Abstract

Peroxiredoxins (Prxs) catalyze the reduction of peroxides, a process of key relevance in a variety of cellular processes. The first step in the catalytic cycle of all Prxs is the oxidation of a cysteine residue to sulfenic acid, which occurs 103-107 times faster than in free cysteine. We present an experimental kinetics and hybrid QM/MM investigation to explore the reaction of Prxs with H2O2 using alkyl hydroperoxide reductase E from Mycobacterium tuberculosis as a Prx model. We report for the first time the reaction thermodynamical activation parameters of H2O2 reduction by a Prx, which show that the protein lowers significantly the activation enthalpy, with an unfavourable entropic effect, compared to the uncatalyzed reaction. The QM/MM simulations show that the remarkable catalytic effects responsible for the fast H2O2 reduction in Prxs are mainly due to an active-site arrangement, which establishes a complex hydrogen bond network activating both reactive species.

Peroxiredoxins (Prxs, EC 1.11.1.15) are ubiquitous broad spectrum peroxidases that catalyze the reduction of peroxides such as hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), organic hydroperoxides and peroxynitrite, via the oxidation of a cysteine (Cys) residue, the peroxidatic Cys (CysP) which occurs several orders of magnitude faster than in the case of free Cys. Although this reaction has been extensively studied in different Prxs, the molecular basis underlying the catalysis of the peroxide reduction step accomplished by these enzymes, remains poorly understood.

Prxs have been demonstrated to play protective roles against the development of different diseases in which oxidative stress play a pathogenic role.1-3 They have high expression levels (up to 1% of cellular proteins)4 and very fast catalytic rates in the order of ~105-108 M−1s−1.5,6 Competitive kinetics analysis predicts that Prxs are responsible for the reduction of most of mitochondrial and cytoplasmic H2O2 in eukaryotic cells.4,7 Besides their role in antioxidant defences, some Prxs have been identified as key participants in the regulation of redox signalling pathways.8-10 The catalytic cycle of Prxs involves the two-electron oxidation of CysP, the formation of a disulfide bond with a second Cys residue or low molecular weight thiol, and the posterior recycling step through thiol/disulfide exchange reactions.11 Prxs can be classified into six subfamilies by sequence analysis (AhpC-Prx1, Prx6, Prx5, Tpx, BCP-PrxQ, AhpE; http://csb.wfu.edu/prex.test/prxInfo.php, see reference 12 for a detailed description); or in three classes by a mechanistic criteria based on the requirement of a second resolving Cys.10 Importantly, the active site of Prxs is highly conserved, and they all share a common first step of the catalytic cycle in which the thiolate in CysP is oxidized to sulfenic acid:

| (eq. 1) |

This is a rapid and chemically interesting event, which consists in a bimolecular nucleophilic substitution on the reactive oxygen atom of the peroxide. The key issue in the molecular basis of the catalytic ability of peroxiredoxins is to understand how the active site microenvironment of these enzymes can accelerate by factors of ~103-107 H2O2 reduction compared to the uncatalyzed reaction, i.e. that of free Cys in aqueous solution. Fast reactivity was firstly attributed to the low CysP pKa, assuring thiolate availability at physiological pH values, mostly due to a pair of very conserved charge-stabilizers arginine (Arg) and threonine (Thr) residues in the active-site. However, this phenomenon can only account for a ten- fold acceleration of H2O2 reduction velocity rates at pH 7.4.13 Very recently, by means of a thorough structural analysis of members of different subfamilies of Prxs, a complete overview of the active-site structure and its interactions with the peroxide substrate has been accomplished.14 Moreover, the authors proposed a transition state (ts) model, in which a complex hydrogen bond network is assumed to be responsible for ts stabilization. Summing up, the above presented evidence point out to the fact that all Prxs are expected to behave according to the same general oxidative mechanism.

In this work we performed a thorough investigation of the key oxidation reaction mechanism of Prxs using Mycobacterium tuberculosis AhpE (MtAhpE) as a model. MtAhpE is the representative of AhpE, a novel subgroup of the Prxs family. It is a 1-Cys Prx and it is mostly an A-type dimer in solution.15 Structural analysis shows the resemblance, not only at the sequence level but from a structural viewpoint, of this Prx active-site with other proteins of the family.15 We have previously conducted a complete kinetic characterization,16,17 finding that MtAhpE reduces H2O2 with a rate constant equal to 8.2 × 104 M−1s−1 at pH 7.4 and 25°C. The reason of our choice is that MtAhpE shows changes in intrinsic fluorescence intensity that occur during protein oxidation facilitating single-turnover kinetic determinations which are not possible in most other cases, and for which indirect approaches are required.18 Moreover, H2O2 reduction by this enzyme is much faster than by free Cys, but still, it is not so fast as to preclude very precise kinetic experiments using stopped-flow methodologies. This fact allows us to report for the first time activation thermodynamic parameters determinations for Prxs. In addition, we also used a theoretical approach in order to identify and characterize the molecular basis that explains the catalytic ability of these enzymes. Specifically, we compute the free energy profile for the reaction by means of state of the art quantum mechanics (at DFT-PBE level)/molecular mechanics (QM/MM)19 umbrella sampling simulations (see Supplementary Information). This simulation scheme, which has been previously applied with success in similar processes,20,21 allows us to compute free energies profiles as well as the evolution of the electronic properties along the reaction coordinate, within a realistic representation of the enzyme microenvironment.

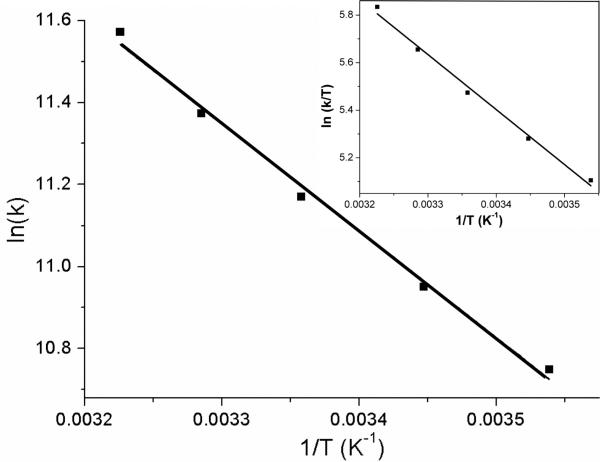

Rate constant temperature-dependence of the reduction of H2O2 by MtAhpE at pH 7.4 is presented in Figure 1 (to observe kobs (s−1) as a function of H2O2 concentration, see supplementary Figure S1). As described previously,16 the enzyme catalyzes the reaction by a factor of ~6 × 104 in terms of apparent rate constants at pH 7.4, and ~5 × 103 in terms of pH-independent rate constants, compared to the reaction with free Cys at 25°C.22 Remarkably, the analysis of the thermodynamic activation parameters compared to those obtained for free Cys22 (Table 1), illustrates that the ΔG# decrease is explained by means of two opposing terms; while this Prx is capable to greatly diminish ΔH#, which is almost four times smaller in the enzyme than in solution, the unfavourable entropic contribution (-TΔS#=5.7±0.7 kcal mol−1), signifies that the -TΔS# term represents more than 50% of the total ΔG# at 25°C. This may indicate that Prxs active site are designed to significantly improve the interaction with the reaction's ts, shaping a very ordered ts (as will be described below), resulting in a net decrease of ΔG#.

Figure 1.

Rate constant temperature dependence of the reduction of H2O2 by MtAhpE at pH 7.4. Arrhenius and Eyring's analysis (inset) of rate constants determined at T=10, 16.5, 25, 31.5 and 37°C are shown. Figure corresponds to one independent experiment that was repeated three times with almost identical results.

Table 1.

Kinetic and thermodynamics activation parameters for the reduction of H2O2 by free Cys and MtAhpE. Standard deviations in parenthesis when available.

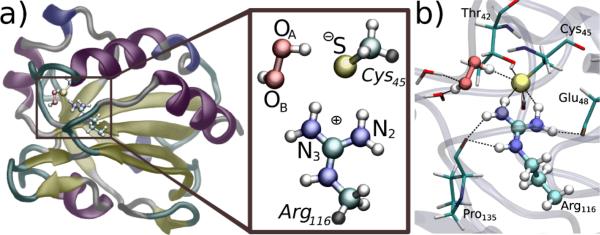

Previous to the exploration of the reaction's free energy profile, a survey of the structure and dynamical behaviour of the MtAhpE dimer was performed by means of classical molecular dynamics simulations (MD), with the crystal structure of the reduced enzyme as starting point (PDBid: 1XXU)15 and considering the unprotonated form of CysP (Cys45), since its pKa has been reported as 5.2.16 As general to all Prxs, CysP is positioned at the N-terminal helix α2 at the bottom of the active-site pocket and its thiolate negative charge is mainly stabilized by conserved Thr and Arg residues (Thr42 and Arg116 in MtAhpE). Particularly, the Arg116 is strongly positioned towards CysP via the interaction with other two residues: the mostly conserved Glu48 and the backbone of Pro135.

Although CysP lies at the base of the active site pocket, the thiolate moiety exhibits significant solvation, as it is not a hydrophobic active-site. Moreover, in the presence of H2O2 in the Michaelis complex (reactant state, rs), 2-3 water molecules are also present, but the thiolate group becomes less solvated (see supplementary information Figure S2). The rs is characterized by a strong H-bond type interaction between S and OA, with an (S-OA-OB) angle of ~90° (See Figure 2 and supplementary information Table S1). Besides the interaction between the sulfur atom of CysP and H2O2, the peroxide moiety is located in this particular position inside the active-site, due to two weak H-bonds with the amide-N atom of CysP and with N3 of Arg116. A comparision of this Michaelis complex with the one obtained by X-ray crystallography in the archeal Prx ApTPx (the only experimental determined structure of a Prx with H2O2 in its active-site)23 shows some subtle differences; although the peroxide is maintained by very similar interactions in both cases, ApTPx-H2O2 complex presents a slightly longer S-OA distance and a quasi-linear S-OA-OB angle.

Figure 2.

a) Representation of the MtAhpE (only one monomer is shown) with H2O2 in the active-site (rs), along with a schematic view of the quantum subsystem, i.e. Cys45 and Arg116 sidechains and the H2O2 moiety. Atoms names as referred in the text, and colored according to their type: white, hydrogen; cyan, carbon; red, oxygen; blue, nitrogen; yellow, sulfur. Link atoms are shown in grey. b) Representative structure of the rs. H2O2, S atom from Cys45 and Arg116 sidechain are represented as balls, while sidechains of Thr42, Glu48 and Pro135 and water molecules are represented by sticks.

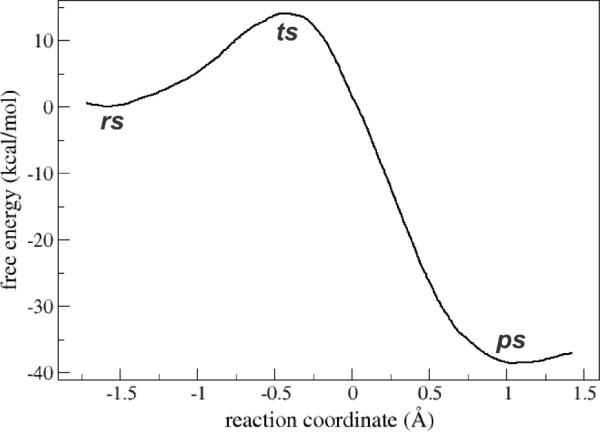

Umbrella sampling QM/MM simulations were started from the classically modelled rs (see Figure 2), and the reaction was considered as a substitution displacement, choosing as reaction coordinate the difference between the OA-OB and the S-OA distances. The obtained free energy profile is depicted in Figure 3. The reaction is clearly exergonic, with a change in the free reaction energy of about -38 kcal mol−1, also in agreement with previously reported information for the uncatalyzed reaction.20 Even though it shows a ΔG# of ~14 kcal mol−1, resulting in a modest overestimation in comparison with the experimental determined one (see Table 1), it represent a ~4 kcal mol−1 decrease compared to our previous study of a model thiolate in aqueous solution,20 which is consistent with the experimental determined ΔΔG#=5.4 kcal mol−1 and with the ~5000 fold increase in reactivity observed.

Figure 3.

Free energy profile of the reduction of H2O2 by MtAhpE obtained by QM/MM umbrella sampling. The reaction coordinate was defined as the difference between the OA-OB distance and the S-OA distance, and was sampled from -1.7 to 1.4 Å.

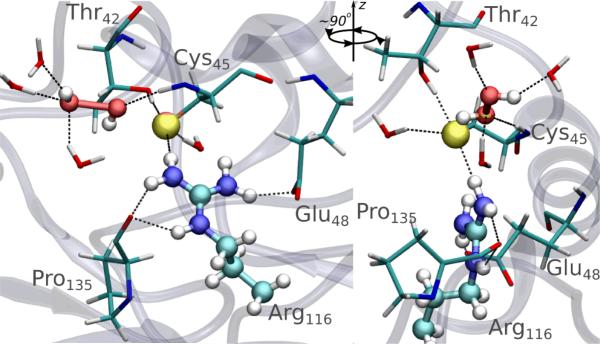

This simulation scheme allows getting a microscopic insight into the reaction mechanism, as well as a detailed description of the system properties at different stages of the process (see the 3D animation available in supporting information for illustration). As proposed by Hall and co-workers,14 the reaction consists, at least at first stages, of a simple bimolecular SN2 substitution, with S as the nucleophile and OA as the electrophile. The set of molecular factors that determines catalysis can be integrated within the ts stabilization framework,24 so a detailed description of ts behaviour is of great significance. Firstly, as expected for this kind of substitutions, the ts is almost “linear” with a (S-OA-OB) angle of ~160°, where the peroxidatic bond is practically broken and the S-OA bond is in formation process (see Figure 4 and supplementary information Table S1). This approach and alignment of the peroxide's oxygen atoms towards the thiolate, is guided by a great improvement in the interactions between H2O2 and the enzyme that were described for the rs. OA is markedly positioned by a strong H-bond with the amide-N atom of CysP and leaded by the interaction with Arg116. This Arg116 along with Thr42, retain the S atom in the reactive position. OB points outside the pocket and interacts with water molecules. Indeed, the active-site residues present a complex H-bond intra- and inter-molecular network (Figure 4). In this context, Nagy et al reported that the above mentioned Arg residue plays a key role in activating the peroxide that also involves hydrogen bonding to a second Arg conserved in some Prx families (Prx1, Prx6 and AhpE).25 However, the role of the latter is under debate.14,26 Our simulations indicate that if there is a role of this second Arg it is indirect by assisting in the building of the active-site architecture. The strong interactions with Arg116 and Thr42 residues are the main responsible for the ts stabilization and the concomitantly significant reduction in the ΔH#, which in turn results in a decrease in ΔG# in spite of the unfavourable entropic contribution.

Figure 4.

Two different views of a typical snapshot corresponding to the ts. H2O2, S atom from Cys45 and Arg116 sidechain are represented as balls, while sidechains of Thr42, Glu48 and Pro135 and water molecules are represented by sticks. Atoms are coloured according to their type: white, hydrogen; cyan, carbon; red, oxygen; blue, nitrogen; yellow, sulfur. Important hydrogen bonds are indicated by dashed black lines.

As previously described,20 the reaction is driven by the tendency of the slightly charged peroxide's oxygen atom to become even more negative, therefore the system must experience a significant charge redistribution (see Mulliken's population over relevant atoms upon reaction in supplementary information Figure S4). At the same time as the S atom looses negative charge, its charge is been acquired by both OA and OB atoms. The set of interactions described above, guides this process, allowing charge redistribution to take place at a lower energy cost compared to the reaction in aqueous solution. Specifically, our results confirm the key role of Arg116. In the reactant state both N2 and N3 Arg atoms stabilize the thiolate moiety of the reactive Cys. In the transition state, the incipient negative charge on sulfenic OA atom is partially stabilized by Arg116 N3 that then establishes a strong interaction in the product state (Table S1). This shows that the plasticity of Arg116 motions is probably the key issue in the catalysis.

After the system has reached the ts, a proton transfer from OA to OB occurs, as previously reported for low molecular weight model thiolate oxidation by H2O2 (see supplementary information Table S1).20,27 Therefore, the reaction yields the oxidized CysP in the unprotonated form of sulfenic acid (CysPSO−) and a water molecule. The product state (ps) is characterized by important changes in the active-site microenvironment, Arg116 moves inside the pocket in order to maintain the contacts with both S and OA atom, the newly oxidized CysPSO− side chain loses its interaction with Thr42 and the negative charge concentrated in OA atom is now stabilized by Arg116 (so much that a proton can be considered as “shared” by this two moieties), the strong interaction with the amide-N atom and water molecules that fill the pocket (see supplementary information Table S1 and Figure S3).

In summary, our calculations support the idea of a bimolecular nucleophilic substitution SN2 type mechanism, with an internal proton transfer. No evidence of acid-base catalysis was observed. Thus, the extraordinary catalytic ability of these enzymes towards peroxide reduction is not related with a change in the overall mechanism in comparison with the same reaction in aqueous solution. The power of Prxs lies on their capability to stabilize the ts over rs due to an active-site design, which is capable to lay out a complex H-bond network activating both reactive species, i.e. CysP and the peroxide substrate. The activation parameters experimentally determined are in agreement with this kind of ts stabilization.

The precise knowledge of the catalytic mechanisms of Prxs provides the basis to understand their prominent roles in antioxidant defenses and redox signaling pathways.1-3 Moreover, the interactions between specific amino acids and the peroxide substrate at the rs and ts described herein will be helpful for the design of potential inhibitors of these enzymes.28 This could provide tools for the treatment of infectious diseases as well as specific forms of cancer where peroxides play a cytotoxic role,29 or to modulate particular signaling processes.30 However, the design of inhibitors for specific Prxs will be challenging, due to the very conserved peroxidatic active site structure in the different members of the family.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

This work was partially supported by the Universidad de Buenos Aires, CONICET, Centro de Biología Estructural Mercosur (CeBEM). MT and RR acknowledge the financial support of the Agencia Nacional de Investigación e Innovación (FCE_2011_1_5706, ANII, Uruguay) and Comisión Sectorial de Investigación Científica (CSIC), Universidad de la República and National Institutes of Health (R01 AI095173), respectively.

Footnotes

† Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: Experimental procedures, computer simulations details, additional results and 3D animation specifications included in the supporting information. See DOI: 10.1039/b000000x/

Notes and references

- 1.Bell KF, Hardingham GE. Antioxid. Redox Signalling. 2011;14:1467. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eismann T, Huber N, Shin T, Kuboki S, Galloway E, Wyder M, Edwards MJ, Greis KD, Shertzer HG, Fisher AB, Lentsch AB. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2009;296:266. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.90583.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hu X, Weng Z, Chu CT, Zhang L, Cao G, Gao Y, Signore A, Zhu J, Hastings T, Greenamyre JT. J. Chen. Neurosci. 2011;31:247. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4589-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Winterbourn CC. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2008;4:278. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poole LB. In: Peroxiredoxin Systems. Flohé L, Harris JR, editors. New York: Springer. 2007. p. 61. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trujillo M, Ferrer-Sueta G, Thomson L, Flohe L, Radi R. Subcell. Biochem. 2007;44:83. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4020-6051-9_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cox A, Winterbourn CC, Hampton M. Biochem. J. 2010;425:313. doi: 10.1042/BJ20091541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Randall LM, Ferrer-Sueta G, Denicola A. Method. Enzymol. 2012;527:41. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-405882-8.00003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flohé L. Method. Enzymol. 2010;473:1. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(10)73001-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wood ZA, Poole LB, Karplus PA. Science. 2003;300:650. doi: 10.1126/science.1080405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hall A, Nelson K, Poole LB, Karplus PA. Antioxid. Redox Signalling. 2011;15:795. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Soito L, Williamson C, Knutson ST, Fetrow JS, Poole LB, Nelson KJ. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D332. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferrer-Sueta G, Manta B, Botti H, Radi R, Trujillo M, Denicola A. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2011;24:434. doi: 10.1021/tx100413v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hall A, Parsonage D, Poole LB, Karplus PA. J. Mol. Biol. 2010;402:194. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li S, Peterson NA, Kim MY, Kim CY, Hung LW, Yu M, Lekin T, Segelke BW, Lott JS, Baker EN. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;346:1035. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hugo M, Turell L, Manta B, Botti H, Monteiro G, Netto LE, Alvarez B, Radi R, Trujillo M. Biochemistry. 2009;48:9416. doi: 10.1021/bi901221s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reyes AM, Hugo M, Trostchansky A, Capece L, Radi R, Trujillo M. Free Rad. Biol. Med. 2011;51:464. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ogusucu R, Rettori D, Munhoz DC, Netto LE, Augusto O. Free Rad. Biol. Med. 2007;42:326–334. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.10.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Senn HM, Thiel W. Angew. Chem. 2009;121:1220. doi: 10.1002/anie.200802019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zeida A, Babbush R, González Lebrero MC, Trujillo M, Radi R, Estrin DA. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2012;25:741. doi: 10.1021/tx200540z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zeida A, González Lebrero MC, Radi R, Trujillo M, Estrin DA. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2013;539:81. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2013.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luo D, Smith SW, Anderson BD. J. Pharm. Sci. 2005;94:304. doi: 10.1002/jps.20253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nakamura T, Kado Y, Yamaguchi T, Matsumura H, Ishikawa K, Inoue T, Biochem-Tokio J. 2010;147:109. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvp154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garcia-Viloca M, Gao J, Karplus M, Truhlar DG. Science. 2004;303:186. doi: 10.1126/science.1088172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nagy P, Karton A, Betz A, Peskin AV, Pace P, O'Reilly RJ, Hampton MB, Radom L, Winterbourn CC. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:18048. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.232355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tairum CA, Jr, de Oliveira MA, Horta BB, Zara FJ, Netto LE. J. Mol. Biol. 2012;424:28. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2012.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cardey B, Enescu MA. ChemPhysChem. 2005;6:1175. doi: 10.1002/cphc.200400568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lodola A, De Vivo M. Adv. Protein Chem. Struct. Biol. 2012;87:337. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-398312-1.00011-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lu W, Fu Z, Wang H, Feng J, Wei J. J. Guo. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2014;387:261. doi: 10.1007/s11010-013-1891-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Woo HA, Chae HZ, Hwang SC, Yang KS, Kang SW, Kim K, Rhee SG. Science. 2003;300:653. doi: 10.1126/science.1080273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.