Abstract

The search for clinical outcome predictors for schizophrenia is as old as the field of psychiatry. However, despite a wealth of large, longitudinal studies into prognostic factors, only very few clinically useful outcome predictors have been identified. The goal of future treatment is to either affect modifiable risk factors, or use nonmodifiable factors to parse patients into therapeutically meaningful subgroups. Most clinical outcome predictors are nonspecific and/or nonmodifiable. Nonmodifiable predictors for poor odds of remission include male sex, younger age at disease onset, poor premorbid adjustment, and severe baseline psychopathology. Modifiable risk factors for poor therapeutic outcomes that clinicians can act upon include longer duration of untreated illness, nonadherence to antipsychotics, comorbidities (especially substance-use disorders), lack of early antipsychotic response, and lack of improvement with non-clozapine antipsychotics, predicting clozapine response. It is hoped that this limited capacity for prediction will improve as pathophysiological understanding increases and/or new treatments for specific aspects of schizophrenia become available.

Keywords: schizophrenia, psychosis, response, remission, predictor, marker, association

Abstract

La búsqueda de predictores de resultado clínico en la esquizofrenia es tan antigua como la psíquiatría. Sin embargo, a pesar de una gran cantídad de estudios longitudinales sobre los factores pronóstico, solo se han identificado unos pocos predíctores de resultado con utilidad clínica. El objetivo de las terapias a futuro es influir sobre los factores de riesgo modíficables, o bien emplear los factores inmodíficables para analizar a los pacientes en subgrupos terapéuticamente signíficativos. La mayor parte de los predictores de resultado clínico son inespecíficos ylo inmodíficables. Cuando hay una baja probabílidad de remisión los predictores inmodíficables incluyen al sexo masculíno, la menor edad de aparición de la enfermedad, un pobre ajuste premórbido y una grave psicopatología basal. Cuando hay pobres resultados terapéuticos los factores de riesgo modíficables sobre los cuales pueden actuar los clínicos incluyen la mayor duración de la enfermedad sín tratamiento, la falta de adherencía a los antipsicóticos, la comorbilidad (especialmente el abuso de sustancias), la falta de respuesta ínicial a los antipsicóticos y la ausencia de mejoría con antipsicóticos distintos de la clozapina, lo que puede predecír una respuesta a esta última. Se espera que esta capacidad límitada de predíccíón aumente en la medída que sea mayor la comprensión fisiopatológica ylo se disponga de nuevos tratamientos para aspectos específicos de la esquizofrenia.

Abstract

La recherche de facteurs de prédiction des résultats cliniques dans la schizophrénie est aussi ancienne que la psychiatrie elle-meme. Néanmoins, malgré de nombreuses grandes études longitudinales sur les facteurs pronostiques, très peu de ces facteurs utiles cliniquement ont été identifiés. Le but d'un traitement futur est soit de changer les facteurs de risque modifiables ou d'utiliser des facteurs non modifiables pour regrouper les patients dans des sous-groupes déterminants sur le plan thérapeutique. La plupart des facteurs de prédiction des résultats cliniques sont non spécifiques et/ou non modifiables. Le sexe masculin, un plus jeune âge au début de la maladie, un mauvais ajustement prémorbide et une pathologie psychiatrique sévère dès le début font partie des facteurs de prédiction non modifiables pour des chances de rémission médiocres. Une durée plus longue de maladie non traitée, une absence d'observance des antipsychotiques, des comorbidités (surtout l'usage de substances illicites), une absence de réponse précoce aux antipsychotiques et l'absence d'amélioration avec les antipsychotiques non-clozapiniques prédisant la réponse à la clozapine font partie des facteurs de risque modifiables de résultats thérapeutiques médiocres sur lesquels les médecins peuvent agir. Il faut espérer que cette faible capacité prédictive s'améliorera avec une meilleure compréhension physiopathologique et/ou le développement de traitements visant des aspects spécifiques de la schizophrénie.

Introduction

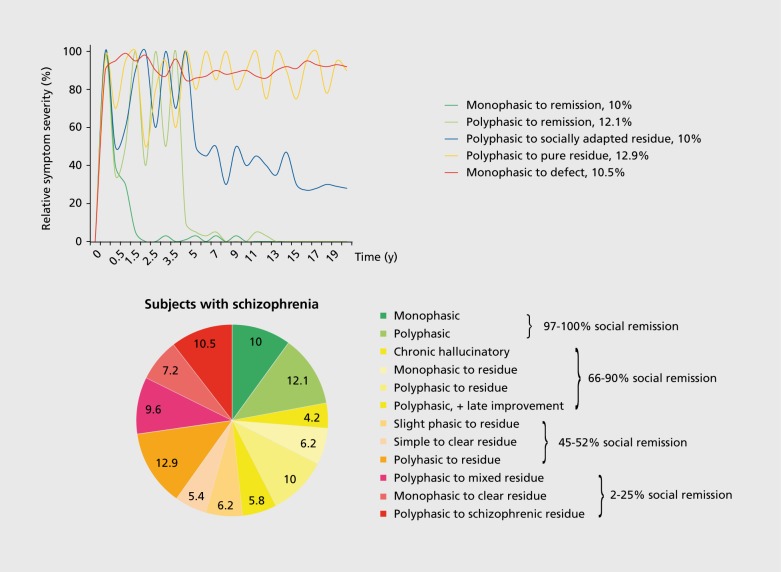

“No symptoms or syndromes at the time of onset could be used to predict, with any certainty, whatever the differentiation between malignant or benign process [...].” Huber and colleagues1 published this poignant notion 40 years ago in the context of a meticulous longitudinal study of 502 patients with schizophrenia, 75% of whom had been followed for 22 years. Despite having identified twelve major classes of courses of illness that to this date are still relevant (Figure 1A, B). the authors revert to a rather nihilistic statement regarding the possibility of predicting course and illness outcome for an individual patient. Since then, numerous additional longitudinal studies in schizophrenia have been conducted and reviewed without reaching consensus about consistent patterns of illness courses in schizophrenia beyond the notion of high heterogeneity and a high frequency of unfavorable outcomes.2-10 Nevertheless, several robust factors associated with poorer long-term outcome emerged from these studies: poor premorbid adjustment, male sex, earlier onset of disease, longer duration of the illness, and/or longer duration of untreated psychosis (DUP).

Figure 1. (A) Five most common long-term disease courses (>10%) in schizophrenia during 20-year follow-up.1 Schematic display of long-term courses of disease 502 subjects with baseline diagnosis of schizophrenia during 20-year follow-up.1 Colored lines reflect the relative severity of schizophrenia symptoms in the five most frequent course types. (B) Relative frequencies of all twelve disease course types1 in schizophrenia during 20-year follow-up, with rates of social remission.

Using chronic patient cohorts to predict outcomes is complicated by factors that both increase heterogeneity and decrease generalizability: (i) Chronic patients have widely varying illness duration and prior treatment exposure; (ii) they are also self-selected for poorer outcome11; (iii) information about premorbid and earlier illness phases are likely less reliable; and (iv) diagnostic classifications may change during long-term follow-up. First episode (FE) schizophrenia samples share at least a common starting point in their illness course, and are thus more suited to studying predictors of therapeutic outcomes.

Reviews of outcomes in FE psychosis concluded that up to 22% of subjects may recover within the first 5 years without further relapses.4,6 However, in subjects meeting full criteria for schizophrenia as opposed to other psychoses, relapse rates reach 80% to 85% during the first 5 years of illness.6,10,12 Even when limiting their overview to 21 studies with consistent criteria for schizophrenia (DSM-III DSM-III-R, DSM-IV, ICD-10 schizophreniform, or schizoaffective disorders), wide variations were observed regarding remission (7% to 52%) or having a “chronic” course (34% to 57%),10 characterized by residual symptoms and/or relapses.

Ultra-long-term studies of schizophrenia are not only limited by feasibility aspects, but also by continued discussions about diagnostic boundaries,13 lack of a neurobiological definition of schizophrenia,14 drop-outs that are not at random, and by limited knowledge of the untreated/natural disease course. Therefore, attention has shifted to studies aiming at understanding predictors of treatment response, remission, recovery and relapse, as markers of short- to mid-term prognosis (up to 5 years). Thus, even if we will not be able to identify reliable, modifiable, or outcome-relevant predictors of long-term results, we may be able to identify predictors for each phase of the disease course. Knowledge of prognostic factors may aid in identifying patient and treatment factors, and the interaction between the two that would help select treatments that are more likely to succeed, thereby avoiding multiple, unnecessary switches or treatment trials. If reliable predictors of response to different individual treatments could be found, this would enable stratified or individualized treatment in specific patient subgroups that likely differ biologically, leading to the observed heterogeneity of therapeutic response.15 Since relapses are a major source of individual suffering and societal cost of the illness, predictors of relapse have rightfully received attention.16-18 Although a recent meta-analysis identified medication nonadherence, depression, and substance use as the top three factors associated with relapse,17 except for the unequivocal role of nonadherence, results for all other predictors were heterogeneous and it has been emphasized that individual prediction of imminent relapse remains elusive.18 In this review, we have focused on response and remission (see definitions below), as relapse is not simply the inverse of reaching each of these steps. Furthermore, recovery, a concept that combines symptomatic remission with achieving certain functional levels,19 has received increasing attention.20 However, here we do not focus on recovery, as functional outcomes depend on psychosocial environment and interventions more than on current antipsychotic treatment, which can only provide a basis for additional nonpharmacologic interventions that can help patients achieve psychosocial, educational, and vocational goals. Although, ultimately, it will be necessary to combine clinical with neurobiological markers of diagnosis and outcomes, the scope of this review is limited to clinical predictors of therapeutic response and remission. Since, as mentioned, FE samples have advantages for identifying more generalizable and reliable correlates of short- and medium-term outcomes, we focus on FE studies wherever possible.

Methods

Literature for this review was identified by searching PubMed, using the terms <schizophrenia> or <psychosis> and <outcome> or <response> or <remission>, and by manual searches of reference lists of relevant publications. Due to the wealth of outcome studies in schizophrenia that used very heterogeneous designs and outcome definitions, we refrained from a systematic review and meta-analysis. Instead, we gave weight to the most recent reviews,6,9 updating the evidence by relevant studies published since 2006. Due to the methodological limitations discussed above, we focused on FE psychosis, using additional data from work in chronic schizophrenia for specific aspects, including treatmentrefractory schizophrenia and areas with relevant differences between FE and multi-episode schizophrenia. Moreover, to avoid the methodological limitations of ultra-long-term studies,10 we focused on studies with up to 5 years' follow-up.

Definitions of key elements of the outcome pathway

The American Psychiatric Association's Practice Guideline for Schizophrenia treatment21 defines phases of response to treatment as taking 1 to 2 years in order to move from the acute phase, through the stabilization and stable phase, to the recovery period, if not interrupted by relapse. Dissecting this dynamic process into defined sub-periods is artificial, but necessary to consider manageable, informative time frames. However, the terms response, remission, recovery, and even relapse have been used inconsistently. Thresholds and operational definitions for these illness phases have been reviewed and discussed, but consensus for all terms is missing.22 In addition to the physicians' perspective, recent work also highlighted the importance of the patients' perspective, adding subjective well-being and quality of life as important outcome targets.23 Although these subjective and functional outcome dimensions are highly important, pragmatic reasons limit the present review to predictors of response and remission.

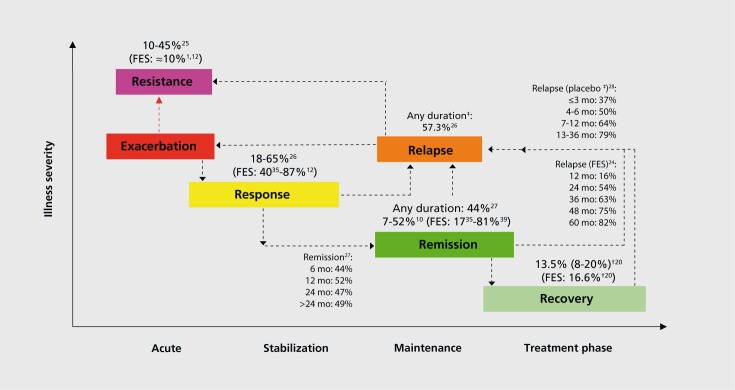

Figure 2 summarizes the main illness phases with estimates of the frequency of patients with schizophrenia being in or transitioning to these respective illness phases,1,10,12,20,35,39,24-28 recognizing that individual samples, definitions, and time frames differed considerably.

Figure 2. Disease phases in schizophrenia, including average frequencies of patients transitioning to each of these treatment phases.1,10,12,20,35,39,24-28 FES, first-episode schizophrenia; t, median (interquartile range); #, in antipsychotic discontinuation studies.

Response is a relative term, defining a clinically significant improvement of a subject's global psychopathology, irrespective of whether or not the subject continues to have specific symptoms. In clinical trials, thresholds for response have sometimes been arbitrarily defined.22 Although clear agreement regarding accepted cutoffs is missing, a proportion of symptom reduction is generally defined. Treatment response is a key determinant of subsequent outcome, as it is an essential precondition for remission and recovery,29 being closely related to treatment continuation.30,31 However, using cutoffs omits informative value of continuous data, reducing the variable spectrum of individual illness pathways to a binary result. Using equipercentile linking of percentage improvement in the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS)/Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) with improvement in the Clinical Global Impressions improvement (CGI-I) scale, Levine and colleagues32 showed that a 20% to 25% reduction of the BPRS/PANSS baseline score corresponded to minimal improvement on the CGI-I, whereas a 40% to 50% reduction corresponded to “much improved.” Since many acutely ill patients with schizophrenia often respond well to therapy, it was concluded that for acutely ill patients the 50% cutoff would be a clinically meaningful criterion. However, in chronic or treatment-resistant patients, even a small improvement might represent a clinically significant effect, justifying the use of the 20% to 25% cutoff in treatment-refractory patients. Therefore, the authors advocate for reporting results for multiple thresholds in the same study in order to display the entire range of response groups.32

Remission is an absolute term defined as the sustained absence of significant (but not necessarily all) clinical signs and symptoms, using various thresholds for remaining symptoms prior to the consensus definition by the Schizophrenia work group.28 This workgroup defined “remission” by a rating of key positive and negative symptoms at a level of “mild” or less, which needs to be maintained for ≥6 months. Despite existing consensus criteria for remission,33 this definition is currently not used consistently, but the term remission is often used as a cross-sectional criterion for the presence of mild symptoms (Table I).

Table I. Proposed items for remission criteria as defined by the Remission in Schizophrenia Working Group.28 aFor symptomatic remission, maintenance over a 6-month period of simultaneous ratings of mild or less on all items is required. Rating scale items are listed by item number. bUse of BPRS criteria may be complemented by use of the SANS criteria for evaluating overall remission. The PANSS scale is the simplest instrument on which a definition of symptom remission can be practically based. DSM-IV, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition.

| Scale for Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS) and Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) items | Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) items | Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) items | |||||

| Dimension of psychopathology | DSM-IV criterion | Criterion | Global Ratig item number | Criterion | Item number | Criterion | Item number |

| Psychoticism (reality, distortion) | Delusions | Delusions (SAPS) | 20 | Delsions | P1 | Grandiosity | 8 |

| Suspiciousness | 11 | ||||||

| Unusual thought content | G9 | Unsual thought content | 15 | ||||

| Hallucinations | Hallucinations (SAPS) | 7 | Hallucinatory behavior | P3 | Hallucinatory behavior | 12 | |

| Disorganization | Disorganized speech | Positive formal thought disorder (SAPS) | 34 | Conceptual disorganization | P2 | Conceptual disorganization | 4 |

| Grossly disorganized or catatonic behavior | Bizarre behavior (SAPS) | 25 | Mannerisms/posturing | G5 | Mannerisms/posturing | 7 | |

| Negative symptoms (psychomotor poverty) | Negative symptoms | Affective flattening (SANS) | 7 | Blunted effect | N1 | Blunted affect | 16 |

| Avolition-apathy (SANS) | 17 | Social withdrawal | N4 | No clearly related symptom | |||

| Anhedonia-asociality (SANS) | 22 | ||||||

| Alogia (SANS) | 13 | Lack of spontaneity | N6 | No clearly related symptom |

To interpret the clinical remission criteria within the context of the patient's life, outcome studies also studied functional/psychosocial remission, and both terms have been used to define favorable outcome separately or in combination. The earlier longitudinal outcome studies stratified subgroups according to functional outcomes, and considered being employed at least part-time at or closely below the premorbid occupational level a favorable outcome. For the purpose of this paper, we used the term “sustained remission” whenever the workgroup criteria34 were used correctly, requiring the period criterion of 6 months; when the time criterion was dropped, we used the term “cross-sectional remission.” Recovery is an outcome domain that combines symptomatic remission with a minimum of self-care, social and education/vocational functioning that are all sustained for at least 2 years.19,20,22

Results

Across FE studies of schizophrenia-spectrum disorders, response rates varied from 40% at 16 weeks of antipsychotic treatment35 to 81%36 and even 87%12 at 1 year, with a cluster around 50% within the first year of treatment29,35'38 (see Table II29-65 for frequencies and predictors by study). Remission rates vary more, even in studies using standardized remission criteria,33 with rates as low as 17% for haloperidol in the European First-Episode Schizophrenia study35 to rates as high as 81% in a Chinese First-Episode study,39 with several studies ranging around 35% to 50%29,40,41,42 (Table II).

Table II. Studies reporting on response or remission and its predictors in patients with first episode (FE) psychosis (2006-06/2014). BRP, brief reactive psychosis; SCZ, schizophrenia; SADS-C +PD, Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia Change Version with psychosis and disorganization items; PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; SAPS, Scale for the assessment of positive symptoms; SANS, Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms; HEN, High Royds Evaluation of Negativity Scale; BPRS, Brief psychiatric rating scale; DUP, Duration of untreated Psychosis; GAF, Global Assessment of Functioning Scale; CGI, Clinical Global Impression.

| Study | Outcome | Cohort measures | Outcome rates - baseline/clinical predictors for outcome as reported by the study |

| Addington & Addington 2008.40 | Sustained remission | 240 FE SCZ- spectrum disorder or other psychotic disorder PANSS; 6 monthly up to 36 (mean 26.4) months | 36.7% achieved sustained remission. Additional 20.4% achieved cross-sectional remission at some point. Nonremitters (23.3%): lower baseline GAF, worse insight, higher positive and/or negative symptom score, reduced social functioning, lower premorbid functioning, longer DUP |

| Agid 201143 | Response CGI-I = 1-2 and/ or BPRS Thought Disorder subscale score ≤ 6 | 244 subjects with FE SCZ or schizoaffective disorder, followed through up to 3 treatment trials (each 12 weeks) to determine treatment rates in subsequent treatment trials | 1st trial response rate: 74.5% (olanzapine: 82.1%; risperidone: 66.3%; P<0.01); 2nd trial, response rate 16.6% (olanzapine: 25.7%; risperidone: 4.0%). 3.trial; response rate: 75.0% (clozapine) |

| Albert 201144 | Recovery (symptomatic remission + occupational + social functioning) | 255 FE psychosis; 5 years | 15.7% recovery, but <50% of these had achieved recovery within 2 years. 29.8% professionally occupied. Predictors of recovery: female, higher age, good premorbid function, stable social environment |

| Boter 200935 | Response: ≥ 50% PANSS reduction Sustained remission | 498 FE SCZ (EUFEST) schizophreniform, or schizoaffective disorder; PANSS 12 months follow-up | Response/ remission rates varied with antipsychotic from 37%/17% (haloperidol) to 67%/40% (amisulpride or olanzapine). Predictors for response: adherence, more severe baseline psychopathology, treatment with amisulpride. Predictors for remission: adherence, treatment with amisul pride or olanzapine, no current substance use disorder |

| Chang 201145 | Intermediate-term Outcome | 93 SCZ, schizophreniform, schizoaffective; SANS, HEN f. negative symptoms; 3 years follow-up | Comparison of subjects with/without persistent primary negative symptoms: clinical and cognitive baseline characteristics did not predict PPN at year 3 |

| Chang 2012.46 | Sustained remission | 700 FE psychosis SANS, 3 years | At 3 year end point 58.8% symptomatic remission. Logistic regression for symptomatic remission: female, older age at disease onset, shorter DUP and early treatment response |

| Crespo-Facorro 200747 | Response = ≥ 40% BPRS reduction | 172 subjects with FE SCZ spectrum; BPRS. SAPS, SANS, CGI; 6 weeks | 57.8% response. Predictors of poor response: diagnosis of SCZ, young age of onset, poor premorbid adolescent adjustment, lower BL BPRS |

| Crespo-Facorro 201336 | Response at 6 weeks (≥ 40% BPRS reduction + CGI total score of ≤ 4) | 375 FE BRP, SCZ, schizophreniform disorder, schizoaffective disorder: BPRS. SAPS, SANS, CGI weekly. 6 weeks | 53.3% response rate. Predictors of poor response: lower severity of BL symptoms, diagnosis of SCZ; longer DUP, poorer premorbid adjustment, family history of psychosis, hospitalization |

| Derks 201048 | Sustained remission | 498 subjects with FE SCZ, schizophreniform, schizoaffective; 12 months PANSS | 59% sustained remission, 77% cross-sectional remission. Predictive early response (CGI mild) at week 2, but improved prediction based on 6-week data PPV (0.73), NPV (0.61) Lower odds for remission: male, BL akathisia, no early response, no remission at week 4 |

| Diaz 201349 | Sustained remission | 174 FE, BRP, schizophreniform disorder, SCZ, schizoaffective disorder, or psychosis NOS; BPRS, SAPS, SANS; Cognitive Measures; 1 year | 31% sustained remission at 1 year. Predictors of sustained remission: shorter DUP, lower BL negative symptoms, and complete primary education. Model predicted non-remission by 89.9%. Univariate characteristics of non-response: male, SCZ, single status, lower primary educational level |

| Emsley 2006.41 | Sustained remission | 57 FE SCZ, schizophreniform or schizoaffective disorder PANSS; 24 months | 70% cross-sectional remission. 33% sustained remission. Multivariate model predicting 86% of nonremitters: presence of neurologic soft signs, DUP>1 year, marital status, and high PANSS excited/hostility factor score at baseline. Nonremitters at 2 years had lower % PANSS reduction at week 6 |

| Emsley 200742 | Sustained remission | 462 SCZ, schizophreniform or schizoaffective disorder PANSS; CGI; 2-4 years | 70% cross-sectional remission criterion at some point; 23.6% sustained remission. Mean time until first remission 153 ± 173 days. Independent predictor of sustained remission: DUP 33% with <391 days DUP remitted, 18% with longer DUPs remitted |

| Gäbel 201450 | Sustained remission Cross-sectional remission | 166 subjects FE SCZ, past acute treatment period. GAF, PANSS (all at the beginning of the maintenance period); follow-up from month 12 to month 24 | 39.1% sustained remission, 27% no sustained remission. Predictors for cross-sectional remission (calculated from month 12 data not from baseline): lower positive, negative, and general symptoms, less psychological side effects of medication, better social functioning |

| Gallego 201134 | Response = mild or better on all of the positive symptom items on the SADS-C + PD | 112 FE SCZ, schizophreniform or schizoaffective disorder SADS-C + PD; 16 weeks. | Cumulative response: 39.59% (week 8): 65.19% (week 16), rates increased 5% per 2 weeks. Relative reduction in symptom severity at week 4 (but not 2 or 8) was associated with responder status at week 16 |

| Johnson 201 251 | Cross-sectional remission | 95 FE SCHZ subjects followed at 6, 1 2, 60 months PANSS, GAF, BPRS | 68.4% cross-sectional remission. 14.7% returned to premorbid level of functioning. Predictors for remission: urbanicity, fluctuating course. Negative correlation of BPRS and insight scores at year 5, but in multivariate models the patients' understanding of illness had relatively low impact |

| Lambert 200852 | Recovery: Sustained symptomatic (CGI-SCH <3 ) + functional remission (occupation +independent + social). | 392 FE SCZ (European SOHO study subgroup) PANSS, CGI; 3 years. | 3-year rates for symptomatic/ functional remission: 60.3%/45.4%. 48.9% of subjects with combined sustained remission had adequate subjective wellbeing. 65.3% of subjects with symptomatic and functional remission at 3 months recovered, while only 10.0% of early non-remitted cases did. Predictors of recovery at end point: baseline functional status and early remission (during first 3 months) |

| Levine and Rabinowitz 201053 | Response trajectories | 49 FE with SCZ, schizophreniform, schizoaffective (recent onset, <60 month) PANSS, 6 months | 5-trajectory solution fitted data best (mixed mode latent regression). Poor response (14.5%): younger age of onset, lower BL scores on cognitive testing. Best response (17.1%): good premorbid function, higher BL scores on cognitive testing, no diagnosis of SCZ |

| Levine 2010.54 | Response trajectories | 263 subjects with SCZ, schizophreniform, schizoaffective disorder (recent onset, <60 month). PANSS, 2 years | 5-trajectory solution: The most improved trajectory group (22.9%), showed improvement until week 16 + subsequent stability. Characteristics of best response subgroup: no diagnosis of SCZ, good premorbid adjustment, lower BL PANSS |

| Malla 200655 | Remission (cross-sectional) | 107 FE SCZ patients; 2 years | 82.2% in remission. Positive predictors for remission: better pre-morbid adjustment, later age of onset, higher level of adherence to medication and shorter DUI |

| Nordon 201438 | Clinical response (CGI-S score <4 and ≥30% improvement) | 467 with anti psychotic-naive schizophrenia (mean baseline treated illness duration 2.7 years, moderately delusional thoughts = exclusion) CGI-S; 6 months | 53.3% responders; 5 trajectories: 43.6% “gradual response”, 28.5% “remaining mildly ill,” 13.3%: “unsustained improvement,” 9.6% “rapid response.” Predictor of good 6-month response: high baseline CGI, low level of negative symptoms Clinical improvement at 1 month predicted 6-month outcome |

| Pelayo-Teran 201456 | Response trajectories | 161 FE schizophreniform disorder, schizoaffective disorder, BRP. SAPS, SANS, 6 weeks | 5-trajectory solution for positive symptom response, 3 trajectories for disorganization, 5 trajectories for negative symptoms. Clear divergence of trajectories as early as week 2. Predictors of poor response of positive symptoms: Longer DUPs, cannabis. Predictors of poor response of negative symptoms: only cannabis |

| Petersen 200857 | Remission (cross-sectional) Recovery (symptomatic remission plus occupied) | 369 FE SCZ-spectrum disorder SANS, SAPS, GAF 2 years follow-through | Remission: 35.8%; Recovery 17.9%; 43.9% of recovered subjects on AP; Predictors of poor recovery: longer DUP, medication non-adherence, BL negative symptoms, substance-use disorder |

| Saravanan 201058 | Remission (symptom-free for 30 days); Relapse | 131 FE SCZ; BPRS, GAF 6 + 12 months follow-up | Remission at 1 year: 50.4%, 12% relapse. Predictors of remission: shorter DUP, change in insight and in BPRS (6-12 months) |

| Schennach-Wolf 201137 | Response = ≥ 50% PANSS reduction Remission (cross-sectional) | 224 FE SCZ, PANSS, 8 week data. Early response = ≥ 30% PANSS total score reduction by week 2 | 52% response. Predictors for response: early response, higher BL PANSS positive subscore. Predictors for remission: shorter DUP, lower PANSS general, early treatment response |

| Selten 200759 | Mid-term outcome | 125 FE schizophrenia-spectrum disorder; incidence study, 30 months follow-up | 56% poor outcome. Male sex in conjunction with substance abuse (cannabis) as predominant predictor of poor outcome. DUP failed to reach significance |

| Simonsen 201060 | Remission at 3 months and 2 years, with a definition of remission = 1 week without positive symptoms | 301 FE actively psychotic patients: SCZ, schizophreniform disorder, schizoaffective, BRP delusional disorder, affective psychosis with mood-incongruent psychotic features, psychotic disorder NOS; PANSS, GAF; 3 month, 2 year | 56.2% remission at 3 months, prolonged remission of positive symptoms: 68.7% DUP = only predictor for remission |

| Stauffer 201161 | Response (50% PANSS reduction) | 225 FE SCZ, schizophreniform or schizoaffective disorder PANSS, 12 weeks | 43.1% showed early response (defined as 26% reduction in PANSS) by week 2; and this was predictive for subsequent response No effect of age, gender, DUP |

| Stentebjerg-Olesen 201362 | Response = CGI-I of ≤ 3 | Adolescents, 58% male, SCZ, schizophreniform disorder, BRP, Psychosis NOS, CGI, 0-12 week | Week 4: 45.6% early response. Early response/early non-response predicted ultimate response/ultimate nonresponse (specificity of 85.3%). Predictors of early nonresponse: more EPS, higher age. Predictors of ultimate response: Early response, Psy NOS/brief psychotic disorder |

| Üçok 201163 | Sustained remission | 93 FE SCZ; Follow-up 1-12 Years (mean 4.8 years); Monthly BPRS, SANS, SAPS; focus first 24 months | 59.5% remission within 2 years, but 71.5% of these could not maintain sustained remission. 69% had at least one relapse during follow-up (up to 12 years). Remission predictors: Lower negative and higher positive symptoms at admission, lower positive symptoms at month 3 of follow-up, medication compliance in the first 6 months, and occupational status during the last month before admission |

| Ventura 201164 | Sustained remission (BPRS based analogous to Andreasen) Recovery (above + functional remission) | 77 FE SCZ, schizoaffective or schizophreniform disorder patients (83% male), on fluphenazine decanoate BPRS every 3 months; 12 months follow-through | 22% sustained remission at last follow-up, 36% remission for any 6-month period, 10% recovery. Hierarchical logistic regression failed to identify any significant predictor of symptom remission. No association between symptom remission and good functional outcome (which was associated with baseline WAIS) |

| Verma 201229 | Response (40% PANSS reduction; Sustained remission + Functional remission (GAF>60) = recovery | 1175 subjects with SCZ-spectrum disorder, BRP, affective psychosis, PANSS, GAF; 2 year | 3-month response: 45.6%; 2-year follow-up: 54.1% remission 29.4% symptomatic + functional remission at year 2. Predictors for remission and recovery: female, tertiary education, shorter DUP, early response at month 3, lower BL PANSS negative scores |

| Wunderink 200965 | Recovery (sustained symptomatic and functional remission) | 125 FE SCZ (with response to initial treatment; 48.6% of FE sample); PANSS; Followup: 9 months during the 2nd post-acute year | 52% symptomatic remission. 19.2% recovery; DUP and baseline social functioning independently predicted recovery. No recovery in subjects with DUP of ≥ 6 months |

| Zhang 201439 | Response ≥ 50% PANSS reduction Sustained remission | 398 FE; SCZ, acute schizophreniform disorder, never medicated, PANSS, 1 year | 70% responders at 1 year follow-up. Prediction of good response: shorter DUP, continuous treatment, higher BL general and subscale positive PANSS. 81.4% sustained remission: only DUP remained as independent factor (remitters: younger, less chronic prodromal phase, less family conflicts), relapse rate: 8.1% |

Significant patient, illness, treatment and environmental predictors are listed in Table III. Only those that emerged repeatedly are summarized below.

Table III. Selected significant predictors for poorer response or lower likelihood of remission in FE schizophrenia samples and in selected chronic schizophrenia studies published since 2006.

| Domain | Associated variable | Response | Remission | |

| Patient variable | ||||

| Age | None of the studies into response listed in table 2 found a significant effect of age29-69 | Older (Zhang 2014,39 Albert 201144) | ||

| Sex | Male: Rabinowitz 201475 | Male (Selten 2006,59 Derks 2010,48 Verma 2012,29 Diaz 2013,49 Albert 2011,44 Clemmensen 201268: early-onset schizophrenia) | ||

| No effect of sex in: Malla 2006,55 Emsley 2007,59 Lambert 2008, 52 Levine 2010,53 Saravanan 2010,58 Simonsen 2010,60 Agid 2011,43 Schennach 2011,37 Ventura 2011,64 Ucok 2011, Stentebjerg-Olesen 2013,62 Galderisi 2012,66 Wunderink 201367 | Female (clozapine: Nielsen 201269) | |||

| Premorbid adjustment | Poor (Malla 2006,55 Levine 2008,52 Levine 201053) | Poor (Addington and Addington 2008,40 (Crespo-Facorro 2007,47 Albert 201144) | ||

| Educational level | Lower education (Verma 2012,29 Diaz 201349) | |||

| Marital status | Single (Emsley 2006,41 Diaz 201349) Married (Teffarra 201270) | |||

| Neurological soft signs | Present (Emsley 200641) | |||

| Family history of psychosis | Positive family history (Crespo-Facorro 201336) | |||

| Illness variables | ||||

| Diagnosis | Diagnosis of schizophrenia (Crespo-Facorro 2007,47 Levine and Rabinowitz 2010,53 Levine 201054) | |||

| Age of Illness Onset | Younger age (Crespo-Facorro 2007,47 Semiz 2007,71 Levine and Rabinowitz 2010,53 Rabinowitz 201475) | Younger age (Tef 2012)70 | ||

| Duration of untreated psychosis | Longer DUP (Pelayo-Teran 2014, 56 Zhang 201439) | Longer DUP (Emsley 2006,41 2007,42 Addington and Addington 2008,40 Jeppesen 2008,72 Malla 2006,55 Simonsen 2010,60 Saravanan 2010,58 Schennach-Wolf 2011,37 Kurihara 2011,73 Thirthalli 2011,74 Verma 2012,29 Diaz 2013,49 Pelayo-Teran 2014,56Zhang 201439) | ||

| Illness duration | Longer (Malla 2006,55 Rabinowitz 201475) | Longer (Clemmensen 2012,69: early onset schizophrenia) | ||

| Baseline total symptom severity | Lower severity (Crespo-Facorro 2007,47 Boter 2009,35 Crespo-Facorro 2013,36 Zhang 2014, 35 Rabinowitz 201475) | Higher severity (Addington & Addington 2008,40; Schennach-Wolf 2011,37; Johnson 2012,51; Diaz 2013,49; Gäbel 201450) | ||

| Illness variables (cont'd) | Baseline positive symptoms | Lower severity (Schennach-Wolf 2011,37 Zhang 201439) | Higher severity (Addington and Addington 2008,40 Üçok 2011,63 Gäbel 201450) | |

| Baseline negative symptoms | Higher severity (Addington and Addington 2008,40; Üçok 2011,63 Verma 201229 Diaz 201349 Gäbel 201450) | |||

| Baseline general psychopathoIogy | Higher severity (Schennach-Wolf 2011,37 Gäbel 201450) | |||

| Baseline excited factor | Higher severity (Emsley 200641) | |||

| Baseline cognitive dysfunction | Greater dysfunction (Levine and Rabinowitz 201052) No effect of cognitive dysfunction (Chang 201145) | |||

| Insight | ||||

| Impaired insight (Johnson 201251) | Less improved insight (Saravanan 20105) | |||

| Functional status | General dysfunction (Nordon 201438) | Social dysfunction (Addington and Addington 2008,40 Gäbel 201450) Lack of professional occupation (Üçok 201163) | ||

| Comorbidities | Cannabis (Pelayo-Teran 201456: positive and negative symptom response) | Substance Misuse (Selten 2006, 59 Boter 200935) | ||

| Treatment variables | ||||

| Antipsychotic Adherence | Nonadherence (Malla 2006,55 Boter 2009,35 Zhang 201439) | Nonadherence (Üçok 201163); Functional remission: Dose reduction or discontinuation (Wunderink 201367) | ||

| Early treatment response/remission (at varying time points) | Early response (Levine 201054; SchennachWolf 2011,37 Stauffer 2011,61 Nordon 2014, 38 clozapine: Semiz 2007, 71 adolescents: Stentebjerg-Olesen 201358) | Early response/remission (Emsley 2006, 41 Derks 2010,48 Gallego 2011,34 SchennachWolf 2011, 37 Verma 201229) | ||

| Psychiatric hospitalization | Hospitalized (Crespo-Facorro 200740) | |||

| Side effects | Parkinsonism (Stentebjerg-Olesen 201363) Baseline akathisia (Derks 201048) | Patient-rated psychological side effects, eg, tension, depression, emotional indifference (Gäbel 201450) | ||

| Environmental variables | ||||

| Social support | More family conflict (Zhang 201439) | |||

| Rural environment | Rural environment (Johnson 201251) |

Patient variables

Reduced odds for response in FE schizophrenia samples were associated with poor premorbid adjustment and a positive family history for psychotic disorders (Table III).29 - 76

Reduced odds for remission were associated with male sex, poor premorbid adjustment, lower educational level, and single status (Table III).

Although considered a traditional indicator of poor outcome in schizophrenia, the role of male sex as a poor prognostic factor is currently controversial. Male sex was not a characteristic of poor treatment response in the majority of more recently published studies using criteria for response and remission in the very early post-acute period,37,42,43,52,54,55,58,63-65,67,77 except for a large meta-analysis of placebo-controlled studies in chronic schizophrenia.75 Conversely, studies which confirmed a poorer outcome in males referred mostly to time frames of at least 1 year.29,40,44,45,48,49,50,59,78 This poorer outcome in longer-term studies may relate to the increased risk for relapse in males6,17,18 or to risk factors for relapse, which are over-represented in males, including substance abuse,66,79,80 nonadherence,80,81 reduced help-seeking behavior,80 and increased baseline psychopathology.80

Poor premorbid adjustment is a traditionally implied predictor of poor outcome that has largely been confirmed by current studies.36,40,52,54,55,57,72,82 Poor premorbid functioning may be a nonspecific marker of greater neurodevelopmental disturbance, which negatively impacts the outcome. This notion is supported by a large international study,83 in which subjects with good premorbid functioning did not only achieve a more pronounced reduction in psychopathological measures, but required lower antipsychotic doses. Importantly, despite being slightly correlated, premorbid adjustment and DUP independently predict outcome.30,31,67,77

Illness variables

Reduced odds for response in FE psychosis were related to the diagnosis of schizophrenia, younger age of illness onset, longer DUP and illness duration, and to lower positive or general psychopathology, greater cognitive dysfunction, lower functional status, and substance use (Table III).

Reduced odds for remission were significantly associated with longer DUP and illness duration, higher severity of all aspects of psychopathology (total, positive, negative, general psychopathology, and excited factor symptoms), impaired insight and functional status, as well as substance-use disorder (Table III).

The seeming paradox that higher psychopathology predicts a higher chance of response but lower odds of remission has to do with the fact that response is a relative term, while remission depends on falling below an absolute threshold. The higher chance of response has to do with the so-called “law of initial value hypothesis” (see ref 76). This “law”84 states that “the higher the initial value, the greater the organism's response.” Treatment trajectories typically assume a hyperbolic decline function with major response gains over 2 to 4 weeks and relative leveling off thereafter, such that patients with higher initial psychopathology scores still remain above remission values while having reached the plateau period. In fact, more severe psychopathology at baseline reflects less amenable illness and consecutively low remission rates in FE12,29,40,41,49,50,54,57,63 and in chronic schizophrenia.85 By contrast, the lower the initial psychopathology score, the closer the patient is to reaching the the remission threshold.

Negative symptoms have been confirmed as major predictors of poor outcome.86-88 There is compelling evidence for a strong effect of negative symptoms on recovery and long-term functional outcomes7,88,89 but a predictive value of baseline negative symptoms for the relative treatment response, conceptualized as a short-term marker of efficacy, has not been demonstrated. Conversely, sustained remission, as an intermediate marker of treatment efficacy, has been associated with less negative symptom loads.29,40,42,60,73 Likely, this observation reflects the close association between negative symptoms and measures of real-life functioning, such as interpersonal behavior, community activities, and work skills,90,91 whereas proportional changes in PANSS, BPRS, or CGI may be dominated by positive symptoms during acute illness periods when treatment is often initiated. Thus, changes of sum scores fail to reflect the poor response of negative symptoms, as negative symptoms change relatively little with currently available treatments (see also trajectories for negative symptoms in refs 56, 76). However, this negative predictive value of greater negative symptom load may not apply to treatment with clozapine. Indeed, in a 4-month open study of treatment-resistant schizophrenia, higher baseline negative symptom severity was predictive for subsequent clozapine response.70

Earlier illness onset,71 especially during childhood and adolescence69 has traditionally been implied as a negative prognostic factor, which is confirmed by current studies. Interestingly, however, recent data suggested similar outcomes in early-onset schizophrenia and adult-onset schizophrenia when the DUP is short.92,93 There is emerging evidence that the effect of earlier illness onset may, at least in part, be mediated by longer illness duration and higher number of relapses that have been associated with a diminution of treatment response94,95 (see also below).

Response and remission rates were higher in studies including brief psychotic disorder and psychosis not otherwise specified (NOS),29,36,40,47,49,56,60,62,67 ie, when less severely ill and impaired subjects and those with shorter illness duration drive better long-term outcomes. By contrast, poorer outcomes are associated with the diagnosis of schizophrenia (ICD-10- or ZASM-IF-based, Tables II and III). To date, there are no published studies using DSM-5 criteria. However, despite a somewhat increased specificity of the criteria that now demand presence of two positive symptoms, applying DSM-5 is unlikely to significantly reduce the observed heterogeneity within patient groups diagnosed with schizophrenia.

Neurocognitive deficits have been well established in FE psychosis as independent disease characteristics in addition to positive and negative symptoms,96,97 but their effect on outcome parameters is less well understood. While several studies suggested an association of single neurocognitive measures and functional outcome parameters,98-103 a comprehensive synthesis of studies failed to demonstrate consistent or specific associations.104 It is likely that this failure relates to the diversity of studied neurocognitive measures, which were typically correlated as single factors with specific outcome parameters. By contrast, analysis of the neurocognitive data from the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) study demonstrated strong intercorrelations of neurocognitive domains.96 Moreover, neuropsychological testing requires a basic level of functioning and compliance, which is often not met at the initial stages of hospitalization/treatment initiation, such that baseline measurements are often obtained during stabilization, when (i) early treatment response has already occurred; and (ii) medications affected neurocognition.105

Comorbidities, especially substance abuse and dependence, interfere with treatment outcomes in schizophrenia, typically indicating a higher disease burden and greater nonadherence.106,107 Depressive symptoms, however, have been discussed more controversially. While the majority of studies have identified comorbid depression as a predictor of poor outcome,31,108 there have also been reports of higher baseline subsyndromal depressive symptoms as positive predictors of remission.109-111

Treatment variables

Reduced odds for response and remission were most robustly associated with antipsychotic treatment nonadherence and lack of early antipsychotic benefits and, to a lesser degree, to early side effects at therapeutic doses (Table III).

Antipsychotic adherence12,112 and maintenance antipsychotic treatment28,113 are among the most replicated indicators of better outcomes. Nevertheless, psychosocial treatments in combination with antipsychotics provide even better outcomes than antipsychotics alone.114,115

The value of presence/absence of minimal improvement in psychopathology at week 1 to 4 for later response status has been confirmed as a robust predictor of presence/absence of later response status. Evidence is somewhat more robust and conclusive for chronic patients,116-125 than for FE samples.34,37,41,48,61

Environmental variables

Lower odds for remission were associated with more family conflicts66 and rural environment51 in single studies respectively (Table III), but environmental factors are relatively under-represented in current predictor analyses.

Quality and quantity of social relationships have long been a topic of investigation, with high expressed emotions having been identified as a potentially modifiable poor prognostic factor in chronic patients.126 Interestingly, although with FE patients a similar degree of high expressed emotions in caregivers was reported, high expressed emotions seemed to be independent of patients' illness-related characteristics.127 Rather, high expressed emotions that lead to conflict, negative emotions, and social stress in chronic patients were related to caregiver coping style and signs of concern/involvement.

Discussion

This review supports the idea that a focus on clinical predictors of treatment outcomes is highly insufficient to parse patients into clinically meaningful subgroups of schizophrenia. Indeed, the wide variations of response and remission rates do not only reflect the different definitions, time frames and heterogeneity of study cohorts, often including subjects with psychosis NOS or brief psychotic disorder, but also reflect the true heterogeneity of schizophrenia. Biological markers, ideally those related to the underlying pathophysiology of different subtypes of the illness and with predictive value for specific treatments, are needed to substantially move the field forward.

Nevertheless, several clinical predictors exist that clinicians can act on now. These include longer DUP, nonadherence to antipsychotics, comorbidities (especially substance-use disorder), lack of early antipsychotic response, and lack of improvement with nonclozapine antipsychotics, predicting clozapine response,43 likely due to a pharmacologic probe enriching samples that do not respond to classic antidopaminergic activity.

The modifiable factor, longer DUP, is one of the most replicated predictors of poor short-term and long-term therapeutic outcome in schizophrenia.6, 128,129 DUP affects treatment response,39,36,78,130,132 remission,9,29,39,40-42,49,55,56,58,60,72 relapse liability,133-135 and, possibly, even long-term symptomatic outcomes.135-138 Although it has been suggested that remission becomes unlikely after a DUP of >6 months,65,135 substantial treatment effects can occur even with highly delayed treatment initiation.74,139 Possibly related to longer DUP are also self-stigma/perceived stigma, which have been associated with lower recovery rates in chronic patients, but also with higher nonadherence, which may be a mediating factor.140

The predictive value of the early neuroleptic response141 has been confirmed and further elaborated upon in current studies. Predictions have been extended to 1-year studies during which also the greatest degree of symptomatic improvement occurred in the first 2 to 4 weeks.142 The early response paradigm is predicated on the observation that using a <20% reduction in the PANSS or BPRS total score, which corresponds to less than minimally improved on the CGI-I,143 has good predictive validity for nonresponse using the same or more conservative definitions of ultimate nonresponse, such as <30%, <40%, or <50% reduction in the PANSS or BPRS total score. Interestingly, in contrast to chronic patients where results consistently showed that symptom improvements as early as week 1 or 2 predict ultimate response and remission,116-125 in FE samples it seems to take longer until one can declare a treatment failure,34,37,41,48,62

This discrepancy may be due to the fact that treatment response in FE psychosis is higher,12 but also slower or, at least, that there exist subgroups with a more delayed response,143-145 Differences may also relate to the fact that brains of patients with FE schizophrenia have not been exposed to longer-term dopamine blockade in the past, that the proportion of nonresponders is lower in FE patients, and that they typically respond to lower antipsychotic doses and are more sensitive to adverse effects, especially extrapyramidal and cardiometabolic side effects.146,147 Such adverse effect sensitivity may alter response trajectories due to higher early dropouts and/or nonadherence. Nevertheless, early treatment response at week 4 (which was the first post-baseline assessment time point) was also highly predictive for response/non-response in SGA-treated antipsychotic-naive adolescents with schizophrenia or psychosis NOS.63 Importantly, this study demonstrated that predictions need not be based on time-consuming scales, such as the PANSS or BPRS, but that less than minimally improved on the simple to use CGI-I scale was highly associated with not reaching much or very much improved scores at week 12.

Moreover, early nonresponse has also been associated with greater treatment discontinuation148,149 and non-adherence,149 which in turn is the most salient predictor of relapse.17 Further, if psychosis is indeed neurotoxic,16 it is crucial to limit the time of non-efficiently controlled psychosis as much as possible150 and alert clinicians to the low probability of treatment success even when extending the treatment duration, so that a switch should be considered. Nevertheless, to what degree a switch after early nonresponse to a first-line antipsychotic to another nonclozapine antipsychotic changes outcomes dramatically is still unclear.121

In this context, consideration needs to be given to recurrent illness episodes as a risk factor for poorer outcome. Although relatively few studies have addressed outcome dynamics over time, response rates seem to decline gradually during the early course of schizophrenia. For example, in subjects with up to 4 psychotic episodes, 17% failed to remit after each episode, irrespective of which episode it was.151 This finding implies that, even in previously treatment responsive subjects, each relapse bears the threat of developing treatment resistance. The different response rates across FE studies compared with multiepisode studies can be in part explained by the negative selection of multi-episode/ chronic schizophrenia in non-FE studies, where subjects with brief psychotic disorder are not included, nonadherent subjects, or subjects with multiple risk factors for relapses are overrepresented and the diagnostic certainty of schizophrenia vs other psychoses increases. However, the difference in response rates is also suggestive of within-subject changes in responsiveness to antipsychotics, which may reflect a neurobiological aspect of the underlying disease,16 In a naturalistic, algorithm-driven study of FE schizophrenia patients who received risperidone up to 12 weeks (4 weeks each of low, full, and then high-dose treatment) followed by olanzapine, or vice versa, treatment response rates dropped dramatically from the first trial (n=244, 74.5%) to the second trial (n=79, 16.6%).43 However, initiating clozapine increased response rates back to 75% (21/28), confirming that nonresponse to nonclozapine antipsychotics predicts response to clozapine, likely due to targeting nondopaminergic, possibly glutamatergic,152 transmission involved in the psychotic process. A CATIE data analysis has shown that patients responding well to olanzapine will likely not benefit from other non-olanzapine first-line antipsychotics.153 However, it is unclear if this may be due to greater treatment persistence that has been shown with olanzapine.154

A decline in response has been demonstrated for multiepisode patients. In one small cohort of FE schizophrenia (n=57), the average time to remission increased dramatically from the first episode (47 days) to the second (76 days) and third (130 days) episode respectively.155

In one small cohort of FE-schizophrenia (n=57), the average time to remission increased dramatically from the first episode (47 days) to the second (76 days) and third (130 days) episode respectively.155 Furthermore, analysis of the time courses of response in 97 subjects (including 16% with 2 relapses, and 35% with 3 or more relapses) from a multiphase, placebo-controlled relapse prevention trial indicated a slightly more rapid response in the post-relapse treatment phase until week 8, followed, however, by an earlier plateau of the response, with a small but significant difference in post-relapse PANSS scores.95 These data support the notion of within-subject changes in antipsychotic responsivity as contributors to the slow but progressive decline in treatment response in subgroups of patients with schizophrenia. However it is unclear, which factors determine response variability after relapse. Moreover, while many subjects return to their pre-relapse functioning level with reintroduction of treatment, no predictors of nonresponse after relapse have been identified.95

If ultimate nonremission is cause or consequence of nonresponse cannot be determined at this point, but there is clear evidence that early response and intermediate-term sustained remission are associated. For example, clinical improvement during the first month predicted 6-month remission56; lower relative reductions of psychopathology at week 6 predicted nonremission at 2 years41; lower positive symptom scores at 3 months predicted recovery at 2 to 3 years.52,64 A comparison of symptom domains used to define remission as predictors of functional 2-year outcome showed that the sequential number of months during which the severity criterion for remission of either positive symptoms, negative symptoms, or a combination of both was met, was significantly correlated with functioning at 2 years.156 Moreover, comparing symptom remission criteria with other factors influencing the course of illness, Boden and colleagues157 showed a strong association of early symptomatic remission and functioning at 5-year follow-up.

A step in the direction of understanding longitudinal trajectories of outcomes in schizophrenia is the construction of pathway models for the prediction of response likelihoods based on combined qualitative and quantitative disease markers. In a pooled dataset from 6 randomized, double-blind trials comparing olanzapine to other SGAs, moderately to severely ill patients (n = 1494) with chronic schizophrenia (mean illness duration = l0 years) underwent post-hoc classification and regression tree (CART) analyses to determine characteristics of treatment response defined as a >ou égale 30% reduction in total PANSS score,125 Technically, a classification analysis like CART analysis is based on binary recursive partitioning; meaning the analysis identifies nodes of decisions, at which point data are dichotomized and linked with a subsequent path leading to the next dichotomizing categorization. For each path, likelihoods can be estimated, resulting in a decision tree, in which the likelihood for each branch can be calculated. A ≥2 -point score decrease in ≥2 of 5 PANSS positive items (1 -delusions, 2-conceptual disorganization, 3-hallucinatory behavior, 6-suspiciousness, and 23-unusual thought content) at week 2 correctly categorized week 8 nonresponders with a predictive value of 0.75. 125 However, 24% of subjects were miscategorized, pointing to the necessity of an individualized approach.

Although response, remission, and recovery are closely related, the relationship to baseline symptoms or an absolute threshold, degree of improvement, temporal extension, and considered symptom/functional domain(s) vary. Response generally focuses on the amalgam of total symptom severity, comprised of positive, negative, and general symptomatology, at one or several sequential points in time. Remission, on the other hand, includes only positive and negative symptoms and requires 6 months of no more than minimal symptomatology. Recovery requires social and educational/vocational functioning in addition to remission and both need to be sustained for 1 to 2 years, depending on the definition.19 Like the diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia, however, none of these concepts considers cognitive dysfunction, although cognition is clearly relevant for functioning.158 Nevertheless, due to the differences, predictors of response, remission, and recovery may overlap to a certain degree, but are also bound to differ.

Continued antipsychotic treatment has been examined for potentially detrimental long-term effects,89,159 but nonadherence has emerged as a reliable and addressable risk factor for lack of response and remission.160 Moreover, volumetric measures have shown that the time in relapse was far more strongly related to total brain and frontal lobe volume reductions than time on antipsychotic treatment.161 Relapses in FE patients were most highly predicted by stopping antipsychotic treatment8,12,112 and relapse rates approached 90% to 100% in FE patients who had been stabilized and in whom antipsychotics were stopped by design,8 even if tapered slowly over 6 months.162

Conclusions

Differences in concepts, definitions, methodology, and stages of the illness complicate the identification of both clinical and biological markers of response, remission, and recovery. Ultimately, only a better pathophysiological understanding of the different disease processes leading to the expression of schizophrenia and its exacerbation and improvement will help identify robust and generalizable predictors of therapeutic response, Until such data become available, clinicians are left with relatively little that can help stratify, let alone personalize, treatment based on predicting outcomes. The modifiable risk factors for poor therapeutic outcomes that clinicians can act upon right now include longer DUP, nonadherence to antipsychotics, comorbidities (substance misuse and depression), lack of early antipsychotic response, and lack of improvement with nonclozapine antipsychotics, predicting clozapine response. It is hoped that this limited situation will improve as the pathophysiological understanding of schizophrenia increases and/or new treatments for specific aspects of schizophrenia become available, which go beyond the treatment of positive symptoms and agitation and which have mechanisms of action that go beyond modulating dopamine and serotonin transmission.

Financial disclosure: (Dr Carbon has the same disclosure information as Dr Correll due to family relationship). Dr Correll has been a consultant and/ or advisor to or has received honoraria from: Actelion, Alexza; American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cephalon, Eli Lilly, Genentech, Gerson Lehrman Group, Intracellular Therapies, Lundbeck, Medavante, Medscape, Merck, National Institute of Mental Health, Janssen/J&J, Otsuka, Pfizer, Prophase, Roche, Sunovion, Takeda, Teva, and Vanda. He has received grant support from BMS, Feinstein Institute for Medical Research, Janssen/J&J, National Institute of Mental Health, Novo Nordisk A/S and Otsuka.

Contributor Information

Maren Carbon, The Zucker Hillside Hospital, Psychiatry Research, North Shore - Long Island Jewish Health System, Glen Oaks, New York, USA.

Christoph U. Correll, The Zucker Hillside Hospital, Psychiatry Research, North Shore - Long Island Jewish Health System, Glen Oaks, New York, USA; Hofstra North Shore LIJ School of Medicine, Hempstead, New York, USA; The Feinstein Institute for Medical Research, Manhasset, New York, USA; Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, New York, USA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Huber G., Gross G., Schüttler R., Linz M. Longitudinal studies of schizophrenic patients. Schizophr Bull. 1980;6:592–605. doi: 10.1093/schbul/6.4.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ciompi L. Catamnestic long-term study on the course of life and aging of schizophrenics. Schizophr Bull. 1980;6:606–618. doi: 10.1093/schbul/6.4.606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Breier A., Schreiber JL., Dyer J., Pickar D. National Institute of Mental Health longitudinal study of chronic schizophrenia. Prognosis and predictors of outcome. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48:239–246. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810270051007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ram R., Bromet EJ., Eaton WW., Pato C., Schwartz JE. The natural course of schizophrenia: a review of first-admission studies. Schizophr Bull. 1992;8:185–207. doi: 10.1093/schbul/18.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hegarty JD., Baldessarini RJ., Tohen M., Waternaux C., Oepen G. One hundred years of schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of the outcome literature. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:1409–1416. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.10.1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Altamura AC., Bobo WV., Meltzer HY. Factors affecting outcome in schizophrenia and their relevance for psychopharmacological treatment. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;22:249–267. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0b013e3280de2c7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Möller HJ., Jäger M., Riedel M., Obermeier M., Strauss A., Bottlender R. The Munich 15-year follow-up study (MUFUSSAD) on first-hospitalized patients with schizophrenic or affective disorders: comparison of psychopathological and psychosocial course and outcome and prediction of chronicity. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2010;260:367–384. doi: 10.1007/s00406-010-0117-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zipursky RB., Menezes NM., Streiner DL. Risk of symptom recurrence with medication discontinuation in first-episode psychosis: a systematic review. Schizophr Res. 2014;152:408–414. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schennach R., Riedel M., Musil R., Moller HJ. Treatment response in firstepisode schizophrenia. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2012;10:78–87. doi: 10.9758/cpn.2012.10.2.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lang FU., Kösters M., Lang S., Becker T., Jäger M. Psychopathological long-term outcome of schizophrenia - a review. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2013;127:173–182. doi: 10.1111/acps.12030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zipursky RB., Reilly TJ., Murray RM. The myth of schizophrenia as a progressive brain disease. Schizophr Bull. 2013;39:1363–1372. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robinson DG., Woerner MG., Alvir JM., et al Predictors of treatment response from a first episode of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:544–549. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.4.544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cosgrove VE., Suppes T. Informing DSM-5: biological boundaries between bipolar I disorder, schizoaffective disorder, and schizophrenia. BMC Med. 2013;11:127. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jablensky A. Subtyping schizophrenia: implications for genetic research. Mol Psychiatry. 2006;11:815–836. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kane JM., Correll CU. Past and present progress in the pharmacologic treatment of schizophrenia. J. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:1115–1124. doi: 10.4088/JCP.10r06264yel. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Remington G., Foussias G., Agid O., Fervaha G., Takeuchi H., Hahn M. The neurobiology of relapse in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2014;152:381–390. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2013.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Olivares JM., Sermon J., Hemels M., Schreiner A. Definitions and drivers of relapse in patients with schizophrenia: a systematic literature review. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2013;12:32. doi: 10.1186/1744-859X-12-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gaebel W., Riesbeck M. Are there clinically useful predictors and early warning signs for pending relapse? Schizophr Res. 2014;152:469–477. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liberman RP., Kopelowicz A. Recovery from schizophrenia: a concept in search of research. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56:735–742. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.6.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jääskeläinen E., Juola P., Hirvonen N., et al A systematic review and metaanalysis of recovery in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2013;39:1296–12306. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lehman AF., Lieberman JA., Dixon LB., et al American Psychiatric Association; Steering Committee on Practice Guidelines. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia, second edition. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(2 suppl):1–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Correll CU., Kishimoto T., Nielsen J., Kane J. Clinical relevance of treatments for schizophrenia. Clin Ther. 2011;33:616–39. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2011.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCabe R., Saidi M., Priebe S. Patient-reported outcomes in schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;50(suppl):s21–28. doi: 10.1192/bjp.191.50.s21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robinson D., Woerner MG., Alvir JM., et al Predictors of relapse following response from a first episode of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:241–247. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.3.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meltzer HY. Treatment-resistant schizophrenia-the role of clozapine. Curr Med Res Opin. 1997;14:1–20. doi: 10.1185/03007999709113338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leucht S., Arbter D., Engel RR., Kissling W., Davis JM. How effective are second-generation antipsychotic drugs? A meta-analysis of placebo-controlled trials. Mol Psychiatry. 2009;14:429–447. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lambert M., Karow A., Leucht S., Schimmelmann BG., Naber D. Remission in schizophrenia: validity, frequency, predictors, and patients' perspective 5 years later. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2010;12:393–407. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2010.12.3/mlambert. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leucht S., Tardy M., Komossa K., et al Antipsychotic drugs versus placebo for relapse prevention in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2012;379:2063–2071. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60239-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Verma S., Subramaniam M., Abdin E., Poon LY., Chong SA. Symptomatic and functional remission in patients with first-episode psychosis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2012;126:282–289. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2012.01883.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perkins D., Lieberman J., Gu H., et al HGDH Research Group. Predictors of antipsychotic treatment response in patients with first-episode schizophrenia, schizoaffective and schizophreniform disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;185:18–24. doi: 10.1192/bjp.185.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Perkins DO., Gu H., Weiden PJ., McEvoy PJ., Hamer RM., Lieberman JA. Comparison of Atypicals in First Episode study group. Predictors of treatment discontinuation and medication nonadherence in patients recovering from a first episode of schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, or schizoaffective disorder: a randomized, double-blind, flexible-dose, multicenter study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:106–113. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Levine SZ., Rabinowitz J., Engel R., Etschel E., Leucht S. Extrapolation between measures of symptom severity and change: an examination of the PANSS and CGI. Schizophr Res. 2008;98:318–322. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Andreasen NC., Carpenter WT., Jr , Kane JM., Lasser RA., Marder SR., Weinberger DR. Remission in schizophrenia: Proposed criteria and rationale for consensus. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:441–449. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.3.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gallego JA., Robinson DG., Sevy SM., et al Time to treatment response in first-episode schizophrenia: should acute treatment trials last several months? J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72:1691–1696. doi: 10.4088/JCP.10m06349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boter H., Peuskens J., Libiger J. EUFESTstudy group. Effectiveness of antipsychotics in first-episode schizophrenia and schizophreniform disorder on response and remission: an open randomized clinical trial (EUFEST). Schizophr Res. 2009;115:97–103. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Crespo-Facorro B., de la Foz VO., Ayesa-Arriola R., et al Prediction of acute clinical response following a first episode of non affective psychosis: results of a cohort of 375 patients from the Spanish PAFIP study. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2013;44:162–167. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2013.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schennach-Wolff R., Jager M., Mayr A., et al Predictors of response and remission in the acute treatment of first-episode schizophrenia patients-is it all about early response? Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011;21:370–378. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nordon C., Rouillon F., Azorin JM., Barry C., Urbach M., Falissard B. Trajectories of antipsychotic response in drug-naive schizophrenia patients: results from the 6-month ESPASS follow-up study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2014;129:116–125. doi: 10.1111/acps.12135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang HX., Shen XL., Zhou H., Yang XM., Wang HF., Jiang KD. Predictors of response to second generation antipsychotics in drug naive patients with schizophrenia: a 1 year follow-up study in Shanghai. Psychiatry Res. 2014;215:20–25. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2013.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Addington J., Addington D. Symptom remission in first episode patients. Schizophr Res. 2008;106:281–285. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Emsley R., Oosthuizen PP., Kidd M., Koen L., Niehaus DJ., Turner HJ. Remission in first-episode psychosis: predictor variables and symptom improvement patterns. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:1707–1712. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Emsley R., Rabinowitz J., Medori R. Early Psychosis Global Working Group. Remission in early psychosis: rates, predictors, and clinical and functional outcome correlates. Schizophr Res. 2007;89:129–139. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Agid O., Arenovich T., Sajeev G., et al An algorithm-based approach to first-episode schizophrenia: response rates over 3 prospective antipsychotic trials with a retrospective data analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72:1439–1444. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05785yel. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Albert N., Bertelsen M., Thorup A., et al Predictors of recovery from psychosis Analyses of clinical and social factors associated with recovery among patients with first-episode psychosis after 5 years. Schizophr Res. 2011;125:257–266. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chang WC., Hui CL., Tang JY., Wong GH., Lam MM., Chan SK., Chen EY. Persistent negative symptoms in first-episode schizophrenia: a prospective three-year follow-up study. Schizophr Res. 2011;133:22–28. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chang WC., Tang JY., Hui CL., et al Duration of untreated psychosis: relationship with baseline characteristics and three-year outcome in firstepisode psychosis. Psychiatry Res. 2012;198:360–365. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2011.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Crespo-Facorro B., Pelayo-Teran JM., Perez-lglesias R., et al Predictors of acute treatment response in patients with a first episode of non-affective psychosis: sociodemographics, premorbid and clinical variables. J Psychiatr Res. 2007;41:659–666. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Derks EM., Fleischhacker WW., Boter H., Peuskens J., Kahn RS. EUFEST Study Group. Antipsychotic drug treatment in first-episode psychosis: should patients be switched to a different antipsychotic drug after 2, 4, or 6 weeks of nonresponse? J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010;30:176–180. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e3181d2193c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Diaz I., Pelayo-Teran JM., Perez-lglesias R., et al Predictors of clinical remission following a first episode of non-affective psychosis: sociodemographics, premorbid and clinical variables. Psychiatry Res. 2013;206:181–187. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gaebel W., Riesbeck M., Wolwer W., et al Rates and predictors of remission in first-episode schizophrenia within 1 year of antipsychotic maintenance treatment. Results of a randomized controlled trial within the German Research Network on Schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2014;152:478–486. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2013.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Johnson S., Sathyaseelan M., Charles H., Jeyaseelan V., Jacob KS. Insight, psychopathology, explanatory models and outcome of schizophrenia in India: a prospective 5-year cohort study. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:159. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-12-159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lambert M., Naber D., Schacht A., Wagner T., Hundemer HP., Karow A., Huber CG., Suarez D., Haro JM., Novick D., Dittmann RW., Schimmelmann BG. Rates and predictors of remission and recovery during 3 years in 392 never-treated patients with schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2008;118:220–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Levine SZ., Rabinowitz J. Trajectories and antecedents of treatment response over time in early-episode psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36:624–632. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Levine SZ., Rabinowitz J., Case M., Ascher-Svanum H. Treatment response trajectories and their antecedents in recent-onset psychosis: a 2-year prospective study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 20;30:446–449. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e3181e68e80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Malla A., Norman R., Schmitz N., et al Predictors of rate and time to remission in first-episode psychosis: a two-year outcome study. Psychol Med. 2006;36:649–658. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706007379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pelayo-Teran JM., Diaz FJ., Perez-lglesias R., et al Trajectories of symptom dimensions in short-term response to antipsychotic treatment in patients with a first episode of non-affective psychosis. Psychol Med. 2014;44:37–50. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713000330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Petersen L., Thorup A., 0qhlenschlaeger J., et al Predictors of remission and recovery in a first-episode schizophrenia spectrum disorder sample: 2-year follow-up of the OPUS trial. Can J Psychiatry. 2008;53:660–670. doi: 10.1177/070674370805301005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Saravanan B., Jacob KS., Johnson S., Prince M., Bhugra D., David AS. Outcome of first-episode schizophrenia in India: longitudinal study of effect of insight and psychopathology. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;196:454–459. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.068577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Selten JP., Veen ND., Hoek HW., et al Early course of schizophrenia in a representative Dutch incidence cohort. Schizophr Res. 2007;97:79–87. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Simonsen E., Friis S., Opjordsmoen S., et al Early identification of nonremission in first-episode psychosis in a two-year outcome study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2010;122:375–383. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2010.01598.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stauffer VL., Case M., Kinon BJ., et al Early response to antipsychotic therapy as a clinical marker of subsequent response in the treatment of patients with first-episode psychosis. Psychiatry Res. 2011;187:42–48. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stentebjerg-Olesen M., Jeppesen P., Pagsberg AK., et al Early nonresponse determined by the clinical global impressions scale predicts poorer outcomes in youth with schizophrenia spectrum disorders naturalistically treated with second-generation antipsychotics. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2013;23:665–675. doi: 10.1089/cap.2013.0007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ucok A., Serbest S., Kandemir PE. Remission after first-episode schizophrenia: results of a long-term follow-up. Psychiatry Res. 2011;189:33–37. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ventura J., Subotnik KL., Guzik LH., et al Remission and recovery during the first outpatient year of the early course of schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2011;132:18–23. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.06.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wunderink L., Sytema S., Nienhuis FJ., Wiersma D. Clinical recovery in first-episode psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35:362–369. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Galderisi S., Bucci P., Ucok A., Peuskens J. No gender differences in social outcome in patients suffering from schizophrenia. Eur Psychiatry. 2012;27:406–408. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2011.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]