Abstract

Surface modification of titanium dioxide (TiO2) nanoparticle is essential to control its surface properties, thereby to enhance its cell penetration capability, reduce its cytotoxicity, or improve its biocompatibility. In order to graft polyvinyl acetate onto TiO2 nanoparticles, xanthate was chemically immobilized on the surface of TiO2 by acylation followed by nucleophilic substitution with a carbodithioate salt. Reversible addition fragmentation chain transfer polymerization was conducted to graft vinyl acetate onto the surface of TiO2. Both the TiO2-xanthate and TiO2-polyvinyl acetate hybrids were characterized by UV-Vis spectroscopy, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy, and thermogravimetric analysis. The chemical immobilization of xanthate on the surface of TiO2 and the subsequent controlled polymerization provide useful insight for decoration and modification of TiO2 and other nanoparticles.

Keywords: Surface grafting, xanthate, RAFT polymerization, titanium dioxide

Introduction

Titanium dioxide (TiO2) is being extensively studied due to its highly valuable applications in the field of solar cell, photodegradation, and biotechnology such as sunscreens in skin care product, tissue engineering, and biosensors (1–4). As one of the most investigated metal oxides with a band gap of 3.0~3.2 eV, the surface properties of TiO2 have been highly addressed in order to more precisely understand the potential mechanism and improve the efficiencies in different circumstances (3,4). In order to apply TiO2 in health science, the surface properties should be rendered via surface modification to decrease its cytotoxicity, reduce its DNA damage, and enhance its biocompatibility (5). Surface modification of TiO2 can be executed by a number of methods, such as doping by nanoparticles of metals, deposition by metal, coating with silane coupling agents, and/or decoration by polymers and other adsorbates (4).

In the last two decades, controlled polymerization such as atomic transfer-radical polymerization (ATRP) or reversible addition fragmentation chain transfer (RAFT) has been systematically investigated. Both techniques have provided powerful strategies to explore numerous materials and/or devices with significantly improved performance (6–10). As two representative controlled radical polymerization technologies, ATRP and RAFT polymerizations are fully capable of designing new materials with controlled and complex structures (6,11–12). Among those, surface initiated polymerization provides a unique strategy to graft polymer on the surface of inorganic particles. To do so, physical or chemical immobilization of the corresponding initiator or transfer agent on the surface of inorganic particle has been extensively investigated as an efficient method for organic-inorganic hybrids and composites (11, 14). Although both techniques are able to effectively graft polymer on the surface of nanoparticles in a controlled manner, halides (e.g. bromide) and copper ion (Cu+) are normally the essential components for ATRP initiation and polymerization, which greatly impede the wide applications, especially in specific circumstance with biocompatibility (15). Herein, a chemical modification of TiO2 was employed to introduce a typical RAFT agent, xanthate (C2H5-O-C(=S)-S-R), on the surface of TiO2 nanoparticles, in which the activating group (Z) of the xanthate RAFT agent was O-alkyl (16, 17). A subsequent surface initiated RAFT polymerization of vinyl acetate was demonstrated and the grafting effectiveness was evaluated by UV-Vis and Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectrascopy as well as thermogrametric analysis (TGA).

Materials and Methods

Materials

Potassium ethyl xanthogenate (96%), vinyl acetate (VAc, ≥99%), 2,2′-azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN, 98%) and α-bromoisobutyryl bromide (98%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (MO, USA). VAc was purified by passing through silica column and AIBN was recrystallized in ethanol before use. Triethylamine (99%, Acros, Belgium) and titanium dioxide (TiO2, Aeroxide®, P25, Acros, Belgium) were used as received.

Preparation of TiO2-xanthate

Because xanthate is one representative RAFT agent which can well control the polymerization of vinyl monomers (15–17), xanthate was chosen to immobilize onto TiO2 to graft vinyl acetate through the surface initiated polymerization. Typically, immobilization of xanthate onto TiO2 was performed as below. Ten g of pristine TiO2 was dispersed in 200 mL of 1,4-dioxane. After addition of 3.3 g of triethylamine (Et3N), 7.4 g of α-bromoisobutyryl bromide was slowly added into the flask. After 24 h’s reaction at room temperature, the slurry was precipitated by centrifuge and washed at least 3 times with acetone/water (5/1, v/v). The obtained TiO2-Br was further dispersed into 200 mL of 1,4-dioxane and 5.0 g of potassium ethyl xanthate was added into the suspension. After the reaction was performed at room temperature for 24 h, the suspension was purified by centrifuge and washed at least 3 times with acetone/water (5/1, v/v). The obtained TiO2-xanthate was dried in a vacuum oven at 40 °C for overnight.

Surface initiated RAFT polymerization

The RAFT polymerization was performed in 1,4-dioxane under Argon atmosphere. Briefly, 0.5 g of TiO2-xanthate was first dispersed in 10 mL of 1,4-dioxane at vigorous stirring. One gram of vinyl acetate and 0.3 mg of AIBN were then loaded into the suspension. Since a high molar ratio of RAFT/initiator is desirable for well controlled polymerization (19,20), a relatively high ratio of 5/1 (RAFT/AIBN) was chosen to prevent the conventional radical polymerization. The RAFT agent immobilized on TiO2 surface was estimated by TGA. After polymerization for 24 h at 70 °C, the suspension was centrifuged and washed by hexane (3 × 50 mL) to completely remove the ungrafted polyvinyl acetate. The obtained TiO2-polyvinyl acetate hybrid was finally dried in a vacuum oven at 40 °C prior to characterization by FTIR spectroscopy and TGA. The preparation of TiO2-xanthate and the corresponding surface initiated polymerization were illustrated in Scheme 1.

Scheme 1.

Scheme for immobilization of xanthate onto TiO2 particle and the surface initiated RAFT polymerization

Characterizations

UV-Vis spectroscopy was completed using a Cary 5000 UV-Vis-NIR spectrometer (Agilent Tech, CA, USA). Ethanol was used as the solvent. TGA was performed on a Q 500 thermogravimetric analyzer (TA Instruments, DE, USA) in air atmosphere with a heating rate of 20 °C/min. FTIR spectroscopy was performed on a Nicolet 6700 FTIR Spectrometer by using a Smart Orbit accessory. Each spectrum was collected after 32 scans at a resolution of 2 cm−1.

Results and Discussion

Because xanthate is one of the representative chain transfer agents for RAFT polymerization of vinyl acetate, xanthate was chosen to immobilize onto TiO2 to graft vinyl acetate through the surface initiated polymerization (16–18). Due to lack of reactivity of the surface hydroxyl groups on TiO2 particles, the immobilization was performed via a two-step reaction, in which α-bromoisobutyryl bromide was first immobilized onto TiO2 particles through an esterification reaction. Potassium ethyl xanthogenate was then linked through a nucleophilic substituion to the bromoisobutyryl. The synthetic route of TiO2-xanthate is shown in Scheme 1.

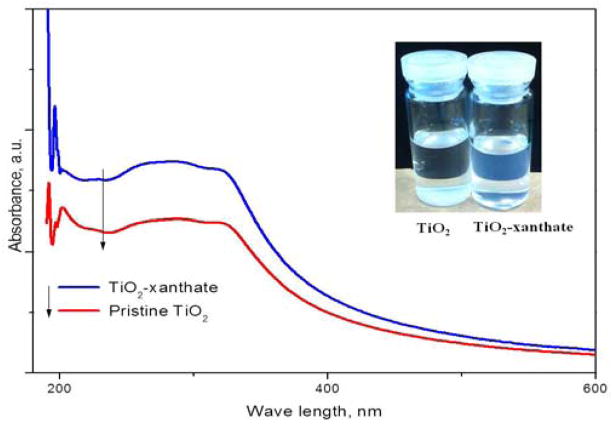

The chemical immobilization of xanthate agent on surface of TiO2 significantly influenced the surface properties of TiO2 and its dispersibility and stability. The UV-Vis spectroscopy of pristine TiO2 and decorated TiO2 are shown in Fig. 1. The absorbance of TiO2-xanthate exhibited a greater absorbance than that of pristine TiO2 when the concentration of TiO2 was kept the same. This indicated that the organic coating could lead to a more homogeneous dispersion of TiO2-xanthate. In addition, the xanthate could alter the dispersion capability and stability of TiO2 in ethanol solvent. The stability of the ethanol suspension was evaluated by the precipitation test. The pristine TiO2 without any treatment precipitated within 1 h, but TiO2-xanthate still dispersed in ethanol even after 1 day at room temperature.

Figure 1.

UV-Vis spectroscopy of TiO2 and TiO2-xanthate in ethanol; insert is the corresponding dispersion after 1 day at room temperature.

The FTIR spectra of TiO2, TiO2-xanthate and TiO2-polyvinyl acetate confirmed the polymer grafting effectiveness (Fig. 2). The FTIR spectra of TiO2 and TiO2-xanthate were very similar, implying that the xanthate RAFT agent immobilized on the surface of TiO2 was too little to be observed. However, when the surface initiated RAFT polymerization was performed, the characteristic peaks of polyvinyl acetate could be clearly detected. The peaks at 2925 and 2849 cm−1 were assigned to the methylene groups, while the peaks at 2960 and 2890 cm−1 could be assigned to methyl groups (21,22).

Figure 2.

FTIR spectra of TiO2, TiO2-xanthate and TiO2-polyvinyl acetate.

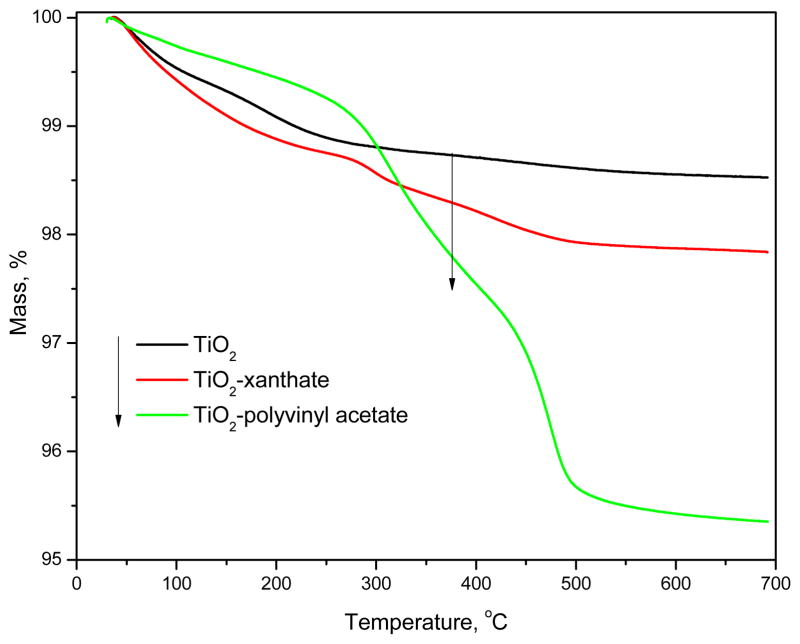

TGA provides further information about the chemically modified particles such as the quantitative fraction of polymer and thermal stability of the hybrids. The TGA curves of pristine TiO2, TiO2-xanthate and TiO2-polyvinyl acetate are shown in Fig. 3. TGA curves of pristine TiO2 and TiO2-xanthate had the similar profiles with the greatest weight difference (0.8%) at 700 °C. This could be attributed to the amount of xanthate (relative to TiO2) which has been grafted onto the surface of TiO2. In comparison, the TGA curve of TiO2-polyvinyl acetate had significant mass loss. By comparing the mass loss between pristine TiO2 and TiO2-polyvinyl acetate, we could infer that about 3.2% polymer (relative to TiO2) had been successfully grafted onto TiO2 nanoparticles.

Figure 3.

TGA curves of pristine TiO2, TiO2-xanthate and TiO2-polyvinyl acetate

Conclusions

A chemical immobilization of xanthate on TiO2 was executed by acylation and further nucleophilic substitution with a carbodithioate salt. The polyvinyl acetate was then covalently connected onto the surface of TiO2 via the surface initiated RAFT polymerization. Both the FTIR and TGA evidence indicated that around 3.2 wt% polyvinyl acetate was immobilized on the surface of TiO2.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by National Institutes of Health of the USA (NIH/NIDCR/R01DE021786).

References

- 1.Diebold U. The surface science of titanium dioxide. Surf Sci Rep. 2003;48:53–229. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang P, Zakeeruddin SM, Exnar I, Gratzel M. High efficiency dye-sensitized nanocrystalline solar cells based on ionic liquid polymer gel electrolyte. Chem Commun. 2002:2972–3. doi: 10.1039/b209322g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hagfeldt A, Boschloo G, Sun L, Kloo L, Pettersson H. Dye-sensitized solar cells. Chem Rev. 2010;110:6595–663. doi: 10.1021/cr900356p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park H, Park Y, Kim W, Choi W. Surface modification of TiO2 photocatalyst for environmental applications. J Photochem Photobiol C-Photochem Rev. 2013;15:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mano SS, Kanehira K, Sonezaki S, Taniguchi A. Effect of Polyethylene Glycol Modification of TiO2 Nanoparticles on Cytotoxicity and Gene Expressions in Human Cell Lines. Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13:3703–3717. doi: 10.3390/ijms13033703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boyer C, Stenzel MH, Davis TP. Building nanostructures using RAFT polymerization. J Polym Sci A Polym Chem. 2011;49:551–95. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moad G, Rizzardo E, Thang SH. Living Radical Polymerization by the RAFT Process. Aust J Chem. 2005;58:379–410. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zetterlund PB, Kagawa Y, Okubo M. Controlled/living radical polymerization in dispersed systems. Chem Rev. 2008;108:3747–94. doi: 10.1021/cr800242x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qiu J, Charleux B, Matyjaszewski K. Controlled/living radical polymerization in aqueous media: homogeneous and heterogeneous systems. Prog Polym Sci. 2001;26:2083–134. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gao H, Matyjaszewski K. Synthesis of functional polymers with controlled architecture by CRP of monomers in the presence of cross-linkers: From stars to gels. Prog Polym Sci. 2009;34:317–50. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beija M, Marty J-D, Destarac M. RAFT/MADIX polymers for the preparation of polymer/inorganic nanohybrids. Prog Polym Sci. 2011;36:845–86. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu D, Xu F, Sun B, Fu R, He H, Matyjaszewski K. Design and Preparation of Porous Polymers. Chem Rev. 2012;112:3959–4015. doi: 10.1021/cr200440z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Braunecker WA, Matyjaszewski K. Controlled/living radical polymerization: Features, developments, and perspectives. Prog Polym Sci. 2007;32:93–146. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gregory A, Stenzel MH. Complex polymer architectures via RAFT polymerization: From fundamental process to extending the scope using click chemistry and nature’s building blocks. Prog Polym Sci. 2012;37:38–105. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boyer C, Bulmus V, Davis TP, Ladmiral V, Liu J, Perrier S. Bioapplications of RAFT polymerization. Chem Rev. 2009;109:5402–36. doi: 10.1021/cr9001403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mori H, Yanagi M, Endo T. RAFT polymerization of N-vinylimidazolium salts and synthesis of thermoresponsive ionic liquid block copolymers. Macromolecules. 2009;42:8082–92. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keddie DJ, Moad G, Rizzardo E, Thang SH. RAFT Agent Design and Synthesis. Macromolecules. 2012;45:5321–42. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stenzel MH, Davis TP, Barner-Kowollik C. Poly(vinyl alcohol) star polymers prepared via MADIX/RAFT polymerisation. Chem Commun. 2004;10:1546–7. doi: 10.1039/b404763j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chiefari J, Chong YK, Ercole F, Krstina J, Jeffery J, Le TPT, Mayadunne RTA, Meijs GF, Moad CL, Moad G, Rizzardo E, Thang SH. Living free-radical polymerization by reversible addition-fragmentation chain transfer: The RAFT process. Macromolecules. 1998;31:5559–62. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chiefari J, Mayadunne RTA, Moad CL, Moad G, Rizzardo E, Postma A, Skidmore MA, Thang SH. Thiocarbonylthio compounds (S=C(Z)S-R) in free radical polymerization with reversible addition-fragmentation chain transfer (RAFT polymerization). Effect of the activating group. Z Macromolecules. 2003;36:2273–83. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nguyen V, Yoshida W, Cohen Y. Graft polymerization of vinyl acetate onto silica. J Appl Polym Sci. 2003;87:300–10. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sabzi M, Mirabedini SM, Zohuriaan-Mehr J, Atai M. Surface modification of TiO2 nano-particles with silane coupling agent and investigation of its effect on the properties of polyurethane composite coating. Prog Org Coat. 2009;65:222–8. [Google Scholar]