Abstract

Common bile duct exploration (CBDE) is an accepted treatment for choledocholithiasis. This procedure is not well studied in the elderly population. Here we evaluate the results of CBDE in elderly patients (>70 years) and compare the open (group A) with the laparoscopic group (group B). A retrospective review was performed of elderly patients with proven common bile duct (CBD) stones who underwent CBDE from January 2005 to December 2009. There were 55 patients in group A and 33 patients in group B. Mean age was 77.6 years (70–91 years). Both groups had similar demographics, liver function tests, and stone size—12 mm (range, 5–28 mm). Patients who had empyema (n = 9), acute cholecystitis (n = 15), and those who had had emergency surgery (n = 28) were more likely to be in group A (P < 0.05). The mean length of stay for group A was 11.7 ± 7.3 days; for group B, 5.2 ± 6.3 days; the complication rate was higher in group A (group A, 38.2%; group B, 8.5%; P = 0.072). The overall complication and mortality rate was 29.5% and 3.4%, respectively. CBDE can be performed safely in the elderly with accepted morbidity and mortality. The laparoscopic approach is feasible and safe in elective setting even in the elderly.

Key words: Common bile duct exploration, Elderly, Laparoscopy

The treatment of common bile duct (CDB) stones varies, and the optimal management is still a matter of debate.1 The treatment options include pre- or postoperative endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) with laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) or common bile duct exploration (CBDE) with LC or open cholecystectomy (OC). LC is necessary, as up to 47% of patients will develop recurrent symptoms from cholelithiasis.2 However, in the former approach (ERCP with LC), patients will have to undergo 2 procedures and be exposed to the risks of ERCP. ERCP has a mortality and morbidity rate of up to 1% and 15.9%, respectively.3,4 Furthermore, patients who opt for preoperative ERCP may still require CBDE if stone clearance is not achieved and may eventually end up having multiple procedures.5–7

Although laparoscopic common bile duct exploration (LCBDE) is an accepted treatment, the technical difficulties associated with this procedure have made it slower to gain widespread acceptance.8 Nonetheless, as surgeons gain more expertise and experience in laparoscopic biliary surgery, LCBDE is fast becoming part of the armamentarium for dealing with CBD stones. The safety and efficacy of LCBDE is well studied in the general population. In the literature, the ductal stone clearance rate for all comers is approximately 85% to 97.3% and has an associated mortality rate of 0.3% to 0.8% and morbidity of 3.7% to 33%.9–13 The overall length of stay is shorter in LCBDE compared with the 2-stage approach.14 With all these advantages, it has even been suggested that LCBDE is the preferred treatment, especially in patients who are fit and young.15 Of interest, the incidence of CBD stones is higher in the elderly; however, this procedure is not well studied in this group of patients.16,17 There are also concerns regarding the safety of biliary tract surgery in elderly patients especially in the acute setting.18 With this in mind, this retrospective study aimed to evaluate and analyze the results of CBDE in elderly patients and to compare the results between the open and laparoscopic groups.

Methods

Patients

A retrospective review of all elderly patients (>70 years), who underwent CBDE in the Department of Surgery at the National University of Singapore affiliated academic institute between January 2005 and December 2009, was performed. Data collected included patient demographics, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) status, comorbidity, presenting diagnosis, laboratory and radiologic investigations, operative details, length of stay, and complications. A total of 88 CBDE were performed during this study period. In our hospital, ERCP was performed both by hepatobiliary surgeons and gastroenterologists. Patients who presented acutely with biliary obstruction and ongoing sepsis would initially undergo decompression with either an ERCP or percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC) if ERCP was unsuccessful. Following successful biliary decompression and resolution of sepsis, these patients would undergo subsequent surgery. The surgery offered would include either LC or OC. CBDE would also be performed in those who did not have stone clearance in the acute setting or those who were found to have CBD stones intraoperatively. Some patients would undergo surgery in the acute setting if they were not improving despite decompression and antibiotics or if there was suspicion for empyema. For patients who could not tolerate prolonged surgery or were suspected to have empyema preoperatively, open surgery would be offered. The preoperative diagnosis of CBD stones was made using a combination of ultrasonography (US), computerized tomography (CT) scan, and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP).

Definition

Cholecystitis and cholangitis were diagnosed according to Tokyo guidelines criteria.19,20 Acute pancreatitis was diagnosed by the Atlanta classification.21 Empyema was suspected if there was persistent sepsis despite intravenous antibiotics or was diagnosed intraoperatively with the finding of pus in the gallbladder.

Techniques

LCBDE

Four ports were utilized as for standard LC using an American approach. Patients would receive a single dose of antibiotic prophylaxis. A transcystic intraoperative cholangiography (IOC) was routinely performed to document the presence of CBD stones before proceeding to explore the common bile duct via either a transcystic or a transcholedochal approach. The transcholedochal approach was reserved for failed transcystic exploration.

Transcystic approach

The transcystic route is the default method of exploration. It is performed with a basket either under fluoroscopy or by direct visualization. Under fluoroscopic guidance, a 5.5-Fr Nathanson basket kit (Cook, Queensland, Australia) was used and pushed distally toward the duodenum to retrieve the stones. This process was repeated until all the stones were removed. For the direct visualization approach, a 2.8-mm choledochoscope was used to locate the CBD stones. The Zero Tip Nitinol Stone Retrieval Basket (Boston Scientific Microvasive, Natick, Massachusetts) was then placed through the working port and used to retrieve the stones. Once the basket had captured the stones, both the choledochoscope and the basket were removed in tandem.

Transcholedochal approach

For the transcholedochal route, a longitudinal choledochotomy was made in the supraduodenal CBD after adequate exposure; next, a 5-mm choledochoscope was inserted and a basket was used to retrieve the stones. After choledochotomy, it was the surgeon's preference to either perform primary closure or some form of biliary drainage. Primary closure was performed with interrupted sutures using 3/0 polyglactin. Biliary drainage is achieved by placement of either a T-tube or an endobiliary stent.

Open CBDE

After adequate exposure with Kocher's incision, Calot's triangle was dissected to expose the cystic duct and common bile duct. This was followed by cholecystectomy. A vertical choledochotomy was then made between stay sutures. A 5-mm choledochoscope and Dormia basket (Boston Scientific, Boston, MA) is used to retrieve stones under vision.

Documentation of stone clearance after bile duct exploration may be achieved with either a completion cholangiogram or a check choledochoscopy. The placement of an abdominal drain is left to the surgeon's discretion.

Postoperative care

If a T-tube was placed, a cholangiogram was usually performed on the 5th to 7th postoperative day. After a normal study, the tube would be removed 4 to 6 weeks later. A C stent would also be removed 4 to 6 weeks later at the endoscopy suite.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed with Stata v10.2 (Stata Corp, College Station, Texas). The level of significance was set at 5%. The χ2 test as well as Student independent t test was used to compare characteristics between the 2 groups. The binary logistic-regression model was used to study the independent association between the various factors and the 2 groups.

Results

During the study period, 130 CBDEs were performed. Eighty-eight CBDEs were performed in the elderly with a mean age of 77.6 years (range, 70–91 years). Patients who underwent open and laparoscopic CBDE were designated group A and group B, respectively. There were 55 patients in group A. Group B included 33 patients with 6 patients converted to open surgery. These 6 patients were excluded from analysis.

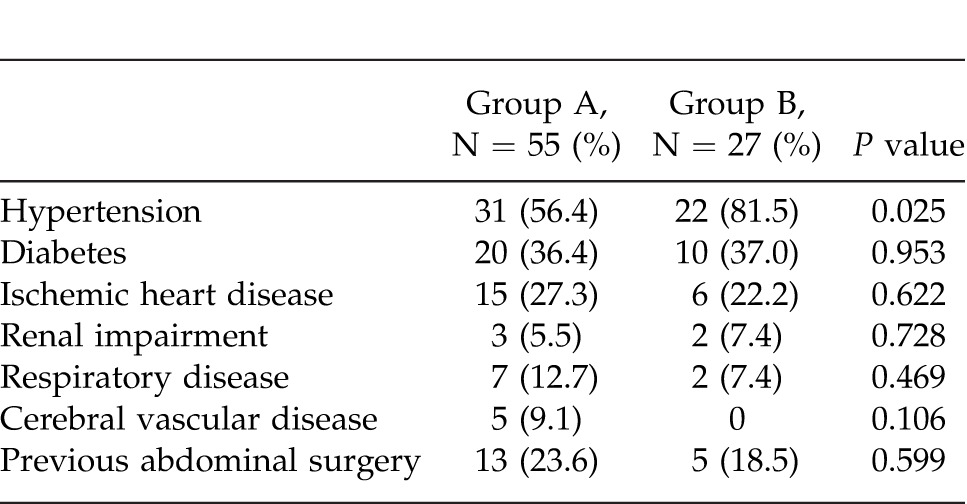

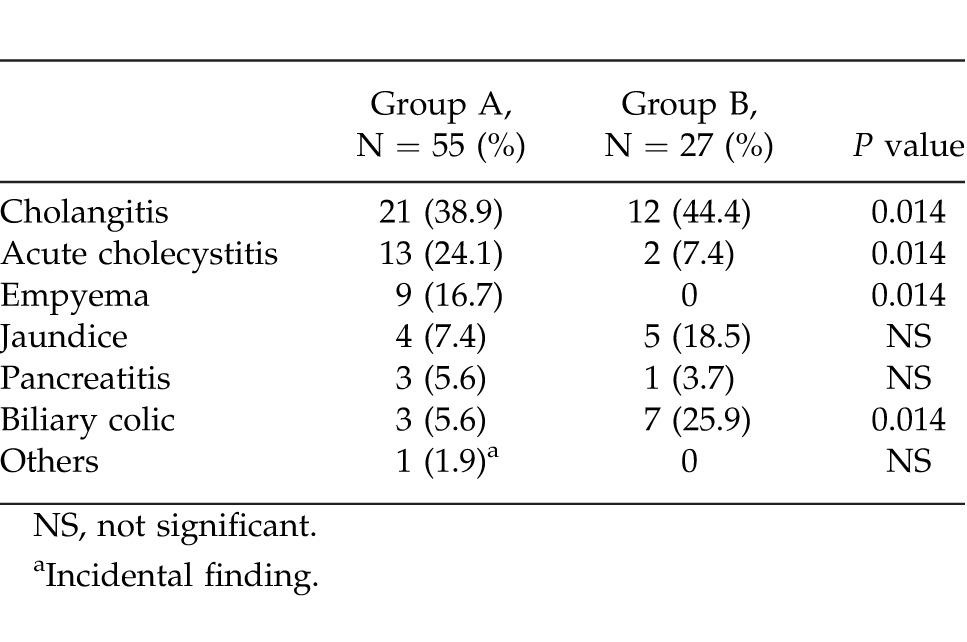

There was similar age and sex distribution among both groups A and B. With regard to patient comorbidity, there were no statistically significant differences between the 2 groups except for hypertension, which was more common in group B (81.5% versus 56.4%; P = 0.025) (Table 1). The diagnosis at the time of admission is shown in Table 2. Group A had significantly more empyema (16.7% versus 0%; P = 0.014) and acute cholecystitis (24.1% versus 7.4%; P = 0.014). Group B had more biliary colic (25.9% versus 5.6%; P = 0.014). In this study, 35.4% of the patients underwent emergency surgery. Most of these patients were in group A compared with group B (92.0% versus 8.0%; P = 0.001). There were more patients with ASA III (68.5% versus 40.7%; P = 0.03) and less patients with ASA II (29.6% versus 59.3%; P = 0.03) in group A compared with group B.

Table 1.

Patient comorbidity

Table 2.

Diagnosis at time of admission

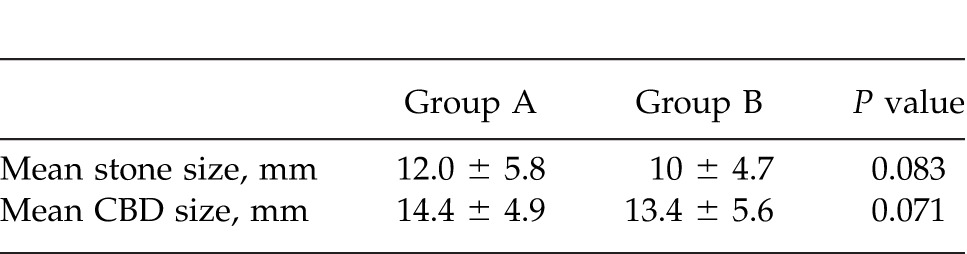

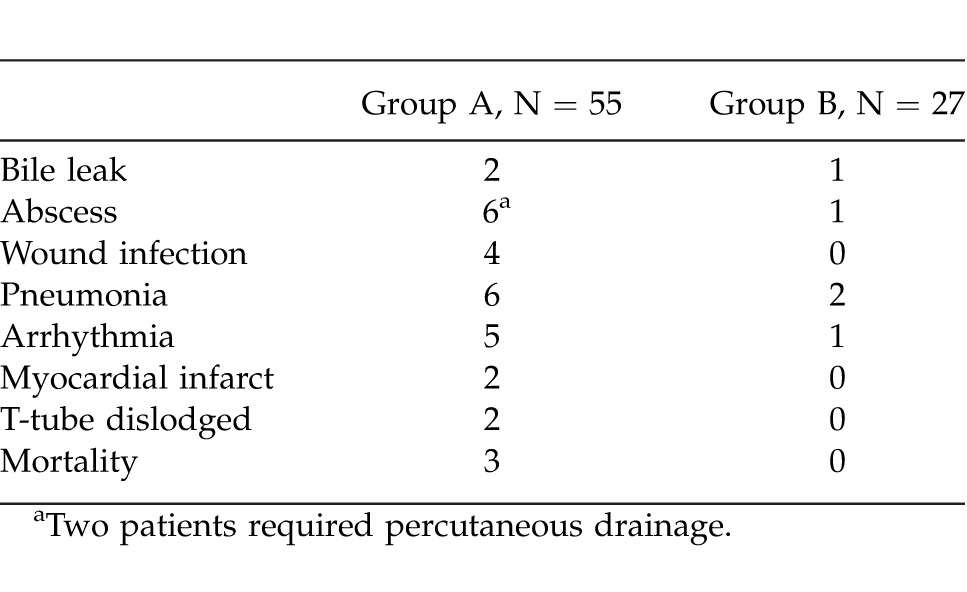

The liver function tests were comparable in both groups. CBD size and mean stone size were also comparable (Table 3). The duration of surgery did not differ between the groups (160 ± 63.8 minutes versus 193.3 ± 84.0 minutes; P = 0.972). The mean length of stay was longer in group A compared with group B (11.7 ± 7.3 days versus 5.2 ± 6.3 days; P = 0.003). There were a total of 33 complications in 26 patients with an overall complication rate of 29.5%.There were 3 mortalities (3.4%) in this study, and they were all in group A. Group A also had a significantly higher complication rate (38.2% versus 18.5%; P = 0.072).

Table 3.

Stone and CBD size

The complications are listed in Table 4. The patients with pneumonia and wound infection were treated with intravenous antibiotics and subsequently discharged home with antibiotics. There were 7 patients with intraabdominal abscesses of which 2 patients required percutaneous drainage. These 2 patients required intervention as they were showing fever, leucocytosis, and abdominal tenderness despite intravenous antibiotics. The abscesses were diagnosed with either US or CT scan when patients had fever, leucocytosis, or abdominal signs. Two patients had their T-tube dislodged: one patient developed postoperative confusion and pulled out the T-tube, while the other had her T-tube dislodged accidentally during transport. In these 2 patients, CT scans were performed. They were treated conservatively with antibiotics as the scans did not demonstrate any collection. They were monitored for 3 to 5 days in the hospital before being discharged. There were a total of 5 patients with retained stones (5.7%), and they were all in group A. These retained stones were picked up on postoperative T-tube cholangiogram. On repeat T-tube cholangiogram performed 6 weeks later, 2 patients had spontaneous passage of stones. One patient underwent further ERCP, and the other patient had percutaneous intervention. The last patient underwent open surgery, as he was found to have gallbladder carcinoma on histology. There were 5 patients who were very septic after emergency surgery and required inotropic support in the surgical intensive care unit. Of these 5 patients, 3 developed multiorgan failure and eventually passed away. These 3 patients belonged to group A.

Table 4.

Complications and mortality

Discussion

Common bile duct stones occur in up to 15% of patients.22 Both surgical and endoscopic approaches are established modalities of treatment with comparable stone clearance rates.6 One-stage procedure eliminates the need for ERCP and its associated risks. Another advantage of CBDE is the avoidance of postoperative ERCP in patients with unsuspected CBD stones discovered intraoperatively. Furthermore, if postoperative ERCP is unsuccessful, patients may have to undergo a second operation with an additional anesthetic risk. Since LC became the standard of care for symptomatic cholelithiasis, open cholecystectomy has been restricted to either malignant gallbladder disease or conversion after a laparoscopic attempt. Laparoscopic biliary surgery is not as widely prevalent. Open CBDE is necessary in certain situations such as those that require a concomitant biliary enteric drainage and those that failed or could not tolerate LCBDE or ERCP.

One difficult group of patients is the elderly, with multiple medical comorbidities. Unfortunately, the incidence of CBD stones is found to be higher in this population.16 Earlier studies of biliary tract surgery in elderly patients, especially in the acute setting, raised some concerns regarding the safety profile and complication rates.23,24 With advances in surgical techniques and critical care medicine, mortality of biliary surgery is acceptable. Although endoscopic extraction or stent placements without LC are an option, the significant recurrence rates and subsequent complications should restrict this approach to select elderly patients with prohibitive surgical risk and limited life expectancy.25,26 Moreover, stents have their own associated complications and need to be changed at intervals. We restrict such an approach to a highly select group of patients who are not fit for anesthesia.

LCBDE is a highly effective and safe procedure, but this expertise is not available in all centers.11–13,27 Furthermore, the safety profile of this procedure is not well studied in the elderly. To our knowledge, apart from this article, there is only one other study in the English literature looking specifically at LCBDE in the elderly.28 In our study, there were 55 patients in the open group and 27 patients in the LCBDE group. All patients were over 70 years of age, and most were in ASA class II or III. The most common presenting diagnosis was cholangitis and acute cholecystitis. Both groups had comparable demographics and medical comorbidity except for hypertension, which was more common in group B (81.5% versus 56.4%; P = 0.025). This is because these patients were not randomized. The operating time in the LCBDE group was higher but did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.79). This is probably owing to the technical difficulties associated with surgery in relatively more sick patients. The complication rate of the open CBDE was higher (38.2%) as compared with the LCBDE group (18.5%). This is because patients in the open group tend to be more ill as reflected by a significantly higher incidence of ASA III patients (68.5% versus 40.7%; P = 0.03) in the open group. There were also more cases of empyema (16.7% versus 0%; P = 0.014) and acute cholecystitis (24.1% versus 7.4%; P = 0.014) in the open group. With regard to the complications, about half of them were medical in nature. This would be expected as these were elderly patients with multiple comorbidities. The rest of the complications, such as bile leaks, intra-abdominal abscess, and wound infection, were surgically related. However, of all the patients with the above complications, only 2 required intervention for them. Furthermore, the T-tubes that were dislodged in 2 patients were not the result of poor surgical technique.

The mean length of stay in the LCBDE was shorter compared with the open group (5.2 ± 6.3 days versus 11.7 ± 7.3 days; P = 0.003). A recent randomized trial showed that LCBDE when compared with ERCP with LC resulted in lower physician fees.14 Although a cost analysis was not performed in this study, these 2 advantages can potentially lead to reduced overall cost. The length of stay in the open CBDE group was higher owing to significant comorbidity that required preoperative optimization as well as postoperative monitoring. In this study, we did not compare the techniques used in the LCBDE. However, it is generally accepted that both techniques are equally effective. The transcystic route is usually used for patients who have fewer stones and smaller CBD stones.29,30 Choledochotomy is more commonly performed for multiple and large stones.31 We routinely make an attempt at transcystic exploration unless the stone size is adjudged to be too big to be retrieved, typically >10 mm. Choledochotomy is usually accompanied by some form of biliary decompression with either a T-tube or an endobiliary stent. There is no consensus on which is better, but a T-tube offers some advantages.32 It provides an access for cholangiography, and removal of occasional retained stones. However, the use of a T-tube has its own complications. Biliary sepsis, bile duct trauma, bile leakage, retention of a fragment, and stricture formation after T-tube removal have been reported. The use of C stent is usually associated with a shorter length of stay.33 But these patients will need an additional procedure and are exposed to the risk of endoscopy during stent removal. In our experience, there were no complications related to endobiliary stents; however, 2 patients had T-tube dislodgement. T-tube dislodgement is a sinister clinical problem with a potential for biliary peritonitis and the need for reoperation.

In our study, we had 6 conversions. The reasons for conversion include 3 patients with dense adhesions, 1 patient who required a bypass owing to multiple stones, 1 patient who had a suspected common hepatic duct injury, and 1 patient who had an abnormal anatomy, which made LCBDE technically difficult to perform. Open conversion in the patient with the suspected hepatic duct injury revealed a through and through perforation of cystic duct with the basket, and there was no common hepatic ductal injury evident. The case note review of the patient with abnormal anatomy did not provide a detailed description. The incidence of retained stones was 5.7% in this study. This is comparable to other studies in the literature.31,34 The management options of retained stones include a variety of methods such as flushing, chemical dissolution through the T-tube, ERCP with or without stent placement, and reoperation. If nonoperative management fails, and reoperation is contemplated, additional drainage procedures such as a sphincteroplasty or choledochoduodenostomy should be considered in patients with risk factors that predispose them to further stone disease.35,36 Our overall mortality rate was only 3.4% and the complication rate was 29.5%. The 3 mortalities in our study belonged to the open group. These results are superior to some studies in the literature,24 where poorer outcomes were noted in elderly patients when operated on in the emergency setting.18,23 This difference in results may be because more than half of our patients (n = 51) were operated on after allowing the acute episode to settle. It is important to provide physiologic restorative support prior to embarking on a surgery. In severe cholangitis, urgent biliary decompression is a mandatory adjunct to a physiologic restoration, and common bile duct exploration is contraindicated. In our study, there was no mortality in the LCBDE group. The other study on LCBDE in the elderly has a reported mortality rate of only 1.3%.28 This further supports our view that LCBDE can be safely performed in the elderly.

Conclusions

Our results have shown that CBDE by open or laparoscopic techniques can be performed safely in the elderly with accepted morbidity and mortality. Laparoscopic CBDE can be done safely in elderly patients in the elective setting.

References

- 1.Targarona EM. Even Bendahan G. Management of common bile duct stones: controversies and future perspectives. HPB (Oxford) 2004;6(3):140–143. doi: 10.1080/13651820410025156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boerma D, Rauws EA, Keulemans YC, Janssen IM, Bolwerk CJ, Timmer R, et al. Wait-and-see policy or laparoscopic cholecystectomy after endoscopic sphincterotomy for bile-duct stones: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;360(9335):761–765. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09896-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Christensen M, Matzen P, Schulze S, Rosenberg J. Complications of ERCP: a prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60(5):721–731. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)02169-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fielding GA. The case for laparoscopic common bile duct exploration. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2002;9(6):723–728. doi: 10.1007/s005340200099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neoptolemos JP, Carr-Locke DL, Fossard DP. Prospective randomised study of preoperative endoscopic sphincterotomy versus surgery alone for common bile duct stones. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1987;294(6570):470–474. doi: 10.1136/bmj.294.6570.470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martin DJ, Vernon DR, Toouli J. Surgical versus endoscopic treatment of bile duct stones. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;XX(2):CD003327. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003327.pub2. Available at: https://www.med.upenn.edu/gastro/documents/CochranereviewCBDstones.pdf. Accessed April 21, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fletcher DR. Changes in the practice of biliary surgery and ERCP during the introduction of laparoscopic cholecystectomy to Australia: their possible significance. Aust N Z J Surg. 1994;64(2):75–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1994.tb02147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keeling NJ, Menzies D, Motson RW. Laparoscopic exploration of the common bile duct: beyond the learning curve. Surg Endosc. 1999;13(2):109–112. doi: 10.1007/s004649900916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bove A, Bongarzoni G, Palone G, Di Renzo RM, Calisesi EM, Corradetti L, et al. Why is there recurrence after transcystic laparoscopic bile duct clearance? Risk factor analysis. Surg Endosc. 2009;23(7):1470–1475. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0377-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tinoco R, Tinoco A, El-Kadre L, Peres L, Sueth D. Laparoscopic common bile duct exploration. Ann Surg. 2008;247(4):674–679. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181612c85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lezoche E, Paganini AM. Single-stage laparoscopic treatment of gallstones and common bile duct stones in 120 unselected, consecutive patients. Surg Endosc. 1995;9(10):1070–1075. doi: 10.1007/BF00188989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lien HH, Huang CC, Huang CS, Shi MY, Chen DF, Wang NY, et al. Laparoscopic common bile duct exploration with T-tube choledochotomy for the management of choledocholithiasis. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2005;15(3):298–302. doi: 10.1089/lap.2005.15.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tang CN, Tsui KK, Ha JP, Siu WT, Li MK. Laparoscopic exploration of the common bile duct: 10-year experience of 174 patients from a single centre. Hong Kong Med J. 2006;12(3):191–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rogers SJ, Cello JP, Horn JK, Siperstein AE, Schecter WP, Campbell AR, et al. Prospective randomized trial of LC+LCBDE vs ERCP/S+LC for common bile duct stone disease. Arch Surg. 2010;145(1):28–33. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2009.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thompson MH, Tranter SE. All-comers policy for laparoscopic exploration of the common bile duct. Br J Surg. 2002;89(12):1608–1612. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2002.02298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brunt LM, Quasebarth MA, Dunnegan DL, Soper NJ. Outcomes analysis of laparoscopic cholecystectomy in the extremely elderly. Surg Endosc. 2001;15(7):700–705. doi: 10.1007/s004640000388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paganini AM, Feliciotti F, Guerrieri M, Tamburini A, Campagnacci R, Lezoche E. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy and common bile duct exploration are safe for older patients. Surg Endosc. 2002;16(9):1302–1308. doi: 10.1007/s00464-001-8316-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sullivan DM, Hood TR, Griffen WO., Jr Biliary tract surgery in the elderly. Am J Surg. 1982;143(2):218–220. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(82)90072-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kimura Y, Takada T, Kawarada Y, Nimura Y, Hirata K, Sekimoto M, et al. Definitions, pathophysiology, and epidemiology of acute cholangitis and cholecystitis: Tokyo guidelines. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2007;14(1):15–26. doi: 10.1007/s00534-006-1152-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mayumi T, Takada T, Kawarada Y, Nimura Y, Yoshida M, Sekimoto M, et al. Results of the Tokyo Consensus Meeting Tokyo Guidelines. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2007;14(1):114–121. doi: 10.1007/s00534-006-1163-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bollen TL, van Santvoort HC, Besselink MG, van Leeuwen MS, Horvath KD, Freeny PC, et al. The Atlanta Classification of acute pancreatitis revisted. Br J Surg. 2008;95(1):6–21. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hungness ES, Soper NJ. Management of common bile duct stones. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10(4):612–619. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2005.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sandler RS, Maule WF, Baltus ME, Holland KL, Kendall MS. Biliary tract surgery in the elderly. J Gen Intern Med. 1987;2(3):149–154. doi: 10.1007/BF02596141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gonzalez JJ, Sanz L, Grana JL, Bermejo G, Navarrete F, Martinez E. Biliary lithiasis in the elderly patient: morbidity and mortality due to biliary surgery. Hepatogastroenterology. 1997;44(18):1565–1568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Palma GD, Catanzano C. Stenting or surgery for treatment of irretrievable common bile duct calculi in elderly patients? Am J Surg. 1999;178(5):390–393. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(99)00211-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keizman D. Ish Shalom M, Konikoff FM. Recurrent symptomatic common bile duct stones after endoscopic stone extraction in elderly patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64(1):60–65. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bingener J, Schwesinger WH. Management of common bile duct stones in a rural area of the United States: results of a survey. Surg Endosc. 2006;20(4):577–579. doi: 10.1007/s00464-005-0322-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paganini AM, Feliciotti F, Guerrieri M, Tamburini A, Campagnacci R, Lezoche E. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy and common bile duct exploration are safe for older patients. Surg Endosc. 2002;16(9):1302–1308. doi: 10.1007/s00464-001-8316-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lyass S, Phillips EH. Laparoscopic transcystic duct common bile duct exploration. Surg Endosc. 2006;20((suppl 2)):S441–S445. doi: 10.1007/s00464-006-0029-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stromberg C, Nilsson M, Leijonmarck CE. Stone clearance and risk factors for failure in laparoscopic transcystic exploration of the common bile duct. Surg Endosc. 2008;22(5):1194–1199. doi: 10.1007/s00464-007-9448-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dorman JP, Franklin ME, Jr, Glass JL. Laparoscopic common bile duct exploration by choledochotomy: an effective and efficient method of treatment of choledocholithiasis. Surg Endosc. 1998;12(7):926–928. doi: 10.1007/s004649900748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perez G, Escalona A, Jarufe N, Ibanez L, Viviani P, Garcia C, et al. Prospective randomized study of T-tube versus biliary stent for common bile duct decompression after open choledocotomy. World J Surg. 2005;29(7):869–872. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-7698-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shimizu S, Yokohata K, Mizumoto K, Yamaguchi K, Chijiiwa K, Tanaka M. Laparoscopic choledochotomy for bile duct stones. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2002;9(2):201–205. doi: 10.1007/s005340200019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ferzli GS, Massaad A, Kiel T, Worth MH., Jr The utility of laparoscopic common bile duct exploration in the treatment of choledocholithiasis. Surg Endosc. 1994;8(4):296–298. doi: 10.1007/BF00590956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baek YH, Kim HJ, Park JH, Park DI, Cho YK, Sohn CI, et al. Risk factors for recurrent bile duct stones after endoscopic clearance of common bile duct stones [in Korean] Korean J Gastroenterol. 2009;54(1):36–41. doi: 10.4166/kjg.2009.54.1.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cameron JL. Retained and recurrent bile duct stones: operative management. Am J Surg. 1989;158(3):218–221. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(89)90254-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]