Abstract

Morality is at the core of what it means to be social. Moral judgments require the recognition of intentionality, that is, an attribution of the target’s intentions towards another. Most research on the origins of morality has focused on intragroup morality, which involves applying morality to individuals in one’s own group. Yet, increasingly, there has been new evidence that beginning early in development, children are able to apply moral concepts to members of an outgroup as well, and that this ability appears to be complex. The challenges associated with applying moral judgments to members of outgroups includes understanding group dynamics, the intentions of others who are different from the self, and having the capacity to challenge stereotypic expectations of others who are different from the ingroup. Research with children provides a window into the complexities of moral judgment and raises new questions, which are ripe for investigations into the evolutionary basis of morality.

Keywords: moral judgment, developmental psychology, intergroup relations, social exclusion

The origins of morality

Developmental psychologists have demonstrated ways in which children resolve conflicts in non-aggressive ways. Through negotiation, bargaining, and compromising about the exchange of resources, for example, children learn about reciprocity, mutuality, equality and fairness (Killen & Rutland, 2011). Parallel findings have been revealed with non-human primates in which animals resolve conflicts in ways other than through aggressive means (Cords & Killen, 1998; de Waal, 2006; Verbeek, Hartup, & Collins, 2000). These findings point to a social origin of nature, rejecting a solely aggressive view of human or non-human primate nature. In developmental psychology, theories of the origins of sociality stem from biological and evolutionary theories (de Waal, 1996, 2006), as well as from philosophical theories for defining morality (Gewirth, 1978; Rawls, 1971; Sen, 2009). Fundamentally, a developmental approach is one that examines the ontogenetic course of sociality, studying the change over time, origins, emergence, and source of influence.

In this article, we review the developmental evidence for the emergence of sociality, the origins of moral judgments, and the developmental trajectories regarding moral judgment through childhood. We identify the social interactional basis for moral judgments and the challenges that come with applying moral judgments to everyday interactions. A basic question often posed is whether sociality is learned or innate. Our argument is that it is both. Sociality (and morality) is constructed through a process of interactions, reflections, and evaluations. Peer interactions play a unique role enabling children to engage with equal partners that create conflict which force individuals to reflect, abstract, and form evaluations of their everyday interactions. The argument that sociality precedes morality has also received support from biological and evolutionary accounts of morality (see de Waal, this issue). This view stems from Piaget’s (1932) foundational work on moral judgment in which he observed children playing games and interviewed them about their interpretations of the fairness of the rules that governed their interactions (Carpendale & Lewis, 2006). Piaget’s theory was quite different from Freud’s (1930/1961) and Skinner’s (1974) who postulated that morality was acquired through external socialization, by parents or external contingencies in the environment. Thus, the proposal by Piaget is bottom - up, not top-down. Through a reciprocal process of judgment – action-reflection, children construct knowledge and develop concepts that enable them to function in the world. Adaptation is a key mechanism by which children develop, change, and acquire knowledge. This view of morality is consistent with evolutionary, biological, and comparative perspectives as well (Churchland, 2011; de Waal, 2006). As stated by Darwin (1871/2004), morality is a result of both social predispositions as well as intellectual faculties, defined as reciprocity, or the Golden Rule.

Thus, moral judgments do not emerge in a vacuum. Morality originates through the daily interactions the child experiences with peers, adults, family members, and friends. What happens very early in development is the emergence of group identity, and group affiliation. Through interacting with members of one’s own group and other groups, children have the social-cognitive task of balancing individual needs, group needs, and the motivation to be fair and just. What makes it complex is that these challenges involve attributions of intentions of others, both members of the “ingroup” as well as the “outgroup” (as explained below). Intentionality has been studied by moral theorists as well as researchers who examine children’s understanding of mental states, often referred to as theory of mind.

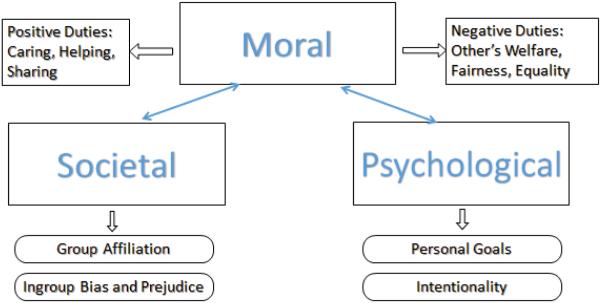

The set of challenges created by acquiring moral norms in group interactions, along with a developing sense of intentionality understanding has been studied by both social and developmental psychologists for over a decade (see Mulvey, Hitti, & Killen, 2013), and this research will constitute a central focus of the article. To do this we draw on several theories: 1) social domain theory (Smetana, 2006; Turiel, 1983) which has identified three domains of knowledge: the moral, societal, and psychological (see Figure 1); 2) developmental theories of group identity (Abrams & Rutland, 2008; Nesdale, 2004), which have characterized how group identity emerges in development; and 3) theory of mind (Wimmer & Perner, 1983), which has revealed how children form an understanding of mental states and intentionality. Beginning with social domain theory as the core approach, we have depicted how other dimensions of social life bear on the acquisition of morality (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Depiction of three domains of social life, the moral, societal, and psychological, and key constructs investigated in developmental research on morality.

Research on moral knowledge has shown that children distinguish moral knowledge from other non-moral social rules early in development, and that their social interactional experiences lead to these judgments. The moral domain refers to inter-individual treatment of others with respect to fairness, others’ welfare, equal treatment, and justice. In this article, we differentiate morality that pertains to positive duties (helping, caring, sharing) from morality that pertains to negative duties (avoid harm to others, unfair distribution of resources, inequality), which will be discussed in more detail below. The societal domain refers to behavioral uniformities that promote the smooth functioning of social groups, such as customs, conventions, rules, and rituals established by groups. The psychological domain refers to areas of individual prerogatives and personal choice, such as choice of friendships or personal goals. Over 30 years of research has empirically demonstrated that very young children, prior to direct teaching, make distinctions between rules that concern fairness, and those that concern conventions, (for example, Smetana, 2011; Turiel, 1998), and that children recognize the psychological domain as an area that is distinct from rules about morality and conventions.

Yet, most conflicts in social life are multifaceted, reflecting multiple domains of knowledge. We are specifically interested in conflicts that reflect the demands to be fair (morality) and to be loyal to the group (group identity) as well as between concerns for fairness, and a lack of the recognition of other’s intentions, motivations, and desires (theory of mind). These conflicts reflect everyday interactions between individuals, and in this paper we will highlight these types of experiences which, when resolved, have the potential to contribute to sophisticated moral perspectives.

In this review, we make two distinctions about morality, drawn from moral philosophy (Kant, 1785/1959): the identification of positive and negative duties. Positive duties are duties to be benevolent, prosocial, and generous towards others. These are the values of being positive which do not meet a high expectation for obligatoriness because of the impossibility of “doing good” every moment (see Williams, 1981). Negative duties are obligations that one must uphold, such as not harming others, not denying resources, nor refusing basic rights. These obligations are absolute values in that to commit harm, deny resources, and refuse basic rights constitute moral transgressions (in the way that not helping or giving to charity does not constitute a moral transgression). As we will discuss in this article, however, the term “absolute” takes a different meaning in the context of developmental science research from how it has been formulated in moral philosophy. Developmental science research has revealed the importance of context for determining what creates harm to another, for example, who “counts” as the “other,” and many other factors, and to this extent the absolute quality of moral norms is not a rigid application of the maxim to all social encounters. The absolute quality of moral norms has to do with the requirement that moral norms are not arbitrary, alterable, changeable, or a matter of group consensus and authority mandates, in contrast to non-moral transgressions (such as conventions or etiquette), as we discuss below.

As we will review below, much of the very early research on the roots of morality pertains to positive duties. This focus, by definition, provides the building blocks for morality. These data have not yet provided a basis for demonstrating the obligatoriness of morality, which is revealed more clearly when an act constitutes a moral transgression, as distinct from a positive act towards others. As we will review, by childhood, it becomes clear how morality constitutes an understanding of the negative duties. We will review evidence for the emergence of a prosocial disposition in early childhood, and then review research demonstrating moral judgments, and moral orientations in childhood through adolescence. We will conclude with a reflection about cross-species comparisons and humanity in the area of morality.

Origins of Sociality

By the time infants reach their first birthday, they are already equipped with some of the rudimentary precursors to social and moral behavior. At a most basic level, they understand who people are, and differentiate between humans and other animate and inanimate objects (Thompson, 2006). Additionally, young infants possess at least some understanding of another’s goals and intentions (Woodward, 2008, 2009). From these findings, it is clear that by the first birthday, if not sooner, children are already beginning to understand who people are and, more importantly, what makes them special- their actions, desires, and intentions. Infants are not, however, limited to simply understanding who –and what- humans are, they are also predisposed to orient towards, and interact with, other humans. This early social orientation is the core root of social and moral cognition, as it binds the infant into the social world as an active social agent.

With these early capacities, infants also actively interact with others in social ways to form attachments and relationships. Social exchanges and reciprocity with parents (e.g., attention sharing and imitation) are the building blocks of social cognition, and help foster healthy attachments and relationships with others (Cassidy, 2008). These early attachments are then the first steps in the development of a behavioral system that encourages close proximity and –importantly- frequent interactions with parents, and eventually peers. Through these relationships, infants develop the motivation to be socially involved and develop a more sophisticated understanding of others knowledge, emotions, and desires as well as their own self-awareness and awareness of social-conventions and morality (Killen & Rutland, 2011).

Given that from a very young age humans form deep, meaningful attachments and relationships with those around them, and that infants actively interpret experiences with those early relationships, it should not be surprising that infants begin to prefer interactions that are positive and cooperative over those that are negative and preventative. In a recent line of studies building from previous research on helper/hinderer distinctions (Kuhlmeier, Bloom, & Wynn, 2003), Hamlin, Wynn, and Bloom (2007) tested whether infants differentiate between characters who had acted prosocially or antisocially toward another character. Infants as young as 6-months-old were shown a short play with geometric shapes as agents. In the play, an agent unsuccessfully attempted to climb a hill, and was then either helped (pushed up the hill) or hindered (pushed down the hill) by another agent. Infants showed a looking time and reaching preference for the helping agent over the hindering agent. Furthermore, they found that infants did not only prefer the helper to the hinderer, but also preferred the helper over a neutral agent (showing a “liking” for the helper) and preferred a neutral agent over the hinderer (showing an avoidance of the hinderer). This suggests that infants are, indeed, making social judgments based on their observations of others’ actions- preferring those who act prosocially and avoiding those who harm others.

While these early social judgments may represent the building blocks to moral judgments, it is not clear to what extent these social judgments are moral judgments themselves. These social judgments may be closer to an “I don’t like those who harm others, and I like it when those I don’t like are harmed” type of judgment than an ‘ought’ to type of moral judgment; “One ought not to harm others, and those who harm others ought to be punished”. The former type of evaluation is subject to the personal likes and dislikes of the individual infant and may be more in line with personal judgments like, “I like jazz musicians and dislike rock-and-roll musicians, and I like it when jazz musicians succeed and rock-and-roll musicians fail”, whereas the latter focuses on the intrinsic moral rights that extend to all humans.

This line of research has provided valuable insight into infants’ social understanding. Infants are able to make social judgments of puppets and geometric shapes in a variety of scenarios, and incorporate the mental states of the agents’ into their judgments. Furthermore, infants appear to be making, “enemy of my enemy” judgments, as they prefer those who punish antisocial agents to those who reward them. From this, it seems clear that infants are not only bound into their social world through their social relationships and attachments, but are evaluating others based on their actions and forming judgments about what they would like to happen to those others.

Beneficence

Given that infants as young as 6-months-old prefer agents who help others, an important question is whether infants themselves are willing to help or not, and what guidelines they use to determine who and when to help. Recent developmental research has found that, across a wide range of studies, toddlers and children show the capacity, and tendency, to instrumentally help others achieve their goals. Studies have found that if an experimenter drops an object onto the floor and unsuccessfully tries to reach for it, toddlers 14-months-old and older will instrumentally help the experimenter by walking over to pick up the dropped object and handing it to the experimenter (Over & Carpenter, 2009; Warneken & Tomasello, 2006). Additionally, these prosocial helping behaviors do not appear to be motivated by the expectation of a material reward (Warneken et al., 2007), which has actually been found to decrease helping behaviors after toddlers stopped receiving the reward (Warneken & Tomasello, 2008).

A recent study conducted by Dahl, Shuck, and Campos (2013) examined if 17-, 22-, and 26-month-old toddlers were willing to help an antisocial agent. They found that it was not until 26-months-old that toddlers began to consistently help a prosocial agent over an antisocial agent, and that even 26-month-old toddlers helped an antisocial agent if given the opportunity to. It is important to note, however, that in this study, contrary to the findings of Hamlin and colleagues with geometric shapes and puppets, it was not until 26-months-old that toddlers distinguished between the prosocial and antisocial, human agents while they were acting prosocially or antisocially.

Brownell and colleagues have also examined infants’ ability to coordinate their actions in order to cooperate with peers (Brownell & Carriger, 1991; Brownell, Ramani, & Zerwas, 2006) which differs from research on cooperation between an infant (14 months) and an informed adult experimenter (see Warneken & Tomasello, 2007). In non-verbal tasks -designed to enable children to coordinate their behavior with one another- by Brownell and colleagues, 12- and 18-month-olds were unable to intentionally coordinate their behaviors to achieve a common goal. On the few instances in which 18-month-olds did coordinate their behaviors, it was coincidental and unstructured. No 12-month-old dyad ever cooperated. However, by 24-months-old, toddlers were able to achieve their collective goal through cooperatively coordinating their behaviors and by 30-months-old even gesturally and verbally communicated directions to one another. Brownell and colleagues argued that this developmental shift is linked to infants’ and toddlers’ developing ability to interpret the desires, intentions, and goals of their peers, whose desires, intentions, and goals are especially capricious and difficult to interpret.

The collective findings of the studies presented suggest that infants are deeply involved in their social world through their relationships and attachments, make social judgments about others, and, by toddlerhood, are highly motivated to help others when they need assistance to achieve their goal. Infants begin to establish attachments in the first few months of life. Around 6-months-old, infants begin to make rudimentary social judgments about non-human agents. As toddlers become better apt to move around in their social world, toddlers as young as 14-months-old begin to instrumentally help adults with their physical goals, and begin coordinating their behavior with peers by 24-months-old. Then, around 26-months old, toddlers begin to preferentially help certain people over others.

Social interactions and judgments regarding moral and conventional transgressions

During the preschool period moral judgments are spontaneously articulated by children towards others during their encounters (and conflicts). To examine young children’s actual responses to one another in social interactions regarding morally relevant issues, Nucci and Turiel (1978) observed children’s social interactions during free-play in preschools. Nucci and Turiel examined the nature of preschool children’s and teacher’s responses to both conventional and moral transgressions committed by preschool children. They found that both children and adults responded to moral transgressions by focusing primarily on the intrinsic consequences of the actions. Children, often the victim of the transgressions, responded with direct feedback regarding the harm or loss they experienced due to the transgression.

Complementing these responses, teachers responded by focusing on the effects of the transgression on the victim when discussing the transgression with the transgressor. However, in contrast to the responses to moral transgressions, only teachers –not children- responded consistently to conventional transgressions (children often ignored the transgressions). Teachers were found to respond to conventional transgressions by mentioning school rules, invoking sanctions or punishments, discussing the disruptive consequences of the transgressions, and by using commands to stop the transgression (e.g., “sit down”). These findings demonstrate that children hear different messages about, and respond differently to, social interactions in the contexts of moral and social conventional events.

To extend these findings, Nucci and Nucci (1982) examined school-aged children’s developing conceptions of moral and conventional transgressions through both observational and interview methodologies. They found that both children’s and teachers’ responses differed between conventional events and moral events. Consistent with Nucci and Turiel (1978), they found that children were much less likely to respond to conventional transgressions than moral transgressions, and their responses to moral transgressions revolved around the intrinsic harm or injustice to the victim that was caused by the act. Children of all ages also responded to moral transgressions with more appeals for teacher intervention as well as direct retaliatory acts directed at the transgressor, although the latter response increased with age. Children were found to respond to conventional transgressions increasingly with age, and mention concerns for the social order, such as classroom rules and social norms. Furthermore, during interviews with children about ongoing events, children were found to make the conceptual distinction between the observed moral and conventional transgressions. Participants judged moral transgressions to be wrong regardless of the presence or absence of a rule or social norm, but judged conventional transgressions as wrong only if the rule or social norm existed in their school or classroom. These findings indicate that children differentiate between naturally occurring moral and conventional transgressions in terms of their observed reactions as well as in the interview context. A striking finding regarding these data pertains to the correspondence between behavior and judgment, which is a central issue in moral development. Children’s behavior regarding moral transgression reflected their judgments in interviews about hypothetical vignettes that closely matched children’s everyday interactions.

Similar to the findings in preschool children, school-aged children were more likely to respond to moral than conventional transgressions, and responded with statements about the harm done to, or loss experienced by, the victim in moral contexts and responded with statements about school or classroom rules and norms in conventional contexts. Extending the findings with preschool children, these findings suggest that as children become older they become more responsive to conventional transgressions, and become more likely to actively maintain both moral and conventional rules/norms.

To examine the ontogenetic roots of children’s distinction between moral and conventional transgressions Smetana (1984) observed toddlers’ (13- to 40-months old) social interactions in daycare-center classrooms. Consistent with the work in preschool and school-aged children, moral transgressions were found to elicit responses from both caregivers and toddlers, whereas conventional transgressions only elicited a response from the caregivers. Interestingly, caregivers responded more frequently to moral transgressions with younger toddlers than older toddlers, and responded more frequently to conventional transgressions with older toddlers than younger toddlers. Caretakers responded to moral transgressions with a wide range of commands, physical restraint, and attempts to divert attention and the children who were the victims of the transgressions responded by emphasizing the harmful consequences of the transgression. However, caretakers responded to conventional transgressions most frequently with commands to stop the behavior and occasionally mentioned the concerns for social organization, such as rules and social norms.

The results of this study support the claim that moral and conventional events are conceptually unique and distinct in their origins, and that this distinction is evident in toddlers by the second year of life. Caretakers responded with a greater range of responses to moral than conventional transgressions, and provided explanations referencing the intrinsic harm and cost to the victim in contrast to conventional transgressions that were frequently left unexplained. It is also important to note, however, that many everyday social events are multifaceted, combining moral and conventional elements.

In both the home and the school setting, there are also many decisions that do not involve violations of regulations, but are rather personal choices up to the child. In the home context, Nucci and Weber (1995) examined child and maternal responses to personal (i.e. assertions of personal choice by the child), conventional, and moral issues. Mothers were found to vary their responses according to the type of event; personal issues were met with indirect messages such as offering choices, whereas moral and conventional issues were met with direct messages such as rule statements and commands. Mothers also negotiated with children more regarding personal issues than in response to moral and conventional issues. Children’s responses followed a similar line, in that children often protested for their choices regarding personal issues, but did not contest mothers’ responses to conventional and moral issues. Nucci and Weber argued that interactions regarding personal issues are critical to the child’s emerging sense of autonomy and are seen as a legitimate topic for indirect messages and negotiation between the mother and child, but that moral and conventional issues are not seen as relevant to building autonomy and are thus discussed with direct statements and commands.

To extend the findings of Nucci and Weber (1995) to examine the school context, Killen and Smetana (1999) observed preschool classrooms and conducted interviews with children regarding ongoing moral, conventional, and personal events. Killen and Smetana (1999) drew from previous literature to identify activities which it could be expected that adults would provide, or children would assert, personal choices during school, including what to do during activity time, what to eat and who to sit next to during lunch time, and where to sit during circle time (De Vries & Zan, 1994; Smetana & Bitz, 1996).

The findings revealed that social interactions regarding personal issues occurred more frequently in the preschool context than moral or conventional transgressions. This is an indication of the centrality of autonomy assertion during the preschool years (e.g., “I want to sit next to my friend, Sam!”). Further, consistent with the previous research reviewed, both children and teachers responded to moral transgressions, with adults focusing on the intrinsic consequences of events such as concerns for others’ rights and welfare. Similarly, teachers, but not children, were found to respond to conventional events, and did so by issuing commands and referring to the social order of the classroom, including school and classroom rules and norms.

As was also shown by Nucci and Weber (1995), adults (teachers) were more directive, issuing more commands and direct statements, regarding moral and conventional issues than personal issues, and were equally as likely to support or negate children’s assertions of personal choice. Differences were also found based on the specific context of the event; circle time was found to be a more conventionally structured setting than the other contexts, and moral transgressions were most likely to occur when classroom activities were less structured, such as during activity time. The contextual differences in occurrences of moral, conventional, and personal events between different school settings suggests that children develop an understanding that certain concerns are more relevant than others in each of the classroom settings, depending upon the degree of structure of each setting. Finally, in contrast to Nucci and Weber (1995), adults (teachers) rarely negotiated personal choices with children in the classroom. Teachers may be less inclined than mothers to negotiate these issues with children due to the generally more structured nature of the school than the home setting.

Overall, these social interaction and judgment studies provide evidence that children’s interactions are related to their judgments, and that not all rules are treated the same. Children as young as 3 years of age respond to, and evaluate rules that involve a victim, such as moral rules about not harming others or taking away resources are different from those that involve a regulation to make groups work well (such as where to play with toys or wearing a smock before painting a picture). Individuals believe that rules involving protection of victims are generalizable principles that are not a matter of consensus or authority; there are times when a group or authority may violate these principles and recognizing the independence of moral principles and group norms is a fundamental distinction that is necessary for successful interactions with other members of a community, a culture, or a society.

Research examining these distinctions has been validated through cross-cultural research in a range of countries, including North and South America (U.S. Canada, El Salvador, Mexico, Brazil, Colombia), Western Europe (U.K., Germany, The Netherlands, Spain), Asia (Korea, Japan, China, Hong Kong), Africa (Nigeria), Australia, and the Middle East (Israel, Jordan, Palestinian Territories); (for reviews, see Helwig, 2006; Turiel, 1998; Wainryb, 2006). In the next section, we review a major psychological requirement for making moral judgments-understanding intentionality and others’ mental states.

Morality and “theory of mind”

The psychological understanding of others’ mental states can often complicate moral judgments. During the preschool years, children are still slowly developing their ability to understand the mental states of others’- referred to as theory of mind (ToM) (Wellman & Liu, 2004). The ability to use intentionality judgments to make moral decisions has been shown to exist at the neurological level (Young & Saxe, 2008) and has only recently been examined at the level of explicit evaluation and judgments in children. To examine the link between ToM development and moral development, Smetana and colleagues (2012) examined the reciprocal associations between children’s developing ToM ability and their developing moral judgments in a longitudinal study. Participants were assessed on both their ToM ability and their moral judgments at three time points over one year (initial interview, 6-month follow up, and 12-month follow up), and ranged from 2- to 4-years-old at the initial interview. Moral judgments were assessed using four prototypic moral scenarios (hitting, shoving, teasing, and name calling) which were drawn from previous research. For each moral scenario participants responded to six questions, each assessing one of the core criteria of a moral judgment; nonpermissiblity, authority independence, rule independence, nonalterability, generalizability, and deserved punishment. Theory of mind was assessed using five ToM tasks; diverse desires, diverse beliefs, unexpected contents false beliefs, change of location false belief, and belief emotion.

Different patterns were found for each of the criterion questions, suggesting a reciprocal relationship between the development of ToM and moral judgment. Participants who judged the moral transgressions as more wrong independent of authority had a more advanced ToM ability 6-months later, for both wave 1 and wave 2. Similarly, participants who judged the moral transgression as more impermissible had a more advanced ToM ability 6-months later for the second wave. These findings suggest that children’s attempts to understand social relationships and events may influence their later ToM ability. Conversely, results indicated that a more sophisticated ToM ability led to less prototypic moral judgments 6-months later for other criterion questions. Participants viewed all of the moral transgressions as nonpermissible, authority and rule independent, nonalterable, generalizably wrong, and deserving of punishment. Taken together, these results suggest that ToM and moral judgments develop as bidirectional, transactional processes (Smetana et al., 2012). Early experiences interpreting moral transgressions influence the development of ToM and the ability to understand the mental states of others allows for a more complex understanding of moral scenarios.

One aspect of children’s attributions of intentionality and moral judgment not addressed by these findings, however, is children’s understanding of unintentional moral transgressions, and their attributions of intentions in these contexts. A recent investigation of intentionality and moral judgment conducted by Killen, Mulvey, Richardson, Jampol, and Woodward (2011) investigated whether 3-, 5-, and 7-year-old children’s (N = 162) ToM competence was related to their attributions of intentions and moral judgments of unintentional transgressions. The investigators presented participants with a series of tasks, including prototypic contents and location change false-belief ToM tasks, a prototypic moral transgression (pushing someone off a swing), and a morally relevant theory of mind task (MoToM). The MoToM task was a story vignette in which a child brought a special cupcake in a paper bag to lunch. Then, as the child left for recess, a classroom helper entered the room and threw away the paper bag. Thus, the classroom helper threw away the lunch bag while helping to clean up the room. The MoToM measure assessed morally relevant embedded contents false belief (What did X think was in the bag?), evaluation of the act (Did you think it was all right or not all right?), attribution of the accidental transgressors’ intentions (Did X think she was doing something all right or not all right?), and punishment (Should X be punished?). Reasoning was also obtained for these assessments (e.g., Why?). Participants who correctly responded that the classroom helper thought there was only trash in the bag passed the MoToM assessment.

Killen and colleagues (2011) found that while children reliably passed the prototypic contents false-belief ToM task by 5-years-old, children did not reliably pass the MoToM task until around 7-years-old. This indicates that the saliency of a moral transgression can influence younger children’s social cognition regarding other’s mental states.

Additionally, it was found that children who failed the MoToM task were more likely to attribute negative intentions and ascribe punishment to the unintentional transgressor than were children who passed the MoToM task. These finding show that children who do not possess MoToM competency do not understand the unintentional nature of the transgression, and thus attribute negative intentions to, and harsher moral judgments of, transgressors, whereas children who do possess MoToM competency understand that the transgression was unintentional and do not attribute negative intentions to the unintentional transgressor, and do not view the act as wrong.

These findings reveal that as children’s understanding of personal/psychological concerns regarding others mental states (intentions) develops, their moral judgments become more complex, in that they can incorporate mental state information into their attributions of intentionality and moral judgments. In the next section, we examine how group identity and intergroup attitudes presents a new challenge for the application of morality to social interactions and social life.

Morality and intergroup attitudes

Reasoning about social exclusion involves the moral concerns of fairness and equality, as well as concerns about group functioning, group identity, and, along with these concepts, stereotypes about outgroup members. Drawing on research in social psychology on group identity (Abrams, Hogg, & Marques, 2005), developmental researchers have more closely examined how group identity plays a role when applying fairness judgments to social exclusion. This research contrasts with research on interpersonal rejection which identifies the personality deficits of a group member rather than group membership (Killen, Mulvey, & Hitti, 2013). While peer rejection can result from interpersonal deficits, in many cases exclusion occurs due to biases and dislike of outgroup members. Examining intergroup exclusion reflects a new line of research from a developmental perspective.

Developmental intergroup research has shown the myriad ways in which very young children hold implicit biases towards others, even in minimal group contexts in which laboratory generated categories are created (Dunham, Baron, & Carey, 2011). Children’s affiliations with groups enables them to hold a group identity which often is reflected by an ingroup preference (Nesdale, 2004). While ingroup preference does necessarily lead to outgroup dislike, this is often the unfortunate outcome of an ingroup bias which has also been documented in childhood (Bigler, Brown, & Markell, 2001). Group identity can be measured many ways (see Rutland, Levy, & Abrams, 2007), from implicit to explicit forms. Implicit forms refer to when children demonstrate an ingroup bias unbeknownst to them; explicit forms refer to statements in which children articulate a preference for their own group. In a series of studies, researchers have investigated whether children apply moral judgments to group identity preferences, that is, to what extent do they explicitly condone ingroup preference, and when do they view it as unfair?

As one illustration, to investigate how children applied moral concerns about exclusion in stereotypic contexts, Killen, Pisacane, Lee-Kim, and Ardila-Rey (2001) studied preschool aged children’s (N = 72) application of fairness judgments in gender stereotypic contexts. The situations involved a boys’ group excluding a girl from truck-playing and a girls’ group excluding a boy from doll-playing. There were two conditions for a within-subjects design. In the straightforward condition, children were asked if it was all right to exclude the child who did not fit the stereotype. The majority (87%) of children stated that it was unfair and gave moral reasons (“The boy will feel sad and that’s not fair”; “Give the girl a chance to play –they’re all the same.”).

To create a condition with increased complexity, children were told that two peers wanted to join the group, a boy and a girl, and there was only room for one more to join. Then, they were asked whom should the group pick? In this condition, children were split in their decision, often resorting to stereotypic expectations (“Pick the girl because dolls are for girls.”; “Only boys know how to play with trucks.”). Children who started out with a fairness judgment did not change their minds after hearing a counter-probe (“But what about the other child?”), whereas children who started out with a stereotypic decision were more likely to change their judgment, and pick the child who did not fit the stereotype. These findings illustrated that children apply moral judgments to contexts involving group identity but often have difficulties when the situation get complicated. Social psychologists find this pattern as well with adults to the extent that adults resort to stereotypic expectations in situations with complexity or ambiguity (Dovidio, Kawakami, & Beach, 2001).

Developmental researchers have also examined exclusion of ingroup members who challenge the norms of the group, and whether this varies by moral or conventional norms (Killen, Rutland, Abrams, Mulvey, & Hitti, 2013). Children and adolescents evaluated group inclusion and exclusion in the context of norms about resource allocation (moral) and club shirts (social conventional). Participants (N = 381), aged 9.5 and 13.5 years, judged an ingroup member’s decision to deviate from the norms of the group, whom to include, and whether their personal preference was the same as what they expected a group should do. The findings revealed that participants were favorable towards ingroup members who deviated from unequal group norms to advocate for equal distributions, even when it went against the group norm. Moreover, they were less favorable to ingroup members who advocated for inequality when the group wanted to distribute equally (see Figure 3). The same was true, but less so, for ingroup members who challenged the norms about the club shirts.

Figure 3.

Evaluation of the deviant act by condition and age (1 =really not okay; 6 =really okay) from Killen, Rutland, Abrams, Mulvey, & Hitti, 2013 (reprinted from Child Development)

The novel findings were that children and adolescents did not evaluate ingroup deviance the same across all contexts; the type of norm mattered, revealing the importance of norms about fairness and equality. In subsequent analyses using the same paradigm, researchers asked children about exclusion of deviant ingroup members, and found that exclusion of deviant members was viewed as increasingly wrong with age, and yet, participants who disliked deviants found it acceptable to exclude them (such as an ingroup member who wanted to distribute unequally (Hitti, Mulvey, Rutland, Abrams, & Killen, in press). Further, Mulvey and colleagues (in press) found that with age, participants differentiated their own favorability from the group’s favorability; with age, children expected that groups would dislike members who deviated from the group, revealing an aspect of mental state knowledge (that the group would dislike an ingroup member who challenged the group norm even though they would like this member). Overall, the results provide a developmental story about children’s complex understanding of group dynamics in the context of moral and social norms. While space does not permit a more exhaustive review of how children apply moral concepts to intergroup attitudes (for a review, see Killen & Rutland, 2011), research from multiple theoretical approaches have investigated how moral judgments and emotions are revealed in children’s intergroup attitudes (see Heiphetz & Young, this volume).

Conclusions

In summary, the emergence of morality is a long, slow, complex process, which originates early in development and continues throughout life. Infants appear to prefer others who are helpful and have positive intentions towards others. Peer interactions launch the first set of social conflicts that children experience during early childhood. These conflicts, we argue, do not merely reflect a moral versus “selfish” orientation, but are multifaceted. Children’s knowledge about groups and group identity conflict with moral goals of fairness; as well, attributions of intentions curtail children’s accurate reading of blame, responsibility, and accountability. Further, constructive and positive opportunities to resolve conflicts enables children to develop an understanding of mental states, which along with emerging negotiation and reciprocal social skills, provides the pathway for the development of morality. From childhood to adulthood, moral conflicts become increasingly complicated and multifaceted. Friendships with members of outgroups helps to reduce outgroup bias (Tropp & Prenovost, 2008), and to better understanding the application of intentions to others (Carpendale & Lewis, 2006).

The documentation of sociality reveals the roots for morality. We believe that there is an evolutionary basis to this phenomenon. Non-human primates respond to the distress of another, reject unfair distributions of resources, demonstrate prosocial behavior, and resolve conflicts in non-aggressive ways (Brosnan, Talbot, Ahlgren, Lambeth, & Schapiro, 2010; de Waal, 2006). This evolutionary past reveals the building blocks for morality in humans. Understanding this complex process enables humans to better reflect on their own morality, and to identify the strategies that appropriately facilitate the development of moral judgment.

Fig. 2.

Judgments about intentions and acts in a morally relevant context. Killen, Mulvey, Richardson, Jampol & Woodward, 2011 (Reprinted from Cognition).

Acknowledgements

We thank Frans de Waal, Telmo Pievani, and Stefano Parmigiani, the organizers of the “The evolution of morality: The biology and philosophy of human conscience” workshop, held at the beautiful Ettore Majorana Foundation and Centre for Scientific Culture in Erice, Sicily, June, 2012, for creating a stimulating interdisciplinary context for discussions of morality. We are appreciative of the feedback on the manuscript from Kelly Lynn Mulvey and two anonymous reviewers, and to Shelby Cooley, Laura Elenbaas, Aline Hitti, Kelly Lynn Mulvey, and Jeeyoung Noh for collaborations related to the research described in this manuscript.

This research was supported by a grant award from the National Science Foundation (DLS, #0840492): to the first author, and a NICHD funded T32 award for the second author (#HD007542).

References

- Abrams D, Hogg M, Marques J. The social psychology of inclusion and exclusion. Psychology Press; New York: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Abrams D, Rutland A. The development of subjective group dynamics. In: Levy SR, Killen M, editors. Intergroup relations and attitudes in childhood through adulthood. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 2008. pp. 47–65. [Google Scholar]

- Bigler RS, Brown CS, Markell M. When groups are not created equal: Effects of group status on the formation of intergroup attitudes in children. Child Development. 2001;72:1151–1162. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosnan SF, Talbot C, Ahlgren M, Lambeth SP, Schapiro SJ. Mechanisms underlying responses to inequitable outcomes in chimpanzees, Pan troglodytes. Animal Behaviour. 2010;79(6):1229–1237. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2010.02.019. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2010.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownell C, Carriger M. Collaborations among toddler peers: Individual contributions to social contexts. In: Resnick LB, Levine JM, Teasley SD, editors. Perspectives on socially shared cognition. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 1991. pp. 365–383. [Google Scholar]

- Brownell CA, Ramani GB, Zerwas S. Becoming a social partner with peers: Cooperation and social understanding in one- and two-year-olds. Child Development. 2006;77(4):803–821. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00904.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00904.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpendale J, Lewis C. How children develop social understanding. Blackwell Publishing; Oxford, U.K.: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy J. The nature of the child's ties. In: Cassidy J, Shaver PR, editors. Handbook of attachment: Theory, research and clinical applications. 2nd Guilford Publishers; New York: 2008. pp. 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Churchland P. Braintrust: What neuroscience tells us about morality. Princeton University Press; Princeton, NJ: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cords M, Killen M. Conflict resolution in human and nonhuman primates. In: Langer J, Killen M, editors. Piaget, evolution, and development. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; Mahwah, NJ US: 1998. pp. 193–218. [Google Scholar]

- Dahl A, Schuck RK, Campos JJ. Do young toddlers act on their social preferences? Developmental Psychology. 2013 doi: 10.1037/a0031460. doi: 10.1037/a0031460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darwin C. The descent of man. Penguin Classics; London: 1871/2004. [Google Scholar]

- de Waal FBM. Good natured: The origins of right and wrong in humans and other animals. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- de Waal FBM. Primates and philosophers: How morality evolved. Princeton University Press; Princeton, NJ US: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- de Waal FBM. Natural normativity: The "is" and "ought" of animal behavior. Behaviour. this issue. [Google Scholar]

- DeVries R, Zan B. Moral classrooms, moral children. Teachers College Press; New York: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Dovidio JF, Kawakami K, Beach K. Implicit and explicit attitudes: Examination of the relationship between measures of intergroup bias. In: Brown R, Gaertner SL, editors. Blackwell handbook of social psychology. Vol. 4. Blackwell Publishers; Oxford, England: 2001. pp. 175–197. [Google Scholar]

- Dunham Y, Baron AS, Carey S. Consequences of 'minimal' group affiliations in children. Child Development. 2011;82(3):793–811. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01577.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01577.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freud S. Civilization and its discontents. W.W.Norton & Company, Inc.; NY: 1930/1961. [Google Scholar]

- Gewirth A. Reason and morality. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Hamlin JK, Wynn K, Bloom P. Social evaluation by preverbal infants. Nature. 2007;450:557–560. doi: 10.1038/nature06288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heiphetz L, Young L. A social cognitivie developmental perspective on moral judgment. Behaviour. this volume. [Google Scholar]

- Helwig CC. Rights, civil liberties, and democracy across cultures. In: Killen M, Smetana JG, editors. Handbook of moral development. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, NJ: 2006. pp. 185–210. [Google Scholar]

- Hitti A, Mulvey KL, Rutland A, Abrams D, Killen M. When is it okay to exclude a member of the ingroup?: Children's and adolescents' social reasoning. Social Development. in press. [Google Scholar]

- Kant I. Foundations of the metaphysics of morals. Bobbs-Merrill; New York: 1785/1959. [Google Scholar]

- Killen M, Mulvey KL, Hitti A. Social exclusion in childhood: A developmental intergroup perspective. Child Development. 2013;84:772–790. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12012. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killen M, Mulvey KL, Richardson C, Jampol N, Woodward A. The accidental transgressor: Morally-relevant theory of mind. Cognition. 2011;119(2):197–215. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2011.01.006. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killen M, Pisacane K, Lee-Kim J, Ardila-Rey A. Fairness or stereotypes? Young children's priorities when evaluating group exclusion and inclusion. Developmental Psychology. 2001;37(5):587–596. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.37.5.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killen M, Rutland A. Children and social exclusion: Morality, prejudice, and group identity. Wiley/Blackwell Publishers; New York, NY: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Killen M, Rutland A, Abrams D, Mulvey KL, Hitti A. Development of intra- and intergroup judgments in the context of moral and social-conventional norms. Child Development. 2013;84:1063–1080. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12011. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killen M, Smetana JG. Social interactions in preschool classrooms and the development of young children’s conceptions of the personal. Child Development. 1999;70:486–501. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhlmeier V, Bloom P, Wynn K. Attribution of dispositional states by 12-month-olds. Psychological Science. 2003;14:402–408. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.01454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulvey KL, Hitti A, Cooley S, Abrams D, Rutland A, Ott J, Killen M. Adolescents’ ingroup bias: Gender and status differences in adolescents’ preference for the ingroup; Paper presented at the Society for Research Adolescence; Vancouver, BC. in press. [Google Scholar]

- Mulvey KL, Hitti A, Killen M. Morality, intentionality, and exclusion: How children navigate the social world. In: Banaji M, Gelman S, editors. Navigating the social world: A developmental perspective. Oxford University Press; NY: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Nesdale D. Social identity processes and children’s ethnic prejudice. In: Bennett M, Sani F, editors. The development of the social self. Psychology Press; New York: 2004. pp. 219–245. [Google Scholar]

- Nucci LP, Nucci MS. Children's responses to moral and social-conventional transgressions in free-play settings. Child Development. 1982;53:1337–1342. [Google Scholar]

- Nucci LP, Turiel E. Social interactions and the development of social concepts in preschool children. Child Development. 1978;49(2):400–407. doi: 10.2307/1128704. [Google Scholar]

- Nucci LP, Weber EK. Social interactions in the home and the development of young children's conceptions of the personal. Child Development. 1995;66:1438–1452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Over H, Carpenter M. Eighteen-month-old infants show increased helping following priming with affiliation. Psychological Science. 2009;20:1189–1193. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piaget J. The moral judgment of the child. Free Press; New York: 1932. [Google Scholar]

- Rawls J. A theory of justice. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Sen AK. The idea of justice. Harvard University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rutland A, Abrams D, Levy SR. Extending the conversation: Transdisciplinary approaches to social identity and intergroup attitudes in children and adolescents. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2007;31:417–418. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner BF. About behaviorism. Vintage Books, INC.; NY: 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Smetana JG. Toddlers' social interactions regarding moral and social transgressions. Child Development. 1984;55:1767–1776. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smetana JG. Social-cognitive domain theory: Consistencies and variations in children's moral and social judgments. In: Killen M, Smetana JG, editors. Handbook of moral development. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, NJ: 2006. pp. 119–154. [Google Scholar]

- Smetana JG. Adolescents, families, and social development: How teens construct their worlds. Wiley/Blackwell; New York, NY: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Smetana JG, Bitz B. Adolescents' conceptions of teachers' authority and their relations to rule violations in school. Child Development. 1996;67:202–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smetana JG, Jambon M, Conry-Murray C, Sturge-Apple M. Reciprocal associations between young children's moral judgments and their developing theory of mind. Developmental Psychology. 2012;48(4):1144–1155. doi: 10.1037/a0025891. doi: 10.1037/a0025891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RA. The development of the person: Social understanding, relationships, conscience, self. In: Eisenberg N, editor. Handbook of child psychology: Social, Emotional, and Personality Development. Vol. 3. Wiley & Sons, Inc.; NY: 2006. pp. 24–98. [Google Scholar]

- Tropp LR, Prenovost MA. The role of intergroup contact in predicting children's inter-ethnic attitudes: Evidence from meta-analytic and field studies. In: Levy SR, Killen M, editors. Intergroup attitudes and relations in childhood through adulthood. 236-248. Oxford University Press; Oxford, U.K.: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Turiel E. The development of social knowledge: Morality and convention. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, England: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Turiel E. The development of morality. In: Damon W, editor. Handbook of child psychology. 5th. Vol. 3. Wiley; New York: 1998. pp. 863–932. Social, emotional, and personality development. [Google Scholar]

- Verbeek P, Hartup W, Collins WA. Conflict management in children and adolescents. In: Aureli F, de Waal FDM, editors. Natural Conflict Resolution. University of California Press; Berkeley, CA: 2000. pp. 34–53. [Google Scholar]

- Wainryb C. Moral development in culture: Diversity, tolerance, and justice. In: Killen M, Smetana JG, editors. Handbook of moral development. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, NJ: 2006. pp. 211–240. [Google Scholar]

- Warneken F, Hare B, Melis A, Hanus D, Tomasello M. Spontaneous altruism by chimpanzees and young children. PLOS Biology. 2007;5:e184. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warneken F, Tomasello M. Altruistic helping in human infants and young chimpanzees. Science. 2006;311(5765):1301–1303. doi: 10.1126/science.1121448. doi: 10.1126/science.1121448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warneken F, Tomasello M. Extrinsic rewards undermine altruistic tendencies in 20-month-olds. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44:1785–1788. doi: 10.1037/a0013860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellman HM, Liu D. Scaling of theory-of-mind tasks. Child Development. 2004;75:502–517. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams B. Moral luck. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Wimmer H, Perner J. Beliefs about beliefs: Representation and constraining function of wrong beliefs in young children's understanding of deception. Cognition. 1983;13(1):103–128. doi: 10.1016/0010-0277(83)90004-5. doi: 10.1016/0010-0277(83)90004-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodward AL. Infants grasp of others intentions. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2008:1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01605.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodward AL. Infants' learning about intentional action. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 2009. [Google Scholar]