Abstract

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of premature mortality in the developed world, and hypertension is its most important risk factor. Controlling hypertension is a major focus of public health initiatives, and dietary approaches have historically focused on sodium. While the potential benefits of sodium-reduction strategies are debatable, one fact about which there is little debate is that the predominant sources of sodium in the diet are industrially processed foods. Processed foods also happen to be generally high in added sugars, the consumption of which might be more strongly and directly associated with hypertension and cardiometabolic risk. Evidence from epidemiological studies and experimental trials in animals and humans suggests that added sugars, particularly fructose, may increase blood pressure and blood pressure variability, increase heart rate and myocardial oxygen demand, and contribute to inflammation, insulin resistance and broader metabolic dysfunction. Thus, while there is no argument that recommendations to reduce consumption of processed foods are highly appropriate and advisable, the arguments in this review are that the benefits of such recommendations might have less to do with sodium—minimally related to blood pressure and perhaps even inversely related to cardiovascular risk—and more to do with highly-refined carbohydrates. It is time for guideline committees to shift focus away from salt and focus greater attention to the likely more-consequential food additive: sugar. A reduction in the intake of added sugars, particularly fructose, and specifically in the quantities and context of industrially-manufactured consumables, would help not only curb hypertension rates, but might also help address broader problems related to cardiometabolic disease.

Keywords: sugar, fructose, sucrose, glucose

Key messages.

What is already known on this subject?

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of premature mortality in the developed world, and hypertension is its most important risk factor.

Controlling hypertension is a major focus of public health initiatives, and dietary approaches have historically focused on sodium.

What might this study add?

The predominant sources of sodium in the diet, processed foods, are also generally high in added sugars, the consumption of which might be more strongly and directly associated with hypertension and cardiometabolic risk.

How might this impact on clinical practice?

Clinicians should shift focus away from salt and focus greater attention to the likely more-consequential food additive: sugar.

A reduction in the intake of added sugars, particularly fructose, and specifically in the quantities and context of industrially-manufactured consumables, would help not only curb hypertension rates, but might also help address broader problems related to cardiometabolic disease.

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the number one cause of premature mortality in the developed world,1–3 and hypertension is its most important risk factor.4 Hypertension was implicated as a primary or contributing factor in more than 348 000 deaths in the USA in 20095 with costs to the nation in excess of $50 billion annually.6 Controlling hypertension is a major focus of public health initiatives, and dietary approaches to address hypertension have historically focused on sodium. Nonetheless, the potential benefits of sodium reduction are debatable.7–9 Reducing sodium intake may lower blood pressure measurements in some individuals, but average blood-pressure reductions might only be as great as 4.8 mm Hg systolic and 2.5 mm Hg diastolic—being generous (only considering upper confidence limits and only considering persons with hypertension)10—and whether there would be a net health benefit from such reductions is unclear. In fact, there is some evidence suggesting that reducing sodium intake could lead to worse health outcomes, such as increased cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in patients with diabetes,11 and increased hospitalisations and mortality in patients with congestive heart failure.12–15 More importantly, recent data encompassing over 100 000 patients indicates that sodium intake between 3 and 6 g/day is associated with a lower risk of death and cardiovascular events compared to either a higher or lower level of intake.16 17 Thus, guidelines advising restriction of sodium intake below 3 g/day may cause harm.

Strategies to lower dietary sodium intake focus (implicitly if not explicitly) on reducing consumption of processed foods: the predominant sources of sodium in the diet.18 For instance, the Food and Drug Administration has recently announced that it is drafting guidelines asking the food industry to voluntarily lower sodium levels.19

Nonetheless, the mean intake of sodium in Western populations is approximately 3.5–4 g/day.20 Five decades worth of data indicates that sodium intake has not changed from this level across diverse populations and eating habits, despite population-wide sodium-reduction efforts and changes in the food supply.21 22 Such stability in intake suggests tight physiologic control, which if indeed the case, could mean that lowering sodium levels in the food supply could have unintended consequences. Because processed foods are the principal source of dietary sodium,18 if these foods became less salty, there could be a compensatory increase in their consumption to obtain the sodium that physiology demands.

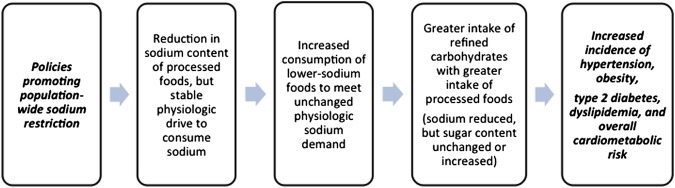

Coincidentally, processed foods happen to be major sources of not just sodium but of highly refined carbohydrates: that is, various sugars, and the simple starches that give rise to them through digestion. Compelling evidence from basic science, population studies, and clinical trials implicates sugars, and particularly the monosaccharide fructose, as playing a major role in the development of hypertension. Moreover, evidence suggests that sugars in general, and fructose in particular, may contribute to overall cardiovascular risk through a variety of mechanisms. Lowering sodium levels in processed foods could lead to an increased consumption of starches and sugars and thereby increase in hypertension and overall cardiometabolic disease (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Unintended consequences of population-wide sodium restriction.23

Basic-Science: sucrose, fructose, hypertension and cardiovascular risk

Sucrose, or table sugar, is a disaccharide composed of two monosaccharides: glucose and fructose. Sucrose is a common ingredient in industrially processed foods, but not as common as another sweetener: high-fructose corn syrup (HFCS). Whereas sucrose is equal parts fructose and glucose, HFCS has more fructose (usually 55%) than glucose (the remaining 45%) and is the most frequently used sweetener in processed foods, particularly in fruit drinks and sodas.24

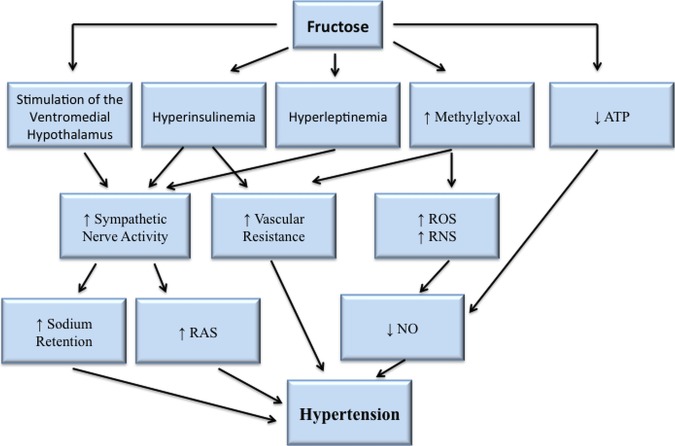

Feeding sucrose to rats stimulates the sympathetic nervous system (SNS),25 which leads to increases in heart rate,26 renin secretion, renal sodium retention and vascular resistance.27 All of these effects interact to elevate blood pressure and, indeed, feeding sucrose to rats increases their blood pressure.28–33 Sucrose feeding also induces other changes, like insulin resistance, as part of a broader metabolic dysfunction.28–33 Additionally, the consumption of sugar or HFCS may lead to an increase in blood pressure via other mechanisms, such as hyperleptinaemia, an increase in methylglyoxal, and a reduction in ATP (figure 2).23 Figure 2 describes the possible mechanisms through which fructose may contribute to hypertension.

Figure 2.

Hypertensive mechanisms of fructose.23 Arrows represent direct effects, or indirect effects through intermediates, which is not shown for simplicity. NO, nitric oxide; RAS, renin-angiotensin system; RNS, reactive nitrogen species; ROS, reactive oxygen species.23

Straight fructose induces similar results as sucrose when ingested—both in rodents28 34 35 and humans.36–42 Although high intakes of either fructose alone or sucrose may lead to insulin resistance,43–46 it is fructose that has been implicated as the sugar responsible for reducing sensitivity of adipose tissue to insulin.47 Insulin stimulates the SNS26 48–50 and hyperinsulinaemia may lead to hypertension, with the degree of insulin resistance in peripheral tissues directly correlated with hypertension severity.51 52 Reducing insulin resistance may lead to a reduction in blood pressure,48 and hyperinsulinaemia seems more related to fructose than glucose.53

Population studies: fructose and other sugars and cardiometabolic health

Insulin resistance is seen in approximately 25% of the general population and up to 80% of individuals with ‘essential’ hypertension.54 Compared to non-diabetics, diabetics have a higher prevalence of hypertension.55 56 This disproportion is independent of weight, suggesting that insulin resistance, not obesity per se, increases the risk of hypertension. Indeed, approximately 50% of hypertensive patients have hyperinsulinaemia compared to only 10% of normotensive patients.57 Additionally, hypertensive patients have decreased insulin sensitivity, increased basal insulin and a decreased rate of glucose disposal after an intravenous glucose tolerance test when compared to normotensives, even after adjustment for other risk factors.58 A diet high in sugar has been found to cause deterioration of glucose tolerance,59 and positive correlations exist between sugar consumed 20 years earlier and diabetes.60

A recent econometric analysis showed that an increase in sugar availability is directly and independently associated with an increase in diabetes prevalence.61 In fact, a 150-kilocalorie/person/day increase in sugar availability was found to be significantly associated with a rise in diabetes prevalence (1.1%, p<0.001). This risk was 11-fold higher compared to 150-kilocalorie/person/day increase in total calorie availability, supporting the notion that sugar may be distinct among calories in its potential detriment to metabolic health.

Compared to patients who consume less than 10% of their calories from added sugars, those who consumed 10.0–24.9% of their calories from added sugars have a 30% increased risk of mortality from CVD.62 Those who consume 25% or more calories from added sugars have an almost threefold increased risk.62 Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES 2003 to 2006) indicates a mean fructose intake of 83.1 g/day.63 Concerning, is that an intake >74 g/day of fructose is independently associated with 26%, 30% and 77% higher risks for blood pressures >135/85 mm Hg, 140/90 and 160/100, respectively.36 Consuming sugar-sweetened beverages has been directly associated with increased blood pressure in a study of almost 2700 people from 10 USA/UK populations, independent of body weight and height.64

In a systematic review of 12 studies (cross-sectional and prospective cohort) encompassing over 400 000 participants, sugar-sweetened beverage intake was significantly associated with higher blood pressure and an increased incidence of hypertension.65 The authors concluded that, “intake of >12 fL. oz. of sugar-sweetened beverage per day can increase the risk of having hypertension by at least 6%, and it can increase mean systolic blood pressure by a minimum of 1.8 mm Hg in roughly over 18 months.” Such beverages may contain substantially more fructose than once thought,66 67 and consumption of SSBs has been shown to increase the risk of not just hypertension, but of coronary heart disease, stroke and other cardiometabolic disease including obesity and diabetes.68–74 Worldwide, SSB consumption has been implicated in 180 000 deaths/year.75

Clinical trials: modifying sugar intake and CVD-related outcomes

Some individuals show a rise in blood pressure after just a few weeks on a high-sucrose diet (defined as 33% of total caloric intake from sucrose).76 In fact, a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials showed that higher sugar intake significantly increases systolic (6.9 mm Hg, p<0.0001) and diastolic blood pressure (5.6 mm Hg, p=0.0005) versus lower sugar intake in trials of 8 weeks or more in duration.77 Moreover, when studies that received funding from the sugar industry were excluded from the analysis, the magnitude of blood pressure elevation was even more pronounced (7.6 mm Hg systolic, 6.1 mm Hg diastolic on average). Higher sugar intake also significantly increased triglycerides, total cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein, independent of effects on body weight and when matched for calories (suggesting that sugars may promote dyslipidemia through mechanisms unrelated to any additional calories they supply).77 Nonetheless, trial data show that patients consuming 28% of their energy from sucrose (approximately 152 g of sucrose per day, mainly from beverages) for just 10 weeks have a significant increase in body weight (1.6 kg), as well as increases in fat mass (1.3 kg) in addition to increases in blood pressure (3.8 mm Hg systolic, 4.1 mm Hg diastolic).78

As for different effects from different sugars (eg, sucrose (fructose+glucose) vs fructose alone in particular), one study examined blood pressure responses to various sugar solutions in 20 healthy normotensive men.79 Ingestion of the sucrose solution significantly increased systolic blood pressure by 9 mm Hg. The increase in systolic blood pressure resulting from the fructose-only solution (4 mm Hg) was not statistically significant, however the lower response may have been due to poorer absorption of fructose unaccompanied by glucose.80 Nonetheless, fructose had the greatest antinatriuretic effect,80 suggesting a minimal role of sodium retention as a mechanism for blood-pressure response to added sugar intake. Another trial showed a more pronounced hypertensive response to drinking a HFCS (fructose+glucose)-sweetened beverage versus a sucrose-sweetened beverage in healthy individuals (15/9 mm Hg vs 12/9 mm Hg) and both drinks increased heart rate by 9 bpm.81

Other trials have suggested that fructose may be uniquely detrimental to the cardiovascular system. In a randomised cross-over study in young healthy adults (21–33 years old), ingestion of a fructose solution (60 g) increased systolic blood pressure (6.2±0.8 mm Hg).82 A similar increase in blood pressure was not seen with ingestion of a glucose solution but both drinks significantly increased heart rate and cardiac output.82 The authors concluded that fructose, but not glucose, may cause elevations in blood pressure by increasing cardiac output without a compensatory peripheral vasodilation; whereas both glucose and fructose increase blood pressure variability and myocardial oxygen demand. The marked increase in systolic blood pressure and blood pressure variability with fructose is concerning, as these are independent risk factors for macrovascular and microvascular complications in type 2 diabetics.83 Additionally, blood pressure variability is associated with an increased risk of stroke84 and the development of hypertension and target organ damage, even without changes in average blood pressure.85

Fructose may cause other cardiometabolic harm as well. In a randomised trial of 74 adult men, a high-fructose diet for just 2 weeks not only significantly increased 24 h ambulatory blood pressure (+7/5 mm Hg, p<0.004 and p=0.007, respectively) and increased pulse rate by 8% (4 bpm), but also increased triglycerides, fasting insulin and homeostatic model assessment index (a measure of insulin resistance and β-cell function).86 Additionally, fructose lowered levels of high-density lipoprotein and doubled the prevalence of metabolic syndrome, with 25–33% of patients developing the condition.86 Lowering fructose intake (from 59 to 12 g/day) has been shown to lower blood pressure, fasting insulin levels and inflammation in patients with chronic kidney disease.87

A critical dietary caveat

Importantly, it is likely only ‘added’ fructose and other sugars (eg, as found in processed foods and sugary beverages) that may be a problem. Naturally occurring sugars, including fructose, seem to be benign in their usual biological context (ie, in the context of accompanying water, fibre, and other carbohydrates, or even fats and proteins as in many whole plant foods). In fact, in one trial, switching from a Western diet, to a diet containing approximately 20 servings of whole fruit significantly decreased systolic blood pressure, despite a fructose intake of approximately 200 g.88 Moreover, a study randomising 131 patients to two low ‘added-fructose’ diets (a low-fructose diet of <20 g/day, and a moderate-fructose diet of 50–70 g/day including natural sources like fruits) showed comparable improvements from baseline in blood pressure, lipids, serum glucose, insulin resistance, uric acid, soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) and quality of life score.89

Current levels of sugar consumption and dietary guidelines

Approximately 300 years ago humans were only consuming a few pounds of sugar per year.90 More recent estimates suggest intakes in the US population anywhere from 77 to 152 lbs of sugar per year,91 92 with 13% consuming at least 25% of their total caloric intake as added sugars.63 This level of consumption equates to an approximate average intake of added sugars of 24–47 teaspoons (about 100–200 g) per day, with an average daily fructose consumption of 83.1 g.63 Table 1 suggests how such large intake may be possible, showing some representative foods and the sugar loads associated with their consumption.93 In a study of over 1000 American adolescents (aged 14–18) the average daily intake of added sugars was 389 g for boys and 276 g for girls, or up to 52% of total caloric intake.90 The level of added fructose intake implied by these numbers (at least 138 daily grams) is shocking, especially considering there is no physiological requirement for added sugar, particularly fructose, in the diet so potential harms of ingestion clearly outweigh any potential benefits.94

Table 1.

Amount of sugar in common food items93

| Food item | Amount of sugar (g) | Portion |

|---|---|---|

| Beverages | ||

| Mountain Dew | 77 | 20 oz |

| Sobe mango melon | 70 | 20 oz |

| Minute maid lemonade | 67 | 20 oz |

| Coca-cola | 65 | 20 oz |

| Rockstar energy drink | 62 | 16 oz |

| Vitamin water, B-relaxed jackfruit and guava flavor | 33 | 20 oz |

| Snacks | ||

| Yoplait yogurt, strawberry | 27 | 6 oz |

| Power bar, chocolate peanut butter | 23 | 1 bar |

| Breakfast foods | ||

| Cinnabon cinnamon roll | 55 | 1 pastry |

| Pop tarts, frosted cherry | 34 | 2 pastries |

| Frosted flakes gold cereal | 25 | 1 bowl |

| Nutrigrain cereal bar, strawberry | 13 | 1 bar |

| Sauces | ||

| Kraft spicy honey BBQ Sauce | 13 | 2 tablespoons |

| Heinz tomato ketchup | 8 | 2 tablespoons |

| Prego Marinara Spaghetti sauce | 7 | One-half cup |

The American Heart Association (AHA) makes no specific recommendations about fructose, but recommends no more than six teaspoons of sugar per day for women, and no more than nine teaspoons of sugar per day for men.95 The WHO likewise makes no specific recommendations about fructose, but recommends that added sugars should make up no more than 10% of our entire daily caloric intake, with a proposal to lower that level even further (to 5% or less) for optimal health.96 By teaspoons, the WHO advises no more than 6–12 teaspoons per day (based on a 2000 calorie per day diet). Even at the higher end, this is only slightly more than the amount of sugar in a single 12 oz. can of Coca-Cola (around 40 g of sugar/10 teaspoonful). Concerning, is that an entire 1 L bottle of Coca-Cola (at 400 calories) might be okay to drink by more liberal Institute of Medicine (IOM) recommendations, which allow an intake of added sugars up to 25% of total daily calories.97 Such allowance is a problem. Added sugar at this level may increase the risk of death due to CVD by almost threefold.62

Other dietary guidelines focus not on sugar, but salt. For instance, the 2013 AHA/American College of Cardiology (ACC) Guidelines on Lifestyle Management to Reduce Cardiovascular Risk recommend lowering sodium intake to 2400 mg/day with further reduction to 1500 mg/day in order to promote optimal reductions in blood pressure.98 Such dietary restrictions may not result in benefit, may produce harm, and may distract focus from other white crystals of greater concern.99 Sugar may be much more meaningfully related to blood pressure than sodium, as suggested by a greater magnitude of effect with dietary manipulation.10 77 There is no mention in the AHA/ACC guideline of reducing intake of added sugars to a specific level, and this deficiency is concerning. Still, as the most substantial dietary sources of sodium are also often the most substantial dietary sources of added sugars (ie, processed foods), advice to limit sodium consumption could coincidentally result in less sugar consumption as well. Hence even potentially misdirected dietary guidelines could serendipitously result in benefit.

Conclusion

High-sugar diets may contribute substantially to cardiometabolic disease. While naturally occurring sugars in the form of whole foods like fruit are of no concern, epidemiological and experimental evidence suggest that added sugars (particularly those engineered to be high in fructose) are a problem and should be targeted more explicitly in dietary guidelines to support cardiometabolic and general health.

Added sugars probably matter more than dietary sodium for hypertension, and fructose in particular may uniquely increase cardiovascular risk by inciting metabolic dysfunction and increasing blood pressure variability, myocardial oxygen demand, heart rate, and inflammation. Just as most dietary sodium does not come from the salt shaker, most dietary sugar does not come from the sugar bowl; reducing consumption of added sugars by limiting processed foods containing them, made by corporations would be a good place to start. Indeed, reducing processed-food consumption would be consistent with existing guidelines already in place that misguidedly focus more on the less-consequential white crystals (salt).

Future dietary guidelines should advocate substituting highly refined processed foods (ie, those coming from industrial manufacturing plants) for natural whole foods (ie, those coming from living botanical plants) and be more explicitly restrictive in their allowances for added sugars. The evidence is clear that even moderate doses of added sugar for short durations may cause substantial harm. Box 1 provides important take-aways.

Box 1. Important take-aways.

Sugar may be more meaningfully related to blood pressure than sodium, as suggested by the greater magnitude of effect with dietary manipulation.10 77

Reducing the amount of sodium in processed foods may lead to an increase in their consumption causing a greater prevalence of cardiometabolic disease (figure 1).23

Higher sugar intake significantly increases systolic (6.9mm Hg) and diastolic blood pressure (5.6 mm Hg) in trials of 8 weeks or more in duration.77 This effect is increased to 7.6/6.1 mm Hg, when studies that received funding from the sugar industry are excluded.

Ingesting one 24 ounce soft drink has been shown to cause an average maximum increase in blood pressure of 15/9 mm Hg and heart rate of 9 bpm.81

Those who consume 25% or more calories from added sugar have an almost threefold increased risk of death due to cardiovascular disease.62

Fructose has been shown to stimulate sympathetic tone directly,26 and indirectly by inciting insulin resistance and hyperinsulinaemia.27 45 46

An increase in sympathetic tone from the overconsumption of fructose is one likely mechanism for the sugar's ability to increase heart rate, cardiac output, renal sodium retention, and vascular resistance, all of which may interact to elevate blood pressure and increase myocardial oxygen demand.27 80 82

A high-fructose diet for just 2 weeks not only significantly increased 24 h ambulatory blood pressure (+7/5 mm Hg, p<0.004 and p=0.007, respectively) and increased pulse rate by 8% (4 bpm), but also increased triglycerides, fasting insulin, and homeostatic model assessment (HOMA) index (a measure of insulin resistance and β-cell function).86 Excess fructose intake has also been shown to double the prevalence of the metabolic syndrome.86

Current US per capita intake of added sugars is approximately 2–8 times higher than current recommendations by the American Heart Association (AHA) and WHO.91 92 Considering adolescents specifically, current consumption might be as much as 6–16 times higher.90

Ingestion of sugars, including fructose, in their naturally occurring biological contexts (eg, as whole fruits) is not harmful and is likely beneficial.88 89

Footnotes

Contributors: JJD conducted the literature review, conceived the paper, and drafted the main arguments. SCL helped revise and reorganise the arguments, modified the framing, and recast the introduction and discussion. JJD and SCL cowrote the final paper.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF et al. Correction: actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. JAMA 2005;293:293–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Michaud CM, Murray CJ, Bloom BR. Burden of disease—implications for future research. JAMA 2001;285:535–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Minino AM. Death in the United States, 2009. NCHS Data Brief 2011:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lim SS, Vos T, Flaxman AD et al. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012;380:2224–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2012 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2012;125:e2–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heidenreich PA, Trogdon JG, Khavjou OA et al. Forecasting the future of cardiovascular disease in the United States: a policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2011;123:933–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DiNicolantonio JJ, Niazi AK, Lavie CJ et al. Problems with the American Heart Association Presidential Advisory advocating sodium restriction. Am J Hypertens 2013;26:1201–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DiNicolantonio JJ, Niazi AK, Sadaf R et al. Dietary sodium restriction: take it with a grain of salt. Am J Med 2013;126:951–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DiNicolantonio JJ, O'Keefe JH, Lucan SC. Population-wide sodium reduction: reasons to resist. Mayo Clin Proc 2014;89:426–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Graudal NA, Galloe AM, Garred P. Effects of sodium restriction on blood pressure, renin, aldosterone, catecholamines, cholesterols, and triglyceride: a meta-analysis. JAMA 1998;279:1383–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ekinci EI, Clarke S, Thomas MC et al. Dietary salt intake and mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2011;34:703–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paterna S, Fasullo S, Parrinello G et al. Short-term effects of hypertonic saline solution in acute heart failure and long-term effects of a moderate sodium restriction in patients with compensated heart failure with New York Heart Association class III (Class C) (SMAC-HF Study). Am J Med Sci 2011;342:27–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paterna S, Di Pasquale P, Parrinello G et al. Changes in brain natriuretic peptide levels and bioelectrical impedance measurements after treatment with high-dose furosemide and hypertonic saline solution versus high-dose furosemide alone in refractory congestive heart failure: a double-blind study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005;45:1997–2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Licata G, Di Pasquale P, Parrinello G et al. Effects of high-dose furosemide and small-volume hypertonic saline solution infusion in comparison with a high dose of furosemide as bolus in refractory congestive heart failure: long-term effects. Am Heart J 2003;145:459–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paterna S, Gaspare P, Fasullo S et al. Normal-sodium diet compared with low-sodium diet in compensated congestive heart failure: is sodium an old enemy or a new friend? Clin Sci (Lond) 2008;114:221–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O'Donnell M, Mente A, Rangarajan S et al. Urinary sodium and potassium excretion, mortality, and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med 2014;371:612–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O'Donnell MJ, Yusuf S, Mente A et al. Urinary sodium and potassium excretion and risk of cardiovascular events. JAMA 2011;306:2229–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Vital signs: food categories contributing the most to sodium consumption—United States, 2007–2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2012;61:92–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jalonick M. USA Today 17, June 2014. http://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2014/06/17/fda-reducing-salt/10686357/

- 20.Mente A, O'Donnell MJ, Yusuf S. The population risks of dietary salt excess are exaggerated. Can J Cardiol 2014;30:507–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCarron DA, Geerling JC, Kazaks AG et al. Can dietary sodium intake be modified by public policy? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2009;4:1878–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bernstein AM, Willett WC. Trends in 24-h urinary sodium excretion in the United States, 1957–2003: a systematic review. Am J Clin Nutr 2010;92:1172–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DiNicolantonio JJ, Lucan SC, O'Keefe JH. An unsavory truth: sugar, more than salt, predisposes to hypertension and chronic disease. Am J Cardiol 2014;114:1126–8:In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bray GA, Nielsen SJ, Popkin BM. Consumption of high-fructose corn syrup in beverages may play a role in the epidemic of obesity. Am J Clin Nutr 2004;79:537–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Young JB, Landsberg L. Stimulation of the sympathetic nervous system during sucrose feeding. Nature 1977;269:615–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bunag RD, Tomita T, Sasaki S. Chronic sucrose ingestion induces mild hypertension and tachycardia in rats. Hypertension 1983;5:218–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Facchini FS, Stoohs RA, Reaven GM. Enhanced sympathetic nervous system activity. The linchpin between insulin resistance, hyperinsulinemia, and heart rate. Am J Hypertens 1996;9: 1013–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hwang IS, Ho H, Hoffman BB et al. Fructose-induced insulin resistance and hypertension in rats. Hypertension 1987;10:512–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Preuss HG, Fournier RD. Effects of sucrose ingestion on blood pressure. Life Sci 1982;30:879–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Young JB, Landsberg L. Effect of oral sucrose on blood pressure in the spontaneously hypertensive rat. Metabolism 1981;30:421–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Preuss MB, Preuss HG. The effects of sucrose and sodium on blood pressures in various substrains of Wistar rats. Lab Invest 1980;43:101–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vasdev S, Prabhakaran VM, Whelan M et al. Fructose-induced hypertension, hypertriglyceridemia and elevated cytosolic calcium in rats: prevention by deuterium oxide. Artery 1994;21:124–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bhanot S, McNeill JH, Bryer-Ash M. Vanadyl sulfate prevents fructose-induced hyperinsulinemia and hypertension in rats. Hypertension 1994;23:308–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Farah V, Elased KM, Chen Y et al. Nocturnal hypertension in mice consuming a high fructose diet. Auton Neurosci 2006;130:41–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sanchez-Lozada LG, Tapia E, Bautista-Garcia P et al. Effects of febuxostat on metabolic and renal alterations in rats with fructose-induced metabolic syndrome. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2008;294:F710–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jalal DI, Smits G, Johnson RJ et al. Increased fructose associates with elevated blood pressure. J Am Soc Nephrol 2010;21:1543–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nguyen S, Choi HK, Lustig RH et al. Sugar-sweetened beverages, serum uric acid, and blood pressure in adolescents. J Pediatr 2009;154:807–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kell KP, Cardel MI, Bohan Brown MM et al. Added sugars in the diet are positively associated with diastolic blood pressure and triglycerides in children. Am J Clin Nutr 2014;100:46–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reaven GM, Lithell H, Landsberg L. Hypertension and associated metabolic abnormalities—the role of insulin resistance and the sympathoadrenal system. N Engl J Med 1996;334:374–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Szanto S, Yudkin J. Dietary sucrose and the behaviour of blood platelets. Proc Nutr Soc 1970;29:Suppl:3A. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reiser S, Bohn E, Hallfrisch J et al. Serum insulin and glucose in hyperinsulinemic subjects fed three different levels of sucrose. Am J Clin Nutr 1981;34:2348–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Szanto S, Yudkin J. Insulin and atheroma. Lancet 1969;1:1211–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Daly ME, Vale C, Walker M et al. Dietary carbohydrates and insulin sensitivity: a review of the evidence and clinical implications. Am J Clin Nutr 1997;66:1072–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reaven GM. Insulin resistance, hyperinsulinemia, and hypertriglyceridemia in the etiology and clinical course of hypertension. Am J Med 1991;90:7s–12s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reiser S, Handler HB, Gardner LB et al. Isocaloric exchange of dietary starch and sucrose in humans. II. Effect on fasting blood insulin, glucose, and glucagon and on insulin and glucose response to a sucrose load. Am J Clin Nutr 1979;32:2206–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hallfrisch J, Ellwood KC, Michaelis OE 4th et al. Effects of dietary fructose on plasma glucose and hormone responses in normal and hyperinsulinemic men. J Nutr 1983;113:1819–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bruckdorfer KR, Kang SS, Yudkin J. Insulin sensitivity of adipose tissue of rats fed with various carbohydrates. Proc Nutr Soc 1974;33:4a–5a. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Landsberg L. Insulin and the sympathetic nervous system in the pathophysiology of hypertension. Blood Press Suppl 1996;1:25–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Landsberg L. Pathophysiology of obesity-related hypertension: role of insulin and the sympathetic nervous system. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 1994;23(Suppl 1):S1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Canale MP, Manca di Villahermosa S, Martino G et al. Obesity-related metabolic syndrome: mechanisms of sympathetic overactivity. Int J Endocrinol 2013;2013:865965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ferrannini E, Buzzigoli G, Bonadonna R et al. Insulin resistance in essential hypertension. N Engl J Med 1987;317:350–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shen DC, Shieh SM, Fuh MM et al. Resistance to insulin-stimulated-glucose uptake in patients with hypertension. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1988;66:580–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stanhope KL, Schwarz JM, Keim NL et al. Consuming fructose-sweetened, not glucose-sweetened, beverages increases visceral adiposity and lipids and decreases insulin sensitivity in overweight/obese humans. J Clin Invest 2009;119:1322–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vasdev S, Stuckless J. Role of methylglyoxal in essential hypertension. Int J Angiol 2010;19:e58–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pell S, D'Alonzo CA. Some aspects of hypertension in diabetes mellitus. JAMA 1967;202:104–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Christlieb AR. Diabetes and hypertensive vascular disease. Mechanisms and treatment. Am J Cardiol 1973;32:592–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zavaroni I, Mazza S, Dall'Aglio E et al. Prevalence of hyperinsulinaemia in patients with high blood pressure. J Intern Med 1992;231:235–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pollare T, Lithell H, Berne C. Insulin resistance is a characteristic feature of primary hypertension independent of obesity. Metabolism 1990;39:167–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cohen AM, Teitelbaum A, Balogh M et al. Effect of interchanging bread and sucrose as main source of carbohydrate in a low fat diet on the glucose tolerance curve of healthy volunteer subjects. Am J Clin Nutr 1966;19:59–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yudkin J. Sugar and disease. Nature 1972;239:197–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Basu S, Yoffe P, Hills N et al. The relationship of sugar to population-level diabetes prevalence: an econometric analysis of repeated cross-sectional data. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e57873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yang Q, Zhang Z, Gregg EW et al. Added sugar intake and cardiovascular diseases mortality among US adults. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:516–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Marriott BP, Olsho L, Hadden L et al. Intake of added sugars and selected nutrients in the United States, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2003–2006. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2010;50:228–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Brown IJ, Stamler J, Van Horn L et al. Sugar-sweetened beverage, sugar intake of individuals, and their blood pressure: international study of macro/micronutrients and blood pressure. Hypertension 2011;57:695–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Malik AH, Akram Y, Shetty S et al. Impact of sugar-sweetened beverages on blood pressure. Am J Cardiol 2014;113:1574–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Walker RW, Dumke KA, Goran MI. Fructose content in popular beverages made with and without high fructose corn syrup. Nutrition 2014;30:928–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ventura EE, Davis JN, Goran MI. Sugar content of popular sweetened beverages based on objective laboratory analysis: focus on fructose content. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md) 2011;19:868–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Malik VS, Popkin BM, Bray GA et al. Sugar-sweetened beverages and risk of metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care 2010;33:2477–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schulze MB, Manson JE, Ludwig DS et al. Sugar-sweetened beverages, weight gain, and incidence of type 2 diabetes in young and middle-aged women. JAMA 2004;292:927–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fung TT, Malik V, Rexrode KM et al. Sweetened beverage consumption and risk of coronary heart disease in women. Am J Clin Nutr 2009;89:1037–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Larsson SC, Akesson A, Wolk A. Sweetened beverage consumption is associated with increased risk of stroke in women and men. J Nutr 2014;144:856–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Choi HK, Willett W, Curhan G. Fructose-rich beverages and risk of gout in women. JAMA 2010;304:2270–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Malik VS, Schulze MB, Hu FB. Intake of sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain: a systematic review. Am J Clin Nutr 2006;84:274–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ferraro PM, Taylor EN, Gambaro G et al. Soda and other beverages and the risk of kidney stones. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2013;8:1389–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Singh GM, Micha R, Katibzadeh S et al. Mortality due to sugar sweetened beverage consumption: a global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment. Circulation 2013;127:AMP22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Israel KD, Michaelis OE 4th, Reiser S et al. Serum uric acid, inorganic phosphorus, and glutamic-oxalacetic transaminase and blood pressure in carbohydrate-sensitive adults consuming three different levels of sucrose. Ann Nutr Metab 1983;27: 425–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Te Morenga LA, Howatson AJ, Jones RM et al. Dietary sugars and cardiometabolic risk: systematic review and meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials of the effects on blood pressure and lipids. Am J Clin Nutr 2014;100:65–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Raben A, Vasilaras TH, Moller AC et al. Sucrose compared with artificial sweeteners: different effects on ad libitum food intake and body weight after 10 wk of supplementation in overweight subjects. Am J Clin Nutr 2002;76:721–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rebello T, Hodges RE, Smith JL. Short-term effects of various sugars on antinatriuresis and blood pressure changes in normotensive young men. Am J Clin Nutr 1983;38: 84–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rumessen JJ, Gudmand-Hoyer E. Absorption capacity of fructose in healthy adults. Comparison with sucrose and its constituent monosaccharides. Gut 1986;27:1161–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Le MT, Frye RF, Rivard CJ et al. Effects of high-fructose corn syrup and sucrose on the pharmacokinetics of fructose and acute metabolic and hemodynamic responses in healthy subjects. Metabolism 2012;61:641–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Brown CM, Dulloo AG, Yepuri G et al. Fructose ingestion acutely elevates blood pressure in healthy young humans. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2008;294:R730–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hata J, Arima H, Rothwell PM et al. Effects of visit-to-visit variability in systolic blood pressure on macrovascular and microvascular complications in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: the ADVANCE trial. Circulation 2013;128:1325–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Webb AJ, Rothwell PM. Physiological correlates of beat-to-beat, ambulatory, and day-to-day home blood pressure variability after transient ischemic attack or minor stroke. Stroke 2014;45:533–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Parati G, Pomidossi G, Albini F et al. Relationship of 24-hour blood pressure mean and variability to severity of target-organ damage in hypertension. J Hypertens 1987;5:93–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Perez-Pozo SE, Schold J, Nakagawa T et al. Excessive fructose intake induces the features of metabolic syndrome in healthy adult men: role of uric acid in the hypertensive response. Int J Obes (Lond) 2010;34:454–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Brymora A, Flisinski M, Johnson RJ et al. Low-fructose diet lowers blood pressure and inflammation in patients with chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2012;27:608–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Meyer BJ, de Bruin EJ, Du Plessis DG et al. Some biochemical effects of a mainly fruit diet in man. S Afr Med J 1971;45: 253–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Madero M, Arriaga JC, Jalal D et al. The effect of two energy-restricted diets, a low-fructose diet versus a moderate natural fructose diet, on weight loss and metabolic syndrome parameters: a randomized controlled trial. Metabolism 2011;60:1551–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Yudkin J. Pure, white and deadly. Penguin Books, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Strom S. U.S. Cuts Estimate of Sugar Intake. The New York Times 26 October2012.

- 92.Cordain L, Eades MR, Eades MD. Hyperinsulinemic diseases of civilization: more than just Syndrome X. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol 2003;136:95–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.http://www.sugarstacks.com (accessed 27 Aug 2014).

- 94.Westman EC. Is dietary carbohydrate essential for human nutrition? Am J Clin Nutr 2002;75:951–3; author reply 3–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Johnson RK, Appel LJ, Brands M et al. Dietary sugars intake and cardiovascular health: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2009;120:1011–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Malnik E. World Health Organisation advises halving sugar intake. The Telegraph March2014.

- 97.Trumbo P, Schlicker S, Yates AA et al. Dietary reference intakes for energy, carbohydrate, fiber, fat, fatty acids, cholesterol, protein and amino acids. J Am Diet Assoc 2002;102:1621–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Eckel RH, Jakicic JM, Ard JD et al. 2013 AHA/ACC Guideline on Lifestyle Management to Reduce Cardiovascular Risk: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;63(25 Pt B):2960–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Lucan SC. Attempting to reduce sodium intake might do harm and distract from a greater enemy. Am J Public Health 2013;103:e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]