Abstract

Adult obesity and overweight is affecting every region of the world and is described as one of today's most significant and neglected public health problems. The problem has taken the shape of an epidemic not only because the prevalence of obesity has witnessed a dramatic progress in a short period of time, but also because obesity has paved the way for increased risks for morbidity and mortality associated with it. It has been predicted that about half of the adult men and more than a quarter of adult women would be obese by 2030 in the UK and this figure could rise up to 50% in 2050 for whole of the adult UK population. Although a modest 5–10% weight loss maintained in the long term can significantly decrease health risk, few people engage in weight loss activities. Against this background, this review paper aims to investigate the reasons helping and/or hindering adults in the UK maintain weight loss in the long term; using online and organizational data sources and thematically analyzing the data. Self-body perception, enhanced self-confidence, social support, self-motivation, incentives and rewards, increased physical activity levels and healthy eating habits facilitated people in maintaining weight loss in the long term and overall quality of life. Extreme weather conditions, natural phenomena such as accidents, injuries and ill-health, work commitments, inability for time management and to resist the temptation for food constrained the successful long-term weight loss maintenance.

Keywords: Barriers and facilitators and weight maintenance, weight control, weight loss, weight maintenance, weight management

INTRODUCTION

Obesity is a complex, multifaceted condition characterized by excess or abnormal deposition of body fat that may jeopardize an individual's health.[1,2] It is caused by the interplay of many complex biological, psychological, socio-cultural, environmental and economic factors.[3] Almost all developed and developing countries in the world are afflicted by obesity epidemic, its prevalence has grown up from 312 million in 2004 to more than 1.4 billion obese adults in 2008.[4,5,6] Although not identical, terms obesity and overweight are often substituted for one another in practice and the figures for both of them are often combined; adding to the confusion and discrepancy in true estimates.[7,8]

Obesity affects all ages and both genders; differences can be observed in the prevalence of obesity across and within continents, countries, and states. There are regional differences in the prevalence of obesity within Europe; number of overweight and obese individuals is increasing in England when compared with other European countries.[9,10] Estimates from a health survey in England shows that a quarter of adult men and women were obese in 2004. It has been predicted that about half of the adult men and more than a quarter of adult women would be obese by 2030 in UK and this figure could rise up to 50% in 2050 for whole of the adult UK population.[11,12]

Excess body weight is associated with poor health and a range of noncommunicable diseases: Type 2 diabetes,[13,14] hypertension,[13,15] cardiovascular diseases,[13,16] stroke,[17] osteoarthritis,[18,19] gall stones,[20] benign prostatic hyperplasia,[21] obstructive sleep apnea[22,23] and some cancers like adenocarcinoma of esophagus and gastric cardia; endometrial, breast, and colon[6,13,24,25,26] leading to a massive impact on public health and related health economics. A fair estimate of this massive burden can be estimated by the fact that National Health Service and special health boards had planned to spent an amount of ≤ m 7,846.0–8,623.0 on health alone between a period of 2008–2011.[27]

Preventing obesity is a complex process and a key public health challenge. There are a number of interventions and strategies to tackle overweight and obesity throughout the world, depending on country, region and target population.[28] In the UK, number of initiatives such as saving lives: Our healthier nation, choosing health: Making healthier lives easier, the Scottish government's healthy eating, active living: An action plan to improve diet, increase physical activity and tackle obesity, the keep well initiative etc., have been formulated in light of the evidence-based causes of obesity in the UK and implemented to help people lose weight.[28,29,30,31,32,33,34] Although a modest weight loss maintained in the long term can significantly decrease health risk, few people engage in weight loss activities. Research studies have demonstrated the determinants of short-term weight loss maintenance. However, a few have attempted to explore the factors associated with long-term weight loss maintenance. Against this background, this review paper aims to investigate the reasons helping and/or hindering UK adults maintain weight loss in the long-term using online and organizational data sources and analyzing the data thematically.

METHODS

The scope of the literature search was determined by the probable applicability of research papers to the specific context of long-term weight loss maintenance. Compared to short term success, minimal literature is available on the factors associated with long-term weight loss maintenance. Therefore, a visionary search strategy was needed to identify relevant studies over diverse fields, including those neither published in peer-reviewed journals nor addressed in online databases to gain access to the relevant literature, to maximize support and gain evidence for the study.

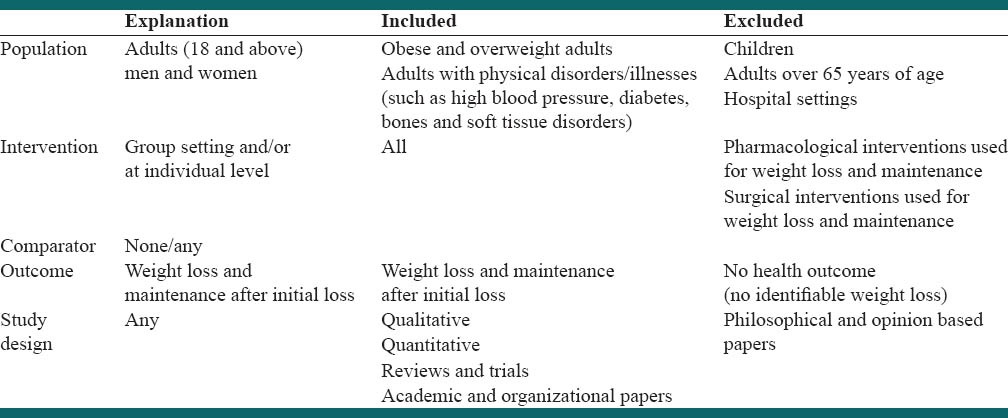

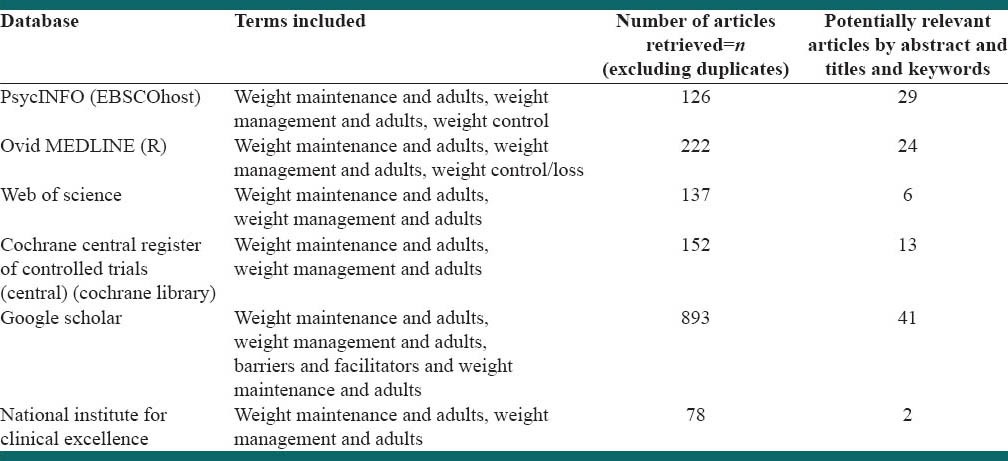

The PICO framework[35,36] was used to design inclusion and exclusion criteria for the literature review [Table 1]. Philosophy and opinion-based papers were not included in the review. A literature search was carried out using a number of online databases and search engines, academic and organizational papers on the topic of obesity and weight loss maintenance up to February 2014. Searches were restricted to dates (1991–2014; this period was chosen as the obesity prevalence is considered to be more conspicuous during past 20 years), language (English) and document type. To balance specificity and sensitivity of the search terms and fields, iterative refinements were carried out. The initial strategy was to include the term obes* and adults that generated a range of articles too wide to go further with, results were mainly focusing on short term weight loss. Filters were applied for humans and years of publication that narrowed down the search. Relevant articles were sought by using the term weight maintenance and adults. Further search was carried out using the terms (barriers) and (facilitators) and (weight maintenance), directly focusing on the research question [Table 2]. Weight loss maintenance programs in group settings as well as maintenance at individual level were included in literature search, permitting investigation of the relative influence of barriers and facilitators on weight loss maintenance with and without on-going peer support.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Table 2.

Literature search strategy

To discover grey literature (documents published by organizations, rather than academic journal articles or books), Google Scholar was used to sought organizational websites related to health and obesity. Citation searches and author searches were carried out on a few included articles as a final check against missing key reports.

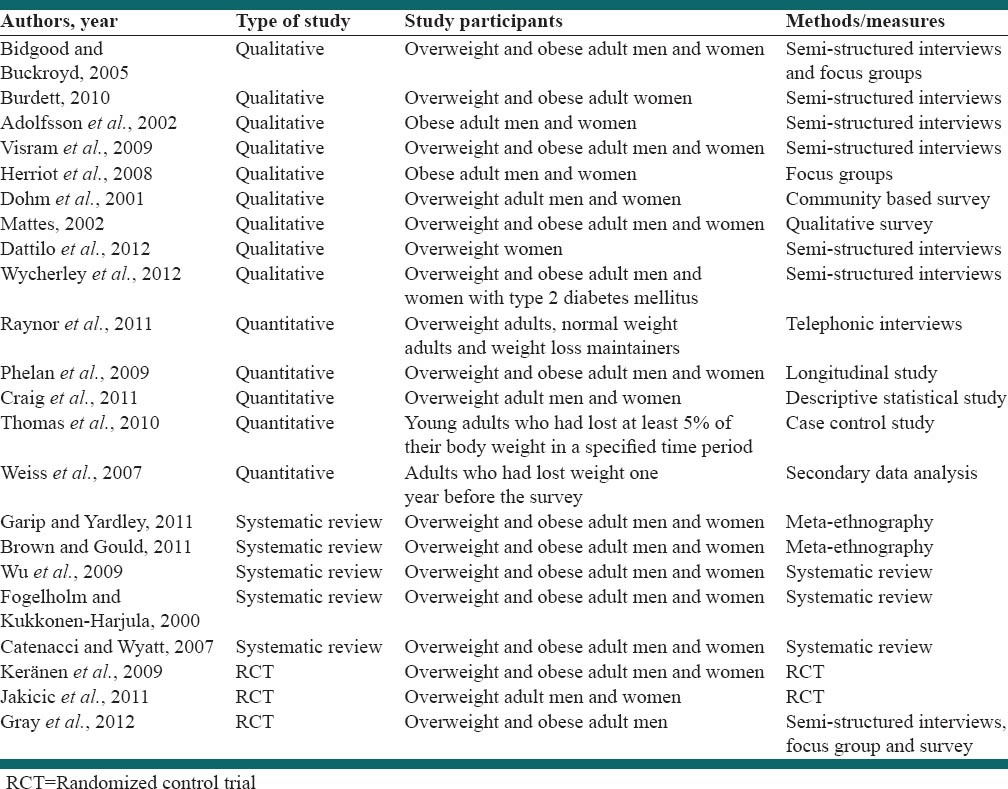

Relevant articles to be included in this section were selected in three different stages on the basis of inclusion and exclusion criteria [Table 1]. Preliminary scrutiny of the titles sieved out articles on the wrong topic, articles that seemed relevant were saved. Articles relevant by abstracts were considered in the next stage. Among these, articles which did not meet the inclusion and exclusion criteria, not found by abstract, not available free of cost, or the wrong article type were disqualified. A search with Google Scholar at a later stage revealed a number of items not found through other search engines, but some of these were difficult to find or not easily or freely available. Full texts of the remaining potentially relevant articles were obtained at the final stage of selection. At the end, all full-text articles were read, and those considered to have met the proposed criteria were included in this review. Twenty-two articles of relevance were found-nine qualitative studies,[28,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44] five quantitative studies,[45,46,47,48,49] five reviews[50,51,52,53,54] and three randomized control trials[55,56,57] [Table 3]. These studies included a mix of peer-reviewed papers published in academic journals and reports and were critically appraised, using Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) tool to avoid the risk of poorly found research evidence on these studies. The studies in which the study aims, study design and methodology were clearly defined, analysis was carried out appropriately, results were reported and presented well were given ratings ranging from poor to good against the CASP tool. The studies who were rated fair and good were included in the review.

Table 3.

Articles included in the review

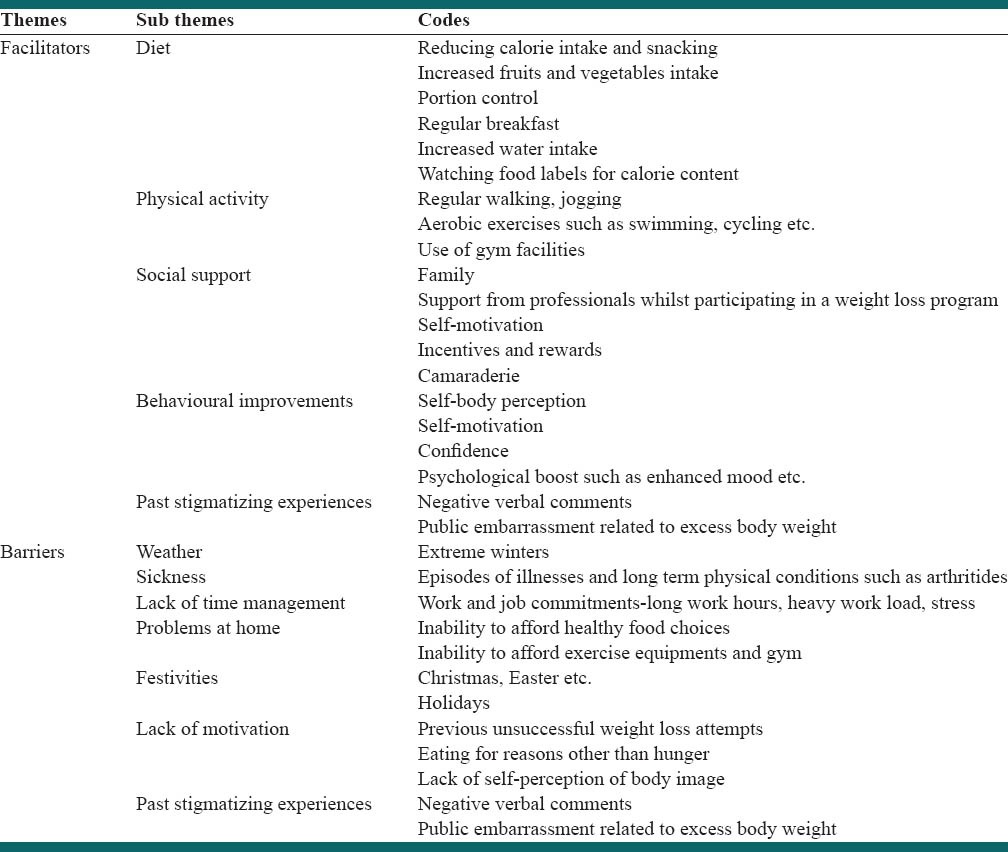

The review generated common themes for the study. The themes were described as facilitators of and barriers to long-term weight loss maintenance. The themes were then segregated into several sub themes, and codes common to the studies included in the review [Table 4]. Initially, the codes were tabulated in an unorganized fashion, and an apparent count was made of how many times each code was repeated (borrowing from content analysis). The next stage involved combining or bringing together similar ideas, taking apart the different ones and finally removing the duplicates to give a handy number of distinct themes and subcategories which were easy to manage and dealt with at a later stage. The themes and subcategories obtained were then cross-examined in light of the research questions; themes that seemed irrelevant to the study questions were dumped.

Table 4.

Themes, sub themes and codes

RESULTS

DISCUSSION

Facilitators

Self-body perception, self-motivation, behavioral improvements and past stigmatizing experiences helped people lose weight and maintaining weight loss in the long term.[28,37,40] Support from professionals while participating in a weight loss program, friends and family emerged as potential facilitators of weight loss in the long-term.[38,39] In some cases, sharing common interests and characteristics (age, similar physical conditions etc.) during weight loss program participation provided common platform to discuss potential issues, psychological boost and self-confidence which helped them in long-term weight loss maintenance.[57] This gives an insight into a possible relation between camaraderie and long-term weight loss maintenance, which needs to be explored further. However, these were small qualitative/quantitative studies wherein transferability cannot be claimed, however the same themes were apparent from different studies and thus increased their validity.

Literature demonstrates that adherence to low energy density diet, greater intake of fruits, vegetables and whole grains and decreased sugar consumption helped people with weight loss maintenance in the long term.[45,46] In addition, portion control, taking regular breakfast, increased daily water intake, studying food labels for calorie content while shopping for grocery facilitated long-term weight loss maintenance.[57]

Successful long-term weight loss maintenance was related to increased physical activity as well. Regular walking, jogging, aerobic exercises such as swimming, cycling, etc., had a noticeable impact on weight loss maintenance.[46,49] Appropriate and affordable exercise facilities in the neighborhood, getting incentives, and small rewards such as the provision of fee concession; free leisure cards etc., by gym authorities further facilitated long-term weight loss maintenance.[43] Not surprisingly, greater improvements were seen in those engaged both in physical activity and healthy eating.[56]

Barriers

Internal conflicts and psychological factors such as lack of willpower, lack of self-sabotage, self-perception of body image, past stigmatizing experiences related to excess body weight emerged as barriers to weight loss maintenance in the long term.[28,40,50] Interestingly, past stigmatizing experiences such as negative verbal comments and public embarrassment related to excess body weight were emerged as both facilitator and barrier to long-term weight loss maintenance. While these experiences motivated some people lose and maintain weight in the long term, they constrained others in following healthy eating habits and exercise regimes.[28,40]

Emotional factors (e.g., feeling unable to manage weight), work commitments, family-related issues such as problems at home, occasions/festivals (e.g. Christmas), inability to afford healthy food choices, exercise equipments and gym, incapacity for time management due to work and job commitments, restricted people follow the changed dietary patterns and exercise schedules and thus maintaining weight loss in the long-term.[48,53] Psychological factors, lifestyle, coping responses and cognitive attributions were other barriers to long-term weight loss maintenance.[40,41] These factors included inability to resist the temptation for junk food, huge portion size, eating for reasons other than hunger, depression, previous unsuccessful weight loss attempts, etc. These factors were primarily attributed to lack of self-motivation, lack of coping responses, internal conflicts and self-control.[28,37,44]

Research showed that those adults who were sedentary or not meeting public health recommendations for physical activity had a higher probability of weight regain than those who were meeting these guidelines.[46,49] This aspect of physical inactivity resulted primarily from a lack of willpower and motivation (largely self-motivation). In addition, environmental factors such as bad weather conditions specially extreme winters; and poor health, episodes of sickness and associated physical conditions such as arthritides further imposed restrictions on adherence to exercising.[47,50] Interestingly, a dose-response relationship was explored between physical activity and weight loss maintenance, suggesting a likely causal relationship between the two variables and thus increasing its credibility.[53,54]

CONCLUSIONS

The findings of the paper are widely dispersed and plentiful, providing an opportunity for literature to emerge demonstrating the relationship between long-term weight loss maintenance and its determinants. Self-body perception, self-motivation and stigmatizing experiences facilitate weight loss maintenance in the long term whereas weather, work commitments, internal conflicts and family related issues constraint the process in the long term. Apart from the traditional ways of cutting calories, adopting practices such as portion control, watching food labels, taking regular breakfast and increased water intake can help maintaining weight loss in the long term successfully. Self-motivation, motivation by family and friends, enhanced self-esteem, together with physical activity and healthy diet facilitate long-term weight loss maintenance and thus improve the overall quality of life. Additionally, the importance of camaraderie during weight loss program participation and maintaining it after program completion appeared as a valuable asset in this regard. However, scanty literature is available which talks about these concepts; the evidence could be further improved by carrying out longitudinal studies specially focusing on this theory. Moreover, the majority of studies have addressed the factors associated with short term weight loss maintenance which demonstrates the need to focus on the determinants of long-term weight loss maintenance. In order to provide high-quality evidence in the subject area; there is a need to carry out randomized control trials establishing causality between long-term weight loss maintenance and its determinants. Rigorous scientific enquiry is needed from future studies to address gap in the knowledge related to barriers and facilitators associated with obesity and long-term weight loss maintenance in adults.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lyznicki JM, Young DC, Riggs JA, Davis RM Council on Scientific Affairs, American Medical Association. Obesity: Assessment and management in primary care. Am Fam Physician. 2001;63:2185–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Samoa Report. Workshop on Obesity Prevention and Control Strategies in the Pacific Isles, Apia, Samoa. 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gortmaker SL, Swinburn BA, Levy D, Carter R, Mabry PL, Finegood DT, et al. Changing the future of obesity: Science, policy, and action. Lancet. 2011;378:838–47. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60815-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Finucane MM, Stevens GA, Cowan MJ, Danaei G, Lin JK, Paciorek CJ, et al. National, regional, and global trends in body-mass index since 1980: Systematic analysis of health examination surveys and epidemiological studies with 960 country-years and 9·1 million participants. Lancet. 2011;377:557–67. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62037-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.James PT, Rigby N, Leach R International Obesity Task Force. The obesity epidemic, metabolic syndrome and future prevention strategies. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2004;11:3–8. doi: 10.1097/01.hjr.0000114707.27531.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Geneva: WHO; [Last accessed on 2013 Sep 22]. WHO. obesity and Overweight, Fact Sheet no. 311. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en . [Google Scholar]

- 7.Field AE, Joaquin B, Colditz GA. Handbook of Obesity Treatment. London: The Guilford Press; 2004. Epidemiologic and health consequences of obesity. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hacking I. Cambridge University; 19-20 Sep; 2007. Fat Across the Disciplines, Conference at Newnham College. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Livingstone MB. Childhood obesity in Europe: A growing concern. Public Health Nutr. 2001;4:109–16. doi: 10.1079/phn2000106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scarborough P, Alleneder S. National Health and Service Information Centre for Health and Social Care. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Health and Service Information Centre for Health and Social Care, Statistics on Obesity, Physical Activity and Diet. 2009. [Last accessed on 2013 Sep 22]. Available from: http://www.ic.nhs.uk/webfiles/publications .

- 12.McPherson K, Marsh T, Brown M. Modelling future trends in obesity and impacts on health. Foresight tackling obesities: Future choices. [Last accessed on 2013 Oct 02]. Available from: http://www.foresight.gov.uk .

- 13.Kopelman P. Health risks associated with overweight and obesity. Obes Rev. 2007;8(Suppl 1):13–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2007.00311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boitard C. Insulin secretion in type 2 diabetes: Clinical aspects. Diabetes Metab. 2002;28:4S33–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kearney PM, Whelton M, Reynolds K, Muntner P, Whelton PK, He J. Global burden of hypertension: Analysis of worldwide data. 2005;365:217–23. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17741-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eckel RH, Barouch WW, Ershow AG. Report of the national heart, lung, and blood institute-national institute of diabetes and digestive and kidney diseases working group on the pathophysiology of obesity-associated cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2002;105:2923–8. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000017823.53114.4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stampfer MJ, Maclure KM, Colditz GA, Manson JE, Willett WC. Risk of symptomatic gallstones in women with severe obesity. Am J Clin Nutr. 1992;55:652–8. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/55.3.652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cooper C, Inskip H, Croft P, Campbell L, Smith G, McLaren M, et al. Individual risk factors for hip osteoarthritis: Obesity, hip injury, and physical activity. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;147:516–22. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cicuttini FM, Baker JR, Spector TD. The association of obesity with osteoarthritis of the hand and knee in women: A twin study. J Rheumatol. 1996;23:1221–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Must A, Spadano J, Coakley EH, Field AE, Colditz G, Dietz WH. The disease burden associated with overweight and obesity. JAMA. 1999;282:1523–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.16.1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Giovannucci E, Rimm EB, Chute CG, Kawachi I, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, et al. Obesity and benign prostatic hyperplasia. Am J Epidemiol. 1994;140:989–1002. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grunstein RR, Stenlöf K, Hedner J, Sjöström L. Impact of obstructive sleep apnea and sleepiness on metabolic and cardiovascular risk factors in the Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) Study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1993a;19:410–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grunstein RR, Stenlof K, Hedner J, Sjostrom L. Impact of obstructive sleep apnoea and sleepiness on cardiovascular and metabolic risk factors in the Swedish obese subjects (SOS) study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1993;; 19:410–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dobson R. Obesity is a risk factor for 70,000 new cancers a year in Europe. Br Med J. 2009;339:3171. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lagergren J, Bergström R, Nyrén O. Association between body mass and adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and gastric cardia. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130:883–90. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-11-199906010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scottish Public Health Observatory. 2007. [Last accessed on 2013 Oct 16]. Available from: http://www.scotpho.org.uk/home/Publications/scotphoreports/pub_obesityinscotland.asp .

- 27.Edinburgh: Scottish Government; 2007. [Last accessed on 2013 Oct 16]. Scottish Budget Spending Review 2007. Available from: http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Publications/2007/11/13092240/0, http://www.scotlandperforms.com . [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burdett TM. University of Southampton; 2010. Being connected: An exploration of women's weight loss experience and the implications for health education [dissertation] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abbotts J. Institute of Health and Well Being: Glasgow University; 2011. Out of the box: Impact of lateral thinking on health and well being [dissertation] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vol. 1. Scotland: Scottish Health Survey; 2009. [Last accessed on 2013 Oct 24]. Scottish Government; pp. 2042–1613. Main Report. Available from: http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Publications/2010/09/23154223/0 . [Google Scholar]

- 31.Preventing Overweight and Obesity in Scotland: A Route Map towards Healthy Weight. Scottish Executive. 2010. [Last accessed on 2013 Oct 16]. Available from: http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Publications/2010/02/17140721/0 .

- 32.Edinburgh: SIGN; 2010. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. Management of obesity. A national clinical guideline. SIGN guideline no. 115. [Google Scholar]

- 33.National Health and Service Information Centre for Health and Social Care, Statistics on Obesity, Physical Activity and Diet. 2011. [Last accessed on 2013 Oct 16]. Available from: http://www.ic.nhs.uk/webfiles/publications .

- 34.London: The stationery office; 2007. [Last accessed on 2013 Oct 16]. United Kingdom government office for science. Foresight tackling obesities: Future choices. Available from: http://www.foresight.gov.uk . [Google Scholar]

- 35.Counsell C. Formulating questions and locating primary studies for inclusion in systematic reviews. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:380–7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-5-199709010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Richardson WS, Wilson MC, Nishikawa J, Hayward RS. The well-built clinical question: A key to evidence-based decisions. ACP J Club. 1995;123:A12–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bidgood J, Buckroyd J. An exploration of obese adults experiences of attempting to lose weight and to maintain a reduced weight. Couns Psychother Res. 2005;5:221–9. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Adolfsson B, Carlson A, Undén AL, Rössner S. Treating obesity: A qualitative evaluation of a lifestyle intervention for weight reduction. Health Educ J. 2002;61:244. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Visram S, Crosland A, Cording H. Triggers for weight gain and loss among participants in a primary care-based intervention. Br J Community Nurs. 2009;14:495–501. doi: 10.12968/bjcn.2009.14.11.45008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Herriot AM, Thomas DE, Hart KH, Warren J, Truby H. A qualitative investigation of individuals’ experiences and expectations before and after completing a trial of commercial weight loss programmes. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2008;21:72–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-277X.2007.00837.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dohm FA, Beattie JA, Aibel C, Striegel-Moore RH. Factors differentiating women and men who successfully maintain weight loss from women and men who do not. J Clin Psychol. 2001;57:105–17. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(200101)57:1<105::aid-jclp11>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mattes RD. Feeding behaviors and weight loss outcomes over 64 months. Eat Behav. 2002;3:191–204. doi: 10.1016/s1471-0153(01)00059-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dattilo AM, Birch L, Krebs NF, Lake A, Taveras EM, Saavedra JM. Need for early interventions in the prevention of pediatric overweight: A review and upcoming directions. J Obes 2012. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/123023. 123023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wycherley TP, Mohr P, Noakes M, Clifton PM, Brinkworth GD. Self-reported facilitators of, and impediments to maintenance of healthy lifestyle behaviours following a supervised research-based lifestyle intervention programme in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2012;29:632–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2011.03451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Raynor HA, Van Walleghen EL, Bachman JL, Looney SM, Phelan S, Wing RR. Dietary energy density and successful weight loss maintenance. Eat Behav. 2011;12:119–25. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2011.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Phelan S, Wing RR, Loria CM, Kim Y, Lewis CE. Prevalence and predictors of weight-loss maintenance in a biracial cohort: Results from the coronary artery risk development in young adults study. Am J Prev Med. 2010;39:546–54. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Melville CA, Boyle S, Miller S, Macmillan S, Penpraze V, Pert C, et al. An open study of the effectiveness of a multi-component weight-loss intervention for adults with intellectual disabilities and obesity. Br J Nutr. 2011;105:1553–62. doi: 10.1017/S0007114510005362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thomas D, Vydelingum V, Lawrence J. E-mail contact as an effective strategy in the maintenance of weight loss in adults. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2011;24:32–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-277X.2010.01123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weiss EC, Galuska DA, Kettel Khan L, Gillespie C, Serdula MK. Weight regain in U.S. adults who experienced substantial weight loss, 1999-2002. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33:34–40. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Garip G, Yardley L. A synthesis of qualitative research on overweight and obese people's views and experiences of weight management. 2011. [Last accessed on 2013 Feb 24]. Available from: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j. 1758-8111.2011.00021.x/full . [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Brown I, Gould J. Decisions about weight management: A synthesis of qualitative studies of obesity. Clinical Obesity. 2011;1:99–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1758-8111.2011.00020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wu T, Gao X, Chen M, van Dam RM. Long-term effectiveness of diet-plus-exercise interventions vs. diet-only interventions for weight loss: A meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2009;10:313–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2008.00547.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fogelholm M, Kukkonen-Harjula K. Does physical activity prevent weight gain – a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2000;1:95–111. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-789x.2000.00016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Catenacci VA, Wyatt HR. The role of physical activity in producing and maintaining weight loss. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab. 2007;3:518–29. doi: 10.1038/ncpendmet0554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Keränen AM, Savolainen MJ, Reponen AH, Kujari ML, Lindeman SM, Bloigu RS, et al. The effect of eating behavior on weight loss and maintenance during a lifestyle intervention. Prev Med. 2009;49:32–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jakicic JM, Otto AD, Lang W, Semler L, Winters C, Polzien K, et al. The effect of physical activity on 18-month weight change in overweight adults. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2011;19:100–9. doi: 10.1038/oby.2010.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gray CM, Hunt K, Mutrie N, Anderson AS, Treweek S, Leishman J, et al. Can professional soccer clubs help male fans lose weight and become more physically active? Preliminary evidence from the Scottish Premier League. J Sci Medicine in Sport. 2012;15(6 Suppl):367. [Google Scholar]