Abstract

Objectives

Physicians are a commonly targeted group in health research surveys, but their response rates are often relatively low. The goal of this paper was to evaluate the effect of unconditional incentives in the form of a coffee card on physician postal survey response rates.

Design

Following 13 key informant interviews and eight cognitive interviews a survey questionnaire was developed.

Participants

A random sample of 534 physicians, stratified by physician group (geriatricians, family physicians, emergency physicians) was selected from a national medical directory.

Setting

Using computer generated random numbers; half of the physicians in each stratum were allocated to receive a coffee card to a popular national coffee chain together with the first survey mailout.

Interventions

The intervention was a $10 Tim Hortons gift card given to half of the physicians who were randomly allocated to receive the incentive.

Results

265 (57.0%) physicians completed the survey. The response rate was significantly higher in the group allocated to receive the incentive (62.7% vs 51.3% in the control group; p=0.01).

Conclusions

Our results indicate that an unconditional incentive in the form of a coffee gift card can substantially improve physician response rates. Future research can look at the effect of varying amounts of cash on the gift cards on response rates.

Keywords: EPIDEMIOLOGY, GERIATRIC MEDICINE, QUALITATIVE RESEARCH

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Survey conducted using rigorous methodological approaches known to increase survey response rates such as modified Dillman techniques, key informant and cognitive interviews, pilot testing and a special contact.

Random unconditional distribution of incentives to half of the physicians.

High response rate.

Inability to check the effect of unconditional incentives within physician specialties.

We only studied the effect of a $10 coffee card.

Introduction

Postal surveys are an important research tool to ascertain physicians’ attitudes, knowledge, and practice patterns on different topics, but are recognised as a group from which it is often difficult to obtain high response rates.1 There are a number of reasons why physicians do not respond to surveys including lack of time, low perceived importance of study, an increased volume of surveys they are asked to respond to and concerns with confidentiality.2 However, to promote validity and generalisability of survey results, a high response rate must be achieved.3 A well-known method of improving survey design and increasing response rates is the Dillman's Tailored Design technique that is founded on social exchange theory.4 Social exchange theory indicates that an individual will exchange knowledge or expertise with others when he or she thinks that the reward for the exchange is equal to or greater than the cost, and trusts or expects that the rewards will outweigh the costs in the long run.4 Such strategies fall under two categories that one can use to improve response rates: incentive-based and design-based.2 Some design-based approaches include a personalisation of contacts,5 6 high interest factor,5 a shorter questionnaire6 and follow-up contacts.6–8 Research has shown that monetary incentives,9–14 as well as incentives in the form of a lottery ticket15 16 can increase response rates of physician surveys substantially. Information from the literature shows that incentives improve response rates but it is not clear how a gift card and its value can help improve response rates of physician surveys. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effect of unconditional incentives in the form of a coffee card on response rates.

Methods

Study design and participants

This study was a national self-administered postal survey of Canadian geriatricians, emergency physicians and family physicians. These physician groups were surveyed due to their involvement and treatment of elderly patients with minor injuries (ie, lacerations, contusions, non-operative fractures, etc). To be eligible for the study, the physicians must have been seeing elderly patients 65 years and older.

This was an a priori substudy to assess the effect of unconditional incentives, in the form of a $10 coffee card, on response rates of physician surveys. The study was conducted from April 2012 through November 2012. The primary objective of the survey was to determine physician requirements with respect to the minimally important change and the required sensitivity for clinical decision rules to predict functional decline 6 months after sustaining a minor trauma.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome was the physician response rate.

Questionnaire development

The survey design was informed by Dillman's Tailored Design method.17 In summary, the survey was developed in three stages: (1) key informant, in-person interviews (presurvey), (2) cognitive interviews (draft survey) and (3) pilot-testing (final draft survey) using rigorous methodological approaches including a well-designed and worded questionnaire, inclusion of a tangible token of appreciation provided in advance, personalised prenotification and cover letters, indication of a legitimate authority source, enhanced questionnaire arrangements and visual appeal.

The final questionnaire consisted of 13 questions, broken down into five sections and printed on two single-sided pages. Prenotification letters, English questionnaires and cover letters were translated into French by a medical translator and administered to those physicians who had indicated French as their language of correspondence in the Canadian Medical Directory. The questionnaire consisted of an eligibility question (one item), demographic and practice settings (seven items), assessment and measurement of functional decline (three items), relevance of ADL/IADL items to functional decline (one item), and required sensitivity for the clinical decision tool (one item).

Substantial effort, including design techniques, key informant interviews, cognitive interviews and pilot-testing was put into the survey design to ensure the survey questionnaire was relevant, clear and concise. The prenotification letters as well as the cover letters were all hand signed. The survey was personalised for each physician so that the physician's name, area of expertise and affiliation were printed on the cover letter.

Sample selection

A stratified random sample of 534 physicians (178 emergency physicians, 178 geriatricians and 178 family physicians) was selected, using computer-generated random numbers, from the Canadian Medical Directory. Of the 534 physicians, 101 (23 emergency physicians, 36 geriatricians and 42 family physicians) were mailed French-translated surveys.

Half of the physicians within each physician group were subsequently randomly allocated by computer to either receive a monetary incentive or be a control. Allocation concealment was achieved by this process.

Intervention

Physicians allocated to the incentive received a $10 Tim Horton's coffee card (a large national coffee chain) with the first survey. The cover letter indicated that this card was an incentive in recognition of their time. All other aspects of the prenotification, cover letters and survey instrument were identical to those in the control group. Respondents were blind to the intervention and so would not be aware that others may have received a different or no incentive.

Survey administration

The survey administration was informed by Dillman's Tailored Design method.17 We pretested the survey using 16 local physicians, from the randomly selected 534 physicians, to determine if there were any shortcomings with the survey process in terms of mail delivery and management of the surveys as well as ensuring the questionnaire was accurate in terms of sentence structure and format of the input fields. After we were satisfied with the survey process and questionnaire, we mailed the remaining 518 English and French surveys. The survey package consisted of a cover letter, a questionnaire, and a prepaid business reply mail envelope. A week after the prenotification letter, we mailed the first survey questionnaire, along with the coffee card, if applicable. A reminder with a questionnaire was systematically mailed every third week. Questionnaires were tracked using a unique number to avoid resending a questionnaire to the physicians that responded or those that had moved from the address we had on file. A final reminder survey was mailed using express courier service (Xpresspost). Compared to the regular mail, the Xpresspost is delivered nationally within two business days in a specialised envelope with dimensions of 15.2 cm by 26.0 cm, with the wording ‘Xpresspost’ plus the ability to track and confirm the delivery of the mail. In contrast, the regular mail is a plain envelope with dimensions 10.5 cm by 24.1 cm that is delivered within four business days with no tracking and no confirmation of delivery.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarise physician responses. χ2 Tests were conducted to compare characteristics of respondents and non-respondents and to explore the risk of non-response bias. χ2 Tests were also conducted to determine whether the response rates of the physicians who received the incentives were significantly higher than those who did not receive the incentives for the overall and within the subgroups. Line graphs were generated to present the response rates over time with each survey mailing. Two-sided significance tests were set at an α level of 0.05. Two demographic variables (language of correspondence and geographic region: Western Canada, Ontario, Quebec, Eastern Canada) were used to examine the possibility of non-response bias.

The sample size of 534 was determined to support the primary objective of the main study on determining the required sensitivity for a clinical decision rule. It was determined to yield a two-sided 95% CI around the mean estimated sensitivity with a maximum width of 4 for each specialty, accounting for the finite population correction factor and an anticipated response rate of 55%.

Data were analysed using SAS V.9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA).

Results

Respondents

Demographic characteristics of the respondents are presented in table 1. A slightly higher proportion (55.1%) of respondents was man, reflecting the higher prevalence of men in the survey population as per the Canadian Medical Directory; 76.5% of the physicians had been in practice for 10 or more years.

Table 1.

Respondent demographics

| Characteristic | Number (%) of respondents (N=265) |

|---|---|

| Specialty | |

| Geriatricians | 117 (44.2) |

| Family physicians | 67 (25.3) |

| Emergency physicians | 81 (30.6) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 146 (55.1) |

| Female | 119 (44.9) |

| Age | |

| <35 | 20 (7.5) |

| 35–44 | 88 (33.2) |

| 45–54 | 76 (28.7) |

| ≥55 | 78 (29.4) |

| Missing | 3 (1.1) |

| Years in practice | |

| <10 | 58 (21.9) |

| 10–19 | 95 (35.8) |

| ≥20 | 109 (41.1) |

| Missing | 3 (1.1) |

| Years of residency training | |

| <3 | 66 (24.9) |

| 3–5 | 137 (51.7) |

| >5–9 | 51 (19.2) |

| ≥10 | 4 (1.5) |

| Missing | 7 (2.6) |

| Number of patients seen/week | |

| ≤28 | 67 (25.3) |

| 29–60 | 71 (26.8) |

| 61–100 | 65 (24.5) |

| >100 | 57 (21.5) |

| Missing | 5 (1.9) |

| Number of elderly patients seen/week | |

| ≤20 | 79 (29.8) |

| 21–30 | 59 (22.3) |

| 31–50 | 69 (26.0) |

| >50 | 46 (17.4) |

| Missing | 12 (4.5) |

Two demographic variables (language of correspondence and geographic region: Western Canada, Ontario, Quebec, Eastern Canada) were used to examine the possibility of non-response bias. χ2 Analyses showed no significant differences in response rates among the English and French-speaking physicians (p value: 0.59; table 2). Similarly, there was no indication of a significant difference in response rates when we compared the regions (p value: 0.29). These are minimal tests for non-response bias that we were able to conduct.

Table 2.

χ2 tests of non-response bias

| Characteristic | Respondents % (n) | Non-respondents % (n) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Language of the questionnaire | 0.59 | ||

| English | 81.5 (216) | 79.5 (159) | |

| French | 18.5 (49) | 20.5 (41) | |

| Region | 0.29 | ||

| Western Canada* | 28.3 (75) | 33.5 (67) | |

| Ontario | 41.5 (110) | 38.0 (76) | |

| Quebec | 21.5 (57) | 23.5 (47) | |

| Eastern Canada† | 8.7 (23) | 5.0 (10) |

*British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Yukon Territory.

†New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Newfoundland.

Response rate

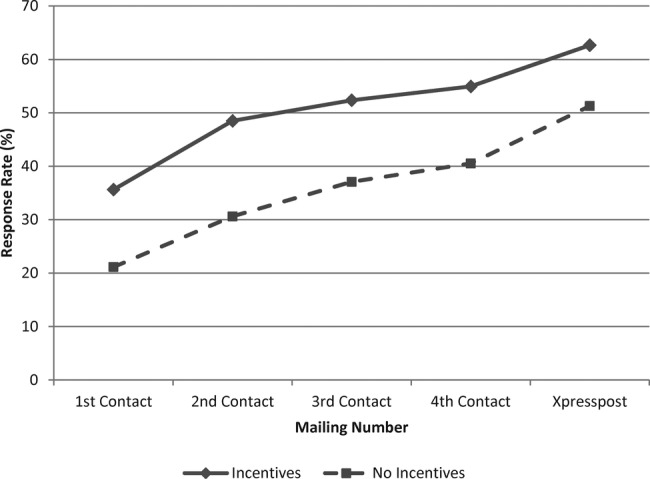

Of the 534 physicians surveyed, 27 were not reachable because they had moved and 42 were ineligible as they were no longer practising or were not seeing elderly patients. Of the 465 eligible physicians, 265 completed and returned the survey (including the 12 of the 16 physicians from the local pilot survey) resulting in an overall response rate of 57% (95% CI 52.4% to 61.5%). In general the conditional response rates (ie, response rates among remaining non-responders), declined with each contact except for the courier service which had an increased conditional response rate, figure 1.

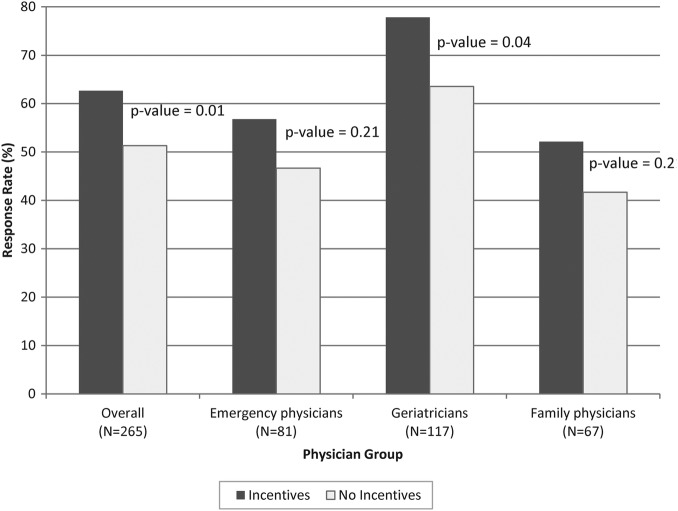

Figure 1.

Response rates for incentive vs no-incentive arms by physician subgroups.

The response rate of the physicians who received a $10 coffee gift card (62.7%; 95% CI 56.1% to 68.9%) was significantly higher than the response rate of the physicians who did not receive the coffee card (51.3%; 95% CI 44.7% to 57.9%), absolute difference 11.4%, p=0.01; figure 2). When looking at the subgroups of individual physician groups, the response rate of the geriatricians who received an incentive (77.8%; 95% CI 67.2% to 86.3%) were significantly higher (p=0.04) than the response rate of the geriatricians who did not receive an incentive (63.5%; 95% CI 52.4% to 73.7%). The response rates for emergency physicians and family physicians with incentives (56.8% (95% CI 45.3% to 67.8%) and 52.1% (95% CI 39.9% to 64.1%), respectively) were higher than for those who did not receive incentives (46.7% (95% CI 35.1% to 58.6%) and 41.7% (95% CI 30.2% to 53.9%), respectively) but differences were not statistically significant (p=0.21 and p=0.21, respectively).

Figure 2.

Cumulative response rate with and without incentives.

Discussion

We found that physicians who received a coffee card had a significantly higher response rate than physicians who did not receive this incentive. All three physician groups demonstrated similar increased response rates with incentive use.

These results are consistent with the work of other investigators who have reported increased response rates with incentives.2 11 12 14 Unlike some of the studies, this study provided unconditional incentives that were randomly given to a random sample of physicians. While other researchers looked at the effect of incentives on a select group of physicians we studied the effect of incentives on different specialties that had different interest levels for the study. Other investigators have shown that unconditional incentives generate higher response rates than conditional and delayed incentives.13 This study looked at coffee gift cards instead of cash or cheque incentives. Our results show that monetary incentives, even in a form of a coffee gift card, help increase response rates significantly. One of the main reasons why such a strategy of an unconditional incentive improves response rates relates to trust in the context of social exchange theory. We build trust with the physicians by providing an incentive with the first survey. Another reason for obtaining higher response rates with incentives is that the physicians feel obliged to respond after they receive the incentive. Although larger incentives are more effective in increasing response rates our results suggest that a $10 coffee card, that could buy about seven medium-sized cups of coffee at the time of the study, is sufficient to help increase the response rates of physicians significantly.18

This was an a-priori sub-study to assess the effect of unconditional incentives on response rates, our primary outcome was to define functional decline and determine the required sensitivity for a clinical decision tool to identify elderly patients at high risk of functional decline. Although the incentives help increase response rates it is possible that there is an interaction effect between the incentives and relevance of the study as with our study that was very relevant to the geriatricians. Further research is needed to study the effect of a combination of methods on response rates.

Study limitations

There are a few limitations with this study. There is a possibility of not having all the physicians across the country included in the directory which could lead to a biased sample. However, these limitations are minimal as the Medical Directory is known to be very accurate.

A limitation with this study is a low power to test for the effect of unconditional incentives within physician specialties. We also did not test other types of incentives or the effect of alternative amounts of incentives. This will need to be assessed based on the study being conducted, where scientific rigour with an improved response rate and less chance of non-response error needs to be balanced with the value of the study question and the need for a scientifically reliable answer.

Future research

Future studies could expand on this study by testing different amounts of coffee card values and their association with response rates. Further research can look into the effect of special contacts with and without incentives as there could be an interaction effect when using a combination of a special contact with an incentive. The effect of such a special contact could be studied further by looking at its effect on different physician specialties since not all physicians have the same work-office work environment. Future studies should also assess the use of unconditional incentives for electronic surveys.

Conclusion

We found that incentives, in the form of a $10 coffee gift card, significantly improved physician response rates. We therefore encourage investigators conducting physician surveys to routinely include incentives in order to improve response rates and lessen the risk of non-response bias.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the physicians at The Ottawa Hospital who allowed us to interview them and for their feedback. Thanks to Angela Marcantonio, Cathy Clement and Jane Sutherland for their assistance throughout the project. The authors would also like to thank all the physicians who took the time to complete and return their surveys.

Footnotes

Contributors: KA was involved in the study design, survey mailing, data analysis, interpretation of data and preparation of manuscript. JJP, JB, MT were involved in the study design, interpretation of data, preparation of manuscript. MÉ was involved in the study design, funding, preparation of manuscript. LW, M-JS, JSL were involved in the study design, preparation of manuscript.

Funding: Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) for the Canadian Emergency department Team Initiative (CETI) in mobility in aging (Grant # AAM-108750); the University of Ottawa Department of Emergency Medicine.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Researchers coordinating this study were located at the Ottawa Hospital Research Institute in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. The study was provided expedited review and approval by the Ottawa Health Science Network Research Ethics Board.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Thorpe C, Ryan B, McLean SL et al. How to obtain excellent response rates when surveying physicians. Fam Pract 2009;26:65–8. 10.1093/fampra/cmn097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.VanGeest JB, Johnson TP, Welch VL. Methodologies for improving response rates in surveys of physicians: a systematic review. Eval Health Prof 2007;30:303–21. 10.1177/0163278707307899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hocking JS, Lim MS, Read T et al. Postal surveys of physicians gave superior response rates over telephone interviews in a randomized trial. J Clin Epidemiol 2006;59:521–4. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dillman DA. Mail and internet surveys: the tailored design method. Wiley, 2nd edn 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaner EF, Haighton CA, McAvoy BR. ‘So much post, so busy with practice—so, no time!’: a telephone survey of general practitioners’ reasons for not participating in postal questionnaire surveys. Br J Gen Pract 1998;48:1067–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakash RA, Hutton JL, Jorstad-Stein EC et al. Maximising response to postal questionnaires—a systematic review of randomised trials in health research. BMC Med Res Methodol 2006;6:5 10.1186/1471-2288-6-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Edwards P, Roberts I, Clarke M et al. Increasing response rates to postal questionnaires: systematic review. BMJ 2002;324:1183 10.1136/bmj.324.7347.1183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burns KE, Duffett M, Kho ME et al. A guide for the design and conduct of self-administered surveys of clinicians. CMAJ 2008;179:245–52. 10.1503/cmaj.080372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donaldson GW, Moinpour CM, Bush NE et al. Physician participation in research surveys. A randomized study of inducements to return mailed research questionnaires. Eval Health Prof 1999;22:427–41. 10.1177/01632789922034392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deehan A, Templeton L, Taylor C et al. The effect of cash and other financial inducements on the response rate of general practitioners in a national postal study. Br J Gen Pract 1997;47:87–90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kellerman SE, Herold J. Physician response to surveys. A review of the literature. Am J Prev Med 2001;20:61–7. 10.1016/S0749-3797(00)00258-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keating NL, Zaslavsky AM, Goldstein J et al. Randomized trial of $20 versus $50 incentives to increase physician survey response rates. Med Care 2008;46:878–81. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318178eb1d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosoff PM, Werner C, Clipp EC et al. Response rates to a mailed survey targeting childhood cancer survivors: a comparison of conditional versus unconditional incentives. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2005;14:1330–2. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edwards PJ, Roberts I, Clarke MJ et al. Methods to increase response to postal and electronic questionnaires. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009;(3):MR000008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baron G, De WP, Milord F. Cost-effectiveness of a lottery for increasing physicians’ responses to a mail survey. Eval Health Prof 2001;24:47–52. 10.1177/01632780122034777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leung GM, Ho LM, Chan MF et al. The effects of cash and lottery incentives on mailed surveys to physicians: a randomized trial. J Clin Epidemiol 2002;55:801–7. 10.1016/S0895-4356(02)00442-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sutton M, Grimmer-Somers K, Jeffries L. Screening tools to identify hospitalised elderly patients at risk of functional decline: a systematic review. Int J Clin Pract 2008;62:1900–9. 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2008.01930.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pit SW, Vo T, Pyakurel S. The effectiveness of recruitment strategies on general practitioner's survey response rates—a systematic review. BMC Med Res Methodol 2014;14:76 10.1186/1471-2288-14-76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]