Abstract

A 43 -year-old man was treated with pazopanib for metastatic renal cell carcinoma (RCC) with imaging studies suggesting a partial response to treatment. However, the patient presented numerous times with severe testicular pain and gradually increasing priapism. He underwent an inguinal orchidectomy for symptom control. Histopathology confirmed invasion of the cord and tunica vaginalis with metastatic RCC. Further CT of the abdomen and pelvis suggested non-progression of the disease. The patient continued to develop priapism for several weeks before imaging studies confirmed disease progression; a month later the patient died. Genital involvement in metastatic RCC is unusual but should alert clinicians to the possibility of disease progression.

Background

Scrotal pain and priapism are well-documented signs of advanced disease in prostate and bladder cancer, but little is known about their involvement in advanced renal cell carcinoma (RCC). This case demonstrated that there may be signs of disease progression before progression is apparent on CT and/or MRI. Early information of disease progression may allow oncologists to modify treatment to improve quality of life and survival.

Case presentation

A 40-year-old man presented with hypercalcaemia (3.8 mmol/L) and a persistent cough. Investigation with a CT chest revealed small focal abnormalities in the lungs with multiple liver abnormalities measuring up to 4.5 cm (figure 1). A CT of the abdomen showed a 10.8 cm×7.9 cm×7.3 cm mass in the upper pole of the right kidney consistent with metastatic RCC (figure 2). Mozer score placed the patient in the intermediate risk category on account of no previous nephrectomy and hypercalcaemia. The hypercalcaemia was treated and a renal biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of metastatic RCC. The patient was started on pazopanib, a multikinase inhibitor, as he was not considered medically well for an immediate cytoreductive nephrectomy.

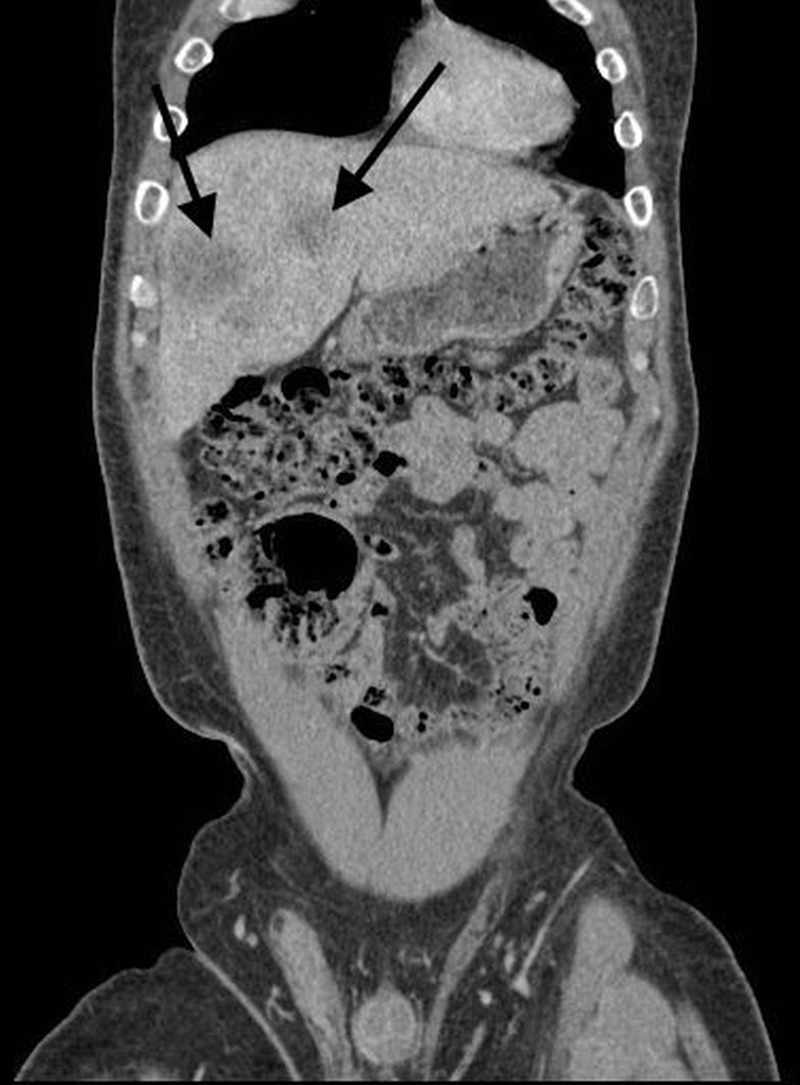

Figure 1.

Coronal reconstruction of CT: low attenuation lesions in the liver (black arrows), known to be metastatic renal cell carcinoma.

Figure 2.

Axial CT showing right-sided renal tumour (black arrow).

The patient improved; the tumour underwent a partial response and the hypercalcaemia resolved. Four months later a right-sided open cytoreductive nephrectomy was carried out. The patient made a good recovery. A month after his nephrectomy, he returned to the clinic with a painful, swollen right testicle. The hydrocoele was aspirated but the pain failed to settle. A repeat ultrasound revealed an abnormally thickened right spermatic cord. A right-sided inguinal orchidectomy was performed for symptom control. The pathology of this confirmed a tumour (metastatic clear cell RCC).

CT of the chest, abdomen and pelvis (CAP) were repeated, which showed no increase in tumour burden, and the treatment with pazopanib continued. One month later the patient presented with slowly increasing painful induration of the penis. Ultrasound and MRI of the penis were performed, which showed normal penile anatomy and no focal lesions. Instead, on T2-weighted MRI, the corpora displayed reduced signal throughout (figure 3), which raised the possibility of diffuse corporal infiltration secondary to metastatic RCC. The patient was not well enough for surgical treatment, so the priapism was treated symptomatically with analgesia while medical management of the underlying disease continued.

Figure 3.

T2-weighted axial MRI demonstrating reduced signal throughout the corpora, consistent with tumour infiltration (white arrows). Under normal conditions, the corpora return a high signal on T2-weighted MRI.

Outcome and follow-up

CT CAP was repeated, which showed increase in size of hepatic and pulmonary lesions (figure 4) as well as lymphadenopathy. Pazopanib was stopped and treatment with everolimus, an mTOR inhibitor, was initiated. Unfortunately, the patient continued to deteriorate and died of his disease 3 months later.

Figure 4.

Axial CT through liver demonstrating increase in the size of the liver metastases (black arrows) due to disease progression.

Discussion

Priapism is defined as a penile erection, which is prolonged in the absence of sexual stimuli. There are many causes found in the literature, however, the most significant could be due to ischaemia (peripheral vascular disease) or an obstruction of the venous drainage from the corpora cavernosa.

Other medical causes have also been identified, such as α agonists, vasocative agents and antipsychotics. A literature search has shown that an increased viscosity of blood may also be a cause of priapism, for example, polycythaemia, haematological malignancy or sickle cell anaemia.1

Metastatic spread to the penis is extremely rare, with around 150 cases reported to date.2 The most common primaries tend to be the prostate and bladder but others have also been reported, such as kidneys, ureter, bladder, testes, lung, stomach, bone and hepatobiliary.3

The penis has a rich blood supply, (mainly the dorsal artery of the penis). It is assumed that spread occurs via retrograde venous (batson plexus), lymphatic route, arterial spread, direct extension and possibly implantation of instrumentation.4 The pathophysiology of malignant priapism stems from infiltrating cells occluding the venous drainage of the cavernosus sinuses and hence becoming distended, resulting in a painful erection.5

The diagnosis of penile metastatic spread is usually made through imaging such as CT or MRI. Although MRI is an excellent modality for soft tissue definition, it is not superior to clinical examination for local staging. Penile MRI is performed with a T2-weighted sequence, although T1-weighted images may be used for the detection of haemorrhage and thrombosis within the corpora. For imaging the cavernosal vessels, dynamic contrast-enhanced sequences can be used. For assessment of cavernosal viability in priapism, comparison should be made before and 10 min after contrast. Contrast enhancement for staging tumours is usually not helpful.6 Definitive diagnosis of penile metastatic spread can be made intraoperatively with the use of frozen sections.

Patients who present with penile invasion are usually unwell before the diagnosis is made. Penile invasion carries a poor prognosis and treatment is usually palliative. There may be cases where local excision, partial/total penectomy or even radiotherapy is proposed, however, the mainstay tends to be focusing on symptom management.

Clinicians need to be aware of the potential spread of urogenital metastasis to atypical sites. Early intervention is key for reducing morbidity and mortality, and even with the use of multikinase inhibitors, the prognosis is still very poor.

Learning points.

Testicular pain and priapism can be complications of malignant disease including renal cell carcinoma.

The disease may be of haematological origin, or result from local infiltration.

Acute scrotum and priapism are urological emergencies and should be urgently assessed and managed.

Ultrasound sonography and MRI may aid diagnosis.

Be alert to possibility of disease progression.

Footnotes

Contributors: KP and BL compiled the case report, with the help of JP overlooking the process. KH had the consent form signed by the patient and helped with editing of the report.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Broderick GA. Priapism. In: Wein AJ, ed. Campbell-Walsh urology. 10th edn Philadelphia, PA: Saunders, 2011:749–69, Ch 25. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abeshouse BS, Abeshouse GA. Metastatic tumors of the penis: a review of the literature and a report of two cases. J Urol 1961;86:99–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chaux A, Amin M, Cubilla AL et al. Metastatic tumors to the penis: a report of 17 cases and review of the literature. Int J Surg Pathol 2010;19:597–606. 10.1177/1066896909350468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cherian J, Rajan S, Thiwaini A et al. Secondary penile tumors revisited. Int Semin Surg Oncol 2006;3:33 10.1186/1477-7800-3-33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rajarubendra N, Pook D, Frydenberg M et al. Rare synchronous metastases of renal cell carcinoma. Urol Ann 2014;6:157–8. 10.4103/0974-7796.130652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kirkham A. MRI of the penis. Br J Radiol 2012;85:S86–93. 10.1259/bjr/63301362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]