Abstract

Background:

With the change in population policy from birth control toward encouraging birth and population growth in Iran, repeated cesarean deliveries as a main reason of cesarean section are associated with more potential adverse consequences. The aim of this research was to explore effective strategies to reduce cesarean delivery rates in Iran.

Methods:

A mixed methodological study was designed and implemented. First, using a qualitative approach, concepts and influencing factors of increased cesarean delivery were explored. Based on the findings of this phase of the study, a questionnaire including the proposed strategies to reduce cesarean delivery was developed. Then in a quantitative phase, the questionnaire was assessed by key informants from across the country and evaluated to obtain more effective strategies to reduce cesarean delivery. Ten participants in the qualitative study included policy makers from the Ministry of Health, obstetricians, midwives and anthropologists. In the next step, 141 participants from private and public hospitals, insurance experts, Academic Associations of Midwifery, and policy makers in Maternity Health Affairs of Ministry of Health were invited to assess and provide feedback on the strategies that work to reduce cesarean deliveries.

Results:

Qualitative data analysis showed four concept related to increased cesarean delivery rates including; “standardization”, “education”, “amending regulations”, and “performance supervision”. Effective strategies extracted from qualitative data were rated by participants then, using ACCEPT derived from A as attainability, C as costing, C as complication, E as effectiveness, P as popularity, and T as timing table 19 strategies were detected as priorities.

Conclusions:

Although developing effective strategies to reduce cesarean delivery rates is complex process because of the multi-factorial nature of increased cesarean deliveries, in this study we have achieved strategies that in the context of Iran could work.

Keywords: Cesarean delivery, Iran, mixed methods

INTRODUCTION

Birth control policies have been replaced by birth encouragement policies in Iran,[1] nowadays and increasing elective and repeat cesarean deliveries, known as the major cause of cesarean in the country associated with greater risks and consequences threaten safety of the community. Increased caesarean sections in most countries including Iran have dramatically skyrocketed and become a health problem for health managers. Caesarean sections as a rescue operation for the mother and the fetus can be associated with many complications and costs.[2] A cesarean rate of 35% was reported by the DHS study that took place in Iran, in 2000.[3] The rate in 2005, was 40.7%. More than half of the cesarean sections (52%) are done in Tehran, and 64% of these 52% are done in private hospitals.[4] The annual expected cesarean rate is estimated by World Health Organization is 10–15% in developing countries.[5] Although there are no accurate statistics on the amount of elective caesarean section in the country, almost everyone knows that the large portion of caesarean sections rates are elective surgeries in Iran.

Despite the expansion of cesarean section rates, there is no evidence that reveals improved outcomes for the mother or the baby, moreover, cesarean delivery has more potential adverse consequences than vaginal delivery.[6] Moreover, unnecessary cesarean delivery is unethical issue due to the various expenses that are imposed by the health system.[7,8]

A large portion of increased cesarean rates in Iran is related to health care providers’ concerns about legal issues that may occur for them in vaginal delivery in the labor room.[9] So to avoid being involved in legal issues it is easier for obstetricians and midwives to shift deliveries to surgery than vaginal delivery.[9] On the other hand, obstetricians are not interested in vaginal deliveries because of lack of time to spend conducting a normal birth, and also lack of enough competency and skills to handle complicated vaginal deliveries.[9] Financial issues and insurance payment are influencing but often is not mentioned clearly by obstetricians.[10]

Mothers’ concerns about labor pain as reported in many studies,[11,12] were strongly emphasized by the participants in this study. They said that due to increased rates of cesarean delivery in the country, many midwives and obstetricians have lost their professional competency, or they lack of standard physical spaces, have manpower shortages for care in labor, making it impossible to provide pain relief care for mothers.

A qualitative study in Iran showed that a cesarean delivery by maternal request is a multi-factorial issue. Fears of the unknown, intense pain in natural childbirth, adverse experiences of vaginal delivery, maternal concern about complications following vaginal delivery and improper communication of medical staff during vaginal delivery are the main reasons that encourage maternal request for cesarean deliveries.[13] Doctors often counsel patients on choosing the elective cesarean section as a type of delivery with safer neonatal complications in comparison with emergency cesarean, which often encourages mothers to select elective cesarean section. However, this choice does not reduce the incidence of maternal complications.[14] Complex relationships between parents, the community, health care providers, and cultural factors, socioeconomic are important factors that influence rise in cesarean rates in different countries. Sometimes it is done on the mother's request without a medical reason, and sometimes also offered by expert service provider.

The Maternal Health Office has been designed and has implemented many health promotion programs to reduce cesarean section for several years.[15] Some of these programs are include: Designing and operation of the mother-friendly hospitals, developing standard protocols to reduce the pain of natural childbirth methods, childbirth preparation classes for mothers, midwives, gynecologists and empowerment workshops for specialists and midwives. But because of the multifaceted nature of increased cesarean section rates, intersectoral activities must be done.

Although many studies have been done worldwide in order to understand the real causes of skyrocketing elective cesarean and interventions to reduce rate, an appropriate policy that could be used to reduce the amount of elective caesarean section is uncertain.[16] Now with the change in population policy and encouraging people to have more births, increased cesarean surgeries in Iran are associated with greater risks and inappropriate consequences.[17] The purpose of this study was to explore the challenges and strategies required to reduce current rates of cesarean section.

METHODS

Qualitative study

Approach

The present research was designed as a sequential exploratory mixed methods study. The intent of the two phase exploratory design is that the results of the first method (qualitative) can help develop the second method (quantitative). The design is useful when a researcher needs to develop and test an instrument or identify the important variables to study quantitatively, when the variables are unknown.[18] In this study, the researchers explored the effective strategies that could be implemented in the context of Iran to reduce cesarean delivery rates.

Sample

Participants were policy makers and health care providers, who were actively working in health services. Thus, in a qualitative study, 11 in-depth semi-structured interviews were conducted with obstetricians, midwives, sociologist, which worked in private or governmental sections. The participants were recruited by convenience sampling and then followed by purposive sampling that lasted for 3 months. The first participant was a colleague of one of the authors. She was an obstetrician that had much tendency to and high level of cesarean rates in her work. The majority of the participants were selected based on their experiences and fame in policy making, and/or work in the delivery room, or education of the students of midwifery or residents of obstetrics. They were invited by phone. The sampling was continued till saturation occurred. Data collection was carried out by the main researcher that had PhD degree in Reproductive Health.

Participants declared oral informed consent before the beginning of interviews and were asked before recording the interview.

Data collection

Purposeful sampling was used for 3 months from October 2012 to January 2013. Eleven interviews have been done ten participants. Also, reports and minutes of meeting related to reducing cesarean deliveries that were available in Maternity Health Affairs of Ministry of Health were used and analyzed. Participants declared oral informed consent before the beginning of interviews and were asked to tape the interviews, which were conducted by prior arrangement. The participants’ experiences and their perceptions regarding the causes of increased cesarean deliveries were collected during semi-structured in-depth interviews. Data collection was carried out by the main researcher, and audio taped. These records were then transcribed verbatim and analyzed consecutively.

On average, each interview lasted 45 min (30–65). Semi structured interview guidelines were used. Interview was begun with an open question about her/his opinion about cesarean delivery rates and related factors – “what do you think about the rates of cesarean delivery in Iran?” and then further questions about details of reasons of increased cesarean deliveries? “What's your choice for your own delivery or answer to a relative or friend if ask you about the better mode for delivery and why?” “How can we reduce cesarean delivery rates?” Whenever it was necessary, probe question was asked. Interviews continued until saturation.

Data analysis

Qualitative data analysis was conducted manually based on conventional content analysis guided by constant comparative analysis. Open and axial coding was applied to the data. Gathering and analyzing data continued until saturation was reached.

Validity

In this mixed methods study, validity of both the qualitative data and the questionnaire was assessed. To evaluate the rigor and enhance the trustworthiness of qualitative data, we drew on Lincoln and Guba's (2000) criteria, which included credibility, transferability, dependability, and conformability. Credibility, which refers to the confidence one can have in the findings, can be established by some strategies in qualitative research, including prolonged engagement, peer debriefing, and member checking. Member checking gave the participants the opportunity to accept or reject the conclusions extracted from data. Lincoln and Guba consider this process as the most important procedure for establishing credibility in the study.[19]

In this study, two randomly selected participants were given a full transcript of their coded interviews with a summary of the emergent themes to determine whether the codes and themes matched their point of view.[20] All participants confirmed the themes that were developed by the research team. Another method of establishing rigor is peer debriefing that provides an external check of bias that may form in data analysis process. Peer debriefing was accomplished by sharing the data and ongoing analysis with two senior experts in qualitative research. Both dependability and conformability were accomplished using an audit trail. In order to ensure data accuracy and consistent interpretations during the course of data analysis, the research team kept decision trails to document the decisions that were made over the course of the study. In order to assess the reliability of the data, independent coding was carried out by two authors and concordance was calculated to be highly acceptable. In order to ensure rigor, the entire research process was also supervised by experts in the qualitative study.

Quantitative study

Sample

Two groups of participants were recruited in the quantitative study, one including midwives and obstetricians and the other group was policy makers or other experts that had some experiences in similar projects, including anesthesiologists, pediatricians, PhD of Reproductive Health, PhD of community medicine, GP, PhD of Health Service Management, PhD of Health Education, Health Economics, and Sociologists.

The questionnaire was assessed by key informants from across the country and evaluated to obtain more effective strategies to reduce cesarean delivery. One hundred sixty questionnaires were E-mailed to participants. Overall 141 participants have answered to the questionnaire. Participants completed the questionnaire electronically and returned them back by E-mail. Approximately 90% of the questionnaires were completed and returned. Completing every questionnaire took 15 min.

Data collection

To develop a questionnaire for assessing participants’ viewpoints about strategies that could work to reduce cesarean delivery rates, items were extracted from qualitative data. Fifty one items as the important strategies to reduce cesarean on 7-point Likert scale, each from totally agree to totally disagree were included to the initial pool.

Data analysis

Data analysis was done by IBM Corp. Released 2010. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 19.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp. Demographic variables of the participants were education, type of service providing and the sector that they were working. Data analysis was designed in two stages: In the first stage the items that obtained scores of 6 or 7 by at least 70% of the participants were retained. In the second stage, the strategies that had enough scores were prioritized by researchers.

For decision making on found strategies, we used multiple-criteria decision making that is well-known decision-making process using methods and procedures of multiple conflicting criteria into the management planning process.

Multiple-criteria decision making has two basic approaches; multiple attribute decision making (MADM) and multiple objectives decision making. There are a number of methods in each of the mentioned approaches. The simple additive weighting (SAW), one of the oldest methods, is under the MADM approaches. In this study, we used the ACCEPT technique that is under SAW method for weighting our strategies. ACCEPT is an acronym is derived from: A as attainability, C as costing, C as complication, E as effectiveness, P as popularity, and T as timing. Each selected strategies was weighted based on these six criteria.[21]

Validity

Validity of the questionnaire is an index that reveals that to what extent the questionnaire really measures the purpose of research. A valid questionnaire is one that is enough, appropriate and logical to measure the variables we are following.[22] Then face, and content validity of the questionnaire were assessed by 10 experts. Opinions and comments from 10 specialists were obtained and applied to the revision of the questionnaire. To assess the reliability of the questionnaire, twenty persons completed the questionnaire and after 1-week they filled out them again. Then Cronbach's alpha was calculated.

Ethics

This study was a common project of WHO, Ministry of Health and Endocrine Research Center of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences and has been approved by both the Scientific Research Committee and the Ethics Committee of the Endocrine Research Center of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences (No. 219).

RESULTS

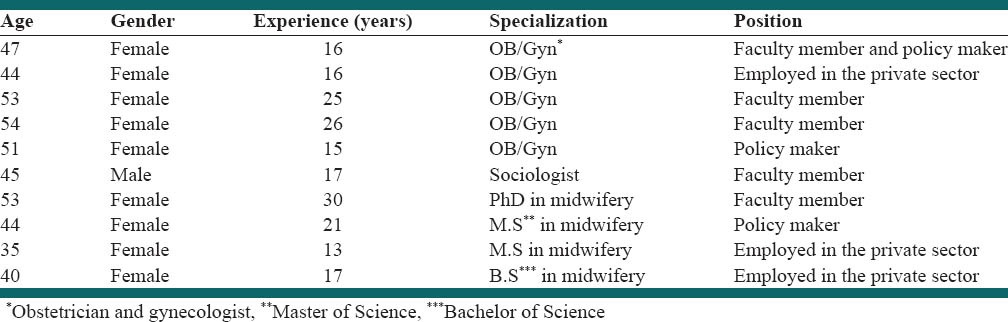

Findings are presented in three sections. Demographic characteristics of participants in the qualitative study have been shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of participants in the qualitative study

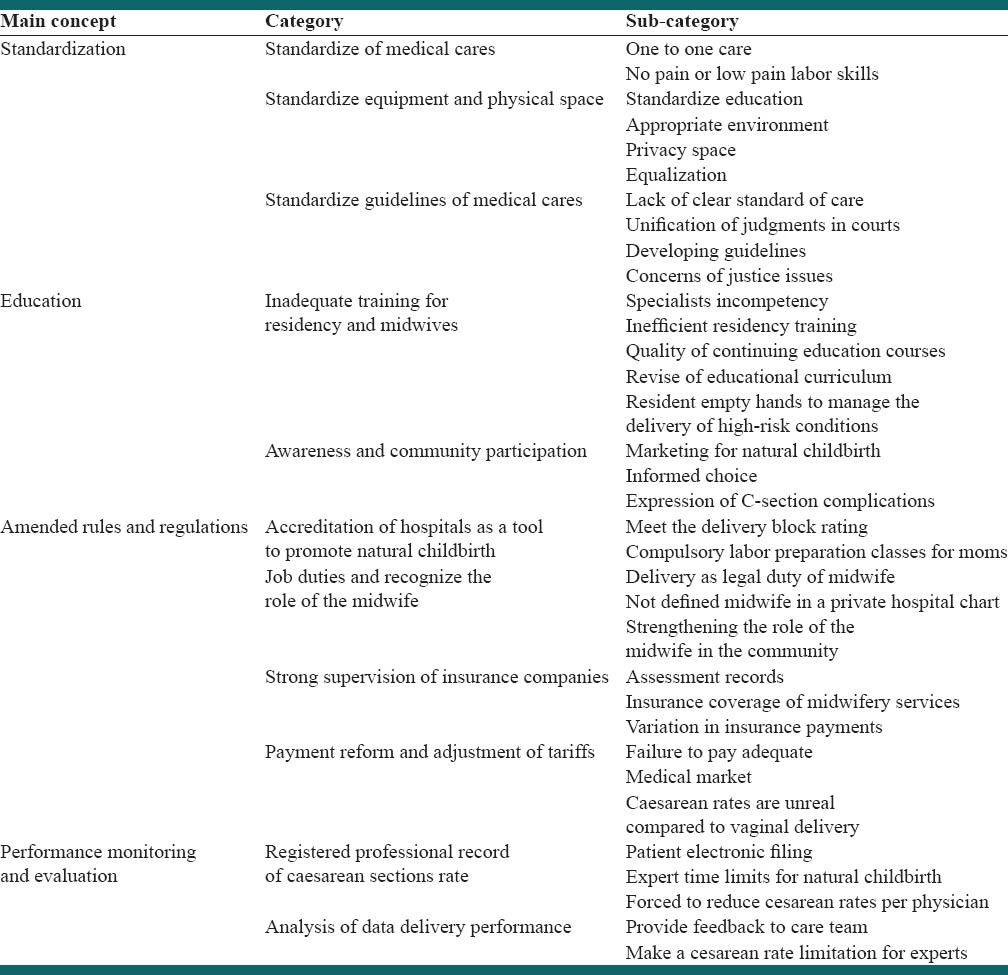

Qualitative data analysis showed four main concepts and strategies [Table 2] that may help to overcome the factors associated with increased cesarean section produced from qualitative data analysis.

Table 2.

Concepts, codes and strategies for reducing cesarean section rate

Qualitative study

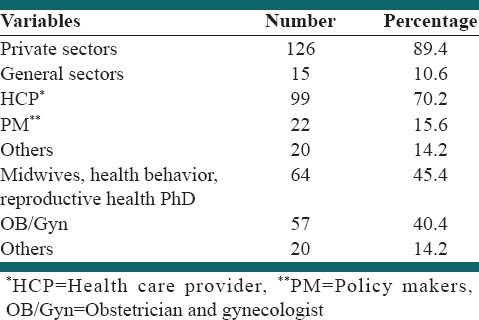

Demographic characteristics of the participants in the quantitative study have been shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Demographic characteristics of participants in the quantitative study

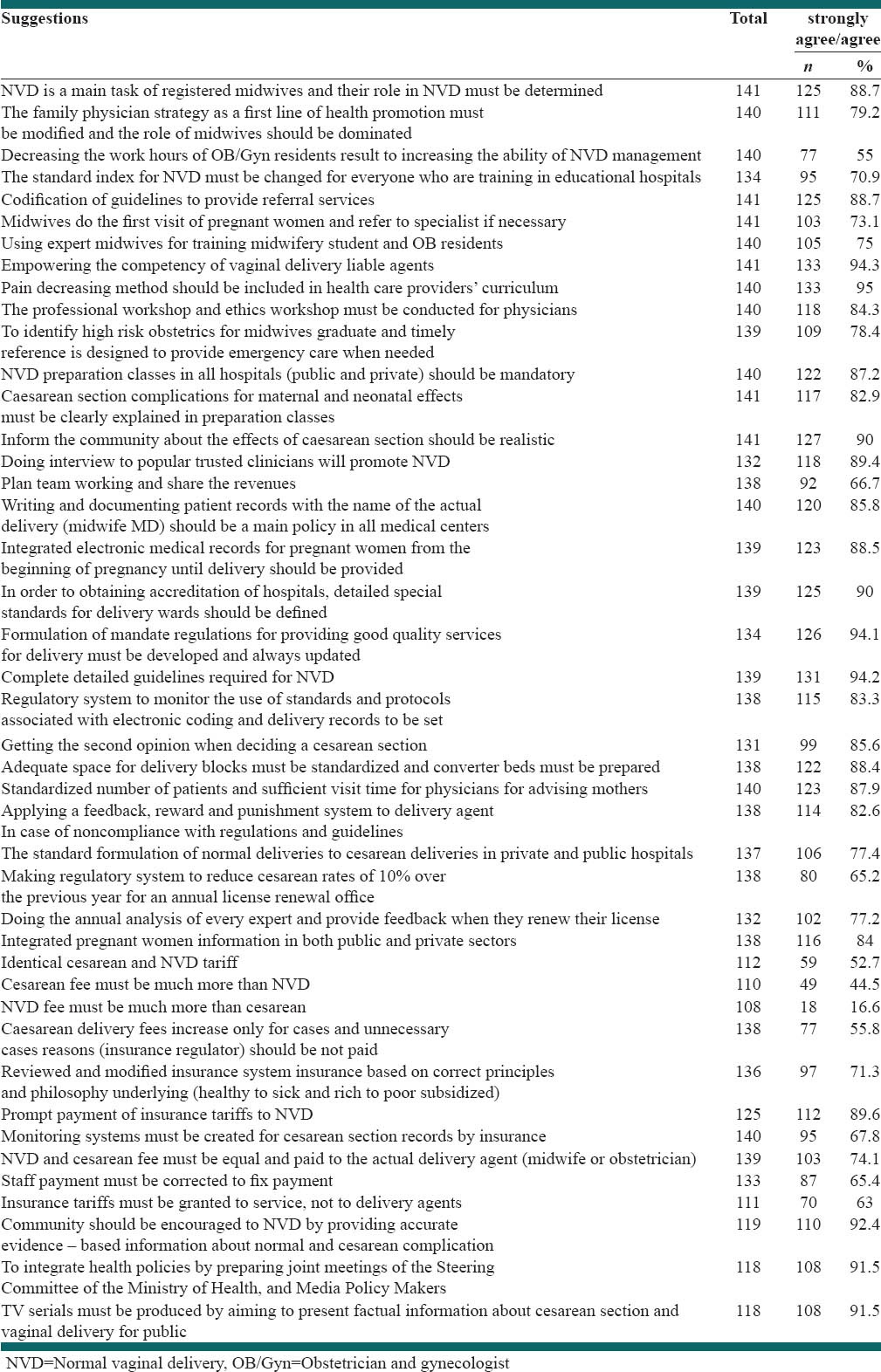

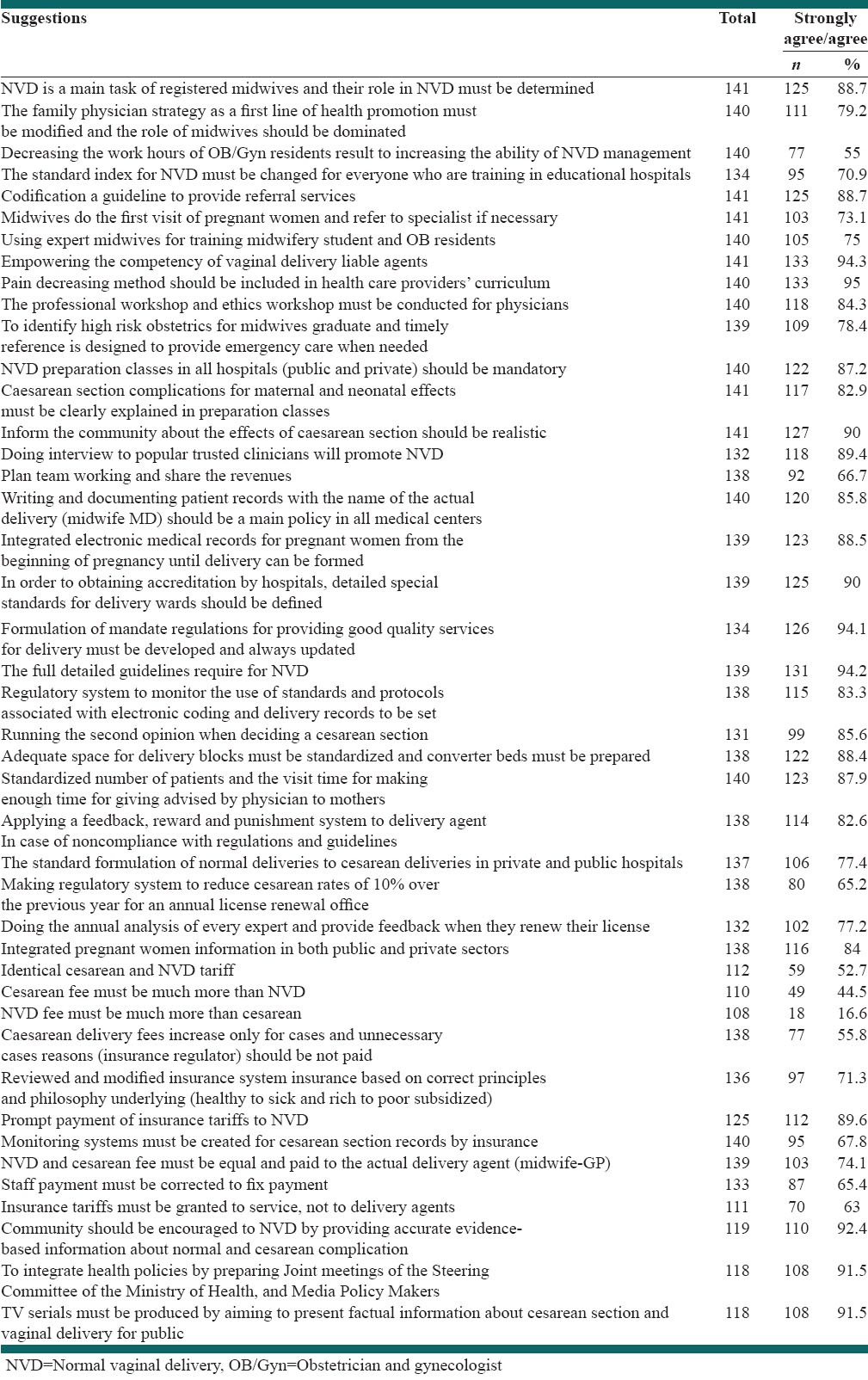

After assessment of face and content validity of the questionnaire, of 51 items, 43 were remained and 8 items were deleted. The reliability of the questionnaire was calculated by Cronbach's alpha value as 0.87. The final version of the questionnaire had 43 items in 7-point Likert type scale including strategies to decrease cesarean rates [Table 4].

Table 4.

Agreement percentages to suggestions based on participants answering (agree/strongly agrees) and most dominant answers that highlighted (cut off point ≥85%)

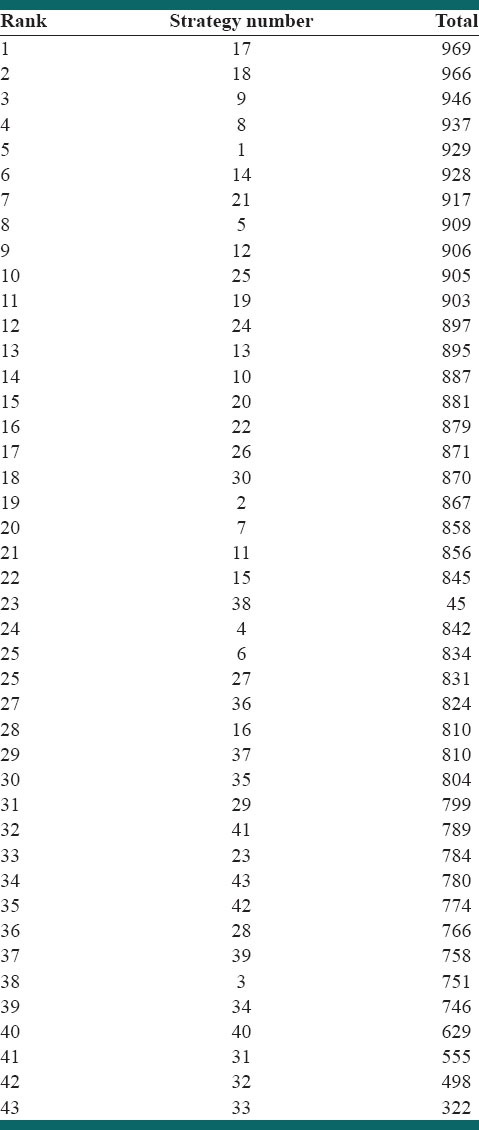

Total scores of suggestions were calculated [Table 5], and the 10 highest ranking strategies were listed. These 10 strategies include:

Table 5.

Ranked suggestions based on total number

Documenting patient records with the name of the actual delivery (midwife MD) should be the main policy in all medical centers (S17)

Integrated electronic medical records for pregnant women from the beginning of pregnancy until delivery should be formed (S18)

Pain reduction method should be included in health care providers’ curriculum (S9)

Empowering the competency of vaginal delivery liable agents (S8)

Normal vaginal delivery (NVD) is the main task of registered midwives, and their role in NVD must be determined (S1)

Informing the community about the effects of caesarean section should be realistic (S14)

Complete detailed guidelines required for NVD (S21)

Codification of guidelines to provide referral services (S5)

NVD preparation classes in all hospitals (public and private) should be mandatory (S12)

Standardized number of patients and sufficient visit time for mothers to be advised by a physician (S25).

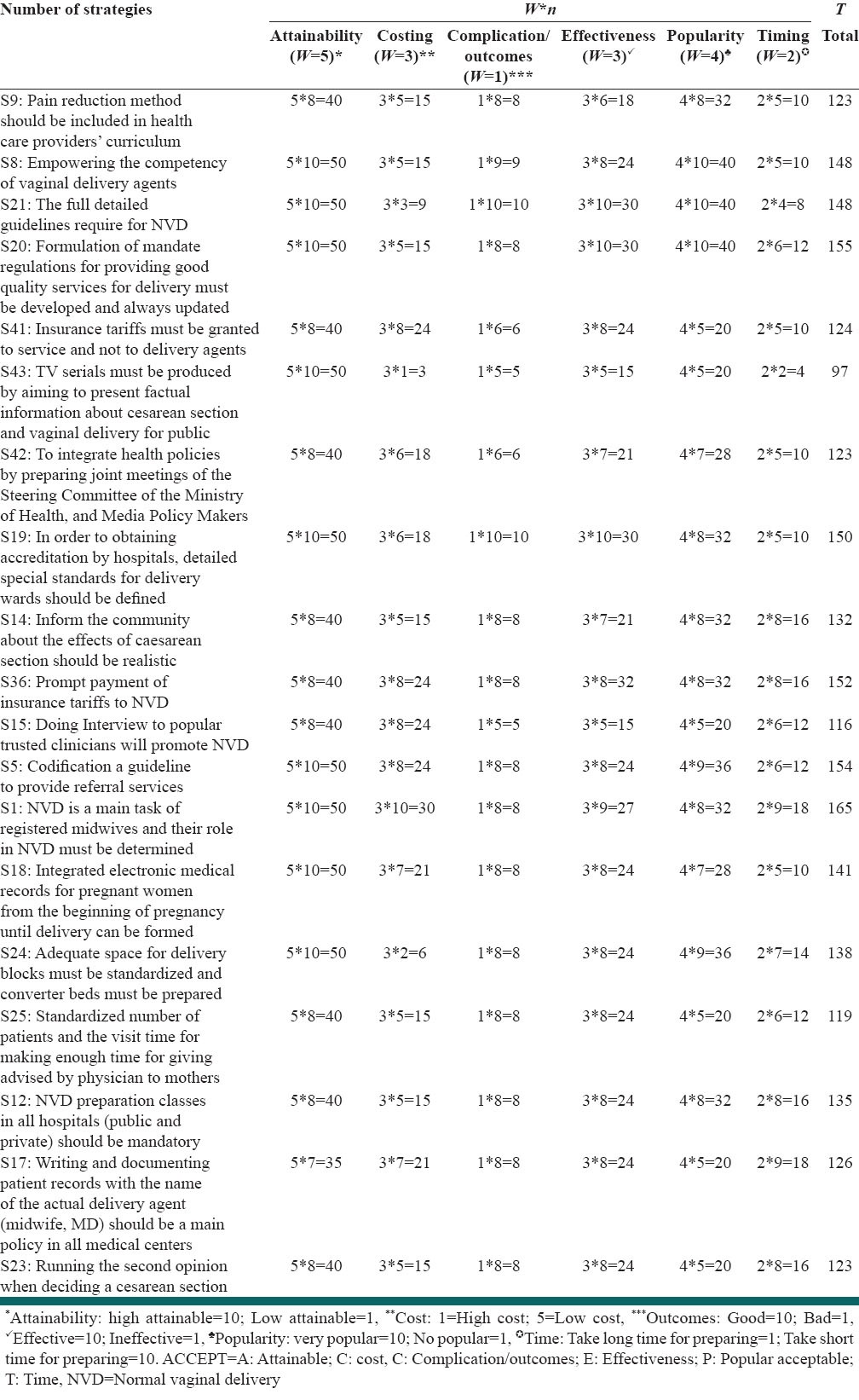

Then the highest level of agreement with each item was weighted [Table 6] using ACCEPT (A: Attainable, C: cost, C: Complication/outcomes, E: Effectiveness, P: Popular acceptable, T: Time), [Table 7]. Finally, 19 strategies were obtained by applying a 85% cut off point.

Table 6.

Strategies ranked based on ACCEPT analysis method

Table 7.

Agreement percentages to suggestions based on participants answering (agree/strongly agrees) and most dominant answers that highlighted (cut point ≥85%)

Ranked strategies after weighting from high to low level included:

NVD is the main task of registered midwives, and their role in NVD must be determined (S1)

Formulation of mandate regulations for providing good quality services for delivery must be developed and always updated (S20)

Codification of guidelines to provide referral services (S5)

Prompt payment of insurance tariffs to NVD (S36)

In order to obtaining accreditation by hospitals, detailed special standards for delivery wards should be defined (S19)

Empowering the competency of vaginal delivery at agents (obstetricians and midwives) (S8)

Detailed guidelines required for NVD (S21)

Integrated electronic medical records for pregnant women from the beginning of pregnancy until delivery should be created (S18)

Adequate space for delivery blocks must be standardized, and converter beds must be prepared (S 24)

NVD preparation classes in all hospitals (public and private) should be mandatory (S 12)

Informing the community about the effects of caesarean section should be realistic (S14)

Writing and documenting patient records with the name of the actual delivery (midwife MD) should be the main policy in all medical centers (S17)

Community should be encouraged to NVD by providing accurate evidence based information about normal and cesarean complications (S41)

Pain reduction methods should be included in health care providers’ curriculum (S9)

To integrate health policies by preparing Joint meetings of the Steering Committee of the Ministry of Health, and media policy makers (S42)

Getting a second opinion when deciding a cesarean section (S23)

Standardized number of patients and sufficient visit time for physicians advising mothers (S25)

Interviews by trusted clinicians to promote NVD (S15)

Producing TV serials/programs by aiming to present factual information about cesarean section and vaginal delivery for community (S43).

DISCUSSION

The present study is the first research using mixed methods approach aimed of exploring reasons of increased cesarean delivery and strategies that may work to decrease cesarean delivery rates. The results of the qualitative phase of this study indicate that it is a multidimensional issue and reducing the cesarean delivery rates is a difficult and complex project, and cannot be easily implemented by practical solutions in the short term. Nonetheless, nineteen strategies have been suggested by participants as the proper strategies to reduce cesarean deliveries. Overall, the suggested strategies can be divided into three categories.

First, strategies suggested by the participants mostly were focused on the role of qualified and skilled midwives and obstetricians to manage and handle a safe vaginal delivery. Second, informing the community about the outcomes of caesarean section should be realistic to able mothers to make a proper decision for their delivery. Third, strategies that promote standards and developing regulation to provide good quality care.

Potential risks of cesarean delivery on maternal request as a major reason of elective cesarean delivery rates include a longer maternal hospital stay, an increased risk of respiratory problems for the baby,[23] long term complications for baby,[24] and greater complications in subsequent pregnancies,[6] including uterine rupture and placental implantation problems.[25,7] Elective cesarean delivery on maternal request is not recommended for women desiring several children, given that the risks of placenta previa, placenta accreta, and the need for gravid hysterectomy increase with each cesarean delivery.[26]

Increasing trend of cesarean in the past 30 years has shown a 6-fold increase in Iran.[17] As indicated in other studies, widespread behavior changes at different levels are necessary in order to control growing cesarean section rates in the community.

Based on the participants’ opinion, one of the most important strategies to reduce cesarean section was empowering midwives to obtain good qualification to do safe vaginal delivery because NVD is a real task of them. Obstetrician's willingness in reducing cesarean delivery rates is critical, but many of the participants believed that obstetricians are not interested to do vaginal deliveries because of lack of time enough to spend conducting a normal birth, and more important reason was lack of competency and skills to handle complicated vaginal deliveries. Also, obstetricians in this study called cesarean as a safe mode of delivery for mother and child because of having more control in the situation. This has been confirmed in another study.[27] On the other hand, governmental policy making for rising populations in Iran, create concerns about women that tend to have several children. Hence, negative attitudes of health care providers especially obstetricians must be modified. In line with another research this is an important matter, and there must be conditions that persuade obstetricians to prefer vaginal delivery, otherwise we cannot expect to reduce cesarean deliveries.[28]

Lack of sufficiently skilled midwives to conduct vaginal deliveries was issue expressed as a reason by participants that leads them to have a cesarean delivery to avoid being involved in legal issues, as other study revealed.[9] Therefore in the opinion of the participants, developing programs to train expert midwives is essential must be considered. According to the job description approved by the Ministry of Health and Medical Education, midwives are trained for natural childbirth, not preparing mothers to go to the operating room. About half of the deliveries in Iran are related to cesarean deliveries, even in some private hospitals the rate is around 90%. Many of the midwives are hence unemployed. Studies show that raising the competencies of the professionals and using well experienced health care providers were effective in reducing cesarean deliveries.[29] Therefore, it seriously suggested that normal deliveries must be done by midwives, because it is their responsibility.

Certainly some of the unnecessary cesarean sections are done because of medical uncertainty and hesitation feasibility of natural childbirth. Using experts in such situations, cesarean deliveries rates can be reduced without causing adverse consequences. Using the second opinion approach in complicated situations of childbirth was shown to be effective in reducing cesarean deliveries in Althabe et al. study.[29] This is an ongoing approach in order of the Ministry of Health and Medical Education in Iran with the aim of reducing cesarean deliveries and making the best decision possible for the mother and neonate.

Developing guidelines to provide quality services was another suggestion in this study. Some efforts have been made in this field by the Maternity Health Office of the Ministry of Health and Medical Education and guidelines were introduced as a reference for students of midwifery and residents of obstetrics. However, participants believe this is not enough and well defined, and specifies guideline are needed for better decision-making in conducting deliveries by obstetricians and midwives, this would also reduce the concerns of midwives and obstetricians.

Caesarean revenues and profitability for hospitals is without doubt an important issue associated with a greater tendency for hospitals to have a cesarean delivery instead of vaginal birth. It was proposed in this study that insurance companies should have more supervision in preventing unnecessary cesarean deliveries and also allocating more tariffs to vaginal birth than cesarean deliveries. Other studies have shown a relationship between cesarean delivery rates and insurance handling.[30] Pregnant women who have health insurance have increased rates of elective caesarean section; in these cases, insurance companies can act by increased monitoring and controlling measures to prevent cesarean deliveries. If tariffs of vaginal delivery be allocated to “service” instead of “agent” of delivery, either hospital can benefit or delivery agent will be a real person that should sign the documents.

Many participants suggested that the accreditation of the hospital must be subject to induce managers control cesarean deliveries rates. Indeed if a delivery room does have the standard criteria for vaginal delivery and has a high cesarean delivery rate, then that hospital should not be accredited, which is true only for emergency room. In other words, if an emergency room does not earn the minimum required standards, the hospital will be excluded from the accreditation process.

Obviously women are also an important part of the complex process of choosing delivery mode,[31] and in many cases the main reason for elective caesarean section, is the mother uninformed request.[21] Thus, a variety of ways can be used to enable them to make informed decisions.

Mothers’ concerns about labor pain as reported in many studies,[9,11] were strongly emphasized by the participants in this study. They said that due to increased rates of cesarean delivery in the country, many midwives and obstetricians have lost their professional competency, or they lack of standard physical spaces, have manpower shortages for care in labor, making it impossible to provide pain relief care for mothers. Therefore, introducing pain relief issues in the curriculums of midwifery education and obstetricians were suggested as an effective way to reduce the inclination of the mothers to cesarean deliveries. In addition, educating mothers on pain and labor physiology for increasing their knowledge and help them to overcome fear of labor.[32]

Moreover, pleasant memories from the previous delivery in the mother or her family members decrease fear from labor; on the contrary, unpleasant memories from the previous labor lead mothers to choose cesarean deliveries.[33] The atmosphere in which the privacy of the mother is respected and where Doula may be present to support the mother, offers comfort and induces pleasant memory to the mother.

A lot of people, including women and health care providers, know cesarean delivery as a very safe and comfortable mode of child birth, and unfortunately they are not aware of its complications. Hence, it is very important to encourage mothers to vaginal birth. This may be achieved by closer interaction between health policy makers and mass media policy makers to influence women to choose vaginal delivery. The role of childbirth preparation classes was reported in another study.[34]

Another supposed strategy in this study was performance supervision and to provide feedback to health care providers to control cesarean delivery rates, as other studies showed its efficacy.[35]

Creating an integrated information management database for evaluating obstetrician's performance in regard to cesarean section rates was another strategy. Obstetrician should be acknowledged if his or her performance lowered cesarean delivery rates and increased vaginal deliveries c. It is clear that different indices should be defined for tertiary referral centers.

The present study was the first research in mixed methodology that strategies come up in a qualitative study from key informants and then examined quantitatively across the country. The authors tried to obtain opinions of specialists in diverse expertise to reach a comprehensive review. So the authors think that strategies that emerged from the study are indigenous and feasible. A limitation of this study is that mothers’ experiences and perspectives were not considered. But in extensive literature review we attained their viewpoints accordance with the results of this study.

CONCLUSIONS

In the present situation with current encouraging population policies in the country, this is a concern, as cesarean section rates among low-risk women continue to rise so controlling cesarean surgery rates is critical. Our results can be used by policy makers and health service managers. Several strategies explored in this study by key informants qualitatively and examined and prioritized quantitatively to reduce cesarean section rates.

Overall, the strategies could work that consider the leading role of qualified midwives in conducting normal vaginal deliveries, and skilled obstetricians in management of complicated deliveries, informing the community about the outcomes of caesarean section to able mothers to make a proper decision for their delivery and finally, promote standards and developing regulation and legislation to provide good quality care.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge the individuals who willingly participated and shared their golden time and valuable experience in order to make this study possible so far. We would also like to acknowledge Ms. Nilufar Shiva for language editing of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Source of Support: This project has been funded by WHO

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Population Policy Advice by Ayatollah Khamenei. [Last accessed on 2014 May 20]. Available from: http://www.leader.ir/langs/fa/index.php?p=contentShow and id=11847 .

- 2.Belizán JM, Althabe F, Cafferata ML. Health consequences of the increasing caesarean section rates. Epidemiology. 2007;18:485–6. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e318068646a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahmad-Nia S, Delavar B, Eini-Zinab H, Kazemipour S, Mehryar AH, Naghavi M. Caesarean section in the Islamic Republic of Iran: Prevalence and some sociodemographic correlates. East Mediterr Health J. 2009;15:1389–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tehran: Ministry of Health and Medical Education. The Fertility Assessment Program. Family Health Section; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Villar J, Valladares E, Wojdyla D, Zavaleta N, Carroli G, Velazco A, et al. Caesarean delivery rates and pregnancy outcomes: The 2005 WHO global survey on maternal and perinatal health in Latin America. Lancet. 2006;367:1819–29. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68704-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lumbiganon P, Laopaiboon M, Gülmezoglu AM, Souza JP, Taneepanichskul S, Ruyan P, et al. Method of delivery and pregnancy outcomes in Asia: The WHO global survey on maternal and perinatal health 2007-08. Lancet. 2010;375:490–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61870-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chaillet N, Dumont A. Evidence-based strategies for reducing cesarean section rates: A meta-analysis. Birth. 2007;34:53–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536X.2006.00146.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moini A, Riazi K, Ebrahimi A, Ostovan N. Caesarean section rates in teaching hospitals of Tehran: 1999-2003. East Mediterr Health J. 2007;13:457–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yazdizadeh B, Nedjat S, Mohammad K, Rashidian A, Changizi N, Majdzadeh R. Cesarean section rate in Iran, multidimensional approaches for behavioral change of providers: A qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:159. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-11-159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hemminki E, Klemetti R, Gissler M. Cesarean section rates among health professionals in Finland, 1990-2006. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2009;88:1138–44. doi: 10.1080/00016340903214957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Størksen HT, Garthus-Niegel S, Vangen S, Eberhard-Gran M. The impact of previous birth experiences on maternal fear of childbirth. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2013;92:318–24. doi: 10.1111/aogs.12072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu NH, Mazzoni A, Zamberlin N, Colomar M, Chang OH, Arnaud L, et al. Preferences for mode of delivery in nulliparous Argentinean women: A qualitative study. Reprod Health. 2013;10:2. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-10-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jamshidmanesh M, Oskouie SF, Jouybary L, AS. The process of women's decision making for selection of cesarean delivery. Iran J Nurs. 2009;21:55–67. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nwobodo EI, Isah AY, Panti A. Elective caesarean section in a tertiary hospital in Sokoto, north western Nigeria. Niger Med J. 2011;52:263–5. doi: 10.4103/0300-1652.93801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ministry of Health and Medical Education, Deputy for Health; Family Health Office, Maternity Health Office. National Matenity Health Program in Forth Development Program (2005-2009) [Last accessed on 2014 Mar 17]. Available from: http://www.arums.ac.ir/opencms/export/sites/default/fa/ard-behdasht/download/salamate_madarane_4.pdf .

- 16.Hartmann KE, Andrews JC, Jerome RN. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2012. [Last accessed on 2014 Mar 27]. Strategies to Reduce Cesarean Birth in Low-Risk Women; p. 80. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK114747 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Badakhsh MH, Seifoddin M, Khodakarami N, Gholami R, Moghimi S. Rise in cesarean section rate over a 30-year period in a public hospital in Tehran, Iran. Arch Iran Med. 2012;15:4–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Creswell JW, Plano Clark VL. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2007. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lincoln Y, Guba E. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publication; 1985. Naturalistic Inquiry. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Strauss A, Corbin J. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1998. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abdullah L, Adawiyah CW. Simple additive weighting methods of multi criteria decision making and applications: A decade review. Int J Inf Process Manag. 2014;5:38–49. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Polit D, Beck CT. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkin Co; 2006. Essential of Nursing Research: Method, Appraisal and Utilization. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Villar J, Carroli G, Zavaleta N, Donner A, Wojdyla D, Faundes A, et al. Maternal and neonatal individual risks and benefits associated with caesarean delivery: Multicentre prospective study. BMJ. 2007;335:1025. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39363.706956.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hyde MJ, Modi N. The long-term effects of birth by caesarean section: The case for a randomised controlled trial. Early Hum Dev. 2012;88:943–9. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Caughey AB, Cahill AG, Guise JM, Rouse DJ American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (College), Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Safe prevention of the primary cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210:179–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion No 394, December 2007. Cesarean delivery on maternal request. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:1501. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000291577.01569.4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang SY, Sheu SJ, Tai CJ, Chiang CP, Chien LY. Decision-making process for choosing an elective cesarean delivery among primiparas in Taiwan. Matern Child Health J. 2013;17:842–51. doi: 10.1007/s10995-012-1062-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Poma PA. Effect of departmental policies on cesarean delivery rates: A community hospital experience. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;91:1013–8. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(98)00077-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Althabe F, Belizán JM. Caesarean section: The paradox. Lancet. 2006;368:1472–3. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69616-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lei H, Wen SW, Walker M. Determinants of caesarean delivery among women hospitalized for childbirth in a remote population in China. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2003;25:937–43. doi: 10.1016/s1701-2163(16)30242-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu JM, Viswanathan M, Ivy JS North Carolina Research Collaborative on Mode of Delivery (NCRC-MOD) A conceptual framework for future research on mode of delivery. Matern Child Health J. 2012;16:1447–54. doi: 10.1007/s10995-011-0910-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McLachlan HL, Forster DA, Davey MA, Farrell T, Gold L, Biro MA, et al. Effects of continuity of care by a primary midwife (caseload midwifery) on caesarean section rates in women of low obstetric risk: The COSMOS randomised controlled trial. BJOG. 2012;119:1483–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2012.03446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pawelec M, Pietras J, Karmowski A, Palczynski B, Karmowski M, Nowak T. Fear-driven cesarean section on request. Pol Merkur Lekarski. 2012;33:86–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tully KP, Ball HL. Misrecognition of need: Women's experiences of and explanations for undergoing cesarean delivery. Soc Sci Med. 2013;85:103–11. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.02.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Main EK. Reducing cesarean birth rates with data-driven quality improvement activities. Pediatrics. 1999;103:374–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]