Abstract

Background

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) and related risk factors are associated with Alzheimer’s disease (AD). This association is less well-defined in normal cognition (NC) or prodromal AD (mild cognitive impairment (MCI)).

Objective

Cross-sectionally and longitudinally relate a vascular risk index to cognitive outcomes among elders free of clinical dementia.

Methods

3117 MCI (74±8 years, 56% female) and 6603 NC participants (72±8 years, 68% female) were drawn from the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center. A composite measure of vascular risk was defined using the Framingham Stroke Risk Profile (FSRP) score (i.e., age, systolic blood pressure, anti-hypertensive medication, diabetes, cigarette smoking, CVD history, atrial fibrillation). Ordinary linear regressions and generalized linear mixed models related baseline FSRP to cross-sectional and longitudinal cognitive outcomes, separately for NC and MCI, adjusting for age, sex, race, education, and follow-up time (in longitudinal models).

Results

In NC participants, increasing FSRP was related to worse baseline global cognition, information processing speed, and sequencing abilities (p-values<0.0001) and a worse longitudinal trajectory on all cognitive measures (p-values<0.0001). In MCI, increasing FSRP correlated with worse longitudinal delayed memory (p=0.004). In secondary models using an age-excluded FSRP score, associations persisted in NC participants for global cognition, naming, information processing speed, and sequencing abilities.

Conclusions

An adverse vascular risk profile is associated with worse cognitive trajectory, especially global cognition, naming, and information processing speed, among NC elders. Future studies are needed to understand how effective management of CVD and related risk factors can modify cognitive decline to identify the ideal timeframe for primary prevention implementation.

Keywords: Blood pressure, diabetes mellitus, smoking, Framingham Stroke Risk Profile, stroke

Introduction

Established vascular risk factors, such as hypertension [1], diabetes mellitus [2], and cigarette smoking [3], are associated with increased risk for Alzheimer’s disease (AD). The mechanism by which poor vascular health relates to AD is likely multifactorial with possibilities including cerebral blood flow alterations [4], impaired clearance of neuropathological substrates across the blood-brain barrier [5], and neural vulnerability from vascular-related injury in both gray and white matter [6,7].

Vascular risk factors also relate to worse cognitive performance prior to the onset of clinical AD [8,9]. Among older adults free of clinical dementia and stroke, elevations in a common vascular risk index (i.e. the Framingham Stroke Risk Profile (FSRP)) [10] are cross-sectionally [10] and longitudinally [11] associated with worse executive function, verbal fluency, abstract reasoning, attention, and visuospatial episodic memory performance. In contrast, for verbal episodic memory performance, some studies have reported cross-sectional associations with FSRP [12,13], but a majority of longitudinal studies have failed to detect a significant association [8,11,14]. Such disparate findings highlight the need for additional work using more stringent longitudinal methods. For example, inconsistencies in the literature may be due to cohort differences in vascular risk profiles, as studies demonstrating no effect tend to come from younger cohorts at lower risk [9,11,14], while studies demonstrating an effect or mixed effect tend to have higher baseline age [13] or variability in FSRP [12]. Finally, a majority of studies are limited to individuals free of clinical dementia and stroke but fail to consider diagnostic variations within the cognitive aging spectrum prior to the onset of dementia (i.e., cognitively normal controls (NC) or individuals with mild cognitive impairment (MCI), a precursor to AD [15]). Collectively, existing findings have implicated FSRP in cognitive decline in NC but have not offered a comprehensive understanding on how such relations differ in older adults with MCI versus NC.

This study aims to reconcile discrepancies in the literature while expanding our current understanding of vascular health and cognitive performance among older adults by cross-sectionally and longitudinally analyzing a robust national dataset with over 9000 participants. We consider both cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses, we include participants representing two key phases of the cognitive aging spectrum (i.e., normal cognition and MCI), and we leverage an integrative vascular risk index rather than taking a more traditional “silo” approach that focuses on a single risk factor, such as blood pressure. We hypothesized that worse vascular risk would be associated with a decline in cognitive performance among both groups, particularly in domains known to be affected by microvascular disease (i.e., episodic memory, information processing speed, and executive function) [16–18]. In light of our prior work highlighting the incremental value of examining vascular health in a categorical manner versus just as a continuous variable [19], we considered vascular risk both as a continuous and a categorical predictor.

Methods

Participants

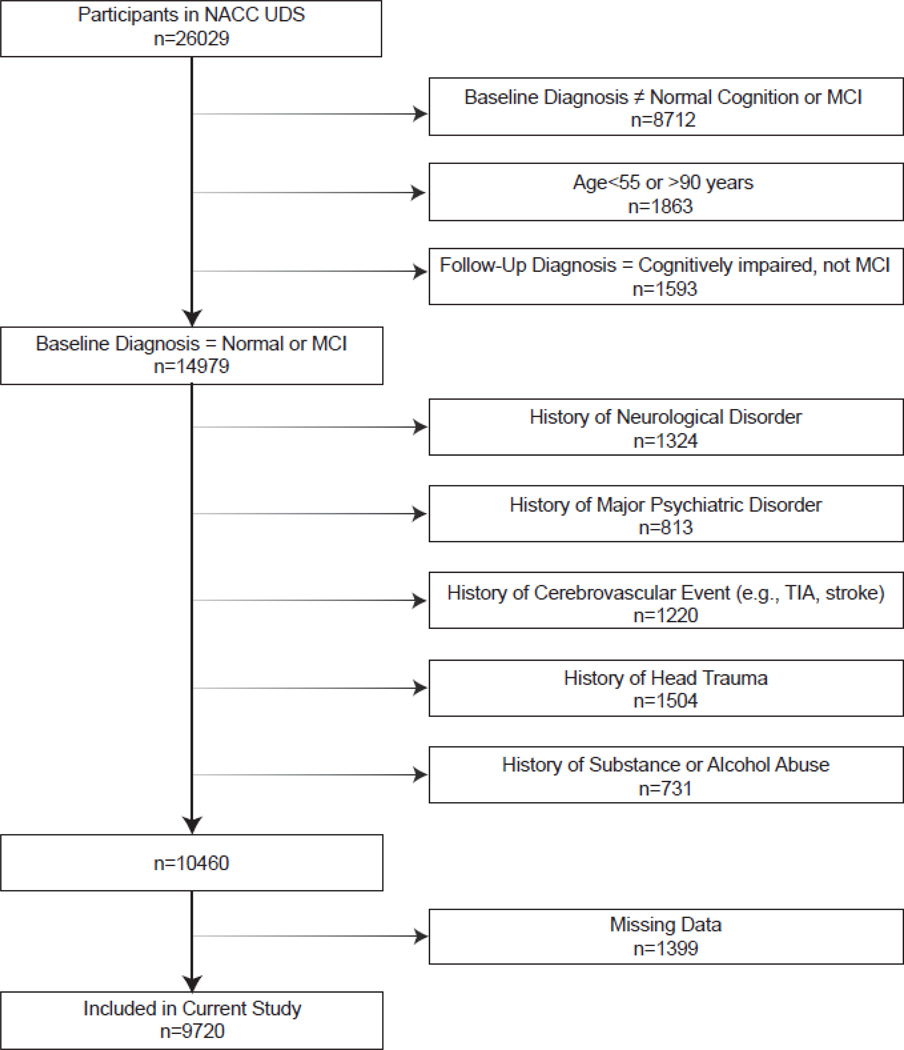

The National Alzheimer's Coordinating Center (NACC) maintains a database of participant information collected from 34 past and present National Institute on Aging-funded Alzheimer’s Disease Centers. In 2005, NACC implemented the Uniform Data Set (UDS), a standard data collection protocol, including clinical, medical history, neurological, and neuropsychological results [20]. Participants between 55 and 90 years of age evaluated between 9/01/2005 and 3/01/2014 with a diagnosis at first UDS visit of NC or MCI were included in the current study. Participant selection and exclusion details (n=9720) are provided in Figure 1. This study was approved by the local Institutional Review Board prior to data access or analysis.

Figure 1. Participant Inclusion & Exclusion Details.

The exclusion numbers are not mutually exclusive. Missing data includes baseline demographic variables (i.e., education, race), FSRP values, and outcomes. Within the missing data category (n=1399), the majority of individuals were excluded due to missing outcomes (n=1043).

Cognitive Diagnostic Classification

Cognitive diagnosis for each participant is based upon clinician judgment or a multi-disciplinary consensus team using information from the comprehensive UDS work-up, including:

NC is defined by Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) [21]=0 (no dementia), no deficits in activities of daily living that could be directly attributable to cognitive impairment, and no evidence of cognitive impairment defined as standard scores equal to or more than −1.5 standard deviations from age-adjusted normative mean [22].

MCI determinations are based upon Peterson et al. criteria [23] and defined as a CDR score 0.0 to 1.0 (reflecting mild severity of impairment), relatively spared activities of daily living, objective cognitive impairment in at least one cognitive domain (i.e., performances equal to or more than −1.5 standard deviations from the age-adjusted normative mean) or a significant decline over time on the neuropsychological evaluation, and absence of a dementing syndrome.

Framingham Stroke Risk Profile (FSRP)

To assess systemic vascular health, we calculated a FSRP at baseline [12,24], which assigns points for age, systolic blood pressure (accounting for anti-hypertensive treatment), history of diabetes, current cigarette smoking, prevalent cardiovascular disease (defined as history of myocardial infarction, angina pectoris, coronary insufficiency, intermittent claudication, or congestive heart failure), history of atrial fibrillation, and left ventricular hypertrophy. FSRP values range from 0 to 38 with higher values indicating worse vascular health risk (e.g., increased stroke risk). Note that the FSRP calculation is modified here because ECG measures (i.e., identifying left ventricular hypertrophy) are not available for NACC participants. In light of our prior work highlighting the incremental value of examining vascular health in a categorical manner versus just as a continuous variable [19], we considered FSRP both as a continuous and a categorical predictor.

Neuropsychological Assessment

Participants completed a protocol assessing multiple cognitive systems [22]. Neuropsychological performance, neurological examination results, and medical history details were used to diagnose participants at baseline. See Table 1 for more details on the neuropsychological protocol.

Table 1.

Neuropsychological Protocol

| Domain | Test | Range | NC** | MCI** | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Last Visit† | p-value | Baseline | Last Visit† | p-value | |||

| Global Cognition |

Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) [52] |

0–30 | 28.9±1.4 | 28.5±2.2 | <0.001 | 26.9±2.6 | 24.3±5.3 | <0.001 |

| Attention | Digit Span Forward [53] | 0–12 | 8.5±2.1 | 8.4±2.0 | <0.001 | 7.7±2.1 | 7.5±2.2 | <0.001 |

| Information Processing Speed |

Digit Symbol [53] | 0–93 | 47.4±12.5 | 46.0±14.0 | <0.001 | 37.2±12.3 | 32.5±14.4 | <0.001 |

| Trail Making Test Part A* [54] | 0–150 | 34.8±16.3 | 36.6±20.1 | <0.001 | 45.3±23.5 | 55.7±35.0 | <0.001 | |

| Executive Functioning |

Trail Making Test Part B* [54] | 0–300 | 91.4±50.9 | 102±64.2 | <0.001 | 142.5±77.6 | 168.7±89.4 | <0.001 |

| Digit Span Backward [53] | 0–12 | 6.8+2.3 | 6.7+2.3 | <0.001 | 5.7+2.1 | 5.2+2.2 | <0.001 | |

| Language | Boston Naming Test-30 Item (BNT-30) [55] | 0–30 | 26.9±3.4 | 26.9±4.0 | 0.073 | 24.1±5.1 | 22.5±6.6 | <0.001 |

| Animal Naming (Animals) [56] | n/a | 20.0±5.7 | 19.3±6.1 | <0.001 | 15.5±4.9 | 13.4±5.7 | <0.001 | |

| Vegetable Naming (Vegetables) [57] | n/a | 14.8±4.2 | 14.1±4.7 | <0.001 | 11.0±3.9 | 9.3±4.6 | <0.001 | |

| Episodic Memory |

Logical Memory Immediate Recall [53] | 0–25 | 13.5±3.9 | 14.1±4.5 | <0.001 | 8.9±4.2 | 7.7±5.1 | <0.001 |

| Logical Memory Delayed Recall [53] | 0–25 | 12.2±4.2 | 13.1±5.0 | <0.001 | 6.4±4.6 | 5.7±5.4 | <0.001 | |

Note.

lower scores denote better performance;

NC and MCI groups differ on all measures at baseline and last visit; p-values reflect within group changes from baseline to last visit;

for descriptive purposes only, the difference between last visit and baseline visit cognitive performance was compared; for hypothesis testing, generalized linear mixed models included neuropsychological data across all visits between the first and most recent (last) visit

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics for baseline clinical, baseline cognitive, and last visit cognitive variables were calculated for each diagnostic group (NC, MCI) and compared between groups using Kruskal-Wallis (for continuous variables) and Pearson’s chi-square tests (for categorical variables). For descriptive purposes only, the difference between last visit and baseline cognitive variables was compared to illustrate whether cognitive performance worsened over time in either group. Within each group, baseline clinical and cognitive variables were compared across FSRP quartile subgroups obtained from the combined population. Significance was set a priori at 0.05.

Prior to analyses, based on histogram evidence of a skewed distribution, logarithm transformations were taken for Trail Making Test Part A plus 1 and Trail Making Test Part B plus 1 to give each variable a more symmetrical distribution. Ordinary least squares regressions were used to relate FSRP first as a continuous variable and then as a categorical variable (i.e., FSRP Quartile group 1 (referent): 0–8, Quartile group 2: >8–11, Quartile group 3: >11–14, and Quartile group 4: >14–29) to cross-sectional cognitive variables. Generalized linear mixed models (GLMM) were used to model FSRP effects on longitudinal neuropsychological trajectories using neuropsychological data available across all visits between the first and most recent (last) UDS visit. Fixed effects for all models included baseline clinical characteristics (i.e., age, sex, education, race). For longitudinal models, follow-up period (i.e., time from first to most recent UDS visit) was also included as a fixed effect, and random effects included subject-specific intercept and slope for follow-up time. Histograms and residual plots were used to determine appropriate link function for GLMM. For modeling longitudinal trajectories, the identity link function was used for all outcomes.

Because age and sex are included in the FSRP calculation and age and sex were included as model covariates given their potential to independently confound neuropsychological performance, we assessed the impact of multicollinearity on results. First, we generated Spearman correlation coefficients between age (years) and FSRP score separately by diagnosis. Because results suggested potential multicollinearity (NC r=0.74; MCI r=0.63), we applied a more formal method of detection for multicollinearity using variance inflation factor (VIF). Results by diagnosis yielded a VIF<2.2 for all three variables, well below the suggested VIF>5 for defining multicollinearity [25]. Though multicollinearity was not detected, in post-hoc analyses, models were re-calculated using an age-excluded FSRP score to assess the effect of the remaining stroke risk factors on neuropsychological performance independent of age.

Significance was set a priori using a strict Bonferroni correction factor for each set of analyses (i.e., 0.0045 for 0.05/11 models per group). Analyses were conducted using R 2.14.1 (www.r-project.org). Note, for all results, a negative beta coefficient reflects worse cross-sectional performance or trajectory over time except for Trail Making Test Parts A and B, where positive beta coefficients reflect worse outcomes (i.e., both measures are speeded tasks).

Results

Participant Characteristics

At baseline, participants in the NC and MCI groups differed on all clinical characteristics, including age (F(1 ,9718)=145, p<0.001), sex (χ2=150, p<0.001), race (χ2=5.3, p=0.02), education (F(1,9718)=59, p<0.001), follow-up period (F(1,9718)=221, p<0.001) and number of observations (F(1,9718)=217, p<0.001). See Table 2. In addition, the NC and MCI groups differed on all cognitive variables at baseline, last visit, and changes over follow-up (all p-values<0.001). See Table 1 for baseline and longitudinal descriptive statistics for each diagnostic group.

Table 2.

Sample Characteristics

| NC n=6603 |

MCI n=3117 |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 72±8 | 74±8 | <0.001 |

| Sex, % Female | 68 | 56 | <0.001 |

| Race, % White | 80 | 77 | 0.021 |

| Education, years | 15.6±3 | 15±4 | <0.001 |

| Neuropsychological observations, total | 3.6±2.3 | 2.9±2.0 | <0.001 |

| Follow-up time,* years | 3.0±2.5 | 2.2±2.2 | <0.001 |

| FSRP, total risk points | 11.5±4.8 | 12.6±4.5 | <0.001 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 133±18 | 136±19 | <0.001 |

| Antihypertensive medications, % | 41 | 45 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes, % | 11 | 15 | <0.001 |

| Current smoker, % | 4 | 4 | 0.31 |

| History of CVD, % | 10 | 14 | <0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation, % | 6 | 6 | 0.21 |

| Age-excluded FSRP, total risk points | 5.7±3.3 | 6.2±3.4 | <0.001 |

Note.

defined as time between first and last UDS visit

Within each diagnostic group, participants differed on certain clinical characteristics when broken down into FSRP quartiles (see Table 3). Within the NC group, differences included baseline age (F(3,6599)=2333, p<0.001), race (χ2=28, p<0.001), education (F(3,6599)=74, p<0.001), follow-up period (F(3,6599)=7.6, p<0.001), and number of observations (F(3,6599)=11, p<0.001). Within MCI, differences included baseline age (F(3,3113)=664, p<0.001), race (χ2=17, p=0.001), education (F(3,3113)=11, p<0.001), and number of follow-up visits (F(3,3113)=2.6, p=0.048). Within each diagnostic category, participants differed on virtually all neuropsychological tests when examining across or between FSRP quartiles (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Baseline Within-Group Characteristics by FSRP Quartile

| NC | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | p-value | Total n=6603 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=1947 | n=2031 | n=1314 | n=1311 | |||

| Age, years | 64±5§‖# | 72±6‡‖# | 76±7‡§# | 80±6‡§‖ | <0.001 | 72±8 |

| Sex, % Female | 68 | 68 | 70 | 68 | 0.75 | 68 |

| Race, % White | 83‖# | 81# | 78‡ | 76‡§ | <0.001 | 80 |

| Education, years | 16±3§‖# | 16±3‡‖# | 15±3‡§# | 15±3‡§‖ | <0.001 | 15.6±3 |

| Neuropsychological observations, total |

3.4±2.2‖# | 3.6±2.3‡ | 3.8±2.3‡ | 3.7±2.2‡ | <0.001 | 3.6±2.3 |

| Follow-up time,* years | 2.8±2.5§‖# | 3.0±2.5 | 3.2±2.5 | 3.0±2.5 | <0.001 | 3.0±2.5 |

| Mini-Mental State Exam | 29.3±1.1§‖# | 29.0±1.3‡‖# | 28.7±1.5‡§# | 28.4±1.7‡§‖ | <0.001 | 28.9±1.4 |

| Digit Span Forward | 8.9±2.0§‖# | 8.5±2.1‡‖ | 8.3±2.1‡§ | 8.2±2.1‡§ | <0.001 | 8.5±2.1 |

| Digit Span Backward | 7.3±2.3§‖# | 6.8±2.2‡‖ | 6.4±2.3‡§ | 6.4±2.1‡§ | <0.001 | 6.8+2.3 |

| Digit Symbol Coding | 54.0±11.2§‖# | 47.9±11.6‡‖# | 43.5±11.2‡§# | 40.3±11.5‡§‖ | <0.001 | 47.4±12.5 |

| Trail Making Test Part A** | 28.8±11.2§‖# | 34.0±14.9‡‖# | 37.9±17.0‡§# | 42.1±19.9‡§‖ | <0.001 | 34.8±16.3 |

| Trail Making Test Part B** | 71.4±33.8§‖# | 88.6±47.4‡‖# | 101.0±53.6‡§# | 116.3±60.9‡§‖ | <0.001 | 91.4±50.9 |

| Animal Naming | 22.1±5.7§‖# | 20.1±5.5‡‖# | 19.0±5.4‡§# | 18.0±5.3‡§‖ | <0.001 | 20.0±5.7 |

| Vegetable Naming | 16.0±4.3§‖# | 14.9±4.2‡‖# | 14.2±4.0‡§# | 13.5±3.9‡§‖ | <0.001 | 14.8±4.2 |

| Boston Naming Test-30 item | 27.9±2.5§‖# | 27.0±3.3‡‖# | 26.6±3.5‡§# | 25.8±4.2‡§‖ | <0.001 | 26.9±3.4 |

| Logical Memory Immediate Recall | 14.3±3.6§‖# | 13.5±3.8‡‖# | 13.0±4.0‡§ | 12.7±4.0‡§ | <0.001 | 13.5±3.9 |

| Logical Memory Delayed Recall | 13.2±3.9§‖# | 12.2±4.1‡‖# | 11.7±4.3‡§# | 11.2±4.3‡§‖ | <0.001 | 12.2±4.2 |

| MCI | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | p-value | Total n=3117 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=549 | n=1022 | n=766 | n=780 | |||

| Age, years | 65±5§‖# | 73±6‡‖# | 77±7‡§# | 80±6‡§‖ | <0.001 | 74±8 |

| Sex, % Female | 55 | 54 | 60 | 55 | 0.07 | 56 |

| Race, % White | 80# | 80# | 78 | 72ठ| <0.001 | 78 |

| Education, years | 16±3‖# | 15±4# | 15±3 | 15±4‡§ | <0.001 | 15±4 |

| Neuropsychological observations, total |

2.9±2.0 | 3.0±2.0 | 2.9±2.0 | 2.7±1.8 | 0.05 | 2.9±2.0 |

| Follow-up time,* years | 2.2±2.2 | 2.3±2.2 | 2.2±2.2 | 2.0±2.1 | 0.10 | 2.2±2.2 |

| Mini-Mental State Exam | 27.4±2.3§‖# | 27.0±2.5‡# | 26.9±2.6‡# | 26.5±2.8‡§‖ | <0.001 | 26.9±2.6 |

| Digit Span Forward | 8.0±2.1# | 7.8±2.1 | 7.8±2.1 | 7.5±2.1‡ | 0.002 | 7.7±2.1 |

| Digit Span Backward | 6.1±2.3§‖# | 5.7±2.1‡ | 5.7±2.0‡ | 5.5±2.1‡ | <0.001 | 5.7+2.1 |

| Digit Symbol Coding | 41.6±12.5§‖# | 38.1±12.1‡‖# | 36.4±12.0‡§# | 33.5±11.4‡§‖ | <0.001 | 37.2±12.3 |

| Trail Making Test Part A** | 39.6±20.8§‖# | 43.8±22.5‡# | 45.5±22.1‡# | 51.3±26.3‡§‖ | <0.001 | 45.3±23.5 |

| Trail Making Test Part B** | 118.2±71.6§‖# | 138.7±76.0‡# | 145.7±77.0‡# | 162.2±79.3‡§‖ | <0.001 | 142.5±77.6 |

| Animal Naming | 16.9±5.1§‖# | 15.7±4.8‡# | 15.3±4.7‡# | 14.7±4.9‡§‖ | <0.001 | 15.5±4.9 |

| Vegetable Naming | 11.7±4.0§‖# | 10.9±4.0‡ | 11.0±3.8‡ | 10.7±3.6‡ | <0.001 | 11.0±3.9 |

| Boston Naming Test-30 item | 25.4±4.9§‖# | 24.1±5.1‡# | 23.8±5.2‡ | 23.6±5.1‡§ | <0.001 | 24.1±5.1 |

| Logical Memory Immediate Recall | 9.5±4.1§‖# | 8.8±4.3‡ | 8.8±4.1‡ | 8.4±4.1‡ | <0.001 | 8.9±4.2 |

| Logical Memory Delayed Recall | 7.2±4.8§‖# | 6.3±4.7‡‖# | 6.2±4.7 | 6.2±4.4 | 0.001 | 6.4±4.6 |

Note: Quartiles are mutually exclusive;

Follow-up is time from first to last UDS visit;

higher scores denote worse performance;

different from Q1,

different from Q2,

different from Q3,

different from Q4, all at p<0.05

FSRP & Cognition in NC

Among NC participants, elevated FSRP was cross-sectionally related to worse performance on a number of cognitive measures when correcting for multiple comparisons, including Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE; β=−0.02, p<0.0001), Digit Symbol Coding (β=−0.39, p<0.001), log Trail Making Test Part A (β=0.01, p<0.0001), log Trail Making Test Part B (β=0.01, p<0.0001), Animal Naming (β=−0.06, p=0.004), and Vegetable Naming (β=−0.04, p=0.003). See Table 4. All associations persisted when using an age-excluded FSRP score. See Supplementary Table 1.

Table 4.

Continuous FSRP and Cognitive Outcomes

| Cross-sectional Outcomes | NC | MCI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | 95% CI | p-value | β | 95% CI | p-value | |

| Mini-Mental State Exam | −0.02 | −0.03, −0.01 | <0.0001 | −0.01 | −0.03, 0.02 | 0.52 |

| Digit Span Forward | −0.01 | −0.03, 0.00 | 0.149 | −0.02 | −0.04, 0.00 | 0.10 |

| Digit Span Backward | −0.02 | −0.04, −0.01 | 0.007 | −0.02 | −0.04, 0.00 | 0.02 |

| Digit Symbol Coding | −0.39 | −0.47, −0.31 | <0.0001 | −0.12 | −0.24, 0.00 | 0.05 |

| Trail Making Test Part A (log)* | 0.01 | 0.01, 0.01 | <0.0001 | 0.002 | 0.00, 0.01 | 0.34 |

| Trail Making Test Part B (log)* | 0.01 | 0.01, 0.01 | <0.0001 | 0.01 | 0.00, 0.01 | 0.04 |

| Animal Naming | −0.06 | −0.09, −0.02 | 0.004 | 0.01 | −0.04, 0.06 | 0.80 |

| Vegetable Naming | −0.04 | −0.07, −0.02 | 0.003 | 0.02 | −0.02, 0.06 | 0.37 |

| Boston Naming Test-30 Item | −0.01 | −0.03, 0.01 | 0.431 | 0.07 | 0.03, 0.12 | 0.002 |

| Logical Memory Immediate Recall | −0.02 | −0.04, 0.01 | 0.222 | 0.002 | −0.04, 0.05 | 0.94 |

| Logical Memory Delayed Recall | −0.03 | −0.06, 0.00 | 0.067 | 0.04 | −0.01, 0.09 | 0.14 |

| Longitudinal Outcomes** | NC | MCI | ||||

| β | 95% CI | p-value | β | 95% CI | p-value | |

| Mini-Mental State Exam | −0.01 | −0.02, −0.01 | <0.0001 | 0.003 | −0.01, 0.02 | 0.67 |

| Digit Span Forward | −0.004 | −0.01, −0.002 | <0.0001 | 0.002 | −0.003, 0.01 | 0.47 |

| Digit Span Backward | −0.01 | −0.01, −0.01 | <0.0001 | 0.003 | −0.003, 0.01 | 0.34 |

| Digit Symbol Coding | −0.07 | −0.08, −0.06 | <0.0001 | 0.03 | −0.01, 0.06 | 0.10 |

| Trail Making Test Part A (log)* | 0.002 | 0.001, 0.002 | <0.0001 | 0.00 | −0.001, 0.001 | 0.86 |

| Trail Making Test Part B (log)* | 0.002 | 0.001, 0.002 | <0.0001 | 0.001 | −0.001, 0.002 | 0.36 |

| Animal Naming | −0.02 | −0.03, −0.02 | <0.0001 | 0.01 | −0.01, 0.02 | 0.18 |

| Vegetable Naming | −0.02 | −0.02, −0.01 | <0.0001 | −0.01 | −0.02, 0.01 | 0.29 |

| Boston Naming Test-30 item | −0.02 | −0.02, −0.01 | <0.0001 | 0.001 | −0.01, 0.02 | 0.88 |

| Logical Memory Immediate Recall | −0.02 | −0.03, −0.02 | <0.0001 | −0.01 | −0.02, 0.01 | 0.35 |

| Logical Memory Delayed Recall | −0.03 | −0.03, −0.02 | <0.0001 | −0.02 | −0.03, −0.01 | 0.004 |

Note: CI=confidence interval;

positive values denote worse performance;

longitudinal data presented as interaction term (time to follow-up*FSRP)

When analyzing FSRP quartiles in relation to cross-sectional outcomes, the highest (or worse vascular health) quartile as compared to the referent (i.e., healthiest quartile) was associated with worse performance on MMSE (β=−0.26, p<0.001), Digit Symbol Coding (β=−4.30, p<0.001), log Trail Making Test Part A (β=0.08, p<0.001), log Trail Making Test Part B (β=0.09, p<0.001), Animal Naming (β=−0.71, p=0.004), and Vegetable Naming (β=−0.58, p=0.002). The highest quartile compared to the lowest quartile differed for Digit Span Backward (β=−0.26, p=0.02), but this observation did not sustain correction for multiple comparison. See Table 5. A majority of associations persisted when using an age-excluded FSRP score, with the exception of Animal Naming (p=0.01) and Vegetable Naming (p=0.01), which did not survive correction for multiple comparisons. See Supplementary Table 2.

Table 5.

Categorical FSRP and Cross-sectional Cognitive Outcomes

| NC | Q2* | Q3* | Q4* | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | 95% CI | p-value | β | 95% CI | p-value | β | 95% CI | p-value | |

| Mini-Mental State Exam | 0.00 | −0.09, 0.09 | 0.99 | −0.12 | −0.23, 0.00 | 0.04 | −0.26 | −0.38, −0.13 | <0.001 |

| Digit Span Forward | −0.14 | −0.28, 0.00 | 0.05 | −0.18 | −0.35, 0.00 | 0.05 | −0.15 | −0.35, 0.04 | 0.12 |

| Digit Span Backward | −0.16 | −0.31, −0.01 | 0.04 | −0.32 | −0.51, −0.14 | <0.001 | −0.26 | −0.46, −0.05 | 0.02 |

| Digit Symbol Coding | −1.55 | −2.28, −0.82 | <0.001 | −3.28 | −4.19, −2.37 | <0.001 | −4.30 | −5.30, −3.29 | <0.001 |

| Trail Making Test Part A (log)** | 0.02 | 0.00, 0.04 | 0.10 | 0.04 | 0.01, 0.07 | 0.004 | 0.08 | 0.04, 0.11 | <0.001 |

| Trail Making Test Part B (log)** | 0.01 | −0.01, 0.04 | 0.32 | 0.04 | 0.003, 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.09 | 0.06, 0.13 | <0.001 |

| Animal Naming | −0.32 | −0.67, 0.04 | 0.08 | −0.52 | −0.96, −0.08 | 0.02 | −0.71 | −1.20, −0.22 | 0.004 |

| Vegetable Naming | −0.19 | −0.47, 0.08 | 0.17 | −0.31 | −0.65, 0.03 | 0.08 | −0.58 | −0.95, −0.20 | 0.002 |

| Boston Naming Test-30 Item | −0.02 | −0.23, 0.19 | 0.86 | 0.20 | −0.05, 0.46 | 0.12 | −0.20 | −0.49, 0.08 | 0.17 |

| Logical Memory Immediate Recall | −0.24 | −0.49, 0.02 | 0.07 | −0.31 | −0.63, 0.00 | 0.05 | −0.26 | −0.60, 0.09 | 0.15 |

| Logical Memory Delayed Recall | −0.19 | −0.47, 0.08 | 0.17 | −0.21 | −0.55, 0.13 | 0.22 | −0.30 | −0.67, 0.08 | 0.12 |

| MCI | Q2* | Q3* | Q4* | ||||||

| β | [95% CI] | p-value | β | [95% CI] | p-value | β | [95% CI] | p-value | |

| Mini-Mental State Exam | −0.11 | −0.39, 0.17 | 0.46 | 0.02 | −3.03, 0.34 | 0.92 | −0.15 | −0.49, 0.20 | 0.41 |

| Digit Span Forward | −0.19 | −0.42, 0.04 | 0.11 | −0.14 | −0.40, 0.12 | 0.30 | −0.32 | −0.61, −0.04 | 0.03 |

| Digit Span Backward | −0.31 | −0.53, −0.08 | 0.01 | −0.23 | −0.49, 0.02 | 0.08 | −0.36 | −0.64, −0.08 | 0.01 |

| Digit Symbol Coding | −0.48 | −1.74, 0.79 | 0.46 | −0.73 | −2.17, 0.71 | 0.32 | −1.84 | −3.42, −0.03 | 0.02 |

| Trail Making Test Part A (log)** | −0.002 | −0.05, 0.04 | 0.94 | −0.02 | −0.67, 0.04 | 0.53 | 0.04 | −0.02, 0.09 | 0.17 |

| Trail Making Test Part B (log)** | 0.05 | 0.00, 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.04 | −0.02, 0.10 | 0.19 | 0.10 | 0.03, 0.17 | 0.004 |

| Animal Naming | −0.30 | −0.84, 0.23 | 0.27 | −0.18 | −0.79, 0.43 | 0.56 | −0.34 | −1.00, 0.32 | 0.31 |

| Vegetable Naming | −0.30 | −0.72, 0.13 | 0.17 | −0.09 | −0.57, 0.39 | 0.71 | −0.09 | −0.61, 0.43 | 0.73 |

| Boston Naming Test-30 Item | −0.28 | −0.80, 0.24 | 0.29 | 0.02 | −0.57, 0.61 | 0.95 | 0.38 | −0.26, 1.02 | 0.24 |

| Logical Memory Immediate Recall | −0.24 | −0.71, 0.24 | 0.33 | −0.06 | −0.60, 0.49 | 0.84 | −0.19 | −0.78, 0.40 | 0.52 |

| Logical Memory Delayed Recall | −0.32 | −0.86, 0.21 | 0.24 | −0.17 | −0.78, 0.43 | 0.57 | 0.09 | −0.57, 0.75 | 0.79 |

Note: CI=confidence interval;

referent=Q1;

positive values denote worse performance

Among the NC participants, baseline FSRP was related to decline on all longitudinal cognitive outcomes over the follow-up period (all p-values<0.0001). See Table 4. When using an age-excluded FSRP score, associations with MMSE (p=0.001), Digit Symbol Coding (p<0.001), and Boston Naming (p<0.001) were retained, while associations for Digit Span Forward (p=0.03), Digit Span Backward (p=0.01), log Trail Making Test Part A (p=0.01), and Animal Naming (p=0.02) did not survive multiple correction comparison. See Supplementary Table 1.

Similarly, when examining FSRP effects categorically on trajectories, the highest quartile (or worse vascular health) was associated with longitudinal decline in all variables of interest as compared to the referent, including MMSE (β=−0.19, p<0.0001), Digit Span Forward (β=−0.05, p=0.001), Digit Span Backward (β=−0.09, p<0.0001), Digit Symbol Coding (β=−0.85, p<0.0001), log Trail Making Test Part A (β=0.02, p<0.0001), log Trail Making Test Part B (β=0.02, p<0.0001), Animal Naming (β=−0.30, p<0.0001), Vegetable Naming (β=−0.22, p<0.0001), Boston Naming Test (β=−0.23, p<0.0001), Logical Memory Immediate Recall (β=−0.29, p<0.0001), and Logical Memory Delayed Recall (β=−0.36, p<0.0001). The second and third quartile also differed from the referent with respect to decline on a subset of cognitive outcomes. See Table 6 for details. When using an age-excluded FSRP score, associations with MMSE (p=0.001), Digit Symbol Coding (p<0.001), and Boston Naming Test (p<0.001) persisted, while associations with Digit Span Backward (p=0.02), log Trail Making Test A (p=0.01), and Animal Naming (p=0.01) did not survive multiple comparison correction. See Supplementary Table 3.

Table 6.

Categorical FSRP and Longitudinal Cognitive Outcomes

| NC | Q2* | Q3* | Q4* | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | 95% CI | p-value | β | 95% CI | p-value | β | 95% CI | p-value | |

| Mini-Mental State Exam | −0.07 | −0.10, −0.03 | <0.001 | −0.08 | −0.12, −0.05 | <0.001 | −0.19 | −0.23, −0.15 | <0.001 |

| Digit Span Forward | −0.02 | −0.05, 0.004 | 0.11 | −0.03 | −0.06, 0.00 | 0.031 | −0.05 | −0.08, −0.02 | 0.001 |

| Digit Span Backward | −0.05 | −0.07, −0.02 | <0.001 | −0.06 | −0.09, −0.03 | <0.001 | −0.09 | −0.12, −0.06 | <0.001 |

| Digit Symbol Coding | −0.37 | −0.49, −0.24 | <0.001 | −0.58 | −0.72, −0.45 | <0.001 | −0.85 | −0.99, −0.71 | <0.001 |

| Trail Making Test Part A (log)** | 0.01 | 0.01, 0.02 | <0.001 | 0.02 | 0.01, 0.02 | <0.001 | 0.02 | 0.02, 0.03 | <0.001 |

| Trail Making Test Part B (log)** | 0.01 | 0.01, 0.02 | <0.001 | 0.02 | 0.01, 0.02 | <0.001 | 0.02 | 0.02, 0.03 | <0.001 |

| Animal Naming | −0.14 | −0.21, −0.06 | <0.001 | −0.22 | −0.30, −0.14 | <0.001 | −0.30 | −0.39, −0.22 | <0.001 |

| Vegetable Naming | −0.11 | −0.17, −0.05 | <0.001 | −0.18 | −0.25, −0.12 | <0.001 | −0.22 | −0.29, −0.15 | <0.001 |

| Boston Naming Test-30 Item | −0.04 | −0.09, 0.003 | 0.06 | −0.11 | −0.16, −0.06 | <0.001 | −0.23 | −0.28, −0.17 | <0.001 |

| Logical Memory Immediate Recall | −0.09 | −0.15, −0.03 | 0.01 | −0.21 | −0.28, −0.14 | <0.001 | −0.29 | −0.36, −0.22 | <0.001 |

| Logical Memory Delayed Recall | −0.13 | −0.20, −0.06 | <0.001 | −0.26 | −0.34, −0.19 | <0.001 | −0.36 | −0.43, −0.28 | <0.001 |

| MCI | Q2* | Q3* | Q4* | ||||||

| β | [95% CI] | p-value | β | [95% CI] | p-value | β | [95% CI] | p-value | |

| Mini-Mental State Exam | −0.26 | −0.45, −0.07 | 0.01 | −0.12 | −0.32, 0.08 | 0.24 | −0.07 | −0.28, 0.14 | 0.52 |

| Digit Span Forward | 0.11 | 0.05, 0.17 | <0.001 | 0.05 | −0.02, 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.07 | 0.01, 0.14 | 0.04 |

| Digit Span Backward | 0.09 | 0.02, 0.16 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.01, 0.15 | 0.03 | 0.04 | −0.04, 0.11 | 0.32 |

| Digit Symbol Coding | −0.004 | −0.43, 0.42 | 0.99 | 0.29 | −0.16, 0.74 | 0.21 | 0.27 | −0.19, 0.74 | 0.25 |

| Trail Making Test Part A (log)** | 0.002 | −0.01, 0.02 | 0.86 | −0.004 | −0.02, 0.01 | 0.69 | 0.001 | −0.02, 0.02 | 0.88 |

| Trail Making Test Part B (log)** | 0.01 | −0.01, 0.03 | 0.23 | 0.01 | −0.01, 0.03 | 0.31 | 0.01 | −0.01, 0.03 | 0.21 |

| Animal Naming | 0.04 | −0.15, 0.23 | 0.70 | 0.07 | −0.13, 0.27 | 0.48 | 0.11 | −0.10, 0.31 | 0.30 |

| Vegetable Naming | −0.04 | −0.19, 0.11 | 0.58 | −0.05 | −0.20, 0.11 | 0.57 | −0.09 | −0.25, 0.08 | 0.30 |

| Boston Naming Test-30 Item | −0.18 | −0.38, 0.02 | 0.07 | −0.09 | −0.30, 0.12 | 0.40 | −0.03 | −0.24, 0.18 | 0.80 |

| Logical Memory Immediate Recall | −0.12 | −0.28, 0.03 | 0.12 | −0.13 | −0.30, 0.03 | 0.11 | −0.08 | −0.25, 0.09 | 0.37 |

| Logical Memory Delayed Recall | −0.2 | −0.36, −0.05 | 0.01 | −0.14 | −0.31, 0.02 | 0.08 | −0.26 | −0.42, −0.09 | 0.003 |

Note: Data presented as interaction term (time to follow-up*FSRP quartile);

CI=confidence interval;

referent=Q1;

positive values denote worse performance

FSRP & Cognition in MCI

Among MCI participants, FSRP associations with worse Digit Span Backward (p=0.02) Digit Symbol Coding (p=0.05), and log Trail Making Test B performance (p=0.04) did not persist following correction for multiple comparisons. See Table 4 for details. Interestingly, an elevated FSRP was cross-sectionally related to better performance on Boston Naming Test (β=0.07, p=0.002), an association that persisted when using the age-excluded FSRP score (p=0.003). See Supplementary Table 1. Given this counterintuitive finding, post-hoc analyses explored potential interactions and yielded mostly null results, including age-excluded FSRP × education (p=0.41), age-excluded FSRP × sex (p=0.41), and age-excluded FSRP × race (p=0.96). There was a nominal age-excluded FSRP × age interaction (p=0.03). Follow-up analyses examining age by quartile suggest an inverted association between FSRP and Boston Naming Test 30-item performance for the oldest participants (age 75–80 quartile: β=0.13, p=0.01; age 80–90 quartile: β=0.12, p=0.01), compared to the youngest participants (age 55–69 quartile: β=−0.13, p=0.78).

When treating FSRP as a categorical variable in the regression models, the highest quartile compared to the referent was cross-sectionally associated with slower log Trail Making Test Part B performance (β=0.10, p=0.004). Cross-sectional associations which did not survive multiple comparison correction were noted between the highest quartile and the referent for Digit Span Forward (p=0.03), Digit Span Backward (p=0.01), and Digit Symbol Coding (p=0.02). See Table 5. When using an age-excluded FSRP score, the association with log Trail Making Test Part B did not survive multiple correction comparison (p=0.04). See Supplementary Table 2.

Baseline FSRP was associated with worse trajectory among the MCI participants on Logical Memory Delayed Recall (β=−0.02, p=0.004). See Table 4. When using an age-excluded FSRP score, this finding did not persist (p=0.51). See Supplementary Table 1.

When analyzing FSRP as a categorical variable, the highest (worse vascular health) quartile was associated with longitudinal decline in Logical Memory Delayed Recall (β=−0.26, p=0.003). See Table 6. When using an age-excluded FSRP score, this observation did not persist (p=0.19). See Supplementary Table 3.

Discussion

This study provides a comprehensive analysis of the association between an index for stroke risk (FSRP) and cognitive abilities in older adults with a cognitive diagnosis of either NC or MCI. Among the NC participants, higher stroke risk (especially the highest FSRP quartile) was related to worse cross-sectional performances on a subset of variables, including global cognition, information processing speed, working memory, and sequencing abilities. Increased FSRP was also associated with cognitive decline among the NC participants for all outcomes examined, including global cognition, working memory, information processing speed, sequencing, verbal fluency, and episodic memory abilities. These results, which cannot be explained by age, suggest that adverse vascular health risk is associated with modest declines in cognitive health among cognitively normal older adults. In contrast, among the MCI participants, higher stroke risk (especially the highest FSRP quartile) was modestly related only to sequencing abilities at baseline and delayed episodic memory decline over the follow-up, observations that appear to be associated in part by advancing age. That is, age appears to strengthen the stroke risk estimate even when controlling for the association between age and neuropsychological performance or change over time.

Collectively, results suggest increased vascular risk is associated with poorer cross-sectional and longitudinal neuropsychological health, which is consistent with evidence that concomitant cerebrovascular disease accelerates the clinical manifestation of AD pathology [26–28]. The present findings are particularly relevant to the current dominating theoretical model of AD pathophysiology, which puts forth a temporal ordering of dynamic biomarkers seen in “pure” AD [29]. Despite mounting neuropathological evidence that AD rarely exists without concomitant cerebrovascular disease among older adults [30–32], the model does not incorporate the contribution of cerebrovascular health. Given the current results implicate vascular risk factors as a correlate of neuropsychological decline in the earliest portion of the cognitive aging spectrum, theoretical models of AD pathophysiology would benefit from a more inclusive representation of mechanisms contributing to AD neuropathology, clinical manifestation of neuropsychological symptoms, and progression over time.

It also appears that worse systemic vascular health may has the greatest effect on cognitive decline among elders with normal cognition as compared to individuals who are already clinically manifesting AD pathology (i.e., diagnosed with MCI). There are several plausible explanations accounting for the disparity of findings between groups. First, the follow-up interval among the MCI cohort was approximately seven months shorter than that of the NC cohort, possibly contributing to a shorter window for cognitive decline among the MCI group. However, the difference between baseline and last visit outcomes suggests the MCI group declined significantly faster on all outcomes compared to the NC group (data not shown). Second, a floor effect in the MCI cohort might contribute to the absence of findings, yet visual inspection of the data confirmed a wide range of performance across the MCI participants. A more plausible explanation is that an adverse vascular risk profile has a greater effect on brain aging for individuals with normal cognition compared to MCI. That is, worse systemic vascular health may have circumscribed effects on cognitive trajectory (i.e., limited to worsening episodic memory performance) among elders with prodromal AD who are thought to have extensive amyloid accumulation and tau aggregation (rather than cerebrovascular disease) accounting for their cognitive changes [29]. Finally, the source and type of MCI cohort we studied may also account for the disparate findings between the MCI and NC cohorts. That is, we relied on a cohort of MCI participants with a predominant amnestic profile (i.e., Petersen criteria), which may contribute to differences in how vascular health affects brain health [33]. Plus, utilization of MCI participants from an Alzheimer’s Disease Center network likely yields a referral bias where individuals with cognitive complaints or early objective cognitive changes are less likely to have vascular mechanisms underlying such changes than if participants were identified through a community-based cohort [34]. Future work should more precisely characterize the role of vascular risk factors on cognitive decline across strictly controlled MCI subtypes.

The mechanism(s) underlying our observed associations between elevated FSRP and worse cognitive outcomes are likely multifactorial and may include the clinical manifestations of unrecognized cerebrovascular disease. For example, systemic vascular disease is associated with reductions in cerebral blood flow [35], silent cortical infarcts [36,37], white matter hyperintensities [38], and microbleeds [39]. Such structural changes related to cerebrovascular disease likely contributed to the observed variation across all cognitive variables among the NC participants. Unfortunately, neuroimaging data that might confirm this hypothesis are not readily available for this dataset.

While the observed effects for the NC group are statistically significant, it is noteworthy that some of these effects are relatively small in magnitude. For example, in mixed model analysis the beta coefficient for FSRP and Logical Memory Immediate Recall is −0.02 while the beta coefficient for age and Logical Memory Immediate Recall is −0.07 (data not shown). By comparison, the effect of FSRP on Logical Memory Immediate Recall performance is equivalent to more than 3 months of advanced cognitive aging. A similar effect is present for FSRP and Logical Memory Delayed Recall (i.e., more than 4 months of advanced cognitive aging). In contrast, the beta coefficient for FSRP and Digit Symbol Coding is −0.07 while the beta coefficient for age and Digit Symbol Coding is −0.47 (data not shown). A comparison of these results suggests the effect of FSRP on Digit Symbol Coding performance is equivalent to approximately 2 months of advanced cognitive aging. The small effects observed in the current study may be secondary to the late life nature of the cohort, such that the window of vascular injury on brain health occurs earlier in mid-life [40,41]. Furthermore, the modest effect we observed might be compounded over several decades of aging given life expectancy in the United States extends late into the eighth decade. Future work with extensive follow-up intervals will provide clarity on the long-term cognitive implications of effects reported in the current study. The small effects observed may also be due to a restriction of range of vascular risk or disease in our sample due to our exclusion of clinical stroke and transient ischemic attack and the Alzheimer’s Disease Center network referral bias mentioned above [34]. Effects of vascular health on cognitive outcomes may be larger when studying a more representative sample.

It is notable that demographic factors differed by FSRP categorical values. That is, participants with higher (worse) FSRP values were more likely to be older (which was expected given increasing age earns more points in the stroke risk profile), non-white, and have lower education levels at baseline as compared to the healthier FSRP values. These findings align with previous studies reporting a higher prevalence of cardiovascular comorbidities in minority elders in comparison to whites [42]. Socio-economic factors contributing to such health disparities may include an earlier age of onset or treatment differences for chronic health conditions among minorities [43,44]. Also, education attainment is often used as a proxy measure for socioeconomic status or health literacy and has been linked to cardiovascular health [45]. Given the higher burden of CVD among minorities and the established link between impaired cardiovascular health and dementia risk, additional research is needed to examine how multiple cardiovascular comorbities influence cognitive trajectories in these populations.

One observation from the current study that warrants brief discussion is the cross-sectional association between FSRP and Boston Naming Test 30-item performance in MCI. While inspection of the raw-unadjusted mean Boston Naming Test 30-item performance by FSRP quartile suggests more adverse vascular risk corresponds to poorer naming performance, the fully adjusted models suggest it is associated with better naming performance. To understand this counterintuitive finding, we examined interaction terms between age-excluded FSRP and age, sex, education, and race, but only age emerged as a significant (albeit weak) interaction term. Follow-up analyses suggest the counterintuitive effect was present in participants age 75 and older. It is plausible that the ambiguous FSRP and naming observation may be due to a more complex multi-variable interaction or confound not captured with our available methods. Replication is needed to better understand this finding.

The current study enhances the existing literature in several important ways. First, much of the existing literature has not considered the differential impact of diagnostic status (i.e., brains at risk in the normal cognition or MCI phase of cognitive aging). Second, inclusion of both cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses offers an opportunity to reconcile prior inconsistencies in the literature. Third, most prior work examining vascular health in relation to brain aging has emphasized a “silo” approach by focusing on one single risk factor, such as blood pressure [46]. However, vascular health is a complex construct, which is supported by formal guidelines for managing cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease suggesting more emphasis on risk prediction models incorporating multiple vascular factors. Finally, continuous FSRP models suggest increasing adverse vascular risk is associated with worse cognitive trajectory across all neuropsychological measures of interest among cognitively normal elders. Examination of the categorical FSRP models illustrates there is an incremental effect of adverse vascular risk on certain cognitive outcomes like global cognition, information processing speed, and fluency production over time. By contrast, only the most adverse vascular risk category (i.e., Quartile 4 in comparison to Quartile 1) relates to attention decrements over time among cognitively normal elders. Thus, as we have previously shown [19], examining systemic vascular health as both a continuous and categorical variable provides rich information to better understand associations between vascular health and brain aging.

Additional strengths of the current study include our leveraging of the extensive NACC UDS dataset which included standard cognitive diagnostic criteria applied across participating sites and enabled assessment of vascular health in relation to both general cognition and specific cognitive systems. Finally, the study’s longitudinal follow-up permitted analysis of FSRP in relation to cognitive trajectory, providing power to identify novel effects and reconciling ambiguous results from prior longitudinal work [11,47].

There are some methodological limitations to the current manuscript that warrant discussion. First, participants comprising the NACC dataset are predominantly White and well-educated and reflect a convenience sample, which limits generalizability. The use of a highly educated population is noteworthy because participants’ FSRP values may be lower given the well-educated cohort, reflecting better vascular health [48–50]. There was a relatively short mean follow-up time (2 to 3 years), but we believe the large sample size (n=9720) offers sufficient power to detect valid changes in cognition and function within this time period. Reliance on a modified version of the FSRP may have underestimated vascular health issues in the current sample given that LVH prevalence among adults age 50 and older ranges from 14% to 48% [51]. Similarly, the reliance on self-report for some elements of the FSRP may have contributed unwanted variance in the dataset. Finally, assessment of episodic memory in NACC is restricted to immediate and delayed story paragraph recall. The inability to assess associations between vascular risk and learning or recognition poses a methodological limitation.

In summary, our findings suggest that underlying vascular health (as measured by a risk factor score) is associated with cognitive decline in cognitively normal elders. Inexpensive and easily determined vascular risk health information may serve as an informative and cost-effective risk stratification tool for more detailed and costly assessments and interventions. Future studies should incorporate subtypes of cognitive impairment to better understand associations between adverse vascular health and cognitive outcomes. Integration of neuroimaging and other biomarkers in future work will provide key information regarding mechanisms underlying the associations observed here. Longitudinal research will also determine whether favorable modification of a patient’s vascular risk profile modifies cognitive trajectory.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Funding Sources

This research was supported by K23-AG030962 (Paul B. Beeson Career Development Award in Aging; ALJ); K24-AG046373 (ALJ); Alzheimer’s Association IIRG-08–88733 (ALJ); R01-HL11516 (ALJ); R01-AG034962 (ALJ); T32-MH65215 (TJH); Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America Foundation Fellowship in Translational Medicine and Therapeutics (TJH); Alzheimer’s Association NIRG-13–283276 (KAG); American Federation for Aging Research Medical Student Training in Aging Research Grant (JS; T35-AG038027); the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (U01-AG016976); and the Vanderbilt Memory & Alzheimer’s Center.

Footnotes

Disclosures

None

References

- 1.Kivipelto M, Laakso MP, Tuomilehto J, Nissinen A, Soininen H. Hypertension and hypercholesterolaemia as risk factors for Alzheimer's disease: Potential for pharmacological intervention. CNS Drugs. 2002;16:435–444. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200216070-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arvanitakis Z, Wilson RS, Bienias JL, Evans DA, Bennett DA. Diabetes mellitus and risk of Alzheimer disease and decline in cognitive function. Arch Neurol. 2004;61:661–666. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.5.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ott A, Slooter AJ, Hofman A, van Harskamp F, Witteman JC, Van Broeckhoven C, van Duijn CM, Breteler MM. Smoking and risk of dementia and Alzheimer's disease in a population-based cohort study: The Rotterdam study. Lancet. 1998;351:1840–1843. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)07541-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bangen KJ, Restom K, Liu TT, Jak AJ, Wierenga CE, Salmon DP, Bondi MW. Differential age effects on cerebral blood flow and bold response to encoding: Associations with cognition and stroke risk. Neurobiol Aging. 2009;30:1276–1287. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bell RD, Zlokovic BV. Neurovascular mechanisms and blood-brain barrier disorder in Alzheimer's disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2009;118:103–113. doi: 10.1007/s00401-009-0522-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Toledo Ferraz Alves TC, Scazufca M, Squarzoni P, de Souza Duran FL, Tamashiro-Duran JH, Vallada HP, Andrei A, Wajngarten M, Menezes PR, Busatto GF. Subtle gray matter changes in temporo-parietal cortex associated with cardiovascular risk factors. J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;27:575–589. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-110827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jeerakathil T, Wolf PA, Beiser A, Massaro J, Seshadri S, D'Agostino RB, DeCarli C. Stroke risk profile predicts white matter hyperintensity volume: The Framingham study. Stroke. 2004;35:1857–1861. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000135226.53499.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brady CB, Spiro A, McGlinchey-Berroth R, 3rd, Milberg W, Gaziano JM. Stroke risk predicts verbal fluency decline in healthy older men: Evidence from the normative aging study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2001;56:P340–P346. doi: 10.1093/geronb/56.6.p340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elias MF, Sullivan LM, D'Agostino RB, Elias PK, Beiser A, Au R, Seshadri S, DeCarli C, Wolf PA. Framingham stroke risk profile and lowered cognitive performance. Stroke. 2004;35:404–409. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000103141.82869.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wolf PA, D'Agostino RB, Belanger AJ, Kannel WB. Probability of stroke: A risk profile from the Framingham study. Stroke. 1991;22:312–318. doi: 10.1161/01.str.22.3.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaffashian S, Dugravot A, Elbaz A, Shipley MJ, Sabia S, Kivimaki M, Singh-Manoux A. Predicting cognitive decline: A dementia risk score vs. The Framingham vascular risk scores. Neurology. 2013;80:1300–1306. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31828ab370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Llewellyn DJ, Lang IA, Xie J, Huppert FA, Melzer D, Langa KM. Framingham stroke risk profile and poor cognitive function: A population-based study. BMC Neurol. 2008;8:12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-8-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maineri Nde L, Xavier FM, Berleze MC, Moriguchi EH. Risk factors for cerebrovascular disease and cognitive function in the elderly. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2007;89:142–146. doi: 10.1590/s0066-782x2007001500003. 158–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaffashian S, Dugravot A, Brunner EJ, Sabia S, Ankri J, Kivimaki M, Singh-Manoux A. Midlife stroke risk and cognitive decline: A 10-year follow-up of the whitehall II cohort study. Alzheimers Dement. 2012;9:572–579. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Albert MS, Dekosky ST, Dickson D, Dubois B, Feldman HH, Fox NC, Gamst A, Holtzman DM, Jagust WJ, Petersen RC, Snyder PJ, Carrillo MC, Thies B, Phelps CH. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer's disease: Recommendations from the national institute on aging-Alzheimer's association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers & Dementia. 2011;7:270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Groot JC, de Leeuw FE, Oudkerk M, van Gijn J, Hofman A, Jolles J, Breteler MM. Cerebral white matter lesions and cognitive function: The Rotterdam scan study. Ann Neurol. 2000;47:145–151. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(200002)47:2<145::aid-ana3>3.3.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buckner RL. Memory and executive function in aging and ad: Multiple factors that cause decline and reserve factors that compensate. Neuron. 2004;44:195–208. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qiu C, Cotch MF, Sigurdsson S, Jonsson PV, Jonsdottir MK, Sveinbjrnsdottir S, Eiriksdottir G, Klein R, Harris TB, van Buchem MA, Gudnason V, Launer LJ. Cerebral microbleeds, retinopathy, and dementia: The ages-reykjavik study. Neurology. 2010;75:2221–2228. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182020349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jefferson AL, Himali JJ, Beiser AS, Au R, Massaro JM, Seshadri S, Gona P, Salton CJ, DeCarli C, O'Donnell CJ, Benjamin EJ, Wolf PA, Manning WJ. Cardiac index is associated with brain aging: The Framingham heart study. Circulation. 2010;122:690–697. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.905091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beekly DL, Ramos EM, Lee WW, Deitrich WD, Jacka ME, Wu J, Hubbard JL, Koepsell TD, Morris JC, Kukull WA. The National Alzheimer's Coordinating Center (NACC) database: The uniform data set. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2007;21:249–258. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e318142774e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): Current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43:2412–2414. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.11.2412-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weintraub S, Salmon D, Mercaldo N, Ferris S, Graff-Radford NR, Chui H, Cummings J, DeCarli C, Foster NL, Galasko D, Peskind E, Dietrich W, Beekly DL, Kukull WA, Morris JC. The Alzheimer's disease centers' Uniform Data Set (UDS): The neuropsychologic test battery. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2009;23:91–101. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e318191c7dd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petersen RC. Mild cognitive impairment as a diagnostic entity. J Intern Med. 2004;256:183–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.D'Agostino RB, Wolf PA, Belanger AJ, Kannel WB. Stroke risk profile: Adjustment for antihypertensive medication. The Framingham study. Stroke. 1994;25:40–43. doi: 10.1161/01.str.25.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O'Brien RM. A caution regarding rules of thumb for variance inflation factors. Qual Quant. 2007;41:673–690. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li J, Wang YJ, Zhang M, Xu ZQ, Gao CY, Fang CQ, Yan JC, Zhou HD Chongqing Ageing Study G. Vascular risk factors promote conversion from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2011;76:1485–1491. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318217e7a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van der Flier WM, van der Vlies AE, Weverling-Rijnsburger AW, de Boer NL, Admiraal-Behloul F, Bollen EL, Westendorp RG, van Buchem MA, Middelkoop HA. MRI measures and progression of cognitive decline in nondemented elderly attending a memory clinic. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;20:1060–1066. doi: 10.1002/gps.1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rossi R, Geroldi C, Bresciani L, Testa C, Binetti G, Zanetti O, Frisoni GB. Clinical and neuropsychological features associated with structural imaging patterns in patients with mild cognitive impairment. Dement Geriatr Cogn. 2007;23:175–183. doi: 10.1159/000098543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jack CR, Jr, Knopman DS, Jagust WJ, Petersen RC, Weiner MW, Aisen PS, Shaw LM, Vemuri P, Wiste HJ, Weigand SD, Lesnick TG, Pankratz VS, Donohue MC, Trojanowski JQ. Tracking pathophysiological processes in Alzheimer's disease: An updated hypothetical model of dynamic biomarkers. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:207–216. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70291-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schneider JA, Arvanitakis Z, Bang W, Bennett DA. Mixed brain pathologies account for most dementia cases in community-dwelling older persons. Neurology. 2007;69:2197–2204. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000271090.28148.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schneider JA, Bennett D. Where vascular meets neurodegenerative disease. Stroke. 2010;41:S144–S146. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.598326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Troncoso JC, Zonderman AB, Resnick SM, Crain B, Pletnikova O, O'Brien RJ. Effect of infarcts on dementia in the Baltimore longitudinal study of aging. Ann Neurol. 2008;64:168–176. doi: 10.1002/ana.21413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Delano-Wood L, Bondi MW, Sacco J, Abeles N, Jak AJ, Libon DJ, Bozoki A. Heterogeneity in mild cognitive impairment: Differences in neuropsychological profile and associated white matter lesion pathology. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2009;15:906–914. doi: 10.1017/S1355617709990257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schneider JA, Aggarwal NT, Barnes L, Boyle P, Bennett DA. The neuropathology of older persons with and without dementia from community versus clinic cohorts. J Alzheimers Dis. 2009;18:691–701. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Petersen P, Kastrup J, Videbaek R, Boysen G. Cerebral blood flow before and after cardioversion of atrial fibrillation. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1989;9:422–425. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1989.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ezekowitz MD, James KE, Nazarian SM, Davenport J, Broderick JP, Gupta SR, Thadani V, Meyer ML, Bridgers SL. Silent cerebral infarction in patients with nonrheumatic atrial fibrillation. The veterans affairs stroke prevention in nonrheumatic atrial fibrillation investigators. Circulation. 1995;92:2178–2182. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.8.2178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leys D, Erkinjuntti T, Desmond DW, Schmidt R, Englund E, Pasquier F, Parnetti L, Ghika J, Kalaria RN, Chabriat H, Scheltens P, Bogousslavsky J. Vascular dementia: The role of cerebral infarcts. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1999;3(13 Suppl):S38–S48. doi: 10.1097/00002093-199912003-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.de Leeuw FE, de Groot JC, Oudkerk M, Witteman JC, Hofman A, van Gijn J, Breteler MM. Hypertension and cerebral white matter lesions in a prospective cohort study. Brain. 2002;125:765–772. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hara M, Yakushiji Y, Nannri H, Sasaki S, Noguchi T, Nishiyama M, Hirotsu T, Nakajima J, Hara H. Joint effect of hypertension and lifestyle-related risk factors on the risk of brain microbleeds in healthy individuals. Hypertens Res. 2013;36:789–794. doi: 10.1038/hr.2013.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carmelli D, Swan GE, Reed T, Wolf PA, Miller BL, DeCarli C. Midlife cardiovascular risk factors and brain morphology in identical older male twins. Neurology. 1999;52:1119–1124. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.6.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Swan GE, DeCarli C, Miller BL, Reed T, Wolf PA, Jack LM, Carmelli D. Association of midlife blood pressure to late-life cognitive decline and brain morphology. Neurology. 1998;51:986–993. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.4.986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mensah GA, Mokdad AH, Ford ES, Greenlund KJ, Croft JB. State of disparities in cardiovascular health in the united states. Circulation. 2005;111:1233–1241. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000158136.76824.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Levine DA, Lewis CE, Williams OD, Safford MM, Liu K, Calhoun DA, Kim Y, Jacobs DR, Jr, Kiefe CI. Geographic and demographic variability in 20-year hypertension incidence: The CARDIA study. Hypertension. 2011;57:39–47. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.160341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hertz RP, Unger AN, Ferrario CM. Diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia in Mexican Americans and non-Hispanic whites. Am J Prev Med. 2006;30:103–110. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Boykin S, Diez-Roux AV, Carnethon M, Shrager S, Ni H, Whitt-Glover M. Racial/ethnic heterogeneity in the socioeconomic patterning of CVD risk factors: In the United States: The multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2011;22:111–127. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2011.0001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gifford KA, Badaracco M, Liu D, Tripodis Y, Gentile A, Lu Z, Palmisano J, Jefferson AL. Blood pressure and cognition among older adults: A meta-analysis. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2013;28:649–664. doi: 10.1093/arclin/act046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dregan A, Stewart R, Gulliford MC. Cardiovascular risk factors and cognitive decline in adults aged 50 and over: A population-based cohort study. Age Ageing. 2013;42:338–345. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afs166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Diez-Roux AV, Nieto FJ, Muntaner C, Tyroler HA, Comstock GW, Shahar E, Cooper LS, Watson RL, Szklo M. Neighborhood environments and coronary heart disease: A multilevel analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;146:48–63. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Smith GD, Hart C, Watt G, Hole D, Hawthorne V. Individual social class, area-based deprivation, cardiovascular disease risk factors, and mortality: The Renfrew and Paisley study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998;52:399–405. doi: 10.1136/jech.52.6.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jefferson AL, Massaro JM, Beiser AS, Seshadri S, Larson MG, Wolf PA, Au R, Benjamin EJ. Inflammatory markers and neuropsychological functioning: The Framingham heart study. Neuroepidemiology. 2011;37:21–30. doi: 10.1159/000328864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Levy D, Anderson KM, Savage DD, Kannel WB, Christiansen JC, Castelli WP. Echocardiographically detected left ventricular hypertrophy: Prevalence and risk factors. The Framingham heart study. Ann Intern Med. 1988;108:7–13. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-108-1-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pfeffer RI, Kurosaki TT, Harrah CH, Jr, Chance JM, Filos S. Measurement of functional activities in older adults in the community. J Gerontol. 1982;37:323–329. doi: 10.1093/geronj/37.3.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wechsler D. Wechsler memory scale-revised, Psychological Corporation. Texas: San Antonio; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Reitan RM. Validity of the trail making test as an indicator of organic brain damage. Percept Motor Skill. 1958;8:271–276. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kaplan E, Goodglass H, Weintraub S. The Boston naming test. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Goodglass H, Kaplan E. The assessment of aphasia and related disorders. Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Febiger; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Troyer AK, Moscovitch M, Winocur G. Clustering and switching as two components of verbal fluency: Evidence from younger and older healthy adults. Neuropsychology. 1997;11:138–146. doi: 10.1037//0894-4105.11.1.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.