Abstract

Myiasis is the condition of infestation of the body by fly larvae (maggots). The deposited eggs develop into larvae, which penetrate deep structures causing adjacent tissue destruction. It is an uncommon clinical condition, being more frequent in tropical countries and hot climate regions, and associated with poor hygiene, suppurative oral lesions, alcoholism and senility. The diagnosis of Myiasis is basically made by the presence of larvae. The reported cases of oral Myiasis associated with oral cancer in the literature are few. This paper reports two cases of oral and maxillofacial Myiasis involving larvae in patients with squamous cell carcinoma in adult males. The condition was managed by manual removal of the larvae, one by one, with the help of forceps and subsequent management through proper health care.

Keywords: Larvae, maggots, oral Myiasis, squamous cell carcinoma

INTRODUCTION

Tissues of the oral cavity can be invaded by parasitic larvae of house flies; this condition is called as oral Myiasis. The term Myiasis was coined by Hope in 1840[1] and it is derived from Greek word “myia” meaning fly. It was first described by Laurence in 1909.[1] It was defined by Zumpt as the infestation of live human and vertebrate animals with dipterous larvae, which feed on living or dead host tissue, liquid body substance or ingested food for a certain period of time.[2] Human Myiasis is a rare condition that can occur in any part of the globe, but is more common in regions with a warm and humid climate.[3] Higher incidence is reported in tropical, subtropical regions of Africa, America, and South East Asia, where warm, humid climate prevail almost throughout the year; commonly seen among people where sanitation, personal hygiene is often ignored and close association with domestic pets exists.[4] The infestations can strike organs or tissues that are accessible to egg-laying and development of the larvae, which feed on living or necrotic tissue and body fluids, and necrotic lesions that provide an ideal substrate.[3]

Diabetes, immunosuppression and peripheral vascular diseases can be predisposing factors for Myiasis, mainly in elderly, in whom the sites most attacked are the feet and ankles. The condition can be completely benign and asymptomatic, resulting in pain or in extreme cases cause death of the patient.[5]

They may infest different parts of the body as in cutaneous, urogenital, ophthalmic, nasopharyngeal, intestinal, and the oral cavity.[3] Oral Myiasis is more commonly ascribed to predisposing anatomical, medical conditions where oral cavity is being exposed to the external environment for a prolonged time, mouth breathing, anterior open bite, incompetent lips, cerebral palsy, following tooth extractions, neglected mandibular fracture, patients undergoing mechanical ventilation, and certain local pathological conditions such as cancrum oris, and oral malignancies.[4]

This paper presents two cases of oral Myiasis associated with squamous cell carcinoma.

CASE REPORTS

Case 1

A 50-year-old male patient was reported to the Department of Oral Medicine and Radiology with the complaint of pain and swelling on the right side of the face since 15 days. Patient noticed an ulcer on the right buccal mucosa 4 months ago which progressed to involve the complete right buccal mucosa, including vestibule and alveolar ridge. Severe pain and burning sensation was experienced by the patient since past 15 days. Patient gave a history of exfoliation of two teeth from the same region, 2 weeks ago. He also noticed two extraoral wounds with blood and pus discharge since then. Past medical and family history was not significant.

On extraoral examination, there was diffuse swelling on the right side of the face, extending vertically from right inferior orbital rim to the inferior border of mandible and horizontally from right ala of the nose to angle of mandible. Two extraoral ulcers were seen [Figure 1] with blood and pus discharge. The overlying skin was reddish in color. The swelling was firm and tender on palpation. Few maggots were seen coming out of the ulcers. Bilateral submandibular and submental lymph nodes were enlarged, fixed, firm, and tender.

Figure 1.

Clinical photograph showing two extraoral deep necrotic ulcers on the right side

On intraoral examination, an ulceroproliferative lesion was seen involving the complete right buccal mucosa, vestibule and extending to the alveolar ridge. Profuse bleeding was seen from the lesion.

Orthopantomograph showed irregular bone destruction extending from 44 to 48 and soft-tissue shadow was seen, which were suggestive of a malignant lesion [Figure 2]. Depending on the history, clinical and radiographic features and presence of maggots, the provisional diagnosis of malignant tumor with Myiasis infestation was made.

Figure 2.

Orthopantomograph showing irregular bone destruction from 44 to 48 with floating tooth appearance with 44, 45

Mechanical removal of larvae was done using turpentine oil along with surgical debridement of necrotic tissue [Figure 3]. The wound was debrided for next 5 consecutive days and all of the maggots were removed. Systemic antibiotics, Augmentin 625 mg (amoxicillin + clavulanic acid) 3 times a day for 7 days, metronidazole 400 mg 3 times a day for 5 days and 0.2% chlorhexidine antiseptic mouthwash, were prescribed for 7 days.

Figure 3.

Removed maggots (Case 1)

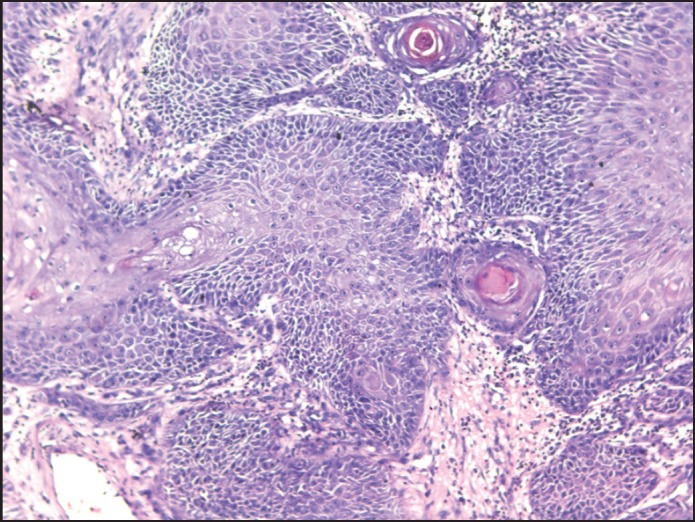

The incisional biopsy was done on the 5th day and histopathologically, the section showed, stratified squamous epithelium with proliferation. The connective tissue was invaded by tumor, showing malignant epithelial cells with large hyperchromatic pleomorphic nucleus and a moderate amount of cytoplasm. Keratin pearl formation was also noted at places. The stroma showed dense inflammatory cells predominantly lymphocytes and plasma cells. Overall features were of well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma [Figure 4].

Figure 4.

Well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (×10). Section showing connective tissue infiltration by tumor cells and keratin pearls (Case 1)

The patient was referred to Oncology Department of the same institute for radiotherapy. Patient had undergone 15 cycles of radiotherapy and did not return for further treatment and follow-up.

Case 2

A 55-year-old male patient belonging to a rural area and low socio-economic status was reported to our department with an extensive facial wound on the left side of the face and live worms since 1 month. Patient noticed a small ulcerative lesion on the left side of buccal mucosa 7 months back that progressively increased to involve the complete left buccal mucosa and left floor of the mouth, with extraoral ulceration, pus discharge and pain since 2 months. Patient noticed rapid increase in the ulceration with destruction of the overlying skin, severe pain and worms in the same region since 1 month.

On clinical examination, the patient appeared malnourished, weak with cachexic built. Medical and dental history was not significant. On extraoral examination, a large necrotic wound was seen, with complete through and through destruction of the overlying skin and mucosa, exposing the mandible and part of maxilla, along with crawling maggots [Figure 5]. The necrotic wound was extending superiorly from approximately 2 cm below the left infraorbital rim, inferiorly to the inferior border of the mandible, anteriorly from the midline and posteriorly 2 cm anterior to the posterior border of the mandible. Diffuse swelling was seen on the complete left side of the face, along with periorbital edema, causing closure of the left eye. The bilateral submandibular, submental and cervical chains of lymph nodes were enlarged, fixed, firm, and non-tender. Depending on the history and clinical presentation, the case was diagnosed as malignancy with oral Myiasis.

Figure 5.

Extensive necrotic wound with maggots

The treatment began with the flushing of the wound with turpentine oil. Around 60 maggots were removed [Figure 6] one by one using tweezers and the wound was irrigated with saline, followed by the placement of dressing. The patient was prescribed antibiotics, Augmentin 625 mg (amoxicillin + clavulanic acid) three times a day for 7 days, metronidazole 400 mg three times a day for 5 days, and 0.2% chlorhexidine antiseptic mouthwash, for 7 days, and was recalled after 24 hrs for repeat debridement, removal of larvae and incisional biopsy.

Figure 6.

Removed maggots (Case 2)

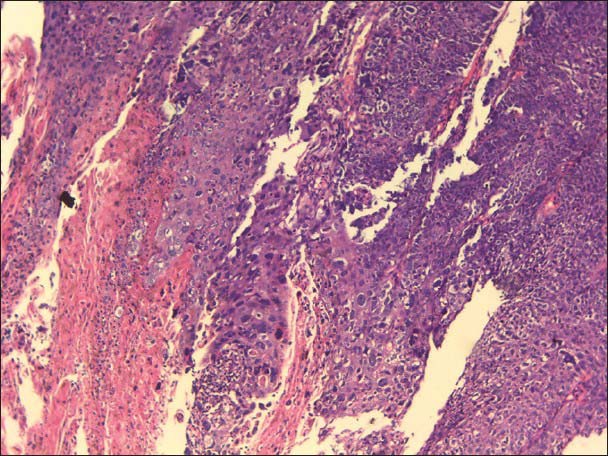

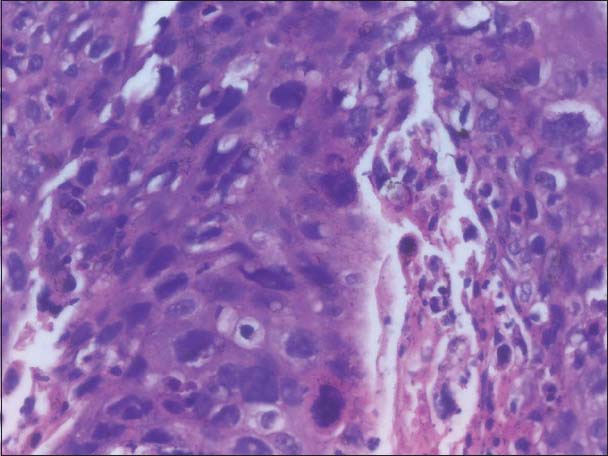

The incisional biopsy was done and H and E stained section of the tissue exhibited surface epithelium, which was of parakeratinized stratified squamous type. The underlying connective tissue exhibited tumor cells with very little resemblance to the squamous epithelial cells. Most of the cells were highly anaplastic, less cohesive and were actively invading in the connective tissue in a vigorous pattern. The individual cells were large, round to polyhedral in shape and exhibited a high degree of cellular and nuclear pleomorphism. The nuclei were hyperchromatic and at places were large, round, often vesicular and exhibited prominent or even multiple nucleoli. Abnormal mitotic figures were also observed. Individual cell keratinization and epithelial pearl formation were lacking. The stroma exhibited very little or no lymphocytic infiltration. The histopathological features were suggestive of poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma [Figures 7a and b].

Figure 7a.

Poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (×10). Section showing tumor epithelial cells infiltrating the stroma (Case 2)

Figure 7b.

Same tumor at high power showing tumor cells with anaplastic features (Case 2)

The patient was recalled for treatment, but did not return for further treatment and follow-up.

DISCUSSION

Myiasis of orodental complex is a rare entity. Oral Myiasis may present as an oral mucosal swelling, gum swelling, periodontal disease, palatal ulcerations, secondary infestation of cancrum oris, in oral wounds such as extraction wound, jaw bone fractures, oral leprosy lesion and malignancies.[6] The risk factors for the development of Myiasis are suppurative lesions, open wounds, scabs, traumatic wounds, ulcers contaminated with discharges and blood remnants (necrotic). When these conditions are superimposed with debilitation, mental or physical disability and poverty, the chances of Myiasis increases.[3] The patients in the present cases were of low socio-economic status having poor living conditions. Besides, the population who lives in rural areas often neglect their health, sometimes simply due to lack of knowledge. This situation can be observed in the present cases as they had clinically advanced stage of the malignancy. In addition, infrastructure and other facilities are inadequate, and overall quality of life is poor.[3] The association of Myiasis with oral malignancy can be explained as the fungating and necrotic wounds are common among cancer patients in India because many patients have advanced neglected tumors because of low socio-economic status and lack of knowledge.[3,7,8] Necrotic and decomposing tissue, and poor oral hygiene, attracts flies, with India's tropical climate being especially conducive to their breeding. Since proper oral hygiene and hygiene of the surrounding is not maintained by the oral cancer patients as well as the care givers, and other predisposing factors such as the advancing age, alcoholism, diabetes and other systemic conditions exist, the risk for oral Myiasis increases.[9] Advanced disease in the head and neck cancer is often associated with the occurrence of disseminated regional and distant metastases. At this stage of the disease the point of incurability will be reached when effective treatment options have all been tried or are regarded as ineffective, or the treatment itself had been neglected by the patient. Soon the disease gets out of control, with subsequent unstoppable progression of cancer. From experience, it is known that many of the affected patients develop extensive cutaneous or head and neck metastases in this situation, which may grow, fungating and exophytically. If wound care and dressing changes at this stage are inadequate and only sporadically performed, the affected patients are at risk of developing severe superinfections from different origins (e.g., bacteriological, parasitological). Thus, unpleasant odorous secretions are likely to result. This kind of tissue, i.e., the pre-existing lesion and the fetid odor along with the above mentioned predisposing factors, is attractive to different species of flies, which may deposit their eggs in this medium, especially in the spring and summer months.[10]

Extensive oral Myiasis infestation associated with squamous cell carcinoma in the head and neck region are reported in the literature, but are very few.[3,7,8,11,12,13,14] Sesterhenn et al.[10] have reported occurrence of Myiasis in cutaneous metastasis of oropharyngeal cancer and reviewed 20 cases of cutaneous Myiasis in malignant wounds resulting from primary cancer of the head and neck area. Cases were predominantly associated with squamous or basal cell cancer of the skin. Yaghoobi and Bagherani[14] have reported a case of Myiasis in epidermoid carcinoma on the face and counted four more cases of skin cancers associated with Myiasis in the medical literature. Lefkowits[15] has reported another case of cutaneous Myiais in a malignant wound of face.

Yadav et al.[3] reported Myiasis infestation in treated squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue. Pessoa and Galvavo[11] reported Myiasis infestation in advanced oral squamous cell carcinoma and Dharshiyani et al.[12] reported another case of Myiasis in oral squamous cell carcinoma.

Myiasis is caused by members of the Diptera fly family that lay eggs on food, necrotic tissue, open wounds, and unbroken skin or mucosa.[16] It is commonly caused by common Indian housefly Musca Nebulo.[4] The three main families of flies involved in Myiasis are the Calliphordiae (timbu flies, screwworms, greenbottles and bluebottles), Sarcophagidae (flesh fly) and Oestridae (warble flies and botfly).[9]

The lifecycle of a fly commences with egg stage followed by the larval stage, the pupal stage, and finally the adult fly.[4] The stage of larvae lasts for 6-8 days during which they are parasitic to human beings. They are photophobic and tend to hide into the tissues for suitable niche to develop into pupa.[2] These larvae release toxins to destroy the host tissue. Proteolytic enzymes released by the surrounding bacteria decompose the tissue and the larvae feed on this rotten tissue. The infected tissue frequently releases a foul smelling discharge.[2] This similar finding of condition of foul smelling discharge of blood and pus was seen in the first case of this report.

The standard treatment options include maintenance of nutrition, antimicrobials for secondary infection, manual removal of larvae and thorough cleaning of the wound. Chemical substances are used to promote larval asphyxia and inducing them to exit out of the wound.[17,18]

The other topical agents which can be used are ether, chloroform, olive oil, calomel, iodoform, and phenol mixture.[2,17,18] In the present cases, elimination of the maggots was achieved with turpentine oil and the patients were administered systemic antibiotics.

Ivermectin is a semisynthetic macrolide antibiotic isolated from streptomyces avermitilis and its use is well-documented in large animals for the control of gastrointestinal and pulmonary parasitosis for infestation by crab louse and larva flies (“berne”).

Ivermectin was reported to be safe for human use in 1993 and has been indicated for the treatment of filaria, scabies, strongyloidiasis and Myiasis. The ivermectin acts by blocking the nerve endings through the release of gamma amino butyric acid leading to palsy and causes parasitic death and spontaneous elimination by washing out of the larvae thus avoiding mechanical removal and achieving lower morbidity. The ivermectin was used in doses of 6 mg orally once daily for 2 days in few cases reported in literature and authors found them effective and safe.[3,18,19] Ivermectin given orally in just one dose of 150-200 mcg/kg body weight and repeated after 24 hrs has been reported to be effective in severe cases.[19] In these presented cases, ivermectin was not prescribed due to the unavailability of the drug since it is a rural area and also the standard treatment protocol of removal of maggots and surgical debridement of the wounds, is being followed by our institution. Secondary bacterial infection along the surrounding skin should be treated with antibiotics. Patient's diet should be supplemented with multivitamins, mineral and nutrients.[17]

CONCLUSION

There is an old saying “Prevention is better than cure.” The best method of prevention of Myiasis in humans is by education. The disease can be prevented by controlling the fly population, maintaining good oral and personal hygiene such as reducing the decomposition odor, cleaning and covering the wounds and by educating the population where basic sanitation is meager. Special care needs to be taken in medically compromised, dependent patients as they are unable to maintain their basic oral hygiene. Myiasis is generally self-limiting and in many cases not dangerous to the host. If caught in the initial stage, one can prevent involvement of deeper tissues, consequently avoiding greater suffering by the patient during treatment.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rao KB, Prasad S. Oral myiasis: A case report. Ann Essences Dent. 2010;2:204–7. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sharma J, Mamatha GP, Acharya R. Primary oral myiasis: A case report. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2008;13:E714–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yadav SK, Shrestha S, Sah AK. Extensive myiasis infestation over a malignant lesion in maxillofacial region: Report of cases. Int J Pharm Biol Arch. 2012;3:530–3. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhola N, Jadhav A, Borle R, Adwani N, Khemka G, Jadhav P. Primary oral myiasis: A case report. Case Rep Dent 2012. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/734234. 734234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rossi-Schneider T, Cherubini K, Yurgel LS, Salum F, Figueiredo MA. Oral myiasis: A case report. J Oral Sci. 2007;49:85–8. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.49.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yeung KH, Leung AC, Tsang AC. Oral myiasis. Hong Kong Dent J. 2004;1:35–6. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gabriel JG, Marinho SA, Verli FD, Krause RG, Yurgel LS, Cherubini K. Extensive myiasis infestation over a squamous cell carcinoma in the face. Case report. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2008;13:E9–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carvalho RW, Santos TS, Antunes AA, Laureano Filho JR, Anjos ED, Catunda RB. Oral and maxillofacial myiasis associated with epidermoid carcinoma: A case report. J Oral Sci. 2008;50:103–5. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.50.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sowani A, Joglekar D, Kulkarni P. Maggots: A neglected problem in palliative care. Indian J Palliat Care. 2004;10:27–9. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sesterhenn AM, Pfützner W, Braulke DM, Wiegand S, Werner JA, Taubert A. Cutaneous manifestation of myiasis in malignant wounds of the head and neck. Eur J Dermatol. 2009;19:64–8. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2008.0568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pessoa L, Galvão V. Myiasis infestation in advanced oral squamous cell carcinoma. BMJ Case Rep. 2011 doi: 10.1136/bcr.04.2011.4124. published online 15 July 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dharshiyani SC, Wanjari SP, Wanjari PV, Parwani RN. Oral squamous cell carcinoma associated with myiasis. BMJ Case Rep. 2012 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2012-007178. published online 23 December 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gopalakrishnan S, Srinivasan R, Saxena SK, Shanmugapriya J. Myiasis in different types of carcinoma cases in southern India. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2008;26:189–92. doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.40542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yaghoobi R, Bagherani N. Chrysomya bezziana infestation in a neglected squamous cell carcinoma on the face. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:81–2. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.45234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lefkowits C. Cutaneous myiasis: Maggot infestation of a malignant wound. Inst Enhance Palliat Care. 2012;12:1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maheshwari VJ, Naidu SG. Oral myiasis caused by Chrysomya bezziana: A case report. People's J Sci Res. 2010;3:25–6. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pereira T, Tamgadge AP, Chande MS, Bhalerao S, Tamgadge S. Oral myiasis. Contemp Clin Dent. 2010;1:275–6. doi: 10.4103/0976-237X.76401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Agrawal B, Dhole A, Deora S. Oral myiasis: A case report. Int J Dent Case Rep. 2012;2:61–5. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kumar JS. Oral myiasis: A case report. Pac J Med Sci. 2012;10:47–50. [Google Scholar]