Abstract

Triple-negative (ER-, HER2-, PR-) breast cancer (TNBC) is an aggressive disease with a poor prognosis with no available molecularly targeted therapy. Silencing of micRoRNA-145 (miR-145) may be a defining marker of TNBC based on molecular profiling and deep sequencing. Therefore, the molecular mechanism behind miR-145 down-regulation in TNBC was examined. Overexpression of the long non-coding RNA, lincRNA-RoR, functions as a competitive endogenous RNA sponge in TNBC. Interestingly, lincRNA-RoR is dramatically upregulated in TNBC and in metastatic disease and knockdown restores miR-145 expression. Previous reports suggest that miR-145 has growth suppressive activity in some breast cancers; however, the current data in TNBC indicates that miR-145 does not impact proliferation or apoptosis but instead, miR-145 regulates tumor cell invasion. Investigation of miR-145 regulated pathways involved in tumor invasion revealed a novel target, the small GTPase ADP-ribosylation factor 6 (Arf6). Subsequent analysis demonstrated that ARF6, a known regulator of breast tumor cell invasion, is dramatically upregulated in TNBC and in breast tumor metastasis. Mechanistically, ARF6 regulates E-cadherin localization and impacts cell-cell adhesion. These results reveal a lincRNA-RoR/miR-145/ARF6 pathway that regulates invasion in TNBCs.

Implications

The lincRNA-RoR/miR-145/ARF6 pathway is critical to TNBC metastasis and could serve as biomarkers or therapeutic targets for improving survival.

Keywords: competitive endogenous RNA, long non-coding RNA, micRoRNA, invasion, metastasis, breast cancer

Introduction

Breast cancer is the second leading cause of cancer deaths among women(1). Obstacles to improving clinical outcomes include better understanding of disease recurrence, overcoming drug resistance, and preventing metastasis. Improvements in breast cancer clinical treatment have come from rationally designed molecularly targeted therapeutics. For patients with estrogen-receptor positive disease, antiestrogen treatments including selective estrogen receptor (ER) modulators and aromatase inhibitors have been a major success story. Furthermore, treatment of HER2/neu overexpressing breast cancers with the recombinant humanized anti-HER2 monoclonal antibody trastuzumab has dramatically improved prognosis for these patients. For patients with triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), those lacking ER, PR, and HER2 expression, there are currently no available molecularly targeted therapeutics(2). TNBC accounts for around 20% of cases of breast cancer in the US where it is frequently observed in younger women and African American women(3). TNBC is frequently aggressive and fast growing but it does respond to chemotherapy. Nevertheless, understanding the molecular mechanisms driving TNBC will allow rational target selection and new drug development.

Dysregulation of micRoRNAs (miRs) is emerging as a major contributor to tumorigenesis in breast cancers. In a recent study, Volinia et al. examined breast tumor deep sequencing data in an attempt to identify miRs linked with breast tumor invasiveness(4). When comparing miRdsyregulation in different molecular subtypes they found that miR-145 was among the most significantly repressed miRs in TNBC. miR-145 is a reported growth suppressor downregulated in many cancer including lung(5), prostate(6), breast(7), colon(8), and bladder cancers(9).

Recently, a role for miR-145 in the regulation of embryonic stem cell (ESC) renewal was reported(10). Levels of miR-145 in ESCs remain low, while upon forced differentiation, miR-145 levels increase dramatically, whereas levels of pluripotency factors OCT4, SOX2, and KLF4 decrease. OCT4, SOX2, and KLF4 were all confirmed to be directtargets of miR-145 in ES cells and embryoid bodies. In addition to regulating ESC renewal, miR-145 has also been shown to be a regulator of adult stem cell renewal. miR-145 was found to regulate mesenchymal stem cell differentiation by targeting SOX9(11), a master regulator of chondrocyte maturation that has also been implicated as an important regulator of the mammary stem cell state(12).

Long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) are noncoding RNA molecules greater than 200 nucleotides in size that are often critical regulators of gene expression. A majority of lncRNAs are intergenic (long intergenicncRNA (lincRNA))(13). They are transcribed by RNA pol II, polyadenylated, spliced, and 5’-capped(14). LncRNAs are functionally diverse and can act as guides, tethers, decoys, and scaffolds(15).A new function of lncRNA has also been proposed, that of competitive endogenous RNA (ceRNA) for miRs or naturally occurringmiR sponges. Such ceRNA networks have been identified as key regulators of muscle differentiation(16)and in the PTEN tumor suppressor pathway(17).

Recently, lncRNAs were implicated in stem cell pluripotency. Loewer et al. identified lincRNA-RoR (Regulator of Reprogramming) as a major regulator of pluripotency by examining lncRNA expression following fibroblast reprogramming into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs)(18). lincRNA-RoR was dramatically upregulated in pluripotent cells. Furthermore, they found that lincRNA-RoRwas essential for iPSC derivation.Wang et al. also examined the role of lincRNA-RoR in ESCs and found that lincRNA-RoR is essential for ESC pluripotency(19). Furthermore they found that lincRNA-RoR functions as ceRNA for miR-145 thereby protecting core pluripotency factors from miR-mediated silencing.This group found that this interaction led to loss of mature miR-145 expression. Using RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP) experiments they validated the interaction of miR-145 with lincRNA-RoR, which they found could be disrupted by mutating bases in the target sites for miR-145 seed pairing.

ARF proteins (ARF1-6) are small GTPases that regulate membrane protein trafficking and endocytosis(20). ARF6 was previously implicated in tumor cell invasion in breast(21), brain(22), and skin(23, 24) cancer. In breast cancer ARF6 was found to be essential for tumor cell invasive phenotype(21). Hyperactivation of ARF6 was able to impart metastatic characteristics to non-metastatic breast cancer cells. It was hypothesized that ARF6 may function by inhibiting cell-cell adhesion or regulating formation of invadipodia. This group found that protein but not mRNA levels of ARF6 correlated with breast tumor invasiveness and suggested that in metastatic breast cancer, ARF6 was likely regulated via posttranscriptional mechanisms(21). It is possible that miRs may play an important role in regulating ARF6 expression.

Here, we find that in TNBC loss of miR-145 promotes tumor cell invasion where activation of mIR-145 can inhibit invasion. We examine the molecular mechanisms for miR-145 loss and find that overexpression of lincRNA-RoR in breast tumors may function as ceRNA thereby silencing miR-145. Next, we identify a novel target of miR-145, the small GTPase ARF6, which was previously implicated in the breast tumor invasive process. We find that competitive inhibition of miR-145 by lincRNA-RoR results in ARF6 overexpression. We examine the function of ARF6 in breast cancer cells and find that ARF6 can impact cell-cell adhesion (via localization of E-cadherin) and tumor cell invasion.Furthermore, we find that in clinical samples ARF6 protein levels are higher in lymph node metastasis compared with primary tumors, suggesting this protein may play an important role in the metastatic process.

Methods

Cell culture

HEK293T, MCF-7, HS578T, &MDA-MB-231 cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) with 5% FBS and 1% glutamine (Invitrogen; Carlsbad, CA). MCF10A were grown in DMEM/F-12 medium supplemented with 10 μg/ml insulin, 100 ng/ml cholera toxin, 0.5 μg/ml hydrocortisone (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), 20 ng/ml EGF, and 5% horse serum (Invitrogen). Cells were grown at 37°C in an atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

Human Tissue array

Immunostaining of paraffin-embedded breast tumor tissue microarray (BR952, US Biomax, Rockville, MD) was performed to detect ARF6 protein expression. Additional paraffin-embedded DCIS samples were obtained from the University of Maryland Pathology Biorepository and Research Core. Sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated using xylene and gradient ethanol. Antigens were retrieved by boiling in sodium citrate(10mM, pH 6.0), which was proceeded by blocking in 10%, Goat Serum in PBS for 1 hour. This was followed by overnight incubation (at 4°C) withmouse anti-ARF6, 1:200 in blocking buffer (Santa Cruz sc7971, Santa Cruz, CA) followed with biotin goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (1:200). Avidin-biotin peroxidase substrate kit (Vector Laboratories; Burlingame, CA) was used to develop brown precipitate. Hematoxylin was utilized for nuclei staining. Using light microscopy, cores were scored on a 0-3 scale (none, light, moderate, intense) for staining intensity of ARF6.

RNA Quantification

TotalRNA was extracted with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). Small RNA was converted to complimentary DNA using poly-A polymerase based First-Strand Synthesis kit (SABioscience; Flat Lake, MD). Subsequent miR analysis was performed by real time PCR with miR-145 primer assays (SABiosciences) normalizing to control U6 snRNA levels.Total RNA was converted to cDNA by first treating with DNase I to remove genomic DNA and then using M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) and oligodT12-18 or random hexamer primers. The following primers were used for qRT-PCR. ROR F: CTCAGTGGGGAAGACTCCAG, R: AGGAAGCCTGAGAGTTGGC. ARF6: F:ATGGGGAAGGTGCTATCCAAAATC R:GCAGTCCACTACGAAGATGAGACC, pri-miR-145: F:AGGGCCAGCAGCAGGC R:TCAGGAAATGTCTCTGGCTGTG, pre-miR-145: F:GTCCAGTTTTCCCAGGAATC R:AGAACAGTATTTCCAGGAAT. ARF6 and ROR data were normalized to GAPDH using the following primers: F: GAAGGTGAAGGTCGGAGTC, R: GAAGATGGTGATGGGATTTC.All real time PCR was carried out with the Light Cycler 480 II (Roche Diagnostics; Indianapolis, IN).

Western Blottingand Proliferation Assay

Western blotting was performed as previously described(25) using ARF6 (Santa Cruz 3A-1; Santa Cruz, CA), E-cadherin (BD Transduction, 610182; Franklin Lakes, NJ)or N-cadherin (Santa Cruz H-63) antibodies. Data were normalized to β-actin (Sigma; St. Louis, MO). For proliferation assays, 1×10ˆ4 MDA-MB-231 cells (control and overexpressing miR-145) were plated in 96-well plates. After 3 days MTT solution was added to wells (final [.5 mg/ml]). Cells were incubated for 4 hours at 37°C. Media was removed and MTT formazan crystals were solubilized in DMSO. Absorbance was measured at 560 nm in a microplatereader (Bio Rad).

Plasmids, Transfections and Luciferase Assay

pCMV-MIR-145 expression vector and pCMV-MIR control vectors were obtained from Origene (Rockville, MD). pBabe-lincRNA-RoR was obtained from Addgene (plasmid 45763). shRNA for lincRNA-RoR and scramble control shRNA were purchased from Origene using pGFP-C-shLenti backbone and the following target sequence: GGAAGCCTGAGAGTTGGCATGAAT and loop: TCAAGAG. Constitutively active ARF6 (Q67L) expression vector was obtained from Addgene (plasmid 10835). ARF6 3’UTR was amplified using the following primers: F: CAGTACGCTAGCACCTGCTCCAGTCACCAATGR: CAGTACCTCGAGAAACTTAGCCCACAGTGGCA. PCR product was cloned downstream luciferase ORF into NheI and XhoI sites in pSGG 3’UTR reporter(SwitcGear Genomics). For pSGG-RORluciferase reporter construct, ROR cDNA was amplified using the primers 5’-ACAATGCTCGAGTTTATTTTTTGAGGAACTGTCATA-3’ and 5’- ACAATGGCTAGCGGTGAAATAAACAGCCATGTTGCT-3’ and cloned into the NheI and XhoI sites of pSGG vector. Transient transfections were performed using lipofectamine 2000 according to manufacturers instructions (Invitrogen). Stable infections were performed for lentiviral constructs. Briefly, HEK293T cells were transfected with 2nd generation lentiviral packaging constructs and expression constructs. After 12h medium was changed and at 24h and 48h lentivirus containing supernatant was harvested. Cells were infected with virus containing medium containing 8 μg/ml polybrene (American Bioanalytical, Natick, MA). Luciferase reporter assays were performed as previously described using dual luciferase assay system (Promega; Madison, WI) normalizing to Renilla luciferase activity(26).

tet-ON-lincRNA-RoR

The ROR cDNA was amplified by PCR using primers 5’-ACAATGGAATTCTTTATTTTTTGAGGAACTGTCATA-3’ and 5’-ACAATGGAATTCGGTGAAATAAACAGCCATGTTGCT-3’, and cloned into the EcoRI sites of FUW-teto vector (Addgene: 20326). Cells were cotransfected with FUW-M2rtTA (Addgene20342) at 1:8 ratio.

FluorescenceIn Situ Hybridization of lincRNA-RoR

Cy3-labed lincRNA-RoR probe was obtained from Exiqon (Woburn, MA). Cells were fixed in 4% formaldehyde and permeabilized using 0.5% Triton-X-100 in PBS, followed by blocking with 3% BSA in 4x saline-sodium citrate buffer. Cells were hybridized for 1 hour at 60°C with lincRNA-RoR probes (2 ng/ml dilution in buffer containing 10% dextran sulfate in 4x saline-sodium citrate buffer). Cells were washed in 4x, 2x, 1x saline-sodium citrate buffer and slides mounted in Prolong Gold.

MS2-binding Assay

ROR-MS2 construct. 24 MS2 binding sites were cloned downstream of pBABE-linc-ROR. The Phage-cmv-cfp-24xms2 vector (Addgene 40651) was digested with BamHI, treated with T4 DNA polymerase and then digested with AgeI. The vector backbone was recovered.The ROR cDNA was amplified by PCR using the primers 5’-ACAATGACCGGTGGTGAAATAAACAGCCATGTTGCT -3’ and 5’-ACAATGCTCGAGTTTATTTTTTGAGGAACTGTCATA -3’, treated with T4 DNA polymerase and AgeI sequentially and cloned into the phage-cmv-24xms2 vector prepared as described above.phage-ubc-nls-ha-tdMCP-gfp(MS2-GFP) fusion construct was obtained formaddgene (plasmid 40649). Cells were cotransfected with ROR-MS2 and MS2-GFP constructs and GFP localization was monitored with confocal microscopy.

Three-Dimensional (3-D) cell culture and Immunofluorescence

MCF-10A cells were dissociated into single cells and cultured with DMEM/F-12 containing 5% Matrigel, 5% heat-inactivated FBS, 0.5 μg/ml hydrocortisone, 100 ng/ml cholera toxin, 10 μg/ml insulin, 10 ng/ml EGF, and 5 μM Y-27632. Cells were embedded into matrigel-coated chamber-slides and grown for 7–14 days with replacement of fresh assay medium every 4 days. MDA-MB-231 cells transfected with control or miR-145 expression vectors were grown in chamber slides for 48 hours. Fluorescence was visualized using an Olympus IX81 spinning disk confocal microscope. Immunofluorescence staining was performed as previously described(27)by co-staining withARF6 and E-cadherin antibodies or Ki67 antibody (Sigma, SAB4501880) followed by Alexa Fluor conjugated secondary antibodies (Life Technologies) and DAPI counterstaining

Transwell invasion assay

Invasion assays were carried out using Transwell migration chambers (8μm pore size; Costar; Cambridge, MA) coated with 0.5mg/ml Matrigel (BD Science; Franklin Lakes, NJ) on top of the membrane. 0.5×10ˆ5 cells/ml were seeded in the upper chamber in serum free medium. The lower chamber contained 15% FBS. The cells were allowed to migrate towards the 15% FBS gradient overnight. Non-migrated cells on the top of the membrane were removed with cotton swabs. The migrated cells were stained with 1% crystal violet in methanol/PBS and counted using a light microscope.

The Cancer Genome Atlas TCGA

Data from the TCGA was analyzed using the UCSC Cancer Genome Browser (http://genome-cancer.soe.ucsc.edu/). The publically available dataset analyzed was the TCGA breast invasive carcinoma (BRCA) exon expression by RNAseq (IlluminaHiSeq) N=1160. ER, PR, and HER2 status were analyzed using UCSC Cancer Browser tools.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Student’s t test and p values of < 0.05 were considered significant. Data were represented as mean ± S.E. GraphPad Prism 4.0 software was used for all data analysis

Results

miR-145 is downregulated in TNBC where miR-145 regulates breast tumor cell invasion

The molecular underpinnings of TNBC are poorly understood and as such, there are no available molecularly targeted therapies. To gain a better understanding of the pathways driving tumorigenesis in TNBC we began by examining the unique miR signatures of this BC subtype. Analysis of breast tumor deep sequencing data had previously revealed that miR-145 loss is a hallmark of TNBC(4). We began our study by using publicly available databases to verify previous observations regarding miR-145 expression. We examined RNAseq data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), which contained data from 1,106 breast cancer patient samples. As shown in Fig. 1A, miR-145 is downregulated in nearly every breast tumor sample compared to normal breast tissue (fold Δ and p-value shown in Supp Fig. 1)(28). Furthermore, we examined ER, PR, and HER2 status in patient data from TCGA and found that TNBC patients clustered with the tumors having the lowest miR-145 expression. We also examined miR-145 expression in several samples of invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC) and matched normal tissue and again identified miR-145 loss in all samples of breast tumor tissue. (Fig. 1B) Next, we examined TNBC cell models MDA-MB-231 and HS578T compared with non-tumorigenic mammary epithelial cell line MCF10A and the ER positive breast cancer cell line MCF-7. We observed the strongest repression of miR-145 in TNBC models compared to non-tumorigenic mammary epithelial cells or ER positive breast cancer cells (Fig. 1C). Combined with previous studies, these data strongly indicate that miR-145 is dramatically silenced in TNBC.

Figure 1. miR-145 is downregulated in TNBC cells where miR-145 regulates breast tumor cell invasion.

A, RNAseq data for miR-145 in a breast tumor dataset from The Cancer Genome Atlas. B, Expression profiling of miR-145 in normal and breast tumor tissues via qRT-PCR with normalization to U6 snRNA. C, miR-145 expression measured in non-tumorigenic MCF-10A mammary epithelial cells and compared to MCF-7 (ER+), HS578T (TNBC) and MDA-MB-231 (TNBC) tumor cells. D, Cell proliferation as measured by MTT assay for MDA-MB-231 cells transfected with control or miR-145 expression plasmids. E&F, MDA-MB-231 cells overexpressing miR-145 were cultured in transwell invasion assays. * p< 0.05

Next, we began investigating what function miR-145 may play in TNBC. In ER positive BC, miR-145 was previously shown to regulate tumor cell proliferation(29). We examined the impact of miR-145 overexpression on the proliferation on MDA-MB-231 cells. We found that in TNBC cells miR-145 activation failed to significantly impact cell proliferation as examined via MTT assay (Fig. 1D). Furthermore, we also examined cell proliferation by performing Ki67 staining. We found that nearly 100% of control MDA-MB-231 cells and miR-145 overexpressing cells positively stained for nuclear Ki67, indicating active proliferation (Supp. Fig. 2A).We next examined what impact miR-145 might have on tumor cell invasion in TNBC. We grew cells on matrigel coated transwell inserts and tested the impact of miR-145 overexpression. We found that miR-145 overexpressing TNBC cells demonstrated a significant decrease in tumor cell invasion compared to control cells (Fig. 1 E&F). This data suggests that miR-145 may regulate invasion-related gene expression in TNBC. We also confirmed these results in a separate TNBC cell line, HS578T, again finding miR-145 impacts invasion but not proliferation in TNBC cells (Supp. Fig. 2 B&C).

lincRNA-RoR is overexpressed in TNBC where it serves as competitive endogenous RNA for miR-145

We next wanted to identify the molecular mechanisms responsible for miR-145 downregulation in TNBC. It was recently shown that in ESCs miR-145 is subject to posttranscriptional regulation via competitive endogenous RNA(19). lincRNA-RoR was found to contain miR-145 binding elements and function as a competitive sponge for miR-145 binding. To test if lincRNA-RoR might regulate miR-145 in TNBC we began by examining the expression profile of lincRNA-RoR in normal breast tissue, early stage tumors (Ductal Carcinoma In situ, DCIS), and invasive breast tumors (Invasive Ductal Carcinoma, IDC) using qRT-PCR. We found that lincRNA-RoR was significant upregulated in DCIS and IDC tumor tissues, showing the highest expression in invasive tumor tissues (Fig. 2A). Next, we examined lincRNA-RoR in breast cancer cell lines. We found that lincRNA-RoR was significantly overexpressed in MDA-MB-231 and HS578T TNBC cells when compared to normal tissue (Fig. 2B). Subsequently, we wanted to examine cellular localization of lincRNA-RoRto probe its potential to interact with cytoplasmic miR-145. We performed in situ hybridization and were able to detect lincRNA-RoR in the cytoplasm and nucleus of breast cancer cells (Supp Fig. 3A). For further confirmation, we performed MS2 binding assays, in which we cloned 24 MS2 binding sites downstream of lincRNA-RoR, and tested the ability for a GFP-MS2 fusion protein with a nuclear localization signal to sequester lincRNA-RoR-MS2 in the cytoplasm. In the absence of lincRNA-RoR-MS2, all the GFP-MS2 is localized in the nucleus (Supp Fig. 3B). However, in the presence of lincRNA-RoR-MS2, there are foci of GFP-MS2 in the cytoplasm. These results also support the cyoplasmic localization of lincRNA-RoR where it may interact with miR-145.

Figure 2. LincRNA-RoR is overexpressed in TNBC where it serves as competitive endogenous RNA for miR-145.

A, lincRNA-RoR expression in breast tumor tissues as measured by qRT-PCR. B, lincRNA-RoR expression in breast cancer cell lines. C, micRoRNA-145 response element in lincRNA-RoR as predicted by MiRanda 4.0 algorithm. D, miR-145 expression analysis following lincRNA-RoR overexpression in HEK-293T cells. E, lincRNA-RoR expression analysis following miR-145 overexpression in HEK-293T cells. F, Luciferase reporter assay for lincRNA-RoR in HEK-293T cells overexpressing miR-145. G, miR-145 expression analysis in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells following lincRNA-RoR overexpression. H, Fluorescent images of MDA-MB-231 cells stably infected with lincRNA-RoRshRNA. I, Expression analysis of lincRNA-RoR and miR-145 following lincRNA-RoR knockdown via qRT-PCR.* p< 0.05

We next wanted to confirm the interaction of miR-145 with the sites predicted by Miranda(30) targeting algorithms (Fig. 2C). We began by testing the impact of lincRNA-RoR overexpression on miR-145 levels in HEK-293t cells (which lack lincRNA-RoR expression). We found that lincRNA-RoR overexpression resulted in a significant decrease in miR-145 levels (Fig. 2D). Next, we examined the impact of co-transfection of miR-145 and lincRNA-RoR and found that co-transfection overcame the negative repression of endogenous miR-145 and resulted in decreasing lincRNA-RoR levels. This suggests a tug of war between these 2 molecules with some threshold where either the miR or the lincRNA gains the upper hand and silences its partner. We also cloned lincRNA-RoR sequence into a luciferase miR reporter construct to examine the ability of miR-145 to bind sequences in lincRNA-RoR. We found that miR-145 overexpression resulted in decreased luciferase activity compared to control cells (Fig. 2F) indicating miR-145 binding to sites in lincRNA-RoR. Next, we examined this interaction in breast cancer cell lines. We found that lincRNA-RoR overexpression resulted in decreasing mature, but not primary or precursor miR-145 levels in MDA-MB-231 TNBC cells (Fig. 2G). Finally, using lentiviralshRNA we knocked down lincRNA-RoR in MDA-MB-231 cells and found that this lead to an increase in miR-145 expression. Taken together, these results suggest that in TNBC cells lincRNA-RoR can function as a sponge and repress miR-145 expression.

Finally, we examined whether lincRNA-RoR regulation of miR-145 could impact breast cancer cell invasion. We transfected MCF7 cells with tetON-lincRNA-RoR + rtTA and after 24h induced lincRNA- RoR expression with 100 ng/mL Doxycycline. Induced cells were grown atop matrigel coated transwell inserts and cells were allowed to migrate for 24h. Following 24 hours, we observed a significant increase in invasive cells, whereas control MCF7 cells showed little to no invasive activity (Supp. Fig. 4A).

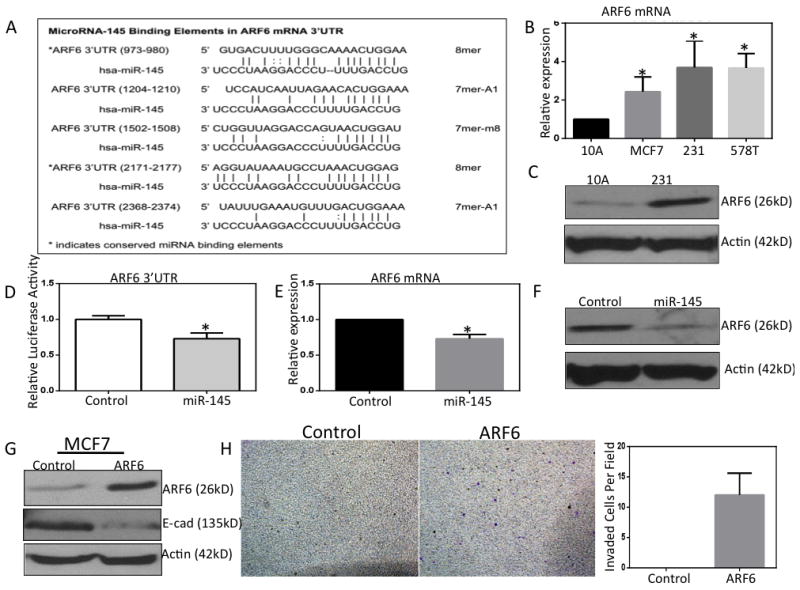

miR-145 directly targets the 3’UTR of ARF6 mRNA

In addition to understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying the regulation of miR-145, we wanted to probe what invasive pathways miR-145 might regulate in TNBC cells. We examined computationally predicted targets of miR-145 using TargetScan algorithm(31). Among the highest scoring predicted mRNA targets of miR-145 was ADP-ribosylation factor 6 (ARF6). ARF6 is a small GTPase that has been previously implicated as a critical regulator of tumor cell invasion in metastatic breast cancer(21). A previous proteomics study revealed that miR-143/145 modulation altered ARF6 protein levels in colon cancer cells suggesting ARF6 might be a direct target for miR-145(32). ARF6 mRNA 3’-untranslated region (3’UTR) contains an impressive 5 predicted miR-145 binding elements (Fig. 3A). We began by examining ARF6 expression in TNBC. We found that ARF6 demonstrated inverse expression relative to miR-145. ARF6 was dramatically overexpressed in TNBC cells compared to non-tumorigenic mammary epithelial cells (Fig. 3 B&C). To test the predicted binding of miR-145 to ARF6 mRNA we cloned the ARF6 3’UTR downstream a luciferase ORF and performed luciferase reporter assays for ARF6 3’UTR. We found that overexpression of miR-145 resulted in a significant decrease in luciferase activity compared with control cells (Fig. 3D). Next, we examined ARF6 expression in MDA-MB-231 cells following miR-145 overexpression. We detected a small but significant decrease in ARF6 mRNA levels following miR-145 overexpression (Fig. 3E). However, following miR-145 overexpression we detected a dramatic decrease in ARF6 protein levels (Fig. 3F). These data suggest that miR-145 inhibition of ARF6 is mostly occurring by interfering with ARF6 translation.Finally, to test if our previously interaction between lincRNA-RoR and miR-145 impact the targeting of ARF6 mRNA by miR-145 we examined ARF6 protein levels following knockdown of lincRNA-RoR by shRNA.We found that knockdown of lincRNA-RoR in MDA-MB-231 cells resulted in decrease in ARF6 protein (Supp Fig. 4B). These results support a lincRNA-RoR/miR-145/ARF6 pathway in TNBC cells.

Figure 3. miR-145 directly targets the 3’UTR of ARF6 mRNA.

A, Table of the predicted miR-145 binding sites in the ARF6 mRNA 3’UTR as predicted by TargetScan algorithm. B, ARF6 mRNA expression in breast cancer cell lines via qRT-PCR. C, ARF6 protein expression in MDA-MB-231 cells. D, Luciferase reporter for ARF6 mRNA 3’UTR following miR-145 overexpression. E, ARF6 mRNA levels in MDA-MB-231 cells following miR-145 overexpression. F, ARF6 protein levels in MDA-MB-231 cells following miR-145 overexpression. G&H, MCF-7 cells overexpressing constitutively active ARF6. A loss of E-cadherin demonstrated via western blotting and a more invasive phenotype as evidenced by matrigel coated invasion assays. * p< 0.05

It was previously reported that ARF6 might contribute to breast cancer invasion via regulating or by regulating cell-cell adhesion through controlling E-cadherin localization(33, 34). This group found that in the presence of EGF ligand (activating EGFR signaling) that ARF6 was able to repress E-cadherin at the protein level. We examined the impact of overexpression of constitutively active ARF6 on the invasive activities of non-metastatic MCF-7 breast cancer cells. As confirmation of the earlier observations, we found that in the presence of EGF, MCF-7 cells overexpressing ARF6 showed a decrease in E-cadherin protein levels (Fig. 3G). Furthermore, MCF-7 cells overexpressing ARF6 were capable of invading matrigel in transwell invasion assays as evidenced by the staining of invasive protrusions on the bottom of transwell inserts, whereas control MCF-7 cells demonstrated no invasive capabilities in this assay (Fig. 3H).

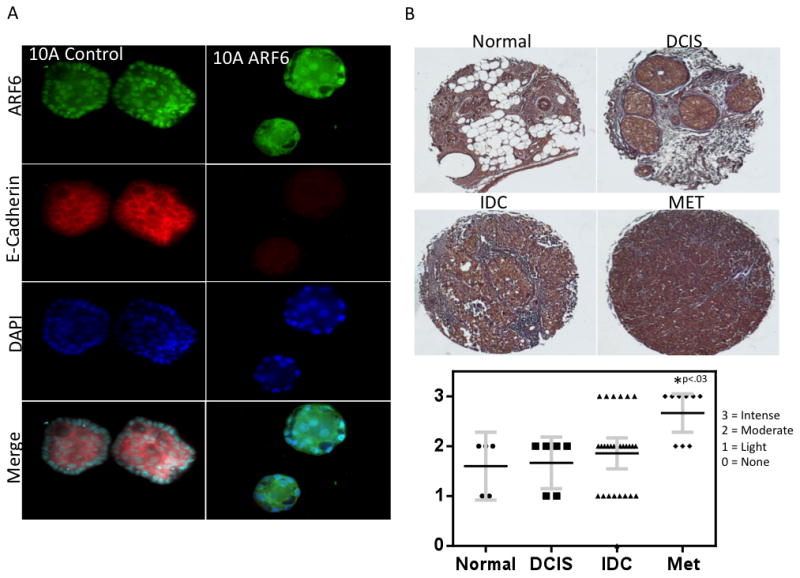

ARF6 overexpression alters E-cadherin localization and disrupts cell-cell junctions

To further examine the potential importance of ARF6 overexpression in BC we performed gain of function studies in MCF10A non-tumorigenic mammary epithelial cells. We performed 3-D cell culture experiments with MCF10A cells overexpressing ARF6 and examined E-cadherin localization using immnofluorescence. 3-D cell culture can be used to recapitulate mammary organogenesis where control MCF10A cells grow into hollow acinar structures with polarized luminal and basolateral surfaces. Control MCF10A cells formed hollow acinii structures with E-cadherin localization to cell-cell junctions (Fig. 4A). In ARF6 overexpressing MCF10A cells there was an obvious loss of E-cadherin expression and localization to cell-cell junctions. Furthermore, morphology of ARF6 overexpressing acinii was altered with greater spacing between nuclei as evidenced by DAPI staining, suggesting a disruption in cell-cell junctions.

Figure 4. The miR-145 Target ARF6 is overexpressed in lymph node metastasis.

A, 3-D cell culture of MCF-10A cells stably infected with ARF6. Cells are grown in EGF supplemented media (10 ng / ml) for 7 days followed by fixation and staining with ARF6 and E-Cadherin antibodies followed by DAPI counterstaining. Acinii were examined via confocal microscopy. B, Immunohistochemistry for ARF6 was performed on a tissue microarray of matched normal and breast tumor tissue including matched primary and lymph node metastasis core samples. Normal tissue n=5, DCIS n=6, IDC n = 26, MET n = 9.

The miR-145 Target ARF6 is overexpressed in lymph node metastasis

As there is previously no clinical data suggesting ARF6 expression is associated with breast tumor invasiveness, we examined ARF6 expression using immunohistochemistry in a tissue microarray with core samples from matched normal breast, primary tumor, and lymph node metastasis (Fig. 4B). We detected higher levels of ARF6 in some samples of primary tumor (IDC), however, it did not account for a statistically significant difference with ARF6 levels detected in our normal breast tissue. On the other hand, we did detect a statistically significant increase in ARF6 staining in lymph node metastasis cores (p < 0.03). These data offer support for the clinical relevance of ARF6 in breast cancer metastasis.

Discussion

Deep sequencing studies have previously shown that miR-145 downregulation is a hallmark of triple negative breast cancer (TNBC)(4). Here, using transwell invasion assays we have found that miR-145 regulates tumor cell invasion in TNBC and not apoptosis or proliferation. We examined the molecular mechanism responsible for miR-145 downregulation in TNBC and found that the long intergenic non-coding RNA RoR (“Regulator of Reprogramming”) regulates mature miR-145 by serving as a competitive endogenous RNA sponge. This is the first report of this ceRNA network in human cancer.

To better understand the function of miR-145 in TNBC we examined the predicted targets of miR-145 and identified ADP-Ribosylation Factor 6 (ARF6), a small GTPase known to regulate endocytic recycling and previously implicated in breast tumor invasion(21). ARF6 mRNA 3’UTR contains 5 predicted miR-145 binding sites. Using a 3’UTR luciferase reporter, qRT-PCR, and western blotting we validated miR-145 targeting of the 3’UTR of ARF6 mRNA. Next, we found that ARF6 overexpression in MCF-7 cells promoted a more invasive phenotype as evidenced by transwell invasion assays. We examined ARF6 function via 3-D cell culture and found that overexpression of ARF6 results in loss of E-Cadherin localization and disruption of cell-cell junctions. Finally, we examined ARF6 expression in a breast tumor tissue array and found that ARF6 levels were significantly higher in lymph node metastasis suggesting a role of ARF6 in breast cancer metastasis. Based on our in vitro findings, it is important to next examine whether miR-145 and ARF6 can regulate TNBC metastasis in vivo.

Previously, miR-145 and lincRNA-RoR have been implicated in embryonic and adult stem cells(10). These molecules may also be critical regulators of cancer stem cell biology as it was previously reported that miR-145 is silenced in breast cancer stem cells. The Weinberg group has thoroughly demonstrated that there is powerful connection between EMT and breast cancer stem cell(12). Here, we have demonstrated a connection between miR-145 and invasion/metastasis that involves altered cell morphology and loss of epithelial adherens junction protein E-cadherin. In future studies it will be interesting to test whether miR-145 and lincRNA-RoR play important roles in regulating the cancer stem cell phenotype in TNBC, which has previously been shown to play a critical role in drug resistance and metastasis.

Supplementary Material

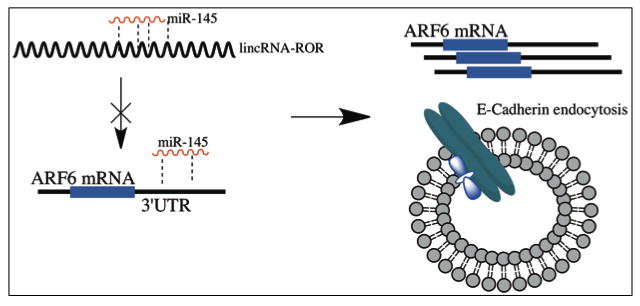

Figure 5. Illustration of miR-145 regulation of TNBC invasion.

This is our proposed model for miR-145 regulation of TNBC invasion. Competition between lincRNA-RoR and miR-145 prevents miR-mediated suppression of ARF6, this in turn leads to overexpression of ARF6 and altered E-cadherin localization.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NCI F31 CA183522 (to G.E.) and by grants from ACS, and the NCI R01 (to Q. Z.)

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Siegel R, Ward E, Brawley O, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2011. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2011;61(4):212–36. doi: 10.3322/caac.20121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foulkes WD, Smith IE, Reis-Filho J. Triple-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(20):1938–48. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1001389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carey LA, Perou CM, Livasy CA, et al. Race, breast cancer subtypes, and survival in the carolina breast cancer study. JAMA. 2006;295(21):2492–502. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.21.2492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Volinia S, Calin GA, Liu CG, et al. A micRoRNA expression signature of human solid tumors defines cancer gene targets. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:2257–61. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510565103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cho WCS, Chow ASC, Au JSK. MiR-145 inhibits cell proliferation of human lung adenocarcinoma by targeting EGFR and NUDT1. RNA Biology. 2011;8(1):125–31. doi: 10.4161/rna.8.1.14259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zaman MS, Chen Y, Deng G, et al. The functional significance of micRoRNA-145 in prostate cancer. Br J Cancer. 2010;103(2):256–64. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iorio MV, Ferracin M, Liu CG, et al. MicRoRNA gene expression deregulation in human breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2005;65:7065–70. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang J, Guo H, Zhang H, et al. Putative tumor suppressor miR-145 inhibits colon cancer cell growth by targeting oncogene friend leukemia virus integration 1 gene. Cancer. 2011;117(1):86–95. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chiyomaru T, Enokida H, Tatarano S, et al. miR-145 and miR-133a function as tumour suppressors and directly regulate FSCN1 expression in bladder cancer. Br J Cancer. 2010;102(5):883–91. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu N, Papagiannakopoulos T, Pan G, Thomson JA, Kosik KS. MicRoRNA-145 regulates OCT4, SOX2, and KLF4 and represses pluripotency in human embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2009;137(4):647–58. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang B, Guo H, Zhang Y, Chen L, Ying D, Dong S. MicRoRNA-145 regulates chondrogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells by targeting Sox9. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(7):e21679. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guo W, Keckesova Z, Donaher J, et al. Slug and Sox9 cooperatively determine the mammary stem cell state. Cell. 2012;148(5):1015–28. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harrow J, Frankish A, Gonzalez JM, et al. GENCODE: The reference human genome annotation for the ENCODE project. Genome Res. 2012;22(9):1760–74. doi: 10.1101/gr.135350.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guttman M, Amit I, Garber M, et al. Chromatin signature reveals over a thousand highly conserved large non-coding RNAs in mammals. Nature. 2009;458(7235):223–7. doi: 10.1038/nature07672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rinn JL, Chang HY. Genome regulation by long noncoding RNAs. Annu Rev Biochem. 2012;81(1):145–66. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-051410-092902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cesana M, Cacchiarelli D, Legnini I, et al. A long noncoding RNA controls muscle differentiation by functioning as a competing endogenous RNA. Cell. 147(2):358–69. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.09.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tay Y, Kats L, Salmena L, et al. Coding-independent regulation of the tumor suppressor PTEN by competing endogenous mRNAs. Cell. 147(2):344–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Loewer S, Cabili MN, Guttman M, et al. Large intergenic non-coding RNA-RoR modulates reprogramming of human induced pluripotent stem cells. Nat Genet. 2010;42(12):1113–7. doi: 10.1038/ng.710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang Y, Xu Z, Jiang J, et al. Endogenous miRNA sponge lincRNA-RoR regulates Oct4, nanog, and Sox2 in human embryonic stem cell self-renewal. Dev Cell. 2013;25(1):69–80. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gillingham AK, Munro S. The small G proteins of the arf family and their regulators. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2007;23(1):579–611. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.23.090506.123209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hashimoto S, Onodera Y, Hashimoto A, et al. Requirement for Arf6 in breast cancer invasive activities. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(17):6647–52. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401753101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hu B, Shi B, Jarzynka MJ, Yiin J, D’Souza-Schorey C, Cheng S. ADP-ribosylation factor 6 regulates glioma cell invasion through the IQ-domain GTPase-activating protein 1-Rac1 Mediated pathway. Cancer Res. 2009;69(3):794–801. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grossmann AH, Yoo JH, Clancy J, et al. The small GTPase ARF6 stimulates {beta}-catenin transcriptional activity during WNT5A-mediated melanoma invasion and metastasis. Sci Signal. 2013;6(265):ra14. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2003398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muralidharan-Chari V, Hoover H, Clancy J, et al. ADP-ribosylation factor 6 regulates tumorigenic and invasive properties in vivo. Cancer Res. 2009;69(6):2201–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eades G, Yang M, Yao Y, Zhang Y, Zhou Q. miR-200a regulates Nrf2 activation by targeting Keap1 mRNA in breast cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(47):40725–33. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.275495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eades G, Yao Y, Yang M, Zhang Y, Chumsri S, Zhou Q. miR-200a regulates SIRT1 expression and epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT)-like transformation in mammary epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(29):25992–6002. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.229401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li Q, Yao Y, Eades G, Liu Z, Zhang Y, Zhou Q. Downregulation of miR-140 promotes cancer stem cell formation in basal-like early stage breast cancer. Oncogene. 2013 doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li J, Liu S, Zhou H, Qu L, Yang J. starBase v2.0: Decoding miRNA-ceRNA, miRNA-ncRNA and protein-RNA interaction networks from large-scale CLIP-seq data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D92–7. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang SF, Bian CF, Yang ZF, et al. miR-145 inhibits breast cancer cell growth through RTKN. Int J Oncol. 2009;34(5):1461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.John B, Enright AJ, Aravin A, Tuschl T, Sander C, Marks DS. Human MicRoRNA targets. PLoS Biol. 2004;2(11):e363. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Friedman RC, Farh KK, Burge CB, Bartel DP. Most mammalian mRNAs are conserved targets of micRoRNAs. Genome Res. 2009;19(1):92–105. doi: 10.1101/gr.082701.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bauer KM, Hummon AB. Effects of the miR-143/-145 MicRoRNA cluster on the colon cancer proteome and transcriptome. J Proteome Res. 2012;11(9):4744–54. doi: 10.1021/pr300600r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Valderrama F, Ridley AJ. Getting invasive with GEP100 and Arf6. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10(1):16–8. doi: 10.1038/ncb0108-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morishige M, Hashimoto S, Ogawa E, et al. GEP100 links epidermal growth factor receptor signalling to Arf6 activation to induce breast cancer invasion. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10(1):85–92. doi: 10.1038/ncb1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.