Abstract

HIV testing in prison settings has been identified as an important mechanism to detect cases among high-risk, underserved populations. Several public health organizations recommend that testing across healthcare settings, including prisons, be delivered in an opt-out manner. However, implementation of opt-out testing within prisons may pose challenges in delivering testing that is informed and understood to be voluntary. In a large state prison system with a policy of voluntary opt-out HIV testing, we randomly sampled adult prisoners in each of seven intake prisons within two weeks after their opportunity to be HIV tested. We surveyed prisoners’ perception of HIV testing as voluntary or mandatory and used multivariable statistical models to identify factors associated with their perception. We also linked survey responses to lab records to determine if prisoners’ test status (tested or not) matched their desired and perceived test status. Thirty eight percent (359/936) perceived testing as voluntary. The perception that testing was mandatory was positively associated with age less than 25 years (adjusted relative risk [aRR]: 1.45, 95% CI: 1.24, 1.71) and preference that testing be mandatory (aRR: 1.81, 95% CI: 1.41, 2.31), but negatively associated with entry into one of the intake prisons (aRR: 0.41 95% CI: 0.27, 0.63). Eighty-nine percent of prisoners wanted to be tested, 85% were tested according to their wishes, and 82% correctly understood whether or not they were tested. Most prisoners wanted to be HIV tested and were aware that they had been tested, but less than 40% understood testing to be voluntary. Prisoners’ understanding of the voluntary nature of testing varied by intake prison and by a few individual-level factors. Testing procedures should ensure that opt-out testing is informed and understood to be voluntary by prisoners and other vulnerable populations.

Keywords: HIV testing, prison, opt-out, informed consent, voluntary

Introduction

The incidence of HIV infection in the US has been largely unchanged over the past 10 years with approximately 50,000 cases reported annually (Prejean et al., 2011). In response, the HIV “Seek, Test, Treat, and Retain,” (STTR) strategy, in which infected individuals are identified through HIV testing and then engaged in ongoing treatment and counseling, has been advocated as an approach to reduce the transmission rate of HIV, slowing the spread of the epidemic (Hayden, 2010). A pillar of the strategy is employment of HIV testing among high risk, hard to reach, and often times vulnerable populations, including criminal justice-involved populations (National Institutes for Health, 2010). An estimated 14% of HIV-positive persons in the US pass through a prison or jail annually (Spaulding et al., 2009), and the prevalence of HIV among state prisoners is three times the national average (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Maruschak & Beavers, 2009), however, the vast majority of these infections occur in the community (Rich et al., 2011).

In 2006, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommended that all healthcare settings, including prisons, provide HIV testing in an opt-out manner (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2006). Unlike opt-in testing, opt-out testing does not require pre-test counseling or a signed informed consent. Instead, the patient is notified that testing will be conducted unless the patient declines.

In response to the CDC’s recommendations there have been concerns—largely unverified—that opt-out testing is prone to incorrect implementation, leading to testing without patients’ full knowledge or consent (Celada, Merchant, Waxman, & Sherwin, 2011). These concerns may be particularly germane to testing in prisons, where individual autonomy is inherently limited(Rosen, Schoenbach, & Kaplan, 2006; Seal, Eldridge, Zack, & Sosman, 2010; Walker et al., 2004), and indeed, about half of US state prison systems have policies mandating that prisoners be tested for HIV (Maruschak & Beavers, 2009).

In prison systems with policies of voluntary HIV testing, the change from opt-in to opt-out testing has been reported to increase the proportion of prisoners tested for HIV. When opt-out was implemented in the Washington and North Carolina (NC) prison systems, the proportion tested increased from 72% and 59%, respectively, to over 90% in both states (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011; Wohl et al., 2012). The proportion tested in states that have maintained opt-in testing among US prisoners, however, range from 39% to 84% (Andrus et al., 1989; Behrendt et al., 1994; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011; Cotten-Oldenburg, Jordan, Martin, & Sadowski, 1999; Hoxie et al., 1998; Kassira et al., 2001). Reported proportions of routine opt-out testing among non-pregnant adults in other US healthcare settings have primarily come from studies of rapid oral testing in emergency departments, and generally range from 17% to 65% (Batey et al., 2012; Brown et al., 2008; Brown et al., 2007; Cunningham et al., 2009; Du, Camacho, Zurlo, & Lengerich, 2011; Wheatley et al., 2011; White et al., 2011).

While the proportion of inmates tested for HIV has been observed to increase with opt-out HIV screening, it remains unclear whether this streamlined approach to testing reduces patients’ awareness that the test is voluntary and that opting-out is an option. To better understand the delivery of opt-out HIV testing in the correctional setting, we surveyed prisoners’ perceptions of the voluntary and informed nature of opt-out HIV testing and examined factors related to prisoners’ perception of testing as voluntary or mandatory.

Methods

This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and by the North Carolina Department of Public Safety, Division of Adult Correction.

Setting: HIV testing upon entry to the NC prison system

At the time of the survey, 2010–2011, the following was intended to occur according to the prison system’s protocol: For the first two to three weeks of their incarceration, adult prisoners were sent to one of seven intake (i.e., processing) prisons, depending on the inmates’ conviction type, sentence length, county of arrest, gender, and age; an eighth facility predominantly incarcerates minors. At the intake prisons, nurses were to review prisoners’ medical histories and read aloud a statement of general consent for medical care, including HIV testing. The consent included the passage: “I hereby voluntarily consent to medical and/or dental examinations, treatments and procedures which are deemed necessary in the opinion of my physician and health care providers, including tuberculosis, syphilis, HIV infection, laboratory tests and x-rays.” Tuberculosis and syphilis tests were mandatory for all prisoners, but the HIV test was not. After being read the statement, prisoners were asked to sign the consent form. It was permissible for prisoners to ask questions or to ask for the consent to be re-read. Following the general consent, the nurse filled out a “Refusal of Services for HIV Testing Only” form which included the question: “After being read the general consent [form] did the inmate request to opt-out of (refuse) routine HIV testing?” The nurse then drew blood for the mandatory syphilis test, and if the prisoner did not opt-out, an additional blood specimen was drawn for the HIV test. In three intake prisons, inmates attended an HIV education class, although depending on the timing of their entry, some prisoners were offered the opportunity to test for HIV prior to the class. In 2008–2009, the seroprevalence of HIV in the NC prison system was 1.45% (Wohl et al., 2012).

Prisoner survey eligibility and recruitment

From April 2010 to March 2011, we sampled prisoners from the seven intake prisons that predominantly housed those aged 18 years or older. We developed recruitment goals for each intake prison so that the distribution of intake prisons among the study population would reflect the distribution of intake prisons among all prison entrants. Within each intake prison, potential participants were selected randomly from a roster of prisoners. Study eligibility criteria were: 1) age 18 years or older; 2) English-speaking; 3) not housed in solitary confinement or disciplinary segregation; 4) completed all prison health processing activities; 5) two weeks or less had passed since being offered the opportunity to test for HIV; and 6) could provide informed consent to participate. Consenting prisoners were administered surveys via audio computer-assisted self-interviews with touch screen computers. A research assistant was present to help participants navigate the survey. Respondents did not receive any compensation or other incentives for participating in the survey.

Study outcomes

Survey items were generated by our study team which included experts in both HIV and correctional health. Items were written at a fourth-grade reading level and, using an iterative process, were field tested with 30 inmates using cognitive interviewing to establish prisoners’ comprehension of each item. The surveys were then piloted with approximately 100 prisoners prior to initiating the main study.

Our primary outcome was prisoners’ perception of HIV testing in prison as voluntary or mandatory. Specifically, prisoners were asked to choose how testing was conducted in their intake prison. Response options were: “Inmates have a choice whether or not to get tested for HIV,” which was coded as “Voluntary,” or, “All inmates have to be tested for HIV – they do not have a choice,” which was coded as “Mandatory.” Other responses were collapsed into a single category, “Other.” Participants were then asked whether “inmates should have a choice” to be tested or whether “all inmates should be tested for HIV – they should not have a choice.”

Our secondary outcomes included desired testing status (wanted to be tested or not) at prison entry and awareness of testing status (thought tested or thought not tested) during intake (see Appendix 1 for survey items). For each of these items, we assessed whether prisoners’ responses agreed with their testing status (tested or not), as documented in the prison system’s electronic records.

Additional domains queried in the survey relevant to our analysis included prisoners’ demographics, number of previous incarcerations, HIV knowledge (alpha =0.75 to 0.89; r = 0.76 to 0.94) (Carey & Schroder, 2002), perceived risk for HIV infection, attendance of the HIV prison course, and pre-incarceration HIV testing history.

Analysis of survey data

We compared the demographic characteristics of our respondent population with those of all adult prisoners admitted during the same period. Then, given the variation in prisoner characteristics across intake prisons, we examined the distribution of our outcomes across each of the seven adult intake prisons and used chi-square tests to assess for differences in these frequencies across intake prisons. We also conducted analyses to examine whether responses for our primary and secondary outcomes differed based on whether or not prisoners had received their test result prior to taking the survey; among respondents who received their test result prior to taking the survey, we examined whether responses differed based on participants’ reported test result (positive or negative).

We explored factors associated with our primary outcome of interest, prisoners’ perceptions of the testing policy as voluntary or mandatory, using bivariate and multivariable models. We first examined the bivariate association between our outcome, coded as mandatory or not mandatory, and each of the following domains: intake prison, demographics, HIV knowledge, risk behaviors, incarceration history, prison HIV course attendance, preferred testing policy (mandatory or voluntary), and any prior HIV testing. In the multivariable analysis, we included only variables found to have statistically significant bivariate associations (p < 0.05) with the outcome. All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.2 (Cary, North Carolina).

Results

Enrollment rate and participant characteristics

Of the approximately 25,000 prisoners who entered the prison system during the study period, we randomly selected and approached 1,812 to participate in the study. Fifty-five percent (1,000/1,812) of those approached provided written informed consented to participate. However, for our analysis, we excluded 64 respondents (11 who reported testing HIV-positive prior to prison entry, 2 who—contrary to protocol— were surveyed prior to their testing opportunity in prison, and 51 who were missing data for the primary outcome because of non-response). Accordingly, we had an analytic population of 936 for our main analysis examining perception of testing policy. The distributions of intake prison, age, and race for our sample generally were similar to those for all prison entrants during roughly the same time period (Table 1).

Table 1.

Selected demographic characteristics of all prison entrants and of survey respondents, NC prison system, 2010–2011

| Intake Prison | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | F2 | M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | M5 | ||

|

All entrants (n=27,407)a |

||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Across prisons | n, (%) | 1352 (4.9) | 2091 (7.6) | 1772 (6.5) | 6121 (22.3) | 7840 (28.6) | 5528 (20.2) | 2703 (9.9) |

|

| ||||||||

| Within prison | % Black | 37.3 | 35.8 | 52.7 | 63.5 | 48.7 | 47.1 | 65.4 |

|

| ||||||||

| Age, years (median) | 34 | 32 | 35 | 32 | 36 | 30 | 20 | |

|

| ||||||||

|

Survey Respondents (n=936)b |

||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Across prisons | n, (%) | 45 (4.8) | 77 (8.2) | 60 (6.4) | 224 (23.9) | 260 (27.8) | 183 (19.6) | 87 (9.3) |

|

| ||||||||

| Within prison | % Black | 24.4 | 35.1 | 45.0 | 57.6 | 46.2 | 44.3 | 63.2 |

|

| ||||||||

| Age, years (median) | 32 | 31 | 38 | 33 | 35 | 35 | 20 | |

Based on public data, July 2010 to June 2011

Survey respondents with data for the primary outcome, April 2010 to March 2011

F, Female prison; M, Male prison; NC, North Carolina

Across our study population, 87% of respondents were male, 48% were Black, and half were between the ages of 25 and 40 years (Table 2). Before this incarceration, more than 80% had been in a prison or jail and 80% were tested for HIV prior to this incarceration. Six percent perceived themselves to be at high risk for HIV infection. According to prison records, 95% of survey respondents were tested for HIV at entry, with estimates ranging by intake prison from 90% to 98%, p<0.05.

Table 2.

Characteristics of survey respondents incarcerated in the NC prison system, 2010–2011

| Characteristics | Level | n | % | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 122 | 13.0 | 10.9, 15.2 |

| Male | 814 | 87.0 | 84.8, 89.1 | |

|

| ||||

| Race | Black | 450 | 48.1 | 44.9, 51.3 |

| White | 404 | 43.2 | 40.0, 46.3 | |

| Other | 82 | 8.8 | 7.0, 10.6 | |

|

| ||||

| Age groupa (years) | < 25 | 222 | 23.8 | 21.1, 26.6 |

| 25 – 40 | 468 | 50.2 | 47.0, 53.4 | |

| 41+ | 242 | 26.0 | 23.2, 28.8 | |

|

| ||||

| Educationa | < HS | 353 | 37.9 | 34.8, 41.0 |

| HS or GED | 356 | 38.2 | 35.1, 41.4 | |

| >HS | 222 | 23.9 | 21.1, 26.6 | |

|

| ||||

| Prior Incarcerations | Yes | 773 | 82.6 | 80.2, 85.0 |

| No | 156 | 16.7 | 14.3, 19.1 | |

| Missing | 7 | 0.8 | 0.2, 1.3 | |

|

| ||||

| Risk Percepetiona,b | Low | 456 | 49.6 | 46.4, 52.9 |

| Moderate | 410 | 44.6 | 41.4, 47.8 | |

| High | 53 | 5.8 | 4.3, 7.3 | |

|

| ||||

| HIV testing prior to this incarcerationa | Yes | 752 | 81.2 | 78.7, 83.7 |

| No | 174 | 18.8 | 16.3, 21.3 | |

|

| ||||

| Admission prison | M1 | 60 | 6.4 | 4.8, 8.0 |

| M2 | 224 | 23.9 | 21.2, 26.7 | |

| M3 | 260 | 27.8 | 24.9, 30.7 | |

| M4 | 183 | 19.6 | 17.0, 22.1 | |

| M5 | 87 | 9.3 | 7.4, 11.2 | |

| F1 | 45 | 4.8 | 3.4, 6.2 | |

| F2 | 77 | 8.2 | 6.5, 10.0 | |

|

| ||||

| HIV Course in Prison | Attended | 597 | 63.8 | 60.7, 66.9 |

| Not Attended | 339 | 36.2 | 33.1, 39.3 | |

|

| ||||

| HIV Knowledgec | Low | 75 | 8.0 | 6.3, 9.8 |

| High | 861 | 92.0 | 90.3, 93.7 | |

|

| ||||

| Wanted to be tested at prison intake | Yes | 833 | 89.3 | 87.3, 91.3 |

| No | 100 | 10.7 | 8.7, 12.7 | |

|

| ||||

| HIV testing at prison intakea,b | Yes | 884 | 94.6 | 93.1, 96.0 |

| No | 51 | 5.5 | 4.0, 6.9 | |

|

| ||||

| Prisoners perception of testing status | Tested | 796 | 85.0 | 82.8, 87.3 |

| Not Tested | 110 | 11.8 | 9.7, 13.8 | |

| Don’t know | 30 | 3.2 | 2.1, 4.3 | |

|

| ||||

| Preferred testing strategy | Mandatory | 789 | 84.3 | 82.0, 86.6 |

| Voluntary | 147 | 15.7 | 13.4, 18.0 | |

|

| ||||

| Perception of prison testing policy | Mandatory | 514 | 54.9 | 51.7, 58.1 |

| Voluntary | 359 | 38.4 | 35.2, 41.5 | |

| Other | 63 | 6.7 | 5.1, 8.3 | |

Two percent or less of data were missing; percentage and 95%CI corresponds to non-missing data

Risk perception: I don’t do things that put me at risk for HIV: Disagree a lot (= High), Agree a little or Disagree a little ( = Moderate), Agree a lot (= Low)

“Low” defined as a mean score of < 0.5 and represents the 10th percentile or lower

Based on prison electronic records

CI, Confidence Interval; F, female prison; HS, High School; GED, General Equivalency Diploma; M, male prison

Perception of testing policy, desired testing policy, perception of testing status, and desired testing status

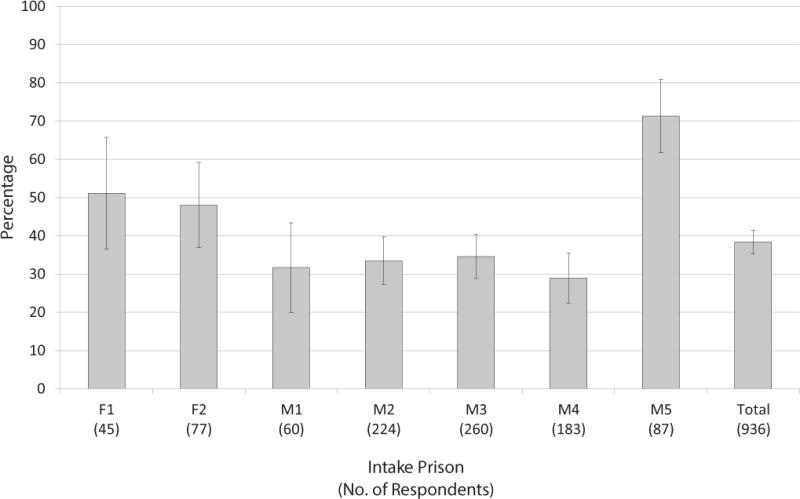

Overall, 38% (n=359) of prisoners perceived that HIV testing was voluntary, with proportions differing significantly (p<0.05) across facilities from 29% to 71% (Figure 1). Eighty-four percent of prisoners reported that HIV testing should be mandatory, 89% reported that they had wanted to be tested at entry, and 85% thought they had been tested at entry (Table 2); of these last three measures, only perception of testing status differed by intake prison, with estimates ranging from 50% to 96%, p<0.05.

Figure 1.

Percentage of NC prisoners who thought that HIV testing at intake was voluntary, 2010–2011

Prisoners who reported receiving their test result prior to the survey (n=453) were more likely than other prisoners to perceive testing as voluntary (40% vs. 30%, p<0.05) and to report wanting a test (94% vs. 89%, p<0.05). A few participants (n=9) reported receiving a positive result from their prison HIV test prior to being administered the survey. Among these nine prisoners, the proportion perceiving the testing policy as voluntary (33%) and the proportion wanting to be tested (89%) were similar to those for other respondents.

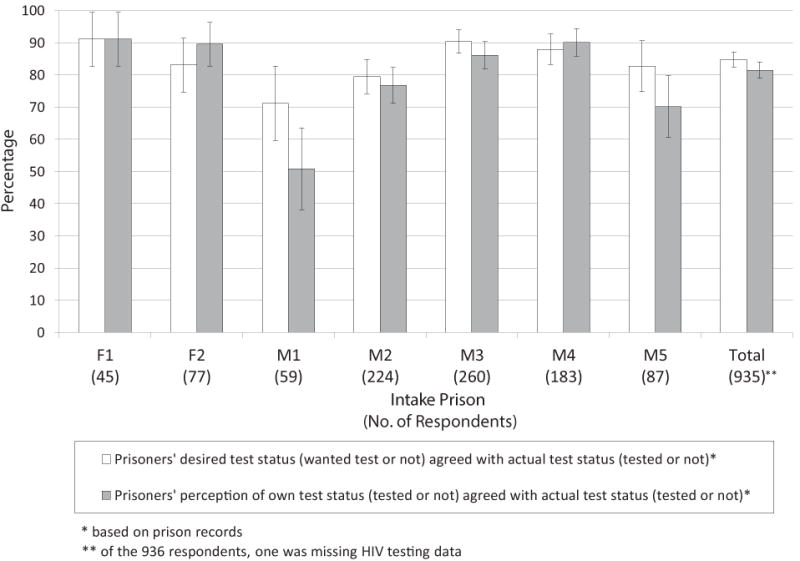

Agreement between prisoners’ test status (tested or not) with their desired and perceived test status

Eighty five percent of prisoners were tested according to what they reported in the survey that they had wanted, with percentages ranging from 71–91% across intake prisons (p<0.05, Figure 2). Eighty-two percent correctly perceived whether they were tested or not, with proportions ranging from 51% to 91% across intake prisons (p<0.05). Among the 16% of prisoners for whom perceived and actual test status differed, 71% (102/143) had been tested, but thought they had not. Among this population, 71% (72/102) reported that they had wanted to be tested for HIV.

Figure 2.

Percentage agreement between HIV test status* (tested or not) and perceived and desired test status

Multivariable assessment of factors associated with the perception that testing was mandatory

In the multivariable analysis of testing policy, those aged less than 25 years (adjusted Relative Risk [aRR]: 1.45, 95% CI: 1.24, 1.71) and those who preferred that testing be mandatory (aRR: 1.81, 95% CI: 1.41, 2.31) were more likely than other prisoners to perceive that testing in prison was mandatory. Further, respondents in intake prison M5 were less than half as likely (aRR: 0.41, 95% CI: 0.27, 0.63) as those in in the referent intake prison (M1) to report that testing was mandatory (Table 3).

Table 3.

Associations with the perception that HIV testing is mandatory upon entry to the NC prison system, 2010–2011

| Characteristic | Level | RR | 95% CI | p-value | aRRa | 95% CIs | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 0.87 | 0.71, 1.05 | 0.1420 | |||

| Male | 1 | ||||||

|

| |||||||

| Race | Black | 0.92 | 0.81, 1.03 | 0.1600 | |||

| Other | 0.91 | 0.73, 1.14 | 0.4018 | ||||

| White | 1 | ||||||

|

| |||||||

| Age group (years) | <25 | 1.16 | 0.97, 1.38 | 0.1065 | 1.45 | 1.24, 1.71 | <.0001 |

| 25 – 40 | 1.20 | 1.03, 1.39 | 0.0196 | 1.14 | 0.99, 1.33 | 0.0768 | |

| 41+ | 1 | 1 | |||||

|

| |||||||

| Education | < HS | 1.03 | 0.88, 1.20 | 0.7513 | |||

| HS or GED | 1.05 | 0.90, 1.22 | 0.5475 | ||||

| >HS | 1 | ||||||

|

| |||||||

| Prior Incarcerations | Yes | 1.09 | 0.92, 1.28 | 0.3215 | |||

| No | 1 | ||||||

|

| |||||||

| Risk Perceptiona | High | 0.90 | 0.67, 1.21 | 0.4710 | |||

| Moderate | 1.12 | 0.99, 1.26 | 0.0680 | ||||

| Low | 1 | ||||||

|

| |||||||

| HIV testing prior to this incarceration | Yes | 1.06 | 0.91, 1.24 | 0.4430 | |||

| No | 1 | ||||||

|

| |||||||

| Admission prison | M1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| M2 | 1.14 | 0.87, 1.51 | 0.3457 | 1.05 | 0.77, 1.44 | 0.7414 | |

| M3 | 1.18 | 0.90, 1.55 | 0.2418 | 1.08 | 0.80, 1.45 | 0.6201 | |

| M4 | 1.32 | 1.01, 1.74 | 0.0452 | 1.19 | 0.87, 1.63 | 0.2783 | |

| M5 | 0.53 | 0.34, 0.81 | 0.0039 | 0.41 | 0.27, 0.63 | <.0001 | |

| F1 | 0.89 | 0.59, 1.34 | 0.5764 | 0.89 | 0.60, 1.33 | 0.5736 | |

| F2 | 1.01 | 0.72, 1.42 | 0.9399 | 0.99 | 0.72, 1.36 | 0.9594 | |

|

| |||||||

| HIV Knowledgeb | Low | 0.92 | 0.73, 1.15 | 0.4594 | |||

| High | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| HIV Course in Prison | Attended | 1.35 | 1.18, 1.55 | <.0001 | 1.08 | 0.88, 1.31 | 0.4708 |

| Not Attended | 1 | 1 | |||||

|

| |||||||

| Preferred testing policy | Mandatory | 2.49 | 1.51, 2.49 | <.0001 | 1.81 | 1.41, 2.31 | <.0001 |

| Voluntary | 1 | 1 | |||||

Note: Boldface indicates statistical significance, p <0.05

aRR, adjusted relative risk; CI, confidence interval; F, female prison; HS, high school; GED, General Equivalency Diploma; M, male prison;

Risk perception: I don’t do things that put me at risk for HIV: Disagree a lot (= High), Agree a little or Disagree a little ( = Moderate), Agree a lot (= Low)

“Low” defined as a mean score of < 0.5 and represents the 10th percentile or lower

Discussion

The risk of inadequate informed consent with the opt-out approach to HIV testing is of renewed relevance with the implementation of the STTR strategy. The risks of inadequate consent are of particular salience to correctional populations, for whom autonomy is explicitly limited and screening for other infections may be mandatory.

Most prisoners were tested in accordance with their preferences and accurately understood whether or not they were tested, but less than 40% reported that testing was voluntary. The difficulty in communicating the voluntary nature of testing likely resulted, at least in part, from the ambiguity of the consent. Although the consent refers to HIV testing as “voluntary,” so too were tests for syphilis and TB, which were actually mandatory.

Prisoners’ understanding of the testing policy was not consistent across all intake prisons. Prisoners in intake prison M5 were much more likely than other prisoners to understand that testing was voluntary. It is notable that in brief site visits of the intake prisons conducted 1–2 years prior to the survey (2 visits per facility, each approximately 2–3 hours in duration, 3–4 weeks apart, and documented with a standardized observation form), we observed that M5 was the only intake prison in which nurses always asked prisoners if they wanted the test; in the other prisons, the nurses never asked prisoners if they wanted to opt-out. While there are limitations in the use of these observations to interpret our survey findings, the consistency between the observations and our survey findings may provide some context for prisoners’ experiences. In light of possible confusion caused by the consent form, patient-provider communication may have played an important role in prisoners’ understanding that opt-out testing was voluntary. The lack of a relationship between most individual-level variables and prisoners’ perception of testing policy further supports the importance of patient-provider interaction in conveying the voluntary nature of opt-out testing.

Few studies have examined the process by which opt-out HIV testing is provided in any setting. Of the two existing studies we identified, both also indicated inadequate communication about the voluntary nature of opt-out HIV testing (Haukoos et al., 2012; Ujiji et al., 2011). In a study of opt-out prenatal HIV testing among Kenyan women, all women were tested (except when testing kits were unavailable), and only 17% perceived that testing was voluntary (Ujiji et al., 2011). In a US study of ambulatory emergency department patients randomized to receive via computer kiosk either an opt-out or an opt-in offer to be tested for HIV, 53% of those who accepted testing under the opt-out condition later reported that they were unaware of their acceptance; only 3% who agreed to testing under the opt-in condition were unaware of their acceptance (Haukoos et al., 2012). These studies suggest that the failure to adequately explain to those being tested that opt-out HIV testing is voluntary is not unique to correctional settings.

Although there may be concern that greater communication about one’s right to refuse testing may diminish testing rates, our data demonstrating that the vast majority of prisoners wanted to be tested for HIV suggest that HIV testing rates among prisoners would remain high if testing options were conveyed more successfully.

In addition to most prisoners holding a personal desire to be tested, nearly 85% reported that HIV testing should be mandatory, a finding similar to that from a 1990s survey of Rhode Island released prisoners (Ramratnam et al., 1997). Several organizations, including the CDC, American Public Health Association, and the World Health Organization are opposed to mandatory testing, in large part due to concerns that prisoners testing positive may be subjected to stigma and discrimination (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2003; National Comission on Correctional Health Care, 2003; UNAIDS, 1999). Nevertheless, the number of state prison systems with policies of mandatory HIV testing has increased over time (Maruschak & Beavers, 2001, 2009), and in 2013 NC passed legislation mandating testing of all prisoners. While the effects of mandatory testing policies on stigma and discrimination among prisoners has not been studied systematically, results from our 2008–09 HIV sero-survey of NC prisoners suggest that such policies will increase statewide annual HIV case detection by less than 2% (North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services Communicable Disease Branch, 2009; Wohl et al., 2012).

This study has some limitations. Prisoners’ perceptions of HIV testing may be heavily influenced by the nurse they encountered for the general medical consent and HIV test., but data identifying the nurse who conducted each prisoner’s general consent, was unavailable for analysis. Additionally, the surveys were conducted after prisoners’ opportunities for HIV testing; accordingly, reported desire to be tested at entry may have been influenced by whether or not the respondent was tested. Although this effect could not be assessed, we did find that among those who thought that they had been tested, receiving a test result had only a modest effect on our outcomes. Another consideration is that the participation “rate” from our survey was lower than desired, although not unexpected given the lack of remuneration, and it was consistent with findings from several population based epidemiologic studies (Galea & Tracy, 2007). The rate also suggests that potential respondents understood that study participation was voluntary. Further, the demographic characteristics of the study population were similar to those of the entire population of prison entrants, providing some support for the generalizability of our results to non-participants; however, selection bias remains an important consideration. Although our findings may be system-specific, the study provides a model for possible evaluations of opt-out HIV testing in other state prison systems.

Conclusion

In summary, under an opt-out HIV testing policy, less than 40% of prisoners understood that they could refuse testing. A high proportion of prisoners were tested in accordance with their wishes, wanted to be HIV tested, and endorsed mandatory HIV screening for inmates upon entry. Difficulty conveying the voluntary nature of opt-out testing is unlikely to be specific to either HIV or prison settings, but given the importance of HIV screening in correctional facilities, approaches that deliver greater clarity in the consent process and improve provider-patient communication are needed. Such approaches must aim to provide opt-out testing in a manner that does not forfeit individuals’ knowledge or autonomy, while maintaining the high proportions of HIV testing achieved with the opt-out strategy.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kelly Green, MPH, for her contribution as the study coordinator. We also thank Gail Henderson, PhD, and Stuart Rennie, PhD, for providing thoughtful feedback on the manuscript. We dedicate this article to our friend, colleague, and mentor, the late Andrew H. Kaplan, MD.

This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health under Grant R01MH079720 and by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Center for AIDS Research (CFAR), an NIH funded program P30 AI50410

Appendix 1. Survey items addressing HIV testing within the prison intake centers

| Construct | Item | Response Options* |

|---|---|---|

| Main outcome | ||

| Perceived testing policy | Here is a list of some ways HIV testing may be done at this processing center. Please listen to these descriptions and choose which is most like the way HIV testing is done here? |

|

| Secondary outcomes | ||

| Perceived testing status (thought tested or thought not tested) | Since you’ve been at this processing center, have you been tested for HIV? |

|

| Desired testing status | During processing did you want to have an HIV test? |

|

| Other selected constructs | ||

| Testing preference | Which of the following is most like how you think HIV testing should be done here |

|

| Risk Perception | I don’t do things that put me at risk for getting HIV |

|

References

- Andrus JK, Fleming DW, Knox C, McAlister RO, Skeels MR, Conrad RE, Foster LR. HIV testing in prisoners: is mandatory testing mandatory? Am J Public Health. 1989;79(7):840–842. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.79.7.840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batey DS, Hogan VL, Cantor R, Hamlin CM, Ross-Davis K, Nevin C, Willig JH. Short communication routine HIV testing in the emergency department: assessment of patient perceptions. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2012;28(4):352–356. doi: 10.1089/aid.2011.0074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrendt C, Kendig N, Dambita C, Horman J, Lawlor J, Vlahov D. Voluntary testing for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in a prison population with a high prevalence of HIV. Am J Epidemiol. 1994;139(9)(95):918–926. 90093–4. doi: 10.1016/1353-1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J, Kuo I, Bellows J, Barry R, Bui P, Wohlgemuth J, Parikh N. Patient perceptions and acceptance of routine emergency department HIV testing. Public Health Rep. 2008;123(Suppl 3):21–26. doi: 10.1177/00333549081230S304. Retrieved from PubMed (19172703) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J, Shesser R, Simon G, Bahn M, Czarnogorski M, Kuo I, Sikka N. Routine HIV screening in the emergency department using the new US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines – Results from a high-prevalence area. Jaids-Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2007;46(4):395–401. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181582d82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey MP, Schroder KE. Development and psychometric evaluation of the brief HIV Knowledge Questionnaire. AIDS Educ Prev. 2002;14(2):172–182. doi: 10.1521/aeap.14.2.172.23902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celada MT, Merchant RC, Waxman MJ, Sherwin AM. An ethical evaluation of the 2006 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Recommendations for HIV testing in health care settings. Am J Bioeth. 2011;11(4):31–40. doi: 10.1080/15265161.2011.560339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV in the United States: An Overview [Web page] Retrieved December 8, 2012 from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/factsheets/us_overview.htm.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, editor. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Advancing HIV prevention: Interim Technical Guidance for Selected Interventions. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2003. pp. 25–30. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2006. Revised Recommendations for HIV Testing of Adults, Adolescents, and Pregnant Women in Health-Care Settings. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Screening of Male Inmates During Prison Intake Medical Evaluation — Washington, 2006–2010. MMWR. 2011;60(24):811–813. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotten-Oldenburg NU, Jordan BK, Martin SL, Sadowski LS. Voluntary HIV testing in prison: do women inmates at high risk for HIV accept HIV testing? AIDS Educ Prev. 1999;11(1):28–37. Retrieved from PubMed (10070587) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham CO, Doran B, DeLuca J, Dyksterhouse R, Asgary R, Sacajiu G. Routine opt-out HIV testing in an urban community health center. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009;23(8):619–623. doi: 10.1089/apc.2009.0005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du P, Camacho F, Zurlo J, Lengerich EJ. Human immunodeficiency virus testing behaviors among US adults: the roles of individual factors, legislative status, and public health resources. Sex Transm Dis. 2011;38(9):858–864. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31821a0635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea S, Tracy M. Participation rates in epidemiologic studies. [Review] Ann Epidemiol. 2007;17(9):643–653. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haukoos JS, Hopkins E, Bender B, Al-Tayyib A, Long J, Harvey J, for the Denver Emergency Department, HIVTRC Use of Kiosks and Patient Understanding of Opt-out and Opt-in Consent for Routine Rapid Human Immunodeficiency Virus Screening in the Emergency Department. Acad Emerg Med. 2012;19(3):287–293. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2012.01290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayden EC. ‘Seek, test and treat’ slows HIV. Nature. 2010;463(7284):1006. doi: 10.1038/4631006a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoxie NJ, Chen MH, Prieve A, Haase B, Pfister J, Vergeront JM. HIV seroprevalence among male prison inmates in the Wisconsin Correctional System. WMJ. 1998;97(5):28–31. Retreived from PubMed (9617305) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassira EN, Bauserman RL, Tomoyasu N, Caldeira E, Swetz A, Solomon L. HIV and AIDS surveillance among inmates in Maryland prisons. J Urban Health. 2001;78(2):256–263. doi: 10.1093/jurban/78.2.256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruschak LM, Beavers R. HIV in Prisons and Jails, 1999. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Maruschak LM, Beavers R. HIV in Prisons 2007–08. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- National Comission on Correctional Health Care. Standards for Health Services in Correctional Institutions. 3. Washington, DC: American Public Health Association; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- National Institutes for Health. Unprecedented effort to seek, test, and treat inmates with HIV: NIH research to improve public health with focus on prison and jail systems across the United States. [Web page] NIH News. 2010 Retrieved Septemeber 23, 2010 from http://www.nih.gov/news/health/sep2010/nida-23.htm.

- North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services Communicable Disease Branch. 2008 HIV/STD Surveillance Report. 2009:1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Prejean J, Song R, Hernandez A, Ziebell R, Green T, Walker F, Hall HI. Estimated HIV incidence in the United States 2006–2009. PLoS One. 2011;6(8):e17502. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramratnam B, Rich JD, Parkh A, Tsoulfas G, Vigilante KC, Flanigan TP. Former prisoners’ views on mandatory HIV testing during incarceration. Journal of Correctional Health Care. 1997;4(2):155–164. doi: 10.1177/107834589700400205. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rich JD, Wohl DA, Beckwith CG, Spaulding AC, Lepp NE, Baillargeon J, Springer S. HIV-related research in correctional populations: now is the time. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2011;8(4):288–296. doi: 10.1007/s11904-011-0095-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen DL, Schoenbach VJ, Kaplan AH. HIV testing in state prisons: balancing human rights and public health. [Review] Infectious Diseases in Corrections Report. 2006;9(4):1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Seal DW, Eldridge GD, Zack B, Sosman J. HIV testing and treatment with correctional populations: people, not prisoners. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21(3):977–985. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spaulding AC, Seals RM, Page MJ, Brzozowski AK, Rhodes W, Hammett TM. HIV/AIDS among inmates of and releasees from US correctional facilities, 2006: declining share of epidemic but persistent public health opportunity. PLoS One. 2009;4(11):e7558. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ujiji OA, Rubenson B, Ilako F, Marrone G, Wamalwa D, Wangalwa G, Ekstrom AM. Is ‘Opt-Out HIV Testing’ a real option among pregnant women in rural districts in Kenya? BMC Public Health. 2011;11 doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS. WHO guidelines on HIV infection and AIDS in prisons. Geneva: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Walker J, Sanchez R, Davids J, Stevens M, Whitehorn L, Greenspan J, Mealey R. Is routine testing mandatory or voluntary? [Correspondence] Clnical Infectious Diseases. 2004;40:319. doi: 10.1086/426147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheatley MA, Copeland B, Shah B, Heilpern K, Del Rio C, Houry D. Efficacy of an emergency department-based HIV screening program in the Deep South. J Urban Health. 2011;88(6):1015–1019. doi: 10.1007/s11524-011-9588-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White DA, Scribner AN, Vahidnia F, Dideum PJ, Gordon DM, Frazee BW, Heffelfinger JD. HIV screening in an urban emergency department: comparison of screening using an opt-in versus an opt-out approach. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58(1 Suppl 1):S89–95. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wohl D, Golin C, Rosen D, J M, Bowling M, Green K, White B. Adoption of Opt-out HIV Screening in a State Prison System Had Limited Impact on Detection of Previously Undiagnosed HIV Infection: Results from a Blinded HIV Seroprevalence Study (#1142); Poster session presented at the 19th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; Seattle, Washington. 2012. [Google Scholar]