Abstract

Backround:

The study is focused on increased risk of dental plaque accumulation among the children undergoing orthodontic treatment in consideration of individual hygiene and dietary habits.

Materials and Methods:

The study was conducted among 91 children aged 7-14 including 47 girls and 44 boys. The main objectives of the study were: API index, plaque pH, DMF index, proper hygiene and dietary habits. Statistical analysis was provided in Microsoft Office Exel spreadsheet and STATISTICA statistical software.

Results:

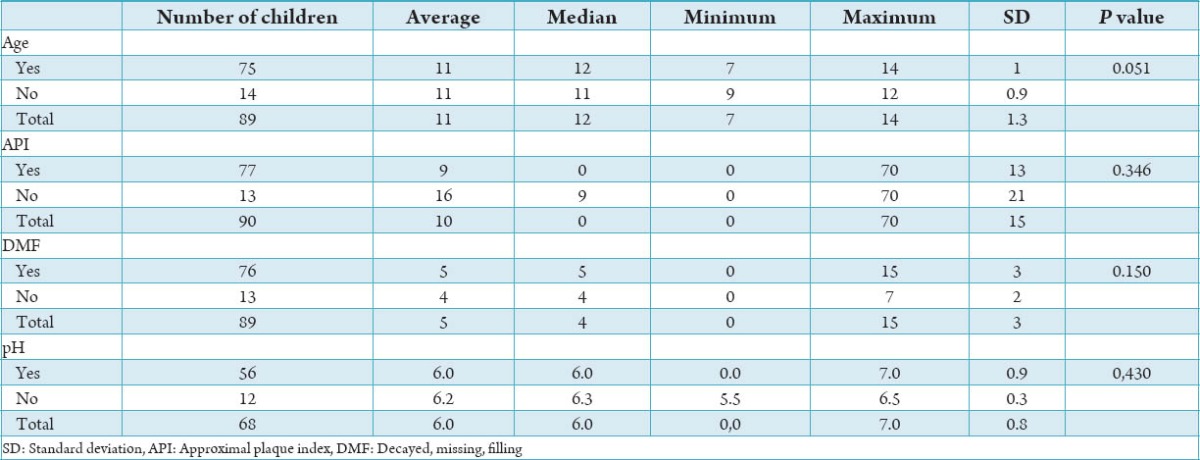

The average API index among the children wearing removable appliance was 9 (SD = 13), and among children without appliances was 16 (SD = 21). DMF index for patients using appliances was 5 (SD = 3) and for those without appliances was 4 (SD = 2). The average plaque pH was 6 for children with appliances (SD = 0.9) and 6.2 without ones (SD = 0.3).

Conclusion:

In patients in whom there is a higher risk of dental plaque accumulating, correct oral hygiene supported with regular visits to the dentist is one of the best ways to control dental caries. In the fight against caries the most effective and only approach is to promote awareness of the problem, foster proper hygiene and nutritional habits, as well as educate children from a very young age in how to maintain proper oral hygiene.

Keywords: Caries risk, children, hygiene and dietary habits, oral hygiene, orthodontic treatment

Introduction

Oral hygiene can vary in children within the same age group and depends on many factors, one of the most important of which are the hygiene habits of adults and the steps they take to pass on these habits to those in their care. Being aware of the need to take care of oral health is reflected in the frequency with which one brushes one’s teeth, uses toothpaste, mouthwash and dental floss. Another factor, that should not be overlooked, is the influence of advertising on the choice and use of oral hygiene products, as well as in shaping dietary habits, including the consumption of sweets and soft drinks.1-3 Over the last few years, many researchers have looked at the problem of dental caries in children and the relationship between the disease and oral hygiene. They have stressed the importance of brushing teeth carefully 1-2 times a day so as to prevent carious lesions occurring.

Even frequent consumption of sweets and sweetened beverages has no significant impact on the occurrence of caries in child patients when regular, and proper oral hygiene is observed. A study conducted by the Medical University of Lublin shows that parents frequently do not attach much importance to the oral hygiene of their children and only take them to the dentist for the first time when their son or daughter is already complaining of toothache. It has also been pointed out that in the majority of cases children do not brush their teeth after meals, eating sweets or drinking beverages that cause dental caries.1

The most common areas for dental caries to develop in are those in which it is difficult to maintain hygiene. Such places include areas in which food debris and dental deposits can easily build up, even when the patient has proper occlusion. Correct oral hygiene is impeded by pathological changes occurring in the mucous membrane, hypertrophy of the interdental papilla, the appearance of pathological pockets, cavities, badly shaped fillings and malocclusions as well as wearing orthodontic appliances.2,4

Objective of the study

The objectives of the study were as follows:

Analyze selected hygiene parameters: (Approximal plaque index [API], Plaque pH),

Assess the status of patients’ permanent teeth (decayed, missing, filling [DMF]),

Assess whether patients observe proper hygiene habits,

Assess their dietary habits,

Attempt to identify a relationship between the type of present dental plaque and an increase in the risk of dental caries.

Study Materials and Methods

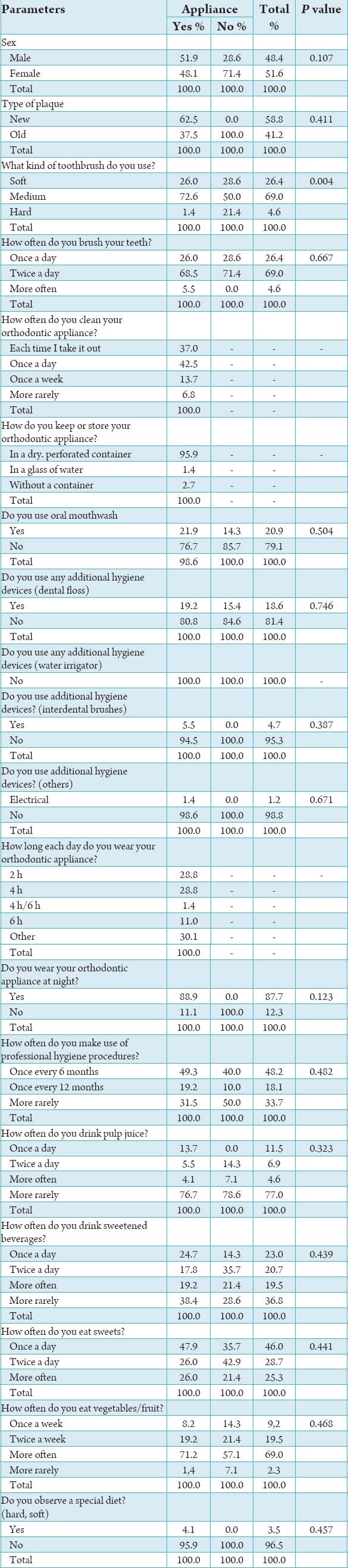

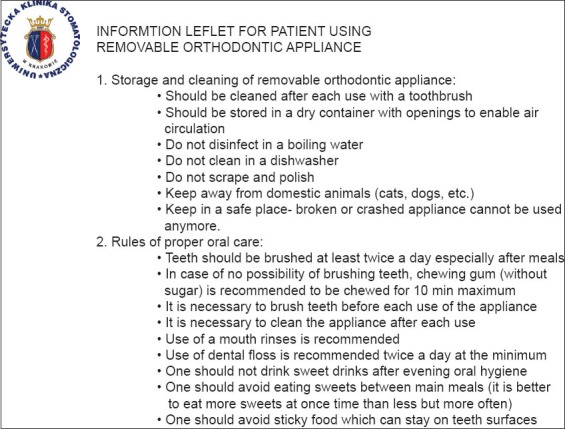

The study was conducted among children undergoing or at the beginning of orthodontic treatment in one of the Krakow area clinics. The study encompassed 91 children aged 7-14, 77 of whom used removable orthodontic appliances and 14 of whom had only just begun treatment. The study group comprised of 47 girls and 44 boys. The study consisted of two parts: a survey with questions on the children’s everyday hygiene and dietary habits (Table 1) as well as an intraoral examination that involved disclosing the children’s dental plaque. The questionnaire was prepared on the basis of a joint study edited by Prof. Dr. Hab. M. Wierzbicka called “Diagnosing Caries Risk and Selecting a Standard of Prevention.” After being examined each child received a list of instructions on how to ensure proper daily oral hygiene, especially during the course of orthodontic treatment (Figure 1). After receiving the appropriate instructions, the child was then sent home and asked to return for a follow-up visit approximately 3 months later.

Table 1.

Questionnaire results.

Figure 1.

Information leaflet handed to patients following clinical examination.

The dental plaque was disclosed with a Plaque Indicator Kit (GC Europe), which included a gel (Plaque Disclosing Gel) used for intraoral dyeing of dental deposits and a reagent for measuring the pH of plaque (Plaque Indicator Solution). Both preparations disclosed the dental plaque in a distinctive way. This made it possible to carry out a simple analysis of its cariogenic potential and provide a basis for instructing the patient in what measures need to be taken. If the plaque turns pink or red in color this indicates the presence of fresh deposits, while a blue or violet hue indicates the deposits are at least 48 h old (Figures 2 and 3). The Plaque Indicator Solution measures pH within a range of between 7.2 and 5.0. The color green represents a pH of 7.2 (neutral), while colors ranging between yellow and orange represent a pH of 6.0-6.6. Pink to red gives a pH of 5.0-5.8. A color range between yellow and red indicates that the plaque has a high cariogenic potential, and on this basis the patient can be re-educated and instructed in what preventative measures to take.

Figure 2.

After disclosing of mature dental plaque, 10 years old boy.

Figure 3.

After disclosing of immature dental plaque, 9 years old boy.

In addition to disclosing dental deposits the state of the patient’s oral hygiene (API index, according to Lange) and the presence of caries (DMF index)5,6 were also assessed during the examination. The presence of dental plaque was examined in all interdental spaces on the vestibular side of the oral cavity while the DMF index was only applied to permanent teeth.

With the aim of determining oral hygiene according to the API index the following breakdown was used:

100-70% incorrect oral hygiene,

69-40% average oral hygiene

39-25% relatively good oral hygiene,

<25% optimal hygiene

Statistical analysis of the data obtained from the intraoral examination and questionnaire were made with a Microsoft Office Excel spreadsheet and STATISTICA statistical software. The Chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test (P ≤ 0.05) were employed to determine correlations between the studied parameters.

Study Results

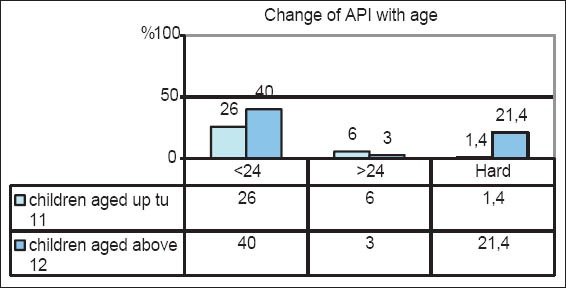

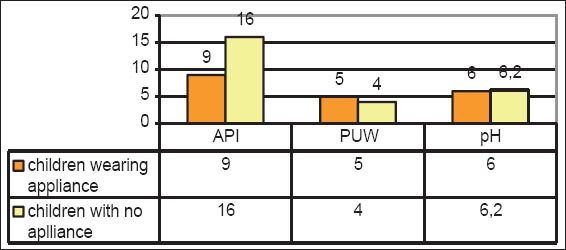

The average API index for children wearing removable orthodontic appliances was 9 (min = 0, max = 70, median = 0, standard deviation [SD] = 13, P = 0.346) while in children not wearing such appliances the index was 16 (min = 0, max = 70, median = 9, SD = 21, P = 0.346). The API index was marginally lower in older children (Graph 1). The upper age limit was set at 11, for it is precisely in the children who were turning 12 that the greatest improvement in oral hygiene was observed, including a better API index or an increase in plaque pH. This study did not show any statistically significant differences in oral hygiene between children wearing removable appliances and those not wearing such appliances (Graph 2 and Table 2).

Graph 1.

Correlation between approximal plaque index and age of patient.

Graph 2.

Studied indicators in children wearing removable orthodontic appliances and children not wearing such appliances (mean values).

Table 2.

Assessment results for certain oral hygiene indices.

The average DMF index for patients using such appliances was 5 (min = 0, max = 15, median = 5, SD = 3, P = 0.150), while for those not wearing such appliances the score was 4 (min = 0, max = 7, median = 4, SD = 2, P = 0.150) (Graph 2).

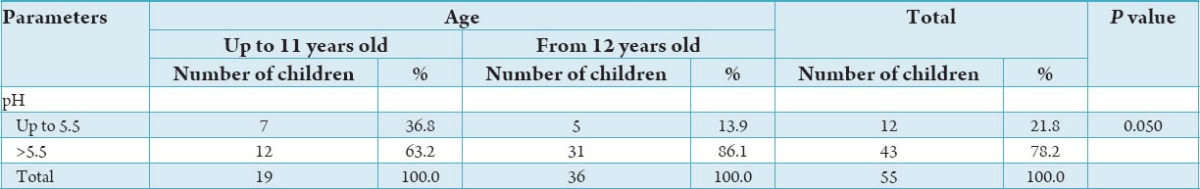

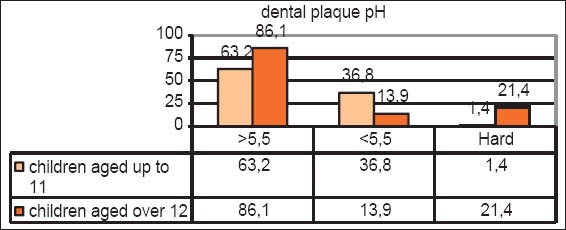

The average dental plaque pH in children wearing orthodontic appliances was 6 (min = 0; max = 7; median = 6; SD = 0.9) and for the other children it was 6.2 (min = 5.5; max = 6.5; median = 6.3; SD = 0.3). The wearing of an orthodontic appliance did not have too great an influence on changes in plaque pH while a certain correlation was observed between pH and the age of the patients in the study. A higher pH value, and as a consequence a lower cariogenic potential, was observed in older children. A plaque pH of over 5.5 was noted in 63.2% of children up to 11 years old while in children above the age of 12 it was noted in as many as 86.1% (P = 0.050) (Table 3 and Graph 3).

Table 3.

Correlation between dental plaque pH and age of child.

Graph 3.

Correlation between dental plaque pH and age of child.

The questionnaire showed that a clear majority of young patients use a toothbrush of soft or medium hardness (95.4%) and brush their teeth two times a day (69%). Children wearing orthodontic appliances used a hard toothbrush more often (P = 004). The respondents’ answers regarding their use of additional hygiene devices offered little cause for optimism. Only 19% of the respondents used dental floss. On a far more positive note, almost 80% of children said they rinse their mouths with oral mouthwashes. Forty-eight percent of the children declared that they underwent hygiene procedures such as air-abrasion or scaling once every 6 months. The others do so once a year (18%) or more rarely (34%).

More than 78% of the respondents said that they eat fruit or vegetables at least twice a week while around 71% declared that they consumed sweets once a day or more rarely. Almost 89% of the respondents said that they drink pulp juices once a day or more rarely, whereas 60% of the children declared that they consumed sweetened beverages at a similar rate (Table 1).

Follow-up visits were planned after 3 months, and around 10% of the children in the study actually appeared for the visits.

Discussion

Just as other researchers have noted, we observed in our study a correlation between the sex of the respondent and the DMF index. Similar to numerous other studies our research showed that boys had a higher DMF index than girls.1,2 If the relationship between oral hygiene and the sex of a child may not appear to be quite comprehensible, the improvement in this index as the child gets older is easier to understand. The study revealed that a major turning point, when it comes to improved oral hygiene, occurs as the child gets older, and to be more exact when the child is around 11 years of age. The pH of dental plaque clearly increases in older children, as a consequence of which its cariogenic potential decreases. The children’s API index also gets lower, which suggests an improvement in oral hygiene. The above observations may be proof that as the patient gets older his/her health awareness is also greater. Unfortunately, a fairly late change in hygiene habits in relation to the transition period from deciduous to permanent dentition and the frequency of cavities in deciduous teeth does not always lead to expected results. One of the most important factors in dealing with dental caries is he need to adopt proper hygiene habits as early as possible, which can minimize the development of the disease. Lack of the systemic approach combined with limited social understanding of the problem is clearly not helping improve children’s awareness of the need to take care of their oral hygiene.

Numerous studies show that besides individual hygiene habits a child’s oral hygiene also depends on a number of other factors over which the young patient has no influence.7 The material status of a child’s family, the age of the mother and the education of the parents can have a major impact on the quality and frequency of hygiene procedures practiced by children. It has been observed that girls have far better teeth and healthier periodontium than boys.8 Similarly, better educated people pay far more attention to their oral hygiene. Pawka et al. report that children of mothers aged over 35 have better oral hygiene than the children of younger mothers. Moreover, a positive relationship was observed between the oral hygiene of children and the professional status of their mothers, although no such relationship is evident in the case of the father.1,8,9 The limited awareness of parents with regard to caries prevention and treatment does not bode well in the future fight against dental caries. Many authors have addressed the issue of ensuring parents are better educated in this area and called for increased vigilance from doctors and other specialists, in particular pediatricians. This is because they are first and often for a long time the only doctors who can pay attention to the oral hygiene of the child patient as well refer them to a dental surgery.10,11

The objective of the present study was to correctly identify and analyze daily habits and re-educate the patient. After the children had received a helpful list of hygiene instructions, they were invited to return for follow-up visits with their parents. The aim of the follow-up was not only to assess the effectiveness of our efforts but also to check how conscientiously patients, who took part in and consented to the survey, had followed our instructions. Unfortunately, only around 10% of the respondents appeared for the follow-up visits. This proved that despite the possibility of having free-of-charge check-ups and health education patients are failing to observe the principles of the program. The failure of parents to keep to dental visits and also perhaps insufficient awareness of the importance of proper caries prevention are two factors that can negatively affect the oral hygiene of their children. In addition, the closing down of dental surgeries in schools, and reduced working hours for nurses in schools and nursery schools have also not helped foster healthier attitudes and behavior, including when it comes to dental care.

Conclusions

There is a clear improvement in children’s oral hygiene when they reach 11 years of age.

When practicing hygiene procedures very young children should be under parental supervision.

A relationship may exist between the failure to attend follow-up visits and a lack of desire among parents to improve the oral hygiene of their children.

Parents need to be properly educated, and their attention drawn to the need to practice caries prevention.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None

Source of Support: Nil

References

- 1.Topolska J, Bałanda W, Malicka M, Rudnicka- Siwek K, Pels E, Borowksa M. Analysis of parents`health educaton and nutritional habits in relations to the state of the deciduous dentition of their children. Dent Forum. 2006;1:37–41. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Szyszka-Sommerfeld L, Buczkowska-Radlińska J. Influence of tooth crowding on the prevalence of dental caries. A literature review. Ann Acad Med Stetin. 2010;56(2):85–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wojtko E. Oral hygiene influence on dental caries experience of permanent teeth in children during dentition time. Prz Stomatol Wieku Rozw. 1996;2-3:51–4. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mikołajczyk M. Influence of teeth crowding on possibility hygien maintance in oral cavity in children. Prz Stomatol Wieku Rozw. 1998;4:22–5. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wdowiak L, Szymańska J, Mielnik-Błaszczak M. Oral cavity condition monitoring. Dent Caries indic Zdr Publ. 2004;114:99–103. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Postek-Stefańska L, Skowronek A. The usefulness of some tests for evaluation of caries risk in children. Twój Prz Stomatol. 2005;4:13–6. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van den Branden S, Van den Broucke S, Leroy R, Declerck D, Hoppenbrouwers K. Measuring determinants of oral health behavior in parents of preschool children. Community Dent Health. 2013;30:19–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pawka B, Wdowiak L, Szymańska J. Dental condition of hygienic routines in 12-year-old children in urban and rural. Zdr Publ. 2007;2:171–4. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khatri SG, Acharya S, Srinivasan SR. Mothers`sense of coherence and oral health related quality of life of preschool children in Udupi Taluk. Community Dent Health. 2014;31:32–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hajto-Bryk J. Rozprawa Doktorska. Kraków: Uniwersytet Jagielloński; 2012. Dentition of pre-school children and adolescence in malopolska region- state for 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frank J, Hayes MJ, Taylor JA. The provision of dietary advice by dental practitioners: A review of the literature. Community Dent Health. 2014;31:9–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]