Abstract

Background

Refugees and asylum seekers often struggle to use general practice services in resettlement countries.

Aim

To describe and analyse the literature on the experiences of refugees and asylum seekers using general practice services in countries of resettlement.

Design and setting

Literature review using systematic search and narrative data extraction and synthesis methodologies. International, peer-reviewed literature published in English language between 1990 and 2013.

Method

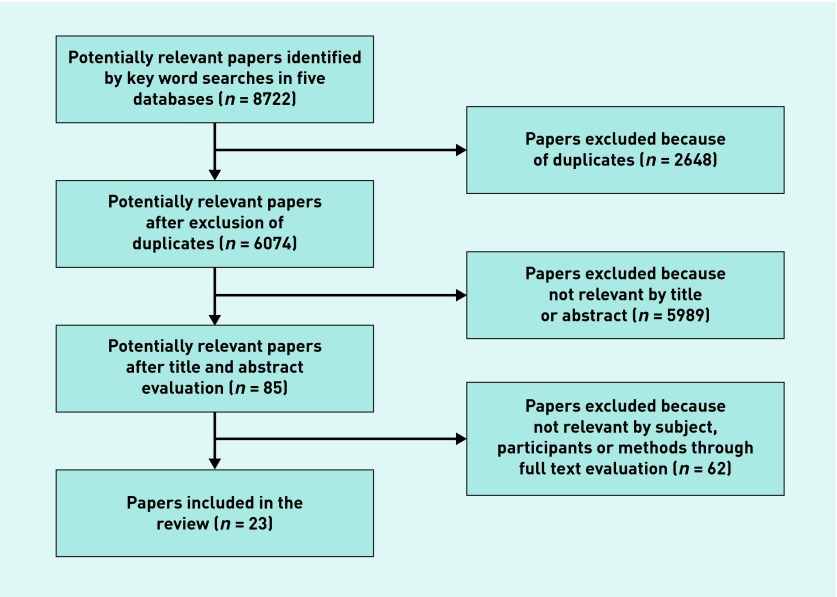

Embase, Ovid MEDLINE, PsycINFO, CSA Sociological Abstracts, and CINAHL databases were searched using the terms: refugee, asylum seeker, experience, perception, doctor, physician, and general practitioner. Titles, abstracts and full texts were reviewed and were critically appraised. Narrative themes describing the refugee or asylum seeker’s personal experiences of general practice services were identified, coded, and analysed.

Results

From 8722 papers, 85 were fully reviewed and 23 included. These represented the experiences of approximately 864 individuals using general practice services across 11 countries. Common narrative themes that emerged were: difficulties accessing general practice services, language barriers, poor doctor–patient relationships, and problems with the cultural acceptability of medical care.

Conclusion

The difficulties refugees and asylum seekers experience accessing and using general practice services could be addressed by providing practical support for patients to register, make appointments, and attend services, and through using interpreters. Clinicians should look beyond refugee stereotypes to focus on the needs and expectations of the individual. They should provide clear explanations about unfamiliar clinical processes and treatments while offering timely management.

Keywords: general practice, health services accessibility, patient acceptance of health care, patient-centred care, physician patient relations, refugees

INTRODUCTION

With the assistance of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), 88 600 refugees were permanently resettled across 22 developed countries including the US, Canada, the UK, Sweden, Norway, Australia, and New Zealand in 2012. In the same year, an additional 893 700 people submitted claims for asylum, requesting protection in these and other countries.1

During resettlement, the main burden of addressing refugee and asylum seeker health needs falls to primary care providers such as GPs and family physicians.2–4 Although primary care services are delivered differently in each country, they generally offer ‘entry into the health system for all new needs and problems, person-focused care over time, care for most conditions, and the coordination and integration of health care provided by others’.5

Nevertheless, refugees and asylum seekers can struggle to access primary care services and services can struggle to provide them with appropriate care. Being ‘outside their country of nationality’ can contribute to difficulties related to language and cultural differences, limited health system literacy, and socioeconomic disadvantage; ‘a fear of being persecuted’ can contribute to complex mental health issues.2–4,6–8 Furthermore, the restricted healthcare rights of asylum seekers in different countries can limit service access.9,10

For primary care to be more responsive to the distinctive needs of refugees and asylum seekers, a better understanding is required of the specific difficulties they experience with services.11 While perceptions of care are also influenced by personal expectations, listening primarily to narratives of experiences provides a stronger grounding in health services reality.12 Although there have been studies describing individual experiences at health services, at the time of this study there were no peer-reviewed literature reviews available on this subject.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to describe and analyse what is known in the international, published literature about the experiences of refugees and asylum seekers concerning GP services in resettlement countries. This is to inform primary care service providers, planners, policy makers, and researchers.

METHOD

Study design

An international, peer-reviewed literature review was conducted using systematic literature search methodology13 and narrative data extraction and analysis techniques.14 Design was informed by descriptive metasynthesis methodology ‘to collate and analyse existing data … [to provide] a more comprehensive and integrated description of the phenomenon not apparent from individual studies alone’.15

How this fits in

Although it is known that refugees and asylum seekers struggle to access and use general practice services in resettlement countries, there is limited published literature from the refugee perspective on the reasons why. This literature review collates, analyses, and synthesises what has been published in 23 papers concerning the experiences of 864 refugees and asylum seekers in 11 countries, to inform the delivery of general practice to this vulnerable population.

Two investigators conducted the searches, extractions, and analysis with assistants. Discordant results were resolved by consensus.

Search strategy

The search strategy used five electronic databases covering primary health care and human experience literature: Ovid MEDLINE®, Embase, CINAHL, PsycINFO, and CSA Sociological Abstracts. The search terms were a combination of refugee* or asylum seek*, and one of: doctor* or physician* or general practi*or experience* or perception*.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

English language literature published between 1990 and 2013 was reviewed. Included was literature that collected primary data describing the individual refugee or asylum seeker’s personal experiences of GP services in countries of permanent resettlement as defined by the UNHCR.1 Excluded was literature that presented experiences of mixed populations broader than refugees and asylum seekers, literature that combined experiences of health services beyond general practice, and literature that collated perceptions of refugee or asylum seeker experiences from secondary agents. Critical appraisal of qualitative literature was conducted using the Letts et al Critical Review Form: Qualitative Studies (version 2.0).16

Data extraction and analysis

The full text of each paper was loaded into NVivo 9 software. Narrative themes of experience were identified de novo from each paper and coded by the investigators. Individual themes were clustered into key themes, which were then re-checked across all papers and synthesised to produce coherent findings.

RESULTS

From 8772 potentially relevant papers, 23 papers were included in the review (Figure 1). The studies were conducted in the US,17–23 Canada,24 England,25–27 Scotland,28,29 Ireland,30 Netherlands,31,32 Norway,33 Sweden,34 Finland,35 Switzerland,36 New Zealand,37,38 and Australia.39

Figure 1.

Literature identification and selection

Thirteen papers focused on refugees, three on asylum seekers, and seven combined both. Because of limitations in distinguishing clearly between the population groups in the data, the results are presented here as a combined group, hereafter known as ‘refugees’.

The studies represented the experiences of approximately 864 individuals from 43 countries. Most studies combined multiple ethnic groups, while four studies focused exclusively on people from Somalia,17,19,21,38 and one each focused only on people from Bosnia, Ethiopia, Iran, Afghanistan, and Sri Lanka.22,24,27,31,33

All selected studies used qualitative methods and collected data through interviews with individuals, families, or focus groups. Many used a grounded theory approach to analysis. No quantitative studies met the full inclusion criteria.

Four recurring narrative themes emerged from the literature: difficulty accessing services, language barriers, poor doctor–patient relationships, and problems with the cultural acceptability of medical care.

Access to services

Refugees described significant difficulties accessing GPs throughout the analysed literature. They struggled with a lack of knowledge about the health system26 and described systems as complicated and difficult to understand.21 Knowledge gaps included the role of the GP,27 where to find a GP,25 how to make an appointment,19 and how to access out-of-hours primary care:28,29

‘I hadn’t even heard the word GP before you know!’ 28

Refugees found it difficult to register at practices and to make appointments because of limited knowledge of processes and language barriers.22,25,28 Registration and appointment making were facilitated with assistance from friends, family, support workers, and the NHS Health Board in the UK:25,27,28

‘If I don’t have anybody to make the appointment for me I can’t do it [myself].’ 19

Refugees described difficulties with transport to and from services.17,19,20,38 They struggled with the costs of medical care,17–22,39 especially medicines:21,28,29

‘I just find it very hard when I am sick, I can’t afford to pay for a doctor.’ 39

Sometimes access was limited by visa entitlements or insurance programmes.22,25 They also expressed frustration with waiting days to years for an appointment22,28,29,39 and with long waiting times in clinics.18,19,27

Language barriers

In relation to access, language barriers were commonly experienced. These included differences in spoken language, understanding written materials, completing paperwork, and problems with the use of interpreters:18–21,25,38,39

‘I don’t feel satisfied when I can’t understand my doctor.’ 21

Although services at times provided professional interpreters,17,25,28,37 there was confusion about who was responsible for providing an interpreter.20,30 Problems occurred when interpreters were not available or when their use was denied:18–20,25,27,28,30,31

‘If there is no (trained) interpreter and you cannot explain the problem how can you clarify the problem, how can you get quality care from the GP?’ 30

Family members and friends were also used as interpreters.17,18,20,25,30 The use of children was felt to be appropriate by some but inappropriate by others, especially when discussing personal matters.25,30

Refugees were concerned that interpreters were not re-telling their stories or explaining medical concepts adequately,20,26,28 resulting in misdiagnosis or inappropriate treatment.30 They expressed fears about personal information being passed on to others in the community:25–26,28,30

‘… maybe he [the interpreter] doesn’t say exactly what you feel. For example he might say that I feel mad when I feel depressed. It’s not good for confidentiality as they talk too much in the community.’ 26

Interpreter gender concordance facilitated communication;19 however, some females did not seem troubled by its absence.25

Doctor–patient relationships

Refugees expressed concerns about doctors who did not seem interested in them,19,31,36 ask about their past experiences,23 listen to them well,18,21,25,29,31 or seem to understand them.18,29,31,36 They preferred doctors who were friendly, welcoming, open, sympathetic, and kind.19,29,31,32,36 They appreciated doctors who made them feel valued and respected as a whole person,19,21,29,33,36 and who were sensitive to gender, cultural beliefs, and practices:18,19,21

‘They are nice … but doctors/nurses don’t listen and understand us.’ 18

Some felt unfairly stereotyped as a refugee or discriminated against as a migrant.18,21,28,29,31 Some were afraid to go to a doctor because they felt unwanted or a burden on resources:25

‘Sometimes I feel they’ll be fed up with me, especially a foreigner …’ 25

Refugees appreciated doctors who spent extended amounts of time with them in history taking, physical examination, and explanation.19,21,31,32,39 Continuity with the same doctor was helpful in building mutual familiarity and trust;19,25,28,29 they expressed dissatisfaction at being given a different doctor or interpreter at each visit:25,28,34

‘I used to go to [a former health centre] but I didn’t like that. Cause I didn’t see the doctor. They made me see different doctors. I didn’t like it that way.’ 19

Cultural acceptability of medical care

Refugee perceptions of medical assessments and treatments were shaped by pre-existing health beliefs and expectations of health care.21 Problems occurred when there was dissonance between their expectations and their actual experiences of care:

‘We came here with hope to get better right away, so when we seek treatment and we don’t get [better], we feel frustrated. We came here with [the] hope that all these problems we have [will] go away. So we [become] disappointed.’ 20

Some refugees were confused when they did not understand why they were being physically examined in a particular way,19,21,28 or not at all:19,20,29,31

‘I was seen by four different doctors in the surgery … and none of them actually touched me to see what was wrong, to examine my throat; where it is sore.’ 28

Some did not understand the nature of screening or diagnostic tests,21,28 or felt frustrated when results did not provide definitive answers to concerns:36

‘I don’t know what I have. They did tests, they don’t know what I have.’ 36

The provision of health education and advice was problematic when refugees did not understand,29 or when treatment expectations were not met:21,29,31

‘They [healthcare providers] don’t give me anything ... They tell me, drink water, eat food, take NyQuil™ [cold-symptom relief]... They are supposed to provide me with something ...’ 21

Psychological support from the GP in the form of encouraging the expression of emotions and counselling helped to acknowledge suffering and provided ways of relieving distress.26,36 Nevertheless, there was a perception that GPs sometimes offered unjustified psychological explanations for physical complaints:31

‘GPs think that we … always have psychological problems. That is not true. Of course we have suffered a lot of misery, but this is another story. A gallstone has nothing to do with a psychological problem.’ 32

Prescription medicines were welcomed by many refugees,19,21 although some were disappointed when they were not prescribed antibiotics, particularly when antibiotics were readily available in their country of origin.28 Sometimes prescriptions were seen as a replacement for serious professional attention:29,31,32

‘They gave me just antibiotics and didn’t take time.’ 29

Referrals to other health services were valued; however, limitations in the types of services referred to and delays in being referred to specialist doctors caused frustration:22,24,26,28,31

‘ [In Bosnia] if the primary care physician is giving you a referral for a specialist, you can go the same day to see the other doctor, the specialist. Then if you need to come back from the specialist to the primary care doctor you can do that ... This is one of the biggest problems here, that you don’t have access.’ 22

DISCUSSION

Summary

In this review, four common and interrelated themes emerged concerning refugee experiences of general practice care: difficulties accessing services, language barriers, poor doctor–patient relationships, and problems with the cultural acceptability of medical care.

Refugees experienced a wide range of difficulties accessing GP services related to limited knowledge of how to access services, difficulties registering and making appointments, inadequate transport, and unaffordable service costs. Although provision of practical support and fee subsidies was beneficial, multiple strategies are required to address access difficulties.

Spoken and written language barriers were commonly experienced and had a significant impact across many aspects of care. Although refugees used professional interpreters, family, and friends to assist with communication, there were problems with their availability and concerns about accuracy and confidentiality. Gender concordance, trusting relationships, and using the same person to interpret at each visit were beneficial but did not fully negate the primary concerns.

The relationship with the doctor was problematic when the refugee did not feel valued or respected as an individual person. They preferred to see doctors who were friendly and welcoming; those who showed an interest in, listened to, and understood them; those who spent adequate time with them and with whom they developed trust. Stereotyping as a refugee, discrimination as a migrant, and cultural insensitivity were particular concerns of this population that needed to be addressed in the relationship.

The nature of clinical assessments and treatments were not well understood or accepted when pre-existing beliefs about health and expectations of health care were not met. Refugees preferred clinical assessment methods to be consistent with cultural expectations and explanations of unfamiliar processes and treatments. They welcomed education and lifestyle advice but not at the exclusion of prescription medicines or timely access to specialist doctors.

Of the three papers that focused exclusively on asylum seekers, the common themes included a lack of available interpreter services, inadequate cultural competency, and difficulties with the cost of medical care.18,35,39 These themes were very similar to those expressed by the broader population of refugees. Further research studies focusing on the distinctive needs of asylum seekers may be helpful in understanding their unique experiences of care.

Strengths and limitations

The included papers used qualitative methods to describe a breadth of refugee experiences and were in sufficient quantity to identify and illuminate recurrent narrative themes. Although there was a wide range of participants from various ethnic groups in multiple resettlement countries, the limited number of papers did not allow for conclusions concerning the experiences of specific ethnic groups or country contexts.

Comparison with existing literature

The literature showed similarities with studies concerning refugee experiences of broader health services, particularly relating to language barriers and difficulties accessing health care.40

Compared with non-refugee populations, refugees shared a common desire for GPs to be competent, informative, and humane.31,41 They experienced similar problems to other migrant groups in accessing health services, language and cultural differences, and doctor–patient relationships.19,42 Distinctive refugee experiences related to stereotyping and identity where refugees felt they were overdiagnosed with psychological conditions or felt they were an unwanted burden on health services on account of being a refugee.25,31,32

Implications for research and practice

Future research should include publishing more studies of refugee experiences of GP services in each of the settlement countries. Focusing on specific ethnic groups would assist to elucidate cultural differences. A ‘grey’ literature review of this subject would complement existing findings.

Mindful that each country has different healthcare systems and policies relating to refugees and asylum seekers, support should be given to refugees to better understand how to access GP services, and to be able to register, make appointments, and attend services. Support should be given to GP clinics to provide professional interpreters to patients when needed.

GPs should take care to look beyond refugee stereotypes, value the individual, and focus on his or her needs. They should provide clear explanations of unfamiliar clinical assessment processes and treatments while providing timely management that is mindful of patient expectations.

These findings have broader implications for medical education, professional standards, health system policies, and wider research to support the delivery of quality GP services to refugees and asylum seekers.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Leon Piterman, Chris Anderson, Anna Chapman, Samantha Thomas, Grant Russell, Joanne Enticott, Surabhi Kumble, Jessica Dumble, and the staff of the Monash University Hargrave-Andrew Library and the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners John Murtagh Library. The Southern Academic Primary Care Research Unit is an organisational partnership of Monash University, South Eastern Melbourne Medicare Local and Monash Health.

Funding

This project has been supported with funding from the Australian Government Department of Health under the Primary Health Care Research Evaluation and Development (PHCRED) Initiative.

Ethical approval

Not required.

Provenance

Freely submitted; externally peer reviewed.

Competing interests

The authors have declared no competing interests.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article: bjgp.org/letters

REFERENCES

- 1.United National High Commissioner for Refugees . UNHCR Global Trends 2012. Geneva: UNHCR; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hargreaves S, Holmes A, Friedland JS. Refugees, asylum seekers, and general practice: room for improvement? Br J Gen Pract. 2000;50(456):531–532. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones D, Gill PS. Refugees and primary care: Tackling the inequalities. Br Med J. 1998;317(7170):1444–1446. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7170.1444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eckstein B. Primary care for refugees. Am Fam Physician. 2011;83(4):429–436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Starfield B. Primary care: balancing health needs, services and technology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harris M, Zwar N. Refugee health. Aust Fam Physician. 2005;34(10):825–829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taylor K. Asylum seekers, refugees, and the politics of access to health care: A UK perspective. Br J Gen Pract. 2009;59(567):765–772. doi: 10.3399/bjgp09X472539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.United National High Commissioner for Refugees . Convention and protocol relating to the status of refugees. Geneva: UNHCR; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reeves M, de Wildt G, Murshali H, et al. Access to health care for people seeking asylum in the UK. Br J Gen Pract. 2006;56(525):306–308. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spike EA, Smith MM, Harris MF. Access to primary health care services by community-based asylum seekers. Med J Aust. 2011;195(4):188–191. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2011.tb03277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raven M. Patient experience of primary health care. Adelaide: Primary Health Care Research and Information Service; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sofaer S, Firminger K. Patient perceptions of the quality of health services. Annu Rev Public Health. 2005;26:513–559. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.25.050503.153958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Version 5.1.0. 2011. Mar, The Cochrane Collaboration, updated http://www.cochrane-handbook.org (accessed 18 Dec 2014) [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jupp V, editor. The SAGE dictionary of social research methods. London: SAGE Publications; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Finfgeld D. Metasynthesis: the state of the art so far. Qual Health Res. 2003;13(7):893–904. doi: 10.1177/1049732303253462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Letts L, Wilkins S, Law M. Guidelines for critical review form: qualitative studies (version 2.0) Hamilton: McMaster University; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adair R, Nwaneri MO, Barnes N. Health care access for Somali refugees: views of patients, doctors, nurses. Am J Health Behav. 1999;23(4):286–292. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Asgary R, Segar N. Barriers to health care access among refugee asylum seekers. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2011;22(2):506–522. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2011.0047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carroll J, Epstein R, Fiscella K, et al. Caring for Somali women: implications for clinician-patient communication. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;66(3):337–345. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morris MD, Popper ST, Rodwell TC, et al. Healthcare barriers of refugees post-resettlement. J Community Health. 2009;34(6):529–538. doi: 10.1007/s10900-009-9175-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pavlish CL, Noor S, Brandt J. Somali immigrant women and the American health care system: discordant beliefs, divergent expectations, and silent worries. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(2):353–361. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Searight HR. Bosnian immigrants’ perceptions of the United States health care system: a qualitative interview study. J Immigr Health. 2003;5(2):87–93. doi: 10.1023/a:1022907909721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shannon P, O’Dougherty M, Mehta E. Refugees’ perspectives on barriers to communication about trauma histories in primary care. Ment Health Fam Med. 2012;9(1):47–55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dastjerdi M, Olson K, Ogilvie L. A study of Iranian immigrants’ experiences of accessing Canadian health care services: a grounded theory. Int J Equity Health. 2012;11(1):55. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-11-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bhatia R, Wallace P. Experiences of refugees and asylum seekers in general practice: a qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract. 2007;8:48. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-8-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Palmer D, Ward K. ‘Lost’: listening to the voices and mental health needs of forced migrants in London. Med Confl Surviv. 2007;23(3):198–212. doi: 10.1080/13623690701417345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Papadopoulos I, Lees S, Lay M, Gebrehiwot A. Ethiopian Refugees in the UK: migration, adaptation and settlement experiences and their relevance to health. Ethnic Health. 2004;9(1):55–73. doi: 10.1080/1355785042000202745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O’Donnell CA, Higgins M, Chauhan R, Mullen K. They think we’re OK and we know we’re not. A qualitative study of asylum seekers’ access, knowledge and views to health care in the UK. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7:75. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-7-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O’Donnell CA, Higgins M, Chauhan R, Mullen K. Asylum seekers’ expectations of and trust in general practice: a qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract. 2008;58(557):870–876. doi: 10.3399/bjgp08X376104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.MacFarlane A, Dzebisova Z, Karapish D, et al. Arranging and negotiating the use of informal interpreters in general practice consultations: experiences of refugees and asylum seekers in the west of Ireland. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(2):210–214. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Feldmann CT, Bensing JM, De Ruijter A, Boeije HR. Afghan refugees and their general practitioners in the Netherlands: to trust or not to trust? Sociol Health Illn. 2007;29(4):515–535. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2007.01005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Feldmann CT, Bensing JM, de Ruijter A. Worries are the mother of many diseases: general practitioners and refugees in the Netherlands on stress, being ill and prejudice. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;65(3):369–380. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gronseth AS. In search of community: a quest for well-being among Tamil refugees in northern Norway. Med Anthropol Q. 2001;15(4):493–514. doi: 10.1525/maq.2001.15.4.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Razavi MF, Falk L, Bjorn A, Wilhelmsson S. Experiences of the Swedish healthcare system: an interview study with refugees in need of long-term health care. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(3):319–325. doi: 10.1177/1403494811399655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koehn PH, Sainola-Rodriguez K. Clinician/patient connections in ethnoculturally nonconcordant encounters with political-asylum seekers: a comparison of physicians and nurses. J Transcult Nurs. 2005;16(4):298–311. doi: 10.1177/1043659605278936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Perron NJ, Hudelson P. Somatisation: Illness perspectives of asylum seeker and refugee patients from the former country of Yugoslavia. BMC Fam Pract. 2006;7:10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-7-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blakely T. Health needs of Cambodian and Vietnamese refugees in Porirua. N Z Med J. 1996;109(1031):381–384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guerin B, Abdi A, Geurin P. Experiences with the medical and health systems for Somali refugees living in Hamilton. N Z J Psychol. 2003;32(1):27–32. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Spike EA, Smith MM, Harris MF. Access to primary health care services by community-based asylum seekers. Med J Aust. 2011;195(4):188–191. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2011.tb03277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lipson JG, Weinstein HM, Gladstone EA, Sarnoff RH. Bosnian and Soviet refugees’ experiences with health care. West J Nurs Res. 2003;25(7):854–871. doi: 10.1177/0193945903256714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scheppers E, van Dongen E, Dekker J, et al. Potential barriers to the use of health services among ethnic minorities: a review. Fam Pract. 2006;23(3):325–348. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmi113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wensing M, Jung HP, Mainz J, et al. A systematic review of the literature on patient priorities for general practice care. Part 1: Description of the research domain. Soc Sci Med. 1998;47(10):1573–1588. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00222-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]