Abstract

In order to maximize the effectiveness of “Seek, Test, and Treat” strategies for curbing the HIV epidemic, new approaches are needed to increase the uptake of HIV testing services, particularly among high-risk groups. Low HIV testing rates among such groups suggests that current testing services may not align well with the testing preferences of these populations. Female bar workers and male mountain porters have been identified as two important high-risk groups in the Kilimanjaro Region of Tanzania. We used conventional survey methods and a Discrete Choice Experiment (DCE), a preference elicitation method increasingly applied by economists and policy makers to inform health policy and services, to analyze trade-offs made by individuals and quantify preferences for HIV testing services.

Compared to 486 randomly selected community members, 162 female bar workers and 194 male Kilimanjaro porters reported 2 to 3 times as many lifetime sexual partners (p<0.001), but similar numbers of lifetime HIV tests (median 1–2 across all groups). Bivariate descriptive statistics were used to analyze differences in survey responses across groups. For the DCE, participants’ stated choices across 11,178 hypothetical HIV testing scenarios (322 female and 299 male participants × 9 choice tasks × 2 alternatives) were analyzed using gender-specific mixed logit models. Direct assessments and the DCE data demonstrated that barworkers were less likely to prefer home testing and were more concerned about disclosure issues compared with their community counterparts. Male porters preferred testing in venues where antiretroviral therapy was readily available. Both high-risk groups were less averse to traveling longer distances to test compared to their community counterparts.

These results expose systematic differences in HIV testing preferences across high-risk populations compared to their community peers. Tailoring testing options to the preferences of high-risk populations should be evaluated as a means of improving uptake of testing in these populations.

Keywords: HIV testing, Preferences, Discrete choice experiment, HIV diagnosis, Tanzania

Introduction

HIV Counseling and Testing (HCT) is the critical first step to ensure that persons living with HIV (PLWH) access antiretroviral therapy. Antiretroviral therapy not only preserves and restores health among PLWH, but it dramatically decreases HIV transmission at both individual and population levels. In a randomized controlled trial, HIV Prevention Trials Network (HPTN) 052 demonstrated a 96% reduction in HIV transmission among couples in which the HIV-infected partner was started on antiretroviral therapy at higher vs. lower CD4 counts (Cohen et al., 2011), and in the largest population-based prospective cohort study in Africa, individual HIV acquisition risk declined significantly as antiretroviral coverage increased in the surrounding community (Tanser, Barnighausen, Grapsa, Zaidi, & Newell, 2013). Consequently, HIV testing programs designed to be attractive to persons at high-risk for HIV infection (Tanser, de Oliveira, Maheu-Giroux, & Barnighausen, 2014) are pivotal to reducing HIV transmission (Dieffenbach & Fauci, 2009; Fauci & Marston, 2013; Granich, Gilks, Dye, De Cock, & Williams, 2009; Tanser et al., 2014). Yet, current HIV testing rates remain low, including among populations at greatest risk for acquiring and transmitting HIV (Asher, Hahn, Couture, Maher, & Page, 2013; Cawley et al., 2013; Hong et al., 2012; Isingo et al., 2012; O'Donnell et al., 2014; Ostermann, Kumar, Pence, & Whetten, 2007; Pharris et al., 2011; Suthar et al., 2013; Van der Bij, Dukers, Coutinho, & Fennema, 2008; Xu et al., 2011). As policy makers and implementers reach for the aspirational goal of an HIV-free generation, there is urgent need to expand HIV testing, especially among high-risk populations.

In the Kilimanjaro Region of Tanzania, public health officials have identified two such populations: female barworkers and male mountain porters. HIV risk among barworkers in this area has been characterized well, with HIV prevalence estimated at 19 to 26% (Ao, Sam, Masenga, Seage, & Kapiga, 2006; Kapiga et al., 2002). Less is known about the risk characteristics of Kilimanjaro mountain porters. The estimated thousands of porters of Mount Kilimanjaro (Peaty, 2012) are predominantly young males who face volatile income cycles and spend extended time away from home. While no HIV prevalence estimates exist for this population, porters share many characteristics with other high-risk groups, such as long-distance truck drivers (Deane, Parkhurst, & Johnston, 2010; Delany-Moretlwe et al., 2013), fishermen (Kiwanuka et al., 2013; Kwena et al., 2010; Smolak, 2014), miners (Clift et al., 2003; Desmond et al., 2005), and migrant farm workers (Heffron et al., 2011).

In this study, we use a Discrete Choice Experiment (DCE), a survey method commonly used to elicit preferences for goods or services (de Bekker-Grob, Ryan, & Gerard, 2012), to quantify the HIV testing preferences of female barworkers and male Kilimanjaro mountain porters and compare them to randomly selected community members. Grounded in the economic theory of utility maximization, DCEs are increasingly used to understand patient perspectives in order to provide more effective medical care (de Bekker-Grob et al., 2012; Lancsar & Louviere, 2008; Mangham, Hanson, & McPake, 2009). DCEs describe a product or service, in this case HIV testing options, by a number of key characteristics; respondents are presented with a series of choice tasks in which they are asked to select their preferred options. By varying the characteristics of HIV testing options across choice tasks, trade-offs are observed and the value individuals place on each characteristic can be inferred. The results can thus be used to prioritize alternative strategies for better aligning the characteristics of HIV testing options with clients’ preferences for testing.

Methods

The HIV Testing Preferences in Tanzania study (2012–2014) aimed to characterize the testing preferences of at-risk populations in an urban setting in Northern Tanzania. All study activities were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Duke University and Kilimanjaro Christian Medical College, and Tanzania’s National Institute for Medical Research. Participants were provided an incentive of 3,000 Tanzanian Shillings (approximately 1.80 U.S. Dollars). Preferences were assessed using both traditional survey methods and DCE methodology.

DCE development and the characteristics and preferences of 486 randomly selected community residents, ages 18–49, were previously described (Ostermann, Njau, Brown, Muhlbacher, & Thielman, 2014). In short, cluster-randomization and Expanded Programme on Immunization sampling methodology were used to enroll 486 male and female community members, ages 18–49, from randomly selected streets (“mitaa”) in Moshi, Tanzania. Snowball sampling was subsequently used to recruit female barworkers and male mountain porters of the same age range in the same area. Seed participants were recruited from barworkers presenting for a health check-up at a municipal health center and from climbing companies and a porters union.

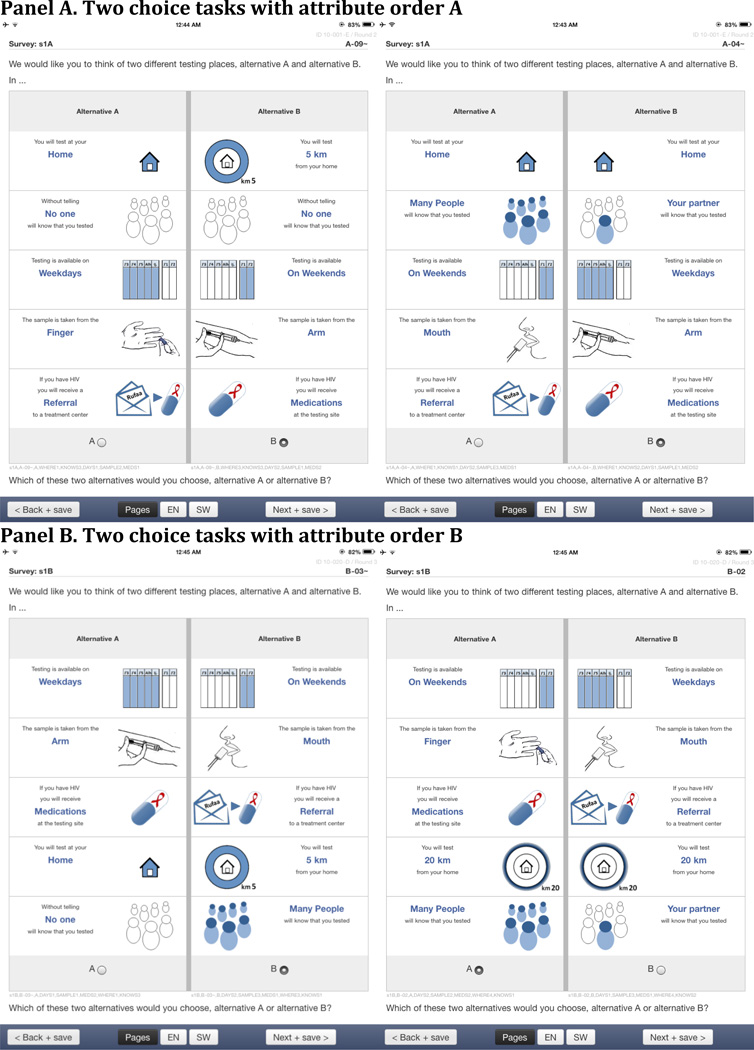

Eligible persons were invited to a research office and verbally consented into the study. A DCE assessed the relative importance to participants of five attributes of HIV testing: distance to testing (home, 1, 5, or 20 kilometers away from home), confidentiality of testing (no-one knows, partner knows, many people know about the test), testing days (weekdays vs. weekend), method for obtaining the sample for testing (blood from finger or arm, oral swab), and availability of HIV medications at the testing site. Qualitative work (Njau et al., 2014) and extensive pre-and pilot tests (Ostermann et al., 2014) identified these attributes as most important for individuals’ testing decisions in this study area. Participants were asked to make 9 consecutive choices between hypothetical HIV testing scenarios (see Appendix 1 for an example) in which the levels of the attributes presented to each participant were systematically varied according to a D-efficient statistical design. A supplemental survey assessed HIV risk, testing history, and preferences for various actual or hypothetical HIV testing options.

APPENDIX.

Examples of choice tasks for the elicitation of HIV testing preferences in Tanzania

Student’s t-tests, Wilcoxon rank sum tests, chi-squared tests, and Fisher’s exact tests assessed the statistical significance of differences between groups of participants. DCE choice data were analyzed in Stata 12.1 (StataCorp, 2011) using gender-specific mixed effects logit models (Hole, 2007) with categorical effects coded explanatory variables (Bech & Gyrd-Hansen, 2005). Parameters were estimated as correlated random coefficients which were assumed to be normally distributed. Interactions terms assessed the significance of differences in DCE preference estimates for barworkers and porters, respectively, relative to the community sample (Ostermann et al., 2014). Wald tests assessed the statistical significance of the interaction terms.

Results

Participation, HIV Risk, and HIV Testing History

In total, 162 female barworkers and 194 male mountain porters participated in this study (Table, Panel A). Due to the study’s focus on the HIV testing preferences of at-risk populations, participants who reported no lifetime sexual partners (7 porters) or reported having previously tested HIV positive (27 barworkers, 3 porters) were excluded from analyses of testing preferences.

Table.

Characteristics and HIV testing preferences of randomly selected community members, female barworkers, and mountain porters

| Females | Males | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Community | Barworkers | Community | Porters | |

| PANEL A. | N | N | N | N |

| Total number of participants | 325 | 162 | 161 | 194 |

| No lifetime sexual partners | 35 | 0 | 45 | 7 |

| Self-reported HIV infection | 3 | 27 | 1 | 3 |

| Number of participants for analysis of preferences | 287 | 135 | 115 | 184 |

| PANEL B. | Mean (standard deviation), N(%), or Median (inter-quartile range)2 | |||

| Demographics | ||||

| Age | 28.6(8.1) | 27.7(5.4) | 24.6(7.2) | 29.2(7.0) *** |

| Married | 193 (59.9%) | 40 (29.6%)*** | 33 (20.6%) | 92 (48.2%) *** |

| Any children | 229 (71.1%) | 85 (63.0%) | 41 (25.8%) | 98 (51.3%) *** |

| HIV risk | ||||

| # of partners, lifetime 1 | 3 (2–4) | 5(3–10)*** | 2(1–3) | 6(4–8) *** |

| # of partners, past 12 months 1 | 1(1–1) | 1(1–2)** | 1(1–1) | 3(2–4) *** |

| Sex for money or gifts, lifetime | 132 (46.0%) | 126 (93.3%)*** | 55 (47.8%) | 162 (84.8%) *** |

| Any alcohol consumption, past 12 months | 85 (26.4%) | 119 (88.1%)*** | 52 (32.5%) | 126 (66.0%) *** |

| Travelled and slept away from home, past 12 months | 179 (55.6%) | 99 (73.3%)*** | 115 (71.9%) | 189 (99.0%) *** |

| Any sexually transmitted disease, past 12 months | 19 (5.9%) | 17 (12.6%)* | 3 (1.9%) | 12 (6.3%) * |

| HIV Testing history | ||||

| # of times tested, lifetime 1 | 1 (0–2) | 1.5 (0–2) | 2 (2–2) | 2 (2–2) |

| Tested in the past 12 months | 122 (37.9%) | 80 (59.3%)*** | 33 (20.6%) | 48 (25.1%) |

| PANEL C. | ||||

| HIV Testing preferences | ||||

| Home (vs. most preferred HIV testing facility) | 221 (68.6%) | 31 (23.0%)*** | 95 (59.4%) | 81 (42.4%) ** |

| Weekend (vs. weekdays) | 131 (40.7%) | 41 (30.4%)* | 100 (62.5%) | 124 (64.9%) |

| Male counselor (vs. female / not important) | 58 (18.0%) | 9 (6.7%)*** | 50 (31.3%) | 47 (24.6%) |

| Doctor or nurse (vs. HIV counselor / not important) | 145 (45.0%) | 46(34.1%)* | 77 (48.1%) | 104 (54.5%) |

| Antiretroviral medications availability at the testing site | 236 (73.3%) | 99 (73.3%) | 103 (64.4%) | 159 (83.2%) *** |

| Venipuncture | 153 (47.5%) | 83 (61.5%)* | 67 (41.9%) | 105 (55.0%) |

| Finger prick | 141 (43.8%) | 45 (33.3%)* | 60 (37.5%) | 56 (29.3%) |

| Oral swab | 28 (8.7%) | 7 (5.2%)* | 33 (20.6%) | 30 (15.7%) |

| Would test using oral test | 251 (78.2%) | 69 (51.1%)*** | 118 (74.2%) | 112 (58.6%) ** |

| Would test using self test | 253 (78.6%) | 59 (43.7%)*** | 126 (78.8%) | 140 (73.3%) |

| Assistance with partner notification if positive | 42 (13.0%) | 29 (21.5%)** | 19 (11.9%) | 34 (17.8%) |

| No partner notification if positive | 11 (3.4%) | 12 (8.9%)** | 10 (6.3%) | 11 (5.8%) |

Median (inter-quartile range)

Significance assessed using Student's t-tests for continuous variables, Wilcoxon rank sum test for count variables, Fisher's exact test for categorical variables with expected cell values <5, and chi-squared tests for other categorical variables

*, **, and *** indicate statistical significance at the 0.05, 0.01, and 0.001 levels, respectively.

As expected, female barworkers and male porters exhibited significantly elevated HIV risk profiles compared with randomly selected community residents (Table, Panel B). Barworkers had nearly twice as many lifetime sexual partners as other female community members (median of 5 vs. 3, p<0.001), and Kilimanjaro porters had three times as many lifetime sexual partners, compared to their male community counterparts (median of 6 vs. 2, p<0.001). The number of sexual partners in the past twelve months also differed significantly, but more so for men than women. Rates of lifetime testing were not significantly different between each high-risk group and their community controls. The rate of HIV testing within the past year was significantly higher among barworkers, who are required to participate in a municipality-mandated health screening program, versus female community members (59.3% vs. 37.9%, p<0.001), but not among porters versus males in the community (25.1% vs. 20.6%, p=0.318).

Direct Assessment of HIV Testing Preferences

Compared with other female community members, barworkers were much less likely to report a preference for home testing (23.0% vs. 68.6%, p < 0.001) over facility based testing (Table, Panel C; a similar but less striking difference was seen among male porters compared with community males (42.4% vs. 59.4%, p=0.002). The table details several additional differences between female barworkers and community members. Fewer barworkers preferred male counselors, oral testing, and self-testing (all, p < 0.001), and more barworkers favored assistance with partner notification or no partner notification if HIV seropositive (each, p<0.01). Among men, more in the porter sample compared to the community sample preferred the availability of medications at the testing site (p<0.001), and similar to barworkers, porters were less likely to prefer an oral test (p<0.01).

Discrete Choice Experiment

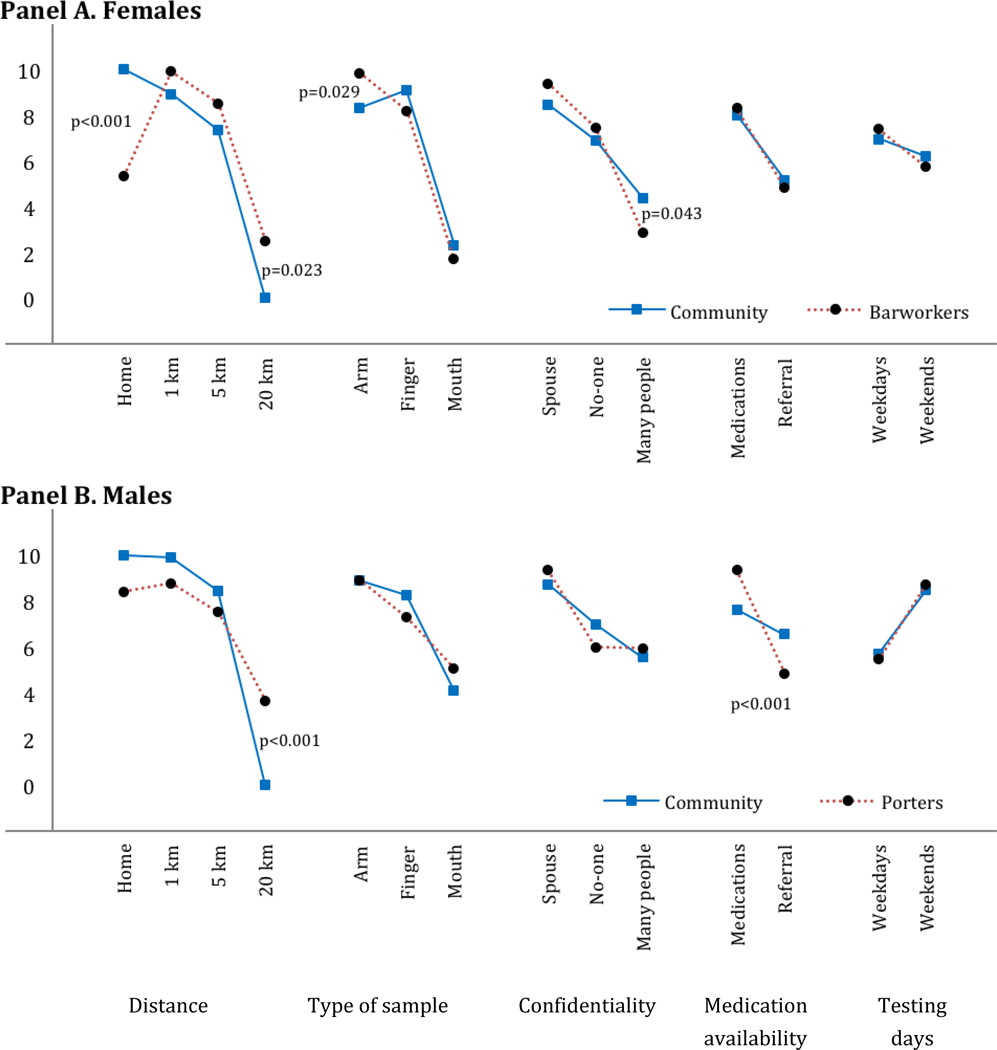

The DCE required participants to make trade-offs between different characteristics of HIV testing options and was used to estimate the relative importance of different test characteristics to participants. The Figure summarizes the results of gender-specific mixed logit models of participants’ stated choices across 11,178 hypothetical HIV testing scenarios (322 female and 299 male participants × 9 choice tasks × 2 alternatives; see methods and the detailed description of the experimental design and survey administration in the companion paper (Ostermann et al., 2014)). The Y-axis represents an estimate of participants’ relative preference for a test with a given attribute-level combination (e.g., “distance - 1 km from home”), holding all other factors constant. A larger value indicates a greater likelihood of choosing a test with the specific feature. With the exception of HIV medication availability for male community members, and weekend vs. weekday testing for female community members, all attributes were significantly associated with HIV testing preference in all sub-populations (not shown). The rank-ordering of attributes describes their relative importance to participants. Of the features evaluated in our survey, distance was ranked as most important, followed by the type of sample. Weekday vs. weekend testing was ranked least important. Comparisons of the relative valuations of different attribute levels across attributes allows for estimates of their marginal rate of substitution. For example, the difference between testing at home vs. 1 km away from home was more important to barworkers than the difference between venipuncture vs. finger pricks. Finally, analyses of the interaction terms confirmed significantly different preferences between groups. Community members most preferred testing at home and least preferred testing out of town. Comparing each high-risk group to their gender-matched community counterparts, barworkers and porters were more willing to traveling out of town for testing (p=0.023 and p=0.001, respectively). Barworkers were more reluctant to test at home (p<0.001) and had a stronger preference for venipuncture (p=0.029) than other female community members. All groups most preferred their spouses knowing that they tested and least preferred many people knowing that they tested. Barworkers were more averse than other community members to many people knowing about their HIV test (p=0.043). Porters placed more value than other males on the availability of HIV medications at the testing site (p<0.001).

Figure 1. Scaled estimates of HIV testing preferences from a Discrete Choice Experiment with randomly selected community members and two high-risk populations.

Description: Differences in HIV testing preferences between randomly selected female community members and barworkers (Panel A) and male community members and mountain porters (Panel B). Models included effects-coded correlated random main effects and fixed interactions between attribute levels and participants’ membership in the respective high-risk group. p-values indicate statistically significant differences between the respective groups, as measured by the interaction terms. Coefficients were re-scaled to range from 0 to 10.

Discussion

Using direct assessments and DCE methods, this study is the first to demonstrate systematic differences in HIV testing preferences between high risk groups and randomly selected community members in sub-Saharan Africa. Both methods showed that barworkers were significantly less likely to prefer home testing and were more concerned about disclosure issues, compared with other women in the community. Similarly, each method indicated that porters preferred testing in venues where antiretroviral therapy was readily available. In addition, DCEs characterized the relative importance of different testing characteristics for each subgroup, and revealed that both high-risk groups were less averse to traveling longer distances to be tested and that barworkers were less averse to venipuncture relative to finger pricks. Taken together, these results expose clear differences in how high-risk populations prefer to test compared to others in the community and underscore the need to better align HIV testing services with the preferences of these populations.

Appropriately, in settings such as most of sub-Saharan Africa, where the HIV epidemic is generalized, HIV testing should be broadly accessible to the general population. However, supplemental efforts that tailor HIV prevention strategies for high risk groups according to their preferences may be more effective per intervention dollar spent (Aral & Cates, 2013; Gouws, Cuchi, & International Collaboration on Estimating, 2012; HIV/AIDS, 2011; Pruss-Ustun et al., 2013; Tanser et al., 2014). Across both low- and high- prevalence regions, mathematical models predict that such focused interventions could reduce HIV transmission in the broader community (Mishra, Steen, Gerbase, Lo, & Boily, 2012). Yet, relatively few interventions are being devised to specifically target high-risk populations in sub-Saharan Africa.

Basic marketing principles suggest that aligning the characteristics of a product or service to consumer preferences will lead to increased utilization. Discrete choice modeling, developed by economists and applied widely in marketing research, has been used increasingly to guide policies and interventions towards patient-centered and client-centered outcomes (Bridges et al., 2011). The application of this methodology for tailoring HIV testing among high-risk populations in Africa is unique. To effectively reach high-risk groups, many of whom are prone to stigma and discrimination (e.g. sex workers (Baral et al., 2012) and men who have sex with men in Africa (Smith, Tapsoba, Peshu, Sanders, & Jaffe)), operate at the margins of society (Baral et al., 2012; Smith et al.) (e.g. fishing communities in Uganda (Kiwanuka et al., 2014)), or are otherwise difficult to reach because of the nature of their work (such as mountain porters and truck drivers), the application of robust methods that explore the utility of individual attributes of testing services across different populations holds particular promise.

We note several limitations. First, we focused on only two specific high-risk groups in a single urban setting. While they share characteristics with other high-risk populations, such as commercial sex workers, truck drivers, and seasonal or migrant workers, the testing preferences for these groups remain unknown. The generalizability of these group preferences to other areas with decreased access to HIV testing services is also unknown. Second, owing to the snowball sampling approach, the representativeness of the high-risk samples, and thus the extent to which selection biases influenced the preference estimates, cannot be assessed. Preference assessments to inform the development of actual, preference-based testing options for these high-risk populations should use other (e.g. consecutive or random sampling) methods that minimize selection biases. Third, the relatively high rates of HIV testing among female barworkers may be the result of their enrollment while presenting for a health check-up or of many years of sexually transmitted infection research in the study area (Ao et al., 2006; Kapiga et al., 2002; Kiwelu et al., 2012). Further research should elicit the testing preferences of other high-risk groups with less exposure to HIV testing, and should assess the influence of mandated health check-ups on HIV testing decisions.

Despite these limitations, the findings underscore the utility of applying stated preference research methods for developing client-centered HIV-testing strategies, and form a rational basis for piloting novel testing approaches among high-risk populations in the Kilimanjaro Region. For example, specific interventions might include developing or promoting venue-based testing centers that are linked to existing care and treatment centers where antiretroviral medications are readily available, and the provision of informational materials that highlight blood sampling through venipuncture, the confidential nature of the encounter, and the availability of assistance with partner notification. The results of DCE-based preference assessments can help prioritize such interventions with respect to their expected effects on the testing decisions of high-risk individuals.

Conclusion

HIV testing preferences of two high risk groups differ from those of the community. HIV testing options tailored to the preferences of high-risk populations may be effective and cost-effective means for increasing rates of testing among high-risk populations.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Max Masnick and Cassava Labs, LLC for the development of the iPad-based software for the collection of DCE data; Andrew Weinhold for assistance with sampling; Martha Masaki, Elizabeth Mbuya, Beatrice Mandao, and Honoratha Israel for study implementation, data collection and entry; Elizabeth Reddy and Bernard Agala for assistance with qualitative research; and the Kilimanjaro Clinical Research Institute for administrative support.

Funding

This publication was made possible by Grant Number R21 MH096631 from the National Institute of Mental Health, and supported by the Duke University Center for AIDS Research (CFAR), an NIH funded program (P30 AI064518). The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Mental Health or the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Ao TT, Sam NE, Masenga EJ, Seage GR, 3rd, Kapiga SH. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 among bar and hotel workers in northern Tanzania: the role of alcohol, sexual behavior, and herpes simplex virus type 2. Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33(3):163–169. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000187204.57006.b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aral SO, Cates W., Jr Coverage, context and targeted prevention: optimising our impact. Sex Transm Infect. 2013;89(4):336–340. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2012-050707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asher AK, Hahn JA, Couture MC, Maher K, Page K. people who inject drugs, HIV risk, and HIV testing uptake in sub-Saharan Africa. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2013;24(6):e35–e44. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baral S, Beyrer C, Muessig K, Poteat T, Wirtz AL, Decker MR, Kerrigan D. Burden of HIV among female sex workers in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12(7):538–549. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bech M, Gyrd-Hansen D. Effects coding in discrete choice experiments. Health Economics. 2005;14:1079–1083. doi: 10.1002/hec.984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridges JF, Hauber AB, Marshall D, Lloyd A, Prosser LA, Regier DA, Mauskopf J. Conjoint analysis applications in health--a checklist: a report of the ISPOR Good Research Practices for Conjoint Analysis Task Force. Value Health. 2011;14(4):403–413. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2010.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cawley C, Wringe A, Isingo R, Mtenga B, Clark B, Marston M, Zaba B. Low rates of repeat HIV testing despite increased availability of antiretroviral therapy in rural Tanzania: findings from 2003–2010. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e62212. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clift S, Anemona A, Watson-Jones D, Kanga Z, Ndeki L, Changalucha J, Ross DA. Variations of HIV and STI prevalences within communities neighbouring new goldmines in Tanzania: importance for intervention design. Sex Transm Infect. 2003;79(4):307–312. doi: 10.1136/sti.79.4.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour MC, Kumarasamy N, Team HS. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(6):493–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bekker-Grob EW, Ryan M, Gerard K. Discrete choice experiments in health economics: a review of the literature. Health Econ. 2012;21(2):145–172. doi: 10.1002/hec.1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deane KD, Parkhurst JO, Johnston D. Linking migration, mobility and HIV. Trop Med Int Health. 2010;15(12):1458–1463. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02647.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delany-Moretlwe S, Bello B, Kinross P, Oliff M, Chersich M, Kleinschmidt I, Rees H. HIV Prevalence and risk in long-distance truck drivers in South Africa: a national cross-sectional survey. Int J STD AIDS. 2013 doi: 10.1177/0956462413512803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desmond N, Allen CF, Clift S, Justine B, Mzugu J, Plummer ML, Ross DA. A typology of groups at risk of HIV/STI in a gold mining town in north-western Tanzania. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60(8):1739–1749. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dieffenbach CW, Fauci AS. Universal voluntary testing and treatment for prevention of HIV transmission. JAMA. 2009;301(22):2380–2382. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fauci AS, Marston HD. Achieving an AIDS-free world: science and implementation. Lancet. 2013;382(9903):1461–1462. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62042-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouws E, Cuchi P, International Collaboration on Estimating HIVIbMoT. Focusing the HIV response through estimating the major modes of HIV transmission: a multi-country analysis. Sex Transm Infect. 2012;88(Suppl 2):i76–i85. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2012-050719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granich RM, Gilks CF, Dye C, De Cock KM, Williams BG. Universal voluntary HIV testing with immediate antiretroviral therapy as a strategy for elimination of HIV transmission: a mathematical model. Lancet. 2009;373(9657):48–57. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61697-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heffron R, Chao A, Mwinga A, Sinyangwe S, Sinyama A, Ginwalla R, Bulterys M. High prevalent and incident HIV-1 and herpes simplex virus 2 infection among male migrant and non-migrant sugar farm workers in Zambia. Sex Transm Infect. 2011;87(4):283–288. doi: 10.1136/sti.2010.045617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HIV/AIDS JUNPo. How to get to zero: Faster. Smarter. Better. World AIDS Day Report 2011. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- Hole AR. Fitting mixed logit models by using maximum simulated likelihood. The Stata Journal. 2007;7(3):388–401. [Google Scholar]

- Hong Y, Zhang C, Li X, Fang X, Lin X, Zhou Y, Liu W. HIV testing behaviors among female sex workers in Southwest China. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(1):44–52. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9960-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isingo R, Wringe A, Todd J, Urassa M, Mbata D, Maiseli G, Zaba B. Trends in the uptake of voluntary counselling and testing for HIV in rural Tanzania in the context of the scale up of antiretroviral therapy. Trop Med Int Health. 2012;17(8):e15–e25. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2011.02877.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapiga SH, Sam NE, Shao JF, Renjifo B, Masenga EJ, Kiwelu IE, Essex M. HIV-1 epidemic among female bar and hotel workers in northern Tanzania: risk factors and opportunities for prevention. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;29(4):409–417. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200204010-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiwanuka N, Ssetaala A, Mpendo J, Wambuzi M, Nanvubya A, Sigirenda S, Sewankambo NK. High HIV-1 prevalence, risk behaviours, and willingness to participate in HIV vaccine trials in fishing communities on Lake Victoria, Uganda. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16(1):18621. doi: 10.7448/IAS.16.1.18621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiwanuka N, Ssetaala A, Nalutaaya A, Mpendo J, Wambuzi M, Nanvubya A, Sewankambo NK. High Incidence of HIV-1 Infection in a General Population of Fishing Communities around Lake Victoria, Uganda. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(5):e94932. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiwelu IE, Novitsky V, Margolin L, Baca J, Manongi R, Sam N, Essex M. HIV-1 subtypes and recombinants in Northern Tanzania: distribution of viral quasispecies. PLoS One. 2012;7(10):e47605. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwena ZA, Bukusi EA, Ng'ayo MO, Buffardi AL, Nguti R, Richardson B, Holmes K. Prevalence and risk factors for sexually transmitted infections in a high-risk occupational group: the case of fishermen along Lake Victoria in Kisumu, Kenya. Int J STD AIDS. 2010;21(10):708–713. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2010.010160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancsar E, Louviere J. Conducting discrete choice experiments to inform healthcare decision making: a user's guide. Pharmacoeconomics. 2008;26(8):661–677. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200826080-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangham LJ, Hanson K, McPake B. How to do (or not to do) ... Designing a discrete choice experiment for application in a low-income country. Health Policy Plan. 2009;24(2):151–158. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czn047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra S, Steen R, Gerbase A, Lo YR, Boily MC. Impact of high-risk sex and focused interventions in heterosexual HIV epidemics: a systematic review of mathematical models. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(11):e50691. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Njau B, Ostermann J, Brown D, Muhlbacher A, Reddy E, Thielman N. HIV testing preferences in Tanzania: a qualitative exploration of the importance of confidentiality, accessibility, and quality of service. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:838. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Donnell K, Yao J, Ostermann J, Thielman N, Reddy E, Whetten R, Whetten K. Low rates of child testing for HIV persist in a high-risk area of East Africa. AIDS Care. 2014;26(3):326–331. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2013.819405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostermann J, Kumar V, Pence BW, Whetten K. Trends in HIV testing and differences between planned and actual testing in the United States, 2000–2005. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(19):2128–2135. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.19.2128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostermann J, Njau B, Brown DS, Muhlbacher A, Thielman N. Heterogeneous HIV Testing Preferences in an Urban Setting in Tanzania: Results from a Discrete Choice Experiment. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e92100. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peaty D. Kilimanjaro Tourism and What It Means for Local Porters and for the Local Enviroment. Journal of Ritsumeikan Social Sciences and Humanities. 2012;4 [Google Scholar]

- Pharris A, Nguyen TK, Tishelman C, Brugha R, Nguyen PH, Thorson A. Expanding HIV testing efforts in concentrated epidemic settings: a population-based survey from rural Vietnam. PLoS One. 2011;6(1):e16017. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruss-Ustun A, Wolf J, Driscoll T, Degenhardt L, Neira M, Calleja JM. HIV due to female sex work: regional and global estimates. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(5):e63476. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AD, Tapsoba P, Peshu N, Sanders EJ, Jaffe HW. Men who have sex with men and HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa. The Lancet. 374(9687):416–422. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61118-1. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61118-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smolak A. A meta-analysis and systematic review of HIV risk behavior among fishermen. AIDS Care. 2014;26(3):282–291. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2013.824541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 12. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Suthar AB, Ford N, Bachanas PJ, Wong VJ, Rajan JS, Saltzman AK, Baggaley RC. Towards universal voluntary HIV testing and counselling: a systematic review and meta-analysis of community-based approaches. PLoS Med. 2013;10(8):e1001496. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanser F, Barnighausen T, Grapsa E, Zaidi J, Newell ML. High coverage of ART associated with decline in risk of HIV acquisition in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Science. 2013;339(6122):966–971. doi: 10.1126/science.1228160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanser F, de Oliveira T, Maheu-Giroux M, Barnighausen T. Concentrated HIV subepidemics in generalized epidemic settings. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2014;9(2):115–125. doi: 10.1097/COH.0000000000000034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Bij AK, Dukers NH, Coutinho RA, Fennema HS. Low HIV-testing rates and awareness of HIV infection among high-risk heterosexual STI clinic attendees in The Netherlands. Eur J Public Health. 2008;18(4):376–379. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckm120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Brown K, Ding G, Wang H, Zhang G, Reilly K, Wang N. Factors associated with HIV testing history and HIV-test result follow-up among female sex workers in two cities in Yunnan, China. Sex Transm Dis. 2011;38(2):89–95. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181f0bc5e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]