessment. Studies were eligible if they were systematic reviews, one or more of the guidelines they evaluated were published in 2008 or later, guidelines were assessed by at last two reviewers, scores for all AGREE domains were reported and either domain score, or scores for individual items such that domain score could be calculated, were reported for each guideline. Eligible studies reviewed all guidelines in a particular country, or all guidelines on a particular topic, clinical condition or type of patient management. Studies were not eligible if they compared guideline content only (eg, underlying evidence, development methods or recommendations across guidelines) and did not report domain scores; evaluations served as a baseline needs assessment in a country new to guideline development since they had not yet developed capacity for generating guidelines; or guidelines were sampled from and assessed by the same organisation since this would not reflect a range of factors of interest that might influence applicability, and potentially bias the assessment. Studies in the form of abstracts, letters, commentaries or editorials were not eligible.

Box 1. Literature search strategy. Database: Ovid MEDLINE(R) without Revisions <1996 to June Week 2 2014> Search Strategy:

1. Practice Guidelines as Topic/st [Standards] (5129)

2. Quality control/ (27721)

3. AGREE.mp. (14714)

4. 2 or 3 (42328)

5. 1 and 4 (204)

6. Limit 5 to (English language and yr=“2008-Current)” (117)

7. Limit 6 to (comment or editorial or interview or lectures or letter or news) (15)

8. 6 not 7 (102)

Data collection and analysis

There are frameworks that identify multiple, often interacting factors that influence guideline use,4–6 but there are no frameworks that identify why some guidelines and not others feature implementation tools. We postulated that type of developer, nature or complexity of guideline topic, year produced or AGREE version may have influenced decisions about whether to develop implementation tools. For eligible reviews, data were collected on year published, clinical topic, version of AGREE, range of years during which guidelines were published, number of guidelines appraised and number of guidelines appraised that were published in 2008 or later. For individual guidelines published in 2008 or later included in eligible reviews, data were collected on date published, country, type of developer (professional organisation, disease-specific organisation, government agency, non-profit agency, healthcare system, academic organisation), AGREE version and domain scores. Data were extracted and tabulated by the principal investigator, then independently reviewed by the research assistant. Descriptive statistics were calculated for all domains (mean, median, range, IQR). We tested the association between applicability score and guideline publication date, country and type of developer using mixed effect models accounting for the review source as a nested variable. A secondary analysis was conducted testing the association between applicability and the covariates using the same statistical procedure stratified by AGREE. We used SAS V.9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA) to conduct the analysis. All p values were two-sided and reported as being statistically significant on the basis of a significance level of 0.05. The methodological quality of eligible studies was not scored since AMSTAR is appropriate for assessing systematic reviews of randomised controlled trials.17 However, most of its 11 items (items 1, 2, 5–9) were screening criteria and therefore present across all studies.

Results

Study characteristics

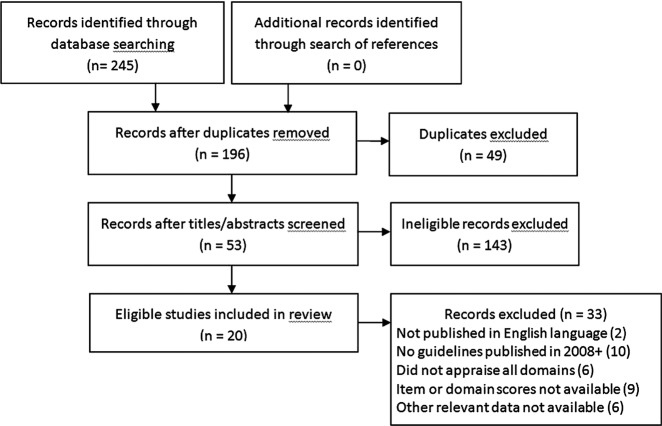

The search resulted in 245 articles; 53 were retrieved and 20 were eligible for review (figure 1). Studies were published from 2010 to 2014 and reviewed 254 guidelines (range 5–24) published from 1992 to 2013 on numerous topics (table 1).18–37 Guidelines were appraised with the original AGREE instrument in 9 studies and AGREE II in 11 studies. Of the guidelines included in eligible studies, 137 were published in 2008 or later.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram.

Table 1.

Characteristics of eligible studies

| Study | Clinical topic | AGREE version | Number of guidelines | Publication date of guidelines | Number of guidelines published 2008+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lee et al18 | Acute procedural pain, paediatrics | 2 | 18 | 2001 to 2013 | 12 |

| Nuckols et al19 | Opioid use for chronic pain | 2 | 13 | 2009 to 2012 | 12 |

| Sabharwal et al20 | Orthopaedic thromboprophylaxis | 2 | 7 | 2009 to 2013 | 7 |

| Larmer et al21 | Management of osteoarthritis | 2 | 19 | 2001 to 2013 | 11 |

| Lytras et al22 | Occupational asthma | 2 | 7 | 1992 to 2012 | 3 |

| Al-Ansary et al23 | Hypertension | 2 | 11 | 2006 to 2011 | 8 |

| Holmer et al24 | Glycaemic control type 2 diabetes | 2 | 24 | 2007 to 2012 | 19 |

| Lopez-Vargas et al25 | Chronic kidney disease | 2 | 11 | 2002 to 2011 | 6 |

| Rohde et al26 | Aphasia in stroke management | 2 | 19 | 2001 to 2010 | 13 |

| Greuter et al27 | Diabetes in pregnancy | 1 | 8 | 2003 to 2010 | 5 |

| Arevalo-Rodriguez et al28 | Dementia in Alzheimer’s disease | 2 | 15 | 2005 to 2011 | 9 |

| Seixas et al29 | Management of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder | 1 | 13 | 2001 to 2011 | 3 |

| Pillastrini et al30 | Management of low back pain in primary care | 1 | 13 | 2002 to 2009 | 3 |

| Tong et al31 | Screening and follow-up of living kidney donors | 2 | 10 | 1996 to 2010 | 3 |

| De Hert et al32 | Screening and monitoring of cardiometabolic risk in schizophrenia | 1 | 18 | 2004 to 2010 | 7 |

| Hurkmans et al33 | Physiotherapy use in rheumatoid arthritis | 1 | 8 | 2002 to 2009 | 2 |

| Fortin et al34 | Chronic conditions relevant to primary care | 1 | 16 | 2003 to 2009 | 4 |

| Tan et al35 | Psoriasis vulgaris | 1 | 8 | 2007 to 2009 | 7 |

| McNair and Hegarty36 | Primary care of lesbian, gay and bisexual people | 1 | 11 | 1997 to 2010 | 2 |

| Mahmud and Mazza37 | Preconception care of women with diabetes | 1 | 5 | 2001 to 2009 | 2 |

AGREE, Appraisal of Guidelines, Research and Evaluation.

Guideline characteristics

Of 137 guidelines, 33 (24.1%) were published in 2008, 37 (27.0%) in 2009, 28 (20.4%) in 2010, 22 (16.1%) in 2011, 14 (10.2%) in 2012 and 3 (2.2%) in 2013. Almost half were published by professional associations or societies (67, 48.9%). The remaining guidelines were published by government agencies (36, 26.3%), disease-specific organisations (16, 11.7%), non-profit health delivery systems (10, 7.3%), academic organisations (7, 5.1%) and one by the WHO. Most guidelines were developed in the USA (46, 33.6%), UK (25, 18.2%) and Canada (20, 14.6%), and 13 (9.5%) by international groups. Several countries produced one or more guidelines included in the sample, including Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Finland, France, Italy, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, South Africa, Spain, Sweden and Turkey. Most guidelines were appraised using AGREE II (103, 75.2%).

Applicability scores

Table 2 summarises scores for all AGREE domains. The mean and median domain scores for applicability across all guidelines were 43.6% and 42.0%, respectively. These were lower than the mean and median of all other domains for guidelines in the sample. These results are higher than those reported by Alonso-Coello et al14 (mean 22%, 95% CI 20.4% to 23.9%) and similar to the findings of Knai et al15 (mean 44%, range 0–100%). The spread across range and IQR for each domain shows that scores for all domains were inconsistent across guidelines but more so for editorial independence, rigour of development, then applicability, followed by remaining domains.

Table 2.

Domain scores for guidelines published in 2008 or later

| AGREE domain scores (%) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data | Scope and purpose | Stakeholder involvement | Rigour of development | Clarity of presentation | Applicability | Editorial independence |

| Mean | 73.9 | 55.00 | 57.3 | 76.3 | 43.6 | 48.8 |

| Median | 78.0 | 53.0 | 57.3 | 83.0 | 42.0 | 50.0 |

| Range | 6.0 to 100.0 | 8.0 to 100.0 | 0.0 to 100.0 | 14.0 to 100.0 | 0.0 to 100.0 | 0.0 to 100.0 |

| IQR (difference) | 61.1 to 94.0 (32.9) | 39.0 to 73.0 (34.0) | 31.0 to 81.0 (50.0) | 64.0 to 91.7 (27.7) | 21.8 to 63.0 (41.2) | 12.5 to 79.0 (66.5) |

AGREE, Appraisal of Guidelines, Research and Evaluation

Factors influencing applicability

An analysis of factors associated with applicability appears in table 3. The estimated intraclass correlation was 0.47. Applicability mean score differed by year of guideline publication. Guidelines published in 2010 and 2012 were associated with higher applicability score than those published in 2013. The differences in mean applicability score for 2010 and 2012, were 26.5 (p<0.03) and 28.3 (p<0.02), respectively. With respect to country, the highest mean applicability score was for guidelines developed in the UK. Guidelines developed by international groups, in Canada or the USA had significantly lower applicability scores compared with the UK. As for type of developer, disease-specific foundations and non-profit healthcare systems were associated with higher applicability scores than professional guideline developers. Mean applicability score differences were 16.2 (p=0.01) and 14.9 (p<0.04), respectively. When stratified by version of the AGREE instrument, 34 studies were included in the analysis for AGREE and 103 for AGREE II. The association between applicability score, year, country and type of guideline developer remained significant for AGREE II only and not for AGREE (data not shown).

Table 3.

Observed, adjusted and mean applicability score difference using mixed effect model controlling for publication year, country and type of guideline developer nested within the review source, 2008–2013

| Factor | Observed mean applicability score | Adjusted mean applicability score (95% CI) |

Mean applicability score difference | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Guideline publication year | ||||

| 2008 | 47.0 | 47 (33.2 to 60.7) | 24.0 | 0.48 |

| 2009 | 47.7 | 45.8 (32.1 to 59.5) | 22.8 | 0.06 |

| 2010 | 47.7 | 49.5 (36.0 to 63.0) | 26.5 | 0.03* |

| 2011 | 31.1 | 41.3 (26.6 to 55.9) | 18.3 | 0.14 |

| 2012 | 41.9 | 51.3 (35.2 to 67.4) | 28.3 | 0.02* |

| 2013 | 16.3 | 23 (−3.1 to 49.1) | Reference | |

| Country | ||||

| International group | 35.9 | 35.7 (21.9 to 49.4) | −26.1 | <0.001* |

| Canada | 47.9 | 42.0 (26.7 to 57.3) | −19.8 | <0.001* |

| USA | 38.6 | 32.3 (18.2 to 46.4) | −29.5 | <0.001* |

| UK | 64.4 | 61.8 (46.3 to 77.3) | Reference | |

| Type of guideline developer | ||||

| Disease-specific foundation | 50.0 | 56.5 (42.7 to 70.3) | 16.2 | 0.01* |

| Non-profit healthcare system | 49.7 | 55.2 (38.5 to 71.9) | 14.9 | 0.04* |

| Government agency | 48.1 | 44.4 (31.4 to 57.4) | 4.1 | 0.4 |

| Academic organisation | 40.7 | 53.6 (34.1 to 73.1) | 13.3 | 0.14 |

| Professional organisation | 39.7 | 40.3 (28.7 to 51.9) | Reference | |

*All p values two-sided, significance level 0.05.

Discussion

Providers and patients are most likely to benefit from guidelines featuring implementation tools.5 6 9–11 The applicability of guidelines published in 2008 or later has not markedly improved compared with guidelines published in 2007 or earlier, did not increase over time from 2008 to 2013 and remains low compared with other AGREE domains.14 15 Guidelines published in the UK, or by disease-specific foundations or non-profit healthcare systems, appeared to be associated with higher applicability scores, though only when assessed using AGREE II. These findings are of concern given the intensity and cost of efforts to generate an ever-increasing body of guidelines that are not used. Although multiple factors other than implementation tools influence guideline use, including patient, provider, institutional and system-level issues, implementation tools are meant to overcome many of these barriers.4–6 Furthermore, guideline developers, implementers and researchers said that, in comparison with other approaches for implementing guidelines, developing implementation tools was more feasible, could be widely applied and was therefore more likely to impact guideline use.38

Several issues may limit the interpretation and use of these findings. The literature search may not have identified all relevant studies; however, we searched the two most relevant medical databases, and screening and data extraction were undertaken independently by two individuals to improve reliability. We relied on published meta-reviews, so the sample of guidelines was non-random. However, eligible studies included 137 guidelines published in 2008 or later with a variety of characteristics, so the findings may be generalisable across other guidelines. Others have noted several limitations of the AGREE instrument that was used to score guidelines in eligible studies.17 For example, scoring of domain items can be subjective, and domain or overall score has not been definitively associated with guideline use. With respect to applicability, this information may be more likely found outside the guideline document compared with content reflecting other domains, rendering an assessment of applicability more challenging. However, AGREE remains the internationally accepted gold standard for appraising guidelines. It is notable that associations between applicability scores and other factors were revealed by AGREE II13 in which the definition and instructions for scoring of applicability were elaborated on compared with the original AGREE instrument.12 While this study found that country (UK) and type of developer (disease-specific foundation, non-profit healthcare system) were associated with applicability score, the finding may not be meaningful, in part because all non-profit healthcare systems were located in the US and not the UK, and because fewer guidelines were produced by non-professional organisations. However, this study was exploratory in nature and examined preliminary hypotheses, so ongoing research is needed to investigate the influence of these, and other factors, perhaps by repeating the same analysis once more meta-reviews were published. Alternatively, further investigation of other factors, for example, the characteristics and workflow of the intended users of these guidelines, may provide some insight on why implementation tools were created for these guidelines. Despite these potential limitations, this study underscores the urgent need to create impetus and guidance that would support the development of guideline implementation tools.

AGREE and other initiatives such as Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) system and the GuideLine Implementability Appraisal (GLIA) instrument have improved the description of guideline methods, evidence and recommendations.39 40 However, there has been far less scrutiny of accompanying implementation tools. We interviewed international guideline developers who said there was a demand for such resources among their constituents but they required guidance for developing implementation tools.38 We and others analysed guideline development and implementation instructional manuals and found that they lacked guidance for developing implementation tools.41 42 Therefore, we consulted with members of the international guideline community to generate a 12-item framework that can serve as the basis for evaluating and endorsing or adapting existing guideline implementation tools, or developing new tools.43

Additional research is needed to examine the type of tools that are most needed and preferred by different types of guideline users, the types of implementation tools best suited for different guidelines and the features of implementation tools that are associated with guideline use. Pronovost8 noted that developers may lack relevant expertise to develop implementation tools and encouraged them to partner with others such as implementation or social scientists. Coordinating complex, protracted partnerships involving numerous stakeholders with differing interests can be challenging.44 45 However, the Choosing Wisely initiative, in which numerous specialty societies and consumer groups partnered to develop shared decision-making tools, demonstrates that partnership is indeed possible when there is a widely recognised need for improvement.46 Still, further research is needed to identify the capacity, including skills and resources needed to develop implementation tools.

Footnotes

Contributors: ARG and MCB conceived the study, interpreted data, drafted the manuscript and approved the final version of this manuscript. ARG was responsible for collecting and analysing data. Both authors agree to be accountable for the work, and to provide data on which the manuscript was based. This research was conducted without peer-reviewed funding. All authors, external and internal, had full access to all of the data (including statistical reports and tables) in the study and can take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All relevant data are available in the manuscript and online supplementary files.

References

- 1.McGlynn EA, Asch SM, Adams J et al. . The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. NEJM 2003;348:2635–45. 10.1056/NEJMsa022615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sheldon TA, Cullum N, Dawson D et al. . What's the evidence that NICE guidance has been implemented? Results from a national evaluation using time series analysis, audit of patients’ notes, and interviews. BMJ 2004;329:999 10.1136/bmj.329.7473.999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Runciman WB, Hunt TD, Hannaford NA et al. . CareTrack: assessing the appropriateness of health care delivery in Australia. Med J Aust 2012;197:100–5. 10.5694/mja12.10510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Francke AL, Smit MC, de Veer AJ et al. . Factors influencing the implementation of clinical guidelines for health care professionals. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2008;8:38 10.1186/1472-6947-8-38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mickan S, Burls A, Glasziou P. Patterns of “leakage” in the utilization of clinical guidelines: a systematic review. Postgrad Med J 2011;87:670–9. 10.1136/pgmj.2010.116012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McKillop A, Crisp J, Walsh K. Practice guidelines need to address the “how” and the “what” of implementation. Prim Health Care Res Dev 2012;13:48–59. 10.1017/S1463423611000405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greenhalgh T, Howick J, Maskrey N; for the Evidence Based Renaissance Group. Evidence based medicine: a movement in crisis? BMJ 2014;348:g37225 10.1136/bmj.g3725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pronovost PJ. Enhancing physicians’ use of clinical guidelines. JAMA 2013;310:2501–2. 10.1001/jama.2013.281334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Okelo SO, Butz AM, Sharma R et al. . Interventions to modify health care provider adherence to asthma guidelines: a systematic review. Pediatrics 2013;132:517–34. 10.1542/peds.2013-0779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murthy L, Shepperd S, Clarke MJ et al. . Interventions to improve the use of systematic reviews in decision-making by health system managers, policy makers and clinicians. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;9:CD009401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garg AX, Adhikari NK, McDonald H et al. . Effects of computerized clinical decision support systems on practitioner performance and patient outcomes. JAMA 2005;293:1223–38. 10.1001/jama.293.10.1223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cluzeau F, Burgers J, Brouwers M et al. . Development and validation of an international appraisal instrument for assessing the quality of clinical practice guidelines: the AGREE project. Qual Saf Health Care 2003;12:18–23. 10.1136/qhc.12.1.18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brouwers M, Kho ME, Browman GP et al. . AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in healthcare. CMAJ 2010;182:e839–842. 10.1503/cmaj.090449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alonso-Coello P, Irfan A, Sola I et al. . The quality of clinical practice guidelines over the last two decades: a systematic review of guideline appraisal studies. Qual Saf Health Care 2010;19:e58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Knai C, Brusamento S, Legido-Quigley H et al. . Systematic review of the methodological quality of clinical guideline development for the management of chronic disease in Europe. Health Policy 2012;107:157–67. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2012.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J et al. ; The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009;339:b2535 10.1136/bmj.b2535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shea BJ, Grimshaw JM, Wells GA et al. . Development of AMSTAR: a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 2007;7:10 10.1186/1471-2288-7-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee GY, Yamada J, Kyololo O et al. . Pediatric clinical practice guidelines for acute procedural pain: a systematic review. Pediatrics 2014;133:500–15. 10.1542/peds.2013-2744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nuckols TK, Anderson L, Popescu I et al. . Opioid prescribing: a systematic review and critical appraisal of guidelines for chronic pain. Ann Intern Med 2014;160:38–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sabharwal S, Gauher S, Kyriacou S et al. . Quality assessment of guidelines on thromboprophylaxis in orthopaedic surgery. Bone Joint J 2014;96:19–23. 10.1302/0301-620X.96B1.32943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Larmer PJ, Reay ND, Aubert ER et al. . Systematic review of guidelines for the physical management of osteoarthritis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2014;95:375–89. 10.1016/j.apmr.2013.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lytras T, Bonovas S, Chronis C et al. . Occupational asthma guidelines: a systematic quality appraisal using the AGREE II instrument. Occup Environ Med 2014;71:81–6. 10.1136/oemed-2013-101656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Al-Ansary LA, Tricco AC, Adi Y et al. . A systematic review of recent clinical practice guidelines on the diagnosis, assessment and management of hypertension. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e53744 10.1371/journal.pone.0053744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holmer HK, Ogden LA, Burda BU et al. . Quality of clinical practice guidelines for glycemic control in type 2 diabetes mellitus. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e58625 10.1371/journal.pone.0058625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lopez-Vargas PA, Tong A, Sureshkumar P et al. . Prevention, detection and management of early chronic kidney disease: a systematic review of clinical practice guidelines. Nephrology 2013;18:592–604. 10.1111/nep.12119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rohde A, Worrall L, Le Dorze G. Systematic review of the quality of clinical guidelines for aphasia in stroke management. J Eval Clin Pract 2013;19:994–1003. 10.1111/jep.12023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Greuter MJ, van Emmerik NM, Wouters MG et al. . Quality of guidelines on the management of diabetes in pregnancy: a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2012;12:58 10.1186/1471-2393-12-58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arevalo-Rodriguez I, Pedraza OL, Rodriguez A et al. . Alzheimer's disease dementia guidelines for diagnostic testing: a systematic review. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 2012;28:111–19. 10.1177/1533317512470209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seixas M, Weiss M, Muller U. Systematic review of national and international guidelines on attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Psychopharmacol 2012;26:753–65. 10.1177/0269881111412095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pillastrini P, Gardenghi I, Bonetti F et al. . An updated overview of clinical guidelines for chronic low back pain management in primary care. Joint Bone Spine 2012;79:176–85. 10.1016/j.jbspin.2011.03.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tong A, Chapman JR, Wong G et al. . Screening and follow-up of living kidney donors: a systematic review of clinical practice guidelines. Transplantation 2011;92:962–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.De Hert M, Vancampfort D, Correll CU et al. . Guidelines for screening and monitoring of cardiometabolic risk in schizophrenia: systematic evaluation. Br J Psychiatry 2011;199:99–105. 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.084665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hurkmans EJ, Jones A, Li LC et al. . Quality appraisal of clinical practice guidelines on the use of physiotherapy in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. Rheumatology 2011;50:1879–88. 10.1093/rheumatology/ker195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fortin M, Contant E, Savard C et al. . Canadian guidelines for clinical practice: an analysis of their quality and relevance to the care of adults with comorbidity. BMC Fam Pract 2011;12:74 10.1186/1471-2296-12-74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tan JK, Wolfe BJ, Bulatovic R et al. . Critical appraisal of quality of clinical practice guidelines for treatment of psoriasis vulgaris, 2006–2009. J Invest Dermatol 2010;130:2389–95. 10.1038/jid.2010.164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McNair RP, Hegarty K. Guidelines for the primary care of lesbian, gay and bisexual people: a systematic review. Ann Fam Med 2010;8:533–41. 10.1370/afm.1173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mahmud M, Mazza D. Preconception care of women with diabetes: a review of current guideline recommendations. BMC Womens Health 2010;10:5 10.1186/1472-6874-10-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gagliardi AR. “More bang for the buck”: exploring optimal approaches for guideline implementation through interviews with international developers. BMC Health Serv Res 2012;12:404 10.1186/1472-6963-12-404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schunemann HJ, Oxman AD, Brozek J et al. . GRADE: assessing the quality of evidence for diagnostic recommendations. Evid Based Med 2008;13:162–3. 10.1136/ebm.13.6.162-a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shiffman RN, Dixon J, Brandt C et al. . The GuideLine Implementability Appraisal (GLIA): development of an instrument to identify obstacles to guideline implementation. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2005;5:23 10.1186/1472-6947-5-23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gagliardi AR, Brouwers MC. Integrating guideline development and implementation: analysis of guideline development manual instructions for generating implementation advice. Implement Sci 2012;7:67 10.1186/1748-5908-7-67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schunemann HJ, Wiercioch W, Etxeandia I et al. . Guidelines 2.0: systematic development of a comprehensive checklist for a successful guideline enterprise. CMAJ 2014;186:E123–142. 10.1503/cmaj.131237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gagliardi AR, Brouwers MC, Bhattacharyya O. A framework of the desirable features of guideline implementation tools (GItools): Delphi survey and assessment of GItools. Implement Sci 2014;9:98 10.1186/s13012-014-0098-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.King G, Currie M, Smith L et al. . A framework of operating models for interdisciplinary research programs in clinical service organizations. Eval Program Plann 2008;31:160–73. 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2008.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hall JG, Buchan A, Cribb A et al. . A meeting of the minds: interdisciplinary research in the health sciences in Canada. CMAJ 2006;175:763–71. 10.1503/cmaj.060783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.2013. Choosing Wisely: an initiative of the ABIM Foundation. http://www.choosingwisely.org.